Abstract

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections are a worldwide health problem in need of new effective treatments. Of particular interest is the identification of antiviral agents that act via different mechanisms compared to current drugs, as these could interact synergistically with first-line antiherpetic agents to accelerate the resolution of HSV-1-associated lesions. For this study, we applied a structure-based molecular docking approach targeting the nectin-1 and herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) binding interfaces of the viral glycoprotein D (gD). More than 527,000 natural compounds were virtually screened using Autodock Vina and then filtered for favorable ADMET profiles. Eight top hits were evaluated experimentally in African green monkey kidney cell line (VERO) cells, which yielded two compounds with potential antiherpetic activity. One active compound (1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-2-[(5Z)-2H,6H,7H,8H-[1,3] dioxolo[4,5-g]isoquinoline-5-ylidene]ethenone) showed weak but significant antiviral activity. Although less potent than antiherpetic agents, such as acyclovir, it acted at the viral inactivation stage in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a novel mode of action. These results highlight the feasibility of in silico approaches for identifying new antiviral compounds, which may be further optimized by medicinal chemistry approaches.

Keywords: herpes simplex virus type 1, virtual screening, molecular docking, glycoprotein D, natural compounds

1. Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a contagious human pathogen that is estimated to affect 3.7 billion people worldwide [1]. Whereas HSV-1 infections are commonly associated with limited facial–oral lesions, severe disease can occur in neonates or immunocompromised individuals (keratitis, meningitis, encephalitis, and disseminated infections) [2,3]. Viral infections are the most common cause of sporadic life-threatening encephalitis in the United States, and up to 75% of these cases are caused by HSV-1 [3,4].

Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs by virus penetration at mucosal surfaces or through skin abrasions. From here, HSV-1 infects innervating sensory nerves of the trigeminal or dorsal root ganglia, where it establishes a life-long latent infection with a high rate of periodical reactivation [2,5,6,7]. The current predominant antiherpetic agents are viral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extension inhibitors, such as acyclovir (ACV), penciclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir. However, these drugs only act to shorten the duration of initial and recurrent episodes to a limited degree [8,9,10]. Consequently, HSV-1 infection is usually described as an incurable disease [1]. Drug-resistant HSV-1 strains among immunocompromised patients are a growing health concern and have emerged after decades of exposure to a single class of antiherpetics compounds [11,12,13]. All these issues support the search for new antiviral compounds that target other stages of HSV-1 infection, such as viral attachment and entry.

Among the 12 surface glycoproteins of HSV, glycoprotein D (gD) plays a key role in the viral attachment and entry process [14,15]. Binding of gD to one of its cellular receptors, nectin-1 or herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), induces a conformational change in the structure of gD, which triggers a cascade of molecular interactions, resulting in the formation of a fusion complex involving gH/gL and gB [15,16,17]. Although some steps of the entry process of HSV-1 remain unclear, the critical role of gD in viral binding and entry, as well as its three-dimensional structure in bound and unbound states, has been well-documented [15,17,18,19]. This provides an opportunity to exploit this knowledge using advanced computational approaches to discover novel antiviral compounds that interact with gD.

Naturally derived molecules have been recognized as highly promising sources of novel antiherpetic compounds. The first antiviral drug, Ara-A, was originally derived from the marine compounds: spongonucleosides, spongothymidine, and spongouridine [20]. Subsequently, a broad range of natural compounds have since been found to possess antiviral activities, with half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) ranging from 10 to 200 µM. These include emodin (EC50 = 21.5 − 195 µM) [21,22,23], epigallocatechin gallate (EC50 = 12.5 − 50 µM) [24,25,26,27], curcumin (EC50 = 89.6 µM) [28,29,30], and other extracted polyphenol compounds [31]. However, practical screening of bioactive molecules with desirable activity from the large pool of diverse natural compounds can be a costly and time-consuming task. Computational modelling represents an underutilized and efficient alternative to accelerate this complex process. Molecular docking is a well-developed tool for screening promising candidates from libraries of bioactive molecules and has been applied to identify inhibitors of viral targets, including thymidine kinase [29,32,33,34], DNA polymerase [35,36], and protease [37]. However, few molecular docking studies have been attempted with a limited focus on natural compounds and viral surface glycoproteins as the target, suggesting a potential research gap [38,39].

Herein, we present a discovery pipeline to identify novel HSV-1 inhibitors from an extensive natural compound library via virtual screening. Molecular docking was targeted at the HVEM and nectin-1 binding sites of the viral gD to identify compounds that bind the virus and prevent infection with different mechanisms of action than those of current antivirals. The antiviral activity of top-ranked molecules was then investigated using in vitro HSV-1 assays. One natural molecule exhibited antiherpetic activity and could serve as a basis for further drug modification and optimization. These findings highlight the capacity of applying computer-aided techniques to facilitate the discovery of lead active compounds (ACs) with desirable properties.

2. Results

2.1. Virtual Screening in Search of Potential gD Inhibitors

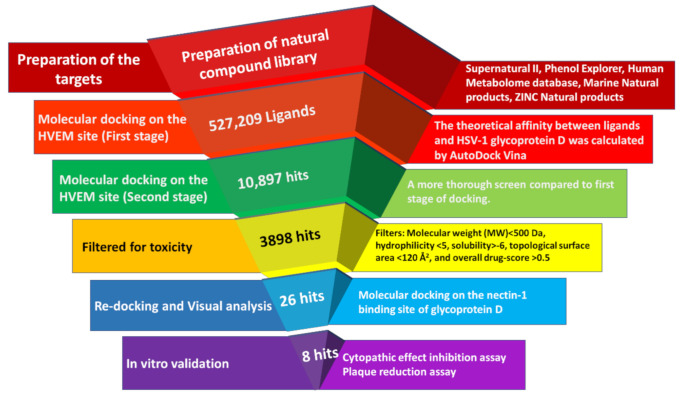

The interaction between gD and its two major cellular receptors, nectin-1 and HVEM, can be described as non-reciprocal competitive binding. Glycoprotein D forms a hairpin structure after interacting with HVEM, which masks the binding site for nectin-1 [16,40]. Similarly, the interaction between gD and nectin-1 blocks the HVEM binding sites [16]. As distinct residues interact with each receptor, we performed targeted molecular docking on each site separately. Docking against the HVEM binding site of gD was conducted first, before a refined set of compounds was docked against the nectin-1 binding site. A schematic diagram of the virtual screening steps and outcomes is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the molecular docking workflow for identifying natural glycoprotein D inhibitors with antiviral activity against HSV-1.

AutoDock Vina software was used to estimate the theoretical affinity between the HVEM binding site of gD and a library of 527,209 natural compounds. The generated docking score is based on the change in Gibbs free energy between bound and unbound states; therefore, a more negative score indicates higher putative affinity [41]. A secondary round of screening, which involved performing a greater number of docking runs, was conducted on the top 2% of compounds (n = 10,897). These compounds included 6654 molecules from the Supernatural II database, 3813 from ZINC Natural Products, 210 from Human Metabolome, 206 from Marine Natural Products, and 14 molecules from Phenol Explorer. The docking scores from this screen ranged from −10.6 to −4.3.

To select ACs for downstream in vitro testing, ligands with docking scores ≤−8.2 were filtered for favorable ADMET properties and commercial availability (n = 3898). The selection criteria were based on toxicity ratings and drug-conforming behavior according to the OSIRIS property explorer tool [42]. Consequently, 26 drug-like compounds that could be readily obtained from commercial vendors were selected for further molecular docking analysis against the nectin-1 binding site.

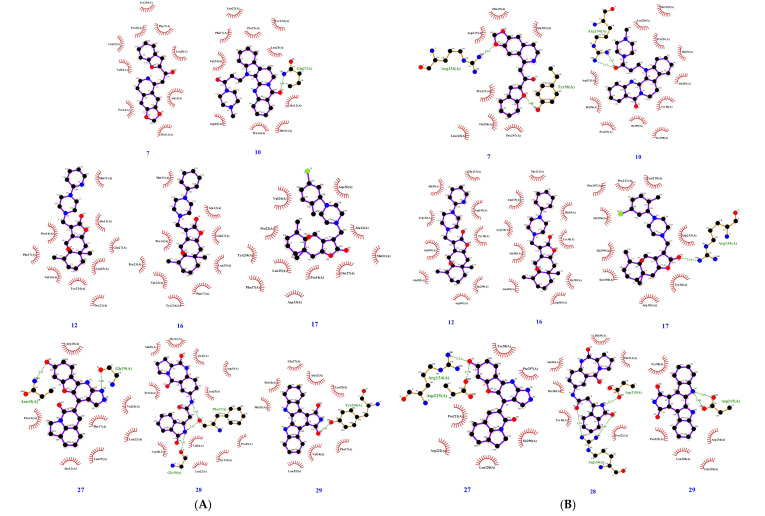

To investigate inhibitory cross-reactivity against the nectin-1 binding site of gD, re-docking analysis was performed with the 26 previously selected compounds. Free energy scores from this redocking screen ranged from −9.4 to −6.8. Docked binding conformations were analyzed by visual inspection, and the top eight ACs with scores ≤−7.6 were selected for in vitro validation. The molecular docking results of the eight selected compounds are listed in Table 1, and their molecular structures are illustrated in Figure 2. The predicted interactions between these eight ligands and the HVEM and nectin-1 binding interfaces of gD are illustrated and outlined in Figure 3 and Table 2. For these eight ligands, the number of predicted interacting residues ranged from 9 to 13 and from 6 to 12 for the HVEM and nectin-1 binding interfaces, respectively. The number of H-bonds ranged from 0 to 3 for both binding interfaces.

Table 1.

List of compounds selected for in vitro validation based on in silico predictions on the (herpes virus entry mediator) HVEM and nectin-1 binding interfaces of glycoprotein D.

| ID | Database ID | Name | Empirical Formular |

Molecular Weight |

Docking Score on | Drug Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVEM Site |

Nectin-1 Site |

||||||

| 7 | Sn00074072 | 1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-2-[(5Z)-2H,6H,7H,8H-[1,3]dioxolo [4,5-g]isoquinoline-5-ylidene]ethenone | C20H15NO4 | 333.34 | −8.2 | −8.6 | 0.58 |

| 10 | Sn00115356 | 13-[3-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-3-oxopropyl]-8,13-dihydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4] pyrido [2,1-b]quinazolin-5(7H)-one | C26H27N5O2 | 441.53 | −8.2 | −8.5 | 0.69 |

| 12 | Sn00099520 | (2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar)-2,5a-dimethyl-9-((4-(isoquino-2-yl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)octahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one | C24H33N3O3 | 411.54 | −8.5 | −7.6 | 0.77 |

| 16 | Sn00104387 | (1Ar,2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar,9Bs)-2,5a-dimethyl-9-((4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)octahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one | C25H34N2O3 | 410.56 | −8.3 | −7.6 | 0.74 |

| 17 | Sn00104404 | (1Ar,2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar,9Bs)-9-( (4-( 5-chloro-2-methylphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)-2,5a-dimethyloctahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one | C26H35ClN2O3 | 459.03 | −8.4 | −7.9 | 0.58 |

| 27 | Zinc96221711 | 5-(7-Hydroxy-1H-benzofuro[3,2-b]pyrazolo[4,3-e]isoquino-4-yl)-1H-pyrrolo[3,2,1-ij]isoquinol-4(2H)-one | C23H14N4O3 | 394.39 | −9.3 | −9.4 | 0.53 |

| 28 | Zinc96115494 | N-((S)-5,11-dioxo-2,3,5,10,11,11a-hexahydro-1H-benzo[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazepin-7-yl)-2-(3-oxoisoindolin-1-yl)acetamide | C22H20N4O4 | 404.43 | −9.5 | −8.6 | 0.76 |

| 29 | Sn00346605 | Arcyriaflavin A | C20H11N3O2 | 325.3 | −9.1 | −9.1 | 0.89 |

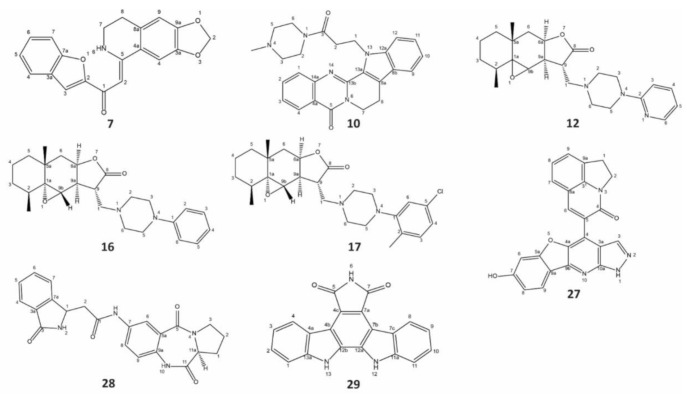

Figure 2.

Structure of the eight natural compounds selected as potential glycoprotein D inhibitors by molecular docking. All eight compounds were subjected to in vitro validation. Listed active compounds (ACs) are: #7,1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-2-[(5Z)-2H,6H,7H,8H-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]5soquinoline-5-ylidene]ethenone; #10,13-[3-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-3-oxopropyl]-8,13-dihydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazolin-5(7H)-one; #12,(2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar)-2,5a-dimethyl-9-((4-(5soquino-2-yl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)octahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one; #16,(1Ar,2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar,9Bs)-2,5a-dimethyl-9-((4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)octahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one; #17, (1Ar,2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar,9Bs)-9-((4-(5-chloro-2-methylphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)-2,5a-dimethyloctahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one,#27,5-(7-Hydroxy-1H-benzofuro[3,2-b]pyrazolo[4,3-e]5soquino-4-yl)-1H-pyrrolo[3,2,1-ij]5soquinol-4(2H)-one; #28, N-((S)-5,11-dioxo-2,3,5,10,11,11a-hexahydro-1H-benzo[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazepin-7-yl)-2-(3-oxoisoindolin-1-yl)acetamide, #29, Arcyriaflavin A. Their molecular structures were illustrated using ChemDraw 18.2 (PerkinElmer).

Figure 3.

Binding interaction diagrams of the eight compounds selected for in vitro validation with the (herpes virus entry mediator) HVEM (A) and nectin-1 (B) binding interfaces of HSV-1 glycoprotein D as predicted by molecular docking. Red lines represent hydrophobic contacts, and broken green lines represent hydrogen bonds, with distances in angstroms.

Table 2.

Predicted interactions between (herpes virus entry mediator) HVEM and nectin-1 binding interfaces of glycoprotein D and compounds selected for in vitro validation.

| ID | HVEM Binding Interface | Nectin-1 Binding Interface | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Interacting Residues |

No. of H-bonds |

Interacting Residues |

No. of Interacting Residues |

No. of H-bonds |

Interacting Residues |

|

| 7 | 9 | 0 | M11, A12, P14, F17, L22, P23, V24, L25, Y234 | 9 | 2 | Y38, H39, R134, D215, L220, P221, I296, P297, A303 |

| 10 | 11 | 1 | M11, A12, P14, F17, L22, P23, V24, L25, D26, Q27, Y234 | 12 | 2 | Y38, H39, R134, D215, M219, L220, P221, I296, P297, S298, I299, A303 |

| 12 | 9 | 0 | M11, A12, P14, F17, P23, V24, L25, Q27, Y234 | 9 | 0 | Y38, H39, R134, T213, D215, I299, D301, A302, A303 |

| 16 | 9 | 0 | M11, A12, P14, F17, P23, V24, L25, Q27, Y234 | 9 | 0 | Y38, H39, R134, T213, D215, I299, D301, A302, A303 |

| 17 | 11 | 0 | M11, A12, D13, P14, F17, P23, V24, L25, D26, Q27, Y234 | 10 | 1 | Y38, R134, D215, L220, P221, I296, P297, S298, I299, A303 |

| 27 | 9 | 2 | A12, P14, N15, F17, R18, G19, L22, V24, L25 | 8 | 2 | Y38, R134, D215, L220, P221, R222, I296, P297 |

| 28 | 13 | 3 | M11, A12, D13, P14, F17, R18, G19, L22, P23, V24, L25, Q27, Y234 | 8 | 3 | Y38, H39, R134, T213, D215, P221, A303, T304 |

| 29 | 9 | 1 | M11, A12, P14, F17, L22, V24, L25, Q27, Y234 | 6 | 2 | Y38, R134, D215, G218, L220, P221 |

2.2. Investigating the Antiviral Activity of Selected Compounds by In Vitro Assays

2.2.1. Determination of Cytotoxicity of ACs

Eight ACs, selected based on their docking scores against both the HVEM and nectin-1 binding interfaces, ADMET profiles, and commercial availability, were investigated for cytotoxicity in African green monkey kidney cell line (VERO). Data from cytotoxicity assays were used to determine test concentrations to be used in cytopathic effect (CPE) inhibition assays, as summarized in Table 3. Three compounds demonstrated negligible toxicity at the highest concentration tested (100 µg/mL) compared with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control: #7, 1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-2-[(5Z)-2H,6H,7H,8H-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]isoquinoline-5-ylidene]ethenone; #27, 5-(7-Hydroxy-1H-benzofuro[3,2-b]pyrazolo[4,3-e]isoquino-4-yl)-1H-pyrrolo[3,2,1-ij]isoquinol-4(2H)-one; and #28, N-((S)-5,11-dioxo-2,3,5,10,11,11a-hexahydro-1H-benzo[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazepin-7-yl)-2-(3-oxoisoindolin-1-yl)acetamide. These compounds were subsequently tested at 10 µg/mL in downstream CPE assays.

Table 3.

Cell viability of tested antiherpes active compounds with African green monkey kidney cell line (VERO).

| ID | Highest Concentration with Cell Viability above 75% | Relative Cell Viability * |

Test Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | >100 µg/mL | 123.7% ± 4.8% | 10 µg/mL |

| 10 | 1 µg/mL | 73.2% ± 5.9% | 1 µg/mL |

| 12 | 1 µg/mL | 77.4% ± 4.2% | 1 µg/mL |

| 16 | 1 µg/mL | 102.1% ± 16.7% | 1 µg/mL |

| 17 | 1 µg/mL | 96.8% ± 7.1% | 1 µg/mL |

| 27 | >100 µg/mL | 105.9% ± 0.2% | 10 µg/mL |

| 28 | >100 µg/mL | 105.0% ± 0.5% | 10 µg/mL |

| 29 | 1 µg/mL | 86.2% ± 14.8% | 1 µg/mL |

* Relative cell viability of ACs is presented as mean ± standard deviation.

The remaining five ACs exhibited toxicity to the cells at a concentration of 10 µg/mL (Table 3): #10, 13-[3-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-3-oxopropyl]-8,13-dihydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazolin-5(7H)-one; #12, (2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar)-2,5a-dimethyl-9-((4-(isoquino-2-yl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)octahydro-2H-oxiren[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one; #16, (1Ar,2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar,9Bs)-2,5a-dimethyl-9-((4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)octahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one; #17, (1Ar,2S,5Ar,6Ar,9S,9Ar,9Bs)-9-((4-(5-chloro-2-methylphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)-2,5a-dimethyloctahydro-2H-oxireno[2′,3′:4,4a]naphtho[2,3-b]furan-8(9Bh)-one; and #29, Arcyriaflavin A. Therefore, these five compounds were tested at a concentration of 1 µg/mL in downstream CPE assays.

2.2.2. Investigating the Mechanism of Action of ACs by Time of Addition Assay

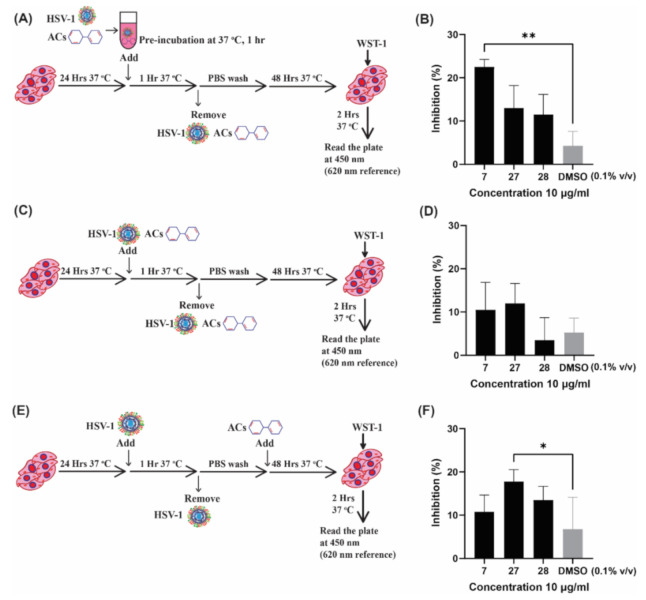

Next, the eight ACs were assessed in cell-based assays to test for antiviral activity against HSV-1. Three separate assays were performed to elucidate the mechanism of action (Figure 4A,C,E). A viral inactivation assay was performed by incubating HSV-1 with ACs at 10 µg/mL or 1 µg/mL (depending on cytotoxicity) before addition to the cells. Viral attachment and entry-inhibition assay involved the simultaneous addition of virus and ACs to cells (Figure 4C), whereas post-entry effects of ACs were investigated by adding ACs 1 h post-HSV-1 infection (Figure 4E). The initial screening was performed using a low MOI of 0.01 (Supplementary Materials Figure S1). Three promising ACs, #7, #27, and #28, were selected based on cytotoxicity (Table 3) and preliminary results (Figure S1) and further tested at MOI of 5, which triggered a cytopathic effect in 90% of cultured cells. The inhibitory effect of each compound was measured by cell survival as determined by using water-soluble tetrazolium 1 (WST-1) reagent (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Antiviral screening assays for three selected active compounds. The antiviral activity of active compounds (ACs) was investigated at three different stages. The antiviral activity of ACs #7, #27, and #28 was tested at 10 µg/mL. (A) Schematic diagram of the viral inactivation assay performed by preincubating Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 (HSV-1) with ACs for 1 h prior to addition to cells is. (B) Results of the viral inactivation assay. Viral attachment and entry inhibition of ACs were investigated by simultaneously adding the virus and ACs to cells, as shown in (C); results are shown in (D). The post-entry antiviral effect of ACs was tested by adding ACs after infection (E); results are plotted in (F). Cells infected with the virus and treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 0.1% v/v were included as solvent controls. This experiment was performed four times with triplicates. Means of the four experiments are plotted with standard error of the mean. Friedman test, followed by Dunn’s test, was used to determine statistical significance (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Two out of eight tested compounds demonstrated promising antiviral activity at different stages of infection. AC#7 exhibited significantly higher activity than the DMSO control at the viral inactivation stage, as shown in Figure 4B. AC#27 was also found to possess antiherpetic activity; however, this effect was seen at the post-entry stage (Figure 4F), indicating inhibition at later stages of the viral infection. The antiviral activity of AC#7 was found to be most effective when added to the virus prior to addition to the cells. No antiviral activity was observed when cells were preincubated with AC#7 (at 10 µg/mL) prior to HSV-1 infection (Figure S2). Based on the obtained data, the activity exhibited by AC#7 reflects the hypothesized mechanism of action predicted by the molecular docking study. Therefore, AC#7 was selected for further testing using a dose–response assay.

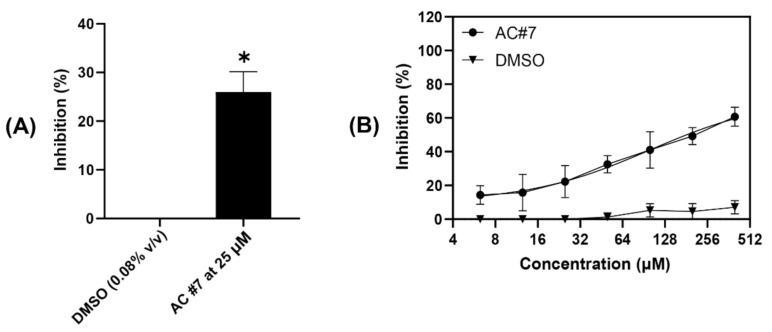

2.2.3. Estimating the Efficacy of ACs by Plaque Reduction Assay

To visualize and evaluate the activity of AC#7, a plaque reduction assay was performed at concentrations from 400 µM (133.33 µg/mL) to 6.25 µM (2 µg/mL) using two-fold serial dilutions. Cells treated with DMSO only at concentrations ranging from 1.33% (v/v) to 0.02% (v/v) were used as a solvent control, and the results are plotted in Figure 5. AC#7 significantly reduced the number of virus-induced plaques compared to the DMSO control at a concentration of 25 µM (Figure 5A). This is consistent with the results obtained from the CPE assay, in which the AC was tested at a concentration of 30 µM (10 µg/mL) (Figure 4B). Notably, AC#7 demonstrated a dose-dependent antiviral response when pre-incubated with the virus compared to the DMSO control (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Quantification of the antiviral activity of AC #7. The antiviral activity of AC#7 was investigated by plaque reduction assay in African green monkey kidney cell line (VERO). (A) AC#7 demonstrated significantly high antiviral activity at a concentration of 25 µM compared to the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control (0.08% v/v). (B) AC#7 exhibited antiviral activity in a dose-dependent manner compared with the DMSO controls. The DMSO controls were tested at concentrations of 1.33%, 0.67%, 0.33%, 0.16%, 0.08%, 0.04%, and 0.02% (v/v), which are the concentrations at which AC#7 was dissolved in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) media. The plaque reduction assay was performed three times with duplicates. Means of the three experiments are plotted with standard error of the mean. One-sample t-test was applied to compare the antiviral activity of the DMSO control and AC#7 (* p < 0.05).

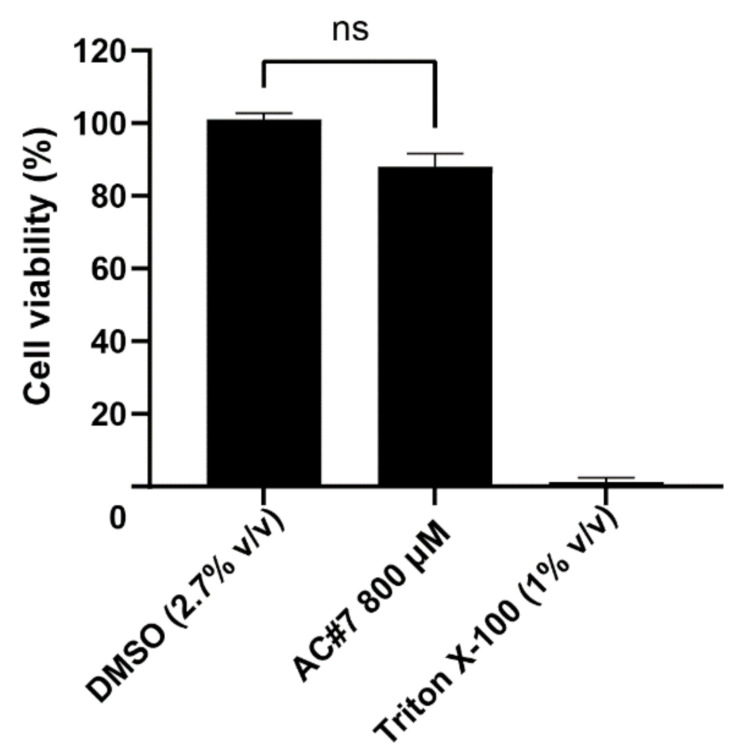

The EC50 value of AC#7 was 183 µM (61 µg/mL), as calculated based on the asymmetric nonlinear regression model (R2 = 0.84). To determine the therapeutic index (TI), the cytotoxicity of AC#7 was further tested at a concentration of 800 µM. Cell viability was measured 46 h after the 2 h of exposure to AC#7. Negligible toxicity to VERO cells was found, as illustrated in Figure 6. Thus, the TI of AC#7 is estimated to be >4.37, which suggests this molecule could serve as a potential lead compound for future antiviral drug development [43,44].

Figure 6.

Toxicity of AC#7 in VERO cells at 800 µM. The cytotoxicity of AC#7 was tested by incubating Vero cells with AC#7 (800 µM) for 2 h. AC#7 was then removed, and cells were incubated in fresh media for a further 46 h before cell viability was evaluated using water-soluble tetrazolium 1. Cells without any treatment were included as cell-only control and used to calculate cell viability. Cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (2.7% v/v), corresponding to the solvent concentration in the tested samples, were used as the solvent control. The wells treated with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 were used as a negative control. The cytotoxicity assay was performed three times with duplicates. Means of the three experiments are plotted with standard error of the mean. Wilcoxon test was applied to compare the cytotoxicity of DMSO control and AC#7 (ns indicates not significant, p > 0.05).

For comparison, the standard antiherpetic drug ACV was tested in parallel to AC#7. ACV was added post-HSV infection due to its inhibitory mechanism at the viral DNA replication stage (Figure S3). The EC50 of ACV was 0.77 µM, determined using the same asymmetric nonlinear regression model (R2 > 0.99). This is consistent with previously published in vitro results obtained with VERO cells in which the calculated EC50 for ACV lies between 0.3 and 4.3 µM [45,46].

3. Discussion

The basis of this study lies in the well-understood interactions between HSV-1 envelope glycoprotein D and its cellular receptors [18,19]. The wild-type strains of HSV-1 exploit either nectin-1 or HVEM as entry receptors to infect host cells, depending on the cell type [47,48]. For key target cells, neurons and human keratinocytes, nectin-1 has been reported as the primary receptor and is therefore the most important. Alternatively, HVEM functions as the main receptor in nectin-1-deficient cell lines, with similar infectivity [47,48,49]. Thus, it may be important for antiviral compounds to inhibit both nectin-1 and HVEM binding sites on gD to be considered potential therapeutic agents. The interaction between HVEM and gD forms an N-terminal hairpin structure that masks the nectin-1 binding site, whereas the binding between nectin-1 and gD blocks the accessibility of the HVEM [16]. Therefore, molecular docking must be performed on multiple regions of the glycoprotein, a requirement that entails significant computational resources to screen the large compound library of over 500,000 molecules used in this study. To overcome this obstacle, an innovative docking strategy was applied, resulting in the selection of eight compounds with predicted affinity to both binding sites in silico.

Among the eight chosen molecules, AC#7, [1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-2-[(5Z)-2H,6H,7H,8H-[1,3] dioxolo[4,5-g] isoquinolinelin-5-ylidene]ethenone] was identified as a weak HSV-1 inhibitor. The Gibbs free energy values generated by the docking software for AC#7 on both sites were −8.2 kcal/M and −8.6 kcal/M for the HVEM and nectin-1 sites, respectively. However, affinity with gD is not necessarily correlated with the potency of antiviral activity. A number of aptamers that have been reported to demonstrate strong affinity with gD at nanomolar concentrations using surface plasmon resonance were found to possess insignificant antiviral activity in vitro [50]. Therefore, some highly ranked hits, such as AC#28 and #29, may still bind gD, although they failed to show antiherpetic activity in the in vitro assays.

Two weak antiviral ligands were identified in this study; however, only AC#7 demonstrated activity at the early stage of infection, aligning with the in silico results. AC#7 is predicted to interact with nine residues in the HVEM binding interface via hydrophobic contacts and nine residues in the nectin-1 binding interface via hydrophobic contacts and two hydrogen bonds. Notably, the interaction at the nectin-1 interface involves amino acid residue Y38, which has been identified as critical for viral entry via the nectin-1 receptor [51,52,53]. Additionally, there are no overlapping residues between the binding interfaces, suggesting that the compound can bind to both sites simultaneously. However, although AC#7 exhibited low antiviral activity in the early stage of infection, further tests are required to confirm the interaction between this compound and glycoprotein D. Techniques such as surface plasmon resonance could provide deeper insights into the mechanism of action at a molecular level and could guide chemical modifications to improve the antiviral efficacy of this compound.

The compound 9-((2-Hydroxyethoxy) methyl) guanine, commonly known as ACV, is the gold standard in the treatment of HSV-1 infection, with an EC50 of around 1 µM in vitro [54]. ACV is a typical nucleoside analogue that acts after viral entry, requiring phosphorylation by virally encoded thymidine kinase to prevent viral DNA elongation, resulting in a shorter duration of infection and relief from symptoms [10,55]. Other antiherpetic drugs, including nucleosides, nucleotides, and pyrophosphate analogues, all target viral replication and hence fail to eliminate the lifelong latent infection caused by HSV-1 [10]. Docosanol is the only approved herpesvirus entry inhibitor and directly interferes with the host-cell surface phospholipids [56]. However, drugs targeting host cells may lead to higher toxicity and lower selectivity compared to compounds that interact specifically with viral components [10,57]. Compared to these drugs, AC#7 demonstrated a distinct mechanism, reducing HSV-1 infection at an early stage. This unique activity of AC#7 can be used to exploit this molecule as the basic structure for future drug modification.

Although AC#7 acts at the early stage of infection with an acceptable selectivity (therapeutical index >4) [44], its low antiviral activity remains the main drawback for its consideration as a potential antiviral agent. This may be explained by several reasons. Firstly, it has proven challenging for small molecular compounds to inhibit high-affinity interactions between proteins with contributions from either continuous or discontinuous sites in their respective protein structures [58,59,60]. Another explanation is the potential interaction between these ligands and other viral or cellular components. Given that molecular docking does not account for the complex environment of in vitro conditions, unknown off-target effects are a limitation of virtual screening [61].

Discovery of structures with low activity can lead to the identification of potent compounds via medicinal chemistry approaches. As an example, the HSV-1 ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor BILD 1633 SE demonstrated higher antiviral activity than ACV in vitro and exhibited a potent therapeutic effect against ACV-resistant HSV-1 infections in vivo [62]. This antiherpetic agent was designed via extensive drug modification and optimization of a series of peptides with initial EC50 values between 30 and 780 µM in vitro [63,64,65]. The drug improvement process of BILD1633 SE demonstrates the feasibility of improving the potency of molecules via medicinal chemistry approaches [62,63,64,65]. More recently, a chemical-modification design strategy targeting the cysteine-3-like protease (3CLpro) enzyme of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), has given rise to the novel antiviral PF-00835231, the main component of Paxlovid [66]. A previously identified inhibitor of human rhinovirus (rupintrivir) was used as the basis of the study; however, the drug and other modified versions produced weak to undetectable inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro. Consequently, structural binding data from co-crystallography experiments were used to guide chemical modifications, resulting in the production of PF-00835231. Although initially intended for SARS-CoV, this compound demonstrates promising activity against SARS-CoV-2 and is currently being studied in clinical trials [67]. Based on these examples, a similar pathway could be applied to AC#7 to engineer superior antiherpetic compounds.

Natural compounds are an important resource for modern drug development. More than 100 small molecules with diverse antiherpetic activities have been identified from a wide range of organisms [8,43,68,69]. AC#7 was originally derived from glycyrrhiza glabra, which has been found to have versatile bioactivity, including antiviral activity [70,71,72,73]. This molecule contains benzofuran and isoquinoline elements (Figure 2), which have both been found to possess antiviral abilities [74,75,76]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of antiherpetic activity of a molecule with both benzofuran and isoquinoline elements in vitro, suggesting a promising foundation for designing a new generation of antiviral drugs via medicinal chemistry.

The fact that AC#7 reduced HSV-1 at the early stage of infection in a dose-dependent manner shows that this compound likely acts on the viral surface glycoprotein, gD, as predicted by the molecular docking analysis. Identification of a new natural molecule with an antiviral mode of action different from that of ACV provides a fresh basis for subsequent drug development and optimization.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. In Silico Screening

4.1.1. Preparation of Natural Compound Library

A total of 527,209 compounds from five natural compound libraries (SuperNatural II [77], Phenol Explorer [78], Human Metabolome Database [79], Marine Natural Products [80], and ZINC Natural Products [81]) were downloaded in SDF format from the Miguel Hernandez University Molecular Docking site [82]. To prepare ligands for docking, each compound was edited with PyMOL to include polar hydrogens [83]. For the initial round of virtual screening, 3D coordinates were generated by converting files to MOL2 format with Marvin Suite 6.0 from ChemAxon [84]. Ligands were then energy-minimized using the universal force field (UFF) and converted to PDBQT format with Open Babel software v 3.1.1[85]. For the second round of screening, ligands were energy-minimized and converted from SDF to PDBQT format using the PyRx virtual screening tool [86].

4.1.2. Preparation of Receptor Proteins

Glycoprotein D, the key surface protein of HSV-1 involved in viral attachment to host cells, was selected for molecular docking. The X-ray-derived crystal structures for gD complexed with HVEM (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 1JMA) and in unliganded form (PDB ID: 2C36) were downloaded from the RCSB protein databank [18]. To prepare receptors for screening, files were edited using PyMOL to add polar hydrogens and to remove water molecules, ions, and ligands [83]. PDB files were converted to PDBQT format using the PyRx virtual screening tool [86].

4.1.3. Virtual Screening on the HVEM Binding Site of gD

Virtual screening was performed using AutoDock Vina molecular docking software [41]. A targeted docking approach was employed by defining a search space containing residues involved in the interaction with the native HVEM receptor [18]. The crystal structure of gD bound to HVEM (1JMA) was used as the docking model, and the search space was defined as follows: center: coordinates (x,y,z): −27.284, 50.152, −6.099; dimensions (x,y,z): 15.364, 23.087, 22.147. A flexible docking procedure was adopted to account for changes in the receptor conformation. The gD residues defined as flexible were: C15, R24, V25, E27, A28, and C29.

To identify optimal docking conformations whilst minimizing the number of computational resources required, the protocol was conducted in two stages. The initial round of screening was performed with all 527,209 ligands. For each ligand, the number of docked conformations (modes) was set to 10, and the number of runs (exhaustiveness) was set to 20. A secondary, more thorough screen was then conducted with the top 10,000 ligands, with the number of runs increased to 80. As some ligands produced identical docking scores, the number of compounds screened in this round was 10,897.

4.1.4. ADMET Analysis

To filter for compounds with favorable absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties, ligands ranked within the top 25 scores from the secondary screen were assessed (n = 3893). The OSIRIS property explorer was used to compare the properties of each ligand to currently traded drugs and predict their toxicity based on data from the Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances (RTECS) database [42]. Ligands were filtered for the absence of toxic fragments (mutagenic, tumorigenic, irritant, or reproductive effects), molecular weight (MW) < 500 Da, hydrophilicity (cLogP) < 5, solubility (logS) >−6, topological surface area (TPSA) < 120Å2, drug likeness > 0, and overall drug score >0.5.

4.1.5. Redocking Selected Compounds on the Nectin-1 Binding Site of gD

As nectin-1 is a primary receptor of gD and occupies a binding site distinct from that of HVEM, the ligands ranked with the top 25 scores, filtered for favorable ADMET profiles and commercial availability, were redocked against the nectin-1 binding site of gD (n = 26). For this docking experiment, an unliganded X-ray-derived crystal structure of gD was used due to its high resolution of 2.11Å (PDB ID: 2C36) [19]. The search space was selected based on a region of interacting residues at the nectin-1 binding interface known as surface patch 2 [87]. The following residues were defined as flexible: V37, Y38, H39, Q132, V214, D215, I217, M219, L220, R222, and F223. The search space was defined as follows: center coordinates (x,y,z): 60.637, 42.391, 98.991; dimensions (x,y,z): 20.428, 24.261, 15.139. As with the virtual screen against the HVEM binding site, the number of docked conformations was set to 10, and the number of runs was set to 80.

The docking results were visualized using PyMOL. Residues involved in hydrogen-bonding and hydrophobic interactions were plotted using LigPlot+ software [88].

4.2. In Vitro Validation

4.2.1. Chemicals

A total of 8 synthetic purified ACs with docking scores ≤−8.2 for the HVEM site and ≤−7.6 for the nectin-1 site and favorable ADMET properties were selected for in vitro screening. All ACs were purchased from VITAS-M laboratory, USA, as listed in Table 1. Their molecular structures are illustrated by ChemDraw 18.2 (PerkinElmer). Each compound was dissolved in molecular-grade dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma, Melbourne, Australia) to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL and kept at −20 °C until use.

4.2.2. Cells and Virus

HSV-1 strain F was used in all antiviral assays in this study. African green monkey epithelial kidney (VERO) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Lonza, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% (v/v) penicillin streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Scoresby, VIC, Australia) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. HSV-1 was propagated in VERO cells and titrated by plaque assay as described in [8]. Viral stocks were aliquoted and kept at −80 °C until use.

4.2.3. Cytotoxicity of ACs

The cytotoxicity of each AC was determined using WST-1 reagent (Sigma, Australia) as described previously [43]. VERO cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Then, the ACs were 10-fold serially diluted in DMEM supplemented with 2% (v/v) FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin streptomycin to concentrations of 100 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 0.1 µg/mL and incubated with the cells for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, cells were washed with DMEM with 2% FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin streptomycin once and incubated with 10% (v/v) WST-1 for 2 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. To determine cell viability, plates were read by a SpectraMAX iD3 plate reader (Molecular Devices) at 450 nm. The absorbance at 620 nm was used as a reference. Cells treated with DMSO only were included as solvent controls, and untreated cells were included as cell-only control. Wells containing DMEM without cells were prepared as blanks. The cytotoxicity of each AC was calculated by comparing treated cells with the DMSO control Equation (1). The experiment was performed in quadruplicate.

| (1) |

4.2.4. Time of Addition Assay

A cytopathic effect (CPE) inhibition assay was applied to screen for the antiviral activity of selected ACs at different time points. VERO cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well for 24 h before the addition of virus at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The initial screening was conducted at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 0.01; then, the active compounds were tested with a higher MO1 = 5 to confirm their activity. ACs were tested at 10 µg/mL or 1 µg/mL depending on their cytotoxicity.

To identify compounds with antiviral activity, virus and ACs were added at different time points: viral inactivation (preincubation of the virus with ACs for 1 h prior to addition to cells at 37 °C under 5% CO2), attachment and entry (ACs and virus were added to cells simultaneously), and post-entry stages (ACs were added 1 h after HSV-1 infection of cells and were kept during the entire 48 h incubation at 37 °C under 5% CO2). After infection, the cells were incubated for another 48 h in DMEM with 2% FBS before addition of WST-1 to quantify cell viability. Three controls were included: Solvent controls were prepared by diluting DMSO at concentration of 0.1% (v/v) in DMEM without ACs and added to the cells at different time points corresponding to the samples. Cells cultured with DMEM only were prepared as the cell control, and cells infected with virus without DMSO were included as the virus control. The initial antiviral activity of each AC was calculated using Equation (2) as described in [89], with modifications. The initial screening (with MOI = 0.01) was performed once in quadruplicate, and the secondary experiments (with MOI = 5) were conducted four times in triplicate. The ACs that demonstrated CPE inhibition were further analyzed by plaque reduction assay.

| (2) |

4.2.5. Plaque Reduction Dose–Response Assay

The antiviral activity of selected ACs on VERO cells was quantitatively determined by plaque reduction assay as described in [43], with modifications. VERO cells were seeded in 24-well plates (50,000 cells/well) for 24 h. The virus was diluted to 50 plaque-forming units (PFU) per 0.2 mL and preincubated with the ACs at different concentrations (400, 200, 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.25 µM) or DMSO controls (1.33%, 0.67%, 0.33%, 0.16%, 0.08%, 0.04%, and 0.02%, v/v) for 1 h before being added to the cell monolayer. Then, the cells were incubated with the mixture for 1 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. After removing the inoculum, the cells were rinsed with PBS and overlayed with DMEM containing 1.6% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and 1% FBS. After incubation for 48 h, the cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma, Australia). The number of plaques was counted manually using upright microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo Japan). Cells infected with virus without DMSO were included as the virus control. The antiviral activity was calculate using Equation (3) [90], and the EC50 values were determined by linear regression analysis of the dose–response curve.

| (3) |

4.2.6. Toxicity of AC#7 on VERO Cells at High Concentrations

Since AC#7 did not exhibit cytotoxicity to VERO cells in the plaque reduction assay at a concentration of 400 µM, its toxicity was further tested at 800 µM in 96 well-plates. Due to stock limitation, 800 µM was the highest concentration that could be tested. Briefly, VERO cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Then, the cells were exposed to AC#7 at a concentration of 800 µM or controls for 2 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. AC#7 or controls were then removed and replaced with fresh DMEM with 2% FBS and 1% penicillin streptomycin. Cells were incubated for 46 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. After incubation, cells were washed with DMEM once and incubated with 10% (v/v) WST-1 for 2 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells treated with DMSO at 2.7% (v/v), corresponding to the solvent used to dissolve 800 µM AC#7 in DMEM, were included as solvent control. Cells treated with Triton X-100 at 1% (v/v) (Sigma, Australia) were included as negative control, and untreated cells were included as cell-only controls. Then, the cell viability of AC#7 was calculated using Equation (1). Wells containing DMEM without cells were prepared as blanks. The experiment was performed three times with duplicates.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Linear regression curves were obtained using the five-parameter logistic sigmoidal model offered by the same software. Significance testing between multiple samples and controls was performed using Friedman test followed by a post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Wilcoxon matched test or t-tests were applied to compare the mean between two samples.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first application of a large-scale structure-based virtual screen targeting the binding interfaces of HSV-1 glycoprotein D to identify inhibitors of early viral infection. Two out of eight selected compounds exhibited significant activity against HSV-1 infection in vitro. Notably, compound AC#7 demonstrated a mechanism of action consistent with inhibiting early-stage infection. Although the potency of AC#7 is lower than that of current first-line drugs, these data suggests that it could serve as a structural basis for further drug development. More importantly, this work supports the use of molecular docking as a powerful tool for identifying novel antiviral compounds. Future studies will expand on these computational methods with an aim to screen additional compound libraries, as well as other viral protein targets.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the technical assistance of Nathaniel Butterworth of the Sydney Informatics Hub, a Core Research Facility of the University of Sydney, and for the use of the University of Sydney’s high-performance computing cluster, Artemis. The authors also acknowledge the assistance of the high-performance computing system Gadi from the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which is supported by the Australian Government. The authors thank Kevin Danastas from the Centre for Virus Research, the Westmead Institute for Medical Research, for statistical analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ph15030361/s1, Figure S1: Preliminary screening of antiviral activity of eight select ACs; Figure S2: Investigating the antiviral activity of AC#7 when added to cells before HSV-1 infection; Figure S3: Inhibition of antiviral activity by ACV in the post-entry stage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W., A.S., P.V., F.D. and A.L.C.; methodology, J.W., H.P. and M.M.-S.; software, H.P.; validation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and H.P.; writing—review and editing, A.S., M.M.-S., A.L.C., P.V. and F.D.; visualization, J.W. and H.P.; supervision, F.D. and A.L.C.; project administration, F.D. and A.L.C.; funding acquisition, F.D. and A.L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council and Marine Biotechnology Australia Pty Ltd. from grant LP150100314 (to F.D. and A.L.C.), as well as Jatcorp Pty Ltd. (Toorak, VIC, Australia).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Massive Proportion of World’s Population Are Living with Herpes Infection. 2020. [(accessed on 8 March 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-05-2020-massive-proportion-world-population-living-with-herpes-infection.

- 2.Diefenbach R., Miranda-Saksena M., Douglas M.W., Cunningham A.L. Transport and egress of herpes simplex virus in neurons. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007;18:35–51. doi: 10.1002/rmv.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawada J.-I. Neurological Disorders Associated with Human Alphaherpesviruses. In: Kawaguchi Y., Mori Y., Kimura H., editors. Human Herpesviruses. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2018. pp. 85–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyler K.L. Acute Viral Encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:557–566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1708714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owen D.J., Crump C.M., Graham S.C. Tegument assembly and secondary envelopment of alphaherpesviruses. Viruses. 2015;7:5084–5114. doi: 10.3390/v7092861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mettenleiter T.C., Klupp B.G., Granzow H. Herpesvirus assembly: An update. Virus Res. 2009;143:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanfield B.A., Kousoulas K.G., Fernandez A., Gershburg E. Rational Design of Live-Attenuated Vaccines against Herpes Simplex Viruses. Viruses. 2021;13:1637. doi: 10.3390/v13081637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanjani N.T., Miranda-Saksena M., Valtchev P., Diefenbach R.J., Hueston L., Diefenbach E., Sairi F., Gomes V.G., Cunningham A.L., Dehghani F. Abalone Hemocyanin Blocks the Entry of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 into Cells: A Potential New Antiviral Strategy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:1003–1012. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01738-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Clercq E. Strategies in the design of antiviral drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrd703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadowski L., Upadhyay R., Greeley Z., Margulies B. Current Drugs to Treat Infections with Herpes Simplex Viruses-1 and -2. Viruses. 2021;13:1228. doi: 10.3390/v13071228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin M.J., Bacon T.H., Leary J.J. Resistance of Herpes Simplex Virus Infections to Nucleoside Analogues in HIV-Infected Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;39:S248–S257. doi: 10.1086/422364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topalis D., Gillemot S., Snoeck R., Andrei G. Thymidine kinase and protein kinase in drug-resistant herpesvirtises: Heads of a Lernaean Hydra. Drug Resist. Updates. 2018;37:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van de Sand L., Bormann M., Schmitz Y., Heilingloh C.S., Witzke O., Krawczyk A. Antiviral Active Compounds Derived from Natural Sources against Herpes Simplex Viruses. Viruses. 2021;13:1386. doi: 10.3390/v13071386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenberg R.J., Atanasiu D., Cairns T.M., Gallagher J.R., Krummenacher C., Cohen G.H. Herpes Virus Fusion and Entry: A Story with Many Characters. Viruses. 2012;4:800–832. doi: 10.3390/v4050800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connolly S.A., Jardetzky T.S., Longnecker R. The structural basis of herpesvirus entry. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020;19:110–121. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00448-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazear E., Whitbeck J.C., Zuo Y., Carfí A., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., Krummenacher C. Induction of conformational changes at the N-terminus of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D upon binding to HVEM and nectin-1. Virology. 2013;448:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallbracht M., Backovic M., Klupp B.G., Rey F.A., Mettenleiter T.C. Common characteristics and unique features: A comparison of the fusion machinery of the alphaherpesviruses Pseudorabies virus and Herpes simplex virus. In: Kielian M., Mettenleiter T.C., editors. Advances in Virus Research. 1st ed. Volume 104. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2019. pp. 225–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carfi A., Willis S.H., Whitbeck J., Krummenacher C., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., Wiley D.C. Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein D Bound to the Human Receptor HveA. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:169–179. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krummenacher C., Supekar V.M., Whitbeck J.C., Lazear E., Connolly S.A., Eisenberg R.J., Cohen G.H., Wiley D.C., Carfi A. Structure of unliganded HSV gD reveals a mechanism for receptor-mediated activation of virus entry. EMBO J. 2005;24:4144–4153. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sagar S., Kaur M., Minneman K.P. Antiviral Lead Compounds from Marine Sponges. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:2619–2638. doi: 10.3390/md8102619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiang C.-Y., Ho T.-Y. Emodin is a novel alkaline nuclease inhibitor that suppresses herpes simplex virus type 1 yields in cell cultures. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;155:227–235. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y., Li X., Pan C., Cheng W., Wang X., Yang Z., Zheng L. The intervention mechanism of emodin on TLR3 pathway in the process of central nervous system injury caused by herpes virus infection. Neurol. Res. 2020;43:307–313. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2020.1853989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong H.-R., Luo J., Hou W., Xiao H., Yang Z.-Q. The effect of emodin, an anthraquinone derivative extracted from the roots of Rheum tanguticum, against herpes simplex virus in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;133:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Oliveira A., Adams S.D., Lee L.H., Murray S.R., Hsu S.D., Hammond J.R., Dickinson D., Chen P., Chu T.-C. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 with the modified green tea polyphenol palmitoyl-epigallocatechin gallate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;52:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C.-Y., Yu Z.-Y., Chen Y.-C., Hung S.-L. Effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate and acyclovir on herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in oral epithelial cells. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020;120:2136–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pradhan P., Nguyen M.L. Herpes simplex virus virucidal activity of MST-312 and epigallocatechin gallate. Virus Res. 2018;249:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isaacs C.E., Wen G.Y., Xu W., Jia J.H., Rohan L., Corbo C., Di Maggio V., Jenkins E.C., Hillier S. Epigallocatechin Gallate Inactivates Clinical Isolates of Herpes Simplex Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:962–970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00825-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zandi K., Ramedani E., Mohammadi K., Tajbakhsh S., Deilami I., Rastian Z., Fouladvand M., Yousefi F., Farshadpour F. Evaluation of Antiviral Activities of Curcumin Derivatives against HSV-1 in Vero Cell Line. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010;5:1935–1938. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1000501220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Halim S.M.A., Mamdouh M.A., El-Haddad A.E., Soliman S.M. Fabrication of Anti-HSV-1 Curcumin Stabilized Nanostructured Proniosomal Gel: Molecular Docking Studies on Thymidine Kinase Proteins. Sci. Pharm. 2020;88:9. doi: 10.3390/scipharm88010009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreira V.H., Nazli A., Dizzell S.E., Mueller K., Kaushic C. The Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Curcumin Protects the Genital Mucosal Epithelial Barrier from Disruption and Blocks Replication of HIV-1 and HSV-2. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musarra-Pizzo M., Pennisi R., Ben-Amor I., Smeriglio A., Mandalari G., Sciortino M.T. In Vitro Anti-HSV-1 Activity of Polyphenol-Rich Extracts and Pure Polyphenol Compounds Derived from Pistachios Kernels (Pistacia vera L.) Plants. 2020;9:267. doi: 10.3390/plants9020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pospisil P., Pilger B.D., Marveggio S., Schelling P., Wurth C., Scapozza L., Folkers G., Pongracic M., Mintas M., Malic S.R. Synthesis, Kinetics, and Molecular Docking of Novel 9-(2-Hydroxypropyl)purine Nucleoside Analogs as Ligands of Herpesviral Thymidine Kinases. Helvetica Chim. Acta. 2002;85:3237–3250. doi: 10.1002/1522-2675(200210)85:10<3237::AID-HLCA3237>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krištafor S., Novaković I., Kraljević T.G., Pavelić S.K., Lučin P., Westermaier Y., Pernot L., Scapozza L., Ametamey S.M., Raić-Malić S. A new N-methyl thymine derivative comprising a dihydroxyisobutenyl unit as ligand for thymidine kinase of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1 TK) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:6161–6165. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kant K., Lal U.R., Kumar A., Ghosh M. A merged molecular docking, ADME-T and dynamics approaches towards the genus of Arisaema as herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2018;78:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoneda J., Albuquerque M., Leal K.Z., Santos F.D.C., Batalha P.N., Brozeguini L., Seidl P.R., de Alencastro R.B., Cunha A., de Souza M.C.B.V., et al. Docking of anti-HIV-1 oxoquinoline-acylhydrazone derivatives as potential HSV-1 DNA polymerase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2014;1074:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.05.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan S.T.S., Šudomová M., Berchová-Bímová K., Šmejkal K., Echeverría J. Psoromic Acid, a Lichen-Derived Molecule, Inhibits the Replication of HSV-1 and HSV-2, and Inactivates HSV-1 DNA Polymerase: Shedding Light on Antiherpetic Properties. Molecules. 2019;24:2912. doi: 10.3390/molecules24162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mello J.F.R., Botelho N.C., Souza A.M.T., Oliveira R., Brito M.A., Abrahim-Vieira B.D.A., Sodero A.C.R., Castro H.C., Cabral L.M., Miceli L.A., et al. Computational Studies of Benzoxazinone Derivatives as Antiviral Agents against Herpes Virus Type 1 Protease. Molecules. 2015;20:10689–10704. doi: 10.3390/molecules200610689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siqueira E.M.D.S., Lima T.L.C., Boff L., Lima S.G.M., Lourenço E.M.G., Ferreira É.G., Barbosa E.G., Machado P.R.L., Farias K.J.S., Ferreira L.D.S., et al. Antiviral Potential of Spondias mombin L. Leaves Extract Against Herpes Simplex Virus Type-1 Replication Using In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Planta Med. 2020;86:505–515. doi: 10.1055/a-1135-9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keshavarz M., Shamsizadeh F., Tavakoli A., Baghban N., Khoradmehr A., Kameli A., Rasekh P., Daneshi A., Nabipour I., Vahdat K., et al. Chemical compositions and experimental and computational modeling activity of sea cucumber Holothuria parva ethanolic extract against herpes simplex virus type 1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;141:111936. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petermann P., Rahn E., Thier K., Hsu M.-J., Rixon F.J., Kopp S.J., Knebel-Mörsdorf D. Role of Nectin-1 and Herpesvirus Entry Mediator as Cellular Receptors for Herpes Simplex Virus 1 on Primary Murine Dermal Fibroblasts. J. Virol. 2015;89:9407–9416. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01415-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Organic Chemistry Portal. [(accessed on 10 November 2020)]. Available online: http://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/peo/

- 43.Zanjani N.T., Sairi F., Marshall G., Saksena M.M., Valtchev P., Gomes V.G., Cunningham A., Dehghani F. Formulation of abalone hemocyanin with high antiviral activity and stability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014;53:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyu S.Y., Rhim J.Y., Park W.B. Antiherpetic activities of flavonoids against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2)in vitro. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005;28:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/BF02978215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safrin S., Elbeik T., Phan L., Robinson D., Rush J., Elbaggari A., Mills J. Correlation between response to acyclovir and foscarnet therapy and in vitro susceptibility result for isolates of herpes simplex virus from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1246–1250. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.6.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sangdara A., Bhattarakosol P. Acyclovir susceptibility of herpes simplex virus isolates at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2008;91:908–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knebel-Mörsdorf D. Nectin-1 and HVEM: Cellular receptors for HSV-1 in skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19087–19088. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simpson S.A., Manchak M.D., Hager E.J., Krummenacher C., Whitbeck J.C., Levin M.J., Freed C.R., Wilcox C.L., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., et al. Nectin-1/HveC Mediates herpes simplex virus type 1 entry into primary human sensory neurons and fibro-blasts. J. Neurovirol. 2005;11:208–218. doi: 10.1080/13550280590924214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agelidis A.M., Shukla D. Cell entry mechanisms of HSV: What we have learned in recent years. Future Virol. 2015;10:1145–1154. doi: 10.2217/fvl.15.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gopinath S.C.B., Hayashi K., Kumar P.K.R. Aptamer That Binds to the gD Protein of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and Efficiently Inhibits Viral Entry. J. Virol. 2012;86:6732–6744. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00377-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spear P.G., Manoj S., Yoon M., Jogger C.R., Zago A., Myscofski D. Different receptors binding to distinct interfaces on herpes simplex virus gD can trigger events leading to cell fusion and viral entry. Virology. 2006;344:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Giovine P., Settembre E.C., Bhargava A.K., Luftig M.A., Lou H., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., Krummenacher C., Carfi A. Structure of Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein D Bound to the Human Receptor Nectin-1. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002277. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connolly S.A., Landsburg D.J., Carfi A., Whitbeck J.C., Zuo Y., Wiley D.C., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J. Potential Nectin-1 Binding Site on Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein D. J. Virol. 2005;79:1282–1295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1282-1295.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elion G. Acyclovir: Discovery, mechanism of action, and selectivity. J. Med. Virol. 1993;41:2–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kłysik K., Pietraszek A., Karewicz A., Nowakowska M. Acyclovir in the treatment of herpes viruses–A review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020;27:4118–4137. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180309105519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leung D.T., Sacks S.L. Docosanol: A topical antiviral for herpes labialis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2004;5:2567–2571. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.12.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pérez-Pérez M.-J., Saiz J.-C., Priego E.-M., Martín-Acebes M.A. Antivirals against (Re)emerging Flaviviruses: Should We Target the Virus or the Host? ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022;13:5–10. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scott D.E., Bayly A.R., Abell C., Skidmore J. Small molecules, big targets: Drug discovery faces the protein–protein interaction challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:533–550. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Valeur E., Guéret S.M., Adihou H., Gopalakrishnan R., Lemurell M., Waldmann H., Grossmann T., Plowright A.T. New Modalities for Challenging Targets in Drug Discovery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:10294–10323. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu H., Zhou Q., He J., Jiang Z., Peng C., Tong R., Shi J. Recent advances in the development of protein–protein interactions modulators: Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:213. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schomburg K.T., Bietz S., Briem H., Henzler A.M., Urbaczek S., Rarey M. Facing the Challenges of Structure-Based Target Prediction by Inverse Virtual Screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:1676–1686. doi: 10.1021/ci500130e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duan J., Liuzzi M., Paris W., Lambert M., Lawetz C., Moss N., Jaramillo J., Gauthier J., Deéziel R., Cordingley M.G. Antiviral Activity of a Selective Ribonucleotide Reductase Inhibitor against Acyclovir-Resistant Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 In Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1629–1635. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moss N., Beaulieu P., Duceppe J.-S., Ferland J.-M., Garneau M., Gauthier J., Ghiro E., Goulet S., Guse I., Jaramillo J., et al. Peptidomimetic Inhibitors of Herpes Simplex Virus Ribonucleotide Reductase with Improved in Vivo Antiviral Activity. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4173–4180. doi: 10.1021/jm960324r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moss N., Deziel R., Adams J., Aubry N., Bailey M., Baillet M., Beaulieu P., DiMaio J., Duceppe J.S. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 ribonucleotide reductase by substituted tetrapeptide derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:3005–3009. doi: 10.1021/jm00072a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gaudreau P., Paradis H., Langelier Y., Brazeau P. Synthesis and inhibitory potency of peptides corresponding to the subunit 2 C-terminal region of herpes virus ribonucleotide reductases. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:723–730. doi: 10.1021/jm00164a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoffman R.L., Kania R.S., Brothers M.A., Davies J.F., Ferre R.A., Gajiwala K.S., He M., Hogan R.J., Kozminski K., Li L.Y., et al. Discovery of Ketone-Based Covalent Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3CL Proteases for the Potential Therapeutic Treatment of COVID-19. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:12725–12747. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Vries M., Mohamed A.S., Prescott R.A., Valero-Jimenez A.M., Desvignes L., O’Connor R., Steppan C., Devlin J.C., Ivanova E., Herrera A., et al. A comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antivirals in human airway models characterizes 3CLpro inhibitor PF-00835231 as a potential new treatment for COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.28.272880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hassan S.T.S., Masarčíková R., Berchová-Bímová K. Bioactive natural products with anti-herpes simplex virus properties. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015;67:1325–1336. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Treml J., Gazdová M., Šmejkal K., Šudomová M., Kubatka P., Hassan S.T.S. Natural Products-Derived Chemicals: Breaking Barriers to Novel Anti-HSV Drug Development. Viruses. 2020;12:154. doi: 10.3390/v12020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vijayalakshmi U., Shourie A. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometric analysis of ethanolic extracts of Glycyrrhiza glabra Linn. roots. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2013;4:741–755. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lim T.K. Glycyrrhiza glabra. In: Lim T.K., editor. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants: Modified Stems, Roots, Bulbs. Volume 10. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2016. pp. 354–457. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gomaa A.A., Abdel-Wadood Y.A. The potential of glycyrrhizin and licorice extract in combating COVID-19 and associated conditions. Phytomed. Plus. 2021;1:100043. doi: 10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huan C., Xu Y., Zhang W., Guo T., Pan H., Gao S. Research Progress on the Antiviral Activity of Glycyrrhizin and its Derivatives in Liquorice. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:1706. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.680674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang L., Song J., Liu A., Xiao B., Li S., Wen Z., Lu Y., Du G. Research progress of the antiviral bioactivities of natural flavonoids. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020;10:271–283. doi: 10.1007/s13659-020-00257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Montana M., Montero V., Khoumeri O., Vanelle P. Quinoxaline Derivatives as Antiviral Agents: A Systematic Review. Molecules. 2020;25:2784. doi: 10.3390/molecules25122784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu Y., Tang Q., Rao Z., Fang Y., Jiang X., Liu W., Luan F., Zeng N. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus 1 by cepharanthine via promoting cellular autophagy through up-regulation of STING/TBK1/P62 pathway. Antivir. Res. 2021;193:105143. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banerjee P., Erehman J., Gohlke B.O., Wilhelm T., Preissner R., Dunkel M. Super Natural II—A database of natural products. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D935–D939. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rothwell J.A., Pérez-Jiménez J., Neveu V., Medina-Remón A., M'Hiri N., García-Lobato P., Manach C., Knox C., Eisner R., Wishart D.S., et al. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: A major update of the Phenol-Explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database. 2013;2013:bat070. doi: 10.1093/database/bat070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wishart D.S., Knox C., Guo A.C., Eisner R., Young N., Gautam B., Hau D.D., Psychogios N., Dong E., Bouatra S., et al. HMDB: A knowledgebase for the human metabolome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;37:D603–D610. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruiz-Torres V., Encinar J.A., Herranz-López M., Pérez-Sánchez A., Galiano V., Barrajón-Catalán E., Micol V. An Updated Review on Marine Anticancer Compounds: The Use of Virtual Screening for the Discovery of Small-Molecule Cancer Drugs. Molecules. 2017;22:1037. doi: 10.3390/molecules22071037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sterling T., Irwin J.J. ZINC 15–ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015;55:2324–2337. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hernandez University Molecular Docking Database Site. [(accessed on 22 May 2021)]. Available online: http://docking.umh.es.

- 83.Schrödinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.3.5. 2019. [(accessed on 15 September 2021)]. Available online: http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

- 84.Chemaxon: Software Solutions and Services for Chemistry & Biology. [(accessed on 19 August 2020)]. Available online: https://www.chemaxon.com.

- 85.O’Boyle N.M., Banck M., James C.A., Morley C., Vandermeersch T., Hutchison G.R. Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dallakyan S., Olson A.J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with pyrx. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1263:243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang N., Yan J., Lu G., Guo Z., Fan Z., Wang J., Shi Y., Qi J., Gao G.F. Binding of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D to nectin-1 exploits host cell adhesion. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:577. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. LigPlot+: Multiple ligand–protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chiang L., Chiang W., Chang M., Ng L., Lin C. Antiviral activity of Plantago major extracts and related compounds in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2002;55:53–62. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Z., Jia J., Wang L., Li F., Wang Y., Jiang Y., Song X., Qin S., Zheng K., Ye J., et al. Anti-HSV-1 activity of Aspergillipeptide D, a cyclic pentapeptide isolated from fungus Aspergillus sp. SCSIO 41501. Virol. J. 2020;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12985-020-01315-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.