Abstract

The ability to successfully manage disasters is a function of the extent to which lessons are learned from prior experience. We focus on the extent to which lessons from SARS/MERS have been learned and implemented during the first wave of COVID-19, and the extent to which the source affects governance learning: from a polity's own experience in previous episodes of the same disaster type; from the experience of other polities with regard to the same disaster type; or by cross-hazard learning - transferring lessons learned from experience with other types of disasters. To assess which types of governance learning occurred we analyze the experience of four East Asian polities that were previously affected by SARS/MERS: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong-Kong. Their experience is compared with that of Israel. Having faced other emergencies but not a pandemic, Israel could have potentially learned from its experience with other emergencies, or from the experience of others with regard to pandemics before the onset of COVID-19. We find that governance learning occurred in the polities that experienced either SARS or MERS, but not cross-hazard or cross-polity learning. The consequences in the 5 polities at the end of the first six months of Covid-19, reflected by the numbers of infected and deaths, on one hand, and by the level of disruption to normal life, on the other, verifies these findings. Research insights point to the importance of modifying governance structures to establish effective emergency institutions and necessary legislation as critical preparation for future unknown emergencies.

1. Introduction

The best means to mitigate the effects of disasters is to prepare for them in advance [1]. As large-scale disasters are high-impact but relatively infrequent events the ability to mitigate the effects of disasters is largely a function of the extent to which lessons are learned from the limited prior experience [2]. Many studies have sought to assess the lessons that may be gleaned from various disasters [3] for example). It is through this learning prism that we examine the management of the early stages of the Covid-19 crises in five polities, four of whom had previously experienced pandemics (SARS/MERS), and one which had not.

There are three possible sources from which a polity can learn and thus improve its disaster preparedness. The first is from previous episodes of the same disaster type, which may have occurred years earlier [4]. The second is from the experience of other polities with regard to the same type of disaster. The third is transferring lessons learned from successful experience coping with other types of disasters to the disaster at hand [5]. Such cross-hazard learning is the basis of the often touted All Hazards Approach [60].

In this paper we ask to what extent these three types of learning have occurred with regard to COVID-19. That is, to what extent learning occurred as a result of past experience with pandemics, and whether countries learned from the pandemic experience of others, or from their own experience with other types of emergencies.

Disaster preparedness requires multi-level multi-party governance structures, as successful crisis management requires an agile, well-prepared institutional structure, where the responsibilities and authority are well defined through appropriate legislation [6]. We thus refer to a specific type of policy learning - governance learning, which we define loosely following Newig et al. [7] as reflexive updating of beliefs on the basis of evidence, experience and new information regarding governance structures. Such learning is not limited to lived or witnessed experience, to which most policy learning studies refer, but rather to reflexive learning following a sometimes distant experience. Surprisingly, while disaster management studies often tout policy learning, due to the infrequency of events, they have only recently began looking at such learning from a comparative perspective [8].

To address the questions to what extent has governance learning occurred with regard to COVID-19, and whether it was limited to learning from previous pandemics in the same polity or benefitted from cross-country or cross-hazard learning, we first focus on the responses to COVID-19 of four East-Asian polities that were previously directly affected by SARS or MERS - South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong-Kong.1 We then compare the experience of these polities with the response of Israel, which was not affected by SARS/MERS, but has faced other major emergencies, and thus could potentially learn from its own experience with other emergencies or from the experience of others with regard to pandemics before the onset of COVID-19.

All five polities are relatively small, densely populated, unitary polities, with open advanced economies. All five have complex relations with neighbors with limited, monitored points of entry. They can thus cordon themselves off relatively easily. As small polities they are typified by dense yet heterogeneous policy networks, and thus are presumably more amenable to learn and implement changes than larger polities with more levels of government [10]. By comparing the responses and preparedness of these East -Asian polities to SARS/MERS with their responses to COVID-19 we assess the extent to which they learned from experience. The comparison of their initial responses to COVID-19 to those of Israel, serves to examine the extent to which preparedness in East Asia differed from that of similar polities who could only learn from others’ experience prior to the onset of COVID-19, or from their experience in managing crises in other fields.

Our analysis focuses on the responses to the first wave of COVID-19, as these responses reflect initial preparedness levels. The numbers of infected and deaths during the first 6 months of the Covid-19 pandemic vary among the five polities significantly. Israel had the highest number of deaths among the five. When accounted per population its death rate (41.2 per million) was almost 10 times higher than that of South Korea (5.61 per million) and 150 times higher than that of Taiwan (0.29 per million). The number of infected per population was highest in Singapore (7893 per million) and Israel (4356 per million), while the other three polities had significantly lower rates of around 200 per million (as shown in Table 1 ). To assess the success of the different polities it should be realized that the first case was detected in the four East Asian polities one month earlier than in Israel and that Israel employed the harshest measures (e.g. general lockdowns) among the studied polities to combat the pandemic. Hence, the four East Asian polities were clearly more successful in containing the pandemic in its initial stages than Israel.

Table 1.

Country statistical comparisons – sars-mers and covid 19.

| Singapore | Taiwan | Hong-Kong | South Korea | Israel | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population 2020 (millions) | 5.8 | 23.8 | 7.5 | 51.3 | 8.6 | |

| Density (P/Km2) | 8,358 | 673 | 7,140 | 527 | 400 | |

| SARS cases (deaths) | 238 (33) | 346 (73) | 1,755 (299) | 3 (−) | – | |

| MERS cases (deaths)a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185 (33) | 0 | |

| Coronavirus casesb | ||||||

| Actual cases: July 11, 2020 | Total | 45,783 | 451 | 1,433 | 13,373 | 37,464 |

| Active | 3,731 | 6 | 229 | 941 | 18,269 | |

| Deaths | 26 | 7 | 7 | 288 | 354 | |

| First case diagnosed | 23 January | 21 January | 23 January | 20 January | 21 February | |

Adlhoch, Cornelia and Baka, Agoritsa and Mollet, Thomas and Plachouras, Diamantis and Brusin, Sergio and Penttinen, Pasi and Briet, Olivier. (2018). RAPID RISK ASSESSMENT Severe respiratory disease associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries (retrieve: 11/7/20).

2. Policy/governance learning for emergency management: a brief overview

Large-scale disasters are marked by their widespread impacts and low frequencies. Many of them can be described as Gray Rhinos [11]: events that occur with near-predictable (low) frequency - at time intervals that exceed the life span (and memory) of at least one generation. Many are met by surprise as if they had never happened before because in fact, for many of the current communities of the world, they never have. A major factor – and challenge – for managing these events and the extent of damage they render is the level of preparedness [12]. Emergency preparation requires having legal and institutional infrastructure in place and regularly maintained, requiring continuous budgeting to mitigate the effects of a low probability event [13]. As many governments have not experienced major disasters and continually face pressures to address the present-day demands of various interest groups, emergency readiness is a low saliency issue, unless there is an event that focuses attention on the need for effective emergency management institutions and infrastructure [14]. When they occur, disasters can serve as such focusing events, spurring governments to undertake the necessary legislative, institutional and physical infrastructure outlays [15]. Therefore, learning from the experience gained from disasters is critical for emergency readiness [2].

Policy learning, as defined by Sabatier [16]; p. 672) is “relatively enduring alterations of thought or behavioral intentions that result from experience and that are concerned with the attainment of revisions of the precepts of one's belief system.” It is defined by Dunlop and Radealli [17]; p. 359), as “the updating of beliefs based on lived or witnessed experiences, analysis or social interaction”. There are many prisms through which to examine policy learning, one of which is the origin of the source that precipitates change. According to Newig and colleagues [7] the sources of policy-learning – i.e. experiences or new information - may be endogenous, originating inside a policy field or jurisdiction, or exogenous, originating outside the policy field or jurisdiction. In this paper, we examine the relative effectiveness of endogenous learning (in those countries that experienced SARS and/or MERS) versus the Israeli experience of exogenous learning (from other countries with SARS/MERS and from its own experience dealing with other types of emergencies).

There is a broad and nuanced literature describing various policy-learning tools. For instance, policy benchmarking is a popular form of learning in which policymakers identify best policy practices, based on performance, and use those instruments and alternatives as guides [18]. In the case of COVID-19, benchmarking can be used to compare performance data across countries or regions, allowing policymakers to identify the best practices of foreign governments [19]. Several studies have addressed the technical adjustments required to effectively benchmark across regions and countries [20,21]. In the context of our study, benchmarking may have been used by the selected countries as a form of exogenous policy learning, to learn and adjust their policies during the pandemic response. However, realistically, it is unlikely that benchmarking will be used for a-priory learning and thus is less useful for our case, as we focus on policy adjustments made before the COVID-19 pandemic, as a result of the SARS and MERS epidemics, as well as adjustments made at the very beginning of the pandemic. It is more likely that countries used policy benchmarking as a form of learning once the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, in order to adjust their responses, in light of performance differences between countries.

Addressing pandemics, as other disasters, requires a mix of policy measures. In their recent international comparison, Goyal and Howlett [22] show that the intensity, density, and balance of policy mixes in the COVID-19 response is extremely varied. Mei [23] argues that success in containing the spread of COVID-19 is not a result of a specific policy-mix, but the extent to which the policy-mix employed in the response aligns with the ingrained policy dynamics in a country. At the onset of the pandemic these are largely a result of the preparations made before. Thus, while we do not examine the full policy-mixes employed by the countries studied, the results of our analysis may help explain the differential policy-mix dynamics across the sample of countries. However, a comprehensive policy-mix analysis is beyond the scope of this study.

As successful emergency management is a function of preparedness, the most meaningful learning processes do not pertain to specific policies, but rather to the need for institutional and decision-making procedures adjustments. Therefore, we refer to the learning pertinent for the case of emergency preparedness as governance learning. Governance learning can be viewed as a special case of policy learning, as it refers to learning from infrequent distant experiences that may have not been directly lived or witnessed [7]. This is particularly true in the case of emergency management due to the wide variance in physical and societal circumstances as well as the differences among various types of emergencies [15].

While policy learning is much discussed, governance learning, particularly in the case of emergency management, receives only limited attention. Moreover, empirical studies focusing on post-emergency policy learning find that in many cases the lessons are not implemented [24] or that the learning process ends in what Birkland [25] termed ‘fantasy documents’. A question which we pose here is to what extent the source from which the lessons are learned makes a difference, if at all.

3. Methodology

This paper focuses on three possible sources from which lessons may be gleaned for coping with COVID-19: 1) prior experience of the polity with the same type of disaster (pandemic); 2) cross-hazard learning – the extent to which the expertise a polity has gained from its coping experience with other disaster types can be applied to the management of pandemics [1]; and 3) diffusion of insights – transferable learning factors - based on the experience (with pandemics) of other polities [14]. The case studies were chosen accordingly. To examine the efficacy of direct prior experience with pandemics we look at South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong-Kong (all of whom experienced SARS/MERS) and the lessons they have applied to COVID 19. For insights about cross-hazard learning we examine whether Israel has been able to adapt and transfer knowledge about its handling of security belligerencies (wars, terrorism) to the governance and management of the pandemic. And for the third source of diffusion of insights we identify critical factors for successful coping with pandemics that the East Asian countries exhibit and from which Israel (and by extension other polities without prior recent experience with pandemics) might have learned.

The countries chosen are relatively small unitary polities, with open economies, and limited points of entry that thus can easily be cordoned off. All four East-Asian polities responded well in the first months of COVID-19 [9] performing better than other countries in terms of medical (Table 1) and economic results. Despite this shared success, some of the lessons each gleaned differ as a function of their particular experience during SARS/MERS. We identify both the differences and similarities in the governance adaptations made. To analyze cross-hazard and cross-country learning we compare how the governance structures in these polities at the outset of the first wave of COVID to that of Israel, as well as the immediate responses. Israel too has an open economy, is densely populated and has very limited points of entry. Moreover, Israel has had three major emergency situations since the turn of the century. In 2006, 2008–2009, and 2014, large parts of the country were subject to widespread rocket attacks, which led to a realignment of emergency readiness institutions. Israel has good relations with all the East-Asian polities and thus is in the position to learn both from the East-Asian handling of COVID and from its own experience in emergency management. We limit our analysis to the first wave of COVID-19, as after that each polity could derive lessons from its own experience during the first wave, thereby rendering the questions of cross-polity and cross-hazard learning to secondary importance thereby limiting the ability to assess their implications.

Five factors, whose tenets we deem to be potentially adaptable were examined in each country: 1) Initial response and disease control measures – the extent to which they are information driven, differentiated by the spread and impact of the pandemic, and transparent; 2) Legal context – to what extent is there a legal framework to deal with pandemics; 3) Governance structure and networks – the extent to which a statutory coordinating body with decision making authority exists and whether civil society and local jurisdictions are integrated in an effective response network [26]; 4) Information and communication – the extent to which consistent reliable information is communicated to the public and by whom; 5) Economic response– the measures taken in the case of economic slowdown or lockdown. In addition, we refer to the political setting where it affected response.

4. Lessons learned from prior experience: from SARS/MERS to COVID-19 in the East-Asian polities

SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 are coronaviruses that have crossed the species barrier to infect humans. While SARS originated in China in 2002, and impacted three of the polities studied (Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan) MERS originated in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and affected the fourth (South Korea). To examine the ways and extent to which SARS/MERS altered these countries preparedness for and handling of COVID-19, a very brief synopsis of highlights from the individual SARS/MERS experiences is noted, followed by the preparation and responses to COVID according to the five factors set out above.

4.1. Background: the East Asian polities’ prior experience

4.1.1. Hong-Kong

The SARS crisis exposed weaknesses in the ability of Hong-Kong's health system to effectively address the pandemic as it lacked adequate facilities and failed to isolate infected individuals after admission (Hung, 2003). However, daily reports from the Department of Health, hospitals and other government authorities were transparent in terms of data, accepted by the public as trustworthy, and public cooperation was high [27]. A factor that assisted Hong-Kong's response to SARS was the de-facto governance network that was employed and the level of trust in central and local government (which changed significantly in the Covid-19 era). During SARS, civil society groups took action and mobilized themselves. Grassroots initiatives were undertaken to increase societal solidarity, encourage volunteerism, collect funds for the needy, and increase local and neighborhood community support [28].

4.1.2. South Korea

South Korea's story largely contrasts with that of Hong-Kong. During SARS there were only three confirmed cases. The post-SARS policy focus was on improving the healthcare system and enhancing government-wide preparedness for future epidemics [29]. However, South Korea was one of the worst hit countries by MERS and the government response at the time was heavily criticized as secretive, lacking strategy, transparency and not providing reliable updated information to the public [30]. Subsequently, the government advanced reforms, including legal powers for quarantine and surveillance systems, development of digital technologies, and imposing obligations on the government itself during emergency response.

4.1.3. Singapore

As a city-state, Singapore has no local government. There are five Community Development Councils (CDCs) which provide local administration and community and social assistance services delegated from the national ministries. During SARS the Singapore Ministry of Health employed an official pro-active and transparent information strategy to provide a stream of information on the nature of the disease, symptoms, transmission mechanism, numbers of infections, fatalities, chances of recovery and preventive health care information, resulting in a high level of citizen satisfaction with the government's response [31]. Consequently, no structural modifications were undertaken in its aftermath.

4.1.4. Taiwan

Taiwan, like South Korea, significantly strengthened its decentralized governmental structure post SARS and MERS [32]. During SARS, civil society organizations and newly created community-actions addressed the crisis in various forms. Yet the coordination with government authorities was fragmented. Several activist organizations came together to form the “Social Security Anti-Epidemic Alliance” (SSAEA) and partnered with other civil society groups and individuals with the aim of distributing practical advice, reliable professional knowledge on the epidemics, and emotional counseling to the public [33]. These experiences prompted legal reforms which proved successful upon the Covid-19 outbreak.

4.2. Response to COVID-19: six comparative factors

4.2.1. Initial responses and disease control measures

All four polities reacted quickly to the Covid-19 pandemic (Table 2). On January 30th, 2020, the WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, but only on March 11th was COVID-19 declared a pandemic. The first responses in the four countries preceded these dates - earlier than in other countries vis-à-vis the detection of the first infected.

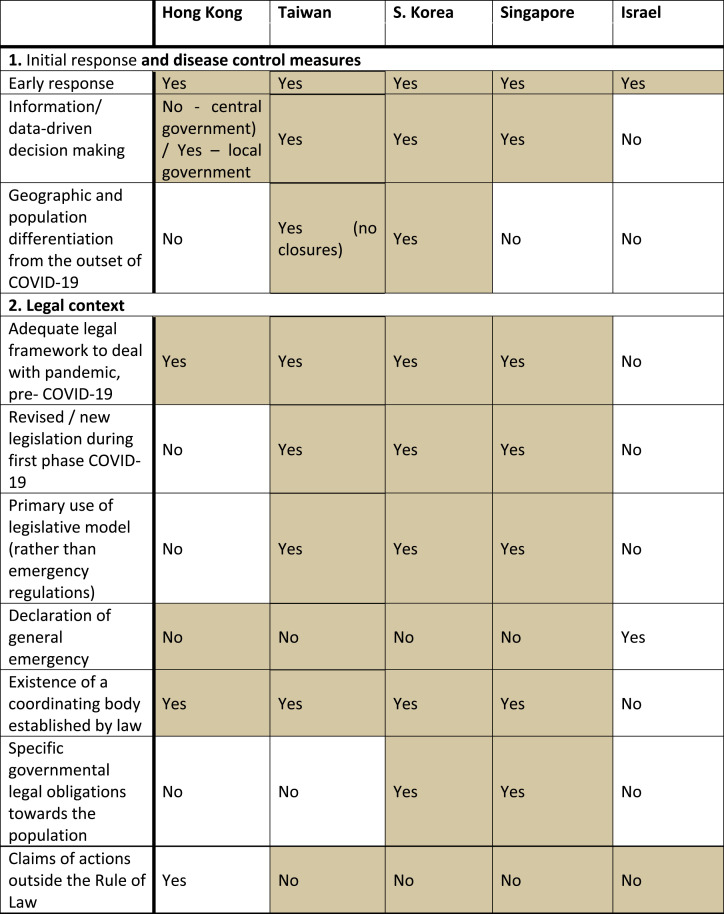

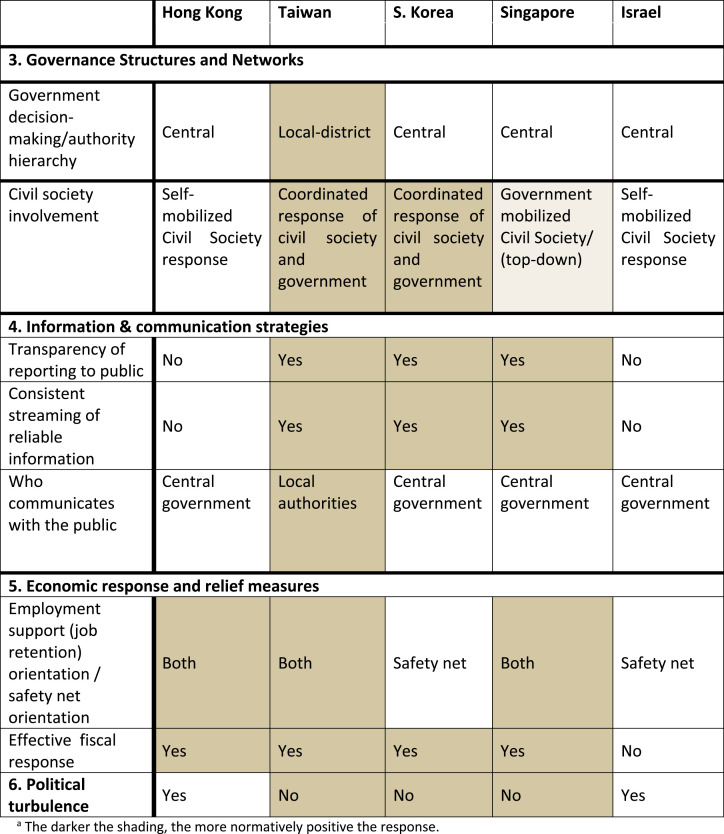

Table 2.

Comparison of fourEast-Asian polities and Israela.

The darker the shading, the more normatively positive the response.

In Hong-Kong the government resisted quick action, but following public pressure, on February 8th issued emergency regulations under the Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance (PCDO) (2008), requiring compulsorily 14 day quarantines for all persons arriving from Mainland China, Macao and Taiwan.

Taiwan added the COVID-19 virus to the list of CDC diseases on January 15; and on January 20th it opened the Central Epidemics Command Center (CECC) to manage the pandemic. The CECC, originally positioned at the third level within the hierarchy of central government, was upgraded to level 2 on January 23, following the detection of the first case of the virus in Taiwan (directly under the Minister of Health). On February 27th the CECC was upgraded to level 1, whereby the Prime Minister directs the management of the crisis.

In South Korea, the government declared a ‘yellow’ state of readiness on January 20th, following the detection of the first case. A week later the readiness level was elevated to ‘orange’ and on February 23rd to the highest level, ‘red’, which, similar to Taiwan, puts the operation of the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters under the Prime Minister [34]. The reforms advanced post MERS bore fruits with the outbreak of Covid-19. The government managed the crisis by detecting and quarantining imported cases and reducing the risk of secondary transmission [35], effectively containing the virus during the first phase of COVID-19.

Singapore banned travelers from infected countries, beginning with travelers from Hubei and China on January 29th, and extended it gradually to include all countries by March 23rd. Initially Singapore implemented a test-trace-quarantine regime with temperature tests in schools and workplaces and physical distancing guidelines. However, following an outbreak in migrant workers’ dormitories, and in contrast to the other three countries, Singapore ordered a full lockdown on April 7th which was eased by early June. The lockdown was imposed although most of the infected were in geographically defined neighborhoods (Stack 2020).

4.2.2. Legal framework

Taiwan, South Korea and Hong-Kong implemented major legal reforms following their experience with SARS/MERS. During SARS Taiwan's legislature enacted the Provisional Act for Prevention and Relief Measures for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, with a sunset clause after one year. It was replaced in 2004 by a permanent law – the Communicable Disease Control Act (CDC Act) 2004,2 which has been amended approximately ten times between 2004 and June 2019. The law includes detailed disease classification models and the establishment of a centralized disease control system [36,37].

Similarly, Hong-Kong enacted the Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance 2008,3 based on lessons from SARS. Under epidemic conditions it empowers the government to issue regulations which come into force immediately, but are tabled before the Legislative Council for 28 days of “negative vetting” [38].

Following the severe MERS outbreak in 2015, South Korea enacted the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act (IDCPA).4 This is the prime legal tool in fighting Covid-19.

Singapore was the only country among the four that did not enact a new law following SARS and MERS but rather amended existing legislation – the Infectious Diseases Act 1976. A major amendment was made in 2003, followed by approximately twenty additional amendments.5

The experience with SARS/MERS also led to quick adaptations with the outbreak of COVID-19. Three of the four polities enacted thus a second phase of legislation following the early experience with COVID-19.

Taiwan can be considered as the success story during the COVID-19 pandemic. A clear legal framework actively engaging civil society engendered social trust and solidarity [36,37]. The Special Act for Prevention, Relief and Revitalization Measures for Severe Pneumonia with Novel Pathogens was enacted on February 25th with a sunset clause of June 2021.6 Additionally, a law against increasing prices for protective equipment was enacted on February 3rd, and a law imposing fines on disobeying isolation orders on the 12th.

In South Korea the IDCPA was amended on March 3rd, criminalizing suspected patients who refuse to get tested, but also ordering officials to take necessary means to make masks available to children and the elderly, as well as imposing on the government “disinfection duty” in public places.

On April 7th Singapore enacted the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act 2020 (CTMA) to be in force for one year. It grants the executive greater powers to issue control orders to prevent the spread of corona, under the requirements that the minister must be satisfied that “the incidence and transmission of COVID-19 in the community constitutes a serious threat to public health” and that the “control order is necessary or expedient to supplement the Infectious Diseases Act and any other written law”.7 The legislation also tackles the economic crises and includes temporary relief for inability to perform contracts, and for financially distressed individuals, firms and other businesses and temporary measures concerning remission of property tax.

Hong-Kong is the exception. The main legal tool utilized is not legislation but emergency regulations under the Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance (PCDO). Such regulations were issued in the beginning of February, and more significant ones on March 29, empowering the Secretary for Food and Health to prohibit group gatherings, with no exception for political demonstrations, and closing businesses. Of the four polities Hong-Kong is the only one in which claims were made that the government operated outside the rule of law, ordering the closure of schools and other public institutions after the Lunar New Year holidays with no clear legal authorization [38].

Importantly, many countries have emergency constitutions, allowing them in times of a national emergency to declare a state of emergency, thereby granting the executive extensive powers to manage the emergency, superseding laws and violating entrenched rights. More than 100 countries around the world declared a state of emergency.8 Although, all four polities have an “emergency constitution”, none employed it, apparently because they had in place an adequate updated legal framework to manage pandemics.

4.2.3. Governance structures and networks

During both SARS and COVID-19 Hong-Kong's response was largely bottom-up. The meaningful role civil society plays in COVID-19 originates thus from their experiences during the SARS outbreak, and their doubts regarding the pandemic assessments and recommendations of national government authorities [39].

A significant change in South Korea was its move from the minimal involvement of civil society during MERS to the coordinated and cooperative response of the civil society and the government during COVID-19. Transparent governance and long-term cooperation between government and civil society were critical in inducing active civic participation in the COVID-19 control [40]. In contrast to Hong-Kong, the government enjoyed high levels of trust which were revealed in the results of the January 15th general elections - a landslide victory for the ruling Democratic/Platform alliance, a considerably better outcome than had been anticipated prior to the pandemic.9

Taiwan, like South Korea significantly strengthened its decentralized governmental structure post SARS and MERS [32]. During SARS, civil society organizations and newly created community-actions addressed the crisis in various forms. Yet the coordination with government authorities was fragmented [33]. Facing COVID-19 Taiwan moved to a coordinated and cooperative response of both civil society and the government. Taiwan has an historic urban hierarchy system based on neighborhood representation. After 2009 neighborhood representatives were empowered during emergencies (specifically health emergencies). They provide a two-way pipeline of information between the national government and citizens, and a channel for organization and supply which helped promote the “whole community approach” during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) was divided into seven offices: six regional and one border. To support the CDC, local neighborhood organs familiar with the communities, were given contact information to check in daily with home-quarantined persons and provide necessary services.

Due to the apparent success during SARS, Singapore's top-down model of mobilized civil society remained largely unchanged [41]. During both pandemics the government initiated and managed the mobilization. Kindergarten teachers and school teachers were briefed on hygiene and temperature taking by health authorities to spread the message to those under their charge and through them to their families. Advocacy on behalf of the families in need, psychosocial counseling and food delivery to the quarantined was actively assisted by formal and informal civil society organizations [34].

4.2.4. Information and communication

Managing a pandemic requires governments and the public to engage in mutually trusting relationships with a shared understanding of what is expected by both sets of actors [42]. This is a function of risk communication. When health communication is effective and reliable more positive behaviours (in terms of adhering to control measures) is expected. Failure to do so might undermine the government's pandemic responses.

Singapore government approach to risk communication during SARS was one of “defensive pessimism”, in order to keep the public alert and disciplined. In the initial period of the Covid-19 outbreak in Singapore, two communication channels were employed. The conventional media channel hosted weekly press conference by key government officials, using the same narrative of “defensive pessimism” but with two additions: first, great care was given to the multi-lingual and multi-cultural context of Singapore. Direct address is crucial for building trust in multi-cultural society such as Singapore. Second, officials openly addressed the scientific uncertainties around the virus, such as the mode of transmission, effectiveness of wearing masks, the search for a vaccine, etc. [43].

The other path of communication was digital and through social media, especially WhatsApp. A detailed summary of contact tracing was sent daily through Gov. sg account, along with other key public messages (counter-fake news and scam alerts, links to websites for credible medical and financial information, and messages to inspire community spirit and familial responsibility).

Following MERS, South Korea implemented a standard operating procedure for risk communication in public health emergencies, incorporating the risk communication protocol of the WHO and CDC. KCDC held twice-daily press conference based on this five principles procedure (be right, be first, build trust, express empathy, and promote action) [44]. Another MERS output was using Cell Broadcasting System, nationally or by local authorities, to pass on relevant messages to residents (UNDRR, 2020). In addition, the government operated a 24-hr coronavirus hotline and portal site and it managed social media channels that delivered infographics and corrected inaccurate news.

Taiwan, as mentioned previously, created after MERS a system of top-down communication through the CDC centers and bottom-up communication through the organized neighborhoods representation. Public announcement intended to educate preventive habits were broadcasted regularly.

Hong Kong, in the midst of political turmoil, communicated through official national government channels and websites but didn't gain the public trust [45,46].

4.2.5. Economic response

The measures enacted to combat COVID-19 have exacted an economic toll from all countries [47]. The economic cost of the pandemic is the outcome of the direct, mainly health-related costs, the local economic downturn due to the measures enacted (quarantines, lockdowns, limitations on mobility etc.), and the implications of the downturn on the world economy, including the economies of the countries in this study [48]. As the magnitude of the economic impacts during COVID-19 is an order of magnitude greater than during SARS/MERS, the economic responses varied from the earlier pandemics.

To mitigate the economic effects, all four polities issued early fiscal responses in February. Additional fiscal stimulus packages were promulgated by early April. While Taiwan and Singapore added one additional stimulus, South Korea added two and Hong-Kong three packages. The largest stimuli were promulgated in Singapore (42 billion USD, 12.2% of the GDP) and Hong-Kong (37 billion USD, 10% of the GDP) while Taiwan allocated 35 billion USD, constituting 5.7% of its GDP and South Korea 13 billion USD (0.8% of the GDP).10

The specific measures implemented in the four countries differed both from those that were promulgated during the SARS epidemic and from each other. South Korea largely sought to reduce the cost of conducting business by lowering taxes and water rates, subsidizing working parents and rents, and providing state-backed loans. Hong-Kong, which during the SARS epidemic used measures similar to those implemented in South Korea, during COVID-19 emphasized job retention. It subsidized salaries and generated employment in the public sector in addition to state-backed loans and special support for adversely affected industries. Singapore and Taiwan combined the two approaches, subsidizing salaries to retain jobs with deferment of taxes and support to adversely affected industries (in Singapore) and small private businesses (in Taiwan).

From an economic perspective, Taiwan is of special interest as it is the sole country of those studied whose economy and way of life has remained largely unaffected by COVID-19. Utilizing lessons from SARS it enacted an integrative policy implementing a crisis management strategy that was culturally appropriate to limit the infection rate [49]. It did not limit mobility or close businesses or schools, and yet has succeeded in retaining exceptionally low mortality and infection levels.

5. Israel's response to COVID-19: a governance perspective

Israel is a country that has faced multiple large-scale security-related emergencies. The three latest, in 2006, 2008–2009, and 2014, were widespread rocket attacks affecting the civilian population throughput the country. Following the pervasive understanding of the inadequate civilian emergency response during 2006 Second Lebanon War, the government increased the funding for the civic aspects of emergency management; enhanced the capacities, capabilities and resources of the Home Front Command (HFC) within the Israel Defense Forces and established a small national coordinating body aimed to integrate and coordinate the emergency management activities – the National Emergency Management Authority (NEMA).

5.1. Institutional and legal structures to address emergencies

Despite the long exposure of Israeli society to security threats, Israel lacks a comprehensive emergency law and failed to implement the “cross-hazards learning approach” which stresses the importance of a “transfer of learning and lessons” across disaster types [1,50]. Rather, emergency arrangements are imbedded in various laws and governmental decisions which grant powers and allocate responsibilities to numerous governmental and local agencies, with no legal designation of a coordinating body for emergency preparedness, response and recovery [51]. The two main national agencies, largely responsible for emergency preparedness (HFC and NEMA) were established following major security crises, thus demonstrating efforts to learn from experience. However, these agencies were established by government decisions, rather than being anchored in law, and thus have neither legal authorities nor legal duties, and they require compliance, if at all, of government ministries only. Nevertheless, the HFC has developed emergency procedure prototypes with and within local authorities, geared mainly towards security risks.

Although Israel did not experience a major epidemic since a Polio outburst in the 1950s epidemics were identified as part of the Comprehensive Threat Scenario [52]. Still, while NEMA annually reports to the government on the level of preparedness for each of the major risks,11 pandemics remained a low salience threat with low preparedness accordingly.12 The Israeli law regulating the prevention and management of pandemics – the Public Health Ordinance 1940, dates back to the British Mandate.

5.2. Israel's response to COVID-19: and the apparent failure of cross-hazards learning

Although several national tabletop health forums were conducted during the last decade, the risk of a pandemic has not been prioritized and the required budgetary allocations and structural changes have not been made. Consequently, Israel's Public Health Services division of the Ministry of Health has been under-staffed for decades and has no advanced data systems.

Typically, societies' initial reaction to novel crises is characterized by a high level of confusion [12]. This indeed characterized the Israeli response. Despite an early action which managed to contain the first phase of the Covid-19 outbreak, NEMA has not been involved, while the HFC and local authorities were involved only in a later stage, as subordinates to the Ministry of Health. Instead, the government instructed the National Security Council (NSC), an advisory body to the Prime Minister in foreign affairs and national security, to coordinate the management of the crises.

Similar to the four East-Asian polities, Israel was quick to initially react, using the Public Health Ordinance, 1940. On January 27 the Director General of the Health Ministry signed a decree adding COVID 19 to the list of infectious diseases. It was followed on February 2nd by a decree ordering all entrants from China to remain quarantined for 14 days. The order was subsequently extended to other Asian countries, some European countries and finally (March 8) to all entering Israel.

On March 5th the decree of the General Director of the Health Ministry was extended to prohibit mega gatherings and international conferences, and on the 15th it was significantly extended, prohibiting gatherings of more than 10 people, closing schools, universities campuses, gyms, etc. Since March 15th the government began to enact emergency regulations in accordance with section 39 of Basic Law: The Government, which empowers the government, following a declaration of emergency issued by parliament, to enact emergency regulations that may alter any law, or temporarily suspend its effect.13

The Government has issued dozens of emergency regulations aimed at preventing the spread of the epidemic,14 including closing borders, imposing lockdowns, isolating infected people, limiting public transportation, and authorizing the General Secret Service (GSS) to employ its technological capacities to locate points of contact of infected people. Governmental management of the epidemic has been top-down, led by the Prime Minister aided by the NSC and the Director General of the Ministry of Health.

Israel was under an almost general lockdown for one month (March 19 – April 19). The measures Israel took were among the most stringent of all countries (including the 4 East-Asian polities) according to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker.15 By May 4th the number of new cases of infection fell to only a few per day.

Following the regulations issued by the government temporarily restricting workplace employment to 30% and subsequently 15%, many employers were forced to fire employees or put them on unpaid leave. As of May 2020, more than a million workers had become unemployed.16

The Israeli economy re-opened on April 24th, with no clear strategy or criteria, and amidst major disagreements among government offices and confusing public guidelines. After the new government was established on May 25th, the Prime Minister nominated a Corona Cabinet headed by him, and Parliament nominated a Corona Committee to review the government actions. Concurrently, the Ministry of Justice began a process of replacing the emergency regulations with regular laws, a process that was materialized only in late July,17 much later than the special Covid-19 laws enacted by the four East Asian polities.

By the second half of June the numbers of daily infected people began to rise significantly (demonstrated in Appendix 1 which includes cross country comparative statistics),18 leading to a second lockdown. This second phase of the virus has brought strong criticism of the government's mishandling of the crisis, the economic impacts, and lockdown exit process, which is confused and lacks transparency, resulting in widespread protests. These protests were further fueled by the political crisis, as the government's actions were seen by many to be largely driven by political considerations of the Prime Minister [53].

6. The East-Asian and israeli experiences compared – what can be learned from the pandemic experience of others?

The SARS/MERS experiences helped governments of all four East-Asian polities to prepare for contingencies, by developing outbreak management plans including stockpiling of essential goods, and strengthening public health infrastructure [9]. All four polities promulgated legislation and established institutions to address pandemics. The institutional structures and strategies empowered expertise-led decision-making, resulting in effective health management during the initial phase of COVID-19, while limiting both economic losses and violations of freedoms. Still, as the pandemics differ, the polities did modify their legislation/regulations in their efforts to combat COVID-19.

The relative success of the Asian polities can be analyzed in comparison with Israel. Israel also responded quickly, but health predominated at the expense of other considerations, not least due to political considerations. Israel used emergency measures enacted by the executive branch on the basis of outdated legislation and the emergency constitution, while none of the four East-Asian polities did so. Thus, despite acting early, Israel did not have the legal and institutional structures in place to manage the crisis effectively over time.

Table 2 compares the Far-East Asia polities and Israel along six parameters: Initial response and disease control measures, legal context, governance structures and networks (government decision-making/authority hierarchy, civil society involvement), information and communication strategies, economic response, and the political setting. Those that seem superior and thus can serve as a basis for lessons to be learned and adapted by other similar states are highlighted.

As shown in Table 1, Table 2, Taiwan and South Korea responded particularly well along most parameters. The main lessons from their experiences, relative to Israel and perhaps applicable elsewhere, are multi-faceted. Perhaps the most important is that a legal structure and functioning institutions are the basis for managing crises in a coordinated, transparent, and data-based manner. These were established in the East Asian countries following SARS/MERS, but not in Israel.

In terms of disease control measures, geographic differentiation allowed Taiwan and South Korea to keep open/open up their economies while controlling the spread of the virus.

In addition to developing/strengthening these structures, the Asian polities used the time between SARS/MERS and COVID-19 to develop digital technologies for emergency phone alerts and contact tracing [6]. South Korea has been praised for quickly developing effective tools, although with some defects. The country lags in protecting personal data, and a quarantine app was found to have major security leaks [54]. Issues of privacy have been raised in Singapore as well. Despite its high-tech prowess Israel found itself without the necessary epidemiological database systems or tracking technology. For the latter it reverted to using the General Secret Service, a step that was critiqued and further decreased trust in government.

Civil society and local governance are additional success factors. Civil society in the Asian polities played a major role in reducing vulnerability and maintaining resilience. Following lessons from SARS/MERS civil society actions were coordinated with the government in Taiwan and South Korea, while in Singapore they were mobilized by government. In Israel and Hong-Kong civil society self-mobilized with no governmental support or coordination, largely due to the political crises in these two settings. The political crises and lack of transparency were also part of the failure of Hong Kong and Israel to communicate effectively with the population. In contrast, South Korea learned from its failure during MERS and provided transparent and reliable information, garnering trust, as did Taiwan and Singapore. The importance of transparency and reliability of information, lacking in Israel, is clearly demonstrated.

Economic relief packages combining both job retention and safety net orientations are more effective in averting worse economic impacts. Yet not all countries combine both. While Hong-Kong, Taiwan and Singapore did, South Korea and Israel only put in place safety net provisions, thereby increasing unemployment.

7. Conclusions

Post-SARS/MERS, the Far-East-Asian polities improved their preparedness to pandemics by enhancing their institutional, legal and physical infrastructure. They began systemically thinking in terms of contingencies; saw rapid action in coordination with experts as critical; developed technologies for testing and tracking; and understood the importance of clear, open communication and transparency. At the same time Israel focused on security-related risks and practically (rather than declaratively or symbolically) neglected the kind of capacities in public health and pandemic preparedness that East-Asian polities built post SARS/MERS, indicating that policy learning in-vivo is facilitated and enhanced by direct prior experience with a certain disaster type, rather than by cross-country or cross-hazard experience. Two of the five polities – Hong Kong and Israel – also faced the COVID-19 crisis in the midst of a major political crisis and they performed worse in the first wave than the other three, pointing to a possible conclusion that political stability is a vital element of effective response, and countries in which the government enjoys high level of trust can cope better with extreme conditions.

The adaptations undertaken by the East-Asian polities meet our definition of governance learning as reflexive updating of beliefs on the basis of evidence, experience and new information regarding governance structures. One of the features of governance learning vis-à-vis policy learning is the time that is necessary to adjust legislation and institutional structures, none of which can be emulated. Indeed in the East-Asian case the adaptations made in the years after SARS/MERS allowed a rapid and effective response to COVID-19. Despite having revamped its institutional structures following the rocket attacks Israel did not enact the legislation or institutional capacity building necessary to address a pandemic, or attempt to learn from the Far-East experience with regard to pandemics. This failure cannot be attributed to the political crisis, as governance learning could have been undertaken before the crisis began. It seems thus, that the only meaningful governance learning occurred within those polities that were affected by SARS/MERS. Moreover, such learning was a result of the critiques of their handling of previous crises. This can be seen in the case of Singapore, whose handling of SARS was seen as successful, and hence it did not deem it necessary to make any structural adjustments. Consequently, the policy mixes employed by these four polities varied as a function of their prior experience.

COVID-19 has affected the whole world. It can be expected therefore that many polities will learn from this experience and make modifications to their pandemic governance structures. Still, the policy learning differs as a function of the specific experience and conditions in each country. However, pandemics are not the only infrequent disasters that can afflict polities. Thus, polities should modify their governance structures by approving the necessary legislation and establishing effective institutions, including the mobilization of the civil society as part of their preparations for various disasters. The question is to what extent polities will indeed undertake such cross-polity and/or cross-hazard learning and prepare themselves better for other emergencies. Regrettably the evidence from this study suggests this is unlikely to happen.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements and Funding

The research was conducted at the National Knowledge and Research Center for Emergency Readiness and funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Israel.

Footnotes

Following An and Tang [9] we use the term polity, as Hong-Kong is a special administrative region of China, and group Singapore with the other East Asian polities despite the fact that geographically it is part of Southeast Asia, as it is politically economically and culturally closely aligned with the other four polities.

Article 34 of the Covid-19 Law - https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/COVID19TMA2020.

Shin H., South Korea's COVID-19 measures land president Moon's party a massive election victory, Reuters, April 16, 2020, https://globalnews.ca/news/6825336/coronavirus-south-korea-election/.

The latest version of the national government guidance paper on pandemics issued in 2018.

Section 39 empowers the Knesset (Israeli legislature) to declare a state of emergency for one year. As long as such declaration is in force, the government is authorized to issue emergency regulations that may alter any law, or temporarily suspend its effect. Such regulations cannot violate human dignity and are subject to judicial review. In fact, Israel has been under a declaration of a state of emergency since independence in 1948, renewed by the Knesset every year.

Chief Economist of the Ministry of Finance, https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/dynamiccollectorresultitem/periodic-review-07072020/he/weekly_economic_review_periodic-review-07072020.pdf.

References

- 1.Golson G.J., Penuel B.K., Statler M., Hagen R., editors. Encyclopedia of Crisis Management. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerber B.J. Disaster management in the United States: examining key political and policy challenges. Pol. Stud. J. 2007;35:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakema M., Parra C., McCann P. Learning from the rubble: the case of Christchurch New Zealand after 2010 and 2011 earthquakes. Disasters. 2018;43:431–455. doi: 10.1111/disa.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmeli A., Schaubroeck J. Organizational crisis-preparedness: the importance of learning from failures. Long. Range Plan. 2008;41:177–196. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altshuler A. Emergency preparedness of local authorities: general model and the Israeli case. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2010;25:39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon M.J. Fighting COVID-19 with agility transperancy and participation: wicked policy problems and new governance challenges. Publ. Adm. Rev. 2020;80:651–656. doi: 10.1111/puar.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newig J., Kochskamper E., Challis E., Jager N.W. Exploring governance learning: how policymakers draw on evidence, experience, and intuition in designing participatory flood risk planning. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2016;55:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comfort L.K., Waugh W.L., Cigler B.A. Emergency management research and practice in public administration: emergence, evolution, expansion and future directions. Publ. Adm. Rev. 2012;72:539–548. [Google Scholar]

- 9.An B.Y., Tang S.-Y. Lessons from COVID-19 responses in East Asia: institutional infrastructure and enduring policy instruments. Am. Rev. Publ. Adm. 2020;50:790–800. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandstrom A., Carlsson L. The performance of policy networks: the relation between network structure and network performance. Pol. Stud. J. 2008;36:497–524. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wucker M. Macmillan; 2016. The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altshuler A. INSS Publications; Tel-Aviv: 2016. Israel's Emergency Management Challenges; pp. 147–154. Strategic Survey for Israel 2015-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez H., Quarantelli E.L., Dynes R.R., editors. Handbook of Disaster Research. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henstra D. The dynamic of policy change: a longitudinal analysis of emergency management in Ontario 1950-2010. J. Pol. Hist. 2011;23:399–428. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birkland T.A. Georgetown University Press; Washington DC: 2006. Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change after Catastrophic Events. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabatier P.A. Knowledge, policy-oriented learning, and policy change: an advocacy coalition framework. Knowledge. 1987;8(4):649–692. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlop C.A., Radaelli C.M. Systematizing policy learning: from monolith to dimensions. Polit. Stud. 2013;61:599–619. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paasi M. Collective benchmarking of policies: an instrument for policy learning in adaptive research and innovation policy. Sci. Publ. Pol. 2005;32(1):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.George B., Verschuere B., Wayenberg E., Zaki B.L. A guide to benchmarking COVID‐19 performance data. Publ. Adm. Rev. 2020;80(4):696–700. doi: 10.1111/puar.13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitsma M.B., Goldhaber-Fiebert J.D., Salomon J.A. Quantifying and benchmarking disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates by race and ethnicity. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30343. e2130343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asahi K., Undurraga E.A., Wagner R. Benchmarking the CoVID-19 pandemic across countries and states in the USA under heterogeneous testing. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94663-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goyal N., Howlett M. Measuring the Mix” of policy responses to COVID-19: comparative policy analysis using topic modelling. J. Comp. Pol. Anal.: Research and Practice. 2021;23(2):250–261. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mei C. Policy style, consistency and the effectiveness of the policy mix in China's fight against COVID-19. Policy and Society. 2020;39(3):309–325. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2020.1787627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapat A., Li Y., Mitchell C., Esnard A.-M. Policy learning and policy change: katrine, Ike and post-disaster housing. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters. 2011;29:26–56. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkland T.A. Disasters, lessons learned and fantasy documents. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2009;17:146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowell B., Steelman T., Velez A.-L.K., Yang Z. The structure of effective governance of disaster response networks: insights from the field. Am. Rev. Publ. Adm. 2018;48:699–715. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau J.T.F., Yang X., Tsui H., Kim J.H. Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong-Kong: from day 10 to day 62. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2003;57(11):864–870. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sze Y.H., Ting W.F. When civil society meets emerging systemic risks: the case of Hong-Kong amidst SARS. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development. 2004;14(1):33–50. http://hdl.handle.net/10397/8528 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee K.-M., Jung K. Factors influencing the response to infectious diseases: focusing on the case of SARS and MERS in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16:1432. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim S.H., Sziarto K. When illiberal and the neoliberal meets around infectious diseases: an examination of the MERS response in South Korea. Territory, Politics, Governance. 2020;8:60–76. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deurenberg-Yap M., Foo L., Low Y., Chan S., Vijaya K., Lee M. The Singaporean response to the SARS outbreak: knowledge sufficiency versus public trust. Health Promot. Int. 2005;20:320–326. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shwartz J., Yen M.-Y. Toward a collaborative model of pandemic preparedness and response: taiwan's changing approach to pandemics. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017;50(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan Y., Chen M. In: SARS pp.147-164. Davis D., Siu H.F., editors. Taylor and Francis; New-York: 2007. The weakness of the post-authoritarian democratic society. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chua B.H. Sars epidemic and the disclosure of Singapore nation. Cult. Polit. 2006;2(1):77–96. doi: 10.2752/174321906778054664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh J., Lee J.-K., Schwarz D., Ratcliffe H., Markuns J., Hirschhorn L. National response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Systems & Reform. 2020;6(1) doi: 10.1080/23288604.2020.1753464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C.-L. Taiwan's proactive prevention of COVID-19 under constitutionalism. 2020. https://verfassungsblog.de/taiwans-proactive-prevention-of-covid-19-under-constitutionalism

- 37.Lee T.-L. Legal preparedness as part of COVID-19 response: the first 100 days in Taiwan. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002608. published online May 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeung G. Fear of unaccountability vs. fear of a pandemic: Covid 19 in Hong-Kong. 2020. https://verfassungsblog.de/fear-of-unaccountability-vs-fear-of-a-pandemic-covid-19-in-hong-kong/

- 39.Wan K., Ho L., Wong N., Chiu A. vol. 134. World Development; 2020. pp. 1–7. (Fighting COVID-19 in Hong-Kong: the Effects of Community and Social Mobilization). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim H. The sociopolitical context of the COVID-19 response in South Korea. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woo J.J. vol. 39. Policy and Society; 2020. pp. 345–362. (Policy Capacity and Singapore's Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S., Palayew A., Billari F.C., Binagwaho A., Kimball S.…El-Mohandes A. COVID-SCORE: a global survey to assess public perceptions of government responses to COVID-19 (COVID-SCORE-10) PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong C.M.L., Jensen O. The paradox of trust: perceived risk and public compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. J. Risk Res. 2020;23:1021–1030. [Google Scholar]

- 44.You J. Lessons from South Korea's Covid-19 policy response. Am. Rev. Publ. Adm. 2020;50(6–7):801–808. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwok K.O., Li K.K., Chan H.H., Yi Y.Y., Tang A., Wei W.I., Wong Y.S. MedRxiv; 2020. Community Responses during the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Hong-Kong: Risk Perception, Information Exposure and Preventive Measures. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartley K., Jarvis D.S. Policymaking in a low-trust state: legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy and Society. 2020;39:1–21. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.OECD Evaluating the initial impact of COVID-19 containment measures on economic activity. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/evaluating-the-initial-impact-of-covid-19-containment-measures-on-economic-activity-b1f6b68b/

- 48.Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Isofidis C., Agha M., Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a Review. Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang C.J., Ng C.Y., Brook R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technologies and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peleg K., Bodas M., Hertelendy A.J., Kirsch T.D. The COVID-19 pandemic challenge to the All-Hazards Approach for disaster planning. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021;55:102103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shmueli D.F., Segal E., Ben-Gal M., Feitelson E., Reichman A. Earthquake readiness in volatile regions: the case of Israel. Nat. Hazards. 2019;98(2):405–423. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elran M., Shaham Y., Altshuler A. Tel-Aviv: INSS Publications; 2016. An Expanded Comprehensive Threat Scenario for the Home Front in Israel. INSS Insight, 828. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maor M., Sulitzeanu-Kenan R., Chinitz D. When COVID-19 constitutional crisis and political deadlock meet: the Israeli case from a disproportionate policy perspective. Policy and Society. 2020;39:442–457. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2020.1783792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sang-Hun C., Krolik A., Zhong R., Singer N. New York Times; 2020. Major Security Flaws Found in South Korea Quarantine App.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/21/technology/korea-coronavirus-app-security.html July 21. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barron L. TIME; 2020. This Shouldn't Be about Politics: Hong Kong Medical Workers Call for Border Shutdown amid Coronavirus Outbreak.https://time.com/5777285/hong-kong-coronavirus-border-closure-strike February 4. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanna D., Huang Y. The impact of SARS on Asian economies. Asian Econ. Pap. 2004;3(1):102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horton R. Academic webinar for the University of Haifa faculty members; 2020. What Can We Learn from the Corona Crisis? 9.11.2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tufekci Z. The Atlantic; 2020. How Hong-Kong Did it: with the Government Flailing, the City's Citizens Decided to Organize Their Own Coronavirus Response. May 12. [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Bank . Global Economic Prospects. 2020. Global outlook: pandemic recession: the global economy in crisis.https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects downloaded from: [Google Scholar]

- 60.OECD and NEA No. 7308 . 2018. Towards an All-Hazards Approach to Emergency Preparedness and Response.https://www.oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-12/7308-all-hazards-epr.pdf NEA No. 7308. [Google Scholar]