Abstract

Quinupristin-dalfopristin is a streptogramin combination active against multiply resistant Enterococcus faecium. Among 45 E. faecium isolated from patients in various French hospitals, only two strains were intermediate (MIC = 2 μg/ml) and one, E. faecium HM1032, was resistant (MIC = 16 μg/ml) to quinupristin-dalfopristin, according to British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards approved breakpoints. The latter strain contained the vgb and satA genes responsible for hydrolysis or acetylation of quinupristin and dalfopristin, respectively, and an ermB gene (also previously referred to as ermAM) encoding a ribosomal methylase. The two intermediate strains had an LSA phenotype characterized by resistance to lincomycin (L), increased MICs (≥8 μg/ml) of dalfopristin (streptogramin A [SA]), and susceptibility to erythromycin and quinupristin. This phenotype was also detected in eight other strains susceptible to quinupristin-dalfopristin. No genes already known and conferring resistance to dalfopristin by acetylation or active efflux were detected in these LSA strains. Nineteen other strains resistant to erythromycin but susceptible to the quinupristin-dalfopristin combination displayed elevated MICs of quinupristin after induction (from 16 to >128 μg/ml) and contained ermB genes. The effects of ermB, vgb, and satA genes on the activity of the streptogramin combination were tested by cloning these genes individually or in various combinations in recipient strains susceptible to quinupristin-dalfopristin, E. faecium HM1070 and Staphylococcus aureus RN4220. The presence of both the satA and vgb genes (regardless of the presence of an ermB gene) was necessary to confer full quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance to the host. The same genetic constructs were introduced into E. faecium BM4107 which displays a LSA phenotype. Addition of the satA or vgb gene to this LSA background conferred resistance to quinupristin-dalfopristin.

In recent years, enterococci have become one of the most common causes of nosocomial infections, while certain strains have acquired resistance to all available antimicrobial agents, including aminoglycosides, penicillins, and glycopeptides. Quinupristin-dalfopristin is an antimicrobial combination developed for the treatment of infections due to vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (20). This antimicrobial belongs to the streptogramin class which includes naturally synthesized antibiotics composed of two chemically distinct factors, streptogramins A (SA) and streptogramins B (SB). Quinupristin-dalfopristin is a semisynthetic injectable streptogramin mixture of quinupristin (SB) and dalfopristin (SA) in a 30:70 ratio (9). Binding of these factors to the 50S ribosomal subunit causes inhibition of protein synthesis (37). Alone, each factor has a moderate bacteriostatic activity, but in combination, they often display a bactericidal synergistic effect (9). This is related to the synergistic binding of the factors to their ribosomal target site. Each factor binds a different site on the peptidyltransferase domain of the ribosome, but the binding of SA causes a conformational change which increases the affinity of SB for its target (36). Since SA and SB are chemically unrelated and have different binding sites, the mechanisms of resistance to these two streptogramin types are different. In E. faecium, an acetyltransferase encoded by the satA gene inactivates streptogramins A (31). After completion of this work, a new satG gene encoding a putative acetyltransferase which appeared to be prevalent in E. faecium was reported (39). Both genes are related to the acetyltransferase genes vat (7), vatB (2), and vatC (4) reported in staphylococci. Resistance to streptogramins B is due either to hydrolysis of the antibiotic mediated by the vgb gene (12, 23) initially reported in Staphylococcus aureus (6) or to modification of the ribosomal target by a 23S rRNA methylase encoded by the ermB gene (24, 38). Other staphylococcal genes such as vga and vgaB conferring resistance to SA by a putative efflux mechanism (3, 5) or msrA encoding a protein which participates in the active efflux of macrolides and SB (34) have not been reported in enterococci.

Because of the synergism displayed by the two streptogramin types, it has been suggested that acquisition of isolated resistance to dalfopristin or quinupristin could have no or only partial negative impact on the antimicrobial activity of the combination (13, 25). In fact, it has been shown that inhibitory synergy between the two factors is maintained in vitro against E. faecium strains resistant to quinupristin by synthesis of a ribosomal methylase (19). However, the consequences of inactivation of dalfopristin or quinupristin or the outcome of combined mechanisms of resistance on the activity of quinupristin-dalfopristin have not been systematically analyzed.

We have studied the activity of quinupristin-dalfopristin against 45 clinical strains of E. faecium isolated from patients in different French hospitals in relation to the mechanisms of resistance to quinupristin and dalfopristin. Recombinant plasmids containing the three streptogramin resistance genes well characterized in enterococci, ermB, satA, and vgb alone or in all possible combinations, were also constructed. The plasmids were introduced into E. faecium and S. aureus to evaluate the impact of the various resistance mechanisms on the activity of quinupristin-dalfopristin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Forty-five clinical isolates of E. faecium isolated from patients in 16 French hospitals in 1995 and identified according to the scheme of Facklam and Collins (17) were included in the study. E. faecium strains resistant to lincomycin and dalfopristin were further identified by amplification of the d-Ala–d-Ala ligase gene (ddl) specific to this species to differentiate them from Enterococcus faecalis, which is intrinsically resistant to both antibiotics (12). E. faecium HM1070 and S. aureus RN4220 (18), which are susceptible to macrolides, lincosamides, SA, and SB, and E. faecium BM4107 (26), which was resistant to lincomycin and SA by an unknown mechanism, were used as recipient strains in the transformation experiments. S. aureus BM3002 (vat vgb vga) and Streptococcus pneumoniae HM30 (ermB) (32) were used as control strains for PCR and hybridization experiments.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Antibiotic susceptibility was tested by the disk diffusion technique, and MICs of antibiotics were determined by the agar dilution method using Mueller-Hinton medium (Sanofi-Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) according to the recommendations of the Comité de l’Antibiogramme de la Societé Française de Microbiologie (14). The enterococcal strains were grown overnight without antibiotics or induced with quinupristin (1 μg/ml). MICs of erythromycin, quinupristin, dalfopristin, and quinupristin-dalfopristin were determined for induced and noninduced cells. Proposed British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards breakpoints (susceptible, MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml; resistant, MIC ≥ 4 μg/ml) were used for quinupristin-dalfopristin (10).

Inactivation of antibiotics.

In all clinical isolates of E. faecium, inactivation of quinupristin, dalfopristin, and erythromycin by bacterial cells was screened for by the microbiological method of Gots, using Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341 as an indicator organism and brain heart infusion agar plates containing dalfopristin (0.5 μg/ml), quinupristin (1 μg/ml), or erythromycin (0.2 μg/ml) (21).

Characterization of streptogramin resistance genes.

The resistance genes were amplified by PCR using oligonucleotide primers described previously. Primers I and J, universal for streptogramin A acetyltransferase genes (2), were used to amplify a 144-bp DNA fragment within the vat and satA genes or a 147-bp fragment within the vatB gene. Primers A and B were used to specifically amplify a portion of the vga gene, and primers C and D were used to amplify a 920-bp fragment of the vgb gene (28). Primers I and II were used to amplify 639 bp of ermB genes (35). DNA fragments amplified with primers I and J and primers C and D were sequenced by an automated ABI PRISM 377 system (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, Conn.). The erm amplicons were denatured for 10 min in a boiling water bath, immediately cooled on ice for 5 min, immobilized on Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham France, Les Ullis, France) by UV light, and then hybridized with probe made of an internal fragment of the ermB gene of S. pneumoniae HM30 amplified by PCR and labeled with digoxigenin (Boehringer Mannheim France, Meylan, France).

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

The satA, vgb, and ermB genes preceded by their putative promoters were amplified from E. faecium HM1032 DNA by PCR with the oligonucleotides shown in Table 1. The gene sequences were determined and were >95% identical to the published sequences of satA (31), vgb (6), and ermB (33) genes. The oligonucleotides were modified by insertion of restriction enzyme recognition sites for cloning in pUC18. PCR was done as follows: (i) an initial step of 5 min at 94°C, (ii) 35 cycles of PCR, with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C, and (iii) a final step of 12 min at 72°C. The amplification products were digested with the appropriate enzymes and cloned separately in Escherichia coli DH10B. Plasmids containing combinations of resistance genes in the 5′-to-3′ orientation and in the following order, satA-ermB, satA-vgb, vgb-ermB, and satA-vgb-ermB were constructed. In a second step, the inserts were subcloned in the shuttle multicopy vector, pJIM2246 (chloramphenicol resistant) (30), into E. coli DH10B and then introduced by transformation into E. faecium HM1070, E. faecium BM4107 (22), and S. aureus RN4220 (32). In these constructs, the cloned genes were under the control of the promoter of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene of plasmid pJIM2246 and satA and ermB were under the control of their own putative promoter. In strains containing satA and/or vgb, inactivation of dalfopristin and/or quinupristin was checked.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for amplification of the satA, vgb, and ermB genes

| Amplified gene (positiona of the structural gene) | Size (bp) of PCR product | Primer | Sequence of primerb | Positiona | Inserted restriction site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| satA (162–791) | 770 | SATSACI | 5′ GTTGAGCTCATAAAATTTGTACAGG 3′ | 35–59 | SacI |

| SATBAMI | 5′ TTTTAGGATCCTTATCATTTTTTCC 3′ | 805–780 | BamHI | ||

| vgb (641–1540) | 966 | VGBBAMI | 5′ GAGATGGATCCTATTTTTGTTTTGG 3′ | 584–608 | BamHI |

| VGBSALI | 5′ TTCAGTCGACTCACTCCATATTATCC 3′ | 1550–1525 | SalI | ||

| ermB (318–1055) | 1,048 | ERMSALI | 5′ GTGTGTCGACAGTGCATTATCTTAA 3′ | 20–44 | SalI |

| ERMPSTI | 5′ CGACCTGCAGAATTATTTCCTCCC 3′ | 1044–1068 | PstI |

RESULTS

Characterization of the phenotypes and mechanisms of resistance to quinupristin and dalfopristin.

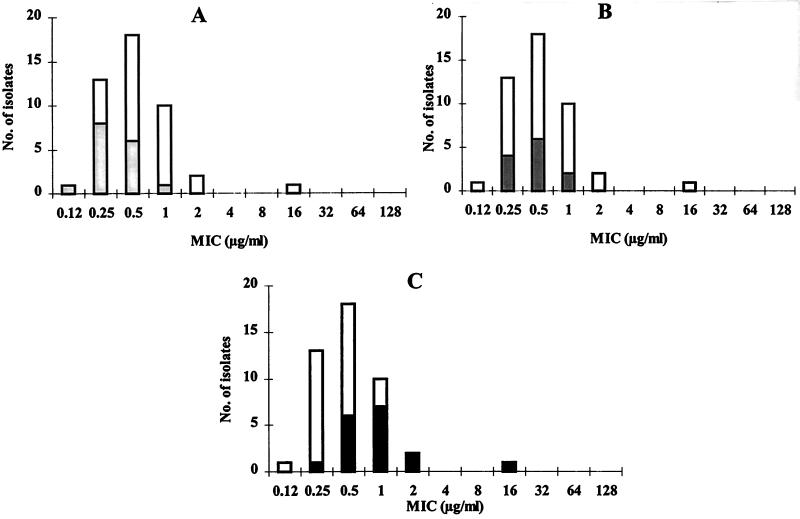

The distribution of quinupristin and dalfopristin MICs for E. faecium clinical isolates is shown in Fig. 1. The MICs at which 50 and 90% of the isolates are inhibited were equal to 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, respectively. Only one strain, E. faecium HM1032, was resistant to the streptogramin (MIC = 16 μg/ml), and two were intermediate (MIC = 2 μg/ml). On the basis of susceptibility to erythromycin, lincomycin, quinupristin, and dalfopristin, a susceptible phenotype and three resistance phenotypes, macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance (MLSB), LSA, MLSB SA could be distinguished (Table 2). Sixteen strains had the susceptible phenotype characterized by susceptibility to erythromycin (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml), lincomycin (inhibition zone diameters of ≥21 mm), quinupristin-dalfopristin (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml), and by an MIC of quinupristin or dalfopristin of less than 8 μg/ml. The MLSB phenotype category which corresponds to cross-resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and SB but susceptibility to SA (38) included 12 strains which contained an ermB gene as shown by PCR and hybridization experiments. Quinupristin MICs (SB) ranged from 1 to 64 μg/ml but increased by 4 to 16 times after growth in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of this antibiotic for nearly all the strains, indicating that this phenotype was most often inducible. Against strains with an MLSB phenotype, the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin, in comparison with those against the susceptible isolates was not altered, even after induction with quinupristin (Table 2). The LSA phenotype (10 strains) was characterized by susceptibility to erythromycin together with resistance to lincomycin and elevated MICs of dalfopristin (≥ 8 μg/ml). No gene responsible for inactivation or efflux was found by PCR, and no inactivation of dalfopristin was detected. The LSA phenotype resulted in no or in a slight increase in the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin which led to the classification of two strains as intermediate according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards breakpoints (Fig. 1). Finally, association of MLSB with SA resistance resulted in the MLSB SA phenotype in seven strains. As expected, these isolates contained ermB-like genes, but six did not harbor any gene known to confer resistance to SA. In the latter strains, the MLSB SA phenotype could result from the presence of MLSB and LSA determinants. In the seventh strain, E. faecium HM1032 resistant to quinupristin-dalfopristin, coexistence of ermB-, satA-, and vgb-related genes was found. Sequence determination of the fragments amplified with primers specific for the satA and vgb genes revealed greater than 95% identity with the prototype genes (6, 31). E. faecium HM1032 was also resistant to vancomycin and teicoplanin due to the presence of the vanA gene cluster as shown by PCR (15). Thus, resistance to the combined streptogramins was observed for a single strain among 45, combining a minimum of three mechanisms of resistance to SA and SB.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of MICs of quinupristin and dalfopristin for E. faecium strains according to the phenotype of resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins. MIC distribution is shown for all the strains (white bars) and for particular phenotypes, namely, quinupristin- and dalfopristin-susceptible strains (lightly stippled bars), quinupristin-resistant (MLSB phenotype) and dalfopristin-susceptible strains (medium stippled bars), and dalfopristin-resistant strains (MICs ≥ 8 μg/ml) (quinupristin-resistant or -susceptible) (black bars).

TABLE 2.

Ranges of MICs of quinupristin, dalfopristin, and quinupristin-dalfopristin for E. faecium by phenotype and genotype

| Phenotype (no. of strains) | Detected gene(s)a (no. of strains) | MIC range (μg/ml) of drug(s)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinupristin

|

Dalfopristin | Quinupristin-dalfopristinc | |||

| Not induced | Inducedb | ||||

| Susceptible (16) | None (16) | 0.25–4 | 0.25–4 | 0.5–2 | 0.125–1 |

| MLSB (12) | ermB (12) | 1–64 | 16–>128 | 1–2 | 0.25–1 |

| LSA (10) | None (10) | 0.25–16 | 0.25–16 | 8–>128 | 0.25–2 |

| MLSB SA (7) | ermB (6) | 2–32 | 16–>128 | 8–>128 | 0.5–1 |

| ermB, vgb, satA (1) | 64 | >128 | >128 | 16 | |

The presence of ermB, vgb, satA, vat, vatB, and vga genes was verified by PCR.

Induction was done by growing bacteria overnight in medium containing 1 μg of quinupristin per ml.

MICs of quinupristin-dalfopristin for enterococci were the same whether or not the bacterial cells were induced with quinupristin.

Impact of combinations of ermB, satA, and vgb genes on the activity of quinupristin-dalfopristin.

The ermB, satA, and vgb genes from E. faecium HM1032 were amplified by PCR and cloned alone or in all possible combinations in the shuttle vector pJIM2246. The constructs were then introduced into E. faecium BM4107, E. faecium HM1070, and S. aureus RN4220. Plasmid-free E. faecium BM4107 was used, in addition to the other two plasmid-free recipients susceptible to SA and SB, since this strain displayed an LSA phenotype which appeared to be prevalent in clinical isolates of E. faecium. This strain was resistant to lincomycin (MIC = 16 μg/ml) and dalfopristin (MIC = 128 μg/ml) and susceptible to quinupristin (MIC = 2 μg/ml) and quinupristin-dalfopristin (MIC = 1 μg/ml) and did not contain any known gene of resistance to SA or SB. The MICs of streptogramins for the transformants and the recipients containing plasmid pJIM2246 as controls are shown in Table 3. The presence of an inducible ermB gene led to an increase in the MIC of quinupristin (SB) which was enhanced after induction with quinupristin (1 μg/ml) from twofold in E. faecium HM1070(pJIM2246) ΩermB to eightfold in S. aureus RN4220 and E. faecium(pJIM2246) ΩermB. As expected, the activity of dalfopristin (SA) was not affected, and there was no change in the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin, even after induction with quinupristin (SB) (data not shown). However, the moderate level of resistance to quinupristin conferred by the ermB gene in the E. faecium HM1070 background is a limitation to the interpretation of the impact of the gene on the activity of the combination against this strain. Hydrolysis of quinupristin mediated by the vgb gene led to a fourfold increase in the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin for E. faecium HM1070 and S. aureus RN4220; however, the transformants remained susceptible to the antimicrobial combination. Acetylation of dalfopristin due to the satA gene resulted in an eightfold increase in the MIC of this antibiotic for E. faecium HM1070 and S. aureus RN4220 but in only a one-dilution increase in MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin. Thus, the presence of only one of these mechanisms of resistance to SA or SB was not sufficient to confer resistance to the streptogramin combination. The presence of the ermB and vgb genes did not result in a further increase in the level of resistance to quinupristin. Combination of the ermB gene with satA yielded a one- or two-dilution increase in the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin and led to classification of E. faecium HM1070(pJIM2246) Ω(ermB satA) as intermediate. Only coexistence of the satA and vgb genes conferred quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance.

TABLE 3.

MICs of quinupristin, dalfopristin, and quinupristin-dalfopristin for three recipient strains containing the ermB, satA, and vgb genes cloned in various combinations on plasmid pJIM2246

| Strain and plasmid | MIC (μg/ml) of drug(s)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinupristin

|

Dalfopristin | Quinupristin-dalfopristinb | ||

| Not induced | Induceda | |||

| E. faecium HM1070 | ||||

| pJIM2246 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| pJIM2246 ΩermB | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 (1) |

| pJIM2246 ΩsatA | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 (2) |

| pJIM2246 Ωvgb | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB satA) | 2 | 4 | 32 | 2 (8) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB vgb) | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(satA vgb) | 8 | 8 | 32 | 4 (16) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB satA vgb) | 16 | 16 | 32 | 4 (16) |

| E. faecium BM4107 | ||||

| pJIM2246 | 2 | 2 | >128 | 1 |

| pJIM2246 ΩermB | 4 | 32 | 128 | 1 (1) |

| pJIM2246 ΩsatA | 4 | 4 | >128 | 4 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ωvgb | 4 | 4 | 128 | 4 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB satA) | 4 | 16 | >128 | 8 (8) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB vgb) | 8 | 8 | 128 | 8 (8) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(satA vgb) | 8 | 8 | >128 | 16 (16) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB satA vgb) | 16 | 16 | >128 | 16 (16) |

| S. aureus RN4220 | ||||

| pJIM2246 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| pJIM2246 ΩermB | 2 | 16 | 1 | 0.25 (1) |

| pJIM2246 ΩsatA | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 (2) |

| pJIM2246 Ωvgb | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB satA) | 4 | 8 | 16 | 1 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB vgb) | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(satA vgb) | 8 | 8 | 16 | 4 (16) |

| pJIM2246 Ω(ermB satA vgb) | 8 | 16 | 16 | 4 (16) |

Induction was done by growing bacteria overnight in medium containing 1 μg of quinupristin per ml.

Values in parentheses are the MIC multiplication factors. The MIC multiplication factor is the ratio of the MIC for the transformant to the MIC for the recipient containing pJIM2246.

The LSA background of E. faecium BM4107 host played an important role. The presence of the satA or vgb gene alone multiplied the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin by a factor which was similar to that for the other recipient strains (Table 3). However, since the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin for E. faecium BM4107 was equal to 1 μg/ml, this increase was sufficient to confer resistance to the antimicrobial. When the resistance genes were combined, MICs increased up to 16 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that only one strain among 45 clinical isolates of E. faecium collected in France in 1995 was fully resistant to quinupristin-dalfopristin. This prevalence is similar to that reported in a previous study in the United States (16). However, in 29 of the 45 strains studied, a mechanism of resistance to quinupristin (SB) or dalfopristin (SA) was found. As observed both for clinical isolates and for isogenic pairs of strains, the presence of an ermB-like gene conferring resistance to quinupristin had no or a very weak influence on the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin. This could result from the inducible expression of the ermB-like genes in the strains studied which is common for this determinant in enterococci, pneumococci, and streptococci (33). The presence of dalfopristin (SA) could prevent synthesis of the inducible ribosomal methylase. However, the synergy between the two streptogramin factors was observed even after preinduction of the bacterial cultures with quinupristin (SB) and has been reported in staphylococci when the erm gene is expressed constitutively (38). In fact, conservation of synergism is most probably due to the mode of action of streptogramins: the factor A binds to its target and may induce a conformational change in the ribosome, leading to an increase in its affinity for factor B (13). The ribosomal alteration should be sufficiently pronounced to overcome the loss of affinity for the B molecule that results from rRNA methylation. Quinupristin modification mediated by the vgb gene had a moderate impact on the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin which remained within the susceptible clinical category. Superposition of this mechanism of resistance onto target modification did not amplify the level of resistance to quinupristin. This result differs from that reported in a strain of E. coli where the ermB and ereB (esterification of erythromycin) genes contribute to erythromycin resistance in a more than additive fashion (8).

According to the hypothesized mechanism of synergism between SA and SB mentioned above, factor A of streptogramins would have a key role in the synergy between SA and SB. Therefore, alteration of the activity of dalfopristin (SA) was expected to have a deleterious effect on synergy. In a recent study, resistance to quinupristin-dalfopristin in clinical isolates of staphylococci was always related to resistance to type A streptogramins encoded by vat or vatB genes associated with erm genes (27). Surprisingly, acetylation of dalfopristin yielded only a modest increase in the MIC of quinupristin-dalfopristin for enterococci (Table 3). The moderate level of resistance to dalfopristin conferred by the satA gene suggested that SA could in part escape chemical modification caused by the enzyme. Therefore, enough drug might bind the ribosomes to trigger synergy between SA and SB since the synergy is expressed over a wide range of quinupristin/dalfopristin ratios (11). The other type of resistance to dalfopristin was detected in the clinical strains with an LSA phenotype. This phenotype has been reported in staphylococci (1) but not in E. faecium. The mechanism of resistance remains to be elucidated in both bacterial genera. This phenotype resembles LSA resistance in E. faecalis which is intrinsic to this species. Therefore, surveillance of the prevalence of this phenotype in E. faecium requires accurate identification at the species level, including genotypic techniques if necessary (15). LSA resistance, when combined with inactivation of quinupristin (SB) or dalfopristin (SA) led to full expression of quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance. This phenotype appears nearly as prevalent as MLSB in E. faecium, but in contrast to this latter mechanism, acquisition of LSA resistance could be an important step towards resistance to quinupristin-dalfopristin. Although this study showed that a combination of a minimum of two resistance mechanisms to SA and SB was necessary to confer resistance to the streptogramin combination, the role of other unknown mechanisms conferring resistance to streptogramins in enterococci remains to be assessed. In a recent study, among 51 E. faecium resistant to quinupristin-dalfopristin isolated in farm animals and in humans, only 37 contained a satA gene and one contained a vgb gene (23). Finally, it remains to be established if the synergistic effect of quinupristin (SB) and dalfopristin (SA) which is able to overcome isolated resistance to either factor in vitro holds true in vivo. Studies in the animal model of endocarditis indicate decreased in vivo activity of quinupristin-dalfopristin against MLSB-resistant strains of E. faecium (19). However, findings of the Synercid emergency use program showed 70% successful treatment of infections due to vancomycin-resistant E. faecium despite the expression of MLS resistance in the vast majority of the strains (16, 29).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a grant from Rhône-Poulenc Rorer.

We thank Jean-François Desnottes, Michael Dowzicky, Sylvie Dutka-Malen, Céline Féger, and Harriette Nadler for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allignet J, Aubert S, Morvan A, El Solh N. Distribution of genes encoding resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds among staphylococci resistant to these antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2523–2528. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allignet J, El Solh N. Diversity among the gram-positive acetyltransferases inactivating streptogramin A and structurally related compounds and characterization of a new staphylococcal determinant, vatB. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2027–2036. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allignet J, El Solh N. Characterization of a new staphylococcal gene, vgaB, encoding a putative ABC transporter conferring resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds. Gene. 1997;202:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00464-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allignet J, Liassine N, El Solh N. Characterization of a staphylococcal plasmid related to pUB110 and carrying two novel genes, vatC and vgbB, encoding resistance to streptogramins A and B and similar antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1794–1798. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allignet J, Loncle V, El Solh N. Sequence of a staphylococcal plasmid gene, vga, encoding a putative ATP-binding protein involved in resistance to virginiamycin A-like antibiotics. Gene. 1992;117:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90488-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allignet J, Loncle V, Mazodier P, El Solh N. Nucleotide sequence of a staphylococcal plasmid gene, vgb, encoding a hydrolase inactivating the B components of virginiamycin-like antibiotics. Plasmid. 1988;20:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(88)90034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allignet J, Loncle V, Simenel C, Delepierre M, El Solh N. Sequence of a staphylococcal gene, vat, encoding an acetyltransferase inactivating the A-type compounds of virginiamycin-like antibiotics. Gene. 1993;130:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90350-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arthur M, Courvalin P. Contribution of two different mechanisms to erythromycin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:694–700. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.5.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrière J C, Berthaud N, Beyer D, Dutka-Malen S, Paris J M, Desnottes J F. Recent developments in streptogramin research. Curr Pharm Des. 1998;4:155–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. Provisional interpretive criteria for quinupristin/dalfopristin susceptibility tests. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):87–92. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouanchaud D H. In-vitro and in-vivo synergic activity and fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) of the components of a semisynthetic streptogramin, RP 59500. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30(Suppl. A):95–99. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.suppl_a.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bozdogan B, Leclercq R. Abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Intrinsic and acquired resistance to dalfopristin in Enterococcus spp., abstr C-79; pp. 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocito C, Di Giambattista M, Nyssen E, Vannuffel P. Inhibition of protein synthesis by streptogramins and related antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):7–13. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comité de l’Antibiogramme de la Societé Française de Microbiologie. 1996 report of the Comité de l’Antibiogramme de la Societé Française de Microbiologie. Technical recommendations for in vitro susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2(Suppl. 1):11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:24–27. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.24-27.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eliopoulos G M, Wennersten C B, Gold H S, Schulin T, Souli M, Farris M G, Cerwinka S, Nadler H L, Dowzicky M, Talbot G H, Moellering R C., Jr Characterization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates from the United States and their susceptibility in vitro to dalfopristin-quinupristin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1088–1092. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Facklam R R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairweather N, Kennedy S, Foster T J, Kehoe M, Dougan G. Expression of a cloned Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin determinant in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1112–1117. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1112-1117.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fantin B, Leclercq R, Garry L, Carbon C. Influence of inducible cross-resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B-type antibiotics in Enterococcus faecium on activity of quinupristin-dalfopristin in vitro and in rabbits with experimental endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:931–935. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuller R E, Drew R H, Perfect J R. Treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococci, with a focus on quinupristin/dalfopristin. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:584–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gots J S. The detection of penicillinase production properties of microorganisms. Science. 1945;102:309. doi: 10.1126/science.102.2647.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holo H, Nes I F. Transformation of lactococcus by electroporation. Methods Mol Biol. 1995;47:195–199. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-310-4:195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen L B, Hammerum A M, Aerestrup F M, Van Den Bogaard A E, Stobberingh E E. Occurrence of satA and vgb genes in streptogramin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates of animal and human origins in The Netherlands. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3330–3331. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Streptogramins: an answer to antibiotic resistance in gram-positive bacteria. Lancet. 1998;352:591–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leclercq R, Derlot E, Weber M, Duval J, Courvalin P. Transferable vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:10–15. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lina G, Quaglia A, Reverdy M E, Leclercq R, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. Distribution of genes encoding resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins among staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1062–1066. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loncle V, Casetta A, Buu-Hoi A, El Solh N. Analysis of pristinamycin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates responsible for an outbreak in a Parisian hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2159–2165. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinhardt J, Blumberg E A, Bompart F, Talbot G H. The efficacy and safety of quinupristin/dalfopristin for the treatment of infections caused by vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:251–261. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renault P, Corthier G, Goupil N, Delorme C, Ehrlich S D. Plasmid vectors for Gram-positive bacteria switching from high and to low copy number. Gene. 1996;183:175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rende-Fournier R, Leclercq R, Galimand M, Duval J, Courvalin P. Identification of the satA gene encoding a streptogramin A acetyltransferase in Enterococcus faecium BM4145. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2119–2125. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosato A, Vicarini H, Bonnefoy A, Chantot J F, Leclercq R. A new ketolide, HMR 3004, active against streptococci inducibly resistant to erythromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1392–1396. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosato A, Vicarini H, Leclercq R. Inducible or constitutive expression of resistance in clinical isolates of streptococci and enterococci cross-resistant to erythromycin and lincomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:559–562. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross J I, Eady E A, Cove J H, Cunliffe W J, Baumberg S, Wootton J C. Inducible erythromycin resistance in staphylococci is encoded by a member of the ATP-binding transport super-gene family. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1207–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutcliffe J E, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vannuffel P, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C. The role of rRNA bases in the interaction of peptidyltransferase inhibitors with bacterial ribosomes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16114–16120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vannuffel P, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C. Chemical probing of virginiamycin M-promoted conformational change of the peptidyltransferase domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4449–4453. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.21.4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner G, Witte W. Characterization of a new enterococcal gene, satG, encoding a putative acetyltransferase conferring resistance to streptogramin A compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1813–1814. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]