Abstract

The family Boletaceae primarily represents ectomycorrhizal fungi, which play an essential ecological role in forest ecosystems. Although the Boletaceae family has been subject to a relatively global and comprehensive history of work, novel species and genera are continually described. During this investigation in northern China, many specimens of boletoid fungi were collected. Based on the study of their morphology and phylogeny, four new species, Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus, Butyriboletus subregius, Tengioboletus subglutinosus, and Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus, are introduced. Morphological evidence and phylogenetic analyses of the single or combined dataset (ITS or 28S, rpb1, rpb2, and tef1) confirmed these to be four new species. The evidence and analyses indicated the new species’ relationships with other species within their genera. Detailed descriptions, color photographs, and line drawings are provided. The species of Butyriboletus in China were compared in detail and the worldwide keys of Tengioboletus and Suillellus were given.

Keywords: Boletales, biodiversity, molecular analyses, taxonomy

1. Introduction

Boletaceae Chevall. [1], a family with more than 70 genera, is one of the most prominent and diverse among the basidiomycetes [2]. It is mainly characterized by being tubulose with infrequent lamellate or loculate hymenophora, and by a fleshy context. Most Boletaceae species have value for humans and are essential for mutualistic symbiosis with trees [3,4,5,6]. Although the family Boletaceae was established nearly two centuries ago, the species diversity of the family increased significantly in the last few decades [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Because the morphology of Boletaceae has convergent characteristics, the classification did not correspond to the phylogeny of Boletaceae for a long time. With the development of molecular biology, the method of genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition (GCPSR) [20] was used to identify species of fungi, resolved some doubts about the status of taxa, and contributed to a better understanding of the relationships of the genera in this family [5,21,22]. In the past two decades, new genera and new species have rapidly increased, and the evolution of ectomycorrhizas of Boletales was gradually disclosed [23,24].

In China, the family Boletaceae has continued to receive increasing attention from mycologists [5,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. However, the previous studies were focused on southern China, and the species diversity remained unclear in northern China. During previous field collection in the north of China, we obtained many specimens. Based on our analyses of their morphology and phylogeny, we propose four new species: Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus, Butyriboletus subregius, Tengioboletus subglutinosus, and Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus.

Butyriboletus was erected by Arora et al. [33] to accommodate the Boletus sect. Appendiculati. It is characterized by a reddish to brown pileus and a yellow hymenophore, usually staining blue when bruised. Five species have been described in China, i.e., Bu. huangnianlaii N.K. Zeng, H. Chai & Zhi Q. Liang [28], Bu. pseudospeciosus Kuan Zhao & Zhu L. Yang [5], Bu. roseoflavus (Hai B. Li & Hai L. Wei), D. Arora & J.L. Frank [33], Bu. sanicibus D. Arora & J.L. Frank [33], and Bu. yicibus D. Arora & J.L. Frank [32].

Tengioboletus was established by Wu et al. [5], including three species: T. glutinosus G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang, T. reticulatus G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang, and T. fujianensis N.K. Zeng & Zhi Q. Liang [5,34]. Tengioboletus can be distinguished easily from other Boletaceae genera by combining the following characteristics: a yellow context; hymenophore that change color when injured; tubes that are concolorous with the surface; cystidia that are scattered; subfusiform-ventricose or clavate shape; and an epithelium to ixotrichodermium pileipellis.

Suillellus, typified by Boletus luridus Schaeff, was established by Murrill in 1909 [7]. According to Vizzini et al. [13], Suillellus s.str. is characterized by basidiomata that are usually slender, stipes that are cylindrical and sometimes covered with reticulation, pileus that are reddish brown to olivaceous and turn to blue when bruised, the presence or absence of Bataille’s line, and a context that is reddish in the stipe base and bluing when exposed to air and positive amyloid reaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samplings and Morphological Analyses

Materials were collected from Jilin province and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of Mycology of the Jilin Agriculture University (HMJAU). Descriptions of the colors of basidiomata used color coding from Kornerup and Wanscher [35]. The micro-morphological structures were performed in a 5% KOH solution and then in a 1% Congo Red or Melzer’s reagent solution. The amyloid reaction was tested following Imler’s procedure [36,37]. The abbreviations for basidiospore measurements (n/m/p) indicate “n” basidiospores from “m” basidiomata of “p” specimens. The sizes of basidiospores are given as (a) b–m–c (d), where “a” is the smallest value, “d” is the largest value, “m” is the average value point, and “b–c” covers a minimum of 95% of the values. “Q” stands for the ratio of the length and the width of the basidiospores and “Q ± av” stands for for the average Q of all basidiospores ± sample standard deviation. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to observe the ultrastructure of the spores.

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from dried specimens, using the NuClean Plant Genomic DNA kit (CWBIO). For the amplification of ITS, 28S, rpb1, rpb2, and tef1, we used primer pairs ITS1/4, LROR/LR5, RPB1-B-F/RPB1-B-R, RPB2-B-F1/RPB2-B-R, and 983F/1567R, respectively [5,22,25,38,39,40,41,42]. PCR amplification procedures were set to refer to Zhang et al. [43], White et al. [39], and Kuo and Ortiz-Santana [44]. Then, PCR productions were sent to Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) to be directly sequenced using the ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer.

2.3. Data Analysis

Newly generated sequences were uploaded to NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 10 January 2022), as shown in Table 1, with other similar sequences downloaded from the NCBI and UNITE (https://unite.ut.ee/, accessed on 10 January 2022) datasets. DNA sequences were aligned and manually modified using Bioedit v7.1.3 [45]. In the multi-locus dataset (28S + rpb1 + rpb2 + tef1) of Tengioboletus, 894 bp for 28S, 758 bp for rpb1, 710 bp for rpb2, and 638 bp for tef1, and in the four-locus dataset (tef1 + 28S + rpb2 + ITS) of Butyriboletus, 730 bp for tef1, 863 bp for 28S, 834 bp for rpb2, and 809 bp for ITS. The data used for phylogenetic analyses for Suillellus included the ITS dataset and a multi-locus dataset (tef1 + 28S + rpb1 + rpb2), For the multi-locus dataset, 907 bp for 28S, 791 bp for rpb1, 719 bp for rpb2, and 631 bp for tef1. The best models of the multi-locus datasets were searched via PartitionFinder 2 [46]. Meanwhile, the best model of the ITS dataset was searched via Modelfinder [47]. Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using the maximum likelihood method (ML) and the Bayes inference (BI) method. The models employed for each of the four loci of Tengioboletus, and Butyriboletus were GTR + I + G for 28S, SYM + G for rpb1, K80 + G for rpb2, SYM + I + G for tef1, and GTR + I + G for ITS, GTR + I + G for 28S, K80 + G for rpb2, SYM + I + G for tef1, respectively. For the multi-locus dataset of Suillellus, the best models for each locus were K80 + I + G for rpb1 and SYM + I + G for 28S, rpb2, and tef1. In the ITS dataset of Suillellus, the best models for ML analysis and BI analyses were K2P + I + G4. For ML analyses, the datasets were analyzed using IQ-TREE [48] under an ultrafast bootstrap, with 5000 replicates. For BI analyses, the multi-locus datasets were analyzed using MrBayes 3.2.6 [49], running in a total of 2,000,000 generations, and sampled every 1000 generations. The initial 25% of the sampled data were discarded as burn-in. Other parameters were kept at their default settings.

Table 1.

Information of DNA sequences used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees. Sequences newly generated in this study are indicated in bold.

| Taxon | Voucher ID | ITS | 28S | TEF1 | RPB1 | RPB2 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tengioboletus glutinosus | HKAS53425 | – | KF112341 | KF112204 | KF112578 | KF112800 | [22] |

| T. glutinosus | HKAS53452 | – | KT990655 | KT990844 | KT990994 | KT990480 | [5] |

| T. reticulatus | HKAS53426 | – | KF112491 | KF112313 | KF112649 | KF112828 | [22] |

| T. reticulatus | HKAS52241 | – | KT990657 | KT990845 | KT990995 | KT990481 | [5] |

| T. reticulatus | HKAS53453 | – | KT990656 | KT990846 | – | KT990482 | [5] |

| T. funjianensis | HKAS76661 | – | KF112342 | KF112205 | – | KF112801 | [22] |

| T. funjianensis | HKAS77869 | – | KT990658 | KT990847 | KT990996 | KT990483 | [5] |

| T. subglutinosus | HMJAU59034 (T286) | – | OL588198 | OL739119 | OL739121 | – | this study |

| T. subglutinosus | HMJAU59035 (T293) | – | OL588197 | OL739120 | OL739122 | OL739118 | this study |

| Porphyrellus porphyrosporus | MB97-023 | – | DQ534643 | GU187734 | GU187475 | GU187800 | [50] |

| P. porphyrosporus | HKAS76671 | – | KF112482 | KF112243 | KF112611 | KF112718 | [22] |

| Tylopilus sp. | HKAS50211 | – | KT990552 | KT990752 | KT990920 | KT990389 | [22] |

| Tylopilus sp. | HKAS59826 | – | KT990558 | – | – | – | [5] |

| Tylopilus sp. | HKAS90198 | – | KT990559 | – | – | – | [5] |

| Strobilomyces atrosquamosus | HKAS55368 | – | KT990648 | KT990839 | KT990989 | KT990476 | [5] |

| S. atrosquamosus | HKAS78563 | – | KT990649 | KT990833 | KT990983 | KT990470 | [5] |

| S. echinocephalus | HKAS59420 | – | KF112463 | KF112256 | KF112600 | KF112810 | [22] |

| P. aff. alboater | HKAS55375 | – | KT990622 | KT990816 | KT990969 | – | [5] |

| P. nigropurpureus | HKAS74938 | – | KF112466 | KF112246 | – | KF112763 | [22] |

| P. nigropurpureus | HKAS52685 | – | KT990627 | KT990821 | KT990973 | KT990459 | [5] |

| P. nigropurpureus | HKAS53370 | – | KT990628 | KT990822 | KT990974 | KT990460 | [5] |

| P. holophaeus | HKAS50508 | – | KF112465 | KF112244 | KF112553 | – | [22] |

| P. holophaeus | HKAS74894 | – | KF112474 | KF112245 | KF112554 | – | [22] |

| P. castaneus | HKAS63076 | – | KT990548 | KT990749 | KT990916 | KT990386 | [5] |

| P. castaneus | HKAS52554 | – | KT990697 | KT990883 | KT991026 | KT990502 | [5] |

| P. orientifumosipes | HKAS75078 | – | KF112481 | KF112242 | – | KF112717 | [22] |

| P. orientifumosipes | HKAS53372 | – | KT990629 | KT990823 | KT990975 | KT990461 | [5] |

| Boletus bainiugan | HKAS52235 | – | KF112457 | KF112203 | KF112587 | KF112705 | [22] |

| B. bainiugan | HKAS55393 | – | JN563852 | – | JN563868 | – | [51] |

| B. fagacicola | HKAS55975 | – | JN563853 | – | JN563879 | – | [51] |

| B. fagacicola | HKAS71347 | – | JQ172790 | – | JQ172791 | – | [51] |

| Xanthoconium affine | NY00815399 (REH8660) | – | KT990661 | KT990850 | KT990999 | KT990486 | [5] |

| X. porophyllum | HKAS90217 | – | KT990662 | KT990851 | KT991000 | KT990487 | [5] |

| Baorangia pseudocalopus | HKAS63607 | – | KF112355 | KF112167 | – | – | [22] |

| Ba. pseudocalopus | HKAS75081 | – | KF112356 | KF112168 | – | – | [22] |

| Butyriboletus abieticola | Arora11087 | KC184412 | KC184413 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. appendiculatus | Bap1 | KJ419923 | AF456837 | JQ327025 | – | – | [52] |

| Bu. appendiculatus | BR50200893390-25 | KT002598 | KT002609 | KT002633 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. appendiculatus | BR50200892955-50 | KJ605668 | KJ605677 | KJ619472 | – | KP055030 | [54] |

| Bu. appendiculatus | MB000286 | KT002599 | KT002610 | KT002634 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. autumniregius | Arora11108 | KC184423 | KC184424 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. brunneus | NY00013631 | KT002600 | KT002611 | KT002635 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. fechtneri | AT2003097 | KC584784 | KF030270 | – | – | – | [21] |

| Exsudoporus frostii | JLF2548 | KC812303 | KC812304 | – | – | – | [33] |

| E. frostii | NY815462 | – | JQ924342 | KF112164 | – | KF112675 | [22] |

| E. floridanus | BOS 617, BZ 3170 | MN250222 | MK601725 | MK721079 | – | MK766287 | [43] |

| Bu. hainanensis | N.K. Zeng 1197 (FHMU 2410) | KU961653 | KU961651 | – | – | KU961658 | [32] |

| Bu. hainanensis | N.K. Zeng 2418 (FHMU 2437) | KU961654 | KU961652 | KU961656 | – | KX453856 | [32] |

| Bu. huangnianlaii | N.K. Zeng 3245 (FHMU 2206) | MH885350 | MH879688 | MH879717 | – | MH879740 | [28] |

| Bu. huangnianlaii | N.K. Zeng 3246 (FHMU 2207) | MH885351 | MH879689 | MH879718 | – | MH879741 | [28] |

| Bu. peckii | 3959 | – | JQ326999 | JQ327026 | – | – | [55] |

| Bu. persolidus | Arora11110 | KC184444 | – | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. primiregius | DBB00606 | – | KC184451 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. fuscoroseus | BR50201618465-02 | KT002602 | KT002613 | KT002637 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. fuscoroseus | BR50201533559-51 | KT002603 | KT002614 | KT002638 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. pseudospeciosus | HKAS59467 | – | KF112331 | KF112176 | – | KF112672 | [22] |

| Bu. pseudospeciosus | HKAS63513 | – | KT990541 | KT990743 | – | KT990380 | [5] |

| Bu. pseudospeciosus | HKAS63596 | – | KT990542 | KT990744 | – | KT990381 | [5] |

| Bu. pseudospeciosus | N.K. Zeng 2127 (FHMU 1391) | MH885349 | MH879687 | MH879716 | – | – | [28] |

| Bu. fuscoroseus | MG383a | KC184458 | – | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. pulchriceps | DS4514 | – | KF030261 | KF030409 | – | – | [21] |

| Bu. pulchriceps | R. Chapman 0945 | KT002604 | KT002615 | KT002639 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. querciregius | Arora11100 | KC184461 | – | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. regius | MB000287 | KT002605 | KT002616 | KT002640 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. regius | MG408a | KC584789 | KC584790 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. regius | PRM:923465 | KJ419920 | KJ419931 | – | – | – | [56] |

| Bu. roseoflavus | Arora11054 | KC184434 | KC184435 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. roseoflavus | HKAS63593 | KJ909517 | KJ184559 | KJ184571 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. roseoflavus | HKAS54099 | KJ909519 | KF739665 | KF739779 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. roseoflavus | N.K. Zeng 2123 (FHMU 1387) | MH885348 | MH879686 | MH879715 | – | – | [28] |

| Bu. pseudoroseoflavus | HMJAU59470 (T274) | OL604164 | OL587853 | OL739124 | – | OL739126 | this study |

| Bu. pseudoroseoflavus | HMJAU59471 (R383) | OL604165 | OL587852 | OL739123 | – | OL739125 | this study |

| Bu. Roseopurpureus | E.E. Both3765 | KT002606 | KT002617 | KT002641 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. Roseopurpureus | JLF2566 | KC184466 | KC184467 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. Roseopurpureus | MB06-059 | KC184464 | KF030262 | KF030410 | – | – | [21] |

| Bu. sanicibus | Arora99211 | KC184469 | KC184470 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. subregius | HMJAU60200 (T95) | OM237336 | OM237339 | OM285111 | – | OM285109 | this study |

| Bu. subregius | HMJAU60201 (T198) | OM237337 | OM237340 | OM285112 | – | OM285110 | this study |

| Butyriboletus sp. | MHHNU7456 | – | KT990539 | KT990741 | – | KT990378 | [5] |

| Butyriboletus sp. | HKAS52525 | – | KF112337 | KF112163 | – | KF112671 | [22] |

| Butyriboletus sp. | HKAS57774 | – | KF112330 | KF112155 | – | KF112670 | [22] |

| Bu. hainanensis | HKAS59814 | – | KF112336 | KF112199 | – | KF112699 | [22] |

| Butyriboletus yicibus | HKAS63528 | – | KF112332 | KF112156 | – | KF112673 | [22] |

| Bu. Subappendiculatus | MB000260 | KT002607 | KT002618 | KT002642 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. subsplendidus | HKAS52661 | – | KF112339 | KF112169 | – | KF112676 | [5] |

| Bu. taughannockensis | 263101 | MH257559 | MH236172 | – | – | – | |

| Bu. taughannockensis | 250839 | MH234472 | MH234473 | – | – | – | |

| Bu. taughannockensis | 252208 | MH236100 | MH236099 | – | – | – | |

| Bu. yicibus | Arora9727 | KC184474 | KC184475 | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. yicibus | HKAS57503 | KT002608 | KT002620 | KT002644 | – | – | [53] |

| Bu. yicibus | HKAS68010 | KJ909521 | KT002619 | KT002643 | – | – | [53] |

| Gymnogaster boletoides | NY01194009 (REH9455) | – | KT990572 | KT990768 | – | KT990406 | [5] |

| Rugiboletus brunneiporus | HKAS83209 | – | KM605134 | KM605144 | – | KM605168 | [27] |

| R. extremiorientalis | HKAS63635 | – | KF112403 | KF112198 | – | KF112720 | [22] |

| Crocinoboletus laetissimus | HKAS50232 | — | KT990567 | KT990762 | KT990925 | — | [5] |

| C. laetissimus | HKAS59701 | — | KF112436 | — | — | KF112711 | [22] |

| C. rufoaureus | HKAS53424 | — | KF112435 | KF112206 | KF112533 | KF112710 | [22] |

| C. rufoaureus | HKAS59820 | — | KF112434 | — | KF112532 | KF112709 | [22] |

| Cyanoboletus brunneoruber | HKAS63504 | — | KF112368 | KF112194 | KF112531 | KF112702 | [22] |

| Cy. brunneoruber | HKAS80579 (1) | — | KT990568 | KT990763 | KT990926 | KT990401 | [5] |

| Cy. brunneoruber | HKAS80579 (2) | — | KT990569 | KT990764 | KT990927 | KT990402 | [5] |

| Cy. instabilis | HKAS59554 | — | KF112412 | KF112186 | KF112528 | KF112698 | [22] |

| Cy. pulverulentus | 9606 | — | KF030313 | KF030418 | KF030364 | — | [21] |

| Baorangia pseudocalopus | HKAS63607 | — | KF112355 | KF112167 | KF112519 | KF112677 | [22] |

| Ba. pseudocalopus | HKAS75081 | — | KF112356 | KF112168 | KF112520 | KF112678 | [22] |

| Lanmaoa angustispora | HKAS74765 | — | KF112322 | KF112159 | KF112521 | KF112680 | [22] |

| L. angustispora | HKAS74752 | — | KM605139 | KM605154 | KM605166 | KM605177 | [27] |

| L. angustispora | HKAS74759 | — | KM605140 | KM605155 | KM605167 | KM605178 | [27] |

| L. asiatica | HKAS54094 | — | KF112353 | KF112161 | KF112522 | KF112682 | [22] |

| L. asiatica | HKAS63516 | — | KT990584 | KT990780 | KT990935 | KT990419 | [5] |

| L. fragrans | 18555 | JF907800 | – | – | – | – | |

| Neoboletus brunneissimus | HKAS52660 | — | KF112314 | KF112143 | KF112492 | KF112650 | [22] |

| N. hainanaensis | HKAS63515 | — | KT990614 | KT990808 | KT990964 | KT990449 | [5] |

| N. ferrugineus | HKAS77617 | — | KT990595 | KT990788 | KT990943 | KT990430 | [5] |

| N. ferrugineus | HKAS77718 | — | KT990596 | KT990789 | KT990944 | KT990431 | [5] |

| N. flavidus | HKAS59443 | — | KU974139 | KU974136 | KU974142 | KU974144 | [5] |

| N. flavidus | HKAS58724 | — | KU974140 | KU974137 | KU974143 | KU974145 | [5] |

| Porphyrellus castaneus | HKAS52554 | — | KT990697 | KT990883 | KT991026 | KT990502 | [5] |

| P. castaneus | HKAS63076 | — | KT990548 | KT990749 | KT990916 | KT990386 | [5] |

| P. castaneus | HKAS68575 | — | KT990560 | — | — | — | [5] |

| P. holophaeus | HKAS59407 | — | KT990708 | KT990888 | KT991030 | KT990506 | [5] |

| P. nigropurpureus | HKAS52685 | — | KT990627 | KT990821 | KT990973 | KT990459 | [5] |

| P. nigropurpureus | HKAS53370 | — | KT990628 | KT990822 | KT990974 | KT990460 | [5] |

| P. orientifumosipes | HKAS75078 | — | KF112481 | KF112242 | — | KF112717 | [22] |

| P. orientifumosipes | HKAS53372 | — | KT990629 | KT990823 | KT990975 | KT990461 | [5] |

| Rubroboletus dupainii | JAM0607 | — | — | KF030413 | KF030361 | — | [21] |

| R. latisporus | HKAS63517 | — | KP055022 | KP055019 | KP055025 | KP055028 | [25] |

| R. latisporus | HKAS80358 | — | KP055023 | KP055020 | KP055026 | KP055029 | [25] |

| R. rhodosanguineus | 4252 | — | KF030252 | KF030412 | — | — | [21] |

| R. rhodoxanthus | HKAS84879 | — | KT990637 | KT990831 | KT990981 | KT990468 | [5] |

| R. sinicus | HKAS68620 | — | KF112319 | KF112146 | KF112504 | KF112661 | [22] |

| R. sinicus | HKAS56304 | — | KJ605673 | KJ619483 | KJ619482 | KP055031 | [54] |

| Suillellus amygdalinus | 112605ba | — | JQ326996 | JQ327024 | KF030360 | — | [55] |

| S. amygdalinus | NY00035656 (Thiers54483) | — | KT990650 | KT990840 | KT990990 | KT990477 | [5] |

| S. subamygdalinus | HKAS57262 | — | KF112316 | KF112174 | KF112501 | KF112660 | [22] |

| S. subamygdalinus | HKAS53641 | — | KT990651 | KT990841 | KT990991 | KT990478 | [5] |

| S. subamygdalinus | HKAS57953 | — | KT990652 | KT990842 | KT990992 | — | [5] |

| S. subamygdalinus | HKAS74745 | — | KT990653 | KT990843 | KT990993 | KT990479 | [5] |

| S. lacrymibasidiatus | HMJAU60202 (W3194) | OM237315 | OM230174 | OM285117 | OM285113 | OM285115 | this study |

| S. lacrymibasidiatus | HMJAU60203 (W3229) | OM237338 | OM230172 | OM285116 | – | OM285114 | this study |

| Sutorius eximius | REH9400 | — | JQ327004 | JQ327029 | — | — | [55] |

| Su. eximius | HKAS52672 | — | KF112399 | KF112207 | KF112584 | KF112802 | [22] |

| Su. luridiformis | AT1998054 | UDB000658 | – | – | – | – | |

| Tylopilus alpinus | HKAS55438 | — | KF112404 | KF112191 | KF112538 | KF112687 | [22] |

| Ty. argillaceus | HKAS90201 | — | KT990588 | KT990783 | — | — | [5] |

| Ty. argillaceus | HKAS90186 | — | KT990589 | KT990784 | — | KT990424 | [5] |

| Ty. atripurpureus | HKAS50208 | — | KF112472 | KF112283 | KF112620 | KF112799 | [22] |

| Ty. badiceps | MB03-052 | — | KF030336 | — | — | — | [21] |

| Ty. badiceps | 78206 | — | KF030335 | KF030429 | — | — | [21] |

| Veloporphyrellus alpinus | HKAS68301 | — | JX984538 | JX984550 | — | — | [57] |

| V. alpinus | HKAS57490 | — | KF112380 | KF112209 | KF112555 | KF112733 | [22] |

| V. conicus | BZ2408 | — | JX984545 | — | — | — | [57] |

| V. conicus | BZ1670 | — | JX984543 | JX984555 | — | — | [57] |

| V. gracilioides | HKAS53590 | — | KF112381 | KF112210 | KF112556 | KF112734 | [22] |

| Zangia citrina | HKAS52677 | — | HQ326940 | HQ32687 | — | — | [58] |

| Z. citrina | HKAS52684 | — | HQ326941 | HQ326872 | — | — | [58] |

| Z. erythrocephala | HKAS52843 | — | HQ326943 | — | — | — | [58] |

| Z. erythrocephala | HKAS52844 | — | HQ326944 | — | — | — | [58] |

| Z. olivaceobrunnea | HKAS52275 | — | HQ326947 | HQ326875 | — | — | [58] |

| Z. roseola | HKAS75046 | — | KF112414 | KF112269 | KF112579 | KF112791 | [22] |

| S. luridus | IB2004270 | EF644104 | – | – | – | – | [59] |

| S. luridus | 18902 | JF907802 | – | – | – | – | [60] |

| S. luridus | 18182 | JF907793 | – | – | – | – | [60] |

| S. luridus | Blu3 | AY278765 | – | – | – | – | [61] |

| S. luridus | AMB12636 | KC734542 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. luridus | AMB12638 | KC734544 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. luridus | TL-6877 | AJ889930 | – | – | – | – | |

| S. luridus | TL-6877 | UDB000077 | – | – | – | – | |

| S. luridus | 1968 | AY278766 | – | – | – | – | [61] |

| S. luridus | BL2-VII-10 | JQ685714 | – | – | – | – | [61] |

| S. luridus | AT-04 | UDB002401 | – | – | – | – | |

| S. luridus | UP12 | DQ658866 | – | – | – | – | [62] |

| S. luridus | 17696 | JF907789 | – | – | – | – | [60] |

| S. luridus | BL1-VII-09 | JQ685715 | – | – | – | – | |

| S. luridus | MA-Fungi 47706 | AJ419191 | – | – | – | – | [63] |

| S. mendax | AMB12632 | KC734547 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. mendax | AMB12633 | KC734548 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. mendax | AMB12634 | KC734543 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. mendax | AMB12635 | KC734545 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. mendax | AMB12637 | KC734540 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| S. mendax | AMB12640 | KC734541 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| Boletus luridus | UF107 | HM347662 | – | – | – | – | |

| B. amygdalinus | src491 | DQ974705 | – | – | – | – | [64] |

| B. comptus | 17827 | JF907791 | – | – | – | – | [60] |

| B. comptus | AMB12639 | KC734539 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| B. queletii | 17196 | JF907784 | – | – | – | – | [60] |

| B. queletii | 17208 | JF907785 | – | – | – | – | [60] |

| B. queletii | AMB12641 | KC734546 | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| B. queletii | JV01-231 | UDB000760 | – | – | – | – | |

| N. erythropus | MA-Fungi 47702 | AJ419188 | – | – | – | – | [63] |

| N. erythropus | BOER_TO_2 (AAM630/06) | FM958177 | – | – | – | – | |

| N. erythropus | UF278 | HM347644 | – | – | – | – | |

| N. erythropus | UF276 | HM347643 | – | – | – | – | |

| N. erythropus | UF269 | HM347665 | – | – | – | – | |

| N. erythropus | DG05-54 | UDB001523 | – | – | – | – | |

| N. erythropus | SU46 | DQ131633 | – | – | – | – | [65] |

| N. erythropus | SU47 | DQ131634 | – | – | – | – | [65] |

| N. erythropus | Daniels 582 | AJ496595 | – | – | – | – | [63] |

| Caloboletus calopus | AT1998059 | UDB000659 | – | – | – | – | |

| Ca. radicans | TUF106003 | UDB003224 | – | – | – | – | |

| Bu. fuscoroseus | AH96025 | UDB000649 | – | – | – | – | |

| Bu. fuscoroseus | AT1996017 | UDB000652 | – | – | – | – | |

| Bu. fechtneri | AT2003097 | UDB000703 | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Imperator rhodopurpureus | AT1996058 | UDB000654 | – | – | – | – | |

| R. pulchrotinctus | GS0860 | UDB000407 | – | – | – | – | |

| R. satanas | AT1998051 | UDB000415 | – | – | – | – | |

| R. rubrosanguineus | GS0405 | UDB000410 | – | – | – | – | |

| R. rhodoxanthus | AT2000182 | UDB001116 | – | – | – | – | |

| Cyanoboletus pulverulentus | RT00004 | EU819502 | – | – | – | – | |

| Cyanoboletus pulverulentus | AH97030 | UDB000408 | – | – | – | – | [66] |

| B. aestivalis | AT2004040 | UDB001113 | – | – | – | – | |

| B. aereus | AT2000198 | UDB000943 | – | – | – | – |

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Phylogeny

The four-locus dataset (28S + rpb1 + rpb2 + tef1) of Tengioboletus (Supplementary File S1) contained 33 sequences and 3000 bp nucleotide sites. The alignment was submitted to TreeBASE (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S29030, accessed on 15 January 2022). Because the ML tree’s topology was the same as the BI tree’s topology, only the ML tree was shown (Figure 1). Xanthoconium affine (Peck) Singer and Xanthoconium porophyllum G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang were chosen as outgroups. The phylogenetic tree showed that two T. subglutinosus sequences formed an independent lineage, with bootstrap proportions (BP) = 100 and posterior probability (PP) = 1, and formed a sister group with T. glutinosus (BP = 100, PP = 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Tengioboletus inferred from ML analysis. BP value (>70) and PP value (>8) are shown around branches. Our new species sequences are indicated in bold.

The four-locus dataset (ITS + 28S + tef1 + rpb2) of Butyriboletus (Supplementary File S2) consisted of 58 taxa and 3011 nucleotide sites (Figure 2). The alignment was submitted to TreeBASE (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S29034, accessed on 15 January 2022). Baorangia pseudocalopus (Hongo) G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang was chosen as the outgroup. The phylogram indicated our collections—HMJAU59471, HMJAU59470, and HMJAU60200, HMJAU60201—were grouped together respectively and formed two independent lineages with high support value (BP = 100, PP = 1 and BP = 99, PP = 1).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Butyriboletus inferred from ML analysis. BP value (>70) and PP value (>9) are shown around branches. Our new species sequences are indicated in bold.

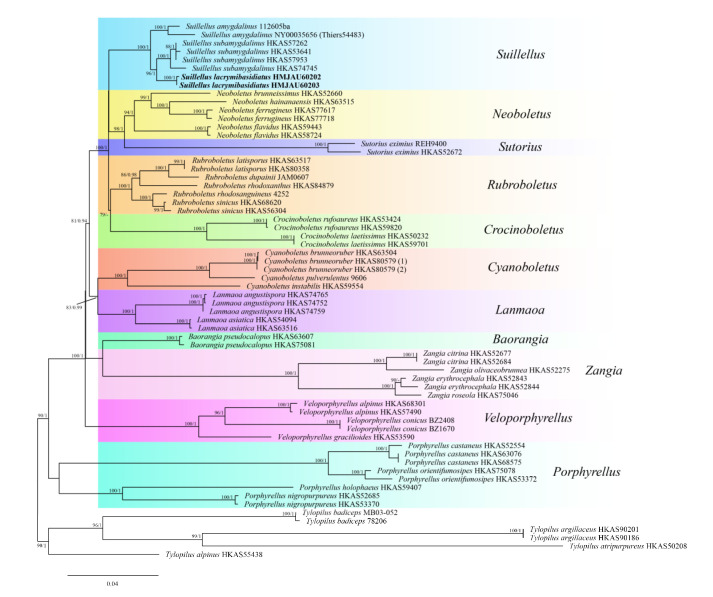

The four-locus dataset (28S + rpb1 + rpb2 + tef1) of Suillellus (Supplementary File S3) involved 64 taxa and 3048 bp sites. Tylopilus alpinus Y.C. Li & Zhu L. Yang and Tylopilus atripurpureus (Corner) E. Horak were selected as outgroups. The alignment was submitted to TreeBASE (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S29037, accessed on 15 January 2022). The phylogram showed our species belongs to Suillellus (Figure 3). It formed an independent sister clade to Suillellus subamygdalinus Kuan Zhao & Zhu L. Yang, with a solid support (BP = 92, PP = 1). The ITS dataset of Suillellus (Supplementary File S4) consisted of 55 taxa and 885 bp sites. Boletus aestivalis (Paulet) Fr. and Boletus aereus Bull. were chosen as outgroups (Figure 4). The alignment was submitted to TreeBASE (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S29087, accessed on 15 January 2022). The phylogram showed that our species was close to Suillellus comptus (Simonini) Vizzini, Simonini & Gelardi and formed an independent and robust support clade (BP = 98, PP = 1).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of Suillellus inferred from ML analysis based on the multi-locus dataset. BP value (>70) and PP value (>9) are shown around branches. Our new species sequences are indicated in bold.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of Suillellus inferred from Bayes inference analysis based on ITS dataset. BP value (>70) and PP value (>9) are shown around branches. Our new species sequences are indicated in bold.

3.2. Taxonomy

Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus Yang Wang, Bo Zhang & Yu Li, sp. nov.

Mycobank No.: 842167.

Figure 5e, Figure 6 and Figure 7d.

Figure 5.

Basidiomata of boletes. (a–c) Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus; (d) Butyriboletus subregius; (e) Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus (e from HMJAU 59470); (f) Tengioboletus subglutinosus (f from HMJAU 59037). (a–c) Photos by Yang Wang; (d–f) Photos by Yong-Lan Tuo.

Figure 6.

Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus. (a) Basidiospores; (b) Basidia and pleurocystidia; (c) Pileipellis; (d) Stipitipellis; (e) Pleurocystidia; (f) Cheilocystidia. Scale bars: (b–e) =10 μm; (a,f) =5 μm.

Figure 7.

Basidiospores observed in the SEM. (a,b) Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus; (c) Butyriboletus subregius; (d) Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus; (e,f) Tengioboletus subglutinosus.

Etymology. The epithet “pseudoroseoflavus” refers to its similarity to B. roseoflavus.

Holotypus. China. Jilin Province, Jian city, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, 125°34′33″ E, 40°52′7″ N, under Quercus mongolica, on dark-brown soil, alt. 1210 m, 16 August 2019, Gu Rao 383 (HMJAU 59471!).

Basidiomata large. Pileus 13.5–17.0 cm in diameter, hemispherical to applanate, with slightly or distinctly appendiculate margin, sometimes incurved at the margin when young; surface tomentose, pink (12A4) to greyish rose (11B5), context 1.1–1.8 cm thick, light yellow (1A5), unchanging in color when injured. Hymenophore adnate to decurrent, surface greenish yellow (1B8), becoming greenish blue (23B8) quickly when bruised; pores round to angular, ca. 1–3/mm; tubes 1.5–1.7 cm long, concolorous with pore surface, unchanging color when injured. Stipe 9.0–14.7 × 2.0–3.6 cm, subcylindrical, robust, yellow on the upper portion, vivid red (10A8) downwards, surface almost wholly covered yellow (2B8) reticulation or at least upper two thirds; basal mycelium white.

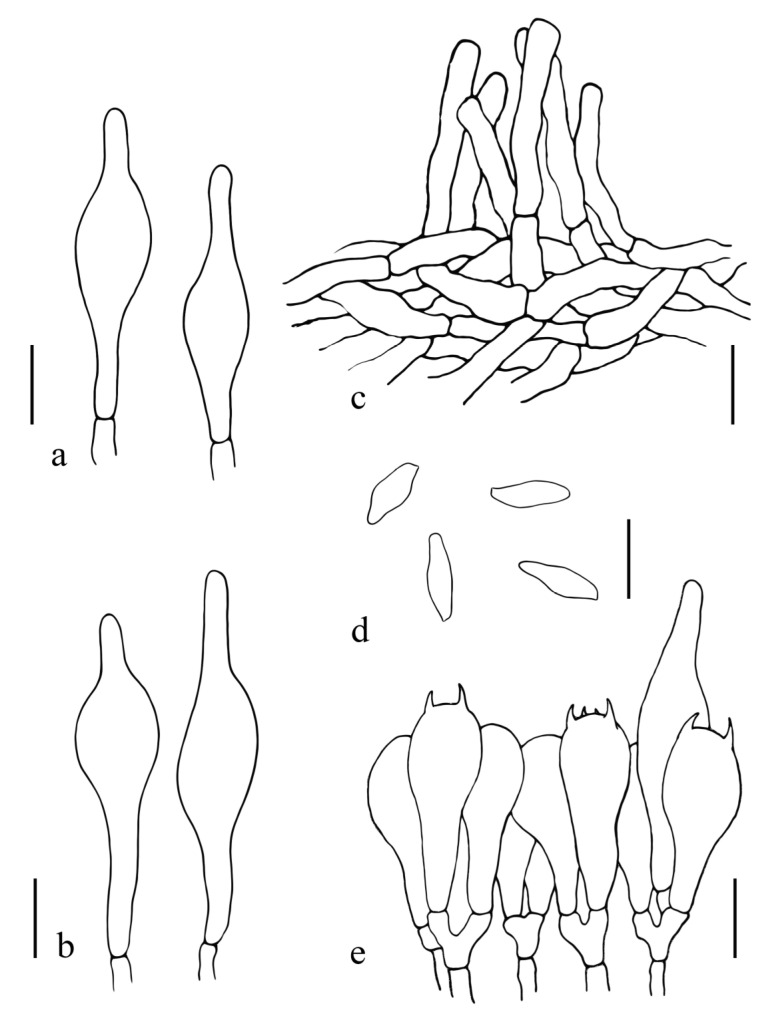

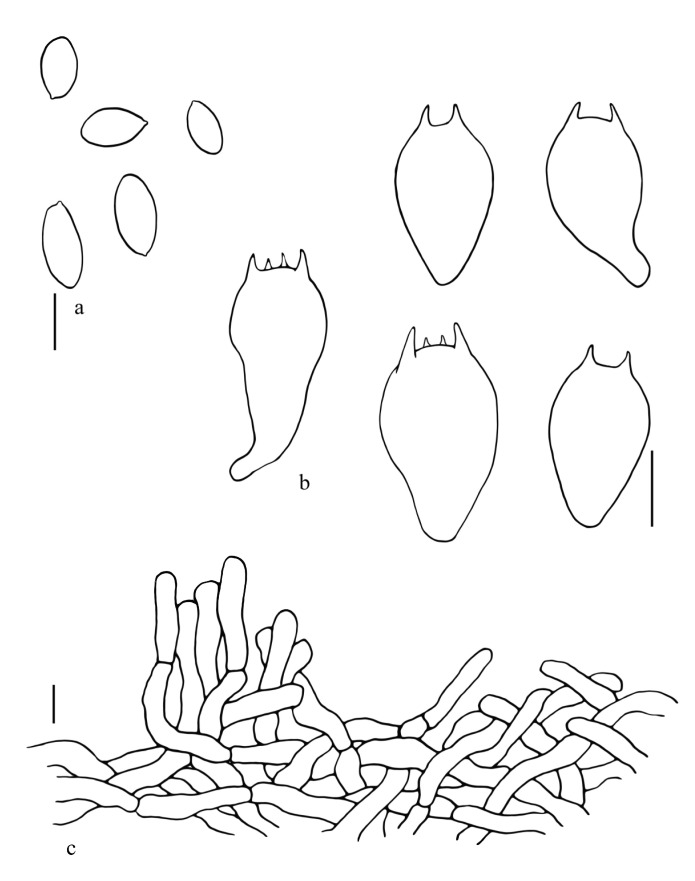

Basidiospores (60/3/2) (7.0) 10.2–10.6–11.0 (16.0) × (2.0) 3.1–3.2–3.7 (4.0) μm, Q = (2.0) 2.5–4.6 (5.3), Qm = 3.30 ± 0.58, elongate oblong to subfusoid, inequilateral with a suprahilar depression in side view, light yellow in 5% KOH, smooth. Hymenophoral trama boletoid, hyphae cylindrical, 2.5–10 μm wide. Basidia clavate, thin-walled, 16.0–33.0 × 2.0–10.0 μm, 2- and 4-spored. Cheilocystidia 31.5–50.0 × 5.0–10.0 μm, narrowly lageniform, thin-walled, pale yellow in 5% KOH. Pleurocystidia 37.5–62.5 × 5.0–11.5 μm, similar to cheilocystidia in shape. Pileipellis trichodermium, filamentous hyphae 1.7–7.5 μm wide. Stipitipellis fertile, hymeniform with thin-walled and inflated terminal cells (13.8–26.0 × 6.8–13.8 μm). Stipe trama composed of parallel hyphae 2.5–7.5 μm wide. Clamp connections not observed.

Habitat: solitary or scattered on a dark-brown soil of Quercus mongolica forest.

Known distribution: currently, only known from Jilin province, China.

Additional collection examined: China. Jilin Province, Jian city, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, 125°34′33″ E, 40°52′7″ N, under Quercus mongolica, on dark-brown soil, alt. 950 m, 5 August 2020, Yong-Lan Tuo 274 (HMJAU 59470).

Notes: Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus is characterized by a pink to greyish rose pileus, greenish yellow pores changing to greenish blue when bruised, a stipe surface almost wholly covered with yellow reticulation, a stipe of unchanging color when injured, and large and narrow basidiospores. Morphologically and phylogenetically, Bu. pseudoroseoflavus is similar to Bu. roseoflavus (Hai B. Li & Hai L. Wei) D. Arora & J.L. Frank, which was initially described in specimens from eastern China (Zhejiang province) and southwestern China (Yunnan province) by Li et al. [67]. However, Bu. pseudoroseoflavus differs from Bu. roseoflavus in its adnate to decurrent hymenophore and its relatively larger and narrower basidiospores, with a more considerable Q value and pleurocystidia larger than cheilocystidia [5]. In morphological features, Bu. pseudoroseoflavus is also similar to Bu. cepaeodoratus (Taneyama & Har. Takah.) Vizzini & Gelardi, Bu. roseogriseus (Šutara, M. Graca, M. Kolařík, Janda & Kříž) Vizzini & Gelardi, Bu. primiregius D. Arora & J.L. Frank, Bu. regius (Krombh.) D. Arora & J.L. Frank., and Bu. fuscoroseus (Smotl.) Vizzini & Gelardi, but the pileus of Bu. cepaeodoratus always has a duller color, its stipe stains blue when injured, and its basidiospores are broader than those of Bu. pseudoroseoflavus [68]. Both stipe and context of Bu. roseogriseus and Bu. primiregius turn blue when injured, and have broader basidiospores, Q = (1.95) 2.20–2.42 (2.57) and Q = 3.5, respectively [32,56]. The pores of Bu. regius are unchanging to blue when bruised; the stipe is usually ventricose when young, showing at the base rare faintly reddish or purplish spots, with basidiospores weakly dextrinoid [69]. Butyriboletus fuscoroseus is characterized by its brown-pink, reddish brown, or purplish brown pileus, decurrent hymenophore, stipe staining blue when bruised or cut, and the narrow basidiospores [56]. Phylogenetically, Bu. pseudoroseoflavus is similar to Bu. abieticola. However, Bu. abieticola is characterized by a light rose-colored pileus, with tan-colored spots interspersed, a white context, a hymenium dextrinoid, and hyaline spiral incrustations on most hyphae [70]. Reference Table 2 provides the critical characteristics distinguishing Bu. pseudoroseoflavus from other species in China.

Table 2.

Morphological comparisons of Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus sp. nov. and Butyriboletus subregius sp. nov. with other Butyriboletus spp. reported in China.

| Species | Pileus | Context | Hymenophore | Stipe | Spores | Cystidia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyriboletus huangnianlaii | Surface dry, finely tomentose, brown to reddish brown | Yellowish to yellow, changing blue quickly when injured | Adnate or slightly depressed, changing blue quickly when injured | Stipitipellis, fertile hymeniform, fusiform, or subfusiform terminal cells | (7.0) 7.5–10.5 (11.0) × 3.0–4.0 μm, olive-brown to yellowish brown | Fusiform or subfusiform |

| Bu. pseudospeciosus | Purplish tint, staining dark blue quickly when bruised | Yellowish, staining blue to grayish blue promptly when injured | Adnate, rapidly bluing when bruised | Stipitipellis consisting of tufts of lageniform caulocystidia | 9.0–11.0 (12.0) × 3.5–4.0 μm | Narrowly lageniform to lageniform |

| Bu. roseoflavus | Pinkish to purplish red or rose-red | Yellowish or light yellow, turning blue slowly or unchanging when bruised | Adnate, staining blue quickly when hurt | Stipe trama composed of parallel hyphae | 9.0–12.0 (13.0) × 3.0–4.0 μm | Narrowly lageniform to lageniform |

| Bu. sanicibus | Dull brown | Pale yellow, usually turning blue when cut | Depressed, bruising blue | – | 11.0–15.0 × 4.0–5.0 μm | Fusoid-ventricose |

| Bu. subregius | Pastel pink | Yellowish green, turning blue when cut | weakly decurrent, covered with a layer of whitish mycelium when young, surface yellowish green | Stipitipellis fertile, hymeniform, caulocystidia narrowly lageniform, caulobasidia subclavate, with yellowish intracellular pigments. | (10.0) 11.1–11.5 (13.0) × (3.0) 4.0–4.2 (5.0) μm | narrowly lageniform |

| Bu. yicibus | Covered with fibrillose squamules, ochreous, brown to dark brown | Nearly white, staining light blue very slowly when injured | Adnate, degrading bluish slowly when injured | Stipitipellis consisting of tufts of lageniform caulocystidia | (11.0) 13.0–15.0 (16.0) × 4.0–5.0 (5.5) μm | Narrowly lageniform to lageniform |

| Bu. pseudoroseoflavus | Tomentose, pink to greyish rose | Light yellow, unchanging in color when injured. | Adnate to decurrent, staining blue when bruised | Stipitipellis hymeniform, with terminal inflated cells | (7.0) 10.2–11.0 (16.0) × (2.0) 3.1–3.7 (4.0) μm | Narrowly lageniform |

Butyriboletus subregius Yang Wang, Bo Zhang & Yu Li, sp. nov.

Mycobank No.: 842517.

Figure 5d, Figure 7c and Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Butyriboletus subregius. (a) Pleurocystidia; (b) Cheilocystidia; (c) Pileipellis; (d) Basidiospores. (e) Pleurocystidia and basidia. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Etymology.:“sub” means “near,” named because it is similar to B. regius.

Holotypus: China. Jilin Province, Jian city, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, 125°34′33″ E, 40°52′7″ N, under Quercus mongolica, on dark-brown soil, alt. 1050 m, 7 July 2020, Yong-Lan Tuo 95 (HMJAU 60200!).

Basidiomata middle to large. Pileus 7.0–13.0 cm in diameter, hemispherical or broadly hemispherical at maturity, with distinctly appendiculate margin initially, surface dry, covered with weak or distinct tomentum, pastel pink (11A4–5), context yellowish green (30A6), turning blue when cut. Hymenophore weakly decurrent, covered with a layer of whitish mycelium (1A1) when young, surface yellowish green (29A6), bluing when bruised, pores angular to nearly round, ca. 4–5/mm; tubes concolorous with hymenophore surface, about 1.1 cm long, turning blue when cut. Stipe 11.0–14.5 × 4.4–5.0 cm, subcylindrical or enlarged downwards, yellowish green (29A6) at maturity, covered with pastel red stains when young, upper 2/3 portion covered with yellowish green (29A6) reticulation, staining blue when bruised, context yellowish green (30A6), changing weakly to blue when cut.

Basidiospores (60/2/2) (10.0) 11.1–11.3–11.5 (13.0) × (3.0) 4.0–4.1–4.2 (5.0) μm, Q = (2.22) 2.40–3.00 (4.00), Qm = 2.76 ± 0.31, subfusoid to subcylindrical, inequilateral with a suprahilar depression in side view, brownish yellow in 5% KOH, smooth. Basidia 21.0–36.0 × 8.0–12.5 μm, clavate, 2– and 4–spored. Hymenophoral trama boletoid, composed of hyphae 4–7 μm in diameter. Pleurocystidia 36.3–56.7 × 7.0–14.6 μm, narrowly lageniform, thin-walled, yellowish in 5% KOH. Cheilocystidia 22.0–50.5 × 5.5–12.4 μm, narrowly lageniform. Pileipellis a trichodermium, composed of filamentous hyphae, 3.0–6.5 μm wide. Stipitipellis fertile, hymeniform, caulocystidia 23.0–43.5 × 9.0–12.5 μm, narrowly lageniform, caulobasidia 17.2–32.0 × 6.2–8.0 μm, subclavate, with yellowish intracellular pigments. Clamp connections not observed.

Habitat: solitary or scattered on a dark-brown soil of Quercus mongolica forest.

Known distribution: currently, only known from Jilin province, China.

Additional collection examined: China. Jilin Province, Jian city, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, under Quercus mongolica, on dark-brown soil, alt. 1050 m, 10 August 2019, Yong-Lan Tuo 198 (HMJAU 60201).

Notes: Butyriboletus subregius is characterized by a pastel pink pileus, a yellowish green stipe covered with reticulation of the same color and staining blue when the hymenophore and stipe are bruised. Morphologically and phylogenetically, Bu. subregius resembles Bu. autumniregius, Bu. primiregius, Bu. querciregius, Bu. regius and Bu. fuscoroseus. However, Bu. autumniregius is distinguished by its autumn fruiting season, a stipe that commonly has dark red stains toward the base, and longer spores with a larger Q value [33]; Bu. primiregius is characterized by its late spring season, and a pileus tending to dingy olive-brown as it ages or exposed in sunlight [33]; Bu. querciregius differs from Bu. subregius in its mycorrhizal host, the dull color of a pileus, relatively longer spores with larger Q value [33]; Bu. regius is different from Bu. subregius in its pileus covered with distinct scales with aging, a context usually not bluing when cut, and spores longer with larger Q value [69]. Butyriboletus fuscoroseus is different from Bu. subregius in its brown-pink, reddish brown, or purplish-brown pileus, fine reticulation covered only on the upper half of stipe and context of stipe strongly bluing when cut [56]. Reference Table 2 provides the critical characteristics distinguishing Bu. subregius from other species in China.

Tengioboletus subglutinosus Yang Wang, Bo Zhang & Yu Li, sp. nov.

Mycobank No.: 842168.

Figure 5f, Figure 7e,f and Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Tengioboletus subglutinosus. (a) Pileipellis; (b) Stipitipellis; (c) Basidiospores; (d) Cheilocystidia; (e,f) Pleurocystidia and basidia. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Etymology: “sub” means “near,” named because it is similar to T. glutinosus.

Holotypus: China. Jilin Province, Jian city, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, 125°34′33″ E, 40°52′7″ N, under Quercus mongolica, on dark-brown soil, alt. 650 m, 6 August 2020, Y. L. Tuo 293 (HMJAU 59035!).

Basidiomata medium to large. Pileus 6.5–9.0 cm in diameter, hemispherical to applanate, surface brownish yellow (5C8) to yellowish brown (5D8), glabrous, viscid when wet, context deep yellow (4A8), 0.6–1.5 cm thick, color unchanging when cut; hymenophore sinuate to decurrent; tubes up to 1.3 cm long, vivid yellow (3A8), changing to indistinct blue erratically or unchanging color when cut; hymenophore surface concolorous with tubes or olive yellow (3C8), staining blue when bruised; pores angular, ca. 2–3/mm. Stipe 7.2–16.0 × 1.4–2.2 cm, central, clavate to subcylindrical, solid, sometimes tapered downwards, surface concolorous with pileus surface, covered with fine reticulation at apex, context deep yellow (4A8), color unchanging when cut; basal mycelium yellow (3B8).

Basidiospores (60/2/1) (10.0) 11.5–11.7–11.9 (13.0) × (4.0) 4.2–4.3–4.4 (6.0) μm [Q = (1.70) 2.00–3.17 (3.25) 2.75 ± 0.3], elongate ellipsoid and inequilateral in side view, with distinctly suprahilar depression; greenish yellow (1A8) in 5% KOH, smooth. Hymenophoral trama of the intermediate type between phylloporoid and boletoid types. Basidia 19.0–42.0 × 6.0–13.0 μm, clavate, 2- and 4-spored, hyaline in 5% KOH. Pleurocystidia scattered, 45.0–65.0 × 9.0–15.0 μm, fusoid-ventricose to broadly fusoid-ventricose, with subacute apex or long beak, thin-walled. Cheilocystidia 36.0–50.0 × 7.5–10.5 μm, similar to pleurocystidia in shape. Pileipellis an interwoven ixotrichodermium, with inflated terminal cells 28.5–57.0 × 15.0–23.0 μm. Stipitipellis fertile, hymeniform, with subglobose to globose terminal cells, and scattered clavate basidia.

Habitat: solitary or scattered on a dark-brown soil of Quercus mongolica forest.

Known distribution: currently, only known from Jilin province, China.

Additional collections examined: China. Jilin Province, Jian city, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, under Quercus mongolica, on dark-brown soil, alt. 900 m, 6 August 2020, Yong-Lan Tuo 286 (HMJAU 59034); alt. 750 m, 11 August 2020, Yong-Lan Tuo 344 (HMJAU 59036); alt. 650 m, 23 August 2020, Yong-Lan Tuo 471 (HMJAU 59037).

Notes: Tengioboletus subglutinosus is characterized by a hymenophore surface staining blue when bruised, a pileipellis in the form of an ixotrichodermium, with inflated or clavated terminal cells. Morphologically and phylogenetically, T. subglutinosus is similar to T. glutinosus. However, T. subglutinosus is different due to its hymenophoral surface staining blue when bruised, a hymenophore sinuate to decurrent, a stipe with reticulations at the apex, and narrower spores [5]. Tengioboletus fujianensis differs from T. subglutinosus in its hymenophoral surface staining brown when bruised, prominently reticulation nearly to the stipe base and hymenophoral trama boletoid [34]. Basidiomata of T. reticulatus show a distinct olive-brown, brown-to dark-brown pileus, shorter hymenophore of unchanging color when bruised, a distinct reticulation covering stipe, and a pileipellis trichodermium, not ixotrichodermium [5].

Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus Yang Wang, Bo Zhang & Yu Li, sp. nov.

Mycobank No.: 842518.

Figure 5a–c, Figure 7a,b and Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus. (a) Basidiospores; (b) Basidia; (c) Pileipellis. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Etymology: “lacrymibasidiatus” means most of its basidia seem lacrymoid.

Holotypus: China. Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region: Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinyuan county, 84°31′20″ E, 43°15′43″ N, under Pinus schrenkiana, on light grayish brown loess, alt. 1899 m, 3 August 2021, W3194 (HMJAU 60202!).

Basidiomata medium. Pileus 4.1–8.2 cm in diameter, hemispherical then applanate, surface oak brown (5D6) when young, brownish orange (6C6) at maturity, weakly tomentose, context yellowish white (1A2), 0.4–0.9 cm thick, turning blue when cut. Hymenophore adnexed, surface tomato red (8C8) when young, brick red (7D7) at maturity, bluing quickly when injured, pores angular, ca. 1–3/mm; tubes up to 1.3 cm long, sulfur yellow (1A5), bluing promptly when cut. Stipe 7.2–7.4 × 1.7–2.0 cm, subcylindrical, relatively slender at middle part or attenuate downwards, surface red (10A6) when young, finely longitudinally reticulated over the apex, color of surface fading to yellow and covered with distinct squamules at the middle part in ages, context pastel green (30A4), turning blue when cut; basal mycelium white.

Basidiospores (60/2/2) (11.6) 14.5–14.7–15 (17.0) × (6.7) 7.7–7.8–7.9 (9.0) μm, Q = 1.5–2.1, Qm = 1.9 ± 0.1, subamygdaloid to broadly ellipsoid, brown in 5% KOH, smooth, neither amyloid nor dextrinoid. Hymenophoral trama boletoid type, composed of 2.0–16.5 μm wide hyphae, amyloid. Basidia 20.8–38.5 × 13.0–20.1 μm, lacrymoid, 2– and 4–spored, hyaline in 5% KOH. Pleurocystidia and cheilocystidia not observed. Pileipellis a trichodermium, composed of 5.0–9.5 μm wide, yellowish brown, inamyloid hyphae. Stipitipellis hymeniderm, terminal cells inflated, 25.8–61.2 × 12.0–15.5 μm. Hyphae of the flesh in the stipe base amyloid in Melzer’s reagent. Clamp connections not observed.

Habitat: solitary or scattered on a black loam soil of Salix spp. and Populus spp. mixed forest or a light grayish brown loess of Pinus schrenkiana forest.

Known distribution: currently, only known from Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China.

Additional collection examined: China. Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region: Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Zhaosu County, 80°42′30″ E, 42°59′37″ N, under river valley with presence of Salix spp. and Populus spp., on black loam soil, alt. 1697 m, 6 August 2021, W3229 (HMJAU 60203).

Notes: Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus is characterized by its oak brown to brownish orange pileus, the context staining blue when injured, and inamyloid basidiospores. Morphologically, S. lacrymibasidiatus is related to S. luridus (Schaeff.) Murrill, S. mendax (Simonini & Vizzini) Vizzini, Simonini & Gelardi, S. queletii (Schulzer) Vizzini, Simonini & Gelardi, and S. subamygdalinus Kuan Zhao & Zhu L. Yang. S. luridus is characterized by its prominent reticulation on the stipe and smaller basidiospores [71]; S. mendax is different from S. lacrymibasidiatus in its promptly bluing when pileus bruised, value of Q larger, and basidia clavate [13]; S. queletii can be distinguished from S. lacrymibasidiatus by its stipe wholly covered with fine granulation without reticulation, basidia clavate [72]; S. subamygdalinus is characterized by its basidia clavate [5]. Phylogenetically, S. lacrymibasidiatus is related to S. comptus. However, S. comptus differs from S. lacrymibasidiatus in its stipe surface staining blue when bruised, and smaller spores [71]. Among the other morphologically allied boletes, S. adalgisae (Marsico & Musumeci) N. Schwab [73], S. austrinus (Singer) Murrill [74], S. gabretae (Pilát) Blanco-Dios [75], S. luridiceps Murrill [76], and S. subvelutipes (Peck) Murrill. [77], none of them could represent a possible concurrent of S. lacrymibasidiatus.

A key to worldwide species of Tengioboletus:

| 1. Pores changing color when bruised | 2 |

| 1. Pores unchanging color when bruised | 3 |

| 2. Pores staining blue when bruised, pileipellis an ixotrichodermium | T. subglutinosus |

| 2. Pores staining brown when bruised, pileipellis an trichodermium | T. fujianensis |

| 3. Stipe covered with distinct reticulations, basidiospores larger, 12.0–14.5 × 4.5–6.0 μm, pileipellis an trichodermium | T. reticulatus |

| 3. Stipe nearly glabrous, basidiospores 10.0–12.0 × 3.5–4.5 μm, pileipellis, an ixotrichodermium | T. glutinosus |

A key to worldwide species of Suillellus s.str.:

| 1. Basidiospores usually longer than 15 μm | 2 |

| 1. Basidiospores shorter than or equal to 15 μm | 4 |

| 2. Stipe covered with pruinose or granulose, but without any trace of reticulation | S. amygdalinus |

| 2. Stipe covered with reticulation | 3 |

| 3. Basidia lacrymoid, Q = 1.5–2.1 | S. lacrymibasidiatus |

| 3. Basidia clavate, Q = 2.0–2.6 | S. subamygdalinus |

| 4. Surface of stipe rough, but without reticulation | 5 |

| 4. Stipe covered with reticulation | 6 |

| 5. Stipe covered with distinct pruinose, basidiospores less than 14 μm, basidia broad clavate | S. adonis |

| 5. Stipe covered with reddish to brown granules, basidiospores can be longer than 14 μm, hymenophoral basidia clavate | S. queletii |

| 6. Stipe covered with prominent, red to orange reticulation. Basidiospores 11–14 × 4.5–6 μm | S. luridus |

| 6. Stipe with indistinctly or finely reticulation, usually distributed erratically | 7 |

| 7. Q value higher than 2.6 | S. mendax |

| 7. Q value less than or equal to 2.6 | 8 |

| 8. Basidiospores dextrinoid, Q value can reach 2.6, reticulation yellow and fine at the upper portion of stipe | S. atlanticus |

| 8. Q value less than or equal to 2.2, pores red to orange red, stipe covered with very fine yellow, pale orange, orange, reddish orange, or pale red granules | S. comptus |

4. Discussion

In this study, four new species, Butyriboletus pseudoroseoflavus, Butyriboletus subregius, Tengioboletus subglutinosus, and Suillellus lacrymibasidiatus, were discovered in northern China based on morphological studies and phylogenetic analyses.

Seven species of Butyriboletus were previously reported in China, and all of them were collected from tropical and subtropical regions of China. The two new species of Butyriboletus we proposed here are the first reports of this genus in northern China. Moreover, according to Arora et al. [33], the species diversity of the genus should be more abundant in temperate climes than tropical, subtropical, or boreal ones. Based on this, we presume that northern China may be a species diversity hotspot of Butyriboletus waiting to be explored further.

Butyriboletus subregius is easily confused with Bu. autumniregius, Bu. primiregius, Bu. querciregius, and Bu. regius, morphologically. The primary distinguishing characteristics are the fruiting time and different ecological niches. According to Queiroz [78], these differences mean that the features formerly treated as secondary species criteria are relevant to species delimitation, to the extent that they provide evidence of a lineage separation. Although one ITS sequence of Bu. loyo (Phillippi) Mikšík, was uploaded to the GeneBank [79], the authors did not give a detailed morphological description to prove identification accuracy, so it was excluded from the current phylogeny. However, Bu. loyo is unique within this genus, given its combined morphological characteristics of being equilateral in profile and having red-brown basidiospores and a viscid pileus.

Due to the different color of the hymenophore surface and tubes and the usually vivid red color of basidiomata, Farid et al. [19], Bozok et al. [80], and Biketova et al. [37] all recommended Exsudoporus as a genus separate from Butyriboletus, including B. floridanus (Singer) G. Wu, Kuan Zhao & Zhu L. Yang, B. frostii (J.L. Russell) G. Wu, Kuan Zhao, & Zhu L. Yang, and E. permagnificus (Pöder) Vizzini, Simonini, & Gelard. However, only the result of Farid et al. [19] showed that the B. subsplendidus (W.F. Chiu) Kuan Zhao, G. Wu, & Zhu L. Yang clade has affinity with other Butyriboletus. Our phylogram accords with the findings of Chai [28] and Biketova et al. [37] that B. subsplendidus is a sister to the Exsudoporus clade. We agree with Biketova et al. [37] that Exsudoporus should be elevated to genus status, and B. subsplendidus and B. hainanensis N.K. Zeng, Zhi Q. Liang, & S. Jiang should separate from Butyriboletus and represent two distinct genera, as their apparently different characteristics from other species of Butyriboletus.

Tengioboletus is a small genus, with only three species previously reported in southern China. Tengioboletus reticulatus was the first species of the genus collected at Liaoning province in northeastern China [81]. In our study, one new species, T. subglutinosus, was also collected at Jilin province in northeastern China. This means a geographical extension of Tengioboletus into temperate zones, which may also indicate a potentially wide distribution, given that their previously known main distribution was subtropical and tropical China. Our study showed that sequences of Tengioboletus formed an independent clade, which corresponded to the findings of Wu et al. [5] and supported Tengioboletus as a separate genus. As found by Wu et al. [5], Porphyrellus E.-J. Gilbert is a polyphyletic genus in the phylogram (Figure 1); it formed two clades; one clade named “Porphyrellus?” is a sister to Strobilomyces Berk., as was implied by Han et al. [82]. Clarification of the relationships among the genera will require additional specimens and future studies.

Recently, many genera were merged or erected in boletes as part of the development of molecular technology. Wu et al. [5] treated Neoboletus Gelardi, Simonini, & Vizzini as synonymized with Sutorius Halling, Nuhn, & N.A. Fechner, based on molecular data. However, Chai et al. [28] studied the morphological characteristics and reconstructed phylogenetic trees of Neoboletus, Sutorius, Costatisporus T.W. Henkel & M.E. Sm., and Caloboletus Vizzini. They considered that Neoboletus do not belong to Sutorius. Our phylogenetic analyses (Figure 3) confirmed their results.

Rubroboletus Kuan Zhao & Zhu L. Yang, Neoboletus, Sutorius, and Lanmaoa G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang shares some characteristics with Suillellus, such as the orange-red surface of the hymenophore and the bluing color change. Nevertheless, none of them has the amyloid hyphae of the context [5,25,83,84,85]. In contrast, Rubroboletus species have a vivid or dark red pileus with rose-to-red reticulation, and the stipes of species of Neoboletus usually have fine dots but never reticulation. The basidiomata of Sutorius always have a dull color and a reddish color change [28,86]; the hymenophore of Lanmaoa is thin, with a thickness about 1/3–1/5 times that of the pileal context at the position halfway to the pileus center.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Zheng-Xiang Qi, Xin-Ya Yang, and Ya-Jie Liu of the Engineering Research Center of Edible and Medicinal Fungi, Ministry of Education, Jilin Agricultural University for their help in the experiment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof8030218/s1, File S1: Tengioboletus matrix, File S2: Butyriboletus matrix, File S3: Suillellus multigene matrix, File S4: Suillellus ITS matrix.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z. and Y.L.; Methodology, Y.W.; Software, X.-M.W. and J.W.; Investigation, Y.W., Y.-L.T., and G.R.; Resources, Y.W., Y.-L.T., G.R., Z.-H.Z., D.-M.W. and N.G.; Data Curation, B.Z. and Y.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, B.Z. and D.D.; Visualization, Y.W.; Supervision, B.Z.; Project Administration, B.Z. and Y.L.; Funding Acquisition, B.Z. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Production and Construction Corps (No.2021AB004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31970020), the Research of the Degradation Mechanism of Macrofungi Metabolites on Wetland Water Pollutants (20190201256JC), and Key Projects of Jiangxi Province Key R&D Plan (20212BBF61002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data relevant to this research can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; https://www.mycobank.org/; https://www.treebase.org/treebase-web/home.html, accessed on 15 January 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chevallier F.F. Flore Générale des Environs de Paris. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. Available online: https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/idurl/1/11834.

- 2.Zhang M. Ph.D. Thesis. South China University of Technology; Guangzhou, China: 2016. Molecular Phylogenetic Studies on the Family Boletaceae in Southern China, and Taxonomic Study on the Genus Aureoboletus in China. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y., Li T.H., Yang Z.L., Bau T., Dai Y.C. Atlas of Chinese Macrofungal Resources. Central Plains Farmers Press; Zhengzhou, China: 2016. pp. 1068–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman M.D., Claveria V., Miguel A.M. A revision of the descriptions of ectomycorrhizas published since 1961. Mycol. Res. 2005;109:1063–1104. doi: 10.1017/S0953756205003564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu G., Li Y.C., Zhu X.T., Zhao K., Han L.H., Cui Y.Y., Li F., Xu J.P., Yang Z.L. One hundred noteworthy boletes from China. Fungal Divers. 2016;81:25–188. doi: 10.1007/s13225-016-0375-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z.L., Wu G., Li Y.C., Wang X.H., Cai Q. Common Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms of Southwestern China. Science Press; Beijing, China: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murrill W.A. The Boletaceae of North America—I. Mycologia. 1909;1:4–18. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1909.12020569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith A.H., Thiers H.D. Boletes of Michigan. The University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor, MI, USA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer R., Williams R. Some boletes from Florida. Mycologia. 1992;84:724–728. doi: 10.2307/3760382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baroni T.J. Boletus aurantiosplendens sp. nov. from the southern Appalachian Mountains with notes on Pulveroboletus auriflammeus, Pulveroboletus melleouluteus and Boletus auripes. Bull. Buffalo Soc. Nat. Sci. 1998;36:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baroni T.J., Bessette A.E., Roody W.C. Boletus patrioticus—A new species from the eastern United States. Bull. Buffalo Soc. Nat. Sci. 1998;36:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farid A., Gelardi M., Angelini C., Franck A., Costanzo F., Kaminsky L., Ercole E., Baroni T., White A., Garey J. Phylloporus and Phylloboletellus are no longer alone: Phylloporopsis gen. nov. (Boletaceae), a new smooth-spored lamellate genus to accommodate the American species Phylloporus Boletinoides. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2018;2:341. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2018.02.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vizzini A., Simonini G., Ercole E., Voyron S. Boletus mendax, a new species of Boletus sect. Luridi from Italy and insights on the B. luridus complex. Mycol. Prog. 2014;13:95–109. doi: 10.1007/s11557-013-0896-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortiz-Santana B., Roody W.C., Both E.E. A new arenicolous Boletus from the Gulf Coast of northern Florida. Mycotaxon. 2009;107:243–247. doi: 10.5248/107.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortiz-Santana B., Bessette A.E., McConnell O.L. Boletus durhamensis sp. nov. from North Carolina. Mycotaxon. 2016;131:703–715. doi: 10.5248/131.703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank J., Siegel N., Schwarz C., Araki B., Vellinga E. Xerocomellus (Boletaceae) in western North America. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2020;6:265. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2020.06.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crous P., Wingfield M., Lombard L., Roets F., Swart W., Alvarado P., Carnegie A., Moreno G., Luangsaard J., Thangavel R. Fungal Planet description sheets: 951–1041. Persoonia. 2019;43:223. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farid A., Franck A.R., Bolin J., Garey J.R. Expansion of the genus Imleria in North America to include Imleria floridana, sp. nov., and Imleria pallida, comb. nov. Mycologia. 2020;112:423–437. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2019.1685359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farid A., Bessette A.R., Bolin J.A., Kudzma L.V., Franck A.R., Garey J.R. Investigations in the boletes (Boletaceae) of southeastern USA: Four novel species and three novel combinations. Mycosphere. 2021;12:1038–1076. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/12/1/12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor J.W., Jacobson D.J., Kroken S., Kasuga T., Geiser D.M., Hibbett D.S., Fisher M.C. Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000;31:21–32. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuhn M.E., Binder M., Taylor A.F., Halling R.E., Hibbett D.S. Phylogenetic overview of the Boletineae. Fungal Biol. 2013;117:479–511. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu G., Feng B., Xu J.P., Zhu X.T., Li Y.C., Zeng N.K., Hosen M.I., Yang Z.L. Molecular phylogenetic analyses redefine seven major clades and reveal 22 new generic clades in the fungal family Boletaceae. Fungal Divers. 2014;69:93–115. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0283-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson A.W., Binder M., Hibbett D.S. Diversity and evolution of ectomycorrhizal host associations in the Sclerodermatineae (Boletales, Basidiomycota) New Phytol. 2012;194:1079–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu G., Miyauchi S., Morin E., Kuo A., Drula E., Varga T., Kohler A., Feng B., Cao Y., Lipzen A. Evolutionary innovations through gain and loss of genes in the ectomycorrhizal Boletales. New Phytol. 2022;233:1383–1400. doi: 10.1111/nph.17858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao K., Wu G., Yang Z.L. A new genus, Rubroboletus, to accommodate Boletus sinicus and its allies. Phytotaxa. 2014;188:61–77. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.188.2.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X.T., Wu G., Zhao K., Halling R.E., Yang Z.L. Hourangia, a new genus of Boletaceae to accommodate Xerocomus cheoi and its allied species. Mycol. Prog. 2015;14:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11557-015-1060-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu G., Zhao K., Li Y.C., Zeng N.K., Feng B., Halling R.E., Yang Z.L. Four new genera of the fungal family Boletaceae. Fungal Divers. 2016;81:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s13225-015-0322-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chai H., Liang Z.Q., Xue R., Jiang S., Luo S.H., Wang Y., Wu L.L., Tang L.P., Chen Y., Hong D. New and noteworthy boletes from subtropical and tropical China. MycoKeys. 2019;46:55. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.46.31470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M.X., Wu G., Yang Z.L. Four New Species of Hemileccinum (Xerocomoideae, Boletaceae) from Southwestern China. J. Fungi. 2021;7:823. doi: 10.3390/jof7100823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelardi M., Vizzini A., Ercole E., Horak E., Ming Z., Li T.H. Circumscription and taxonomic arrangement of Nigroboletus roseonigrescens gen. et sp. nov., a new member of Boletaceae from tropical South–Eastern China. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0134295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Y.Y., Feng B., Wu G., Xu J.P., Yang Z.L. Porcini mushrooms (Boletus sect. Boletus) from China. Fungal Divers. 2016;81:189–212. doi: 10.1007/s13225-015-0336-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang Z.Q., An D.Y., Juang S., Su M.S., Zeng N.K. Butyriboletus hainanensis (Boletaceae, Boletales), a new species from tropical China. Phytotaxa. 2016;267:256–262. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.267.4.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora D., Frank J.L. Clarifying the butter Boletes: A new genus, Butyriboletus, is established to accommodate Boletus sect. Appendiculati, and six new species are described. Mycologia. 2014;106:464–480. doi: 10.3852/13-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng N.K., Chai H., Jiang S., Xue R., Wang Y., Hong D., Liang Z.Q. Retiboletus nigrogriseus and Tengioboletus fujianensis, two new boletes from the south of China. Phytotaxa. 2018;367:45–54. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.367.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornerup A., Wanscher J.H. In: Methuen Handbook of Colour. 3rd ed. Pavey D., editor. Eyre Methuen; London, UK: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Imler L. Recherches sur les bolets. Bull. Soc. Mycol. Fr. 1950;66:177–203. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biketova A.Y., Gelardi M., Smith M.E., Simonini G., Healy R.A., Taneyama Y., Vasquez G., Kovács A., Nagy L.G., Wasser S.P., et al. Reappraisal of the Genus Exsudoporus (Boletaceae) Worldwide Based on Multi-Gene Phylogeny, Morphology and Biogeography, and Insights on Amoenoboletus. J. Fungi. 2022;8:101. doi: 10.3390/jof8020101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X.T., Li Y.C., Wu G., Feng B., Zhao K., Gelardi M., Kost G.W., Yang Z.L. The genus Imleria (Boletaceae) in East Asia. Phytotaxa. 2014;191:81–98. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.191.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guide Methods Appl. 1990;18:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cubeta M., Echandi E., Abernethy T., Vilgalys R. Characterization of anastomosis groups of binucleate Rhizoctonia species using restriction analysis of an amplified ribosomal RNA gene. Phytopathology. 1991;81:1395–1400. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-81-1395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vilgalys R., Hester M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:4238–4246. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rehner S.A., Buckley E. A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-α sequences: Evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia. 2005;97:84–98. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.97.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang M., Li T.H., Song B. Two new species of Chalciporus (Boletaceae) from southern China revealed by morphological characters and molecular data. Phytotaxa. 2017;327:47–56. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.327.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo M., Ortiz-Santana B. Revision of leccinoid fungi, with emphasis on North American taxa, based on molecular and morphological data. Mycologia. 2020;112:197–211. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2019.1685351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall T. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. doi: 10.14601/PHYTOPATHOL_MEDITERR-14998U1.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lanfear R., Frandsen P.B., Wright A.M., Senfeld T., Calcott B. PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:772–773. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B.Q., Wong T.K., Von Haeseler A., Jermiin L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen L.T., Schmidt H.A., Von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ronquist F., Teslenko M., Van Der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Höhna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Binder M., Hibbett D.S. Molecular systematics and biological diversification of Boletales. Mycologia. 2006;98:971–981. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feng B., Xu J.P., Wu G., Zeng N.K., Li Y.C., Tolgor B., Kost G.W., Yang Z.L. DNA sequence analyses reveal abundant diversity, endemism and evidence for Asian origin of the porcini mushrooms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Binder M., Bresinsky A. Retiboletus, a new genus for a species-complex in the Boletaceae producing retipolides. Feddes Repert. Z. Bot. Taxon. Geobot. 2002;113:30–40. doi: 10.1002/1522-239X(200205)113:1/2<30::AID-FEDR30>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao K., Wu G., Halling R.E., Yang Z.L. Three new combinations of Butyriboletus (Boletaceae) Phytotaxa. 2015;234:51–62. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.234.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao K., Wu G., Feng B., Yang Z.L. Molecular phylogeny of Caloboletus (Boletaceae) and a new species in East Asia. Mycol. Prog. 2014;13:1127–1136. doi: 10.1007/s11557-014-1001-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halling R.E., Nuhn M., Fechner N.A., Osmundson T.W., Soytong K., Arora D., Hibbett D.S., Binder M. Sutorius: A new genus for Boletus eximius. Mycologia. 2012;104:951–961. doi: 10.3852/11-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Šutara J., Janda V., Kříž M., Graca M., Kolařík M. Contribution to the study of genus Boletus, section Appendiculati: Boletus roseogriseus sp. nov. and neotypification of Boletus fuscoroseus Smotl. Czech Mycol. 2014;66:1–37. doi: 10.33585/cmy.66101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y.C., Ortiz-Santana B., Zeng N.K., Feng B., Yang Z.L. Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Veloporphyrellus. Mycologia. 2014;106:291–306. doi: 10.3852/106.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y.C., Feng B., Yang Z.L. Zangia, a new genus of Boletaceae supported by molecular and morphological evidence. Fungal Divers. 2011;49:125–143. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0096-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krpata D., Peintner U., Langer I., Fitz W.J., Schweiger P. Ectomycorrhizal communities associated with Populus tremula growing on a heavy metal contaminated site. Mycol. Res. 2008;112:1069–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osmundson T.W., Robert V.A., Schoch C.L., Baker L.J., Smith A., Robich G., Mizzan L., Garbelotto M.M. Filling gaps in biodiversity knowledge for macrofungi: Contributions and assessment of an herbarium collection DNA barcode sequencing project. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iotti M., Barbieri E., Stocchi V., Zambonelli A. Morphological and molecular characterisation of mycelia of ectomycorrhizal fungi in pure culture. Fungal Divers. 2005;19:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nygren C.M., Edqvist J., Elfstrand M., Heller G., Taylor A.F. Detection of extracellular protease activity in different species and genera of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza. 2007;17:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s00572-006-0100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin M.P., Raidl S. The taxonomic position of Rhizopogon melanogastroides (Boletales) Mycotaxon. 2002;84:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith M.E., Douhan G.W., Rizzo D.M. Ectomycorrhizal community structure in a xeric Quercus woodland based on rDNA sequence analysis of sporocarps and pooled roots. New Phytol. 2007;174:847–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mello A., Ghignone S., Vizzini A., Sechi C., Ruiu P., Bonfante P. ITS primers for the identification of marketable boletes. J. Biotechnol. 2006;121:318–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palmer J.M., Lindner D.L., Volk T.J. Ectomycorrhizal characterization of an American chestnut (Castanea dentata)-dominated community in Western Wisconsin. Mycorrhiza. 2008;19:27–36. doi: 10.1007/s00572-008-0200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li H., Wei H., Peng H., Ding H., Wang L., He L., Fu L. Boletus roseoflavus, a new species of Boletus in section Appendiculati from China. Mycol. Prog. 2014;13:21–31. doi: 10.1007/s11557-013-0888-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takahashi H., Taneyama Y., Degawa Y. Notes on the boletes of Japan 1. Four new species of the genus Boletus from central Honshu, Japan. Mycoscience. 2013;54:458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Janda V., Kříž M., Kolařík M. Butyriboletus regius and Butyriboletus fechtneri: Typification of two well-known species. Czech Mycol. 2019;71:1–32. doi: 10.33585/cmy.71101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thiers H.D. California Mushrooms—A Field Guide to the Boletes. Hafner Press; New York, NY, USA: 1975. p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muñoz J.A. Fungi Europaei 2. Candusso Editrice; Bardolino, Italy: 2005. Boletus s.l. (excl. Xerocomus) pp. 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heykoop M. Morphology and taxonomy of Boletus queletii var. discolor, a rare bolete resembling Boletus erythropus. Mycotaxon. 1995;56:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marsico O., Musumeci E. Boletus adalgisae sp. nov. Boll. Assoc. Micol. Ecol. Romana. 2011;27:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seaver F.J., John N.C., Murrill W.A., George L.Z., Fred W., Singer R. Notes and Brief Articles. Mycologia. 1945;37:792–799. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1945.12024031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pilát A. Boletus gabretae sp. nov. bohemica ex affinitate Boleti junguillei (Quél.) Boud. Czech Mycol. 1968;22:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murill W.A. More Florida fungi. Lloydia. 1946;8:263–290. [Google Scholar]

- 77.New York State Museum . Bulletin of the New York State Museum. Volume 2. University of the State of New York; New York, NY, USA: 1889. pp. 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Queiroz K. Species concepts and species delimitation. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:879–886. doi: 10.1080/10635150701701083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Truong C., Mujic A.B., Healy R., Kuhar F., Furci G., Torres D., Niskanen T., Sandoval-Leiva P.A., Fernández N., Escobar J.M. How to know the fungi: Combining field inventories and DNA-barcoding to document fungal diversity. New Phytol. 2017;214:913–919. doi: 10.1111/nph.14509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bozok F., Assyov B., Taşkin H. First records of Exsudoporus permagnificus and Pulchroboletus roseoalbidus (Boletales) in association with non-native Fagaceae, with taxonomic remarks. Phytol. Balc. 2019;25:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu H.Y. Master’s Thesis. Jilin Agricultural University; Changchun, China: 2020. Taxonomy and Resource Evaluation of Boletes in Northeastern China. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muñoz J., Boletus S.L. Fungi Europaei 2. Edizioni Candusso; Alassio, Italy: 2005. (Excl. Xerocomus): Strobilomycetaceae, Gyroporaceae, Gyrodontaceae, Suillaceae, Boletaceae. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han L.H., Wu G., Horak E., Halling R., Xu J.P., Ndolo E., Sato H., Fechner N., Sharma Y., Yang Z.L. Phylogeny and species delimitation of Strobilomyces (Boletaceae), with an emphasis on the Asian species. Persoonia. 2020;44:113–139. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2020.44.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klofac W. Schlüssel zur Bestimmung von Frischfunden der europäischen Arten der Boletales mit röhrigem Hymenophor. Osterr. Z. Pilzkd. 2007;16:187–279. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vesterholt J. Funga Nordica, Agaricoid, Boletoid, Cyphelloid and Gasteroid Genera. Nordsvamp; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2012. p. 9811021. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gelardi M. Contribution to the knowledge of Chinese boletes. II: Aureoboletus thibetanus sl, Neoboletus brunneissimus, Pulveroboletus macrosporus and Retiboletus kauffmanii (Part I) Riv. Micol. Romana. 2017;102:13–30. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data relevant to this research can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; https://www.mycobank.org/; https://www.treebase.org/treebase-web/home.html, accessed on 15 January 2022.