Abstract

Background:

Researchers have theorized that increased rates of suicide in the military are associated with combat exposure; however, this hypothesis has received inconsistent support in the literature, potentially because combat exposure may be indirectly related to suicide risk through its influence on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms. The current study tested the hypothesis that combat exposure has a significant indirect effect on suicidal behavior among Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans through its effects on PTSD-depressive symptomatology.

Methods:

Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans (N = 3,238) participated in a cross-sectional, multi-site study of post-deployment mental health consisting of clinical interviews and self-report questionnaires. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine direct and indirect relationships between three latent variables: combat exposure, PTSD-depression, and suicidal behavior (past attempts and current ideation, intent, and preparation).

Results:

A partial mediation model was the best-fitting model for the data. Combat exposure was significantly associated with PTSD-depression (β = .50, p < .001), which was in turn associated with suicidal behavior (β = .62, p < .001). As expected, the indirect effect between combat exposure and suicidal behavior was statistically significant, β = .31, p < .001.

Limitations:

Data were cross-sectional, and suicidal behavior was measured via self-report.

Conclusions:

Results indicated that combat exposure was indirectly related to suicidal behavior via PTSD-depressive symptomatology. Findings lend support for a higher-order combined PTSD-depression latent factor and suggest that Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans with high levels of PTSD-depressive symptoms are at increased risk for suicidal behavior.

Keywords: combat exposure, suicide, PTSD, depression

Introduction

Since the onset of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, rates of suicide in the military have increased significantly (Ramchand, Acosta, Burns, Jaycox, & Pernin, 2011). Researchers have hypothesized that this increase in suicide risk is associated with exposure to combat (Hoge & Castro, 2012; Ramchand et al., 2011). According to the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (IPTS), in order for an individual to engage in suicidal behavior they must have the acquired capability to inflict lethal harm upon themselves (Joiner, 2005). This acquired capability develops through repeated exposure to painful and provocative events such as violence, abuse, and death (Joiner, 2005). As a result, IPTS posits that combat exposure should increase one’s acquired capability for suicide (Selby et al., 2010); however, prior research has not reported consistent relationships between combat exposure and suicidal behavior (Bryan et al., 2016; Bryan, Hernandez, Allison, & Clemans, 2013). For example, a large longitudinal study of current and former military personnel suicides found that combat experience was not associated with heightened risk of suicide (LeardMann et al., 2013)

A recent meta-analysis of 22 published studies among service members and veterans found that combat exposure was associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, but that the effect size was very small, suggesting that there are other factors that contribute to suicide risk (Bryan et al., 2016). The authors of this meta-analysis hypothesized that combat exposure operates as a long-term risk factor for suicide over time but that other acute stressors are more proximally related to suicide-related outcomes. This conceptualization of the relationship between combat exposure and suicide is consistent with the fluid vulnerability theory of suicide (Rudd, 2006), which proposes that suicide risk fluctuates over time as a function of both chronic and acute risk factors. According to this theory, individuals each have a baseline level of suicide risk that is relatively stable over time; however, suicide risk can acutely increase in response to situational triggers.

It is also possible that combat exposure may indirectly influence suicidal behavior by increasing risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptomatology. Prior research has indicated that military service members and veterans with symptoms of PTSD and depression are at heightened risk for suicidal behavior (e.g., Jakupcak et al., 2009; Kimbrel, Calhoun, et al., 2014; Kimbrel, Meyer, DeBeer, Gulliver, & Morissette, 2016; Ramsawh et al., 2014). For example, Kimbrel and colleagues (2016) found that comorbid PTSD and depression were a significant prospective predictor of suicidal behavior at 12-month follow-up. Furthermore, research with civilian samples has also found that comorbid PTSD and depression are more predictive of suicidal behavior than depression alone (e.g., Cougle, Resnick, & Kilpatrick 2009; Oquendo et al., 2005; Oquendo et al., 2003). Thus, combat exposure may have indirect effects on suicidal thoughts and behaviors via PTSD and depressive symptomatology.

In contrast with this theorized indirect effect, Bryan and colleagues (2013) found no evidence for an indirect effect of combat exposure on suicide risk via symptoms of PTSD, depression, and additional variables associated with suicide risk; however, it is quite possible that this was due to the analytical approach employed. For example, this study also included several other variables that were hypothesized to further intervene in between PTSD and depression and suicidality, including thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Thus, the specific indirect effects between combat, PTSD, depression, and suicidality were not examined separately. In addition, PTSD and depression were examined separately and a formal path was not specified between these variables. Instead, the observed variables for PTSD and depression symptoms were co-varied. Notably, in both of the samples that Bryan et al. (2013) examined, significant paths were observed between combat and PTSD. Moreover, a significant covariance was also modeled between PTSD and depression in both samples, and depression was either directly or indirectly related to suicidality in both models. Thus, while combat was not directly related to depression in these models, it was associated with PTSD, which was associated with depression, which was associated with suicidality (either directly or indirectly).

We suspect that if PTSD and depression had been modeled as indicators on a higher-order latent factor that an indirect association between combat and suicidality would have been observed, as there is ample evidence for just such a higher order latent factor (Cox, Clara, & Enns, 2002; Kimbrel, Calhoun, et al., 2014; Miller, Fogler, Wolf, Kaloupek, & Keane, 2008). For example, Miller and colleagues (2008) found that PTSD and depression loaded onto a higher-order “distress” factor among 1,325 Vietnam veterans. Similarly, Kimbrel et al. (2014) found that symptoms of PTSD and depression also loaded onto a higher-order latent “distress” factor among 1,897 Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans, and that a combined PTSD-depression “distress” factor was strongly associated with both current suicidality and history of suicide attempt. Accordingly, the objective of the present study was to use structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypothesis that a combined PTSD-depression latent factor mediates the association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior among a large and diverse sample of Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

A total of 3,238 Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans participated in a cross-sectional, multi-site study of Post-Deployment Mental Health led by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) VISN 6 Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness, Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC). Study procedures have been described in detail elsewhere (Brancu et al., 2017; Kimbrel, Calhoun, et al., 2014). Recruitment began in 2005 and is ongoing. To be eligible for inclusion, participants must have served in the U.S. military after September 11, 2001. Participants were recruited via mailings, advertisements, and referrals. The local institutional review boards at each participating VA site approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. Study procedures consisted of a diagnostic clinical interview and completion of a battery of self-report questionnaires.

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID; First & Pincus, 2002) was used to diagnose current and lifetime PTSD and depression according to DSM-IV-TR criteria. Clinical interviewers received extensive training in SCID administration as well as ongoing supervision from experienced clinicians. Clinical interviewers demonstrated excellent reliability (Fleiss’ kappa = 0.95) when scoring a series of seven training videos.

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS; Beck & Steer, 1991) was used to assess current suicidal behavior and history of suicide attempts. The BSS is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess severity of suicidal ideation, plans, and preparations during the past week. Respondents are asked to rate items on a Likert scale that ranges from 0 to 2, with higher values indicating greater severity. Internal consistency reliability for the BSS was good (α = 0.83). Item 20 from the BSS was used to identify participants with a lifetime history of suicide attempts. The mean BSS score was 0.98 (SD = 3.20; range = 0-32).

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was used to assess the severity of participants’ depressive symptoms during the past two weeks. The scale consists of 21 self-report items that are rated from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity. In the current study, the item assessing suicidal ideation (i.e., item 9) was not included in the total score calculations since the primary outcome variable was suicidal behavior. Instead, this item was used as an additional indicator of suicidal ideation in the suicidal behavior latent variable. Internal consistency for the 20-item version of the BDI-II used in the present study was excellent (α = 0.94). The mean BDI-II score (not including item 9) was 14.30 (SD = 12.57; range = 0-59).

The Combat Exposure Scale (CES; Keane et al., 1989) was used to assess combat exposure. The CES consists of 7-item self-report items that are each rated on a 5-point scale reflecting frequency, duration, or percentage of combat exposure. Internal consistency for the CES was 0.88. The mean CES score was 11.32 (SD = 10.64; range = 0-40).

The Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS; Davidson et al., 1997) was used to assess severity of PTSD symptoms. This is a self-report measure that assesses the 17 symptoms of PTSD, based on the DSM-IV criteria. Participants rate the frequency and severity of each item on a 0 to 4 scale based on how they felt during the past week regarding their most bothersome traumatic event. Internal consistency for the DTS in the present study was excellent (α = 0.98). The mean DTS score was 40.76 (SD = 39.96; range = 0-136).

Data Analysis Plan

Missing data was less than 1% for each of the self-report measures; however, note that clinical interviews were not initially used when the study first began. Consequently, diagnostic data were missing for the first 248 participants who enrolled in the study (7.6%). Mplus 7 was used to conduct the statistical analyses (Muthén & Muthén, 2012), and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to account for missing data and to estimate parameters in the structural equation models (SEM) for the 3,233 participants who had partial data available to analyze. The five participants (0.1%) who had complete missing data were excluded from the analyses.

Three latent variables were created using the study measures. The combat exposure latent variable was created from three item parcels from the CES, as the CES demonstrated poor fit when the individual items were used as indicators (RMSEA = .107) In contrast, the CES exhibited good fit when item parcels were used instead (RMSEA = .00). The indicators for the PTSD-depression latent variable included the sum of the DTS, the sum of the 20-item version of the BDI-II (i.e., minus the suicide item), and the sum of participants’ current and lifetime diagnoses of PTSD and MDD (range is 0-4). The indicators for the suicidal behavior latent variable included BSS total score, BSS item 20, and the BDI-II suicide item.

We initially tested three models that examined the direct effects between combat exposure, PTSD-depressive symptoms, and suicidal behavior, including the following. Model A examined the direct association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior. Model B examined the direct association between combat exposure and PTSD-depressive symptoms. Model C examined the direct association between PTSD-depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior. Next, we examined the fit of the hypothesized full mediation model (Model D) as well as a partial mediation model (Model E) in which a direct path from combat exposure to suicidal behavior was also included in the model. In order to determine whether results differed when suicide-related outcomes were measured differently, we ran two additional versions of the best fitting model. In one additional model, the latent dependent variable was measured using only suicidal ideation items (BSS total score and BDI-II suicide item). In another model, we used an observed dependent variable measuring lifetime suicide attempt (BSS item 20).

Multiple fit indices were used to evaluate the fit of the models, including Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; close fit ≤ .06; adequate fit ≤ .08); Comparative Fit Index (CFI; close fit ≥ .95; adequate fit ≥ .90); Tucker-Lewis Indices (TLI; close fit ≥ .95; adequate fit ≥ .90); Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; close fit ≤ .05; adequate fit ≤ .10 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). Indirect effects with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for each of the mediation models. In addition, a chi-square difference test was used to compare the partial mediation and full mediation models, as these models were nested. Akaike Criterion Index (AIC) values were also used to compare the partial and full mediation models (lower values suggest better fit) as was the amount of variance accounted for in the suicidal behavior latent variable.

Results

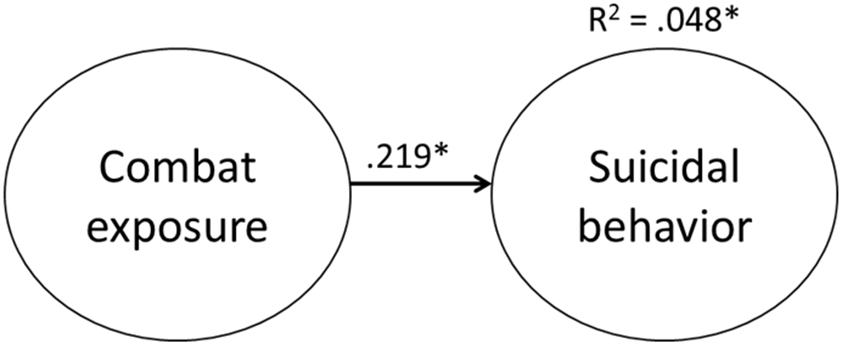

See Table 1 for sample characteristics. Fit indices for each of the models examined are displayed in Table 2. Model A (Figure 1), which examined the direct association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior exhibited excellent fit to the data, RMSEA = .027; CFI = .997, and demonstrated a positive direct association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior, β = .22, p < .001. Model B, which examined the direct association between combat exposure and PTSD-depressive symptoms, exhibited good fit to the data, RMSEA = .065, CFI = .991, and demonstrated a positive direct association between combat exposure and PTSD-depressive symptoms, β = .51, p < .001. Model C, which examined the direct association between PTSD-depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior, exhibited relatively poor fit to the data, RMSEA = .089, CFI = .976, but still demonstrated a strong direct association between PTSD-depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior, β = .58, p < .001.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| % | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 79.7% | 2,577 | |

| Female | 20.3% | 655 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 49.2% | 1575 | |

| Black | 48.8% | 1560 | |

| American Indian | 2.1% | 68 | |

| Asian | 1.3% | 43 | |

| Pacific Islander | 0.5% | 17 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 94.7% | 3011 | |

| Hispanic | 5.3% | 168 | |

| Diagnostic History | |||

| Current Depression | 19.9% | 596 | |

| Lifetime Depression | 40.6% | 1215 | |

| Current Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 30.6% | 914 | |

| Lifetime Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 39.3% | 1176 | |

| Suicidal Behavior | |||

| Lifetime Suicide Attempt | 9.0% | 292 |

Table 2.

Goodness-of-Fit Indices for the Different Structural Equation Models

| Model | χ2 | df |

p- value |

RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI |

SRMR | CFI | TLI | AIC | Suicidal Behavior R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A: Direct Effect of Combat on Suicidal Behavior | 27.322 | 8 | .0006 | .027 | .017 - .039 | .010 | .997 | .995 | 59592.1 | .05 |

| Model B: Direct Effect of Combat on PTSD-Depressive Sx | 116.963 | 8 | < .0001 | .065 | .055 - .076 | .023 | .991 | .983 | 101472.6 | n/a |

| Model C: Direct Effect of PTSD-Depressive Sx on Suicidal Behavior | 214.797 | 8 | < .0001 | .089 | .079 - .100 | .036 | .976 | .955 | 83428.7 | .34 |

| Model D: Hypothesized Full Mediation Model | 425.005 | 25 | < .0001 | .070 | .065 - .076 | .037 | .973 | .961 | 121527.9 | .32 |

| Model E: Partial Mediation Model | 406.789 | 24 | < .0001 | .070 | .064 - .076 | .033 | .974 | .961 | 121511.7 | .33 |

| Partial Mediation Model with Ideation as DV | 306.627 | 17 | < .0001 | .073 | .066 - .080 | .028 | .980 | .967 | 118584.5 | .32 |

| Partial Mediation Model with Attempt as DV | 146.901 | 12 | <.0001 | .059 | .051 - .068 | .023 | .989 | .980 | 102359.6 | .07 |

Note. df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Residual; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TFI = Tucker-Lewis Indices; AIC = Akaike Criterion Index.

Figure 1.

Model A: Direct effect of combat on suicidal behavior with standardized beta weights.

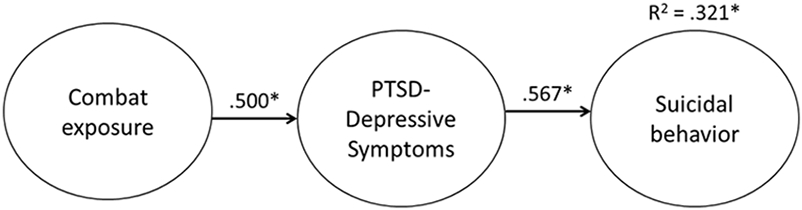

Model D (Figure 2), which tested the hypothesized full mediation model, was examined next. This model demonstrated adequate fit to the data, RMSEA = 0.070, CFI = .973. As expected, combat exposure was robustly associated with PTSD-depressive symptoms, β = .50, p < .001, which was, in turn, strongly associated with suicidal behavior, β = .57, p < .001. In addition, as hypothesized, combat exposure was found to have a significant indirect effect on suicidal behavior via PTSD-depressive symptomatology, β = .28, p < .001, 95% CI: .26 - .31.

Figure 2.

Model D: Hypothesized full mediation model with standardized beta weights.

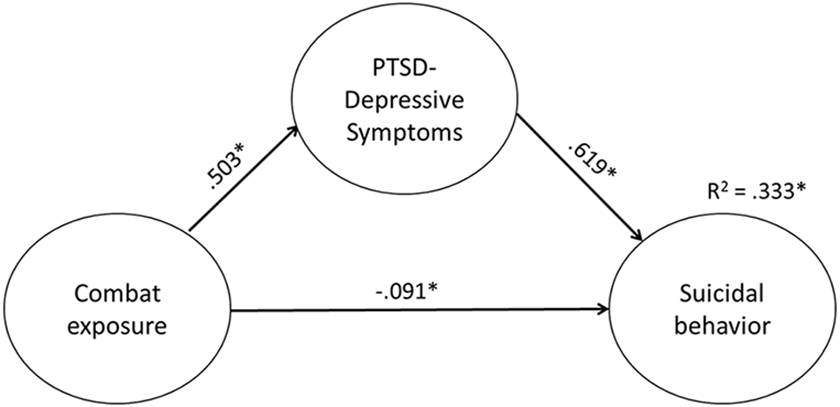

Model E (Figure 3), which tested a partial mediation model, was examined last. This model demonstrated similar fit to the data as Model D, RMSEA = 0.070, CFI = .974. In addition, as with Model D, combat exposure was robustly associated with PTSD-depressive symptoms, β = .50, p < .001, which was, in turn, strongly associated with suicidal behavior, β = .62, p < .001. Combat exposure also exhibited a significant indirect effect on suicidal behavior via PTSD-depressive symptomatology within this model, β = .31, p < .001, 95% CI: .28 - .34; however, in contrast to expectations, a significant negative direct effect between combat exposure and suicidal behavior was observed, β = −.09, p < .001. Moreover, a chi-square difference test, χ2D = 18.216, p < .001, indicated that adding the direct path from combat exposure to suicidal behavior significantly improved model fit. In addition, AIC values were substantially lower in the partial mediation model compared with the full mediation model and the partial mediation model accounted for slightly more variance in the suicidal behavior latent variable. Consequently, the partial mediation model, was retained as the final, best-fitting model.

Figure 3.

Model E: Hypothesized partial mediation model with standardized beta weights.

Additional Models Examining Ideation and Attempt as Dependent Variables

In order to determine whether Model E results were similar when using suicidal ideation instead of behavior, we ran a partial mediation model with suicidal ideation (latent factor comprised of BSS total score and BDI-II suicide item) as the dependent variable. This model demonstrated similar fit to Model E, RMSEA = 0.073, CFI = .980, and had similar results. Combat exposure was robustly associated with PTSD-depressive symptoms, β = .50, p < .001, which was, in turn, strongly associated with suicidal ideation, β = .60, p < .001. The indirect effect between combat exposure and suicidal ideation via PTSD-depressive symptomatology was, β = .30, p < .001, 95% CI: .28 - .33. Similar to Model E, a significant negative direct effect between combat exposure and suicidal ideation was observed, β = −.09, p < .001.

We also ran a partial mediation model with past suicide attempt (BSS item 20) as the dependent variable. Again, statistical fit was similar to Model E, RMSEA = 0.059, CFI = .989. Results were also similar to Model E. Combat exposure was associated with PTSD-depressive symptoms, β = .51, p < .001, which was, in turn, associated with suicide attempt, β = .31, p < .001. The indirect effect between combat exposure and suicide attempt via PTSD-depressive symptomatology was, β = .16, p < .001, 95% CI: .13 - .18. Again, a significant negative direct effect between combat exposure and suicidal behavior was found, β = −.11, p < .001.

Discussion

Taken together, the findings from the present study provide support for the hypothesis that combat exposure primarily influences risk for suicidal behavior through its effects on PTSD-depressive symptomatology. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an indirect link between general combat exposure and suicide risk via mental health symptoms, although prior research by Maguen et al. (2011) indicated that at least one aspect of combat exposure (i.e., killing in combat) is indirectly associated with suicidal behavior via PTSD-depressive symptomatology. In many ways, the indirect association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior that we observed is not surprising, given the extensive literature documenting strong associations between combat exposure and PTSD and depressive symptoms (e.g., Cabrera, Hoge, Bliese, Castro, & Messer, 2007; Hoge et al., 2004; Kimbrel et al., 2015; Kimbrel, Evans, et al., 2014; Luxton, Skopp, & Maguen, 2010). Additionally, previous literature has documented that PTSD and depressive symptoms are, in turn, associated with suicidal behavior (e.g. Jakupcak et al., 2009; Kimbrel, Calhoun, et al., 2014; Kimbrel, Meyer, et al., 2016; Ramsawh et al., 2014).

These study findings do, however, differ from those of Bryan and colleagues (2013), who did not find support for an indirect association between combat exposure and suicide risk. One potential explanation for these disparate findings is that PTSD and depression were modeled as separate factors within Bryan et al.’s path analysis model whereas the present study modeled these constructs together in a single latent factor. As noted above, there is growing evidence that PTSD and depression load onto a higher-order distress latent factor, which is strongly predictive of suicide among veterans (Kimbrel, Calhoun, et al., 2014; Kimbrel, Johnson, et al., 2014; Kimbrel, Meyer, et al., 2016). The findings from the current study offer additional support for a PTSD-depression latent factor, indicating that the combination of high levels of PTSD and depressive symptoms represented a significant risk factor for suicidal behavior in veterans.

Unexpectedly, the present research also revealed a small but statistically significant negative direct association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior within the partial mediation model. While we have previously demonstrated a significant positive association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior in an independent sample of Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans (Kimbrel, DeBeer, Meyer, Gulliver, & Morissette, 2016), the present research is the first study that we are aware of to demonstrate both a positive indirect association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior via PTSD-depressive symptomatology as well as a negative direct association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior. Notably, in the direct effect model between combat exposure and suicidal behavior, there was a significant positive association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior. This robust positive indirect effect suggests that, consistent with our primary hypothesis, combat exposure primarily affects risk for suicidal behavior by increasing veterans’ risk for PTSD and depression, which are known risk factors for suicidal behavior. However, the negative direct effect identified in the partial mediation model suggests that combat exposure was associated with decreased risk for suicidal behavior among the highly resilient subset of veterans who experience high levels of combat but do not go on to develop PTSD and depression. One potential explanation for this finding is that these veterans experienced greater posttraumatic growth. Prior research has found that higher levels of posttraumatic growth are associated with less suicidal ideation, suggesting that for some servicemembers exposure to combat experiences may lead to positive changes and an enhanced appreciation for life, which is protective against suicide (Bush, Skopp, McCann, & Luxton, 2011; Gallaway, Millikan, & Bell, 2011). It also possible that the timing of assessments impacted our findings, as prior research has found that service members are more likely to report mental health symptoms several months post-deployment than immediately post-deployment (Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007). Unfortunately, we did not assess the length of time passed since combat exposure in our dataset. Further research is necessary to examine whether the timing of assessments influences the association between combat exposure and suicide.

A potential explanation for the differences in findings observed between the present study and many of the previous studies examining the association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior (e.g., Bryan et al., 2013; Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Young-McCaughon, & Peterson, 2015; LeardMann et al., 2013) is that the present study is the first to simultaneously model both the direct and indirect paths from combat exposure to suicidal behavior. What is not clear, however, is why combat exposure had a negative direct association with suicidal behavior in the partial mediation model, as one of the leading theories of suicide (i.e., IPTS; Joiner, 2005) posits that combat exposure would increase risk for suicidal behavior by increasing veterans’ acquired capability for self-directed violence. When we examined lifetime suicide attempt as the sole outcome variable, this negative direct association remained, indicating that combat exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of self-directed violence. Unfortunately, it is difficult to make any strong inferences about this finding, because we do not know whether the suicide attempt occurred before or after exposure to combat. Thus, while the present findings are intriguing, additional studies aimed at replicating the present findings as well as extending them by identifying additional mechanisms through which combat exposure might decrease risk for suicidal behavior are needed.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations. First, the research was cross-sectional, which prevents us from making causal inferences about the relationships between the variables. Studies utilizing longitudinal designs are needed to address this research question. Additionally, as mentioned above, the inclusion of lifetime suicide attempts in the outcome variable makes it difficult to determine temporal order, as it is unknown whether suicide attempts occurred before or after combat exposure. However, this concern is somewhat reduced by our finding that the partial mediation model that did not include lifetime attempt in the outcome had very similar results to Model E. Another limitation was the use of self-report questionnaires to measure combat exposure and suicidal behavior, as self-report instruments are susceptible to the effects of memory or reporting bias. Prospective research designs and the use of a clinical interviews could help to guard against such concerns in future research.

Future research aimed at further delineating the association between combat exposure, PTSD-depressive symptomatology, and suicidal behavior is needed. For example, Maguen and colleagues demonstrated that killing in combat is uniquely associated with suicidal ideation (2012) and that this relationship is partially mediated by PTSD and depressive symptoms (2011). Other morally injurious wartime experiences have also been associated with increased risk of negative mental health outcomes and suicidal behavior (Wisco et al., 2017). The emotions of guilt and shame have also been related to PTSD (Cunningham, Davis, Wilson, & Resick, 2017), depression (Kim, Thibodeau, & Jorgensen, 2011), and suicidal ideation (Bryan et al., 2015). There is growing evidence that these emotions have a mediating effect on the relationship between PTSD and suicidal behavior (Cunningham, Farmer, et al., 2017). Future research aimed at elucidating the associations between specific aspects of combat exposure, moral injury, PTSD-depressive symptomatology, emotions such as shame and guilt, and suicidal behavior is needed.

Summary and Clinical Implications

The current study has several important clinical implications. First, the findings from the present research suggest that the association between combat exposure and suicidal behavior is complex and may contain multiple pathways. Second, our findings suggest that combat exposure exerts a significant indirect effect upon suicidal behavior via PTSD-depressive symptomatology. Third, consistent with several other recent studies in this area, our findings suggest that Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans with high levels of PTSD-depressive symptoms are at substantially increased risk for suicidal behavior. Fourth, considering the finding that combat is indirectly related to suicide via PTSD and depression, reducing these symptoms may indirectly lead to reductions in suicidal behavior. Although exposure to combat is an unpleasant reality that many of our service members face, there are treatments that exist, such as Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2016) and Prolonged Exposure (PE; Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007), that may help to ease associated distress and mitigate the risk of suicide. Indeed, there are already data in civilian (Gradus, Suvak, Wisco, Marx, & Resick, 2013) and military (Bryan et al., 2015) samples to suggest that this is the case; however, there remains a significant need for additional research aimed at identifying optimal treatments to reduce the risk of suicidal behavior among veterans with comorbid PTSD and depression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), the Research and Development and Mental Health Services of the Durham VA Medical Center, grant #11S-RCS-009 and #1IK2CX000718 (ED) from the Clinical Science Research and Development (CSR&D) Service of Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development (VA ORD), and grant #1IK2RX000703, #1lK2RX000908, and #1lK2RX001298 from the Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) Service of VA ORD. Manuscript preparation was partially supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment (Drs. Dillon, Cunningham, and Wilson). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA or the United States government or any of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

References

- Beck AT, & Steer RA (1991). Manual for Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown G (1996). Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Brancu M, Wagner HR, Morey RA, Beckham JC, Calhoun PS, Tupler LA, … VA Mid-Atlantic MIRECC Workgroup. (2017). The post-deployment mental health (PDMH) study and repository of American Afghanistan and Iraq era veterans. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, E-published ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Hernandez AM, Mintz J, Peterson AL, Yarvis JS, … Consortium, S. S. (2016). Evaluating Potential Iatrogenic Suicide Risk in Trauma-Focused Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Treatment of Ptsd in Active Duty Military Personnel. Depression and Anxiety, 33(6), 549–557. doi: 10.1002/da.22456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Hernandez AM, Allison S, & Clemans T (2013). Combat exposure and suicide risk in two samples of military personnel. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 64–77. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Roberge E, Bryan AO, Ray-Sannerud B, Morrow CE, & Etienne N (2015). Guilt as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Depression and Posttraumatic Stress With Suicide Ideation in Two Samples of Military Personnel and Veterans. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 143–155. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000358077100005 [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Wertenberger E, Young-McCaughon S, & Peterson A (2015). Nonsuicidal self-injury as a prospective predictor of suicide attempts in a clinical sample of military personnel. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 59, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush NE, Skopp NA, McCann R, & Luxton DD (2011). Posttraumatic growth as protection against suicidal ideation after deployment and combat exposure. Military Medicine, 176(11), 1215–1222. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22165648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera OA, Hoge CW, Bliese PD, Castro CA, & Messer SC (2007). Childhood adversity and combat as predictors of depression and post-traumatic stress in deployed troops. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 33(2), 77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Resnick H, & Kilpatrick DG (2009). Does prior exposure to interpersonal violence increase risk of PTSD following subsequent exposure. Behavior Research and Therapy, 47, 1012–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Clara IP, & Enns MW (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the structure of common mental disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 15(4), 168–171. doi: 10.1002/da.10052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KC, Davis JL, Wilson SM, & Resick PA (2017). A relative weights comparison of trauma-related shame and guilt as predictors of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity among US veterans and military members. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KC, Farmer C, LoSavio ST, Dennis PA, Clancy CP, Hertzberg MA, … Beckham JC (2017). A model comparison approach to trauma-related guilt as a mediator of the relationship between PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation among veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221, 227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, … Feldman ME (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale for posttraumatic stress disorder: The Davidson Trauma Scale. Psychological Medicine, 27, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, & Pincus HA (2002). The DSM-IV Text Revision: Rationale and potential impact on clinical practice. Psychiatry Services, 53(3), 288–292. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.3.288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, & Rothbaum BO (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences, therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaway MS, Millikan AM, & Bell MR (2011). The association between deployment-related posttraumatic growth among U.S. Army soldiers and negative behavioral health conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(12), 1151–1160. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradus JL, Suvak MK, Wisco BE, Marx BP, & Resick PA (2013). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder reduces suicidal ideation. Depression and Anxiety, 30(10), 1046–1053. doi: 10.1002/da.22117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, & Castro CA (2012). Preventing suicides in US service members and veterans: concerns after a decade of war. The Journal of American Medical Association, 308(7), 671–672. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, & Koffman RL (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Cook J, Imel Z, Fontana A, Rosenheck R, & McFall M (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(4), 303–306. doi: 10.1002/jts.20423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr. (2005). Why do people die by suicide? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM, Zimering RT, Taylor KL, & Mora CA (1989). Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1, 53–55. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.1.1.53 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Thibodeau R, & Jorgensen RS (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: a meta-analytic review. Psychology Bulletin, 137(1), 68–96. doi: 10.1037/a0021466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Calhoun PS, Elbogen EB, Brancu M, Mid-Atlantic VA MIRECC Registry Workgroup, & Beckham JC (2014). The factor structure of psychiatric comorbidity among Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans and its relationship to violence, incarceration, suicide attempts, and suicidality. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (2016). Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans. Psychiatry Research, 243, 232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Silvia PJ, Beckham JC, Young KA, & Morissette SB (2015). An examination of the broader effects of warzone experiences on returning Iraq/Afghanistan veterans′ psychiatric health. Psychiatry Research, 226(1), 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Evans LD, Patel AB, Wilson LC, Meyer EC, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (2014). The critical warzone experiences (CWE) scale: Initial psychometric properties and association with PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Psychiatry Research, 220(3), 1118–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Johnson ME, Clancy C, Hertzberg M, Collie C, Van Voorhees EE, … Beckham JC (2014). Deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation among male Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans seeking treatment for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(4), 474–477. doi: 10.1002/jts.21932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (2016). A 12-Month prospective study of the effects of PTSD-depression comorbidity on suicidal behavior in Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans. Psychiatry Research, 243, 97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Principles and practice of Structural Equation Modeling (2 ed.). New York: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, Bell MR, Smith B, Boyko EJ, … Hoge CW (2013). Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. Journal of American Medical Assocation, 310(5), 496–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.65164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton DD, Skopp NA, & Maguen S (2010). Gender differences in depression and PTSD symptoms following combat exposure. Depression and Anxiety, 27(11), 1027–1033. doi: 10.1002/da.20730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Gahm GA, Reger MA, Metzler TJ, & Marmar CR (2011). Killing in combat, mental health symptoms, and suicidal ideation in Iraq war veterans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Metzler TJ, Bosch J, Marmar CR, Knight SJ, & Neylan TC (2012). Killing in combat may be independently associated with suicidal ideation. Depression and Anxiety, 29(11), 918–923. doi: 10.1002/da.21954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Fogler JM, Wolf EJ, Kaloupek DG, & Keane TM (2008). The internalizing and externalizing structure of psychiatric comorbidity in combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(1), 58–65. doi: 10.1002/jts.20303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, & Hoge CW (2007). Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(18), 2141–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo M, Brent DA, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, … Mann J (2005). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Comorbid With Major Depression: Factors Mediating the Association With Suicidal Behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(3), 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Friend JM, Halberstam B, Brodsky BS, Burke AK, Grunebaum MF, … Mann JJ (2003). Association of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression with greater risk for suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 580–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Acosta J, Burns RM, Jaycox LH, & Pernin CG (2011). The War Within: Preventing Suicide in the U.S. Military. Rand Health Quarterly, 1(1), 2. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28083158 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsawh HJ, Fullerton CS, Mash HB, Ng TH, Kessler RC, Stein MB, & Ursano RJ (2014). Risk for suicidal behaviors associated with PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in the U.S. Army. Journal of Affective Disorders, 161, 116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick P, Monson C, & Chard K (2016). Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD (2006). Fluid vulnerability theory: A cognitive approach to understanding the process of acute and chronic risk. In Ellis TE (Ed.), Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy (pp. 355–368). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Bender TW, Ribeiro JD, Nock MK, Rudd MD, … Joiner TE Jr. (2010). Overcoming the fear of lethal injury: evaluating suicidal behavior in the military through the lens of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco BE, Marx BP, May CL, Martini B, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, & Pietrzak RH (2017). Moral injury in U.S. combat veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depression & Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.22614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]