Abstract

Sleep and circadian rhythms disturbances (SCRD) in young people at high risk or with early onset of bipolar disorders (BD) are poorly understood. We systematically searched for studies of self, observer or objective estimates of SCRD in asymptomatic or symptomatic offspring of parents with BD (OSBD), individuals with presentations meeting recognized BD-at-risk criteria (BAR) and youth with recent onset of full-threshold BD (FT-BD). Of 76 studies eligible for systematic review, 35 (46%) were included in random effects meta-analyses. Pooled analyses of self-ratings related to circadian rhythms demonstrated greater preference for eveningness and more dysregulation of social rhythms in BAR and FT-BD groups; analyses of actigraphy provided some support for these findings. Meta-analysis of prospective studies showed that pre-existing SCRD were associated with a 40% increased risk of onset of BD, but heterogeneity in assessments was a significant concern. Overall, we identified longer total sleep time (Hedges g: 0.34; 95% confidence intervals: .1, .57), especially in OSBD and FT-BD and meta-regression analysis indicated the effect sizes was moderated by the proportion of any sample manifesting psychopathology or receiving psychotropic medications. This evolving field of research would benefit from greater attention to circadian rhythm as well as sleep quality measures.

Keywords: Bipolar disorders, children, youth, circadian rhythms, sleep quality, high risk, first episode, meta-regression

Introduction

Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances (SCRD) are common state characteristics of acute episodes of bipolar disorders (BD) (Harvey et al, 2009). Further, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of cross-sectional case-control studies demonstrate that self, observer or objectively assessed SCRD occur frequently in euthymia or inter-episode intervals (Geoffroy et al, 2015; De Crescenzo et al, 2017; Melo et al, 2017; Scott et al, 2017; Scott et al, 2020a). However, most publications focus on comparisons with healthy controls (HC) only and clinical studies of patients aged 40-50 with a long-standing diagnosis of BD (of 10-20 years) (Scott et al, 2017). As such, there is limited evidence about whether any SCRD show diagnostic specificity and/or the prevalence or nature of any SCRD that occur prior to the onset of full-threshold episodes of BD.

Few publications have synthesized evidence about SCRD in BD compared with other psychiatric diagnoses but, for example, reviews of BD versus psychotic or depressive disorders indicate that abnormalities are prevalent across these diagnoses and that SCRD may vary according to duration of illness or exposure to different classes of prescribed medications rather than diagnosis per se (Bellivier et al, 2013; Tazawa et al, 2019; Meyer et al, 2020). Investigating whether SCRD represent trait vulnerabilities is complex, but researchers have begun to examine SCRD in individuals perceived to be at high risk of developing BD such as the offspring of parents with BD (OSBD), youth with bipolar-at-risk states (BAR) and/or adolescent or young adults with recent onset of full-threshold BD (FT-BD) (Bechdolf et al, 2014; McGorry et al, 2014; Faedda et al, 2015). To date, reviews and meta-analyses about SCRD in these groups report inconsistent findings (Ritter et al, 2011; Ritter et al, 2012; Ng et al, 2015; Melo et al , 2016; Barton et al, 2018; Pancheri et al, 2019; Zangani et al, 2020). This may be partly explained by significant differences in search strategies, heterogeneity in eligibility criteria for study inclusion, and the selection of SCRD and/or psychopathology (Scott et al, 2021). For example, one review included generic descriptions of sleep problems but only included OSBD (Pancheri et al, 2019; Zangani et al, 2020), some examined trans-diagnostic dimensions of risk (Barton et al, 2018) whilst others included studies of children and adolescents deemed at risk of BD alongside studies of middle-aged or older adults with extended illness histories (Ritter et al, 2011; Ng et al, 2015). Like the publications on older adults with established BD, the reviews mostly focused on comparisons with HC and none considered confounding variables (SCRD may covary with e.g., age, sex, body mass index (BMI), or medication use).

In summary, a review of the extant literature demonstrates robust evidence for SCRD in older adults with treated BD and that these SCRD differentiate BD from HC, but not necessarily from other mental disorders (Meyer et al, 2020; Scott et al, 2021). However, uncertainties exist about whether any self, observer and objective ratings of SCRD-

are consistently found in children and youth at high risk of developing BD (i.e., OSBD or BAR groups);

differentiate adolescents or young adults with recent onset full-threshold BD (FT-BD) from individuals diagnosed with other mental disorders and/or from HC who are closely matched for age and sex and/or

have predictive validity for first onset of BD during the peak age range for onset.

This systematic review and meta-analysis build on previous research in three important ways. First, we synthesize available data from a wide range of sources including studies of offspring of parents with mental disorders, prospective community cohorts, clinical staging models, and adolescent and young adults attending early intervention in psychiatry and/or other outpatient and inpatient services. Second, our examination of SCRD extends from studies of the quality and quantity of sleep to markers of circadian dysrhythmia. Third, we include many recent publications (unavailable to previous reviews) and the study design incorporates meta-regression analysis to identify demographic, clinical or other characteristics that influence the magnitude of any observed SCRD.

Methods

The protocol was lodged with an international registry prior to commencing the project (PROSPERO: CRD42019131091) and the research adheres to the PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines.

In the online supplementary materials, Appendix 1 provides PRISMA checklist; Appendix 2 provides detailed descriptions of subgroups, eligibility criteria, search strategy, and analytic procedures (plus additional references); and Appendix 3 provides a PRISMA flowchart. To further assist readers, we provide a list of all the acronyms and associated full names used throughout the review in Box 1 (located at the end of the main text). In this section we summarize key elements of the methodology.

Box 1: Acronyms and abbreviations used in this review.

ANX: Anxiety disorder

ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

ASx: Asymptomatic

BAR: Bipolar-at-risk

BD: Bipolar disorders

BD-I or II: Bipolar disorder type I or type II

BMI: body mass index

BLPD: Borderline personality disorder

CIs: Confidence intervals

DLMO: Dim light melatonin onset

EEG: Electro-encephalogram

EMA: Ecological momentary assessment

ESM: Experience sampling method

ES: Effect size

FT-BD: Recent onset of Full-threshold BD episode(s)

GBI: General Behavioural Index

HC: Healthy controls

HPS: Hypomania Personality Scale

HR: High risk

IS: Interdaily stability

ISRCTN: International registry of clinical trials and studies (number)

IV: Intradaily variability

LR: Low risk

MDD: Major depressive disorder

MDQ: Mood Disorders Questionnaire

MEQ: Morningness Eveningness Questionnaire

MOOSE: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology

MR: Moderate risk

N/C: Number of studies/number of subgroup comparisons

OR: odds ratio

OS: Offspring

OSBD: Offspring of parents with BD

OSBD (+UP): Offspring of parents with bipolar and unipolar disorders

OSC: Offspring of controls

OSCwD: Offspring with depressive symptoms or syndromes

OSUP: Offspring of parents with unipolar disorders

PE: Parametric Effect

PRISMA: Preferred reporting for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

PROSPERO: Prospective register of systematic reviews

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

PSG: polysomnography

PSYCH: Psychotic disorder

RA: Relative amplitude

s.e.: standard error

SE: Sleep efficiency

SRM: Social Rhythm Metric

SOff: Sleep Offset

SOn: Sleep onset

SOL: Sleep onset latency

SCRD: Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances

TST: Total sleep time

WASO: Awakenings after sleep onset

Operationalization of key constructs

Prior to commencing the literature search, consensus definitions for subgroups according to the presence or absence of risk factors and/or psychopathology were agreed. We followed a template applied successfully in previous research which draws on clinical staging frameworks and includes age as an eligibility criterion (see Appendix 2) (McGorry et al, 2014; Vallerno et al, 2015). Our target populations comprised-

OSBD: where possible, we further sub-divided the OSBD population into asymptomatic OSBD or symptomatic OSBD (i.e., OSBD who report psychopathology, but whose mood symptoms are subthreshold for BD)

BAR groups: sub-threshold manifestations of BD assessed using an established instrument with known reliability and validity for identifying adolescents or young adults at risk of developing BD (Waugh et al, 2014)

FT-BD: presentations that met full-threshold diagnostic criteria for BD-I or BD-II with first onset by about 25 years (Vallarino et al, 2015)

We classified findings about SCRD according to the measurement employed and the phenomena assessed. Studies employing objective measures could include actigraphy (using wrist worn devices), polysomnography (PSG), dim light melatonin onset (DLMO), etc. Findings were subcategorized into estimates of circadian rhythmicity (CR) and sleep timing or estimates of sleep quantity and quality (see Appendix 2). Likewise, we recorded data from observer and self-ratings obtained using established instruments that provided continuous or categorical assessments of CR (such as chronotype or social rhythms) or continuous measures of sleep quality, quantity or routines (e.g., Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSQI). For the planned analysis of prospective cohort studies reporting new onsets of BD, we included any categorical assessment of SCRD included by the original researchers.

Eligibility

Criteria for inclusion in the narrative review were:

The study sample was wholly or partly comprised of individuals who met criteria for OSBD, BAR, and/or FT-BD

If the study included FT-BD cases, the mean or median age at onset of BD was within the peak age range for onset (15-25 years) and the overall age range for the total sample was 12-30 years (Vallarino et al, 2015)

The study specified the range and type of psychopathology assessments employed.

The study specified how SCRD were estimated; reported baseline rates for at least one; and compared SCRD between cases and controls or examined the association between SCRD and future onset of BD.

If the study included a prospective follow-up phase, it clearly reported the chronological sequence of assessments.

The key exclusion criteria were:

Studies in samples recruited because they had a specific physical disorder or recruited from general medical settings.

Studies where SCRD assessments exclusively focused on parasomnias or single item ratings of nightmares, sleep apnea or sleep paralysis, etc.

Studies where SCRD assessments were restricted only to infants and toddlers (age<4) without reports of further assessments (during childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood)

Studies of full-threshold BD in pre-pubertal or young children (age=<11) only (Vallarino et al, 2015)

Retrospective studies of prodromal symptoms preceding first BD episodes or relapses (Faedda et al, 2015)

Additional criteria for the meta-analysis were-

The study should report >=1 recognized measure of the magnitude of the association between SCRD metrics and (a) cases that were or could be categorized as OSBD, BAR or FT-BD or (b) between cases and comparator groups (e.g. adjusted or unadjusted odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio, or relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)) or (c) estimates could be made by our investigators.

Publications that included only a subsample of participants in the pre-determined age range could be included in the meta-analysis if specific data about SCRD for the pre-determined age ranges and eligible subgroups could be extracted.

Studies that reported repeated follow-ups (waves) were included from the meta-analysis if it was possible to examine risk of BD at each follow-up or identify summary outcomes at final follow-up. If this was unclear data from the most recent publication only was included in the pooled analyses.

More than one study about the same cohort/sample could be included if it was established that the publications reported (a) different subsamples or (b) different SCRD or psychopathology outcomes for the original sample, and/or (c) a follow-up of a cross-sectional study that provided new data regarding associations between SCRD and longitudinal outcomes.

Search Strategy and Data Management

We did not set a lower limit for date of publication, but the end date was December 31st, 2021. Articles reporting original research findings from cross-sectional, case-control, clinical trial (if relevant baseline data were reported), cohort, longitudinal and prospective follow-up studies in community, epidemiological or clinical samples published in English, French, Italian, Spanish, or German were eligible.

Search strategies were devised using relevant subject headings for each of the following databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase, Web of Science (which also incorporates searches of Medline, SciELO and KLI-Korean journal databases), and Dissertation Abstracts. Alerts were set up for all databases to ensure ‘in press’ or early view’ articles were identified and could be assessed for eligibility in a timely manner (up to the date of finalizing the manuscript for submission). All search terms are provided in Appendix 2. Data searches were initially conducted by two investigators (JS, BE). Also, we hand-searched reference lists, checked specific journals and contacted researchers in the field about ongoing or recently completed studies.

Titles and abstracts of all papers identified by the searches were screened, duplicates removed, abstracts examined, and full copies of manuscripts for all potentially relevant studies were obtained and reviewed according to the pre-specified criteria. Uncertainties regarding eligibility were resolved by expert consensus.

Quality Assessment

Quality of included studies was assessed independently by two raters (random pairings of investigators) using the 14-item Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (available at http://nhlbi.nih.gov). For each publication, raters agreed a total score (out of 14) and a quality grading (5 categories ranging from good to poor).

Synthesis and statistical analysis

A qualitative review was undertaken to summarize findings from all included studies followed by quantitative analyses of pooled data from the subset eligible for meta-analysis (see Appendix 2). For the latter, a key criterion was that any variable of interest should be reported in >=3 studies (or 2 studies reporting >=3 relevant subgroup comparisons) about OSBD or BAR or FT-BD groups.

The Comprehensive Meta-Analysis programme (version 3) was used to estimate pooled effect sizes (ES) which are reported as Hedges g and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for analyses continuous data and odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI for categorical data. Forest plots are based on random-effects models and a positive ES infers higher values in the pre-defined subgroups relative to comparators. Heterogeneity is reported using the I2 index (an I2=50% is indicative of moderate heterogeneity). We used funnel plots and Egger’s test to explore risk of publication bias (data permitting) and report the Fail-Safe Number (FSN; which is the number of additional hypothetical studies with zero effect that would make the summary effect in any meta-analysis trivial, defined as Hedges g<0.10). As noted in Appendix 2, we employed meta-regression to explore whether any characteristics of study design significantly affected the magnitude of an effect. We plotted log ES versus each variable to examine confounding associated with the mean age at study entry, sex distribution, the proportion of the sample that were asymptomatic and the proportion of each study sample prescribed psychotropics. These planned analyses were subject to number of eligible studies available that provided relevant data (subject to a minimum of 10 studies being available and an I2 indicating moderate-to-high heterogeneity). The selection of potential confounders was based on the scientific rationale for examining key variables, but some potentially relevant variables (e.g., alcohol and substance misuse) could not be examined because information was not included in the original investigations.

Results

We identified a total of 4353 records; 1309 were suitable for screening (after de-duplication). As shown in the PRISMA flow chart (Appendix 3), evaluation of 165 full text records identified 76 publications that met eligibility criteria for the review, 35 of which were suitable for the planned meta-analyses. The studies are described in detail in supplementary Tables 1S–5S (Appendix 4).

Systematic review

Table 1 summarizes details of the 76 studies included in the systematic review (these citations are provided in Appendix 4). Together these studies included >21,000 observations or recordings of SWRCD. Articles were published by 45 independent research groups over 30 years (1992-2021). The review indicated that SCRD were nearly always more prevalent in OSBD, BAR and FT-BD versus HC, but no other specific patterns were discerned in the narrative.

Table 1:

Overview of studies eligible for systematic review & pooled analyses (full details of each study are reported in supplementary Tables 1S–5S in Appendix 4).

| OSBDa | Bipolar-At-Risk populationsb | Cross-sectional studies: BAR vs other groups | Cohort studies: Transition to Full-Threshold BD | Cross-sectional studies: Full-Threshold BD vs. other groupsc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of: | |||||

| Studies Eligible for Systematic Reviewd | 21 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 21 |

| Independent Research Groups | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 11 |

| Location of Research Groups: | |||||

| USA/Canada | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Europe | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| South America/Asia/Other | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Sample Characteristics: | |||||

| Total Number of Participants | 1866 | 4426 | 1471 | 10177 | 3426 |

| Median sample size (Range) | 81 (14-687) | 163 (40-1440) | 115 (44-734) | 233 (28-2767) | 89 (49-1023) |

| Median age at recruitment in years | ~15 | ~19 | ~20 | ~19 | ~22 |

| Median % females | 52% | 60% | 53% | 59% | 55% |

| SCRD Measures e : | |||||

| Sleep items selected from investigator-designed or psychopathology scales | 5 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Self- or Observer ratings of established scales (e.g. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) | 6 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Actigraphy | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Other objective assessments (e.g. melatonin secretion, polysomnography, etc) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Median Quality Rating (with Interquartile Range) | 9 (6-11) | 7 (3-10) | 7 (4-10) | 10 (7-12) | 7 (4-9) |

| Meta-analysis of SCRD e : | |||||

| Number of Eligible Studies | 13 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 8 |

| Studies including Objective Measures | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Studies including Self &/or Observer Measures f | 11 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

Some OSBD studies included prospective follow-up allowing analysis of transition to full-threshold episode of BD;

This category refers to studies of Non-OSBD samples who were defined as being at high risk of Bd according to recognised criteria for a BAR syndrome (see text for details);

Comparators include HC &/or other diagnoses;

Some independent research groups published >1 article related to SCRD in the same sample, so the SCRD measures are reported according to independent research group;

The number of measures may exceed the number of independent research groups as some employed >1 method of assessment;

Several studies used both self- and observer-ratings, so we have not further sub-divided the data here (see Appendix 4 for details)

Similar numbers of research groups were located in North America (n=17) or Europe (n=16), but the focus of studies differed. For example, 60% of independent groups investigating OSBD were located in North America, whereas 70% of independent groups researching BAR populations were located in Europe. The median age of study samples ranged from about 15 years (OSBD studies) up to about 22 years (recent onset BD). The median proportion of females (55%) was similar across all types of study (see Table 1). About 80% of case-control studies reported that subgroups were matched or closely matched for age and sex. Median sample sizes differed according to study design, with cross-sectional studies including about 80-100 participants and most cohort studies including more than twice that number. It was noteworthy that whilst many OSBD studies comprised smaller samples they were more likely to report separate univariate analyses for several OSBD subgroups, and/or different combinations of observer and objective measures of sleep metrics (e.g., comparing subgroups of asymptomatic or symptomatic OSBD with offspring of controls (OSC)).

Quality assessment ratings identified that the median scores were similar for cohort (median 10) and OSBD studies (median 9), but lower for all other study designs, with median scores (about 7) in the fair or fair-to-poor range (see Table 1). Assessors noted that a typical weakness of larger studies was the reliance on simple assessments of SCRD (often a single item and/or a broad-based question about sleep difficulties), whilst typical weaknesses of cross-sectional studies were small sample size, multiple comparisons of selected SCRD variables across a range of subgroups and lack of consideration of statistical power.

Meta-analyses

Of 76 studies included in the systematic review, 35 (46%) were eligible for >=1 pooled analysis (each citation is identified by an asterix in the Reference list). Quality assessment ratings indicated that 20 of the 35 studies were graded as good or fair quality (see Appendix 5). As shown in Table 2, 13 studies reported ratings of established SCRD scales (e.g., PSQI), 13 reported data for >=1 actigraphy metric (see Appendix 2 for definitions), whilst the remainder used various combinations of ratings (including investigator-designed assessments). Although the number of SCRD data items totalled about 13000, about 61% of these were extracted from 7 prospective cohort studies (included in the pooled analysis of new onsets of BD).

Table 2:

Summary of the key information regarding cross-sectional studies included in the meta-analyses (for citations see Table 6S in Appendix 4)

| Measures of SCRD | N studies/N subgroup comparisons | OSBD, BAR & Recent Onset BD | Comparators | Meta-analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % Sx/Dx | % Meds | N | % Sx/Dx | % Meds | I2 | FSN | ||

| Self-Rated | |||||||||

| MEQ (continuous) | 6/6 | 822 | 41% | 32% | 1303 | 26% | 21% | 18% | 17 |

| SRM (continuous) | 4 / 5 | 393 | 34% | - | 467 | 21% | - | 15% | 21 |

| MEQ (categories) | 6 / 9 | 638 | 53% | 47% | 847 | 45% | 40% | 36% | 4 |

| Observer-Rated | |||||||||

| Sleep Quality (continuous measures: PSQI; CHSQ; SSHS) | 4/6 | 276 | 63% | - | 254 | 38% | - | 41% | 44 |

| Prospective cohort studies employing investigator defined SCRD (categories) | 7 | 5306 | 62% | 59% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 55% | 40 |

| Actigraphy | |||||||||

| TST | 11 / 20 | 393 | 54% | 45% | 278 | 32% | 27% | 61% | 6 |

| SOL | 9 / 16 | 301 | 51% | 34% | 216 | 32% | 24% | 68% | 29 |

| WASO | 6 / 16 | 236 | 44% | 32% | 141 | 36% | 25% | 80% | 92 |

| SE | 10/ 17 | 292 | 42% | 40% | 227 | 31% | 29% | 56% | 3 |

| SOn | 6 / 14 | 193 | 47% | - | 528 | 44% | - | 10% | 9 |

| SOff | 6 / 14 | 193 | 47% | - | 528 | 44% | - | 29% | 15 |

| IS | 4 / 4 | 106 | (10%) | - | 101 | (0%) | - | 10% | 6 |

| IV | 4 / 4 | 106 | (10%) | - | 101 | (0%) | - | 32% | 5 |

| RA | 3 / 3 | 86 | (10%) | - | 80 | (0%) | - | 5% | 7 |

NB: any % shown in parentheses indicates the estimate should be treated with caution; a dash (-) denotes that there was insufficient data to make a reliable estimate. N/A: not applicable (NB- cohorts comprised individuals with varying levels of risk of developing BD and different proportions of each cohort became new full-threshold BD cases.)

% Sx/Dx: % of participants who were symptomatic &/or had a diagnosis of a mental disorder; % Meds: % of participants known to be prescribed psychotropic medications.

I2: heterogeneity index FSN: Fail Safe Number;

BD: Bipolar disorder; HC: CHSQ: CSHQ: Children’s sleep habit questionnaire; Healthy Control; IS: Interdaily stability; IV: Intradaily variability; MEQ: Morningness-eveningness questionnaire; N: number; PSQI: Pittsburgh sleep quality index; RA: relative amplitude; SE: Sleep efficiency; SOff: Sleep offset; SOn: Sleep onset; SOL: Sleep onset latency; SRM: Social rhythm metric; SSHQ: School sleep habits survey; WASO: Awakenings after sleep onset; TST: Total sleep time.

Table 2 summarizes details related to the random effects meta-analyses of different SCRD (no pooled analyses were possible PSG, for EEG or DLMO) and highlights the number of studies and comparisons included in each pooled analysis (also, see Table 6S in Appendix 4). As shown, the I2 indices suggest that most analyses showed moderate levels of heterogeneity with higher levels for actigraphy variables such TST (I2=61%), SOL (I2=68%) and WASO (I2=80%).

Below we report the main findings and Forest plots (Figures 1–3). Other outputs and funnel plots are included in the Appendices 6 and 7 (or are available from the authors).

Figure 1:

Pooled analyses of actigraphy metrics in OSBD or BAR groups versus comparators (see text for details)

a) Eligible OSBD studies

b) Eligible BAR studies

*Citations for studies included in pooled analyses are provided in the main text.

S/C: Numbers of Studies/Comparisons included in pooled analysis; OS: Offspring; BAR: Bipolar at Risk; BD: Bipolar Disorders; HC: Healthy Controls;

RA: Relative Amplitude; IS: Interdaily stability; IV: Intradaily variability; SE: Sleep efficiency; SOL: Sleep onset latency; SOn: Sleep onset; SOff: Sleep offset;

TST: Total sleep time

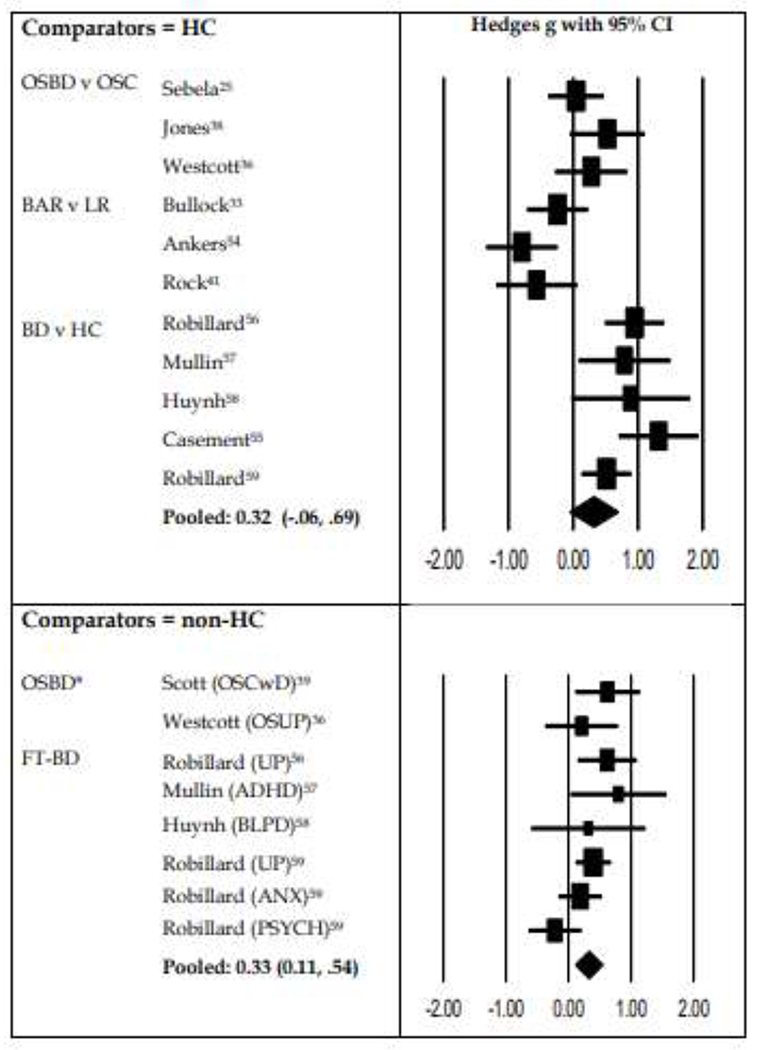

Figure 3:

Pooled analyses of studies of Total Sleep Time (TST) categorized according to comparisons with Healthy Controls (individuals with minimal or no symptoms) or individuals with psychiatric symptoms or disorders (non-HC)

ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ANX: Anxiety disorder; BAR: Bipolar at risk group; BD: Bipolar disorder; BLPD: Borderline personality disorder; FT: Full-threshold; HC: Healthy controls; LR: Low Risk (as assessed with BAR instrument); OSBD: Offspring of parent with Bipolar Disorder; OSC: Offspring of healthy controls; OSCwD: OSC who have depression; OSUP: Offspring of parents with UP; PSYCH: psychosis ;UP: Unipolar depression.

Self and observer ratings

Cross-sectional studies: Pooled analyses were possible for 4 OSBD studies of observer ratings of continuous measures of sleep quality or quantity (PSQI, CCHQ, and SSHS) (Westcott et al, 2019; Soehner et al, 2016; Jones et al, 2006; Scott et al, 2020b); 4 BAR studies of self-ratings of the SRM (Meyer T et al, 2006; Bullock et al, 2011; Bullock et al, 2014; Alloy et al, 2017; Shen G et al, 2008) and 4 FT-BD studies of self-ratings of the MEQ (Levenson et al, 2017; Faria et al, 2015; Mondin et al, 2017; Robillard et al, 2013). As shown in supplementary Figure 1S (in Appendix 6), we found that OSBD had significantly worse sleep quality compared with OSC (Hedges g: .68; 95% CI: .32, 1.04); BAR groups showed significantly lower social rhythmicity (Hedges g: −.34; 95% CI: −.16, −.51); and FT-BD showed higher continuous scores on the MEQ (indicating higher levels of eveningness) than comparators (Hedges g: .45; 95% CI: 0.12, 0.71). The 4 FT-BD studies of MEQ categories confirmed greater eveningness in BD cases (OR: 1.87; 95% CI: 1.29, 2.41).

Prospective studies: Data from 7 studies (including 7892 participants) were eligible for the meta-analysis of transition to BD caseness (Alloy et al, 2015; Iorfino et al, 2019; Levenson et al, 2017; Mesmen et al, 2017) Pfennig et al, 2016; Ritter et al, 2015; Scott et al, 2020b). Samples and measures were heterogenous: 2 studies evaluated OSBD, 2 evaluated BAR, 2 reported prospective assessment of SCRD and later onset of BD and one examined transition from depression to BD in young people with or without SCRD. As shown in Figure 2S (Appendix 6), the OR was 1.41 (95% CI: 1.11, 1.78) for future onset of BD in individuals with SCRD compared to those without.

Actigraphy

There were sufficient studies to undertake pooled analyses of mean values for 4 sleep quality or quantity metrics (TST, SOL, SE, and/or WASO) and 5 circadian rhythmicity metrics (SOn, SOff, IS, IV, RA) for at least one subgroup.

Figure 1 shows pooled analyses of actigraphy data for OSBD (1a) and BAR (1b) groups (and provides the citations). As shown in Figure 1a, two actigraphy estimates differentiate OSBD from comparator groups: longer TST (g .27; 95% CI: .11, .53 ) and later clock time for SOff (g .61; 95% CI: .2, 1.02) (Sebela et al, 2019; Westcott et al, 2019; Jones et al, 2006; Scott et al, 2016).

Figure 1b suggests that compared with low risk groups (usually HC), those meeting BAR criteria have a shorter sleep duration (g for TST.−.54; 95% CI: −.17, −.84) and demonstrate lower stability (g for IS: −.42), greater variability (g for IV: .39) and lower amplitude (g for RA: −.57) in their circadian rhythms (Castro et al, 2015; Bullock et al, 2014; Rock et al, 2014; Ankers and Jones, 2009).

As shown in Figure 2, more studies were available that compared FT-BD with HC and/or other disorders (Robillard et al, 2013; Robillard et al, 2015; Robillard et al, 2016; Casement et al, 2019; Mullin et al, 2011; Huynh et al, 2016); The key finding was the effect for TST (FT-BD versus all comparators; g: .32; 95% CI: −.06, .69) and the separate estimates of Hedges g fir FT-BD versus HC (g: .84; 95% CI: .54, 1.14) or versus other disorders (g: .30; 95% CI: .03, .57) (Robillard et al, 2013; Robillard et al, 2016; Casement et al, 2019; Mullin et al, 2011; Huynh et al, 2016). Findings were mixed for other measures of sleep quality and quantity such as SOL (longer in FT-BD than HC; g .92) (Robillard et al, 2015; Robillard 2016; Mullin et al, 2011; Huynh et al, 2016) and SE (higher in FT-BD than other disorders; g .34). (Robillard et al, 2013; Robillard 2016; Mullin et al, 2011; Huynh et al, 2016). Findings for circadian rhythm disturbances demonstrated later SOn (g: .49; 95% CI: .21.77) and SOff (g: 1.07; 95% CI: .78, 1.36) in FT-BD compared with HC but not FT-BD versus young people with other disorders (Robillard et al, 2015; Robillard 2016; Mullin et al, 2011; Huynh et al, 2016).

Figure 2:

Pooled analyses of actigraphy metrics in OSBD or BAR groups versus comparators (see text for details)

*Citations for studies included in pooled analyses are provided in the main text.

S/C: Numbers of Studies/Comparisons included in pooled analysis; BD: Bipolar Disorders; HC: Healthy Controls; SE: Sleep efficiency; SOL: Sleep onset latency; SOn: Sleep onset; SOff: Sleep offset; TST: Total sleep time; WASO: Awakening after sleep onset.

Subgroup and Meta-regression analyses

A subgroup analysis was possible for cross-sectional studies that estimated mean TST only (see Table 6S for list of studies). As shown in Figure 3, the subgroup analysis compares individuals who were symptomatic with those who were asymptomatic. The top section of Figure 3 (which focuses on comparator groups that were asymptomatic) shows the pooled effect size for TST for OSBD, BAR and FT-BD groups versus HC (g: .32; 95% CI: −.06, .69). The bottom section of Figure 3 shows the pooled analysis for studies that included symptomatic comparator groups (g: .33; 95% CI: .11, .54).

Studies of two actigraphy variables met criteria for meta-regression analysis- mean TST and sleep efficiency. Meta-regression analysis demonstrated an association between the effect size for TST and older age at study entry (Parameter Estimate [PE]=0.3; s.e.=0.056, Z=3.71; p<0.001), a smaller proportion of study participants who were asymptomatic (PE=−.13; s.e.=0.05; Z=−2.59; p<0.01) and a larger proportion of study participants being prescribed medication (PE=0.47; s.e.=0.18; Z=4.71; p<0.001).

Meta-regression analysis was possible also for sleep efficiency (see Table 6S for list of studies). This demonstrated that a larger proportion of study participants being prescribed medication (PE=0.26; s.e.=0.08; Z=3.34; p<0.01) was associated with a greater effect on sleep efficiency (older age showed a similar trend; p=0.06).

Discussion

The significant morbidity and mortality among young people with BD have encouraged discussions about preventing the onset of full-threshold episodes or delaying relapses (Conus et al, 2014; McUntyre et al, 2020). However, a rate limiting step for early interventions is the identification of appropriate modifiable risk factors (Kioumourtzoglo, 2019). Recent publications have highlighted the notion that sleep regulation might represent a suitable target for individuals at risk of or with recent onset of BD (Scott et al, 2020; Crouse et al, 2020). However, before advocating for the introduction of any more specific interventions, it is necessary to clarify what is known about the magnitude and/or specificity of any SCRD problems in populations with different early expressions of BD (i.e., OSBD, BAR, FT-BD). Also, findings from this meta-analysis need to be considered in the context of potential confounding factors in the studies reviewed and areas of agreement between the findings reported here and other important studies that did not meet eligibility for inclusion (Faedda et al, 2016; Hensch et al, 2019; Shou et al, 2017).

The Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that SCRD are common in individuals with different early expressions of BD. For example, we found moderate to large ES for self or observer ratings of continuous measures of SCRD, although group comparisons were hampered by different measurement strategies (e.g. the use of observer ratings of quality in OSBD but self-ratings of circadian rhythms in BAR and FT-BD). Overall, there was evidence that disturbances in sleep quality increased as symptom load increased, but the different measures used mean we cannot delve further into the exact nature of problems. There was more convincing evidence for differences regarding chronotype (MEQ ratings) and social rhythms (SRM ratings) with the pooled analyses indicating greater preference for eveningness and more dysregulated rhythms in BAR and FT-BD groups versus other comparators.

Our meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies (which used a mixture of self- and observer ratings) found that individuals with self- or observer rated SCRD had a 40% increased risk of onset of BD during repeated cross-sectional follow-ups. Whilst the magnitude of the increase in BD onsets suggests this is an important area for further research, we highlight that we were unable to examine if SCRD that are specifically hypothesized to be linked to BD (e.g., hypersomnia, non-restorative sleep, decreased daytime physical activity, day-to-day variability in 24-hour sleeps) were associated with full-threshold episode onset. Also, the lack of intensive longitudinal monitoring meant it was not possible to map the evolution of reported SCRD over Lime nor evaluate their association with other antecedent conditions (such as anxiety or depression) (Duffy et al, 2019).

Only studies using actigraphy were eligible for the meta-analyses of objective measures of SCRD. Regarding sleep quality/quantity, estimates of ES were inconclusive for mean values of SOL, WASO and SE (although ES for SOL showed a similar pattern to those for TST), but we found evidence for longer TST (albeit with the opposite finding in analyses of BAR groups alone). Our findings contrast with meta-analyses of studies of older adults with long-established BD cases that often receive polypharmacy which demonstrate moderate to large ES for TST, SOL, WASO, and SE (Geoffroy et al, 2015; Meyer et al, 2020). Currently, we cannot determine whether the differences in findings are best understood from the perspective of heterogeneity in research methodologies, age-related sleep patterns, or illness- and lifestyle-related factors. However, our TST findings are worthy of further comment, especially as we were able to consider also the potential moderators and sources of confounding.

When all groups are considered together, findings for TST indicated that sleep duration was longer than in comparator groups. This was primarily due to the ES for TST associated with OSBD and FT-BD. The findings are compatible with other recent studies of sleep and rest-activity patterns (Hensch et al, 2019; Shou et al, 2017; Kolla et al, 2019) and may reflect a lack of quality of ‘restorative’ sleep and a reduction in slow wave sleep (Mander et al, 2017; Ohayon et al, 2004). However, the ES for TST across all groups contrasts with the pooled analysis of BAR groups alone. The observed reduction in TST in the latter is more typical of sleep disturbances such as insomnia, particularly those linked with common mental disorders such as anxiety (Alvaro et al, 2013). It is possible that individuals identified using BAR criteria (which often screen for hypomanic symptoms in populations with other trans-diagnostic symptoms) have different BD risk profiles or perhaps that their symptoms are more typical of early adolescence (compared with OSBD studies that often focus on asymptomatic children) (Bechdolf et al, 2014). In FT-BD groups, we found that the ES is attenuated when TST is compared with other disorders, and it may be that sleep duration in BD is longer than some (such as unipolar depression and BLPD) but not all other disorders (e.g., psychosis). The TST findings may be associated with age, symptom levels or illness progression. Of those factors we could explore in a meta-regression we found that the magnitude of ES for TST are influenced by the prevalence of psychopathology in study samples (including psychiatric symptoms or diagnoses), but also by the use of psychotropic medications. These findings are in keeping with previous research and a recent meta-analysis of BD and psychosis, with the latter particularly highlighting the role of medications such as atypical antipsychotics in prolonging TST (Meyer et al, 2020; Robillard et al, 2015; Wang et al, 2014).

We found small-to-moderate ES for proxies of circadian rhythmicity, all of which indicated greater disturbance in the early expressions of BD (OSBD, BAR and FT-BD groups) compared with other populations. For example, OSBD showed later sleep offset compared with other populations, and this finding was replicated when FT-BD were compared with HC (sleep onset was later also in the FT-BD versus HC). Likewise, BAR groups demonstrated disturbances in stability (IS), variability (IV), and relative amplitude (RA) of circadian rhythms. Although relatively few studies were eligible for these pooled analyses and many of these comprised small samples, there appears to be consistency across objective recordings and self- or observer ratings. (e.g., Tonetti et al, 2015; Urbanek et al, 2018). For example, delayed sleep onset and offset is compatible with eveningness chronotype and IS, IV and RA disturbances may be associated with dysregulated social rhythms. Whilst it can be argued that these features are often described in adolescents and young adults, they were more pronounced in individuals with early expression of BD (even without symptoms) compared to other populations of similar age. As such, these findings offer tentative support for views that circadian dysrhythmias may play a causal role in the evolution of BD and/or act as important triggers of mood episodes (McClung, 2013; Takaesu, 2018). The findings we report are also consistent with a physiological temporal change in chronotype and sleep duration from childhood into adolescence but suggest both an earlier occurrence and an amplification of this natural process in individuals transitioning through the early expressions of BD (Mander et al, 2017; Mansour et al, 2005). The circadian findings (instability and delays) may speak to a biological abnormality (SCN function, melatonin rhythm, light sensitivity) which should be explored further to guide interventions. As both behavioural and pharmacological interventions that target day-to-day stability of the circadian cycle are available, this finding may be of specific relevance in preventing the onset of syndromal BD in high-risk youth.

Limitations

Some limitations have been highlighted in the context of the findings, but other issues deserve mention. For example, many of the 76 studies included in the systematic review were not designed to examine SCRD only in specific subgroups at risk of BD and/or within a peak age range for onset of BD. This partly explains the relatively small proportion of publications judged to be of the highest quality. However, we identified other weaknesses in the 35 studies included in the meta-analysis. Notably, about 70% of the SCRD ratings were extracted from 20% of the eligible studies. Many cross-sectional studies, including, those with a stated focused on SCRD in OSBD or BAR groups, recruited small convenience samples, included (or reported) only selective measures, did not report potential moderators or sources of bias, and were frequently underpowered for multiple subgroup comparisons. To overcome some of these issues, we employed within study meta-analysis prior to the main analyses. However, the heterogeneity indices and the ‘fail safe numbers’ suggest that additional studies are required to improve confidence in the findings. Likewise, our ability to explore moderators and confounding was limited. Nearly all studies failed to provide detailed information about one of more of the following: symptom severity, BMI, education or employment participation (and daily routines), comorbidities, or use of medications, etc. Also, our estimates of the proportion of any sample reporting different types of psychopathology or receiving psychotropics must be viewed with caution, as we cannot be confident about the overall accuracy of these data across studies.

Implications for future research

Several methodological considerations may strengthen this area of research in the future. For example, this systematic review and meta-analysis highlights the need for careful consideration of how to evaluate SCRD in individuals at high risk of developing BD and how to include consideration of other variables that will influence any findings. There was an impression that the inclusion of measures of SCRD was opportunistic in some studies rather than a carefully planned or hypothesis-driven strategy. For example, it is known that alcohol and substance misuse may impact on sleep and circadian rhythmicity in youth, but also that such misuse is more common of clinical presentations of sub-threshold and full-threshold BD (Fernando et al, 2022). It is recommended that investigators consider which SCRD elements they are examining and also record concurrent problems and comorbidities (Leopold et al, 2012). As such, a long-term aspiration for future research is that investigators might be encouraged to develop a consensus on which SCRD should be prioritized and how these can best be measured in different age or risk groups.

In many OSBD and cohort studies, SCRD were often one of several aspects of psychopathology that are assessed. Whilst previous research has included insomnia or some elements of sleep quality, little attention has been devoted to hypersomnia, non-restorative sleep, daytime fatigue, circadian dysrhythmias or rest-activity patterns over 24-hours. Many of these issues are found in atypical depression (which in turn may be associated with greater risk of developing BD) (Scott et al, 2017), but few eligible studies recorded these patterns. As such, investigators need to consider how to capture efficiently a broader set of SCRD, or to present a more coherent rationale for the preferred items included in future studies.

Future research needs to consider how best to ‘mix and match’ subjective and objective ratings. For example, some recent research indicates that it may be possible to use chronotype questionnaires as an alternative to objective recordings (Thun et al, 2012). However, other evidence suggests significant discrepancies in self-perceived sleep patterns and objective recordings and indications that these discrepancies are amplified in BD cases compared with HC (Kaufmann et al, 2019). Investigators also need to consider which objective sleep quality/quantity variables are selected for recording and how these will be reported. For example, it would be useful to consider intra-individual variability in actigraphy metrics not just the mean values over time, as the former appears a more sensitive marker of future course of illness (Baddam et al, 2018; Bei et al, 2016).

Conclusions

Overall, we suggest that circadian rhythm disturbances may be more consistently associated with early expression of BD (in terms of risk and recent onset) than other measures of sleep quality or quantity. We emphasize that the quality of the available data and the exploratory nature of our meta-analyses and meta-regressions do not indicate causality and that further detailed research is required. If the findings are confirmed, this has implications for the types of interventions that might be planned. However, the key message for this project is that high-quality data-driven research about SCRD and early expression of BD is an evolving field and further work is needed to understand SCRD associated with different levels of risk (asymptomatic versus symptomatic OSBD; FT-BD versus other disorders rather than HC) and to clarify BAR criteria. Also, there is need for greater consensus on which actigraphy metrics might be examined, with more research required on circadian markers and variability rather than mean values of sleep quality markers. Lastly, the research field would benefit from increasing use of prospective longitudinal follow-ups including use of commercial devices for ecological monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Previous reviews and meta-analyses of sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances (SCRD) in bipolar disorders (BD) have primarily compared older adults with BD to healthy controls. As such, SCRD) in young people at high risk of or with recent onset of BD are poorly understood.

We categorized early expression of BD into three groups: those at risk of BD due to familial loading (OSBD), those who met established criteria for a Bipolar-at-Risk category (BAR are defined in similar ways to UHR for psychosis) and those who presented with a first episode of mania or hypomania during the peak age range for onset of BD (FT-BD).

A systematic search of the literature identified 76 relevant publications of which 35 provided data that could be included in random effects meta-analyses.

Observer ratings of sleep quality differentiated OSBD from comparison populations.

Bipolar-at-Risk and FT-BD populations reported greater preference for eveningness and more dysregulation of social rhythms, and meta-analyses of actigraphy data also indicated evidence of circadian dysrhythmias (e.g., delayed sleep offset).

Pooled analyses of all eligible actigraphy studies demonstrated longer total sleep time (Hedges g: 0.34; 95% CI: .1, .57), especially in OSBD and FT-BD. Meta-regression analysis indicated effect sizes for total sleep time were moderated by the proportion of any sample manifesting psychopathology or receiving psychotropic medications.

Comparisons with young people with other (non-BD) psychopathology such as depression, anxiety or psychotic syndromes suggested few SCRD that were uniquely associated with early expressions of BD. and

Acknowledgements:

Drs Crouse is supported in part by a Breakthrough Mental Health Research Foundation Fellowship and Dr Carpenter is supported in part by the Caroline Quinn Research Grant.

Prof Merikangas was supported in part by grant Z-01-MH002804 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Intramural Research Program. She leads an international consortium called mMARCH (investigating rest-activity rhythms in mental disorders). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US Government.

Professor Ian Hickie was a Commissioner in Australia’s National Mental Health Commission from 2012-2018. He is the Co-Director, Health and Policy at the Brain and Mind Centre (BMC) University of Sydney. Professor Hickie has previously led community-based and pharmaceutical industry-supported (Wyeth, Eh Lily, Servier, Pfizer, AstraZeneca) projects focused on the identification and better management of anxiety and depression. He has led investigator-initiated studies supported by Servier, the manufacturer of agomelatine. He is the Chief Scientific Advisor to, and an equity shareholder in, InnoWell (formed by the University of Sydney and PwC).

Funding-

This research project did not receive any funding from grant giving agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest-

Professors Scott, Etain, Miklowitz, Smith and Marwaha, plus Drs Crouse and Carpenter declare no conflicts in respect to the submitted manuscript.

Data Statement-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created. The summary data that were reviewed and/or included in pooled analyses are detailed in the supplementary materials and findings reported in the manuscript. Other summary statistics and outputs are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References-

*Indicates articles that contributed data included in the meta-analysis

- *Alloy LB, Boland EM, Ng TH, Whitehouse WG, Abramson LY. 2015. Low social rhythm regularity predicts first onset of bipolar spectrum disorders among at-risk individuals with reward hypersensitivity. J Abnorm Psychol. Nov;124(4):944–952. doi: 10.1037/abn0000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvaro P, Roberts R, Harris J. 2013. A Systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. Jul 1;36(7):1059e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ankers D, Jones SH. 2009. Objective assessment of circadian activity and sleep patterns in individuals at behavioural risk of hypomania. J Clin Psychol. Oct;65(10):1071–86. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddam SKR, Canapari CA, van Noordt SJR, Crowley MJ. 2018. Sleep disturbances in child and adolescent mental health disorders: A review of the variability of objective sleep markers. Med Sci (Basel). Jun 4;6(2):46. doi: 10.3390/medsci6020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton J, Kyle SD, Varese F, Jones SH, Haddock G. 2018. Are sleep disturbances causally linked to the presence and severity of psychotic-like, dissociative and hypomanic experiences in non-clinical populations? A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. Jun;89:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechdolf A, Ratheesh A, Cotton S, Nelson B, Chanen A, Betts J, et al. 2014. The predictive validity of bipolar at-risk (prodromal) criteria in help-seeking adolescents and young adults: a prospective study. Bipolar Disord. Aug;16(5):493–504. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellivier F, Geoffroy PA, Scott J, Schurhoff F, Leboyer M, Etain B. Biomarkers of bipolar disorder: specific or shared with schizophrenia? Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2013. Jun 1;5:845–63. doi: 10.2741/e665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei B, Wiley JF, Trinder J, Manber R. 2016. Beyond the mean: A systematic review on the correlates of daily intraindividual variability of sleep/wake patterns. Sleep Med Rev. Aug;28:108–24. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Monk K, Kalas C, Obreja M, et al. 2010. Psychiatric disorders in preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS). Am J Psychiatry. Mar;167(3):321–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bullock B, Judd F, Murray G. 2011. Social rhythms and vulnerability to bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. Dec;135(1-3):384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bullock B, Corlass-Brown J, Murray G. 2014. Eveningness and Seasonality are Associated with the Bipolar Disorder Vulnerability Trait. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 36, 443–451. 10.1007/s10862-014-9414-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Bullock B, Murray G. 2014. Reduced Amplitude of the 24-hour Activity Rhythm: A Biomarker of Vulnerability to Bipolar Disorder? Clinical Psychological Science. 2(1):86–96. doi: 10.1177/2167702613490158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Casement MD, Goldstein TR, Merranko J, Gratzmiller SM, Franzen PL. 2019. Sleep and parasympathetic activity during rest and stress in healthy adolescents and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. Nov/Dec;81(9):782–790. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Castro J, Zanini M, Gonçalves Bda S, Coelho FM, Bressan R, Bittencourt L, et al. 2015. Circadian rest-activity rhythm in individuals at risk for psychosis and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. Oct;168(1-2):50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conus P, Macneil C, McGorry PD. Public health significance of bipolar disorder: implications for early intervention and prevention. Bipolar Disord. 2014. Aug;16(5):548–56. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouse J, Carpenter J, Song Y, Hockey S, Naismith S, Grunstein R, et al. 2021. Circadian rhythm sleep-wake disturbances and depression in young people: implications for prevention and early intervention. The Lancet Psych (D-20-02422R2). In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Crescenzo F, Economouc A, Sharpley A, Gormez A, Quested D. 2017. Actigraphic features of bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews 33, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Doucette S, Horrocks J, Grof P, Keown-Stoneman C, Duffy A. 2013. Attachment and temperament profiles among the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord Sep 5;150(2):522e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Duffy A, Goodday S, Keown-Stoneman C, Grof P. 2019. The emergent course of bipolar disorder: observations over two decades from the Canadian high-risk offspring cohort. Am J Psychiatr Sep 1;176(9):720e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, Keown-Stoneman C, McCloskey S, Grof P. 2014. The developmental trajectory of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry Feb;204(2):122e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faedda G, Ohashi K, Hernandez M, McGreenery C, Grant M, Baroni A, Polcari A, Teicher MH. 2016. Actigraph measures discriminate pediatric bipolar disorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and typically developing controls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Jun;57(6):706–16. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faedda G, Marangoni C, Serra G, Salvatore P, Sani G, Vázquez G, et al. 2015. Precursors of bipolar disorders: a systematic literature review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry. May;76(5):614–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Fares S, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, White D, Hickie IB, Robillard R. 2015. Clinical correlates of chronotypes in young persons with mental disorders. Chronobiol Int. 32(9):1183–91. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1078346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Faria A, Cardoso T, Campos Mondin T, Souza L, Magalhaes P, Zeni P, et al. 2015. Biological rhythms in bipolar and depressive disorders: a community study with drug-naive young adults. J Affect Disord, Jan;186, 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando J, Stochl J, Ersche KD. Drug Use in Night Owls May Increase the Risk for Mental Health Problems. Front Neurosci. 2022. Jan 11;15:819566. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.819566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy PA, Scott J, Boudebesse C, Lajnef M, Henry C, Leboyer M, Bellivier F, Etain B. 2015. Sleep in patients with remitted bipolar disorders: a meta-analysis of actigraphy studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. Feb;131(2):89–99. doi: 10.1111/acps.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Grierson AB, Hickie IB, Naismith SL, Hermens DF, Scott EM, Scott J. 2016. Circadian rhythmicity in emerging mood disorders: state or trait marker? Int J Bipolar Disord. Dec;4(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40345-015-0043-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross G, Maruani J, Vorspan F, Benard V, Benizri C, Brochard H, et al. 2020. Association between coffee, tobacco, and alcohol daily consumption and sleep/wake cycle: an actigraphy study in euthymic patients with bipolar disorders. Chronobiol Int. May;37(5):712–722. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1725542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A, Talbot L, Gershon A. 2009. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder across the lifespan. Clin. Psychol 16 (2), 256–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch T, Wozniak D, Spada J, Sander C, Ulke C, Wittekind D, et al. 2019. Vulnerability to bipolar disorder is linked to sleep and sleepiness. Transl Psychiatry. Nov 11;9(1):294. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0632-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Indic P, Salvatore P, Maggini C, Ghidini S, Ferraro G, Baldessarini RJ, Murray G. 2011. Scaling behavior of human locomotor activity amplitude: association with bipolar disorder. PLoS One. 6(5):e20650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Iorfino F, Scott EM, Carpenter JS, Cross SP, Hermens DF, Killedar M, et al. 2019. Clinical Stage Transitions in Persons Aged 12 to 25 Years Presenting to Early Intervention Mental Health Services with Anxiety, Mood, and Psychotic Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. Nov 1;76(11):1167–1175. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jones SH, Tai S, Evershed K, Knowles R, Bentall R. 2006. Early detection of bipolar disorder: a pilot familial high-risk study of parents with bipolar disorder and their adolescent children. Bipolar Disord. Aug;8(4):362–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CN, Gershon A, Depp CA, Miller S, Zeitzer JM, Ketter TA. 2018. Daytime midpoint as a digital biomarker for chronotype in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. Dec 1;241:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kim K, Weissman A, Puzia M, Cushman G, Seymour K, Wegbreit E, et al. 2014. Circadian phase preference in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Med Res, 3, 255–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioumourtzoglou M 2019. Identifying modifiable risk factors of mental health disorders-the importance of urban environmental exposures. JAMA Psychiatry Jun 1;76(6):569e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolla B, He J, Mansukhani M, Kotagal S, Frye M, Merikangas K. 2019. Prevalence and correlates of Hypersomnolence symptoms in US teens. J Am Acad ChildAdolesc Psychiatry Jul;58(7):712e20.J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold K, Ritter P, Correll CU, Marx C, Özgürdal S, Juckel G, Bauer M, Pfennig A. Risk constellations prior to the development of bipolar disorders: rationale of a new risk assessment tool. J Affect Disord. 2012. Feb;136(3):1000–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Levenson JC, Axelson DA, Merranko J, Angulo M, Goldstein TR, Mullin BC, et al. 2015. Differences in sleep disturbances among offspring of parents with and without bipolar disorder: association with conversion to bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. Dec;17(8):836–48. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Levenson JC, Soehner A, Rooks B, Goldstein TR, Diler R, Merranko J, et al. 2017. Longitudinal sleep phenotypes among offspring of bipolar parents and community controls. J Affect Disord. Jun;215:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP. Sleep and Human Aging. Neuron. 2017. Apr 5;94(1):19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour H, Wood J, Chowdari K, Dayal M, Thase M, Kupfer D, Nimgaonkar V, et al. , 2005. Circadian phase variation in bipolar I disorder. Chronobiol. Int 22 (3), 571–584. doi: 10.1081/CBI-200062413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA. 2013. How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways. Biol Psychiatry. Aug 15;74(4):242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, Keshavan M, Goldstone S, Amminger P, Allott K, Berk M, et al. 2014. Biomarkers and clinical staging in psychiatry. World Psychiatry Oct;13(3):211–23. doi: 10.1002/wps.20144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Berk M, Brietzke E, Goldstein BI, López-Jaramillo C, Kessing L, et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet. 2020. Dec 5;396(10265):1841–1856. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo M, Abreu R, Linhares Neto VB, de Bruin P, de Bruin V. 2017. Chronotype and circadian rhythm in bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. Aug;34:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo M, Garcia R, Linhares Neto VB, Sa MB, de Mesquita LM, de Araujo CF, de Bruin V. 2016. Sleep and circadian alterations in people at risk for bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. Dec;83:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mesman E, Nolen W, Keijsers L, Hillegers M. 2017. Baseline dimensional psychopathology and future mood disorder onset: findings from the Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Aug;136(2):201e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer N, Faulkner SM, McCutcheon RA, Pillinger T, Dijk DJ, MacCabe JH. 2020. Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbance in remitted schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. Mar 10;46(5):1126–43. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Meyer TD, Maier S. 2006. Is there evidence for social rhythm instability in people at risk for affective disorders? Psychiatry Res. Jan 30;141(1):103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mondin TC, Cardoso TA, Souza LD, Jansen K, da Silva Magalhães PV, Kapczinski F, da Silva RA. 2017. Mood disorders and biological rhythms in young adults: A large population-based study. J Psychiatr Res. Jan;84:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mullin BC, Harvey AG, Hinshaw SP. 2011. A preliminary study of sleep in adolescents with bipolar disorder, ADHD, and non-patient controls. Bipolar Disord. Jun;13(4):425–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TH, Chung KF, Ho FY, Yeung WF, Yung KP, Lam TH. 2015. Sleep-wake disturbance in interepisode bipolar disorder and high-risk individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. Apr;20:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004. Nov 1;27(7):1255–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancheri C, Verdolini N, Pacchiarotti I, Samalin L, Delle Chiaie R, Biondi M, et al. 2019. A systematic review on sleep alterations anticipating the onset of bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry. May;58:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pfennig A, Ritter PS, Hofler M, Lieb R, Bauer M, Wittchen HU, Beesdo-Baum K. 2016. Symptom characteristics of depressive episodes prior to the onset of mania or hypomania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. Mar;133(3):196–204. doi: 10.1111/acps.12469. Epub 2015 Aug 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter P, Marx C, Bauer M, Leopold K, Pfennig A. 2011. The role of disturbed sleep in the early recognition of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. May;13(3):227–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ritter P, Marx C, Lewtschenko N, Pfeiffer S, Leopold K, Bauer M, Pfennig A. 2012. The characteristics of sleep in patients with manifest bipolar disorder, subjects at high risk of developing the disease and healthy controls. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2012. Oct;119(10):1173–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ritter P, Hofler M, Wittchen H, Lieb R, Bauer M, Pfennig A, et al. 2015. Disturbed sleep as risk factor for the subsequent onset of bipolar disordered data from a 10-year prospective-longitudinal study among adolescents and young adults. J Psychiatr Res Sep;68:76e82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Robillard R, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Ip TK, Hermens DF, Scott EM, Hickie IB. 2013. Delayed sleep phase in young people with unipolar or bipolar affective disorders. J Affect Disord. Feb 20;145(2):260–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Robillard R, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, White D, Rogers NL, Ip TK, et al. 2015. Ambulatory sleep-wake patterns and variability in young people with emerging mental disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. Jan;40(1):28–37. doi: 10.1503/jpn.130247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Robillard R, Oxley C, Hermens DF, White D, Wallis R, Naismith SL, et al. 2016. The relative contributions of psychiatric symptoms and psychotropic medications on the sleep-wake profile of young persons with anxiety, depression and bipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res. Sep 30;243:403–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rock P, Goodwin G, Harmer C, Wulff K. 2014. Daily rest-activity patterns in the bipolar phenotype: A controlled actigraphy study. Chronobiol Int. Mar;31(2):290–6. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.843542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scott J, Byrne E, Medland S, Hickie I. 2020a. Short communication: Self-reported sleep-wake disturbances preceding onset of full-threshold mood and/or psychotic syndromes in community residing adolescents and young adults. J Affect Disord. Dec 1;277:592–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Colom F, Young A, Bellivier F, Etain B. 2020b. An evidence map of actigraphy studies exploring longitudinal associations between rest-activity rhythms and course and outcome of bipolar disorders. Int J Bipolar Disord. Dec 1;8(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s40345-020-00200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Kallestad H, Vedaa O, Sivertsen B, Etain B. 2021. Sleep disturbances and first onset of major mental disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. Jun; 57:101429. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Marwaha S, Ratheesh A, Macmillan I, Yung AR, Morriss R, Hickie IB, Bechdolf A. Bipolar At-Risk Criteria: An Examination of Which Clinical Features Have Optimal Utility for Identifying Youth at Risk of Early Transition From Depression to Bipolar Disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2017. Jul 1;43(4):737–744. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Murray G, Henry C, Morken G, Scott E, Angst J, Merikangas KR, Hickie IB. 2017. Activation in Bipolar Disorders: A Systematic Review. JAMA Psychiatry. Feb 1;74(2):189–196. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scott J, Naismith S, Grierson A, Carpenter J, Hermens D, Scott E, Hickie I. 2016. Sleep-wake cycle phenotypes in young people with familial and non-familial mood disorders. Bipolar Disord. Dec;18(8):642–649. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sebela A, Kolenic M, Farkova E, Novak T, Goetz M. 2019. Decreased need for sleep as an endophenotype of bipolar disorder: an actigraphy study. Chronobiol Int. Sep;36(9):1227–1239. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2019.1630631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Shen GH, Sylvia LG, Alloy LB, Barrett F, Kohner M, Iacoviello B, Mills A. 2008. Lifestyle regularity and cyclothymic symptomatology. J Clin Psychol. Apr;64(4):482–500. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou H, Cui L, Hickie I, Lameira D, Lamers F, Zhang J, et al. 2017. Dysregulation of objectively assessed 24-hour motor activity patterns as a potential marker for bipolar I disorder: results of a community-based family study. Transl Psychiatry. Aug 22;7(8):e1211. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Soehner AM, Bertocci MA, Manelis A, Bebko G, Ladouceur CD, Graur S, et al. 2016. Preliminary investigation of the relationships between sleep duration, reward circuitry function, and mood dysregulation in youth offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. Nov 15;205:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaesu Y 2018. Circadian rhythm in bipolar disorder: A review of the literature. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018 Sep;72(9):673–682. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazawa Y, Wada M, Mitsukura Y, Takamiya A, Kitazawa M, Yoshimura M, Kishimoto T. Actigraphy for evaluation of mood disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord, 2019. 253, 257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thun E, Bjorvatn B, Osland T, Steen V, Sivertsen B, Johansen T, et al. 2012. An actigraphic validation study of seven morningness-eveningness inventories. Eur. Psychol 17 (3), 222–230. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti L, Adan A, Di Milia L, Randler C, Natale V. 2015. Measures of circadian preference in childhood and adolescence: A review. Eur. Psychiatry 30 (5), 576–582. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek J, Spira A, Di J, Leroux A, Crainiceanu C, Zipunnikov V. 2018. Epidemiology of objectively measured bedtime and chronotype in the US adolescents and adults: NHANES 2003-2006. Chronobiol. Int 35 (3), 416–434. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1411359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallarino M, Henry C, Etain B, Gehue LJ, Macneil C, Scott EM, et al. 2015. An evidence map of psychosocial interventions for the earliest stages of bipolar disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. Jun;2(6):548–63. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00156-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CH, Chen KC, Hsu WY, Lee IH, Chiu NY, Chen PS, Yang YK. 2014. Sleep complaints and memory in psychotropic drug-free euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Formos Med Assoc. May;113(5):298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wescott D, Morash-Conway J, Zwicker A, Cumby J, Uher R, Rusak B. 2019. Sleep in offspring of parents with mood disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 225. doi. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangani C, Casetta C, Saunders A, Donati F, Maggioni E, D’Agostino A. 2020. Sleep abnormalities across different clinical stages of bipolar disorder: A review of EEG studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 118, 247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Zanini MA, Castro J, Cunha GR, Asevedo E, Pan PM, Bittencourt L, et al. 2015. Abnormalities in sleep patterns in individuals at risk for psychosis and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. Dec;169(1-3):262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.