Abstract

Context:

Diagnosis of papillary lesions of the breast by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is problematic. For this reason, it is situated in the indeterminate zone in classification systems.

Aims:

To ascertain the accuracy of cytological diagnosis of papillary lesions in distinguishing papillary lesions from non-papillary lesions and to determine whether papillomas can be reliably distinguished from malignant papillary lesions by FNAC.

Material and Methods:

A total of 346 cases with the diagnoses of breast papillary lesions were selected among 5112 breast FNAC procedures performed in our center. One hundred and thirty-nine cases with excised lesions were included in this study, and their corresponding histology was reviewed.

Results:

Papillary lesion diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology in 103 (74.1%) of 139 patients. Cytology and histopathology results were not found to be compatible in 35 (25.2%) cases. The diagnostic accuracy of distinguishing papillary breast lesions as malignant or benign was assessed statistically. According to the cytology–histology comparison, one case was evaluated as false negative (FN) and twelve cases as false positive (FP). Overall accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of FNAC in distinguishing papillary lesions as benign or malignant were calculated as 87%, 97%, 83%, 72%, and 98%, respectively.

Conclusions:

The diagnostic accuracy of papillary breast lesions classified by FNAC might be improved by careful evaluation together with cytological, radiological, and clinical findings (triple test). Cell block may allow more accurate evaluation of the papillary lesion and can be applied to immunohistochemical examination. It may also facilitate the differentiation of benign/malignant papillary lesions.

Keywords: Breast, FNAC, papillary carcinoma, papillary lesion, papilloma

INTRODUCTION

Papillary lesions of the breast are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms, which account for less than 5% of benign breast neoplasms and 0.5–2% of all breast malignancies.[1] Papillary lesions are predominantly formed by papilla containing a fibrovascular core. Breast papillary lesions are distinguished as benign or malignant according to the structure of the papilla, the nature of epithelium lining the papilla, and the presence or absence of myoepithelial cells. Papillary lesions of the breast are histopathologically classified as intraductal papilloma (IP), papilloma with atypical ductal hyperplasia (AIP), papilloma with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS-P), encapsulated papillary carcinoma (EPC), solid papillary carcinoma (SPC), and invasive papillary carcinoma (IPC) according to World Health Organization (WHO) 2019.[2] The histopathologic differential diagnosis of papillary lesions, which presents a wide spectrum of entities, requires careful examination.[3] Focal or complete loss of myoepithelial cells and the ratio of neoplastic epithelium cannot be easily determined with core biopsy.[4] FNAC has been suggested as a first-line, minimally invasive method for the diagnosis of breast lesions.[5] However, identification of papillary lesions with FNAC is an especially problematic and controversial issue. Overlapping cytological features between papillary lesions of the breast and other breast lesions makes diagnosing breast papillary lesions even more challenging with FNAC.[6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] Thus, breast papillary lesions were classified in the gray zone in cytology classification systems (atypical/indeterminate and suspicious/probably malignant breast lesions, NCI (National Cancer Institute) 1996[12]; code 3—atypical, probably benign; and code 4—suspicious, probably malignant, IAC (International Academy of Cytology-Yokohama) 2016[13]).

In our study, we reviewed all breast aspirates from 2010 to 2020 that were reported as papillary lesions. The first aim of this study is to investigate the diagnostic accuracy of FNAC in differentiating papillary lesions from other breast lesions. The second aim is to investigate the diagnostic accuracy of FNAC in cases with diagnosed papillary lesion to differentiate benign or malignant. Also, we re-assessed the cases that were misdiagnosed in both stages.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In our center, FNAC is performed by an experienced radiologist under ultrasound guidance, with rapid on-site evaluation by a pathologist. Cell block is prepared from the aspiration material. If necessary, immunohistochemical markers (CK5/6, CK14, heavy-chain myosin, calponin, and p63) are used to indicate the presence of myoepithelium and/or nature of proliferation of the epithelium. All cases are examined by two experienced pathologists in breast cyto/histology. In our center, breast FNAC samples are classified as unsatisfactory, benign (category I), atypical/probably benign (category II), atypical—not otherwise specified (NOS) (category III), atypical/probably malignant (category IV), and malignant (category V). The criteria we used in classification are summarized below. According to NCI 1996[12] and IAC 2016,[13] we separate the “atypical” and “suspicious” groups into three subcategories of atypical/probably benign, atypical—NOS, and atypical/probably malignant.[14] The triple test (clinical, radiological, and cytological findings) are applied to all our cases.[15]

Cases are classified according to the following cytological criteria:

Category I: Benign: Lesions with no specific cytological diagnosis but with benign cytological features (flat sheets of myoepithelial cells, apocrine metaplasia and foam cells, paucity of papillary structures, and no atypia), duct-related/cystic lesion in radiology, and evaluated in favor of IP or primarily considered IP. We recommend clinical/radiological correlation for this category.

Category II: Atypical—probably benign: Cellular, three-dimensional papillary clusters with fibrovascular cores or flat sheets of myoepithelial cells, cuboidal or columnar cells, apocrine metaplasia and foam cells, and duct-related/cystic lesion in radiology. Lesions that are considered primarily IP, other proliferative breast lesions, and AIP were not excluded in the differential diagnosis. We recommend clinical/radiological correlation and follow-up for this category

Category III: Atypical—NOS: Moderately to highly cellular, three-dimensional papillary clusters with fibrovascular cores or flat sheets, sparse/absent myoepithelium in some cell groups, cuboidal or columnar cells, focal low-/intermediate-grade cellular atypia, and may be apocrine metaplasia and foamy cells. Differential diagnosis includes AIP, DCIS-P, and EPC, due to low/intermediate atypia and sparse/absent myoepithelium. We recommend tru-cut biopsy or total excision for this category.

Category IV: Atypical—probably malignant: Highly cellular, sparse papillary clusters and cribriform/tubular architecture, monomorphic cell groups, cell balls, small–large dyshesive cell groups, numerous isolated cells, tall columnar cells, many naked nuclei but no bipolar cells, intermediate/severe cytologic atypia (including nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli), and blood and hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Lesions with malignant cytological features but not definitive malignancy, with a predominantly malignant papillary neoplasm (EPC, SPC, IPC, IDC-P (invasive ductal carcinoma on the IP background), and IDC-extensive DCIS). We recommend total excision.

Category V: Malignant: Highly cellular, cell balls/papillary structures without core, a large number of isolated cells, small–large dyshesive cell groups, tall columnar cells, irregular nuclear membranes, prominent hyperchromasia, and pleomorphism. No oval bare cores with myoepithelial origins. Neoplasms (EPC, SPC, IPC, IDC-P, and IDC-extensive DCIS) with definitive malignant cytological features and showing papillary configuration. We recommend definitive therapy.

We selected 346 cases that were diagnosed as papillary lesions among 5112 breast FNAC results from 4958 patients between 2010 and 2020 from the database of Haydarpasa Numune Education and Research Hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. A total of 139 excised cases out of the aforementioned 346 cases were included in this study.

In the first stage, histopathologic examination and cytology results of 139 papillary lesions were compared. In the next stage, cases confirmed as papillary lesions with histopathology were included in the statistical analysis. During the calculation of the values, “category I” and “category II” were interpreted as “benign group” and “category III,” “category IV,” and “category V” were interpreted as “malignant group.” Overall accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, PPV, and NPV were calculated. Only cases whose cytology and histopathology results were discordant were re-examined. The cytological criteria and clinical and radiological findings in papillary lesions are also summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cytological, clinical, and radiological features in differentiation of benign/malignant papillary lesions

| Cytological features | Cytological diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Benign | Atypical—probably benign | Atypical—NOS | Atypical—probably malignant | Malignant | |

| Cellularity | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Papilla with fibrovascular core | + | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| Columnar cells | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Myoepithelial cells | ++ | +++ | ++ | +/- | - |

| Cohesive groups | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Proteinaceous background | ++ | +/- | -/+ | - | - |

| Apocrine metaplasia | + | +++ | ++ | + | - |

| Foamy histiocytes | + | +++ | ++ | - | - |

| Pleomorphic nucleus | - | - | + | ++ | +++ |

| Bloody background | - | -/+ | +/- | ++ | +++ |

| Hemosiderin-loaded macrophages | - | - | +/- | ++ | +++ |

| Single cells, “cell balls” Clinical/radiological features |

- | - | - | ++ | +++ |

| Old age | - | - | -/+ | + | + |

| Ductus-related lesion/cystic | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | + |

| Semisolid/solid lesion | - | - | + | ++ | +++ |

| Cytological differential diagnosis | More IP | IP, AIP not excluded | More AIP, DCIS-IP, and EPC not excluded | EPC favor SPC, IPC not excluded | More SPC, IPC favor |

-: absent, +: mild/few, ++: moderate, +++: marked/severe/many

RESULTS

The patients’ ages ranged between 17 and 84 years, with a mean age of 52 years; 99.3% of the patients (138 patients) were female and 0.7% (1 patient) was male. The diameters of the lesions ranged 0.5–8 cm, with an average lesion diameter of 1.7 cm. The diagnosis of a papillary lesion was supported by radiological imaging (retroareolar localization, cystic nature, and association with duct) in 57 (41.6%) of the cases. The list of histologic diagnosis of 139 surgically excised cases (including excisional biopsy, lumpectomy, or mastectomy) and their comparison with FNAC results are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of the histopathologic diagnoses of the cases that were diagnosed as papillary lesions with FNAC according to cytological categories

| Cytological diagnosis | Histologic diagnosis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| IP | PFC-P | AIP | DCIS-P | IDC-P | EPC | SPC | IPC | IDC-DCIS | IDC | TC | FA | Follow-up n (%) | Total n | |

| Benign | 18 | 6 | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | 1* | _ | 10 | 35 (19) | 183 |

| Atypical—probably benign | 28 | 6 | 1 | 1a | 1* | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | 1 | 8 | 46 (55) | 83 |

| Atypical—NOS | 6b | 2b | 2b | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 28 (74) | 38 |

| Atypical—probably malignant | _ | 1b | 1b | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | _ | 6 | 5 | _ | _ | 19 (76) | 25 |

| Malignant | _ | _ | _ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | _ | _ | 11 (66) | 17 |

| Total (n) | 52 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 21 | 139 (40) | 346 |

IP: Intaductal papilloma; PFC-P: proliferative fibrocystic changes and papillomatosis; AIP: atypical intraductal papilloma; DCIS-P: ductal carcinoma in situ arising IP; IDC-P: invasive ductal carcinoma arising IP; EPC: encapsulated papillary carcinoma; SPC: solid papillary carcinoma; IPC: invasive papillary carcinoma; IDC-extensive DCIS-P: invasive ductal carcinoma-extensive papillary ductal carcinoma in situ; IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma; TC: tubular carcinoma; FA: fibroadenoma. *Sampling error, afalse negative, bfalse positive

Diagnosis of papillary lesion was confirmed by histopathology in 103 (74.1%) of 139 cases [Figure 1]. One case that previously diagnosed “papilloma” (category II) was finally diagnosed as IDC developed in the background of IP. This case was evaluated as sampling errors and excluded from the statistical analysis. The remaining 35 non-papillary cases were listed as follows: 21 FA cases (category I: 10 cases, category II: 8 cases, category III: 3 cases); 12 IDC-NOS cases (category I: 1 case, category III: 3 cases, category IV: 5 cases, category V: 3 cases); and 2 tubular carcinoma (TC) cases (category II: 1 case, category III: 1 case). One of these cases diagnosed “in favor of IP” (category I) was finally diagnosed as IDC-NOS with extensive papillomatosis and evaluated as sampling error. Other cases were evaluated as interpretation error [Figure 2b, c, d].

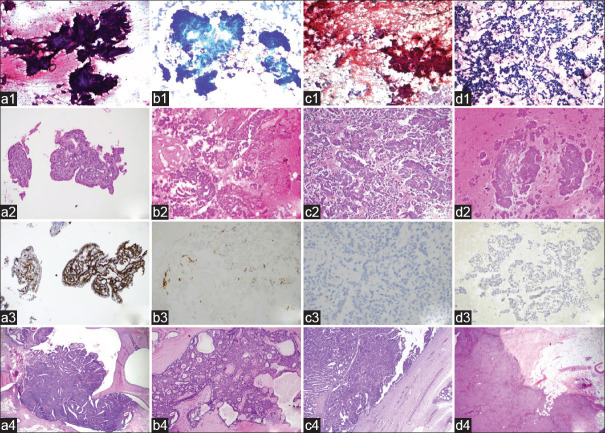

Figure 1.

a: Intraductal papilloma: three-dimensional papillary fragment of epithelial cells, papanicolaou (PAP) x200 (a1); papillary structure in the cell block, H and E x200 (a2); positive staining with CK14, IHC x200 (a3); tissue section showing the intraductal papillary proliferation, H and E x40 (a4). b: Papillary ductal carcinoma in situ: crowded cell groups, May Grunwald-Giemsa (MGG) x100 (b1); uniform tumor cells overlying papillary structures H and E x100 (b2); foci with loss of myoepithelial in cell block shown with CK14, IHC x100 (b3); monotonous cell foci within the papilloma in the resection material, H and E x100 (b4). c: Encapsulated papillary carcinoma: hypercellular aspirate, large papillary structures, and individually dispersed atypical cells, some of which show columnar morphology, papanicolaou x100 (c1); well-formed papillary structures in cell block H and E x100 (c2); absence of basal layer staining with p63 in encapsulated papillary carcinoma consisting of monoclonal proliferation, IHC x200 (c3); tumor tissue completely surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule, H and E x100 (c4); d: Solid papillary carcinoma: cell groups consisting of a few cells, some of them columnar, showing significant loss of cohesion in the ground, MGG x40 (d1); three-dimensional papillary cell groups of varying sizes in the cell block, H and E x100 (d2); monotonous appearance with CK5/6, IHC x200 (d3); well-circumscribed, solid tumor in resection material H and E x100 (d4)

Figure 2.

a: Proliferative fibrocystic changes and papillomatosis: Three-dimensional, cohesive, benign ductal epithelial cell clusters in papillary configuration on the ground of few bipolar bare-nucleated myoepithelial cells, PAP x40 (a1); apocrine metaplastic cell groups and foamy histiocytes, PAP x40 (a2); proliferative fibrocystic changes (papillomatosis, apocrine hyperplasia, and moderate epithelial hyperplasia and microcysts) in resection specimen H and E x100 (a3). b: Fibroadenoma with epithelial hyperplasia: hypercellular aspirate PAP x100 (b1); cohesive benign ductal epithelium clusters with three-dimensional papillary configuration PAP x100 (b2); florid epithelial hyperplasia focus in typical FA in tissue section H and E x100 (b3). c: Tubular carcinoma: cohesive, large and small, monotonous-looking epithelial clusters and cells showing loss of cohesiveness on the ground PAP x40 (c1); monotonous cell groups forming papilla-like structures, tubules, clefts in the cell block H and E x200 (c2); carcinoma consisting of well-formed glandular structures, with diffuse protrusions on the apical surface of the cytoplasm, H and E x100 (c3). d: Invasive ductal carcinoma on the background of papilloma: hypercellular aspirate. Numerous clumps of adherent and three-dimensional epithelial clusters, as well as atypical cells, most of which are individually shed and isolated PAP x200 (d1); papillary structures and dyshesive cells in the cell block H and E x100 (d2); surgical follow-up invasive ductal carcinoma with ductal carcinoma in situ H and E x100 (d3)

We examined the accuracy and reliability of FNAC to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions in the 103 cases confirmed with histopathologic examination. Sixty cases were classified in the benign group (category I and II), and 43 cases were classified in the malignant group (category III, IV, and V) with FNAC. In all, 59 of the 60 cases were confirmed as benign papillary breast lesions in the histopathologic examination. One case (1/60) was diagnosed as DCIS-P in the histopathologic examination and thus was reclassified in the malignant group. This case was assessed as a false negative (FN). In all, 31 of the 43 cases were confirmed as malignant papillary breast lesions in the histopathologic examination. The remaining 12 cases (12/43) were reclassified into the benign group: 2 of the cases (category IV) were histologically diagnosed as PFC-P and AIP, and 10 cases (category III) were diagnosed as IP (6 cases), PFC-P (2 cases), and AIP (2 cases), respectively. These cases were assessed as false positives (FP). Cytological and histopathologic correlations of benign and malignant papillary lesions are listed in Table 3. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of FNAC in classifying papillary lesions into benign and malignant groups were calculated as 87%, 97%, 83%, 72%, and 98%, respectively.

Table 3.

Correlation of diagnosis by cytology and histopathology

| Cytological diagnosis | Histopathologic diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Malignant (n) | Benign (n) | Total (n) | |

| Malignant group | 31 | 12** | 43 |

| Benign group | 1* | 59 | 60 |

| Total | 32 | 71 | 103 |

*False negative, **false positive

Cell blocks were obtained in 101 of the cases. Of 29 cases with optimal cell block, 2 cases were in category I, 5 cases were in category II, 6 cases were in category III, 12 cases were in category IV, and 4 cases were in category V. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was applied in 24 of these cases. It contributed to the diagnosis in 22 cases.

DISCUSSION

To recognize papillary lesions

Papillae, which are characterized by epithelial cell proliferation surrounding the fibrovascular core, are characteristic diagnostic features of papillary breast lesions. Accurate diagnosis of breast papillary lesions by FNAC is problematic due to overlapping cytological features.[6,7] Papillary-like architecture that mimics papillary structure can be observed in other benign and malignant breast lesions.[6,7] In addition, papillary lesions can be seen together with many other breast lesions [Figure 2a1, a2, a3].[13] Cytological diagnosis of papillary lesions is difficult, and the sensitivity and specificity are both low. Papillary neoplasms cannot be distinguished, even in retrospective studies.[15] In our study, FNAC-based papillary lesion diagnoses were histopathologically confirmed for 103 of 139 (74.1%) cases. The diagnostic accuracy of FNAC for papillary lesions in the literature varies between 27% and 88%.[6,7,9,10] The reason for the aforementioned difference between the reported accuracy rates of FNAC might be explained by the ambiguity of papillary lesion diagnosis criteria and lack of clear definition of the nature of the papillary fragment.[16,17] It has been reported that the incidence of papillary fragments in cases diagnosed with papilloma varies between 42%[7] and 72%.[6] True papillary fragments are considered to be the most widespread diagnostic feature.[8,10] Field et al.[17] emphasized that a “true” papillary fragment is not frequently observed in papillomas (21%). Besides, it is not required for diagnosis of a papilloma. Field also identified meshwork and stellate tissue fragments as the most diagnostic cytological criteria. A proteinaceous background containing macrophages and siderophages and the association of apocrine cell layers with at least one of the aforementioned features are reported as indicators.[18] In our series, 25.2% of cases were not diagnosed as papillary lesions according to the histopathologic examination. In a similar way, Simsir et al.[6] and Nayar et al.[8] could not verify 54% of cases and 40% of cases in the histopathologic examination, respectively.

Fibroadenoma and intraductal papilloma can be distinguished easily with histologic examination, but these entities might be misdiagnosed with FNAC because of several overlapping features.[6,7,18] Even though both the lesions are benign, distinguishing papillary lesion from FA is required for avoiding an unnecessary surgical excision.[8,17,19] Cohesive cells, branching tissue fragments, fibromyxoid fragments, and myoepithelial cells are common in both lesions. A cystic background, foamy histiocytes, and apocrine metaplasia indicate papilloma, but these features can also be seen in FA. Branching fragments of fibroadenoma may include a fibrovascular core and columnar cells. It is reported that FA is mistaken as a papillary lesion with FNAC in between 14% and 75% of cases.[7,8] Also in our study, 21 papillary lesions according to FNAC were diagnosed as FA in the histopathologic examination (15%) [Figure 2b1, b2, b3]. Eighteen of 21 FA cases were classified into two categories (categories I and II). Typical cytological criteria for the diagnosis of FA were not observed in FNAC in these cases. When reassessed, branching tissue fragments, columnar cells, and papilla-like structures might have led to a misdiagnosis of IP in our series. In addition, extensive fibrocystic changes (FCD) and ductal ectasia (DE) accompanying FA in nine of these cases may be a factor in misinterpreting the lesion as papillary lesion. In the other three cases; the presence of columnar cells, apocrine metaplasia, and foamy cells, as well as a large number of epithelial cell groups in which myoepithelial cells were not clearly observed, caused them to be included in category III.

Twelve IDC-NOS cases were misdiagnosed as papillary lesions with FNAC in our study. In the resection specimens, diffuse papillomatosis and florid epithelial hyperplasia were seen around the tumor in 1 of 12 cases, which was accepted as sampling error. Three misdiagnosed cases were in category III. FNAC showed hypercellular, papillary structures and crowded clusters, as well as cribriform and papillary structures. Histopathologic examination revealed IDC-NOS containing mucinous components in two cases. Mucinous carcinomas are lesions that can be misdiagnosed as papillary neoplasms.[7,20] Papilla-like structures caused the lesions to be incorrectly evaluated as papillary lesions in six of the cases (categories IV and V). In a similar way, the plasmacytoid appearance of the two remaining cases caused them to be misdiagnosed as papillary lesions [Figure 2d1, d2, d3].

TC is most frequently confused with FA, but it can also be misdiagnosed as a papillary lesion.

In the absence of specific findings (e.g., tubules, clefts) for TC in FNAC, monotonous columnar cells may lead to misdiagnosis of the lesion as papillary neoplasm.[18,21] In our study, two cases (categories II and III) were diagnosed as TC in the histopathologic examination [Figure 2c1, c2, c3]. Foamy cells, columnar cells, and cohesive epithelial cell clusters of varying sizes and some with papillary configuration were observed in one case classified as category II. In the histopathologic examination, this case was diagnosed as multifocal tubular carcinoma. Widespread columnar cell alterations and sclerosing adenosis were identified in or around the tumor. In the other case, papillary structures, columnar cells, and atypical groups without myoepithelial cells were observed. Papillary structures were also observed in the cell block. In this case, cribriform DCIS and FA accompanying tubular carcinoma were observed in the histopathologic examination.

To differentiate benign/malignant

Distinction of breast papillary lesions as benign or malignant is one of the most encountered difficulties in diagnosis with FNAC.[6] Benign papillary lesions contain luminal secretory cells and basal myoepithelial cells. Malignant transformation is the result of loss of dual differentiation.[22,23] Distinction of benign or malignant differentiation with FNAC is not an easy task. There are some studies in the literature to identify suitable criteria for this. Fibrovascular core, columnar cells, apocrine metaplasia, and number of bipolar naked nuclei are required for a diagnosis of papilloma. Findings that distinguished papillary carcinoma from IP are high cellularity, more complex papillary architecture, low–intermediate-grade nuclear atypia, single papilla (cell ball), isolated columnar, plasmacytoid cells, and macrophages containing hemosiderin. Bipolar cells and apocrine cells are not present in the background in papillary carcinoma. Also, none of these features alone are pathognomonic [Figure 1].[6,7,10,24,25,26]

Some authors have reported that the specificity and sensitivity of FNAC are low in distinguishing papilloma and papillary carcinoma; thus, biopsy or excision is required for a definitive diagnosis.[6,7,9,10,11,16,17,24] The same is also true for histopathology.[10] The method of core biopsy has been more prevalently used in the last years, and it allows the use of IHC markers, thus leading to a more accurate diagnosis of the lesion.[3,22] IHC can also be applied in FNAC and thus also contributes to the diagnosis just like core biopsy. This method is generally successful in specimens with high cellularity, but IHC does not always contribute to the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant papillary lesions.[23] Nevertheless, even with the application of IHC markers, it is suggested that core biopsies may lead to significant amounts of false positive and false negative diagnoses, as well as finally leading to full excision of the papillary lesion.[27,28] In our study, cell blocks were obtained from 101 cases, and these blocks contributed to the diagnosis of 29 cases. IHC was applied in 24 of these cases [Figure 1 a3, b3, c3, d3]. Tse,[28] Hatada,[29] and Caruso[30] reported that core biopsy is more useful than FNAC. However, Masood[4] reported that FNAC is superior to core biopsy in the diagnosis of papillary lesions and differentiation of benign/malignant papillary lesions. The overall accuracy for FNAC and core biopsy is 80.5% and 72.7%, respectively, in their study. The comparison of FNAC/core biopsy accuracy rates is reported as 85.7%/83.3% for benign lesions, 70%/50% for atypical lesions, and 80%/100% for malignant lesions, respectively.[4] As a result, the diagnostic difficulties encountered in core biopsies are similar to those in FNAC.[23,31]

In our study, one case diagnosed as “papilloma” (category II) was histopathologically confirmed as DCIS-P. This case was false negative. Papillary-like structures and foamy histiocytes were observed in FNAC and in cell blocks. DCIS in IP background was observed in the resection specimen. This case was accepted as an interpretation error. Twelve cases were assessed as false positives. Two cases that were classified as category IV with FNAC turned out to be benign papillary lesions histologically. Three-dimensional cell groups without myoepithelial and atypical single cells were observed; therefore, in situ/invasive breast cancer developing on the papillary lesion was considered in the cytological diagnosis of the first case. Extensive sclerosing papilloma and proliferative fibrocystic changes were observed in the resection specimen. In the other case, foamy histiocytes, three-dimensional crowded clusters, papillary structures, and atypical cell groups without myoepithelium were seen with FNAC, and sparse p63 and CK5/6 staining were detected on the cribriform/papillary structures in the cell block. EPC or DCIS-P was considered cytologically. Definitive diagnosis was reported as AIP. The remaining 10 false positive cases have been classified in category III by FNAC. In summary, 12 cases were evaluated as interpretation errors.

We use category III in cases where we cannot comment on the benign/malignant distinction according to cytological findings in our institution for breast lesions. As a matter of fact, 10 (48%) of 21 papillary lesions in this category were diagnosed as benign and 11 (52%) as malignant papillary lesions in the histopathologic examination. However, in category II, where we evaluated the cases in favor of benign, 97% (35/36) of the cases were benign; in category IV, which we evaluated in favor of malignancy, 85.7% (12/14) of the cases were confirmed as malignant. In categories I and V, the diagnosis of benign and malignant was confirmed in all cases.

In our study, the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of FNAC in differentiation of benign and malignant papillary lesions were determined to be 87%, 97%, 83%, 72%, and 98%, respectively. When the literature is reviewed, few studies are seen. In Table 4, the data of these studies along with our study are presented. Our results seem to be in agreement with other studies.

Table 4.

Summary of studies (excluding non-papillary lesions)

| Study | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive | Negative predictive value | Total cases (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Şimşir et al. | 94 | 100 | 93 | value | - | 32 |

| Jajaram et al. | 70 | 63 | 78 | 77 | 78 | 50 |

| GMKet al. | 67 | 63 | 83 | 63 | 65 | 34 |

| Prathiba et al. | 36 | 46 | - | 63 | - | 14 |

| Our study | 87 | 97 | 83 | 72 | 98 | 103 |

In summary, the role of FNAC has recently been challenged by core biopsies, which have more accurate overall results, and therefore FNAC has lost popularity in many countries. The IAC aims to promote the reuse of FNAC in breast lesions by recommending the Yokohama System.[13]

In our institute, breast FNAC has been used as a part of cytology practice for more than 25 years.

We focused on papillary lesions in our study, which have been most difficult for us to diagnose among breast lesions. The reason why we evaluated papillary lesions in five categories was to differentiate the definite benign and malignant cases and narrow the atypical group as much as possible. In our study, the diagnostic accuracy of FNAC for both distinguishing papillary lesions from other breast lesions (74.6%) and distinguishing benign and malignant lesions (87%) is clinically valuable. We suggest that the presence of true papillary structure is important in the diagnosis of papilloma. Otherwise, papillary-like structures may cause misdiagnosis. Papillary structures covered with columnar cells and the presence of spherical papillae (cell balls) are also valuable criteria in the diagnosis of malignant papillary lesions. In our opinion, FNAC can be used as a successful method in the diagnosis of papillary breast lesions with the cooperation of an experienced pathologist and radiologist. Adequate cell blocks obtained during FNAC may contribute to the diagnosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen PP, editor. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Rosen's breast pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WH Classification of Tumors Editorial Board. Breast tumours. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Lyon (France): 2019. WHO Classification of Tumours Series. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakha EA, Ellis IO. Diagnostic challenges in papillary lesions of the breast. Pathology. 2018;50:100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masood S, Loya A, Khalbuss W. Is core needle biopsy superior to fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of papillary breast lesions? Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:329–34. doi: 10.1002/dc.10251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field AS, Raymond WA, Schmitt FC. The International Academy of Cytology Yokohama System for reporting breast fine needle aspiration biopsy cytopathology. ActaCytol. 2019;63:257–73. doi: 10.1159/000501055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simsir A, Waisman J, Thorner K, Cangiarella J. Mammary lesions diagnosed as “papillary” by aspiration biopsy: 70 cases with follow-up. Cancer. 2003;99:156–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Micheal CW, Buschmann B. Can true papillary neoplasms of breast and their mimickers be accurately classified by cytology? Cancer. 2002;96:92–100. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayar R, De Frias DV, Bourtsos EP, Sutton V, Bedrossian C. Cytologic differential diagnosis of papillary pattern in breast aspirates: Correlation with histology. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5:34–42. doi: 10.1053/adpa.2001.21477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tse GM, Ma TK, Lui PC, Ng DC, Yu AM, Vong JS, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of papillary lesions of the breast: How accurate is the diagnosis? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:945–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.057489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez VA, Mayayo E, Azua J, Arraıza A. Papillary neoplasms of the breast: Clues in fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 2002;13:22–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2002.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prathiba D, Rao S, Kshitija K, Joseph LD. Papillary lesions of breast-An introspect of cytomorphological features. J Cytol. 2010;27:12–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.66692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The uniform approach to breast fine-needle aspiration biopsy. National cancer institute fine-needle aspiration of breast workshop subcommittees. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:295–311. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(1997)16:4<295::aid-dc1>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrew S, Field A, Fernando S, Philippe V. IAC standardized reporting of breast fine-needle aspiration biopsy cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:3–6. doi: 10.1159/000450880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aker F, Gümrükcü G, Onomay BÇ, Erkan M, Gürleyik G, Kiliçoğlu G, et al. Accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of breast cancer a single-center retrospective study from Turkey with cytohistological correlation in 733 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:978–86. doi: 10.1002/dc.23380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papeix G, Zardawi IM, Douglas CD, Clark DA, Braye SG. The accuracy of the ’triple test’ in the diagnosis of papillary lesions of the breast. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:41–6. doi: 10.1159/000334391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayaram G, Elsayed EM, Yaccob RB. Papillary breast lesions diagnosed on cytology. Profile of 65 cases. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:3–8. doi: 10.1159/000325674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field A, Mak A. The fine needle aspiration biopsy diagnostic criteria of proliferative breast lesions: A retrospective statistical analysis of criteria for papillomas and radial scar lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:386–97. doi: 10.1002/dc.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field A, Mak A. A prospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of cytological criteria in the FNAB diagnosis of breast papillomas. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:465–75. doi: 10.1002/dc.20653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nina SS, Fouad IB, Fadi WA. Indeterminate and erroneous fine-needle aspirates of breast with focus on the ’true grayzone’: A review. ActaCytol. 2013;57:316–31. doi: 10.1159/000351159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haji BE, Das DK, Al-Ayadhy B, Pathan SK, George SG, Mallik MK, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytologic features of four special types of breast cancers: Mucinous, medullary, apocrine, and papillary. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:408–16. doi: 10.1002/dc.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cangiarella J, Waisman J, Shapiro RL, Simsir A. Cytologic features of tubular adenocarcinoma of the breast by aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:311–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosunjac MB, Lewis MM, Lawson MT, Cohen C. Use of novel marker, calponin, for the myoepithelial cells in fine needle aspirates of papillary breast lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;23:151–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200009)23:3<151::aid-dc2>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masood S, Lu L, Assaf-Munasifi N. Application of immunostaining for muscle specific actin in detection of myoepithelial cells in breast fine needle aspirates. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;13:71–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840130115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi YD, Gong GY, Kim MJ, Lee JS, Nam JH, Juhng SW, et al. Clinical and cytological features of papillary neoplasms of the breast. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:35–40. doi: 10.1159/000325892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson AE, Mulford DK. Benign versus malignant papillary neoplasms of the breast. Diagnostic clues in fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boin DP, Baez JJ, Guajardo MP, Benavides DO, Ortega ME, Valdés DR, et al. Breast papillary lesions: An analysis of 70 cases. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:461. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tse GM, Tan PH, Lacambra MD, Jara-Lazaro AR, Chan SK, Lui PC, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast--accuracy of core biopsy. Histopathology. 2010;56:481–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tse GM, Tan PH. Diagnosing breast lesions by fine needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy: Which is better? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0962-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatada T, Ishii H, Ichii S, Okada K, Fujiwara Y, Yamamura T. Diagnostic value of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy, core-needle biopsy, and evaluation of combined use in the diagnosis of breast lesions. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:299–303. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caruso ML, Gabrieli G, Marzullo G, Pirrelli M, Rizzia M, Sorino F. Core biopsy as alternative to fine-needle aspiration biopsy in diagnosis of breast tumors. Oncologist. 1998;3:45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simsir A, Cangiarella J. Challenging breast lesions: Pitfalls and limitations of fine-needle aspiration and the role of core biopsy in specific lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:262–72. doi: 10.1002/dc.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]