Abstract

In plants, aldoximes per se act as defense compounds and are precursors of complex defense compounds such as cyanogenic glucosides and glucosinolates. Bacteria rarely produce aldoximes, but some are able to transform them by aldoxime dehydratase (Oxd), followed by nitrilase (NLase) or nitrile hydratase (NHase) catalyzed transformations. Oxds are often encoded together with NLases or NHases in a single operon, forming the aldoxime–nitrile pathway. Previous reviews have largely focused on the use of Oxds and NLases or NHases in organic synthesis. In contrast, the focus of this review is on the contribution of these enzymes to plant-bacteria interactions. Therefore, we summarize the substrate specificities of the enzymes for plant compounds. We also analyze the taxonomic and ecological distribution of the enzymes. In addition, we discuss their importance in selected plant symbionts. The data show that Oxds, NLases, and NHases are abundant in Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. The enzymes seem to be important for breaking through plant defenses and utilizing oximes or nitriles as nutrients. They may also contribute, e.g., to the synthesis of the phytohormone indole-3-acetic acid. We conclude that the bacterial and plant metabolism of aldoximes and nitriles may interfere in several ways. However, further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to better understand this underexplored aspect of plant-bacteria interactions.

Keywords: plant aldoxime, aldoxime-nitrile pathway, plant defense, phytohormone, indole-3-acetic acid, aldoxime dehydratase, nitrilase, nitrile hydratase, plant-bacteria interaction

1. Introduction

Oximes (RR′-C=N-OH) are metabolites that cross the boundaries between the kingdoms of life. They are widely distributed, especially in higher plants. Knowledge about plant oximes has been recently summarized [1]. Briefly, the plant oximes are largely aldoximes (R-CH=N-OH) or their methylated analogs (R-CH=N-OMe). They are derived from a few amino acids (Val, Leu, Ile, Met, Trp, Phe, and Tyr) and analogs of some of these acids. Aldoximes are intermediates in the biosynthesis of defense compounds (cyanogenic glucosides (CGs), glucosinolates (GSLs), and camalexin), but also per se have some biological activities. The functions of plant oximes are numerous, but not all of them are well understood. They include defense against pathogens and herbivores, growth control, radical scavenging, interaction with pollinators, interspecies communication, and nitrogen supply [1,2].

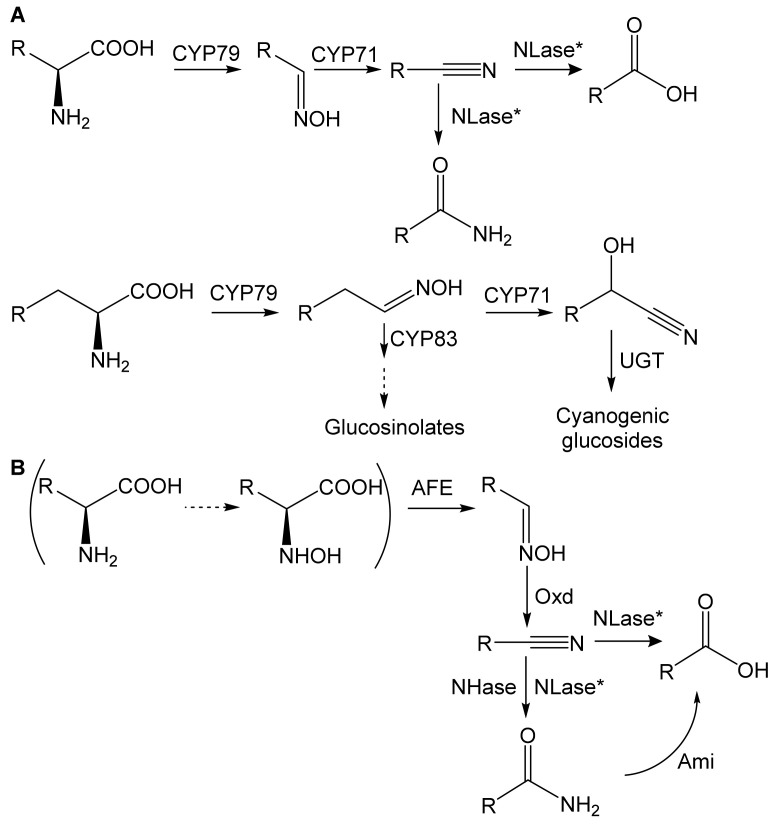

In plants, the enzymes of oxime metabolism mainly belong to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily (Figure 1A); CYP79, CYP71, and CYP83 catalyze the synthesis of aldoximes, nitriles, and precursors of GSLs, respectively [1]. Simple nitriles (R-C≡N) are hydrolyzed by nitrilase (EC 3.5.5.-; NLase) [3], and hydroxynitriles (R-C(OH)C≡N) are precursors of CGs [1].

Figure 1.

Metabolism of aldoximes in (A) plants and (B) bacteria (aldoxime-nitrile pathway). AFE, aldoxime-forming enzyme; Ami, amidase; CYP, cytochrome P450 (CYP71, CYP79, and CYP83 family); NHase, nitrile hydratase; NLase, nitrilase; Oxd, aldoxime dehydratase; UGT, UDP-glucosyl transferase; according to [1,4]. *NLase has two activities: acid- and amide-forming. The latter is usually minor. The pathway in brackets holds for R = CH2Ph. The dashed arrow means a hypothetical reaction.

Oximes are rarely produced in bacteria. An exception is Bacillus sp. OxB-1, which forms phenylacetaldoxime (PAOx) from N-hydroxy-l-phenylalanine [4]. The latter is likely a metabolite of l-Phe but the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of l-Phe is not known. The same strain is able to metabolize PAOx and other oximes (see below).

Bacterial transformation of oximes occurs via the aldoxime-nitrile pathway (ANP) (Figure 1B). Dehydration of an aldoxime to a nitrile is catalyzed by aldoxime dehydratase (Oxd; EC 4.99.1.-) [5]. Nitrile hydrolysis proceeds via two alternative pathways catalyzed by (i) NLase or (ii) nitrile hydratase (EC 4.2.1.84; NHase) and amidase (EC 3.5.1.4). Thus, the transformation of oximes in plants and bacteria involves the same metabolites (nitriles, carboxylic acids).

The industrial potential of the above enzymes has been summarized many times (e.g., [6,7,8,9]) but reviews on their natural roles are scarce. The in vivo functions of NLases were discussed by Piotrowski [3] and Howden and Preston [2], with the former work focusing on plant NLases. Aldoxime metabolism was briefly tackled in these works.

The metabolism of the phytohormone indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), which, under certain conditions, proceeds via indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx) or indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN), was reviewed previously [10]. However, the focus has been on other pathways to IAA that are more common (Section 4). The role of IAA in plant-bacteria interactions was also discussed in the study [10] and another review [11].

The above-mentioned review of natural, mainly plant oximes focused on the structures, distribution, biosynthesis, and biological activities of these compounds [1].

However, a review focusing on the role of Oxds and nitrile-converting enzymes in plant-bacteria interactions is lacking. The metabolism of oximes and nitriles is evidently important for plant-bacterial cross-talk, resulting in metabolites found in both microbes and plants. Therefore, in this survey, we will summarize what is known about the activities of bacterial Oxds, NLases, and NHases toward plant compounds.

We will also analyze the taxonomic and ecological distribution of these enzymes. In addition, we will discuss their role in some plant-growth-promoting bacteria and phytopathogens. Finally, we propose possible topics for future studies in this field.

2. Substrate Specificity

The transformation of the aldoxime IAOx into the corresponding nitrile in microbes (fungi) was noticed in the 1960s [12]. However, the discovery of the first Oxds was reported only about two decades ago. These were Oxds from Rhodococcus sp. YH3-3 [13], Bacillus sp. OxB-1 [14], and Pseudomonas chlororaphis B23 [15]. NLases have been known since the 1960s and their spectrum has been expanded since then [6,16]. The first report on NHase appeared in 1980 [17]. Previous reviews largely focused on the use of the enzymes for industrially important reactions [5,7,9]. In the following, we analyze the data on the substrate specificity of these enzymes for plant oximes and nitriles.

2.1. Aldoxime Dehydratases

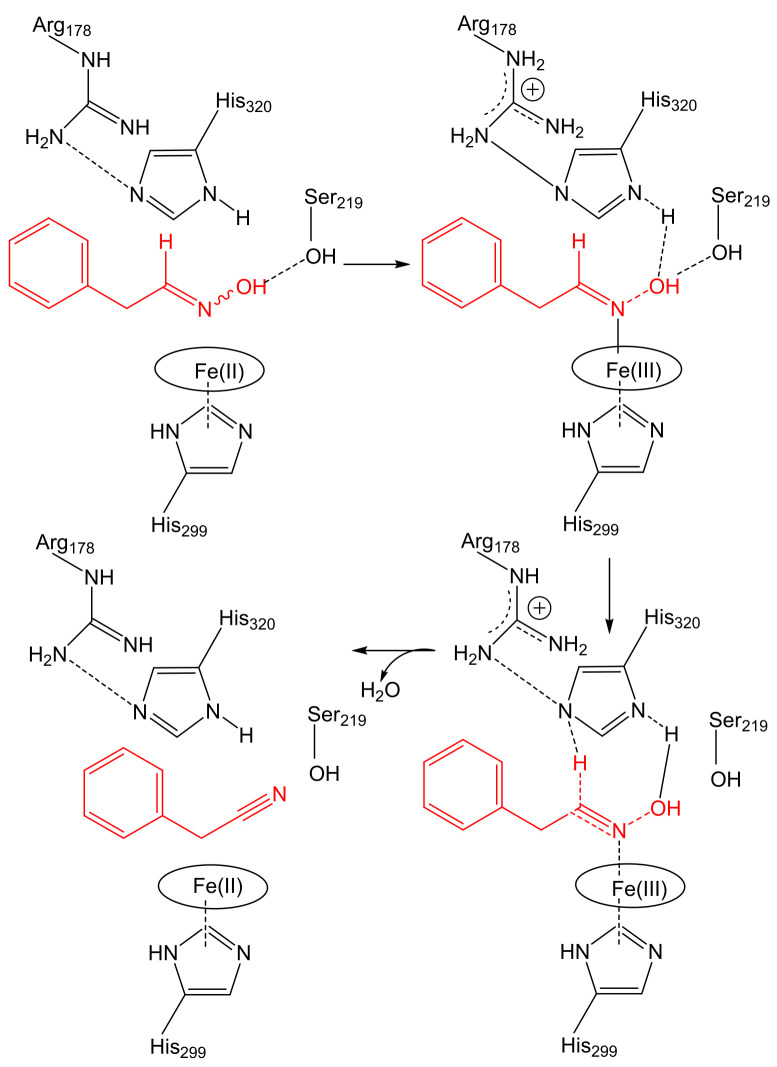

Oxds are unique heme enzymes that catalyze the dehydration of aldoximes in an aqueous environment. The catalytic Fe(II) atom is essential for the correct binding of the oxime via the N-atom of the oxime (Figure 2); Fe(III) is inactive.

Figure 2.

The binding of the substrate, phenylacetaldoxime, in the catalytic center of aldoxime dehydratase and release of the product, phenylacetonitrile; according to [18], modified. Amino acid numbering as in OxdA from Pseudomonas chlororaphis B23. Substrate and product in red.

Currently, there are about six characterized Oxds in bacteria (Table 1), and two in fungi [19,20]. The two Oxds in Pseudomonas are ≈90% identical [15,21]. Another pair of very similar Oxds (≈96% identity) is from Rhododoccus [22,23]. The Oxds of Rhodococcus are ≈76% identical to those of Pseudomonas, but those of Bradyrhizobium sp. [24] and Bacillus sp. [25] are more distant with ≈47% and ≈32% identity, respectively.

Table 1.

Identities (approximated) between amino acid sequences of bacterial aldoxime dehydratases (according to [26]). Coverage % in brackets.

| OxdB (BAA90461.1) | OxdRG (BAC99076.1) 1 |

OxdK (BAD98528.1) 2 | OxdBr1 (WP_044589203) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bacillus sp. OxB-1) [25] | (Rhododoccus globerulus A-4 [22] | (Pseudomonas sp. K-9) [21] | (Bradyrhizobium sp. LTSPM299) [24] | |

| OxdB | − | 32 (92) | 32 (93) | 32 (93) |

| OxdRG | − | − | 76 (99) | 47 (98) |

| OxdK | − | − | − | 47 (99) |

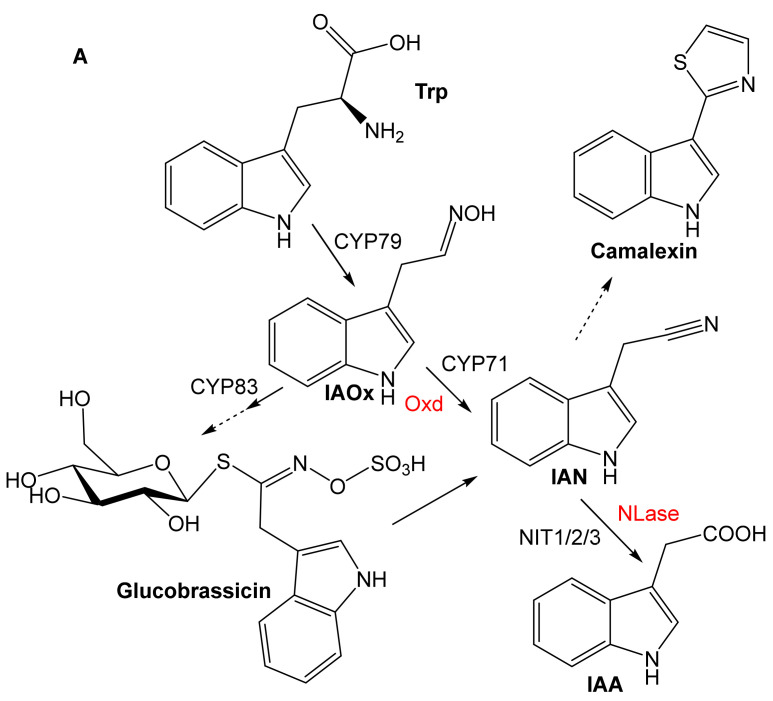

The characterized Oxds transform several plant aldoximes in addition to other (non-natural) aldoximes. The plant oximes were identified based on the above-mentioned review [1]. They are IAOx, phenylacetaldoxime (PAOx), 3-phenylpropionaldoxime (PPOx), isobutyraldoxime (iBuOx), and isovaleraldoxime (iVaOx). IAOx is formed from l-Trp and is a precursor of glucobrassicin and camalexin that is formed via IAN (Figure 3A). However, its role as a precursor of IAA is not entirely clear (Section 4). PAOx is formed from l-Phe, and its dehydration yields phenylacetonitrile (PAN). It is also a precursor of amygdalin or prunasin (CGs) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Plant and bacterial metabolism of (A) indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx), (B) phenylacetaldoxime (PAOx), 3-phenylpropionaldoxime (PPOx), (C) isobutyraldoxime (iBuOx), 2-methylbutyraldoxime (MeBuOx), isovaleraldoxime (3-methylbutyraldoxime; iVaOx), and methionine analogs (according to [1,3,27], modified). Plant and bacterial enzymes are shown in black and red, respectively. The hydroxy derivatives of iVaN are transformed to various glucosides (not shown). AFE, aldoxime-forming enzymes; APBA, 2-amino-4-phenylbutyric acid; CYP, cytochrome P450 (CYP71, CYP79, and CYP83 family); IAN, indole-3-acetonitrile; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; iBuN, isobutyronitrile; iVaN, isovaleronitrile; MeBuN, 2-methylbutyronitrile; NIT1/2/3, plant nitrilases of NIT1, NIT2, and NIT3 type; NLase, nitrilase; PAA, phenylacetic acid; PAN, phenylacetonitrile; PPA, 3-phenylpropionic acid; PPN, 3-phenylpropionitrile; UGT, UDP-glucosyl transferase.

PPOx is formed from l-Phe via 2-amino-4-phenylbutyric acid (APBA) and is a precursor of gluconasturtiin (Figure 3B). The aliphatic oximes isobutyraldoxime (iBuOx) and isovaleraldoxime (iVaOx) are synthesized from l-Val and l-Leu, respectively (Figure 3C). They are widespread anti-herbivore compounds and floral scents. In addition, iBuOx is a precursor of linamarin [1], whereas the transformation of iVaOx leads to α-, β-, and γ-hydroxynitriles—precursors of the glucosides epidermin, epiheterodendrin, (dihydro)osmaronin, and sutherlandin [27]. Met analogs are transformed to thioaldoximes, which are precursors of aliphatic glucosinolates in Brassicales (Arabidopsis) [1]. Bacterial enzymes that may transform the plant compounds are also shown in Figure 3.

OxdB of Bacillus sp. OxB-1 [14], OxdK of Pseudomonas sp. K-9 [21], and OxdRG of Rhodococcus globerulus A-4 [22] transformed IAOx, PAOx, PPOx, and at least one aliphatic oxime (Table 2). However, their preferred substrates are different: arylaliphatic aldoximes (PPOx, PAOx) in OxdB and OxdRG and the aliphatic compound iVaOx in OxdK. IAOx is an acceptable substrate for OxdB and OxdRG, but OxdK has a very low activity for it. The KM values are relatively high (≈0.5−5.5 mM) in all cases.

Table 2.

Substrate specificities of selected bacterial aldoxime dehydratases toward plant oximes.

| Enzyme 1 | Substrate 2 | Relative Activity (%) | Vmax [U/mg] | KM [mM] | Vmax/KM [U/mg/mM] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OxdB [14] |

IAOx | 18 | 5.42 | 2.40 | 2.26 |

| iVaOx | 20 | 7.72 | 3.58 | 2.16 | |

| Z-PAOx | 100 | 19.5 | 0.872 | 22.4 | |

| Z-PPOx | 63 | 14.3 | 1.36 | 10.5 | |

| OxdK [21] |

IAOx | 1 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| iBuOx | 14 | 5.87 | 0.538 | 10.9 | |

| iVaOx | 100 | 35.1 | 1.33 | 26.4 | |

| Z-PAOx | 7 | 2.61 | 0.991 | 2.63 | |

| Z-PPOx | 31 | 12.1 | 0.975 | 12.4 | |

| OxdRG [22] |

IAOx | 11 | 0.281 | 3.91 | 0.072 |

| iBuOx | 39 | 0.041 | 5.54 | 0.007 | |

| iVaOx | 87 | 0.239 | 3.97 | 0.060 | |

| Z-PAOx | 40 | 0.140 | 1.40 | 0.100 | |

| Z-PPOx | 100 | 0.392 | 2.31 | 0.170 |

1 See Table 1. 2 IAOx, indole-3-acetaldoxime; iBuOx, isobutyraldoxime; iVaOx, isovaleraldoxime (3-methylbutyraldoxime); PAOx, phenylacetaldoxime; PPOx, 3-phenylpropionaldoxime. The substrates are of E/Z-configuration unless noted otherwise. Substrates with the highest relative activity and Vmax/KM are in bold.

OxdRG showed lower Vmax values [22] than the other Oxds. However, the activity increased under altered conditions [21]. In particular, anaerobic conditions were important to prevent the oxidation of the Fe(II) cofactor. Thus, the specific activity increased from less than 0.1 U/mg to 633 U/mg for Z-PAOx [21]. However, kinetic data were not reported for these conditions.

OxdBr1 of Bradyrhizobium sp. LTSPM299 was found to be similar to OxdB and OxdRG in terms of substrate specificity [24]. The Oxd of Rhododoccus sp. YH3-3 was tested with whole cells. iBuOx was dehydrated, but not IAOx, PAOx, or PPOx [28]. Kinetic data were not determined for these enzymes.

2.2. Nitrile-Converting Enzymes

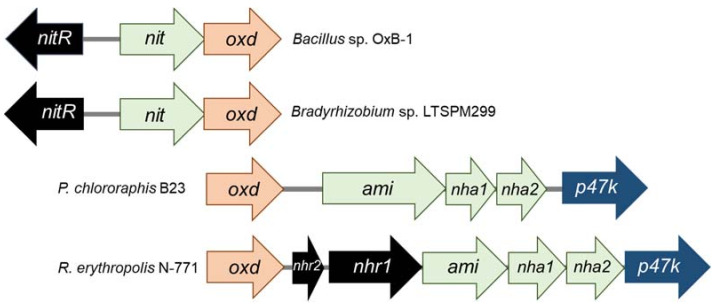

The above Oxd-producing bacteria also harbor genes for nitrile-converting enzymes—NLases in Bacillus sp. and Bradyrhizobium sp. and NHases in P. chlororaphis and Rhodococcus erythropolis. The genes for Oxd and NLase or NHase/Ami form clusters that are species- and strain-specific (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Genes encoding enzymes of the aldoxime-nitrile pathway form clusters (according to [15,21,23,24], modified). Examples: Bacillus sp. OxB-1, Bradyrhizobium sp. LTSPM299, Pseudomonas chlororaphis B23, and Rhodococcus erythropolis N-771. Encoded enzymes: nit, NLase; nha1, NHase α-subunit; nha2, NHase β-subunit. Blue arrows indicate genes coding for the putative NHase activator P47K. Black arrows indicate genes coding for putative transcriptional regulators (type specified). The flanking regions in P. chlororaphis and R. erythropolis contain some unidentified genes (not shown).

Two hypothetical genes were found upstream of the oxd gene in Bacillus and Brady-rhizobium [23,24]. They probably encode an NLase and a transcriptional regulator NitR, which belongs to the AraC family. The clusters in Rhodococcus and Pseudomonas are more complex. Both encode two NHase subunits, an amidase, and the NHase activator P47K [14,15]. The NHases in P. chlororaphis B23 and R. erythropolis N-771 are of Fe-type (with an Fe(III) cofactor) [29,30]. The NHase activator likely incorporates Fe into the active site [31]. However, its homolog in Pseudomonas sp. was found to be not necessary for NHase activity [32].

The substrate specificities of the NHases linked to Oxds are partially known. The NHase of P. chlororaphis transforms n-alkyl nitriles but not iVaN or PAN [29]. In contrast, the NHase from R. erythropolis N-771 was found to have a good activity for iBuN [30]. The NHase in Rhododoccus sp. YH3-3 was also characterized [28]. It belongs to the Co-type (with a Co(III) cofactor). It showed high activity for PAN, but lower activities for iBuN, IAN, and 3-phenylpropionitrile (PPN). Thus, some of the nitriles produced by the Oxds are substrates of NHases.

In contrast, less is known about the substrate specificity of the above NLases. The NLase of Bacillus sp. hydrolyzed PAN [14]. The NLase of Bradyrhizobium sp. LTSPM299 was not studied but it has a close homolog with activity for mandelonitrile [24]. This homolog was expressed from metagenomic DNA [33]. In addition, another homolog was characterized in Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 [34], which was reclassified as Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens [26]. The best substrates of this homolog were found to be mandelonitrile and PAN [34].

3. Taxonomic and Ecological Distribution

The distribution of Oxds in bacteria was assessed based on activity and gene screening [35,36] and on data from the GenBank database [26] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of aldoxime dehydratases, nitrilases, and nitrile hydratases in bacteria.

| Phylum | Genus | Number of Sequences 1 | Number of Active Strains 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxd | NLase | NHase | |||

| Actinobacteria | Arthrobacter | 5 | 16 | 5 | n.d. |

| Cellulomonas | - | 10 | - | n.d. | |

| Corynebacterium | 3 | 3 | - | 2 | |

| Brevibacterium | 1 | 41 | 1 | n.d. | |

| Gordonia | 4 | 6 | 13 | n.d. | |

| Microbacterium | 5 | 27 | 9 | 1 | |

| Nitriliruptor | 2 | 3 | 1 | n.a. | |

| Micrococcus | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Nocardia | 1 | 36 | 7 | 2 | |

| Rhodococcus | 142 | 190 | 107 | 14 | |

| Streptomyces | 8 | 157 | 252 | n.d. | |

| Firmicutes | Bacillus | 2 | 15 | 2 | 2 |

| Brevibacillus | 2 | 66 | - | n.a. | |

| Cytobacillus | 1 | 1 | - | n.a. | |

| Geomicrobium | 1 | 1 | - | n.a. | |

| Paenibacillus | 1 | 99 | 13 | n.a. | |

| Siminovitchia | 3 | 14 | - | n.a. | |

| Proteobacteria | Afipia | 2 | - | 14 | n.a. |

| Agrobacterium | 9 | 99 | 43 | n.d. | |

| Bradyrhizobium | 248 | 101 | 298 | n.a. | |

| Erwinia | 1 | 19 | 5 | n.d. | |

| Gibbsiella | 1 | 10 | 2 | n.a. | |

| Herbaspirillum | 1 | 45 | 9 | n.a. | |

| Klebsiella | - | 17 | 66 | n.d. | |

| Novosphingobium | 1 | 68 | 1 | n.a. | |

| Paraburkholderia | 1 | 336 | 139 | n.a. | |

| Proteus | - | 1 | 2 | n.d. | |

| Pseudomonas | 48 | 261 | 50 | 2 | |

| Pseudomaricurvus | 1 | - | - | n.a. | |

| Rhizobium | 7 | 270 | 600 | n.a. | |

| Serratia | - | 4 | 11 | n.d. | |

| Variovorax | 73 | 156 | 92 | n.d. | |

| Xanthomonas | 2 | 1 | 2 | n.d. | |

| Bacteroidetes 3 | Flavobacterium | - | 172 | 4 | n.d. |

| Maribacter | 1 | 58 | - | n.a. | |

1 Retrieved from [26]. Searches for hypothetical Oxds were performed using OxdBr1 (WP_044589203 [24]) as a template. Searches for hypothetical NLases and NHases were performed using the NLase from Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (NP_770037 [34]) and the α-subunit of the NHase from Rhododoccus erythropolis N-771 (2AHJ_A [42]) as templates, respectively. 2 According to [35]. The active strains exhibited both aldoxime dehydratase and nitrile-hydrolyzing activity for phenylacetaldoxime and phenylacetonitrile, respectively; n.a., not assayed; n.d., not detected. 3 Other four Oxds were identified in a bacterium of the Chitinophagaceae family in Bacteroidetes.

The screening of Oxd activities included 540 bacterial strains and 435 fungal strains including yeasts [35]. The substrates tested were PAOx and pyridine-3-aldoxime. The latter was not one of the plant oximes [1]. Therefore, we focus on the activity for PAOx. This was present at significant levels in over twenty bacteria and over thirty fungi including two yeasts. The study also examined the hydrolysis of the corresponding nitriles. These activities were generally present in the strains with Oxd activities. The Oxd activities were most abundant in rhodococci.

In addition, the distribution of Oxds in some bacteria selected by the above screening was investigated by Southern hybridization and PCR amplification [36]. The hybridization procedure used probes based on oxd genes from R. erythropolis N-771. This allowed for the identification of oxd genes in Rhodococcus sp. NCIBM 11215 and NCIBM 11216, R. erythropolis strains JCM 3201, BG13, and B16, Brevibacterium butanicum ATCC 21196, and Pseudomonas sp. K-9. These strains and Bacillus sp. OxB-1 also gave positive results in PCR amplification with primers based on conserved oxd regions. PCR was also performed with primers for Fe-type and Co-type NHases. The nha1 genes (Figure 4) were found in almost all strains of rhodococci shown to have oxd genes, in Pseudomonas sp. K-9, and in B. butanicum ATCC 21196. All of these NHases were identified as Fe-type.

According to GenBank searches, Oxds are most abundant in the phyla Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. The phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes contain few Oxds.

Among the Actinobacteria, the greatest number of putative Oxds was found in Rhodococcus, in accordance with the above-mentioned activity screening. A few were also found in Arthrobacter, Corynebacterium, Microbacterium, or Streptomyces. These bacteria are widely distributed in water and soils, typically in the rhizosphere [37,38,39]. They also include endophytic bacteria belonging to Rhododoccus [40] or Streptomyces [41].

Among the Proteobacteria, Oxds are most abundant in the Bradyrhizobium, Variovorax, and Pseudomonas genera. The habitat of Bradyrhizobium is typically the rhizosphere but also forest soils [43,44]. Members of the genus Pseudomonas occur, e.g., in soils and the rhizosphere [39,45] or as endophytes [45]. Variovorax is common in the rhizosphere among several other environments [46]. Several Oxds also occur in each of the genera Rhizobium (rhizobacteria [47]) and Agrobacterium (endophytes, rhizobacteria; [37,48,49]).

In the Firmicutes, most of the Oxds were found in Bacillus, Brevibacillus and the related genus Siminovitchia, while some other genera contain a single Oxd. Bacilli have a number of different habitats including the rhizosphere and also include endophytic bacteria [45].

In general, the genera with oxd genes also contain nitrilase (nit) genes. NLases are much more diverse than Oxds in terms of substrate specificity. There are several types of NLases: aromatic NLases, arylacetoNLases, plant NLase homologs, thermostable NLase, etc. [2,50]. In addition, some putative NLases differ significantly in sequence from characterized NLases, and thus may have other substrate specificities. NLases are distributed throughout bacterial phyla. The highest number of NLase sequences was found in Rhododoccus, Streptomyces, Paraburkholderia, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Variovorax, and Flavobacterium. The typical habitats of these bacteria are soils.

NHases are more conserved; Fe-type and Co-type NHases are about 50% identical. They are less widely distributed than NLases, as only a few were found in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. In Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, their distribution is similar to that of NLases, with a few exceptions.

4. Potentiality of the Aldoxime-Nitrile Pathway in Plant-Associated Bacteria

The bacterial ability to detoxify oximes and nitriles appears to be advantageous in both mutualistic and parasitic lifestyles. Bacterial symbionts may also benefit from this ability in different ways, such as modulating plant growth through interactions with plant hormone synthesis.

The interaction of plant-growth-promoting bacteria with the host plant is complex. The beneficial effects are associated with the bacterial ability to produce IAA, nutrients (ammonia, phosphate), surfactants, siderophores, or enzymes that attack the cell wall polysaccharides in fungal pathogens [51]. Other mechanisms strengthen the plant cell wall, prevent an excessive production of the plant hormone ethylene [51], or change the distribution of the plant hormone abscisic acid [52].

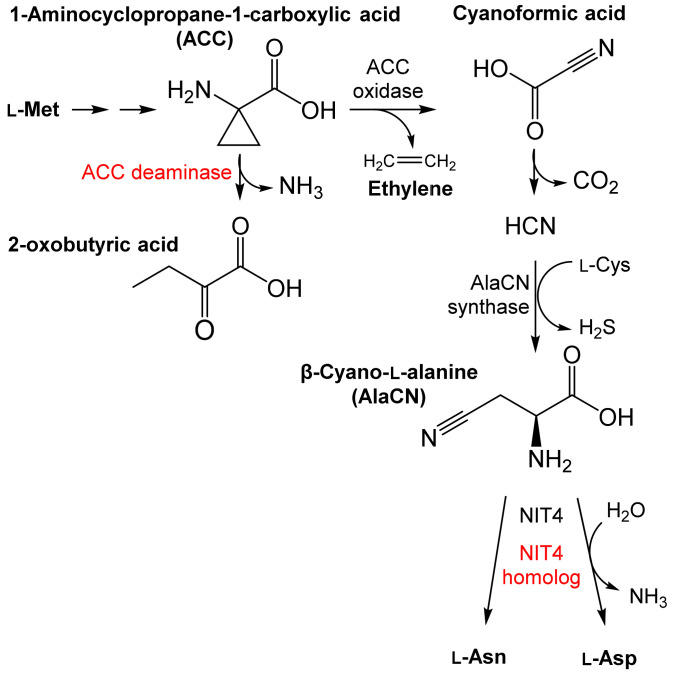

In the pathway to ethylene (Figure 5), the intermediate 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) can be degraded by the bacterial ACC deaminase [52] (EC 3.5.99.7). If not degraded, ACC is transformed to ethylene and cyanoformic acid by the plant ACC oxidase (EC 1.14.17.4); cyanoformic acid decomposes to CO2 and HCN. The latter is eliminated in the plant by reaction with L-Cys to form β-cyano-L-alanine (AlaCN). The enzyme that catalyzes this reaction (AlaCN synthase, EC 4.4.1.9) is widespread in plants but has been found in few bacteria [53]. The next step is the hydrolysis of AlaCN [2]. Plant NLases of the NIT4 type are highly specific for AlaCN [2,3]. The presence of similar NLases in bacteria such as Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 [2,54] and fungi [55] suggests the possibility of horizontal gene transfer (HGT). HGT from bacteria to fungi was already demonstrated for ACC deaminase (acdS) genes [56]. The substrate specificity distinguishes NIT4 from NLases typical of the aldoxime–nitrile pathway.

Figure 5.

Biosynthesis of phytohormone ethylene in plants and detoxification of the byproduct HCN via β-cyano-l-alanine (AlaCN) (according to [2,52], modified). The synthesis of AlaCN proceeds in plants and, rarely, in bacteria. The hydrolysis of AlaCN proceeds in plants but also in some bacteria and fungi. NIT4, nitrilase specific for AlaCN (plant enzymes in black, bacterial enzymes in red).

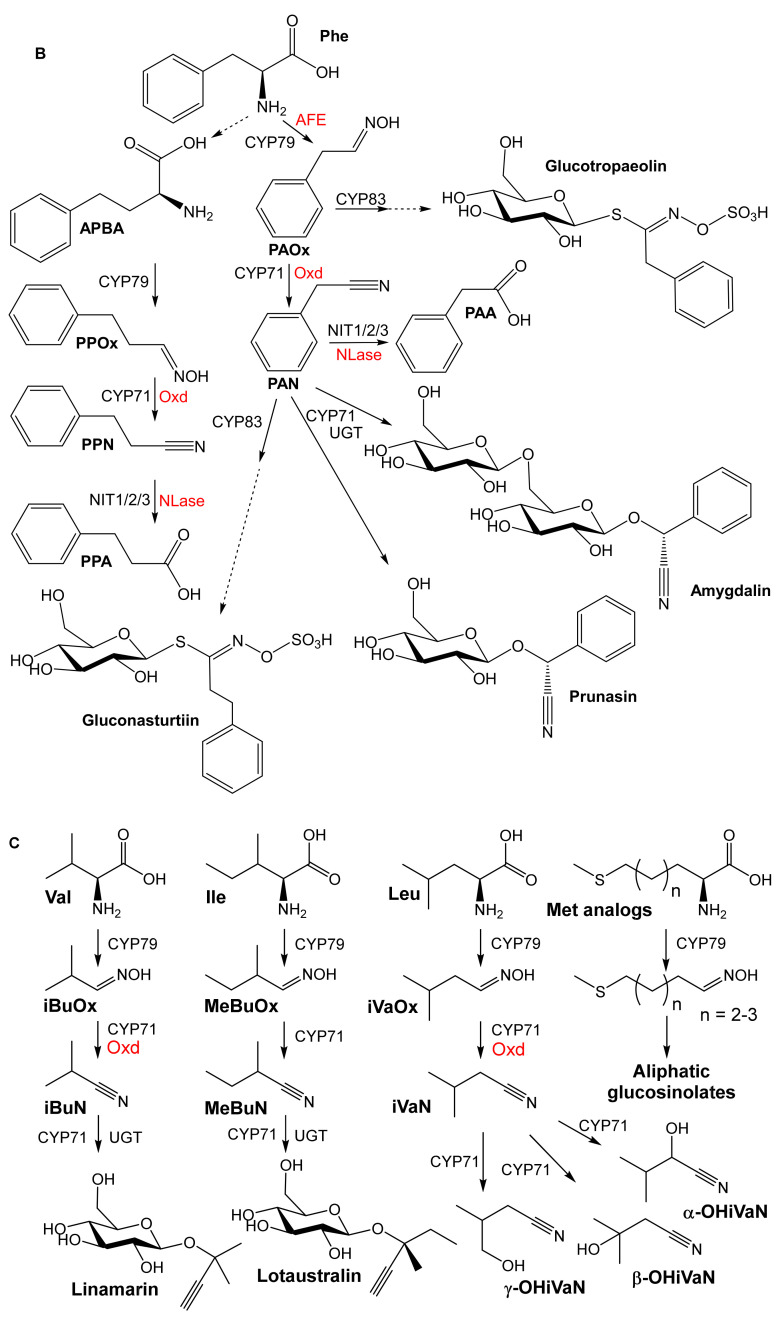

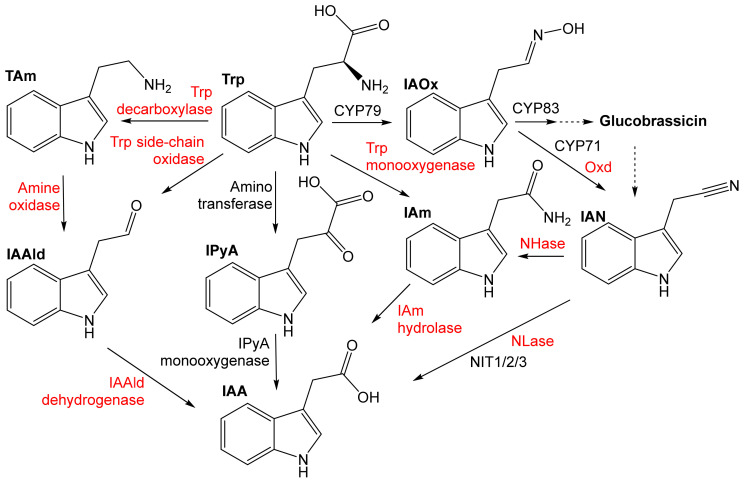

The Trp-dependent pathways to the phytohormone IAA involve the indole-3-acetamide (IAm), indole-3-pyruvate (IPyA), tryptamine (TAm), Trp side-chain oxidase (TSO), and IAN pathway (Figure 6). The preferential pathways in plants and microbes are different. Plants have been assumed to mainly synthesize IAA via IPyA, tryptamine, and probably also IAM and IAN. Currently, the most studied metabolic pathway is the Trp–IPyA–IAA pathway catalyzed by an amino transferase and a monooxygenase of the YUCCA family [57,58]. IAAld has been found not to be an intermediate of the IPyA pathway, as previously thought [59]. Bacteria have been assumed to largely produce IAA via the IAM and IPyA pathway, with some rare examples of the IAN, TAM, and TSO pathway [10]. It is still largely unclear to what extent IAA is formed in bacteria or plants from IAOx or IAN. Plants probably hydrolyze IAN to IAA under certain conditions (lack of sulfur, infection) [3]. Both bacteria and plants may also synthesize IAA by the Trp-independent pathways from indole or indole-3-glycerolphosphate [10].

Figure 6.

Trp-dependent biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in bacteria and plants (according to [1,3,10,57,58,59], modified). Enzymes typical of plants and bacteria are shown in black and red, respectively. IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; IAAld, indole-3-acetaldehyde; IAOx, indole-3-acetaldoxime; IAm, indole-3-acetamide; IAN, indole-3-acetonitrile; CYP, cytochrome P450 (CYP71, CYP79, and CYP83 family); IPyA, indole-3-pyruvate; NIT1/2/3, plant nitrilases of NIT1, NIT2, and NIT3 type; NLase, nitrilase.

IAA has versatile biological activities. It supports germination and growth, triggers plant resistance mechanisms, and also has nematocidal activity [60]. However, IAA only has plant-promoting effects within a restricted range of concentrations [51]. The regulation of IAA production in bacteria is also sensitive to environmental factors [10]. The production of IAA by microbes can interfere with plant defense and physiology in many ways.

The endophyte P. fluorescens BRZ63 showed biocontrol activity against some fungal pathogens (Rhizoctonia, Sclerotinia, Colletotrichum, and Fusarium) in Brassica napus (oilseed rape). The bacterium improved plant fitness by a complex mechanism that also included the production of significant concentrations of IAA (0.06 mg/mL) [51]. Another strain of P. fluorescens protected the host plant (Medicago trunculata, a legume) against the fungus Botrytis cinerea at lower IAA concentrations (0.022 mg/mL). The strains with lower IAA production (<0.001 to ≈0.01 mg) did not promote shoot growth, notwithstanding the fungal infection [61].

Production of IAA from IAN or IAOx in P. fluorescens is possible, as the corresponding genes are present. In addition, IAN can be produced from glucobrassisin in Brassicaceae [3]. On the other hand, P. fluorescens may also transform Trp to IAA via IAAld produced by direct oxidation of Trp under specific conditions (stationary phase) [10].

P. fluorescens has several tens of putative Oxds. Some of them are most similar to OxdK from Pseudomonas sp. K-9 (up to 97% identity) and some to OxdRG from R. globerulus A-4 (up to 78% identity). OxdK has a non-zero activity for IAOx, and OxdRG has a good activity for this substrate (Section 2). P. fluorescens also has dozens of NLases. One of them (AAW79573) is an arylacetoNLase with significant activities for PAN, IAN, or PPN, and also for mandelonitrile. In this strain, P. fluorescens EBC191, genes corresponding to the mandelate pathway were found in the proximity of the nit gene but no oxd gene was found [62]. Thus, it is an example of an NLase that is not part of the ANP. However, a putative indole-3-acetamide (IAm) hydrolase gene was present upstream of the nit gene. IAm hydrolase is an enzyme of the IAm pathway [10] (Figure 6). Functional expression of the genes for the mandelate pathway was confirmed by demonstrating the growth of the strain on mandelate as the sole source of N; this pathway, together with nitrilase, is thought to allow for bacterial utilization of mandelonitrile released from plants [62].

The rhizobacterium Variovorax paradoxus 5C-2 supports plant growth in a variety of ways, including ACC deamination (Figure 5) and abscisic acid distribution between plant tissues in Pisum sativum [52]. It also produces IAA (e.g., 0.075 mg/L [52]) in media containing Trp [52,63]. However, Trp concentrations in plant exudates (the Trp source for rhizobacteria) may not be sufficient [64]. This allows us to consider alternative pathways of IAA synthesis such as the aforementioned Trp-independent pathway [10]. However, we also cannot exclude the synthesis of IAA from the plant-produced IAOx or IAN. V. paradoxus has 12 putative Oxds, all of which are relatively similar (≈50% identical) to the Oxds active for IAOx (OxdBr1, OxdRG). The species V. paradoxus also contains over 40 NLases. Most of them are closely related to the NLase Nit6803 from Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 [65], whose homologs are collectively referred to as the Nit6803 NLase family. The best substrate of this NLase is fumaronitrile, but a variety of structurally diverse substrates including IAN are also accepted [66].

Fungi are also able to transform oximes to carboxylic acids, which may add complexity to plant-microbial interactions. One of the oilseed rape (Brassica napus) pathogens, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum clone #33 [51], has an Oxd with a narrow specificity for a few aldoximes, while IAOx is its best substrate. However, the activity of the purified enzyme is low (0.014 U/mg protein) [19]. Another Oxd was characterized in Fusarium graminearum MAFF305135, which causes head blight in some crops. This enzyme showed high activity for IAOx (Vmax of 19.3 U/mg protein), but also for PAOx, PPOx, and aliphatic nitriles [20]. These are the only two fungal Oxds that have been characterized, but Ascomycota contain many more Oxds. Hundreds of fungal Oxd sequences have been deposited in GenBank, while less than ten were found in Basidiomycota. Ascomycota are also remarkably rich in NLases with several thousands of sequences, while approximately two hundred NLases were found in Basidiomycota [55,67]. Fusarium and its teleomorph Gibberella have dozens of NLases, some of which were characterized. They include several substrate-specificity types [6]. They are generally active towards PAN, whereas their specificity for other natural nitriles is still largely unclear.

The transformation of mutualistic bacteria to pathogens is relatively simple. For example, the pathogenicity of Rhodococcus fascians D188 depends on the production of cytokinins. This was enabled in the strains that had acquired the virulent plasmid [68,69]. R. fascians increases the IAA concentration in the plant by about tenfold, but the role of this effect in pathogenesis is largely unclear. No intermediates corresponding to the IAN, IAM, or TAm pathways were found at significant levels. The study suggested that the indole-3-pyruvate pathway (Figure 6) is the main route to IAA in this organism [70]. Thus, the role of the approximately ten oxd genes found in this taxon is still poorly understood.

5. Conclusions

The long coexistence of plants and microbes has led to a variety of close relationships (symbiosis). The bacterial symbionts must have pathways that detoxify plant defenses. One of these pathways is ANP, which likely confers detoxification and assimilation capabilities to the bacteria. It may also have a signaling function. Here, we summarized the data that shed light on the role of this pathway in plant-associated bacteria and the interaction with their host plants. Moreover, NLases are much more diverse than Oxds in terms of sequence and substrate specificity. They can also act outside the ANP, e.g., in the degradation of the toxic plant metabolites AlaCN and mandelonitrile.

First, we analyzed data on the substrate specificity of the characterized bacterial Oxds. It has been shown that some plant oximes are Oxd substrates in vitro. We have also investigated whether the nitrile-converting enzymes in the same organisms are capable of converting the Oxd products—nitriles. This is likely for most nitriles, as indicated by the data on these enzymes or their homologs.

We then examined the distribution of Oxds using data from activity screening and database mining. It became clear that there are hundreds of oxd genes in bacteria, but they are unevenly distributed. Oxds are only abundant in four genera—Bradyrhizobium, Rhodoccus, Pseudomonas, and Variovorax—along with NLases or NHases. NLases are the most abundant. Oxds and nitrile-converting enzymes are common in both plant-growth-promoting bacteria and plant pathogens, and can alter plant growth or defense via, e.g., IAA production. However, studies that could explain the mechanisms of this plant-bacterial cross-talk are largely lacking.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the administrative and technical support by Petr Novotný (Institute of Microbiology of the Czech Academy of Sciences).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R., M.P. and L.M.; formal analysis, L.M.; data curation, B.K. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, M.P., V.K. and M.W.; supervision, M.P. and L.M.; project administration M.W., M.P. and L.M.; funding acquisition, M.W., M.P. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Czech Science Foundation, grant number GF20-23532L, the Charles University Grant Agency, grant number 452120, and by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, grant number I 4607.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sørensen M., Neilson E.H.J., Møller B.L. Oximes: Unrecognized chameleons in general and specialized plant metabolism. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:95–117. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howden A.J., Preston G.M. Nitrilase enzymes and their role in plant-microbe interactions. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009;2:441–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piotrowski M. Primary or secondary? Versatile nitrilases in plant metabolism. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:2655–2667. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato Y., Tsuda T., Asano Y. Purification and partial characterization of N-hydroxy-l-phenylalanine decarboxylase/oxidase from Bacillus sp. strain OxB-1, an enzyme involved in aldoxime biosynthesis in the “aldoxime-nitrile pathway”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1774:856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betke T., Higuchi J., Rommelmann P., Oike K., Nomura T., Kato Y., Asano Y., Gröger H. Biocatalytic synthesis of nitriles through dehydration of aldoximes: The substrate scope of aldoxime dehydratases. ChemBioChem. 2018;19:768–779. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201700571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínková L. Nitrile metabolism in fungi: A review of its key enzymes nitrilases with focus on their biotechnological impact. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2019;33:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2018.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen J.-D., Cai X., Liu Z.-Q., Zheng Y.-G. Nitrilase: A promising biocatalyst in industrial applications for green chemistry. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020;41:72–93. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2020.1827367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolz A., Eppinger E., Sosedov O., Kiziak C. Comparative analysis of the conversion of mandelonitrile and 2-phenylpropionitrile by a large set of variants generated from a nitrilase originating from Pseudomonas fluorescens EBC191. Molecules. 2019;24:4232. doi: 10.3390/molecules24234232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhalla T.C., Kumar V., Kumar V. Enzymes of aldoxime-nitrile pathway for organic synthesis. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio-Technol. 2018;17:229–239. doi: 10.1007/s11157-018-9467-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spaepen S., Vanderleyden J., Remans R. Indole-3-acetic acid in microbial and microorganism-plant signaling. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007;31:425–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santoyo G., Moreno-Hagelsieb G., Orozco-Mosqueda Mdel C., Glick B.R. Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes. Microbiol. Res. 2016;183:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahadevan S. Conversion of 3-indolacetaldoxime to 3-indoleacetonitrile by plants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1963;100:557–558. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(63)90127-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato Y., Ooi R., Asano Y. Isolation and characterization of a bacterium possessing a novel aldoxime-dehydration activity and nitrile-degrading enzymes. Arch. Microbiol. 1998;170:85–90. doi: 10.1007/s002030050618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato Y., Nakamura K., Sakiyama H., Mayhew S.G., Asano Y. Novel heme-containing lyase, phenylacetaldoxime dehydratase from Bacillus sp. strain OxB-1: Purification, characterization, and molecular cloning of the gene. Biochemistry. 2000;39:800–809. doi: 10.1021/bi991598u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oinuma K., Hashimoto Y., Konishi K., Goda M., Noguchi T., Higashibata H., Kobayashi M. Novel aldoxime dehydratase involved in carbon-nitrogen triple bond synthesis of Pseudomonas chlororaphis B23. Sequencing, gene expression, purification, and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:29600–29608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínková L., Rucká L., Nešvera J., Pátek M. Recent advances and challenges in the heterologous production of microbial nitrilases for biocatalytic applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;33:11. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asano Y., Tani Y., Yamada H. A new enzyme nitrile hydratase which degrades acetonitrile in combination with amidase. Agr. Biol. Chem. 1980;44:2251–2252. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1980.10864311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinzmann A., Betke T., Asano Y., Gröger H. Synthetic processes toward nitriles without the use of cyanide: A biocatalytic concept based on dehydration of aldoximes in water. Chem. Eur. J. 2021;27:5313–5321. doi: 10.1002/chem.202001647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedras M.S., Minic Z., Thongbam P.D., Bhaskar V., Montaut S. Indolyl-3-acetaldoxime dehydratase from the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Purification, characterization, and substrate specificity. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1952–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato Y., Asano Y. Purification and characterization of aldoxime dehydratase of the head blight fungus, Fusarium graminearum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005;69:2254–2257. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato Y., Asano Y. Molecular and enzymatic analysis of the “aldoxime-nitrile pathway” in the glutaronitrile degrader Pseudomonas sp. K-9. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;70:92–101. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie S.X., Kato Y., Komeda H., Yoshida S., Asano Y. A gene cluster responsible for alkylaldoxime metabolism coexisting with nitrile hydratase and amidase in Rhodococcus globerulus A-4. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12056–12066. doi: 10.1021/bi035092u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato Y., Yoshida S., Xie S.-X., Asano Y. Aldoxime dehydratase co-existing with nitrile hydratase and amidase in the iron-type nitrile hydratase-producer Rhodococcus sp. N-771. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2004;97:250–259. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(04)70200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rädisch R., Chmátal M., Rucká L., Novotný P., Petrásková L., Halada P., Kotík M., Pátek M., Martínková L. Overproduction and characterization of the first enzyme of a new aldoxime dehydratase family in Bradyrhizobium sp. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;115:746–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato Y., Asano Y. High-level expression of a novel FMN-dependent heme-containing lyase, phenylacetaldoxime dehydratase of Bacillus sp. strain OxB-1, in heterologous hosts. Protein Expres. Purif. 2003;28:131–139. doi: 10.1016/S1046-5928(02)00638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. [(accessed on 2 February 2022)]; Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- 27.Knoch E., Motawie M.S., Olsen C.E., Møller B.L., Lyngkjaer M.F. Biosynthesis of the leucine derived alpha-, beta- and gamma-hydroxynitrile glucosides in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Plant. J. 2016;88:247–256. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato Y., Tsuda T., Asano Y. Nitrile hydratase involved in aldoxime metabolism from Rhodococcus sp. strain YH3-3 purification and characterization. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;263:662–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagasawa T., Nanba H., Ryuno K., Takeuchi K., Yamada H. Nitrile hydratase of Pseudomonas chlororaphis B23. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;162:691–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagamune T., Kurata H., Hirata M., Honda J., Koike H., Ikeuchi M., Inoue Y., Hirata A., Endo I. Purification of inactivated photoresponsive nitrile hydratase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;168:437–442. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(90)92340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nojiri M., Nakayama H., Odaka M., Yohda M., Takio K., Endo I. Cobalt-substituted Fe-type nitrile hydratase of Rhodococcus sp. N-771. FEBS Lett. 2000;465:173–177. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01746-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duca D., Rose D.R., Glick B.R. Characterization of a nitrilase and a nitrile hydratase from Pseudomonas sp. strain UW4 that converts indole-3-acetonitrile to indole-3-acetic acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:4640–4649. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00649-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson D.E., Chaplin J.A., DeSantis G., Podar M., Madden M., Chi E., Richardson T., Milan A., Miller M., Weiner D.P., et al. Exploring nitrilase sequence space for enantioselective catalysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:2429–2436. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2429-2436.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu D., Mukherjee C., Yang Y., Rios B.E., Gallagher D.T., Smith N.N., Biehl E.R., Hua L. A new nitrilase from Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110. Gene cloning, biochemical characterization and substrate specificity. J. Biotechnol. 2008;133:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato Y., Ooi R., Asano Y. Distribution of aldoxime dehydratase in microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:2290–2296. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2290-2296.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato Y., Yoshida S., Asano Y. Polymerase chain reaction for identification of aldoxime dehydratase in aldoxime- or nitrile-degrading microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005;246:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma M., Mishra V., Rau N., Sharma R.S. Increased iron-stress resilience of maize through inoculation of siderophore-producing Arthrobacter globiformis from mine. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2016;56:719–735. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worsley S.F., Newitt J., Rassbach J., Batey S.F.D., Holmes N.A., Murrell J.C., Wilkinson B., Hutchings M.I. Streptomyces endophytes promote host health and enhance growth across plant species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;86:e01053-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01053-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vick S.H.W., Fabian B.K., Dawson C.J., Foster C., Asher A., Hassan K.A., Midgley D.J., Paulsen I.T., Tetu S.G. Delving into defence: Identifying the Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 gene suite involved in defence against secreted products of fungal, oomycete and bacterial rhizosphere competitors. Microb. Genom. 2021;7:671. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzalez-Benitez N., Martin-Rodriguez I., Cuesta I., Arrayas M., White J.F., Molina M.C. Endophytic microbes are tools to increase tolerance in Jasione plants against arsenic stress. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:664271. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.664271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yandigeri M.S., Meena K.K., Singh D., Malviya N., Singh D.P., Solanki M.K., Yadav A.K., Arora D.K. Drought-tolerant endophytic actinobacteria promote growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum) under water stress conditions. Plant Growth Regul. 2012;68:411–420. doi: 10.1007/s10725-012-9730-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song L., Wang M.Z., Shi J.J., Xue Z.Q., Wang M.X., Qian S.J. High resolution X-ray molecular structure of the nitrile hydratase from Rhodococcus erythropolis AJ270 reveals posttranslational oxidation of two cysteines into sulfinic acids and a novel biocatalytic nitrile hydration mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;362:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.VanInsberghe D., Maas K.R., Cardenas E., Strachan C.R., Hallam S.J., Mohn W.W. Non-symbiotic Bradyrhizobium ecotypes dominate North American forest soils. ISME J. 2015;9:2435–2441. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones F.P., Clark I.M., King R., Shaw L.J., Woodward M.J., Hirsch P.R. Novel European free-living, non-diazotrophic Bradyrhizobium isolates from contrasting soils that lack nodulation and nitrogen fixation genes—A genome comparison. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25858. doi: 10.1038/srep25858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adeleke B.S., Babalola O.O., Glick B.R. Plant growth-promoting root-colonizing bacterial endophytes. Rhizosphere. 2021;20:100433. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han J.I., Choi H.K., Lee S.W., Orwin P.M., Kim J., Laroe S.L., Kim T.G., O’Neil J., Leadbetter J.R., Lee S.Y., et al. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile plant growth-promoting endophyte Variovorax paradoxus S110. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:1183–1190. doi: 10.1128/JB.00925-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agrawal M., Archana G. Phenotypic display of plant growth-promoting traits in individual strains and multispecies consortia of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and rhizobia under salinity stress. Rhizosphere. 2021;20:443. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo H., Glaeser S.P., Alabid I., Imani J., Haghighi H., Kämpfer P., Kogel K.H. The abundance of endofungal bacterium Rhizobium radiobacter (syn. Agrobacterium tumefaciens) increases in its fungal host Piriformospora indica during the tripartite sebacinalean symbiosis with higher plants. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:629. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cavalcanti M.I.P., Nascimento R.d.C., Rodrigues D.R., Escobar I.E.C., Fraiz A.C.R., de Souza A.P., de Freitas A.D.S., Nóbrega R.S.A., Fernandes-Júnior P.I. Maize growth and yield promoting endophytes isolated into a legume root nodule by a cross-over approach. Rhizosphere. 2020;15:100211. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2020.100211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thuku R.N., Brady D., Benedik M.J., Sewell B.T. Microbial nitrilases: Versatile, spiral forming, industrial enzymes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009;106:703–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chlebek D., Pinski A., Żur J., Michalska J., Hupert-Kocurek K. Genome mining and evaluation of the biocontrol potential of Pseudomonas fluorescens BRZ63, a new endophyte of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) against fungal pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:8740. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang F., Chen L., Belimov A.A., Shaposhnikov A.I., Gong F., Meng X., Hartung W., Jeschke D.W., Davies W.J., Dodd I.C. Multiple impacts of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Variovorax paradoxus 5C-2 on nutrient and ABA relations of Pisum sativum. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:6421–6430. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Omura H., Kuroda M., Kobayashi M., Shimizu S., Yoshida T., Nagasawa T. Purification, characterization and gene cloning of thermostable O-acetyl-L-serine sulfhydrylase forming beta-cyano-L-alanine. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003;95:470–475. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(03)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Howden A.J.M., Jill Harrison C., Preston G.M. A conserved mechanism for nitrile metabolism in bacteria and plants. Plant J. 2009;57:243–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rucká L., Kulik N., Novotný P., Sedova A., Petrásková L., Příhodová R., Křístková B., Halada P., Pátek M., Martínková L. Plant nitrilase homologues in fungi: Phylogenetic and functional analysis with focus on nitrilases in Trametes versicolor and Agaricus bisporus. Molecules. 2020;25:3861. doi: 10.3390/molecules25173861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruto M., Prigent-Combaret C., Luis P., Moënne-Loccoz Y., Muller D. Frequent, independent transfers of a catabolic gene from bacteria to contrasted filamentous eukaryotes. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2014;281:20140848. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Casanova-Sáez R., Voß U. Auxin metabolism controls developmental decisions in land plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24:741–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Enders T.A., Strader L.C. Auxin activity: Past, present, and future. Am. J. Bot. 2015;102:180–196. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mashiguchi K., Tanaka K., Sakai T., Sugawara S., Kawaide H., Natsume M., Hanada A., Yaeno T., Shirasu K., Yao H., et al. The main auxin biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:18512–18517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108434108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bogner C.W., Kamdem R.S., Sichtermann G., Matthäus C., Holscher D., Popp J., Proksch P., Grundler F.M., Schouten A. Bioactive secondary metabolites with multiple activities from a fungal endophyte. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017;10:175–188. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hernández-León R., Rojas-Solís D., Contreras-Pérez M., Orozco-Mosqueda M.d.C., Macías-Rodríguez L.I., Reyes-de la Cruz H., Valencia-Cantero E., Santoyo G. Characterization of the antifungal and plant growth-promoting effects of diffusible and volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains. Biol. Control. 2015;81:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kiziak C., Conradt D., Stolz A., Mattes R., Klein J. Nitrilase from Pseudomonas fluorescens EBC191: Cloning and heterologous expression of the gene and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Microbiology. 2005;151:3639–3648. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abdellatif L., Ben-Mahmoud O.M., Yang C., Hanson K.G., Gan Y., Hamel C. The H2-oxidizing rhizobacteria associated with field-grown lentil promote the growth of lentil inoculated with hup+ Rhizobium through multiple modes of action. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2016;36:348–361. doi: 10.1007/s00344-016-9645-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao S., Zhou N., Zhao Z.Y., Zhang K., Wu G.H., Tian C.Y. Isolation of endophytic plant growth-promoting bacteria associated with the halophyte Salicornia europaea and evaluation of their promoting activity under salt stress. Curr. Microbiol. 2016;73:574–581. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang L.J., Yin B., Wang C., Jiang S.Q., Wang H.L., Yuan Y.A., Wei D.Z. Structural insights into enzymatic activity and substrate specificity determination by a single amino acid in nitrilase from Syechocystis sp. PCC6803. J. Struct. Biol. 2014;188:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heinemann U., Engels D., Bürger S., Kiziak C., Mattes R., Stolz A. Cloning of a nitrilase gene from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 and heterologous expression and characterization of the encoded protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:4359–4366. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4359-4366.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rucká L., Chmátal M., Kulik N., Petrásková L., Pelantová H., Novotný P., Příhodová R., Pátek M., Martínková L. Genetic and functional diversity of nitrilases in Agaricomycotina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5990. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Savory E.A., Fuller S.L., Weisberg A.J., Thomas W.J., Gordon M.I., Stevens D.M., Creason A.L., Belcher M.S., Serdani M., Wiseman M.S., et al. Evolutionary transitions between beneficial and phytopathogenic Rhodococcus challenge disease management. Elife. 2017;6:e30925. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Savory E.A., Weisberg A.J., Stevens D.M., Creason A.L., Fuller S.L., Pearce E.M., Chang J.H. Phytopathogenic Rhodococcus have diverse plasmids with few conserved virulence functions. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1022. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vandeputte O., Oden S., Mol A., Vereecke D., Goethals K., El Jaziri M., Prinsen E. Biosynthesis of auxin by the gram-positive phytopathogen Rhodococcus fascians is controlled by compounds specific to infected plant tissues. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:1169–1177. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1169-1177.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]