Graphical abstract

SNF-Cu2-xS have been prepared through one-step hydrothermal method, where the Cu2-xS crystals are in-situ grown on the surface of SNF with the help of commercial textile adhesion promoter. The SNF-Cu2-xS exhibited excellent antibacterial and antiviral ability under the IR illumination.

Keywords: Infrared baking lamp, Facemasks, Photothermal effect, Antibacterial, Antiviral

Abstract

Disposable surgical masks are widely used by the general public since the onset of the coronavirus outbreak in 2019. However, current surgical masks cannot self-sterilize for reuse or recycling for other purposes, resulting in high economic and environmental costs. To solve these issue, herein we report a novel low-cost surgical mask decorated with copper sulfide (Cu2-xS) nanocrystals for photothermal sterilization in a short time (6 min). With the spun-bonded nonwoven fabrics (SNF) layer from surgical masks as the substrate, Cu2-xS nanocrystals are in-situ grown on their surface with the help of a commercial textile adhesion promoter. The SNF-Cu2-xS layer possesses good hydrophobicity and strong near infrared absorption. Under the irradiation with an infrared baking lamp (IR lamp, 50 mW cm−2), the surface temperature of SNF-Cu2-xS layer on masks can quickly increase to over 78 °C, resulting from the high photothermal effects of Cu2-xS nanocrystals. As a result, the polluted masks exhibit an outstanding antibacterial rate of 99.9999% and 85.4% for the Escherichia coli (E.coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) as well as the inactivation of human coronavirus OC43 (3.18-log10 decay) and influenza A virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (3.93-log10 decay) after 6 min irradiation, and achieve rapid sterilization for reuse and recycling. Therefore, such Cu2-xS-modified masks with IR lamp-driven antibacterial and antiviral activity have great potential for real-time personal protection.

1. Introduction

Infectious diseases, caused by various kinds of pathogenic bacteria and viruses, pose long-lasting severe threats to both personal health and public safety [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. These common pathogenic bacteria include Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Tubercle bacillus and Escherichia coli (E. coli), which possess strong environmental adaptability and high reproduction speed. Only a tiny amount of them are capable of rapid amplification in drinking water, food or medical equipment, thus causing diseases such as skin pustule, respiratory infections, or urinary inflammation. Compared to bacteria, the infectious viruses tend to have high transmission rates and are responsible for tens of millions of casualties each year, e.g., the notorious “Spanish flu” with tens of millions of casualties in the early twentieth century, and the “swine flu” in 2009 that costs 18,500 lives [6]. In order to combat these pathogenic bacteria and viruses, researchers around the world have devoted their passion to developing several novel drugs for treating bacterial infection (such as antibiotics [7], antimicrobial peptides [8], [9] and bacteriophage [10]) and viruses infection including adamantan(amin)e derivatives (amantadine) [11], neuraminidase inhibitors (zanamivir and oseltamivir) [12], ribavirin [13], and interferon [14], etc. These drugs exhibit positive effects for fighting infections by inhibiting the replication cycle or blocking the release of the newly formed virus, whereas their development takes a long time and cost and drug resistance may arise gradually. In addition, researchers have also developed light-induced antimicrobial therapies, photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT), which have the advantages of no drug resistance, low cytotoxicity, and low side effects [15], [16], [17]. These treatments can provide safe and effective antimicrobial activity by utilizing visible and near-infrared light [18], [19].

Currently, the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic initiated by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused a myriad of infection cases and deaths across the globe (262 and 5.22 million, by November 30, 2021) [20], [21]. There are lots of drugs under investigation and some of them have proved to be effective in inhibiting infection of SARS-CoV-2, such as paxlovid and molnupiravir [22], [23], [24]. As the first line of defense against infection, the self-protection measures are still of great importance including hand-washing, social isolation, and facemask-wearing. Both airborne transmission through inhalation of aerosols containing virus (the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19) and contact transmission through viral shedding of droplets can be blocked by face-covering [25]. However, the standard surgical masks are only forms of obstructions that can prevent passively bacteria and viruses from contacting people, instead killing pathogens. Aerosols containing bacteria and viruses on the surface of masks even can cause serious infections to wearers or medical waste handlers. It has been reported that the global production rates of surgical masks are 40 million per day during the pandemic of COVID-19 in 2019–2020, resulting in more than 15,000 tons of waste per day [26]. To dispose of these huge amounts of used masks, most countries tend to incinerate them, which releases toxic gases that pollute the environment [27]. Therefore, it is necessary to kill bacteria and viruses on masks for re-use and/or public health safety.

For the decontamination and reuse of masks, ultraviolet (UV) germicidal irradiation, vaporous hydrogen peroxide, and moist heat are the three main methods for sterilizing masks [28]. For example, UV treatment offers a chemical-free strategy and disrupts DNA and RNA, thus inactivating viruses and other microorganisms [29]. In addition, several sterilization strategies from the synthesis of masks have been proposed to improve the antibacterial/antiviral properties and reusability of facemasks. The first strategy is to impregnate inorganic nanomaterials into facemasks. Early 2010, Borkow et al. prepared the modified N95 respiratory masks impregnated with 2.2 wt.% copper oxide with anti-microbial properties, which safely reduced the risk of influenza virus environmental contamination without altering the filtration capacities of masks [30]. However, the modified N95 respiratory masks have a weak antiviral efficiency. The second strategy is to load organic photosensitizers on cotton fibers to achieve the solar-induced generation of cytotoxic radical oxygen species [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. For example, the surgery facemasks were firstly surface-modified with 2-diethylaminoethyl chloride polycationic short chains and then reacted with Rose Bengal and anthraquinone-2-sulfonic acid sodium salt monohydrate photosensitizers, which produced radical oxygen species to against bacteria (e.g., E. coli and grampositive Listeria innocua) under the sunlight illumination [32]. However, the modified surgery facemasks take a long time (60 min) to achieve 99.9999% reductions against bacteria and bacteriophage. The third strategy is to develop carbon-modified facemasks with the solar light heating [26], [37]. Li et al. prepared the few-layer graphene-functionalized facemasks through a dual-mode laser-induced forward transfer method, and the facemasks exhibited rapid temperature elevation under sunlight illumination, thus making the masks reusable after sunlight sterilization [26]. Therefore, it is also feasible to develop NIR-responsive photothermal agents with antibacterial and antiviral activity.

Copper sulfide, with a unique semiconducting and low-toxic nature, has been widely used in various applications, such as photocatalysis [38], in vitro biosensing [39], wound healing [40] and tumor therapy [41]. Copper sulfide possesses strong localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs) effect due to the existence of a large number of copper vacancies. Thus, it has strong near-infrared (NIR) absorption characteristics, resulting in a high-efficiency photothermal conversion. In addition, infrared (IR) radiation is electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths (0.76–5 μm) longer than those of visible light, and it has sufficient energy to excite molecules to result in enhanced vibrations. The heat-source equipment with strong IR radiation can be easily found in our daily life, for instance, the bathroom heater with warming capacity. Inspired by these characteristics, in this work, we applied IR lamp (wavelength: 0.76–5 μm, 100 W) as the irradiation source and developed spun-bonded nonwoven fabrics (SNF) coupled with Cu2-xS nanoparticles (SNF-Cu2-xS) for rapid and efficient destruction of bacteria and viruses. The SNF-Cu2-xS were prepared by the in-situ growth of Cu2-xS nanoparticles on SNF layer with the help of a commercial textile adhesion promoter. Under illumination with IR lamp, the SNF-Cu2-xS exhibit fast elevation of local temperature over 78 ℃, which lead to high killing efficiency and cycling stability for bacteria (E. coli and S. aureus) and viruses (HCoV-OC43 and PR8) within a few minutes of IR exposure. Apart from fast heating sterilization with the IR lamp, SNF-Cu2-xS possessed good antibacterial and antiviral effects due to the presence of Cu2-xS nanomaterials with Cu ions. Therefore, the combination of SNF-Cu2-xS and IR lamp shows a promise strategy with efficient antibacterial and antiviral capacity.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Surgical masks were purchased from Nanchang Zhenfeng Sanitary Materials Co., Ltd. Copper (II) chloride dihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O), trisodium citrate, polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP, K30), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), and sodium sulfide (Na2S·9H2O) were brought from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology. The adhesion promoter (CS-555) containing the amino-contained silane coupling agent was purchased from Nanjing Chuangshi Chemical Additives Co., Ltd. All the chemicals were used as received without further purifications. Infrared lamp (Philips, T04-R95E100W) was purchased from Shanghai Yafu Lighting Appliance Co., Ltd.

2.2. Preparation of SNF-Cu2-xS

Surgical facemasks consist of three layers, where outer-layer is hydrophobic spun-bonded nonwoven fabrics (SNF), the middle-layer is melt-blown nonwoven fabrics (MNF), and the inner layer is hygroscopic spun-bonded nonwoven fabrics. SNF layers was activated in H2SO4 solution (98%) at room temperature for 1 day to produce the sulfonic acid groups (-SO3H) for improving the conjugation effect with Cu2+ ions and the adhesion promoter, and then washed with deionized water and dried. The activated SNF were then dispersed in the adhesion promoter containing the amino-contained silane coupling agent for further use. To prepare SNF-Cu2-xS, 0.6 g PVP and 0.43 g CuCl2·2H2O were firstly dissolved in 30 mL deionized water to form a light blue solution under vigorous stirring, followed by the dropwise addition of trisodium citrate aqueous solution (40 mg mL−1, 10 mL). Trisodium citrate can chelate with Cu ions to prevent aggregation and size overgrowth of Cu2-xS nanoparticles. Then, the SNF were immersed in the above solution and left to soak for 30 min, and Na2S solution (744 mg mL−1, 50 μL) was then added. The mixture was heated at 90 °C for 15 min under magnetic stirring for the in-situ growth of Cu2-xS nanocrystals. Finally, Cu2-xS coated SNF (SNF-Cu2-xS) were rinsed with deionized water three times and oven-dried at 60 °C.

2.3. Characterization

The samples were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Talos F200S), field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, S-4800), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Escalab 250Xi), powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D4), and UV–vis-NIR absorption spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-3600). The IR baking lamp was used to investigate the photothermal effects of SNF-Cu2-xS. A thermal camera (FLIR A300, FLIR Systems) was used to record the temperature. The water contact angle was measured by Contact Angle Meter (OSA200). The air permeability of the sample was measured by air permeability tester (YG461E).

2.4. Photothermal tests

The photothermal effect of SNF-Cu2-xS was studied by using the IR baking lamp as the irradiation source. Typically, SNF-Cu2-xS (length: 2 cm, width: 2 cm) were irradiated by the baking lamp with different power intensities (50, 100, 200 mW cm−2), and their temperature was real-time recorded by using an infrared thermal imaging camera.

2.5. Antibacterial tests

Escherichia coli (E. coli, American Type Culture Collection 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, American Type Culture Collection 25923) were chosen for evaluating the antibacterial ability of SNF-Cu2-xS. The antibacterial activity of SNF-Cu2-xS was determined by the plate counting method and the morphological changes of bacteria were observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). Briefly, the SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS (length: 1 cm, width: 1 cm) were sterilized by ultraviolet light before testing. Then, they were immersed in 2 mL of diluted bacteria suspension at a concentration of 2 × 106 CFU mL−1 and coincubated for 30 min in a shaking incubator. Afterward, the SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were irradiated by the IR lamp (50, 100, 200 mW cm−2) for 0 ∼ 6 min. The bacterial suspensions incubated in PBS with and without irradiation served as the blank samples. The SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were added into 10 mL PBS (pH = 7.4) to obtain the bacterial suspension under vigorous oscillation and the obtained suspension samples were diluted 100 times. 100 µL of the diluted bacterial solutions were spread evenly onto fresh Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates in triplicates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial colonies were photographed and calculated. And the antibacterial efficiency was calculated using the Eq. (1) [42]:

| (1) |

where Nt represented the number of colonies in the treatment groups, and Nc represented the number of colonies in the blank group. The morphology observation of the bacteria after the antibacterial assay was visualized by SEM imaging. Typically, the SNF-Cu2-xS/bacteria conjugate samples were washed with PBS and fixed overnight with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. After that, these samples were dehydrated by sequential treatment of ethanol solutions (20 ∼ 100%) for 10 min, respectively, and dried naturally.

2.6. Antiviral tests

The antiviral function was examined against two model viruses: human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43, American Type Culture Collection VR-1558) and influenza A virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (PR8, American Type Culture Collection VR-95). SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were cut into pieces at 1 cm × 1 cm. Then, 50 μL of virus suspension (1 × 106 PFU mL−1, HCoV-OC43 and PR8) was added to the specimen. After full infiltration with the virus, the SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were irradiated by the IR lamp to evaluate the antiviral effect of different intensities and irradiation time. Then, the virus was recovered from the SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS with 5 mL dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) by vortex at the indicated irradiated time, and the amount of the virus in the eluant was determined by plaque assay after aseptic filtration with 0.22 μm filter and serial dilutions. For the plaque assay, cells were seeded onto six-well cell culture plates and incubated overnight to form a confluent monolayer. The serial-diluted eluant containing the virus was added into the wells and then incubated for 2 h at 34 °C in 5% CO2. After removing the eluant and adding an overlay medium, the plates were further incubated for several days at 34 °C in 5% CO2 until the plaque developed. After being fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 1% crystal violet, the plaques were visualized, and the plaque-forming units (PFU) were counted. And the antiviral efficiency was calculated using the Eq. (2) [43]:

| (2) |

where Nt represented the titer of the virus suspension in the IR-treated groups, and N0 represented the titer of the virus suspension in the control group.

2.7. Air permeability and aerosol filtration performance tests

SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were cut into pieces at 8 cm × 8 cm. The air permeabilities of SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were measured under 100 Pa by an air permeability tester. The test standard was GB_T5453:1997, and the test area was 20 cm2. Aerosol filtration performance of disposable surgical mask and Cu2-xS-modified mask were measured by an automatic filter tester (TSI 8130). The tester produced charge neutralized monodisperse NaCl aerosol particles with a median mass diameter of 260 nm, a median diameter of 75 nm and a geometric standard deviation of < 1.86. The airflow passed through a sample with an effective test area of 100 cm2 at a speed of 5.3 cm S-1 (volume flow rate: 32 L min−1). Each sample was measured at least 3 times.

2.8. Cytotoxicity tests

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) were cultured with SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) for 24 h and 48 h. The medium was then removed and 100 μL MTT solution (5 mg mL−1) was added. After 4 h, the MTT was discarded, 150 µL dimethyl sulfoxide was added and the solution shaken for 15 min. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 490 nm with a microplate reader.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of SNF-Cu2-xS

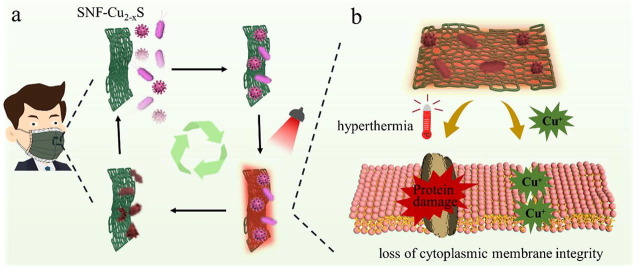

In this work, Cu2-xS nanoparticles (with photothermal effect) were in-situ grown on SNF to obtain SNF-Cu2-xS, which were used to assemble with other layers to construct reusable masks. If users wear the Cu2-xS -modified mask in an environment with viruses and bacteria, the viruses and bacteria will be adsorbed and accumulate on the surface (SNF-Cu2-xS) of a mask (Fig. 1 a). Then, under IR lamp irradiation, the SNF-Cu2-xS could rapidly and efficiently destroy bacteria and viruses through a combination of heat-induced effect and Cu ions. The modified mask can be reused after disinfection, limiting the environmental hazards caused by disposable masks. The inactivation of bacteria and viruses by SNF-Cu2-xS should be attributed mainly to Cu2-xS nanocrystals (Fig. 1b). On the one side, SNF-Cu2-xS generate hyperthermia under IR lamp irradiation, which can thermally destroy bacteria and viruses. For bacteria, hyperthermia can cause the crinkle and rupture of cell membrane of bacterium, which can lead to the content leaking. For viruses, the surface spikes and lipid membrane of virions are damaged. On the other hand, the copper ions of Cu2-xS are detrimental to proteins and genomes of bacteria and viruses, including the disintegration of envelope and dispersal of surface spikes. It has also been demonstrated that copper toxicity for bacteria involves the direct or indirect action [44]. Taken together, we can conclude that SNF-Cu2-xS have excellent and unique antibacterial and antiviral activity.

Fig. 1.

a) A scheme showing the surgical facemasks with surface aerosols/droplets containing bacteria and viruses. The SNF-Cu2-xS with bactericidal and antiviral capacity under IR lamp. b) Illustration of the antibacterial and antiviral mechanism of SNF-Cu2-xS through hyperthermia and Cu+ ions.

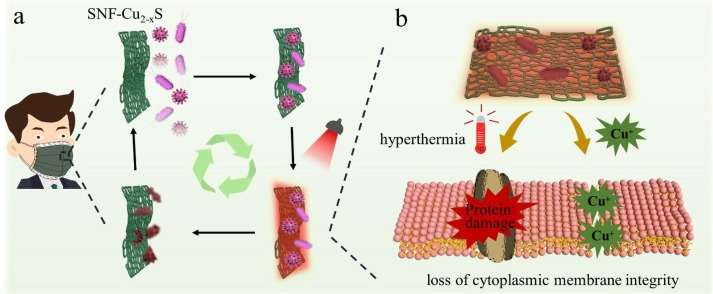

In-situ growth of Cu2-xS on SNF was realized by the one-step coprecipitation method, where a commercial textile adhesion promoter acted as an adhesive agent (Fig. 2 a). Before the Cu2-xS growth, the bare SNF are composed of fibers and cross-linked platforms with a three-dimensional network, which leads to high air permeability (Fig. 2b, c). The fibers of bare SNF have a smooth surface, and they exhibit an average size of 40 μm (Fig. 2d). After the Cu2-xS growth, SNF-Cu2-xS show dark-green color but maintain a three-dimensional network similar to bare SNF (Fig. 2e, f). Importantly, the fibers of SNF-Cu2-xS possess a coarse surface, suggesting the presence of Cu2-xS coating and adhesion polymer (Fig. 2g).

Fig. 2.

a) Schematic illustration of the preparation process of SNF-Cu2-xS. b-d) SEM images of SNF. e-g) SEM images of SNF-Cu2-xS.

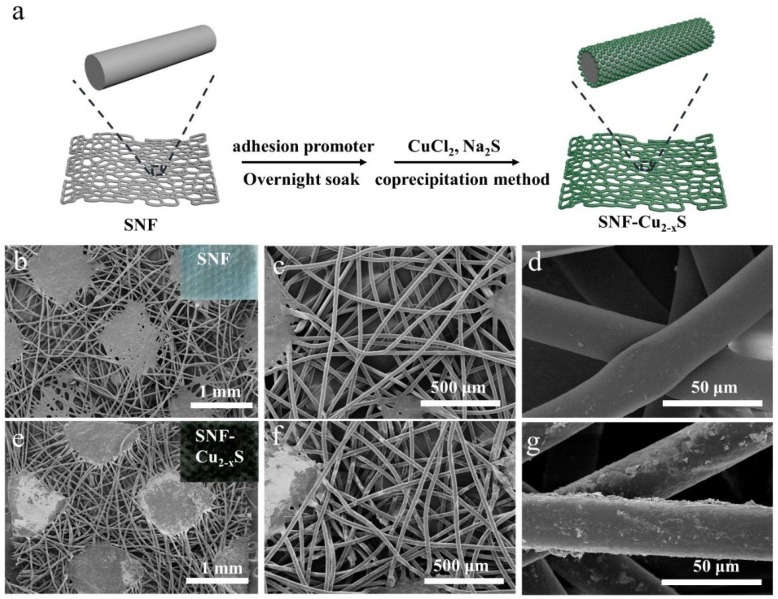

The composition and microstructure of SNF-Cu2-xS were further investigated by EDS elemental mapping, TEM, XRD, and XPS. The elemental mapping images of SNF-Cu2-xS demonstrate strong signals of C, Si, O, S, and Cu, in which C signal stems from the fibers, Si/O signal come from adhesion polymer, and S/Cu signals are derived from Cu2-xS nanocrystals (Fig. 3 a). Cu2-xS nanocrystals obtained by ultrasound from the SNF-Cu2-xS were also analyzed. TEM images demonstrate that the Cu2-xS nanocrystals have an average size of ∼ 12 nm, and they have an interplanar spacing of ∼ 0.32 nm which corresponds with the (1 0 1) plane of Cu2-xS (JCPDS card no. 06–0464) [45] (Fig. 3b, Fig. S1a). In addition, XRD pattern (Fig. 3c) shows some main diffraction peaks at 29.13°, 31.81°, and 47.85°, corresponding to (1 0 2), (1 0 3), and (1 1 0) planes of hexagonal phase covellite Cu2-xS (JCPDS card no. 06–0464). The well-defined peaks in XRD pattern indicate the formation of hexagonal phase Cu2-xS with high crystallinity. The survey XPS spectrum (Fig. S1b) of Cu2-xS nanocrystals confirms the presence of Cu and S elements. Cu 2p spectrum (Fig. 3d) exhibits two binding energies at 932.3 eV and 952.1 eV, which are associated with Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2 from Cu(I) state, confirming the presence of only Cu(I) state in Cu2-xS nanocrystals [45], [46], [47]. Previous study has shown that copper ionic species are essential in inactivating viruses and particularly Cu(I) is more significant in the longer term [48]. Therefore, these results confirm the successful surface modification of Cu2-xS on SNF.

Fig. 3.

a) EDS elemental mapping of SNF-Cu2-xS. b) TEM and HRTEM images of Cu2-xS nanocrystals obtained from the SNF-Cu2-xS. c) XRD pattern of Cu2-xS nanocrystals. d) Cu 2p spectrum.

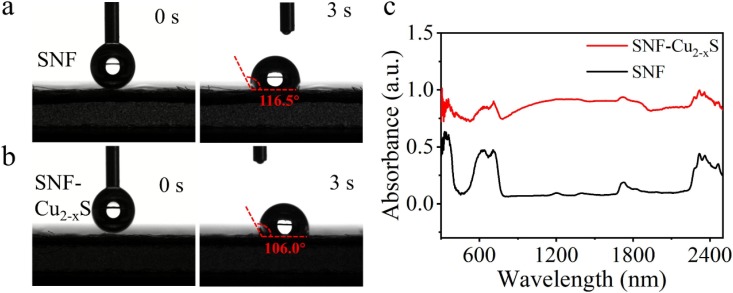

Subsequently, the hydrophobicity, optical property and air permeability of SNF-Cu2-xS were investigated. To examine hydrophobicity, the contact angles of SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were studied. When the water droplet (2 μL) is placed on the SNF, the contact angle remains at 116.5° (Fig. 4 a). For SNF-Cu2-xS, the contact angle is determined to be 106.0° (Fig. 4b), which is very close to SNF. These results show that SNF-Cu2-xS maintain the hydrophobicity of SNF, which can prevent the attachment of water droplets carrying viruses and bacteria. Moreover, the optical diffusion spectra of SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were analyzed. Compared to the low absorbance intensity of SNF, SNF-Cu2-xS exhibit enhanced absorbance from 400 to 2500 nm (Fig. 4c), which results from the surface plasmon resonance absorption and diffuse reflection absorption of Cu2-xS. Compared with SNF with an absorption efficiency of 20.6%, SNF-Cu2-xS shows an absorption with absorption efficiency of 82.4%, which is close to the absorption of graphene [26]. At the same time, the air permeabilities of SNF-Cu2-xS were measured under 100 Pa. The air permeabilities of SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were determined to be 1936.89 and 1880.57 mm s−1, respectively, implying that the permeability is barely affected by the Cu2-xS coating (Fig. S2). Besides, the mass of SNF-Cu2-xS was measured under strong airflow (Fig. S3). After 120 min of strong airflow, the quality of SNF-Cu2-xS remains stable with almost no loss, which confirms the strong adhesion of Cu2-xS on SNF. These facts indicate excellent hydrophobicity, air permeability, adhesion stability, and strong photoabsorption of SNF-Cu2-xS.

Fig. 4.

Photographs of a water droplet on the surface of a) the pristine SNF and b) SNF-Cu2-xS at 0 and 3 s. c) Absorption spectra of SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS.

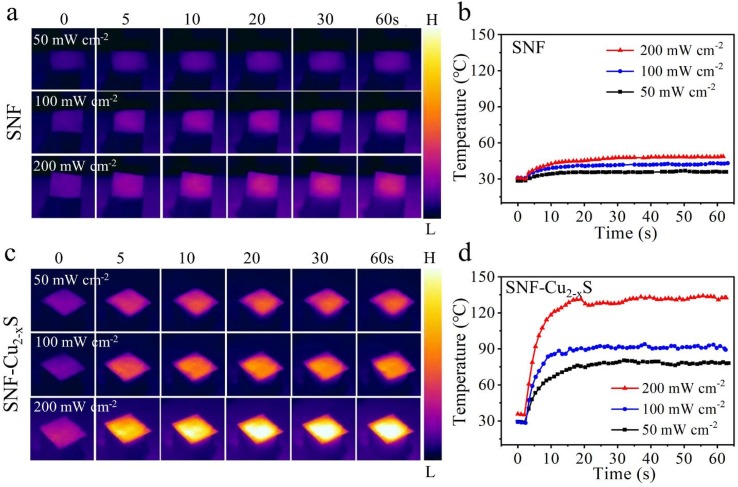

The photothermal performances of SNF-Cu2-xS were studied by using an IR lamp at different power densities. For comparison, the photothermal effects of SNF were also tested. The temperature elevation of SNF rises from ∼ 30 to 35.2, 42.7, 48.9 °C after 60 s with the increase of power density from 50 to 100, 200 mW cm−2, respectively (Fig. 5 a, b). The SNF show a low temperature elevation as shown in the IR image. Of note, the temperature below 50 °C is not enough to kill bacteria (E. coli). Importantly, the temperature of SNF-Cu2-xS shows an obvious change, reaching the maximum local temperature of 79.5, 90.2, 130.9 °C at the power density of 50, 100, and 200 mW cm−2 (Fig. 5c, d), respectively. The rapid temperature increase reflects the excellent photothermal properties of Cu2-xS, which is conducive to rapid sterilization. These facts indicate that the SNF-Cu2-xS can be used as an effective photothermal facemask.

Fig. 5.

Thermographic images of a) SNF and c) SNF-Cu2-xS. The corresponding temperature elevation curves of b) SNF and d) SNF-Cu2-xS under different power densities.

3.2. Antibacterial functions of SNF-Cu2-xS

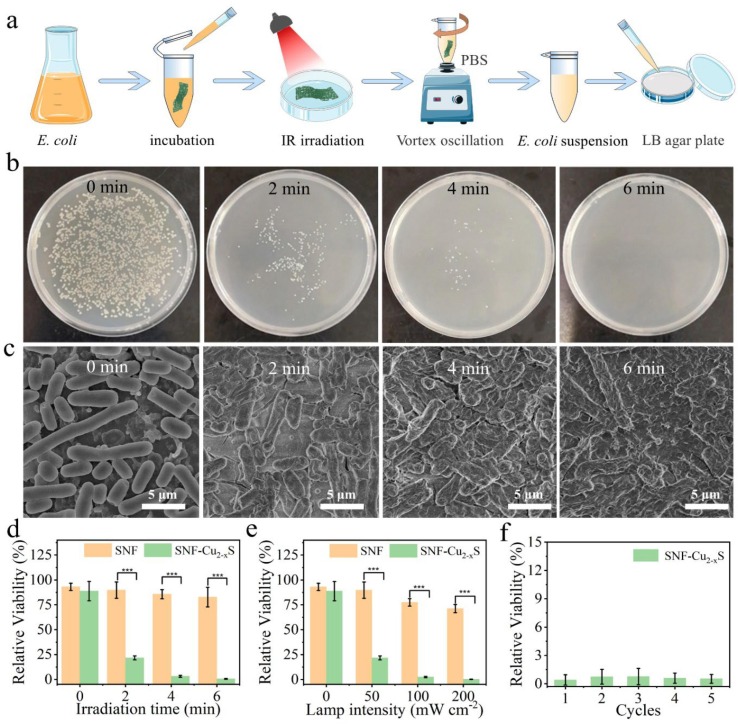

Based on the excellent photothermal conversion, the antibacterial activities of SNF-Cu2-xS against E. coli were explored by the plate counting method and SEM morphology observation. The schematic diagram of photothermal sterilization is shown in Fig. 6 a. The effect of exposure time on the bactericidal rate of SNF-Cu2-xS was firstly studied. In the control group (without treatment), a large number of viable colonies appear on the LB agar plate after culturing in a 37 °C incubator for 24 h, and they have intact cell morphologies and smooth surfaces (Fig. 6b, c). On the contrary, once exposed to lamp illumination at 50 mW cm−2 for 2 and 4 min, most of the bacteria were killed and show wrinkled or even ruptured bacterial cell membranes. With the prolonged exposure time to 6 min, the number of colonies decreased to nearly zero, and no normal morphology of E. coli could be found, indicating the strongest killing efficiency. The survival rate of E. coli was summarized in Fig. 6d. There is no obvious change in survival rate for E. coli treated SNF at 50 mW cm−2 within 6 min of illumination due to the absence of antibacterial functions. In contrast, the bacterial killing ratios of E. coli treated SNF-Cu2-xS at 50 mW cm−2 increased significantly (***p < 0.001) in comparison to that for SNF group, and they are determined to be 78.3%, 96.9%, and 99.9999% after the irradiation for 2, 4, and 6 min, respectively. Subsequently, the effect of power density on the antibacterial rate of SNF-Cu2-xS was then examined. After the treatment with the lamp at different intensities (50, 100, and 200 mW cm−2) for 2 min, E. coli exhibited a significant decrease in the number of colonies in comparison to the control group (Fig. S4). Specifically, the antibacterial efficiency for 50, 100, and 200 mW cm−2 are determined to be 78.3%, 97.6%, and 99.9999%, respectively (Fig. 6e), showing similar antibacterial activity to the laser-induced graphene (LIG) material [49]. Meanwhile, the antibacterial ratios of E. coli treated with SNF remain low under the other identical conditions. Thus, the combination of SNF-Cu2-xS and IR lamp illumination can efficiently and rapidly destroy E. coli.

Fig. 6.

a) Schematic diagram of photothermal sterilization. b) Photographs of the E. coli colonies on LB agar solid plates after the treatments with SNF-Cu2-xS and IR lamp (50 mW cm−2, 0–6 min). c) SEM images of E. coli. d) The survival rate of E. coli treated with SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS at 50 mW cm−2 for different durations (***p < 0.001 (highly significant)). e) The survival rate of E. coli treated with SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS at 50–200 mW cm−2 for 2 min (***p < 0.001). f) The repeated antibacterial rate of SNF-Cu2-xS.

To test the sterilization cyclic stability of SNF-Cu2-xS, we repeated the sterilization process 5 times at 100 mW cm−2 for 2 min irradiation. During the sterilization cycles, the antibacterial rates of SNF-Cu2-xS show a minor change and almost all E. coli were destroyed, showing high stability of sterilization (Fig. 6f). Thus, the SNF-Cu2-xS can be reused at least five times. In addition, the washing stability of SNF-Cu2-xS was also investigated to determine the stability of Cu2-xS. The SNF-Cu2-xS was washed in detergent water at 300 rpm for 20 min. After washing cycles, the antibacterial performance was measured by the spread plate method at 200 mW cm−2 for 2 min irradiation. The antibacterial efficacy of SNF-Cu2-xS reached up to 99.92%, 98.78%, and 92.50% after one, three, five washing cycles, respectively (Fig. S5a, c). And the antibacterial rate of SNF-Cu2-xS was 99.82%, 99.53%, 99.28%, and 99.18% after washing for 10, 30, 60, and 240 min, respectively (Fig. S5b, d). The antibacterial performance of SNF-Cu2-xS remains above 90% with different washing times and cycles, demonstrating the excellent washing stability of SNF-Cu2-xS, which is close to the antibacterial performance in literature [50].

The antibacterial performance of SNF-Cu2-xS against S. aureus was investigated by the plate counting method. As shown in Fig. S6a,b, the count of S. aureus decreased slowly for SNF-Cu2-xS at 50 mW cm−2 for 2–6 min irradiation. SNF-Cu2-xS exhibited weak antibacterial activity with the rate of 43.55% for 6 min irradiation. Under 200 mW cm−2 irradiation for 2 min, 85.48% of antibacterial efficiency was achieved for SNF-Cu2-xS, far higher than other groups, demonstrating the good antibacterial performance of SNF-Cu2-xS under IR lamp treatment (Fig. S6c). The excellent bactericidal effect against E. coli and S. aureus should be attributed to the superior photothermal properties of surface Cu2-xS nanocrystals, which can quickly convert IR energy into heat, leading to the thermal ablation of bacteria. In addition, it has been reported that copper ions, like silver ions and zinc ions [51], have a antibacterial effect. The copper ions can not only interact with the bacterial membrane to disintegrate cell wall or oxidate protein [52], but also participate in cross-linking within nucleic acid strands to inhibit replication [53]. As shown in Fig. S7a,b, when bacteria (E.coli and S. aureus) interact with SNF-Cu2-xS, their viabilities go down successively with the increase of incubation time, whereas SNF has no obvious inhibition effect. Furthermore, after the repeated antimicrobial testing, we investigated the stability of SNF-Cu2-xS by SEM (Fig. S8). The morphology of SNF-Cu2-xS is the same as those before the antibacterial experiment, indicating that the SNF-Cu2-xS can be recycled for multiple uses. Therefore, the SNF-Cu2-xS exhibit stable and rapid sterilization within several minutes upon IR lamp irradiation as well as the unique antibacterial effect.

3.3. Antiviral functions of SNF-Cu2-xS

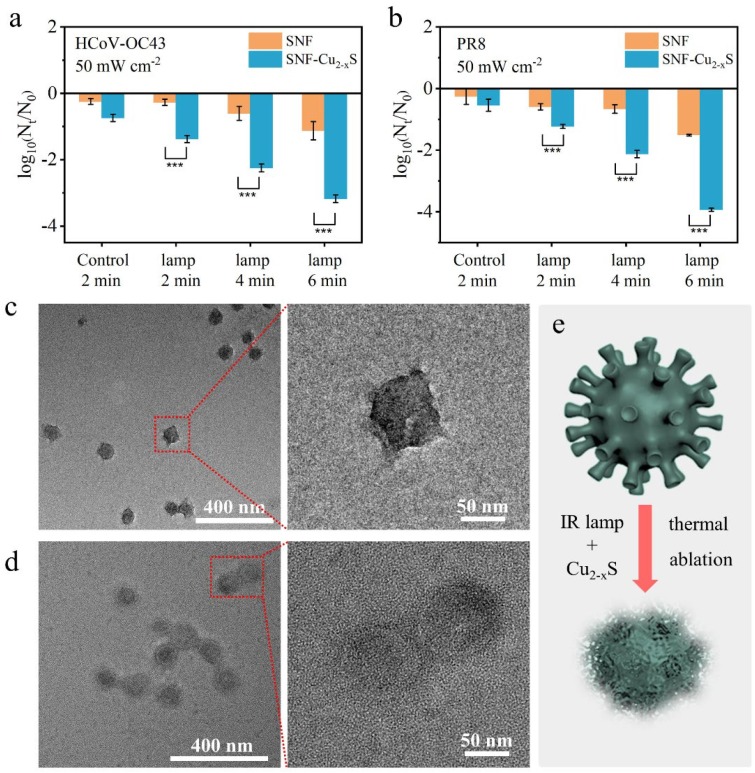

Two viruses (HCoV-OC43 and PR8) were used to evaluate the antiviral performance of SNF-Cu2-xS. The viral fluid was first separately incubated with SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS with or without IR lamp irradiation at different power intensities (50–200 mW cm−2) and exposure time (0–6 min). Then, the viruses were recovered from SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS by vortex, and the amount of virus in the eluant was determined by plaque assay. In the absence of IR lamp irradiation, the HCoV-OC43 treated by SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS are just inactivated by 0.25 and 0.74-log10, respectively (Fig. 7 a). The inactivation in SNF-Cu2-xS is faster significantly (***p < 0.001) in comparison to that for SNF group, and the inactivation rate is respectively determined to be 0.27 and 1.38-log10 by SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS after the exposure of IR lamp for 2 min. Furthermore, after 6 min irradiation, the inactivation rates of HCoV-OC43 by SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS increase to 1.13 and 3.18-log10, respectively. In addition, the inactivation effects of SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS were also studied under an IR lamp at different power densities for 2 min. Compared to the low inactivation rate of HCoV-OC43 by SNF, SNF-Cu2-xS exhibit high inactivation rates which are determined to be 1.38, 1.54, and 2.09-log10 at 50, 100, and 200 mW cm−2 (Fig. S9a). Furthermore, the inactivation rates of PR8 by SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS were also investigated by tuning the power density and illumination time of the IR lamp. As expected, the SNF-Cu2-xS exhibit a stronger inactivation effect on PR8 than SNF under the same conditions. For instance, the inactivation rate of SNF-Cu2-xS is 3.93-log10 which is much higher than that (1.51-log10) of SNF under the IR illumination at 50 mW cm−2 for 6 min (Fig. 7b). In addition, under the IR lamp illumination at 50, 100, 200 mW cm−2 for 2 min, the inactivation rates by SNF-Cu2-xS are approximately 1.38, 1.81, 2.69-log10 (Fig. S9b). These results show the excellent antiviral activity of SNF-Cu2-xS under IR lamp irradiation.

Fig. 7.

Inactivation kinetics of a) HCoV-OC43 and b) PR8 by SNF or SNF-Cu2-xS upon IR lamp at 50 mW cm−2 for 2–6 min (***p < 0.001). c) TEM images of HCoV-OC43. d) TEM images of inactivated HCoV-OC43 after the treatment with SNF-Cu2-xS and IR lamp at 50 mW cm−2 for 2 min. e) A schematic diagram of morphology transformation of HCoV-OC43.

Meanwhile, we further evaluated the long-term antiviral efficacy of SNF-Cu2-xS without IR lamp irradiation. As shown in Fig. S9c, the inactivation rates of HCoV-OC43 by SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS are approximately 0.78 and 4.40-log10 after 2 h of interaction. Under the same conditions, the inactivation rates of PR8 by SNF and SNF-Cu2-xS are approximately 0.94 and 4.03-log10, respectively (Fig. S9d). To shed more light on the inactivation effect of the virus by SNF-Cu2-xS, we characterized the morphologies of HCoV-OC43 through TEM. As shown in Fig. 7c, the HCoV-OC43 viruses without treatment exhibit multiple surface spikes. However, after treatment with SNF-Cu2-xS and IR lamp at 50 mW cm−2 for 2 min, the surface spikes of the inactivated HCoV-OC43 viruses disappear (Fig. 7d), indicating the destruction of viruses. Fig. 7e vividly shows the schematic diagram of morphology transformation of HCoV-OC43. These results suggest that SNF-Cu2-xS have an excellent antiviral activity that is close to the literature [48], [54], [55].

The biosafety of mask plays a vital role in human health. To evaluate the toxicity of SNF-Cu2-xS, Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) were used as a normal cell to evaluate the cytotoxicity via 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). As shown in Fig. S10, the cell viability was higher than 114% and 132% after 24 h and 48 h incubation with SNF. Compared with SNF, SNF-Cu2-xS had low cytotoxicity, showing a survival rate of 86.4% at 24 h and 72.6% at 48 h, which reveals good biocompatibility of SNF-Cu2-xS.

Finally, the Cu2-xS-modified mask was re-assembled by using original SNF as the inner layer, original MNF as the middle layer and SNF-Cu2-xS as the outer layer. Aerosol filtration performances of the original disposable surgical mask and Cu2-xS-modified mask were investigated. Disposable surgical mask exhibited good filtration efficiency and low pressure drop, which were tested to be 82.8% and 27.4 Pa (Fig. S11). As expected, Cu2-xS-modified mask exhibited similar filtration efficiency of 82.3% and pressure drop of 27.1 Pa, indicating that the addition of Cu2-xS did not affect the filtration performance of the mask. After being irradiated by an IR lamp for 5 min (50 mW cm−2), the Cu2-xS-modified mask still has similar filtration performance, and the filtration efficiency is 81.6%. Good filtration performance of Cu2-xS-modified mask comes from the unchanged MNF layer. To explore the temperature distribution and cycle stability of Cu2-xS-modified masks, the outer layer (SNF-Cu2-xS) was directly illuminated by an IR lamp (50 mW cm−2). The temperatures of SNF-Cu2-xS layer and SNF layer were recorded by using the thermal camera (Fig. 8 a). For the SNF-Cu2-xS outer layer, its temperature goes up rapidly from 26 °C to 78 °C during 180 s, with the temperature elevation (ΔT) of 52 °C (Fig. 8b). Meantime, the equilibrium temperature of SNF-Cu2-xS layer exhibits no evident change during five cycles, demonstrating excellent cyclic stability. For the SNF inner layer, the temperature exhibits the low elevation from 27 °C to 42 °C (ΔT = 15 °C) during 0 to 180 s of irradiation (Fig. 8b), which has no obvious adverse effects on the human face. Especially, there is an obvious temperature difference between SNF-Cu2-xS layer (78 °C) and the SNF layer (42 °C). These results confirm the high photothermal effect and stability of Cu2-xS-modified masks with comfortability. Besides, the cost of Cu2-xS-modified masks was estimated to be approximately 0.17 Chinese Yuan per piece (Table S1).

Fig. 8.

a) Schematic illustration of Cu2-xS-modified mask illuminated by IR lamp. b) The temperature elevation curves of SNF-Cu2-xS layer and SNF layer under IR lamp stimulation.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have prepared SNF-Cu2-xS as the antibacterial and antiviral layer for assembling reusable facemasks. SNF-Cu2-xS have been successfully prepared via the one-step coprecipitation method, where the Cu2-xS nanoparticles were in-situ grown on the surface of SNF with the help of a commercial textile adhesion promoter. The obtained SNF-Cu2-xS exhibit strong NIR photoabsorption capacity, superior photothermal performance, and good stability. Importantly, both antibacterial and antiviral experiments demonstrate that SNF-Cu2-xS have excellent long-term antibacterial and antiviral effects. The antibacterial rate for E.coli and S. aureus can reach 99.9999% and 85.48% after 2 min of irradiation with an IR lamp at 200 mW cm−2. Compared to bare SNF, the inactivation of SNF-Cu2-xS possessed a sharp increase to 3.18 and 3.93-log10 against HCoV-OC43 and PR8 after 6 min exposure to IR lamp. The low cost, scalable production, mild virucidal conditions, and reusability make SNF-Cu2-xS become a powerful tool for daily-use protection amid the pandemic. It is foreseen that better performance will be achieved from future research inspired by this work, with masks fabricated by more advanced materials.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1201304), Major Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shandong Province (2019JZZY011108), Shanghai Shuguang Program (18SG29), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52161145406, 51972056), Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (20XD1420200), the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Scientific Research Project (21S11902600).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.136043.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Brown E.D., Wright G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529(7586):336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conlon B.P., Nakayasu E.S., Fleck L.E., LaFleur M.D., Isabella V.M., Coleman K., Leonard S.N., Smith R.D., Adkins J.N., Lewis K. Activated ClpP kills persisters and eradicates a chronic biofilm infection. Nature. 2013;503(7476):365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould I.M., Bal A.M. New antibiotic agents in the pipeline and how they can help overcome microbial resistance. Virulence. 2013;4(2):185–191. doi: 10.4161/viru.22507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taubenberger J.K., Morens D.M. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu. Rev. Pathol-Mech. 2008;3(1):499–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claas E.CJ., Osterhaus A.D., van Beek R., De Jong J.C., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Senne D.A., Krauss S., Shortridge K.F., Webster R.G. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351(9101):472–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parvez M.K., Parveen S. Evolution and Emergence of Pathogenic Viruses: Past, Present, and Future. Intervirology. 2017;60:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000478729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy S.B., Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 2004;10:122–129. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam S.J., O'Brien-Simpson N.M., Pantarat N., Sulistio A., Wong E.H.H., Chen Y.Y., Lenzo J.C., Holden J.A., Blencowe A., Reynolds E.C., Qiao G.G. Combating multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria with structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16162. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thapa R.K., Diep D.B., Tonnesen H.H. Topical antimicrobial peptide formulations for wound healing: Current developments and future prospects. Acta Biomater. 2020;103:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto A.M., Cerqueira M.A., Banobre-Lopes M., Pastrana L.M., Sillankorva S. Bacteriophages for Chronic Wound Treatment: From Traditional to Novel Delivery Systems. Viruses. 2020;12:235. doi: 10.3390/v12020235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.S.P. Smieszek, B.P. Przychodzen, M.H. Polymeropoulos, Amantadine disrupts lysosomal gene expression: A hypothesis for COVID19 treatment, Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55 (2020) 106004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.De Clercq E. Antiviral agents active against influenza A viruses. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5(12):1015–1025. doi: 10.1038/nrd2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson I.M., McHutchison J.G., Dusheiko G., Di Bisceglie A.M., Reddy K.R., Bzowej N.H., Marcellin P., Muir A.J., Ferenci P., Flisiak R., George J., Rizzetto M., Shouval D., Sola R., Terg R.A., Yoshida E.M., Adda N., Bengtsson L., Sankoh A.J., Kieffer T.L., George S., Kauffman R.S., Zeuzem S. Telaprevir for Previously Untreated Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364(25):2405–2416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snell L.M., McGaha T.L., Brooks D.G. Type I Interferon in Chronic Virus Infection and Cancer. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(8):542–557. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan L., Li J., Liu X.M., Cui Z.D., Yang X.J., Zhu S.L., Li Z.Y., Yuan X.B., Zheng Y.F., Yeung K.W.K., Pan H.B., Wang X.B., Wu S.L. Rapid Biofilm Eradication on Bone Implants Using Red Phosphorus and Near-Infrared Light. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1801808. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han D.L., Li Y., Liu X.M., Li B., Han Y., Zheng Y.F., Yeung K.W.K., Li C.Y., Cui Z.D., Liang Y.Q., Li Z.Y., Zhu S.L., Wang X.B., Wu S.L. Rapid bacteria trapping and killing of metal-organic frameworks strengthened photo-responsive hydrogel for rapid tissue repair of bacterial infected wounds. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;396 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo Y., Liu X.M., Tan L., Li Z.Y., Yeung K.W.K., Zheng Y.F., Cui Z.D., Liang Y.Q., Zhu S.L., Li C.Y., Wang X.B., Wu S.L. Enhanced photocatalytic and photothermal properties of ecofriendly metal-organic framework heterojunction for rapid sterilization. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;405 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao C., Xiang Y., Liu X., Cui Z., Yang X., Li Z., Zhu S., Zheng Y., Yeung K.W.K., Wu S. Repeatable Photodynamic Therapy with Triggered Signaling Pathways of Fibroblast Cell Proliferation and Differentiation To Promote Bacteria-Accompanied Wound Healing. ACS Nano. 2018;12(2):1747–1759. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han D.L., Li Y., Liu X.M., Yeung K.W.K., Zheng Y.F., Cui Z.D., Liang Y.Q., Li Z.Y., Zhu S.L., Wang X.B., Wu S.L. Photothermy-strengthened photocatalytic activity of polydopamine-modified metal-organic frameworks for rapid therapy of bacteria-infected wounds. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021;62:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceylan R.F., Ozkan B., Mulazimogullari E. Historical evidence for economic effects of COVID-19. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020;21(6):817–823. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01206-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou J., Hu Z., Zabihi F., Chen Z., Zhu M. Progress and Perspective of Antiviral Protective Material. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2020;2(3):123–139. doi: 10.1007/s42765-020-00047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saravolatz L.D., Depcinski S., Sharma M. Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir: Oral COVID Antiviral Drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022:ciac180. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li P., Wang Y., Lavrijsen M., Lamers M.M., de Vries A.C., Rottier R.J., Bruno M.J., Peppelenbosch M.P., Haagmans B.L., Pan Q. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res. 2022;32(3):322–324. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00618-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drozdzal S., Rosik J., Lechowicz K., Machaj F., Szostak B., Przybycinski J., Lorzadeh S., Kotfis K., Ghavami S., Los M.J. An update on drugs with therapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) treatment. Drug Resist. Updates. 2021;59 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2021.100794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang R., Li Y., Zhang A.L., Wang Y., Molina M.J. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Pro. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117(26):14857–14863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009637117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong H., Zhu Z., Lin J., Cheung C.F., Lu V.L., Yan F., Chan C.-Y., Li G. Reusable and Recyclable Graphene Masks with Outstanding Superhydrophobic and Photothermal Performances. ACS Nano. 2020;14(5):6213–6221. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alam Q., Schollbach K., Rijnders M., van Hoek C., van der Laan S., Brouwers H.J.H. The immobilization of potentially toxic elements due to incineration and weathering of bottom ash fines. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;379 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.120798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Z., Zhang Z., Lanzarini-Lopes M., Sinha S., Rho H., Herckes P., Westerhoff P. Germicidal Ultraviolet Light Does Not Damage or Impede Performance of N95 Masks Upon Multiple Uses. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7(8):600–605. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck S.E., Hull N.M., Poepping C., Linden K.G. Wavelength-Dependent Damage to Adenoviral Proteins Across the Germicidal UV Spectrum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52(1):223–229. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b04602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borkow G., Zhou S.S., Page T., Gabbay J. A Novel Anti-Influenza Copper Oxide Containing Respiratory Face Mask. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:11295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Si Y., Zhang Z., Wu W.R., Fu Q.X., Huang K., Nitin N., Ding B., Sun G. Daylight-driven rechargeable antibacterial and antiviral nanofibrous membranes for bioprotective applications. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:5931. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang P., Zhang Z., El-Moghazy A.Y., Wisuthiphaet N., Nitin N., Sun G. Daylight-Induced Antibacterial and Antiviral Cotton Cloth for Offensive Personal Protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12(44):49442–49451. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c15540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu N., Sun G., Zhu J. Photo-induced self-cleaning functions on 2-anthraquinone carboxylic acid treated cotton fabrics. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:15383–15390. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen W., Chen J., Li L., Wang X., Wei Q., Ghiladi R.A., Wang Q. Wool/Acrylic Blended Fabrics as Next-Generation Photodynamic Antimicrobial Materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(33):29557–29568. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b09625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Oliveira M.C.A., da Silva F.A.G., da Costa M.M., Rakov N., de Oliveira H.P. Curcumin-Loaded Electrospun Fibers: Fluorescence and Antibacterial Activity. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2020;2:256–264. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S., Li J.N., Cao Y.H., Gu J.W., Wang Y.F., Chen S.G. Non-Leaching, Rapid Bactericidal and Biocompatible Polyester Fabrics Finished with Benzophenone Terminated N-halamine. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2021;10:119–128. doi: 10.1007/s42765-021-00100-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang L., Gu M., Wang Z., Tang T.W., Zhu Z., Yuan Y., Wang D., Shen C., Tang B.Z., Ye R. Highly Efficient and Rapid Inactivation of Coronavirus on Non-Metal Hydrophobic Laser-Induced Graphene in Mild Conditions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31(24):2101195. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202101195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X., Liang H., Li H., Xia Y., Zhu X., Peng L., Zhang W., Liu L., Zhao T., Wang C., Zhao Z., Hung C.-T., Zagho M.M., Elzatahry A.A., Li W., Zhao D. Sequential Chemistry Toward Core-Shell Structured Metal Sulfides as Stable and Highly Efficient Visible-Light Photocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59(8):3287–3293. doi: 10.1002/anie.201913600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang N., Gao C., Han Y.u., Huang X., Xu Y., Cao X. Detection of human immunoglobulin G by label-free electrochemical immunoassay modified with ultralong CuS nanowires. J. Mat. Chem. B. 2015;3(16):3254–3259. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01881h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X.Y., Zhang G.N., Zhang H.Y., Liu X.P., Shi J., Shi H.X., Yao X.H., Chu P.K., Zhang X.Y. A bifunctional hydrogel incorporated with CuS@MoS2 microspheres for disinfection and improved wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;382 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou M., Tian M., Li C. Copper-Based Nanomaterials for Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016;27(5):1188–1199. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y., Xiao Y., Cao Y., Guo Z., Li F., Wang L. Construction of Chitosan-Based Hydrogel Incorporated with Antimonene Nanosheets for Rapid Capture and Elimination of Bacteria. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020;30:2003196. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carratalà A., Bachmann V., Julian T.R., Kohn T. Adaptation of Human Enterovirus to Warm Environments Leads to Resistance against Chlorine Disinfection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(18):11292–11300. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c03199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warnes S.L., Keevil C.W. Mechanism of copper surface toxicity in vancomycin-resistant enterococci following wet or dry surface contact. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77(17):6049–6059. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00597-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Z., Yu N., Li X., Yu W., Han S., Ren X., Yin S., Li M., Chen Z. Galvanic Exchange-induced Growth of Au Nanocrystals on CuS Nanoplates for Imaging Guided Photothermal Ablation of Tumors. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;381 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coyle G.J., Tsang T., Adler I., Yin L. XPS studies of ion-bombardment damage of transition metal sulfides. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1980;20(2):169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Folmer J.C.W., Jellinek F., Calis G.H.M. The electronic-structure of pyrites, particularly CuS2 and Fe1-xCuxSe2 - an XPS and mossbauer study. J. Solid State Chem. 1988;72:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warnes S.L., Little Z.R., Keevil C.W., Colwell R. Human Coronavirus 229E Remains Infectious on Common Touch Surface Materials. mBio. 2015;6(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01697-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang L., Xu S., Wang Z., Xue K.e., Su J., Song Y., Chen S., Zhu C., Tang B.Z., Ye R. Self-Reporting and Photothermally Enhanced Rapid Bacterial Killing on a Laser-Induced Graphene Mask. ACS Nano. 2020;14(9):12045–12053. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J.F., Ma L.L., Li Z.Y., Liu X.M., Zheng Y.F., Liang Y.Q., Liang C.Y., Cui Z.D., Zhu S.L., Wu S.L. Oxygen Vacancies-Rich Heterojunction of Ti3C2/BiOBr for Photo-Excited Antibacterial Textiles. Small. 2022;18:2104448. doi: 10.1002/smll.202104448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao C., Xiang Y., Liu X., Cui Z., Yang X., Yeung K.W.K., Pan H., Wang X., Chu P.K., Wu S. Photo-Inspired Antibacterial Activity and Wound Healing Acceleration by Hydrogel Embedded with Ag/Ag@AgCl/ZnO Nanostructures. ACS Nano. 2017;11(9):9010–9021. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamayo L., Azocar M., Kogan M., Riveros A., Paez M. Copper-polymer nanocomposites: An excellent and cost-effective biocide for use on antibacterial surfaces. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. 2016;69:1391–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergemann C., Zaatreh S., Wegner K., Arndt K., Podbielski A., Bader R., Prinz C., Lembke U., Nebe J.B. Copper as an alternative antimicrobial coating for implants - An in vitro study. World J. Transplant. 2017;7:193–202. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v7.i3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borkow G., Sidwell R.W., Smee D.F., Barnard D.L., Morrey J.D., Lara-Villegas H.H., Shemer-Avni Y., Gabbay J. Neutralizing viruses in suspensions by copper oxide-based filters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51(7):2605–2607. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00125-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gu M.J., Huang L.B., Wang Z.Y., Guo W.H., Cheng L., Yuan Y.C., Zhou Z., Hu L., Chen S.J., Shen C., Tang B.Z., Ye R.Q. Molecular Engineering of Laser-Induced Graphene for Potential-Driven Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial and Antiviral Applications. Small. 2021;17:2102841. doi: 10.1002/smll.202102841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.