Abstract

Background

Given future challenges in conducting large randomized, placebo controlled trials for future CF therapeutics development, we evaluated the potential for using external historical controls to either enrich or replace traditional concurrent placebo groups in CF trials

Methods

The study included data from sequentially completed, randomized, controlled clinical trials, EPIC and OPTIMIZE respectively, evaluating optimal antibiotic therapy to reduce the risk of pulmonary exacerbation in children with early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. The primary treatment effect in OPTIMIZE, the risk of pulmonary exacerbation associated with azithromycin, was re-estimated in alternative designs incorporating varying numbers of participants from the earlier trial (EPIC) as historical controls. Bias and precision of these estimates were characterized. Propensity scores were derived to adjust for baseline differences across study populations, and both Poisson and Cox regression used to estimate treatment efficacy.

Results

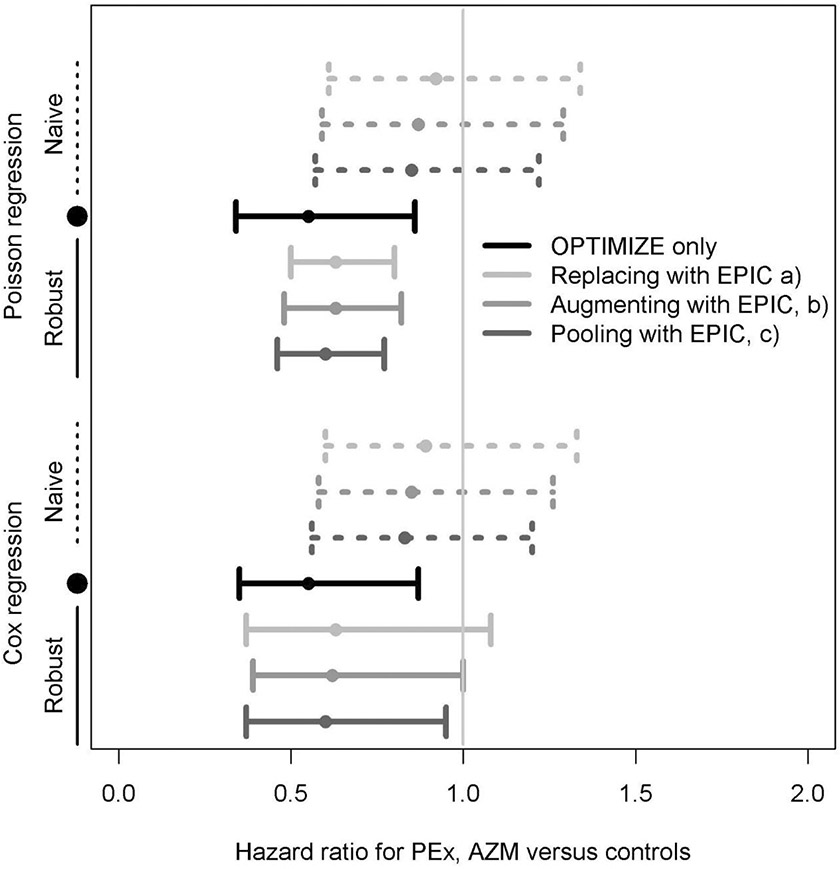

Replacing 86 OPTIMIZE placebo participants with 304 controls from EPIC to mimic a fully historically controlled trial resulted an 8% reduction in risk of pulmonary exacerbations (Hazard ratio (HR):0.92 95% CI 0.61, 1.34) when not adjusting for key baseline differences between study populations. After adjustment, a 37% decrease in risk of exacerbation (HR:0.63, 95% CI 0.50,0.80) was estimated, comparable to the estimate from the original trial comparing the 86 placebo participants to 77 azithromycin participants on azithromycin (45%, HR:0.55, 95% CI: 0.34,0.86). Other adjusted approaches provided similar estimates for the efficacy of azithromycin in reducing exacerbation risk: pooling all controls from both studies provided a HR of 0.60 (95%CI 0.46, 0.77) and augmenting half the OPTIMIZE placebo participants with EPIC controls gave a HR 0.63 (95% CI 0.48, 0.82).

Conclusions

The potential exists for future CF trials to utilize historical control data. Careful consideration of both the comparability of controls and of optimal methods can reduce the potential for biased estimation of treatment effects.

Keywords: real world data, external controls, pulmonary exacerbations, clinical development

Introduction

The development pipeline for cystic fibrosis (CF) therapeutics has produced remarkable successes over the last two decades, most recently with the regulatory approvals of novel modulator therapies aimed at restoring function of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein (1, 2). Despite these advances, the need for new therapeutics remains due to considerable heterogeneity in the underlying disease severity across the CF population, the absence of long term data on the impact of highly effective modulators such as elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor (ETI) on safety, morbidity and mortality outcomes, and the lack of global regulatory approval of and access to these effective therapies (3). Clinical development of additional new CF therapies is challenged, however, by smaller populations for whom significant treatment benefit is likely to be observed as access to ETI grows, impacting both the projected efficacy of a new therapy and the size of the optimal target population for development.

The feasibility of traditional, randomized, placebo-controlled, trials in CF has relied upon participant willingness to be randomized to placebo and the potential for robust treatment benefit beyond the standard of care. These aspects may no longer hold for future development efforts, and thus it is necessary to consider alternative study designs for the evaluation of new therapies. Studies of new interventions, particularly in the rare disease setting, are increasingly taking place without incorporating randomized trials. In 2014, Downing reported that 13% (58 of 448) of drugs approved by the FDA over the preceding decade did so in the absence of placebo comparators (4). The broad class of evidence used in some of these non-randomized trials has been termed real-world evidence (RWE), or evidence coming from real-world data (RWD). RWD originates from a variety of sources which may include historical clinical trials but may also come from observational studies or from records involving the routine delivery of health care (5). While study designs incorporating external controls have rarely been used in the setting of CF clinical development, these designs may prove to be an attractive means of streamlining development, contingent on the reliability of methods and data that will ensure unbiased treatment effect estimation. (6, 7).

Late phase clinical trials in cystic fibrosis (CF) spanning multiple therapeutic classes have consistently relied on the incidence rate of pulmonary exacerbation (PEx) as a key clinical outcome (8). Many of these trials are powered to target the detection of clinically meaningful differences between treatment groups with respect to PEx regardless of whether this endpoint is a primary or secondary endpoint, recognizing its importance in context of the disease (9). Due to relatively low rates of PEx events, expected to decrease further with expansion of ETI into standard of care (1, 2, 10), large sample sizes are consistently required for sufficient statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences (8, 11). Novel study design approaches to assess the efficacy of new interventions in reducing PEx must therefore be considered.

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the use of external historical controls to either enrich or replace traditional concurrent placebo groups in CF trials, with focus on estimation of treatment effects for the PEx endpoint. Leveraging data from two sequential CF clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of early antibiotic therapy in children with CF and early Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) infection, we evaluated the bias and precision of treatment effect estimates derived from alternative study designs utilizing historical rather than concurrent controls. Our hypothesis is that modern statistical methods will enable precise and unbiased estimation of the risk of PEx in trial designs utilizing fewer concurrent placebo controls and increased external controls. This proof of concept study provides a foundation for the consideration of study designs utilizing external controls to evaluate PEx and other CF outcomes.

Methods

Study Population

The Early Pa Infection Control Trial (EPIC) and Optimizing Treatment for Early Pa Infection (OPTIMIZE) randomized trials, conducted from 2004-2009 and 2014-2017 respectively, both evaluated optimal antibiotic regimens for the treatment of early Pa infection in children with CF. Both trials utilized a key efficacy endpoint derived from a common definition of PEx requiring antibiotic therapy (12, 13). The primary aim of the EPIC trial was to evaluate whether more vs. less aggressive inhaled antibiotic treatment with tobramycin reduced the risk of PEx (13), whereas the primary aim of the OPTIMIZE trial was to determine whether azithromycin as compared to placebo reduced the risk of PEx (12).

EPIC and OPTIMIZE both enrolled CF children with new onset Pa having similar eligibility criteria (12, 13); however EPIC enrolled children 1 to 12 years of age and OPTIMIZE 6 months to 18 years of age. To standardize eligibility for this study, subjects <1 year of age and >12 were removed from OPTIMIZE. All randomized EPIC trial participants were eligible for use as historical controls regardless of treatment assignment, as no treatment differences were observed with respect to PEx within this trial (13). Additional comparability of EPIC trial participants to OPTIMIZE participants was assessed using criteria provided by Pocock (Table 1) (14). The OPTIMIZE trial was stopped early due to efficacy based on the primary PEx endpoint and resulted in a median follow-up time of 12 months, whereas EPIC trial participants were followed a median of 16 months (12).

Table 1.

Evaluation of the general conditions needed before combining historical and concurrent controls as recommended by Pocock (14). Many, but not all, of the conditions are met.

| Condition | Comparison of EPIC and OPTIMIZE Trials |

|---|---|

| Standardized treatment | Standard of care therapy for new onset Pa among all participants over the duration of follow-up included inhaled tobramycin. Differing intensities of treatment regimen with inhaled tobramycin with or without ciprofloxacin among historical controls were shown to have no impact on outcomes, enabling use of all EPIC trial participants and comparability of early Pa treatment between OPTIMIZE and EPIC studies (12, 13). |

| Recent time interval | Trials were completed within the same decade with no major changes in treatment for early Pa infection over this time |

| Common method of evaluation | The same definition was used to define pulmonary exacerbation across trials (12, 13). |

| Common patient characteristics | Major eligibility criteria match, requiring: |

| Performed by same organization | Both trials were implemented at participating sites in the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network (CF TDN) |

| No systematic confounding | Standard of care was similar between cohorts except:

|

Pa = Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Full eligibility and exclusion criteria are available for EPIC and OPTIMIZE studies here (12, 25).

OPTIMIZE participants could be aged 6mo to 18 years, so children outside the range of EPIC participants were excluded.

EPIC participants were required to have this recent positive culture within 6 months, for OPTIMIZE the window was shortened to 40 days.

EPIC participants could have no more than 1 previous course of anti-Pa antibiotics over the past two years, and neither study could have macrolide therapy use within the past 30 days.

Study Designs

Three study designs were retrospectively considered as alternatives to the original OPTIMIZE trial design, to derive treatment effect estimates of the risk of PEx utilizing the historical controls: (1) Pooling: combining all available participants from both studies to increase the size of the OPTIMIZE control group, (2) Augmenting: omitting half the OPTIMIZE participants randomized to placebo and augmenting the OPTIMIZE control group with all EPIC historical controls, (3) Replacing: omitting all OPTIMIZE participants randomized to placebo and replacing with all EPIC historical controls. The pooling approach assesses whether the power would be increased for the primary analysis by incorporating historical controls and increasing the size of the OPTIMIZE control group. The augmenting approach assesses the potential to reduce the original placebo arm by half, and the replacing approach assesses whether an active arm only trial could have been used, with the historical trial participants as the only controls.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between EPIC and OPTIMIZE in baseline characteristics known to be associated with risk of PEX were descriptively summarized (15-17). Available risk factors included age, race, sex, morphometrics, CFTR genotype, comorbidities (asthma, diabetes, liver disease), baseline forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) status, history of PEx and respiratory infections, and current chronic use of dornase alfa and hypertonic saline. All available measures were included a priori in computation of propensity scores for the probability of being in each study, regardless of statistical significance, (save those binary variables for which more than 95% of participants had an identical response). Scores were then used in subsequent modeling described below to derive treatment effect estimates (18). Age and FEV1 were categorized to avoid having to assume linearity, as was done in the primary study analyses.

Risk of PEx associated with azithromycin use in OPTIMIZE as compared to control was estimated for each study design scenario using the original analytic approach specified in the trial: age-adjusted Cox proportional hazards modeling of time to first PEx. Poisson regression for risk of the first PEx event was included as an alternative, fully-parametric, estimation approach for an approximated hazard ratio to compare precision and bias of treatment effect estimates (19). For both regression approaches, naïve treatment effect estimates were derived not accounting for baseline differences between EPIC and OPTIMIZE study populations, as well as robust estimates. The robust estimates implement inverse weighting by propensity scores, an approach which effectively balances EPIC and OPTIMIZE participants with respect to baseline characteristics, making differences between treatment arms interpretable (20, 21). Treatment effect estimates (hazard ratios [HRs]) for all approaches are provided with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. For the augmenting approach, we aimed to represent the case where only half the OPTIMIZE controls are used. We randomly selected 50% of the OPTIMIZE controls without replacement 20 times, and for each dataset estimated the treatment effect and precision. We combined these 20 estimates using multiple imputation methods developed by Rubin (22)

Results

Study Population and Baseline Characteristics

All 304 EPIC trial participants and 163 of 221 (75%) of OPTIMIZE trial participants (77 azithromycin arm, 86 placebo) were included in our analysis after age-restriction. Baseline characteristics between study populations are provided in Table 2. There were some notable differences between study populations: OPTIMIZE participants were more likely to chronically use hypertonic saline (35.6% vs 4.3%), and modulators (10.5% vs 0.0%) due to the timing of the trial in relation to changing standard of care. OPTIMIZE participants were taller for their age (height z-score −0.30 vs −0.50), used more dornase alfa (65.6% vs 53.6%), and more likely to have Pa detected at baseline (44.2% vs 38.8%). No large differences were identified between the study cohorts by genotype, sex, or baseline FEV1.

Table 2:

Baseline characteristics by study population

| Baseline Characteristic | EPIC (N=304) |

Optimize (N=163) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 154 (50.7) | 80 (49.1) | 0.82 |

| Race or Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.012 | ||

| White | 285 (93.8) | 144 (88.3) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (1.3) | 11 (6.7) | |

| Black | 7 (2.3) | 6 (3.7) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Other | 7 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 5.70 (3.51) | 5.84 (3.45) | 0.67 |

| Age (years) category, n (%) | 0.51 | ||

| 1-3 | 71 (23.4) | 45 (27.6) | |

| >3 to 6 | 109 (35.9) | 59 (36.2) | |

| >6 to 12 | 124 (40.8) | 59 (36.2) | |

| Genotype, n (%) | 0.65 | ||

| Delta F508 Heterozygous | 149 (49.0) | 86 (52.8) | |

| Delta F508 Homozygous | 116 (38.2) | 62 (38.0) | |

| Other | 33 (10.9) | 12 (7.4) | |

| Unknown | 6 (2.0) | 3 (1.8) | |

| Height for age z-score, mean (SD) | −0.50 (0.93) | −0.30 (1.02) | 0.032 |

| Weight for age z-score, mean (SD) | −0.33 (0.95) | −0.18 (1.04) | 0.11 |

| FEV1pp*, mean (SD) | 96.18 (16.68) | 94.13 (16.59) | 0.34 |

| FEV1pp* category, n (%) | 0.50 | ||

| < 6 years of age | 173 (56.9) | 91 (55.8) | |

| <90% predicted | 40 (13.2) | 24 (14.7) | |

| ≥ 90% predicted | 87 (28.6) | 48 (29.4) | |

| Chronic dornase alfa use, n (%) | 163 (53.6) | 107 (65.6) | 0.016 |

| Chronic hypertonic saline use, n (%) | 13 (4.3) | 58 (35.6) | <0.001 |

| Any previous CFTR modulator use, n (%) | 0 (0) | 17 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| CF related diabetes, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 1 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 51 (16.8) | 16 (9.8) | 0.057 |

| Pa positive at enrollment¥, n (%) | 118 (38.8) | 72 (44.2) | 0.009 |

| Prior history of isolation of Pa, n (%) | 96 (31.6) | 64 (39.3) | 0.12 |

| Randomized to azithromycin | 0 (0%) | 77 (47%) | NA |

Pa = Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Note that not all study participants have Pa detected at baseline, as the enrollment study visit takes place after eligibility is determined via a clinically-obtained swab. Pa was more common at baseline in OPTIMIZE due to a shorter time interval since the qualifying positive swab (Table 1). Measures in bold were included in propensity score computation a priori based on plausible association with CF health outcomes.

FEV1 was not measured for participants < 6 years of age, so its value is only reported for older children. FEV1pp = forced expiratory volume in one second as a percentage of predicted; CFTR= Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator

The propensity score was computed using the bolded variables in table 2. Cutting off at a 0.5 threshold, the propensity score correctly classified 75%, 81% and 84% of participants by study of origin (EPIC versus OPTIMIZE) in the pooling, augmenting, and replacing study design scenarios.

Treatment Effect Estimation Across Study Designs

In the original OPTIMIZE trial including the full, non age-restricted randomized cohort, there was a significant 44% reduction in risk of PEx associated with azithromycin as compared to placebo (12). This finding was replicated in our age-restricted study population, with a 45% reduction in risk of PEx among 77 OPTIMIZE azithromycin participants as compared to 86 OPTIMIZE placebo participants using age-adjusted Cox regression (HR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.35, 0.87, p=0.01). Estimation of the treatment effect using Poisson regression was comparable (HR: 0.55, 95% CI 0.34, 0.86, p=0.01).

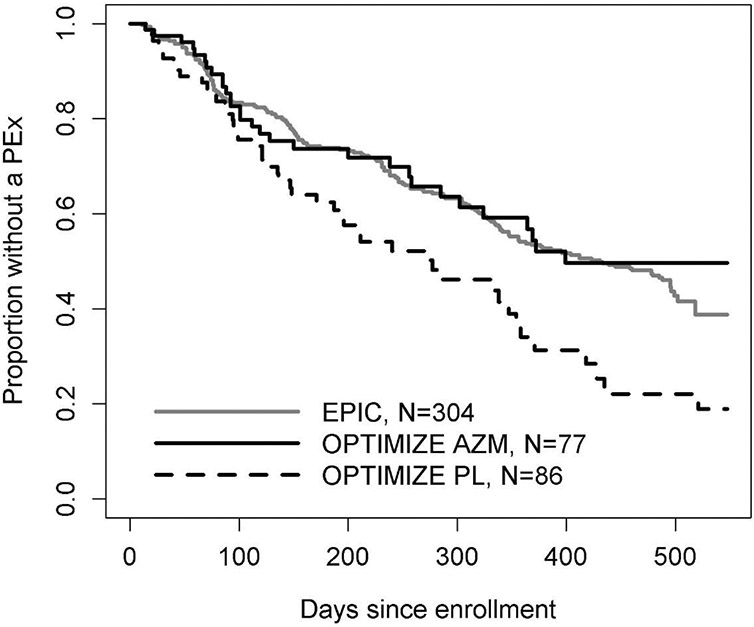

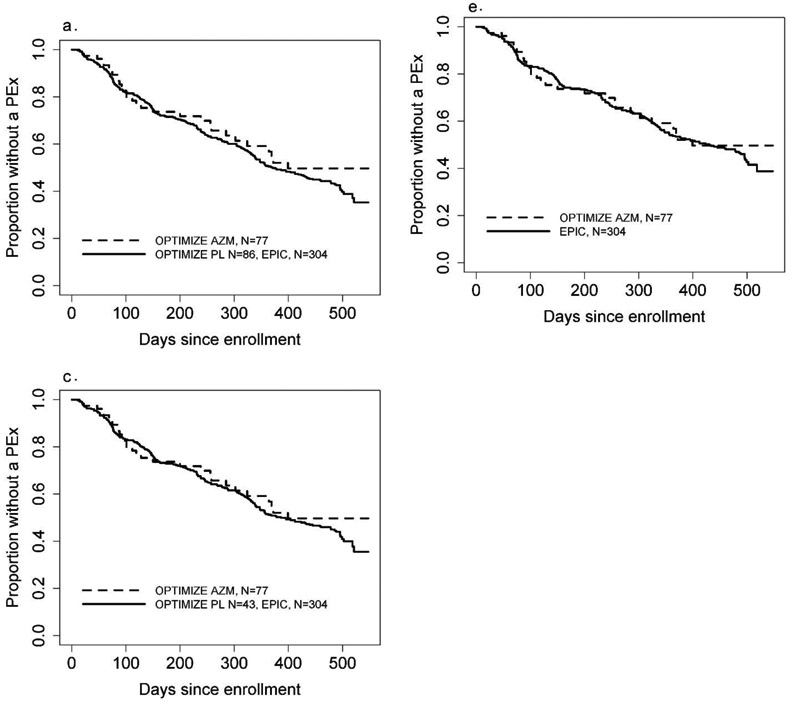

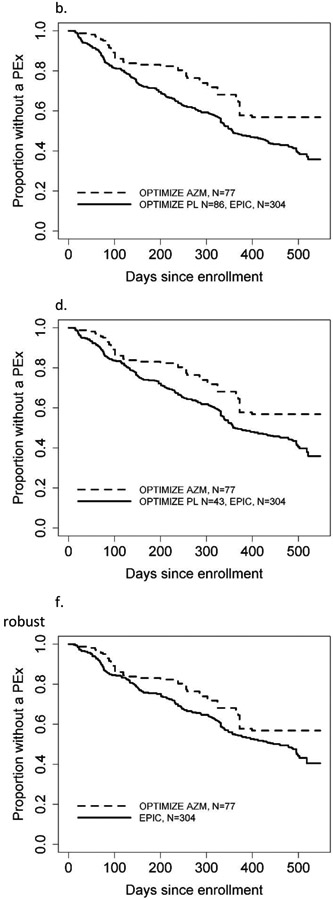

Treatment effect estimates derived under the pooling, augmenting, and replacing study design scenarios are provided in Table 3 utilizing the different regression approaches. The naïve regression approaches performed poorly across all three study design scenarios utilizing EPIC controls, as they did not account for differences between study populations. Figure 1 displays the Kaplan-Meier curve for the time to first PEx across study populations, exhibiting the differences in risk of PEx between EPIC controls and OPTIMIZE control participants that led to the altered treatment effect estimates. However, robust regression approaches which accounted for baseline differences between study populations produced less biased treatment effect estimates nearing the original trial estimates and were only slightly more conservative ranging from a 37-40% reduction in PEx risk (Table 3 and Figures 2a-2f). Thus, the differences in PEx risk between EPIC controls and OPTIMIZE control participants could be largely explained by the baseline factors comprised by the propensity score.

Table 3.

Treatment effect estimates for the effect of azithromycin on PEx estimated across study design scenarios and with varying regression methods.

| Treatment Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design Scenarios | OPTIMIZE AZM (n=77) vs. |

Cox Regression HR (95%CI) p-value |

Poisson Regression HR (95% CI) p-value |

||

| Naive1 | Robust2 | Naive1 | Robust2 | ||

| OPTIMIZE Only | N=86 OPTIMIZE Placebo | 0.55 (0.35, 0.87) p=0.01 |

N/A | 0.55 (0.34, 0.86) p=0.01 |

N/A |

| Pooling OPTIMIZE with EPIC | N=86 OPTIMIZE Placebo with N=304 EPIC | 0.83 (0.56, 1.20) p=0.33 |

0.60 (0.37, 0.95) p=0.03 |

0.85 (0.57, 1.22) p=0.40 |

0.60 (0.46, 0.77) p<0.001 |

| Augmenting OPTIMIZE with EPIC 3 | N=43 OPTIMIZE Placebo with N=304 EPIC | 0.85 (0.58, 1.26) p=0.43 |

0.62 (0.39, 1.00) p=0.054 |

0.87 (0.59, 1.29) p=0.51 |

0.63 (0.48, 0.82) p<0.001 |

| Replacing OPTIMIZE with EPIC | N=0 OPTIMIZE Placebo with N=304 EPIC | 0.89 (0.60, 1.33) p=0.58 |

0.63 (0.37, 1.08) p=0.09 |

0.92 (0.61, 1.34) p=0.69 |

0.63 (0.50, 0.80) p<0.001 |

AZM= Azithromycin; HR= Hazard Ratio

Naive approach does not account for baseline differences between EPIC and OPTIMIZE study populations.

Robust approach accounts for baseline differences between EPIC and OPTIMIZE study populations using inverse probability weighting (IPW).

Results presented are based on the average of 20 repetitions of sampling 50% of OPTIMIZE control participants.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to first pulmonary exacerbation by study, and by treatment arm within OPTIMIZE. Note that a higher proportion EPIC participants are free of PEx, relative to the OPTIMIZE placebo arm. AZM = azithromycin, PL = placebo.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to first pulmonary exacerbation across study design scenarios and comparing naïve vs. robust methods. In each graph, the dashed curve shows AZM and the solid line shows the control group, which may combine both EPIC and OPTIMIZE. The augmenting approach figure is an example curve from one of the 20 repetitions. AZM = azithromycin, PL = placebo.

a. Pooling all EPIC and OPTIMIZE, naïve

b. Pooling all EPIC and OPTIMIZE, robust

c. Augmenting OPTIMIZE with EPIC, naïve

d. Augmenting OPTIMIZE with EPIC, robust

e. Replacing OPTIMIZE controls with EPIC, naïve

f. Replacing OPTIMIZE controls with EPIC, robust

Designs incorporating EPIC (historical) controls and robust Poisson regressions produced more efficient estimates of the treatment effect with smaller confidence intervals and more significant p-values (Figure 3). Pooling EPIC controls with OPTIMIZE placebo participants and adjusting for baseline differences gave the treatment effect estimate closest to the fully placebo-controlled design, and allowed precision gains, however without decreasing the burden of prospective patient recruitment. The augmenting and replacement designs, in comparison, demonstrated the potential for considerable decreases in the need for concurrent placebo controls by n=43 and 86 participants, respectively. The robust HR comparing OPTIMIZE azithromycin participants to EPIC controls utilizing the replacement study design was 0.63 (95% CI 0.50,0.80, p<0.001), and would have led to comparable albeit slightly more conservative findings to the fully placebo controlled study design. Robust Cox regression estimates of treatment efficacy had wider confidence intervals overall compared to robust Poisson regression.

Figure 3.

Treatment effect estimates for the effect of azithromycin on first PEx. Estimates are derived using the OPTIMIZE azithromycin arm (N=77) vs. OPTIMIZE only placebo controls (n=86), or by (a) replacing 86 OPTIMIZE placebo participants with 304 EPIC historical controls, (b) augmenting 43 placebo participants with 304 EPIC historical controls, or c) pooling all 86 OPTIMIZE placebo participants with 304 EPIC historical controls.

Discussion

While randomized, placebo-controlled trials remain the gold standard, this design may be challenged in the future landscape of CF clinical development. With the decreasing frequency of PEx across the CF population expected with long term establishment of ETI, controlled trials with this endpoint will require over 2000 patients for sufficient power to estimate the modest effect sizes anticipated from a new therapy over this lower baseline PEx incidence (10). Even greater challenges exist with the development of new CFTR modulator therapies, for which placebo-controlled trials may not be ethically feasible so long as they require individuals on established and effective modulator therapy to withdraw from this new standard of care medication. Therefore in addition to pursuing new clinical trial endpoints, we must also explore alternative study designs that may serve to complement traditional clinical development paths and rely less heavily on placebo controls (3). This proof of concept study demonstrates the potential for integration of external control data in future CF trial designs.

Using treatment trials for early Pa infection, we found that data from historical controls could be used in one of three different design scenarios for a future trial; and two scenarios significantly decreased the required sample size of concurrent placebo participants. In this study, we demonstrated a maximal reduction of 86 (~50%) in the number needed to enroll, relative to the fully randomized design. Despite differences in baseline characteristics and control group PEx rates between the two studies, the use of robust methods utilizing propensity score weighting balanced the two study cohorts with respect to baseline characteristics, and ultimately mitigated the bias in the estimated treatment effect that when incorporating historic controls into the original trial. This finding is particularly important as it is unlikely that future historical control groups and the concurrent study population will identically match in terms of baseline characteristics. While we demonstrated that some of Pocock’s criteria for study similarity were met, there were substantial deviations at baseline; and efficacy estimates that did not adjust for these differences were not comparable to those of the randomized trial. A further finding from our study was the improvement in precision with the use of Poisson rather than Cox regression to estimate the effect of azithromycin on risk of the first PEx. Future studies over more study settings are needed to assess the generalizability of this precision benefit, which may be due to parametric versus semi-parametric modeling.

This study has several limitations. First, the study populations had notable differences at baseline that could only be accounted for with measurable study data collected similarly between trials. This study was not able to include all baseline factors found previously to be associated with risk of exacerbations, such as certain chronic medications and history of Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (15-17). In our study, we utilized historical controls from both treatment arms from a prior clinical trial in which no treatment difference was found. However, in order to reduce bias, future applications may require the standard treatment received among the historical controls to be identical to that of the active comparator. Another limitation of this study is that it was conducted in a post-hoc fashion, whereas future trial planning considering the use of historical controls will not have the ability to compare treatment effect estimates to a fully randomized trial. However, adaptive designs utilizing Bayesian methodologic approaches may be feasible in future trial designs, which enable evaluation of the comparability of historical controls in an ongoing fashion throughout the trial. At interim analyses in such adaptive studies, should the historical and concurrent controls be dissimilar in eligibility or baseline characteristics, study investigators could increase or decrease the proportion randomized to placebo in the currently enrolled cohort, or could adjust the maximum sample size (23, 24). These more complex designs require further exploration and simulation for the CF trial design setting to compare their efficiency and accuracy for estimation of treatment effects with the fixed design scenarios presented in this paper. Lastly, our study focused on the primary study endpoint PEx and did not assess secondary or safety outcomes. Further work is needed to determine how best to evaluate the use of historical controls on the overall study conclusions across all study endpoints.

In summary, our study has retrospectively demonstrated the potential for a CF clinical trial to have been conducted with fewer concurrent control patients with the use of historical controls from a prior, similar trial. These findings provide encouragement for the consideration of historically controlled trials in CF when randomized, controlled clinical trials are no longer feasible. In future work, we will assess how comparable studies need to be in order to achieve consistent treatment effect estimates for the outcome of interest. These approaches require thoughtful consideration, however, of potential confounding factors including systematic differences in either standards of care or in underlying risk of disease over time. An added resource that will prove critical in this effort is the linkage of trial data with data from the CF Patient Registry, which could be used either as a source of control data itself pending comparability of data sources as outlined by Pocock (14), or alternatively as a source of data to enrich baseline study characteristics for adjustment purposes.

While the road ahead for CF clinical development is likely to be challenging with an ever-changing landscape of CF clinical care, this study provides an important step towards identifying new approaches for clinical trial design. These designs are needed to ensure continued development of safe and effective therapies and to ensure maximal improvements in the health of individuals with CF.

Highlights.

With increasing access to modulators, placebo-controlled trials are less feasible

Real-world evidence may provide a feasible comparison for evaluating novel therapies

We provide an example of including controls from a historical trial into a later trial

Accounting for study differences, estimates of treatment efficacy match the original

Acknowledgments

The investigators wish to thank the EPIC and OPTIMIZE trial participants and their families who made this research possible.

Funding Source:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants U01HL114623, U01HL114589. P30 DK 089507, UL1 TR002319.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit author statement

Amalia Magaret: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, writing – original draft. Mark Warden: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft. Noah Simon: supervision, methodology, writing – review & editing. Sonya Heltshe: supervision, writing – review & editing. George Z. Retsch-Bogart: investigation, writing – review & editing. Bonnie W. Ramsey: Funding acquisition, investigation, writing – review & editing. Nicole Mayer-Hamblett: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft.

References

- 1.Middleton PG, Mall MA, Drevinek P. Elexacaftor–Tezacaftor–Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. New Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heijerman HGM, McKone EF, Downey DG. Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer-Hamblett N, van Koningsbruggen-Rietschel S, Nichols DP, VanDevanter DR, Davies JC, Lee T, Durmowicz AG, Ratjen F, Konstan MW, Pearson K, Bell SC, Clancy JP, Taylor-Cousar JL, De Boeck K, Donaldson SH, Downey DG, Flume PA, Drevinek P, Goss CH, Fajac I, Magaret AS, Quon BS, Singleton SM, VanDalfsen JM, Retsch-Bogart GZ. Building global development strategies for cf therapeutics during a transitional cftr modulator era. J Cyst Fibros 2020; 19: 677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, Krumholz HM, Ross JS. Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005-2012. JAMA 2014; 311: 368–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Framework for FDA’s Real-World Evidence Program. https://www.fda.gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/real-world-evidence: FDA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer-Hamblett N Challenging Clinical Trial Design Precedence in the Highly Effective Modulator Era. Pediatric Pulmonology 2019; 54: S111–S112. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magaret AS, Warden M, Simon NR, Heltshe SL, Mayer-Hamblett N. Real-world evidence in cystic fibrosis modulator development: establishing a path forward. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2020; 19: e11–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.VanDevanter DR, Hamblett NM, Simon N, McIntosh J, Konstan MW. Evaluating assumptions of definition-based pulmonary exacerbation endpoints in cystic fibrosis clinical trials. J Cyst Fibros 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols DP, Durmowicz AG, Field A, Flume PA, VanDevanter DR, Mayer-Hamblett N. Developing Inhaled Antibiotics in Cystic Fibrosis: Current Challenges and Opportunities. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019; 16: 534–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griese M, Costa S, Linnemann RW, Mall MA, McKone EF, Polineni D, Quon BS, Ringshausen FC, Taylor-Cousar JL, Withers NJ, Moskowitz SM, Daines CL. Safety and Efficacy of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor for ≥24 Weeks in People With CF and ≥1 F508del Allele: Interim Results of an Open-Label Phase Three Clinical Trial. Am J Resp Crit Care 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandevanter DR, Yegin A, Morgan WJ, Millar SJ, Pasta DJ, Konstan MW. Design and powering of cystic fibrosis clinical trials using pulmonary exacerbation as an efficacy endpoint. J Cyst Fibros 2011; 10: 453–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer-Hamblett N, Retsch-Bogart G, Kloster M, Accurso F, Rosenfeld M, Albers G, Black P, Brown P, Cairns A, Davis SD, Graff GR, Kerby GS, Orenstein D, Buckingham R, Ramsey BW, Group OS. Azithromycin for Early Pseudomonas Infection in Cystic Fibrosis. The OPTIMIZE Randomized Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 198: 1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treggiari MM, Retsch-Bogart G, Mayer-Hamblett N, Khan U, Kulich M, Kronmal R, Williams J, Hiatt P, Gibson RL, Spencer T, Orenstein D, Chatfield BA, Froh DK, Burns JL, Rosenfeld M, Ramsey BW, Early Pseudomonas Infection Control I. Comparative efficacy and safety of 4 randomized regimens to treat early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011; 165: 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pocock SJ. The combination of randomized and historical controls in clinical trials. Journal of Chronic Diseases 1976; 29: 175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanDevanter DR, Pasta DJ, Konstan MW. Treatment and demographic factors affecting time to next pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2015; 14: 763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanDevanter DR, Morris NJ, Konstan MW. IV-treated pulmonary exacerbations in the prior year: An important independent risk factor for future pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2016; 15: 372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lubovich S, Zaragoza S, Rodriguez V, Buendia J, Camargo Vargas B, Alchundia Moreira J, Galanternik L, Ratto P, Teper A. Risk factors associated with pulmonary exacerbations in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. Arch Argent Pediatr 2019; 117: e466–e472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brookhart M, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T Variable Selection for Propensity Score Models. American Journal of Epidemiology 2006; 163: 1149–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraemer HC. Events per person-time (incidence rate): a misleading statistic? Stat Med 2009; 28: 1028–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity analysis for m-estimates, tests, and confidence intervals in matched observational studies. Biometrics 2007; 63: 456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983; 70: 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 1991; 10: 585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psioda MA, Soukup M, Ibrahim JG. A practical Bayesian adaptive design incorporating data from historical controls. Statistics in Medicine 2018; 37: 4054–4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hobbs BP, Carlin BP, Sargent DJ. Adaptive adjustment of the randomization ratio using historical control data. Clin Trials 2013; 10: 430–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treggiari MM, Rosenfeld M, Mayer-Hamblett N, Retsch-Bogart G, Gibson RL, Williams J, Emerson J, Kronmal RA, Ramsey BW, Group ES. Early anti-pseudomonal acquisition in young patients with cystic fibrosis: rationale and design of the EPIC clinical trial and observational study'. Contemp Clin Trials 2009; 30: 256–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]