Abstract

Background:

Many states have legalized recreational cannabis use for adults. However, no study has examined how this policy may interact with youth vaping to influence cannabis use among US adolescents. This study investigates whether the association between baseline e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use differs by state recreational cannabis legalization status.

Methods:

This study analyzed data from the first four waves (2013–2018) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, a nationally representative longitudinal survey. The study sample included adolescents (aged 12–17) who reported never used cannabis at baseline. Generalized estimating equations were used to analyze the effect modification of state recreational cannabis law on the association between baseline e-cigarette use and cannabis use at 12-month follow-up, controlling for individual characteristics.

Results:

Among adolescents who have never used cannabis at baseline, baseline past-30-day e-cigarette use was significantly associated with past-30-day cannabis use at 12-month follow-up (aOR=5.92, 95% CI: 3.52–9.95). This association was different by state recreational cannabis legalization status, as indicated by the significant interaction term. Subgroup analysis showed that the aOR was 18.39 (95% CI: 4.25–79.68) for adolescents living in states that legalized adult recreational cannabis use and 5.09 (95% CI: 2.86–9.07) for adolescents living in states without such laws.

Conclusions:

E-cigarette use is associated with cannabis initiation among youth. This association is stronger among those living in states that legalized adult recreational cannabis use. Further examination of the impact of e-cigarette use on cannabis initiation in relation to state cannabis laws is warranted.

Keywords: Adolescents, Cannabis use, E-cigarette use, State recreational cannabis legalization, Youth cannabis prevention

1. Introduction

Cannabis is the most widely used psychoactive substance among US youth, with 21.1% of 12th graders, 16.6% of 10th graders, and 6.5% of 8th graders reporting using cannabis in the past 30 days in 2020 (Johnston et al., 2021). Although cannabis remains a Schedule I drug at the federal level, more states are legalizing recreational cannabis use for adults aged 21 years and older in recent years (Yu et al., 2020). In 2019, Illinois became the 11th state legalizing cannabis for adult recreational use, joining Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, and the District of Columbia, which had already passed such laws (Stracqualursi, 2019). Since 2020, at least five more states, Arizona, Montana, New Jersey, New York, and South Dakota, have approved legalizing recreational cannabis use for adults (Dezenski, 2020). Previous studies have demonstrated that state cannabis policies may be associated with adolescent cannabis use, abuse, and dependence (Cerdá et al., 2017; Cerdá et al., 2012). Legalizing recreational cannabis use for adults may influence adolescents’ risk perception and perceived product availability, including diminished harm perceptions towards cannabis use and increased perceived accessibility and availability of cannabis products (Ladegard et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018). For example, although there may be various long-term adverse health effects of chronic cannabis use among adolescents (Bagot et al., 2015; Bechtold et al., 2015), the proportion of 12th-graders perceiving regular cannabis use as harmful have declined substantially from approximately 80% in the 1990s to about 30% in 2020 (Johnston et al., 2021).

E-cigarettes are gaining popularity among US youth. In 2020, 19.6% of high school students and 4.7% of middle school students reported e-cigarette use in the past 30 days (Wang et al., 2020). Many e-cigarette devices can be customized by users to deliver liquid THC (tetrahydrocannabinol, the psychoactive ingredient in cannabis) or hash oil (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2016). The outbreak of EVALI in 2019 highlighted the risks of using electronic vaping products to vape THC among US youth and young adults (Kalininskiy et al., 2019; Nicksic et al., 2020). A growing body of literature indicates a putative prospective association between initial e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis vaping and other forms of cannabis use among adolescents (Evans-Polce et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). A recent meta-analysis revealed that the pooled odds of cannabis use among adolescent e-cigarette users were 3.5 times the corresponding odds among non-e-cigarette users (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=3.47; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]=2.63–4.59) (Chadi et al., 2019).

State laws permitting recreational cannabis use among adults have been demonstrated to be associated with cannabis use and other drug abuse among adolescents (Cerdá et al., 2020; Cerdá et al., 2017). The legalization of recreational cannabis use for adults coincides with changes in the risk perceptions and social acceptability of cannabis use among adolescents, it may also increase youth’s access to cannabis products and contribute to cannabis use among adolescents (Berg et al., 2015). However, little is known about whether legalizing recreational cannabis use would interact with other risk factors of cannabis use and further elevate the likelihood of cannabis initiation among adolescents, particularly with regard to its interaction with e-cigarette use among adolescents, given that a wide variety of electronic vaping products containing THC or cannabidiol (King et al., 2020). In this study, we hypothesized that adolescent e-cigarette users living in states that legalized recreational cannabis use for adults would be more likely to initiate cannabis use compared to their counterparts living in states where adult recreational cannabis use was not legalized.

In addition to e-cigarette use, existing evidence shows that adolescents with mental health disorders are more likely to use nicotine and other substance, leading to substance addiction (Duan et al., 2021b; Riehm et al., 2019). For example, youth with internalizing mental health problems are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety, and therefore more likely to use tobacco/cannabis to help cope with these symptoms (Groenman et al., 2017). Youth with externalizing mental health problems, however, tend to have more issues related to behavioral conducts, and thus are more likely to use tobacco/cannabis as a way to rebel against health behaviors considered to be “normal” or “acceptable” (Luthar and Ansary, 2005). Despite their documented importance, few previous studies examining the association between e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use accounted for the potential confounding effects of individual mental health conditions.

This study aims to fill these research gaps by examining the potential effect modification of recreational cannabis legalization on the association between e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use among US adolescents, controlling for various confounders, such as mental health condition and use of combustible tobacco products, which were not previously accounted for. Specifically, we used the youth data from of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study to investigate whether the magnitude of the prospective association between e-cigarette use at baseline and cannabis use at follow-up vary by state recreational cannabis legalization status, controlling for individual socio-demographic characteristics, use of combustible tobacco products, and mental health conditions.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data and study design

Data used for this observational study were compiled from Wave 1–4 youth cohort of the PATH Study (2013–2018), a household-based, nationally representative, longitudinal study. A multistage, stratified probability sample was selected to represent the noninstitutionalized youth population in the US. Youth aged 9–17 years old were selected before Wave 1 data collection. Youth aged 12–17 years old were eligible for the survey, and youth aged 9 to 11 years old would be interviewed when they aged up to 12 years old at follow-up waves. Detailed sampling methods and study design of the PATH Study are published elsewhere (Hyland et al., 2017). This study followed an approach used by the PATH study data management and research team that stacked covariates in the baseline wave with cannabis use status at its corresponding follow-up wave (Kasza et al., 2020), where Wave 1–3 each was considered as the baseline wave of its subsequent 12-month follow-up wave. For instance, Wave 2 was both the follow-up wave of Wave 1 and the baseline wave for Wave 3.

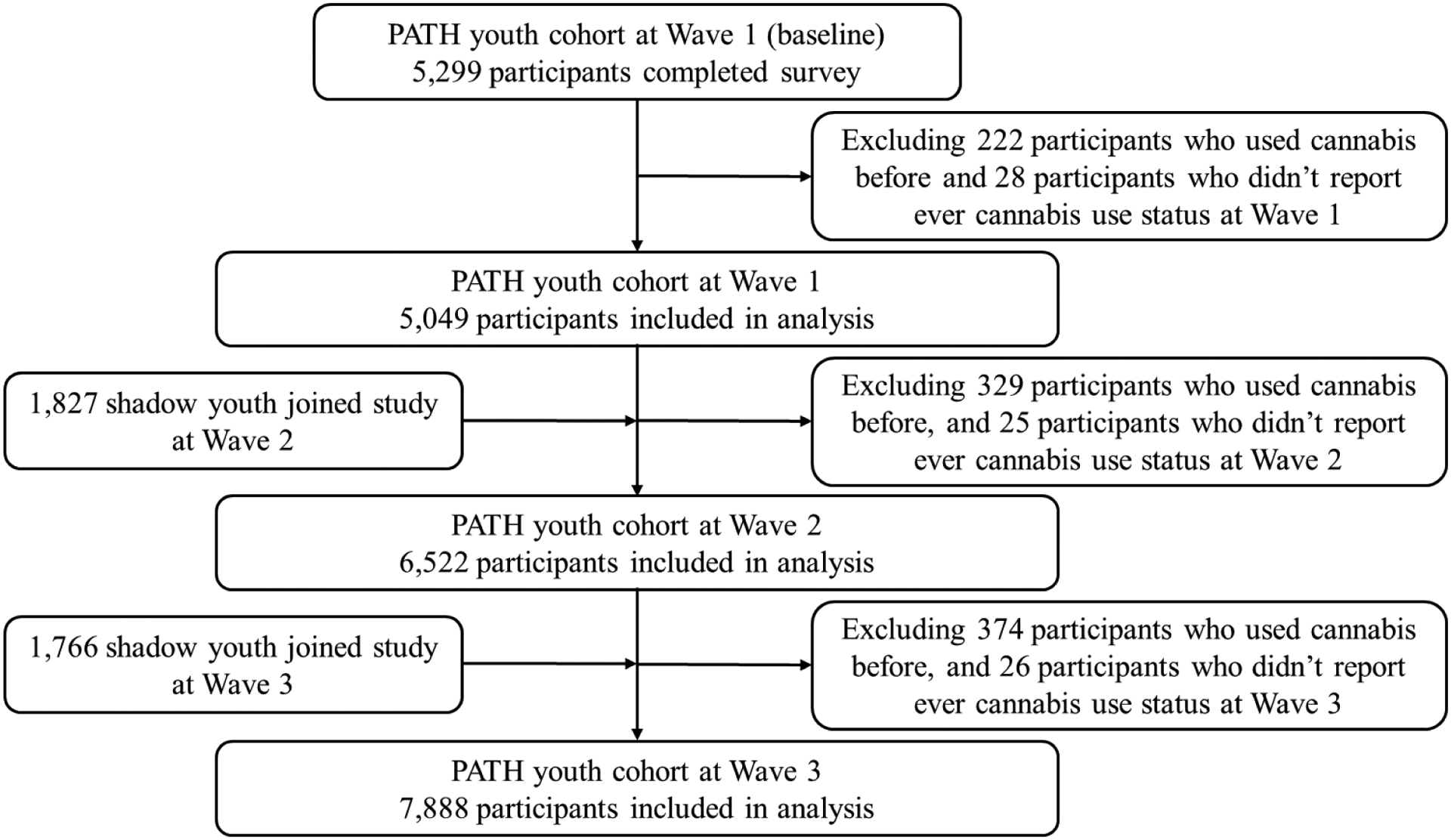

The target population of this study was youth respondents who reported having never used cannabis at baseline waves. To produce nationally representative estimates, we followed the recommended approach by the PATH Study team to apply the youth cohort all-wave weights to the study sample. The all-wave weights were restricted to Wave 1 respondents and shadow youth who completed interviews of all waves while they were 12–17 years old (Hyland et al., 2017). Therefore, only never cannabis users at baseline waves with all-wave weights were included in this study. The study sample includes 19,503 adolescents who reported never using cannabis at baseline waves assessed over up to three waves, resulting in 5,049 participants at Wave 1, 6,566 participants at Wave 2, and 7,888 participants at Wave 3. The study sample enrollment and exclusion procedures are illustrated in the Figure 1 flowchart. Since only secondary data analyses of the de-identified PATH data were conducted, this study was determined by the Georgia State University (GSU) Institutional Review Board (IRB) to be non-human subject research.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for participants included in final analyses.

2.2. Measures

The primary outcome was self-reported binary past-30-day (P30D) cannabis use at 12-month follow-up waves. At the follow-up waves, study participants (never cannabis users at baseline waves) who reported having “used marijuana, hash, THC, grass, pot or weed” or having “smoked part or all of a cigar, cigarillo, or filtered cigar with marijuana in it” in the past 30 days prior to the survey were coded as P30D cannabis users. The primary exposure variable was baseline P30D e-cigarette use. Participants who reported using any e-cigarette products in the past 30 days at baseline waves were coded as baseline P30D e-cigarette users. Recreational cannabis legalization status (adult recreational cannabis use legalized or not) at the time of survey administration, the putative effect modifier, was compiled from the NIH Alcohol Policy Information System (NIH Alcohol Policy Information System). State identifiers provided in the PATH Study Restricted-Use Files were used to link state cannabis laws with individual respondents.

Other covariates in this study included survey wave, age (12–14 or 15–17), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, or Non-Hispanic Other), parental education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college or associate degree, and bachelor’s degree or above), P30D use of combustible tobacco products (cigarettes, traditional cigars, cigarillos, or filtered cigars), and internalizing and externalizing mental health status. The PATH youth survey incorporated four items measuring internalizing mental health conditions and seven items measuring externalizing mental health conditions (Table A1). In this study, we followed a validated approach to sum up the scores and categorize the severity of mental health problems to low (0–1), moderate (2–3), and high (4 for internalizing problems or 4–7 for externalizing problems) (Conway et al., 2018).

2.3. Data analysis

All data management and analyses were conducted using Stata 15 (StataCorp LLC. College Station, TX). The youth cohort all-wave weights were applied to account for the complex sampling design and produce nationally representative estimates. The weighted prevalence of P30D cannabis use at each follow-up wave was estimated overall and by covariates at its corresponding baseline wave. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) with unstructured covariance was fitted to evaluate the prospective association between baseline e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use over three 12-month follow-up periods (Wave 1 to Wave 2, Wave 2 to Wave3, and Wave 3 to Wave 4), controlling for survey waves, individual characteristics and state recreational cannabis legalization status (Hardin, 2005). A second GEE model was fitted to examine the potential effect modification of recreational cannabis laws on the association between baseline e-cigarette use and cannabis use at follow-up waves. Subgroup analyses were then conducted to compare the magnitudes of this association for respondents living in states with/without adult recreational cannabis use legalization. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted based on the same set of analyses described above in which the outcome measures were replaced with ever cannabis use during the follow-up period. All null hypothesis statistical tests were two-sided with the significance level α=0.05.

3. Results

Our study sample included 19,503 adolescents who reported having never used cannabis at baseline waves assessed over up to three 12-month follow-up waves. The enrollment and exclusion criteria and procedures are illustrated in Figure 1. Among youth who reported never having used cannabis at Wave 1, 49.0% of respondents were female, 54.3% were Non-Hispanic White, 14.1% were Non-Hispanic Black, 9.3% were Non-Hispanic Other, and 22.3% were Hispanic. The sex and race/ethnicity proportions were consistent across three baseline waves. Detailed descriptive statistics of other demographic characteristics, tobacco use status, and mental health problems were presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of e-cigarette use and covariates at baseline waves.

| Exposure and covariates | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Total, No. | 5049 | 6522 | 7888 |

| P30D e-cigarette use | |||

| Yes | 29 (0.6) | 55 (0.9) | 103 (1.4) |

| No | 4989 (99.4) | 6425 (99.1) | 7756 (98.6) |

| State recreational cannabis law | |||

| Legalized | 340 (6.2) | 444 (6.2) | 1607 (18.8) |

| Not legalized | 4709 (93.8) | 6708 (93.8) | 6281 (81.2) |

| Age group | |||

| 12–14 | 4881 (96.7) | 5116 (77.8) | 5130 (65.0) |

| 15–17 | 168 (3.3) | 1406 (22.2) | 2758 (35.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2580 (51.0) | 3311 (51.0) | 4032 (51.0) |

| Female | 2469 (49.0) | 3191 (49.0) | 3832 (49.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2405 (54.3) | 3011 (53.7) | 3594 (52.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 715 (14.1) | 845 (13.3) | 994 (12.9) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 455 (9.3) | 585 (9.8) | 728 (10.3) |

| Hispanic | 1474 (22.3) | 1856 (23.2) | 2251 (24.0) |

| P30D combustible tobacco usea | |||

| Yes | 30 (0.6) | 42 (0.6) | 53 (0.7) |

| No | 4840 (99.4) | 6454 (99.4) | 7805 (99.3) |

| Internalizing mental health problems | |||

| Low | 2574 (52.3) | 3400 (53.1) | 3928 (51.3) |

| Moderate | 1447 (29.3) | 1757 (27.8) | 2152 (28.2) |

| High | 879 (18.4) | 1207 (19.1) | 1585 (20.5) |

| Externalizing mental health problems | |||

| Low | 1917 (39.6) | 2762 (44.0) | 3335 (43.9) |

| Moderate | 1460 (30.7) | 1715 (27.9) | 2041 (27.6) |

| High | 1392 (29.7) | 1738 (28.1) | 2137 (28.4) |

| Parental education | |||

| Less than high school | 1017 (17.4) | 1169 (16.5) | 1430 (15.7) |

| High school graduate | 928 (17.5) | 1071 (16.8) | 1344 (16.3) |

| Some college or associate degree | 1045 (20.1) | 1852 (30.3) | 2451 (31.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 2033 (45.0) | 1898 (36.3) | 2498 (36.8) |

Combustible tobacco included cigarettes, traditional cigar, cigarillo, or filtered cigar.

P30D, past-30-day.

Table 2 shows the weighted percentages of P30D cannabis use at each follow-up wave by covariates at its corresponding baseline wave. Among adolescents who reported never using cannabis and reported P30D e-cigarette use at baseline wave, the percentage of P30D cannabis use was 13.8% (95% CI: 4.3%−36.1%) at Wave 2, 9.7% (95% CI: 4.3%−20.2%) at Wave 3, and 26.3% (95% CI: 18.0%−36.7%) at Wave 4, respectively. By contrast, among adolescents who reported never use of cannabis and did not report P30D e-cigarette use at the baseline waves, the percentage of P30D cannabis use was 2.2% (95% CI: 1.8%−2.8%) at Wave 2, 2.4% (95% CI: 2.0%−2.8%) at Wave 3, and 2.9% (95% CI: 2.6%−3.2%) at Wave 4, respectively. Among adolescents who lived in states legalizing recreational cannabis use for adults, the weighted percentages of P30D cannabis use were 3.4% (95% CI: 1.6%−7.3%) at Wave 2, 2.9% (95% CI: 1.3%−6.4%) at Wave 3, and 3.4% (95% CI: 2.6%−4.4%) at Wave 4. Among those living in states not legalizing recreational cannabis use, the weighted percentages of P30D cannabis use were 2.2% (95% CI: 1.8%−2.8%) at Wave 2, 2.4% (95% CI: 2.0%−2.9%) at Wave 3, and 3.2% (95% CI: 2.6% - 4.4%) at Wave 4. In addition, the weighted percentages of self-reported P30D cannabis use at follow-up waves were higher among adolescents who were older, used combustible tobacco products, and experienced more severe internalizing or externalizing mental health problems. The weighted distributions of covariates by P30D e-cigarette use were presented in Table A2.

Table 2.

Weighted percentages of P30D cannabis use in 12-month follow-up waves by covariates.

| Covariates at corresponding baseline wave | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Overall P30D cannabis use | 2.3 (1.8 – 2.9) | 2.4 (2.0 – 2.9) | 3.2 (2.9 – 3.6) |

| P30D e-cigarette use | |||

| Yes | 13.8 (4.3 – 36.1) | 9.7 (4.3 – 20.2) | 26.3 (18. 0 – 36.7) |

| No | 2.2 (1.8 – 2.8) | 2.4 (2.0 – 2.8) | 2.9 (2.6 – 3.2) |

| State recreational cannabis law | |||

| Legalized | 3.4 (1.6 – 7.3) | 2.9 (1.3 – 6.4) | 3.4 (2.6 – 4.4) |

| Not legalized | 2.2 (1.8 – 2.8) | 2.4 (2.0 – 2.9) | 3.2 (2.6 – 4.4) |

| Age group | |||

| 12–14 | 2.3 (1.8 – 2.9) | 2.0 (1.6 – 2.5) | 2.4 (2.0 – 2.8) |

| 15–17 | 2.4 (0.8 – 6.8) | 3.9 (3.0 – 5.2) | 4.8 (4.0 – 5.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.8 (1.3 – 2.6) | 2.4 (1.9 – 3.0) | 3.0 (2.5 – 3.7) |

| Female | 2.8 (2.1 – 3.6) | 2.5 (1.9 – 3.2) | 3.4 (2.8 – 4.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.4 (1.8 – 3.2) | 2.6 (2.0 – 3.3) | 3.7 (3.1 – 4.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3.5 (2.1 – 5.8) | 1.8 (1.1 – 3.1) | 3.2 (2.2 – 4.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.8 (0.3 – 2.6) | 2.3 (1.2 – 4.1) | 1.2 (0.6 – 2.1) |

| Hispanic | 1.9 (1.2 – 2.8) | 2.4 (1.8 – 3.3) | 3.2 (2.6 – 4.1) |

| P30D combustible tobacco usea | |||

| Yes | 12.9 (4.5 – 31.7) | 14.8 (6.8 – 29.4) | 18.9 (10. 8 – 31.0) |

| No | 2.3 (1.8 – 2.9) | 2.4 (2.0 – 2.8) | 3.1 (2.7 – 3.4) |

| Internalizing mental health problems | |||

| Low | 1.3 (0.9 – 1.9) | 1.9 (1.5 – 2.5) | 2.7 (2.2 – 3.2) |

| Moderate | 2.4 (1.7 – 3.4) | 2.3 (1.7 – 3.1) | 3.1 (2.4 – 4.0) |

| High | 5.1 (3.7 – 7.1) | 4.2 (3.1 – 5.7) | 4.9 (4.0 – 6.0) |

| Externalizing mental health problems | |||

| Low | 1.1 (0.7 – 1.8) | 1.9 (1.4 – 2.6) | 2.3 (1.8 – 2.8) |

| Moderate | 2.1 (1.4 – 3.0) | 1.9 (1.3 – 2.7) | 3.3 (2.6 – 4.2) |

| High | 4.4 (3.3 – 5.9) | 3.7 (2.9 – 4.7) | 4.7 (3.9 – 5.7) |

| Parental education | |||

| Less than high school | 4.2 (3.2 – 5.7) | 2.1 (1.3 – 3.2) | 3.9 (3.0 – 4.9) |

| High school graduate | 2.1 (1.2 – 3.5) | 2.3 (1.4 – 3.6) | 3.2 (2.3 – 4.5) |

| Some college or associate degree | 2.0 (1.3 – 3.0) | 3.4 (2.5 – 4.5) | 3.5 (2.9 – 4.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 1.8 (1.2 – 2.7) | 1.9 (1.3 – 2.7) | 2.6 (2.1 – 3.3) |

Combustible tobacco included cigarettes, traditional cigar, cigarillo, or filtered cigar.

CI, confidence interval; P30D, past-30-day.

Table 3 shows the adjusted associations between P30D cannabis use at follow-up waves and baseline characteristics among adolescents who reported never used cannabis at baseline waves. Adolescents who reported P30D e-cigarette use at baseline waves were significantly more likely to report P30D cannabis use at follow-up waves (aOR=5.92, 95% CI: 3.52–9.95, p<0.001), after adjusting for individual characteristics and state recreational cannabis laws (Model 1). The association between recreational cannabis legalization and the onset of cannabis use at 12-month follow-up was not statistically significant (aOR=1.29, 95% CI: 0.97–1.72). Older age, using combustible tobacco, and more severe internalizing or externalizing mental health problems at baseline waves were significantly associated with elevated odds of P30D cannabis use at follow-up waves, with other characteristics being constant. In addition, being Non-Hispanic Other and having parents with a bachelor’s degree or above were associated with reduced odds of P30D cannabis use at follow-up waves. Notably, the interaction term, denoted as “P30D e-cigarette use # state recreational cannabis laws”, was statistically significant (Model 2). This result indicated that the association between baseline e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use was significantly different between adolescents living in states that legalized recreational cannabis use and those living in states that did not legalize recreational cannabis use for adults.

Table 3.

Adjusted ORs of P30D cannabis use in 12-month follow-up waves.

| Baseline exposure and covariates | Model 1 - No interaction | Model 2 - Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| P30D e-cigarette use | ||

| Yes | 5.92 (3.52 – 9.95) | 5.06 (2.86 – 8.95)c |

| No | Reference | Reference |

| State recreational cannabis law | ||

| Legalized | 1.29 (0.97 – 1.72) | 1.22 (0.91 – 1.64) |

| Not legalized | Reference | Reference |

| P30D e-cigarette use # state recreational cannabis lawa | ||

| Yes # Legalized | 3.94 (1.01 – 15.47) | |

| No # Not legalized | Reference | |

| Age group | ||

| 14-Dec | Reference | Reference |

| 15–17 | 1.80 (1.44 – 2.26) | 1.81 (1.44 – 2.26) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 0.91 (0.74 – 1.12) | 0.91 (0.74 – 1.12) |

| Female | Reference | Reference |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.04 (0.76 – 1.42) | 1.04 (0.76 – 1.42) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.51 (0.33 – 0.79) | 0.51 (0.33 – 0.80) |

| Hispanic | 0.86 (0.65 – 1.13) | 0.86 (0.65 – 1.13) |

| Parental education | ||

| Less than high school | Reference | Reference |

| High school graduate | 0.71 (0.51 – 1.01) | 0.70 (0.50 – 0.99) |

| Some college or associate degree | 0.82 (0.60 – 1.12) | 0.82 (0.60 – 1.12) |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 0.61 (0.44 – 0.85) | 0.61 (0.43 – 0.85) |

| P30D combustible tobacco useb | ||

| Yes | 2.68 (1.36 – 5.29) | 2.79 (1.41 – 5.49) |

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Internalizing mental health problems | ||

| Low | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate | 1.08 (0.81 – 1.43) | 1.07 (0.81 – 1.42) |

| High | 1.50 (1.10 – 2.05) | 1.49 (1.09 – 2.04) |

| Externalizing mental health problems | ||

| Low | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate | 1.25 (0.94 – 1.68) | 1.25 (0.94 – 1.68) |

| High | 1.79 (1.30 – 2.45) | 1.79 (1.31 – 2.46) |

Interaction term of P30D e-cigarette use and state recreational cannabis law.

Combustible tobacco included cigarettes, traditional cigar, cigarillo, or filtered cigar.

This is the estimated association between P30D e-cigarette use at baseline and P30D cannabis use at follow-up among those living in non-legal states due to the existence of the interaction term. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; P30D, past-30-day.

Results of subgroup analysis stratified by state recreational cannabis law were presented in Table 4. Among adolescents living in states that legalized recreational cannabis use for adults, the adjusted OR between baseline P30D e-cigarette use and P30D cannabis use at follow-up waves was 18.39 (95% CI: 4.25–79.68), controlling for individual characteristics. In contrast, among adolescents living in states that did not legalize recreational cannabis use for adults, the corresponding adjusted OR was 5.09 (95% CI: 2.86–9.07).

Table 4.

Adjusted ORa of subgroup analysis for adolescents living in states legalizing or not legalizing recreational cannabis use.

| P30D cannabis use in states legalizing recreational cannabis use | P30D cannabis use in states not legalizing recreational cannabis use | |

|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| P30D e-cigarette use | ||

| Yes | 18.39 (4.25 – 79.68) | 5.09 (2.86 – 9.07) |

| No | Reference | Reference |

Controlling for P30D combustible tobacco use, sex, age, race/ethnicity, parental education, past-year internalizing mental health problems, past-year externalizing mental health problems.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; P30D, past-30-day.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by replacing the P30D outcome measure with ever cannabis use during the 12-month follow-up period. Consistent with the results in Table 2, results presented in Table A3 showed that at each follow-up wave, the weighted prevalence of ever cannabis use was higher among adolescents who reported baseline P30D e-cigarette use, compared with those who did not. In addition, results in Table A4 were consistent with those in Table 3 regarding the significance of the interaction term between e-cigarette use and state recreational cannabis legalization. Furthermore, the results of subgroup analyses in Table A5 consistently indicated that the association between baseline P30D e-cigarette use and ever cannabis use at follow-up waves was stronger among adolescents living in states that legalized recreational cannabis use (aOR=15.93, 95% CI: 4.51–56.26), compared with those living in states that did not legalize recreational cannabis use for adults (aOR=3.24, 95% CI: 2.02–5.22).

4. Discussion

Although many states in the US have legalized recreational cannabis use for adults, the potential impact of cannabis legalization for adults on adolescent cannabis initiation in the context of youth vaping epidemic has received minimal research attention (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2017). This study provides important evidence regarding the association between youth e-cigarette use and cannabis initiation in relation to state cannabis legalization status using the PATH data collected from 2013 to 2018, a period when substantial changes occurred in both the e-cigarette marketplace and the state cannabis policy landscape (Duan et al., 2021a; Huang et al., 2019). Consistent with previous studies, we observed a positive prospective association between baseline e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use among adolescents (Chadi et al., 2019; Evans-Polce et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). In addition, our study showed a positive, albeit insignificant, association between state recreational cannabis legalization and the onset of cannabis use at 12-month follow-up (aOR=1.29, 95% CI: 0.97–1.72). Previous studies indicated that legalizing recreational cannabis use for adults substantially affect youth’s knowledge, risk perceptions, and use behaviors of cannabis (Cerdá et al., 2020; Mason et al., 2015). The legalization and marketing of cannabis products might lower the perceived risk and increase the social acceptability of cannabis use (Berg et al., 2015), and increase access to cannabis products among adolescents (Cerdá et al., 2017; Miech et al., 2017). The borderline insignificant result in our study may be partially due to the small sample size of adolescent cannabis users and the relatively short follow-up period.

Our analyses showed that adolescent e-cigarette users living in states with recreational cannabis laws were much more likely (aOR=18.39, 95% CI: 4.25–79.68) to use cannabis at follow-up than their counterparts living in states without such laws (aOR=5.09, 95% CI: 2.86–9.07), indicating that state recreational cannabis legalization was associated with increased odds of cannabis initiation among adolescent e-cigarette users. For adolescents who reported never used cannabis and lived in states that legalized recreational cannabis use for adults, e-cigarette use was associated with significantly increased risk of subsequent cannabis initiation. This differential association by state recreational cannabis law may be partially attributable to the fact that legalizing recreational use of cannabis products may lower the perceived risk and increase the social acceptability of cannabis use and increase access to cannabis products among e-cigarette using adolescents (Berg et al., 2015; Cerdá et al., 2017; Miech et al., 2017). The revelation of the interaction between recreational cannabis legalization and e-cigarette use on the onset of cannabis use is one of the most important contributions of this study. This finding was based on the between-subjects comparisons, i.e., comparing those living in states with vs. without adult recreational cannabis laws. Our analysis did not isolate the causal impact of the state cannabis laws as our study sample setup did not permit examining the within-subject variations in cannabis use behaviors in relation to changes in state laws over time. It is possible that the stronger association between e-cigarette use and cannabis use among those living in states that legalized adult recreational cannabis use may reflect the increased use of both products among peers and parents. Further studies are needed to clarify the pathways in which the state cannabis laws influence cannabis use among e-cigarette using youth.

In addition, we found a positive association between baseline externalizing mental health problems and the onset of cannabis use at follow-up. This finding is consistent with what was reported in previous studies, which showed that more severe externalizing mental health problems was a robust predictor of adolescent substance use (Colder et al., 2018; Pedersen et al., 2018). We also found a positive association between high level severity of internalizing mental health problems and cannabis use. The evidence on the impact of internalizing mental health problems on substance use has been mixed so far (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2020; Colder et al., 2018). One potential explanation is that while adolescents with internalizing mental health problems are more likely to use cannabis to cope with anxiety/depression, they also tend to be more socially isolated and less likely to get cannabis from peers or use cannabis with peers (Scalco et al., 2014). Our results suggest early screening for mental health problems combined with targeted mental health interventions (e.g., preventive efforts through primary care providers, or targeted school counseling for adolescents with mental health problems) may help reduce cannabis initiation among adolescents (Flay, 2009).

Other baseline factors associated with elevated odds of cannabis use at follow-up waves include age and combustible tobacco use status. Specifically, we found older adolescents were more likely to use cannabis at 12-month follow-up, a finding consistent with what’s reported by previous studies (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2018). Older adolescents likely have more sources to access cannabis products and lower levels of perceived risks of cannabis use, thus more likely to initiate using cannabis products compared with their younger counterparts (King et al., 2016). In addition, our study found that adolescents who used combustible tobacco products at baseline waves were more likely to use cannabis at follow-up waves, also consistent with previous findings (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2018; Evans-Polce et al., 2020). This result indicated that youth tobacco users were at elevated odds of using substances in the future. These results suggest that efforts to reduce youth cannabis use may need to include interventions and health campaigns targeted at youth tobacco users.

This study is subject to several limitations. One limitation is that our results reflect the perspective population-average associations between baseline characteristics and outcomes at 12-month over three follow-up periods. They did not represent the causality between e-cigarette use and cannabis use in relation to state cannabis laws. However, this study controlled for a wide range of potential confounders, including individual-level socio-demographic characteristics, use of combustible tobacco products, and mental health status, and established a temporal association between e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis use. Our sample setup did not permit an examination of the causal impact of state cannabis laws on cannabis use by using the within-subject change over time, which could be examined by future studies using a fixed-effect model. Second, self-reported use of cannabis and tobacco products may introduce recall bias and social desirability bias. Third, this study included US adolescents aged 12 to 17 years old from 2013 to 2018, and the results may not be generalized to other age groups or countries. Fourth, the sample size of e-cigarette using youth living in states legalizing recreational cannabis use was small, which led to the wide confidence intervals in subgroup analysis. Finally, due to data availability, mediation analyses were not allowed to examine whether the risk perceptions and availability of cannabis products may contribute to the differential patterns from e-cigarette use to cannabis use between adolescents living in states where recreational cannabis use for adults was legalized vs. not legalized. Future quantitative and qualitative studies are needed to explore the impact of state recreational cannabis laws on cannabis use among adolescent e-cigarette users in the context of youth vaping epidemic.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed the effect modification of recreational cannabis legalization on the association between baseline e-cigarette use and subsequent cannabis initiation. The results suggest that adolescent e-cigarette users who live in states that legalized recreational cannabis use for adults are associated with higher risk of initiating cannabis use. The study findings highlight the importance of the interaction of youth vaping epidemic and state cannabis laws in shaping youth use of cannabis. Future studies are needed to better understand the causal mechanisms of state adult recreational cannabis laws on cannabis use among adolescents in the context of youth vaping epidemic.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Association between youth e-cigarette use and future cannabis use was evaluated

Effect modification of state recreational cannabis policy was examined

Baseline e-cigarette use was associated with increased likelihood of cannabis use

State recreational cannabis law may increase cannabis onset among e-cigarette users

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01CA194681]. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Role of Funding Source:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01CA194681]. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NCI, or FDA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dr. Duan conceptualized the research question and designed the study, conducted the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript; Yu Wang conducted the analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs. Weaver, Spears, Zheng, Self-Brown, and Eriksen contributed to the study conceptualization and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, Dr. Huang conceptualized and designed the study, critically revised and manuscript, and secured the funding. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reference

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Testa S, Alexander E, Pianin S, 2020. Adolescent E-Cigarette Onset and Escalation: Associations With Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms. Journal of Adolescent Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Stone MD, Barrington-Trimis J, Unger JB, Leventhal AM, 2018. Adolescent e-cigarette, hookah, and conventional cigarette use and subsequent marijuana use. Pediatrics 142(3), e20173616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagot KS, Milin R, Kaminer Y, 2015. Adolescent initiation of cannabis use and early-onset psychosis. Substance Abuse 36(4), 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold J, Simpson T, White HR, Pardini D, 2015. Chronic adolescent marijuana use as a risk factor for physical and mental health problems in young adult men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 29(3), 552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, Lewis M, Wang Y, Windle M, Kegler M, 2015. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Substance use & misuse 50(1), 79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, Levy NS, Santaella-Tenorio J, Hasin D, Wall MM, Keyes KM, Martins SS, 2020. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA psychiatry 77(2), 165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Wall M, Feng T, Keyes KM, Sarvet A, Schulenberg J, O’malley PM, Pacula RL, Galea S, Hasin DS, 2017. Association of state recreational marijuana laws with adolescent marijuana use. JAMA pediatrics 171(2), 142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D, 2012. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug and alcohol dependence 120(1–3), 22–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadi N, Schroeder R, Jensen JW, Levy S, 2019. Association between electronic cigarette use and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama Pediatrics 173(10), e192574–e192574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Frndak S, Lengua LJ, Read JP, Hawk LW, Wieczorek WF, 2018. Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior: A test of a latent variable interaction predicting a two-part growth model of adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 46(2), 319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, Silveira ML, Borek N, Kimmel HL, Sargent JD, Stanton CA, Lambert E, Hilmi N, 2018. Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among youth: findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addictive behaviors 76, 208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezenski L, 2020. Montana, Arizona, New Jersey, South Dakota and Mississippi approve marijuana ballot measures, CNN projects, CNN. CNN Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Wang Y, Emery SL, Chaloupka FJ, Kim Y, Huang J, 2021a. Exposure to e-cigarette TV advertisements among US youth and adults, 2013–2019. PloS one 16(5), e0251203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Wang Y, Huang J, 2021b. Sex Difference in the Association between Electronic Cigarette Use and Subsequent Cigarette Smoking among US Adolescents: Findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–4. International journal of environmental research and public health 18(4), 1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Veliz PT, Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, 2020. E-Cigarette and Cigarette Use Among US Adolescents: Longitudinal Associations With Marijuana Use and Perceptions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, 2009. School-based smoking prevention programs with the promise of long-term effects. Tobacco Induced Diseases 5(1), 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenman AP, Janssen TW, Oosterlaan J, 2017. Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 56(7), 556–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin JW, 2005. Generalized estimating equations (GEE). Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, Binns S, Vera LE, Kim Y, Szczypka G, Emery SL, 2019. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tobacco control 28(2), 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Lambert E, Carusi C, Taylor K, Crosse S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, 2017. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco control 26(4), 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, 2021. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975–2020: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. . [Google Scholar]

- Kalininskiy A, Bach CT, Nacca NE, Ginsberg G, Marraffa J, Navarette KA, McGraw MD, Croft DP, 2019. E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): case series and diagnostic approach. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 7(12), 1017–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Tang Z, Stanton CA, Sharma E, Halenar MJ, Taylor KA, Donaldson E, Hull LC, Day H, 2020. Correlates of tobacco product initiation among youth and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tobacco Control 29(Suppl 3), s191–s202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Briss PA, 2020. The EVALI and youth vaping epidemics—implications for public health. New England Journal of Medicine 382(8), 689–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KA, Merianos AL, Vidourek RA, 2016. Characteristics of marijuana acquisition among a national sample of adolescent users. American Journal of Health Education 47(3), 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ladegard K, Thurstone C, Rylander M, 2020. Marijuana legalization and youth. Pediatrics 145(Supplement 2), S165–S174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Ansary NS, 2005. Dimensions of adolescent rebellion: Risks for academic failure among high-and low-income youth. Development and psychopathology 17(1), 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Hanson K, Fleming CB, Ringle JL, Haggerty KP, 2015. Washington State recreational marijuana legalization: Parent and adolescent perceptions, knowledge, and discussions in a sample of low-income families. Substance use & misuse 50(5), 541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, 2017. Prevalence and attitudes regarding marijuana use among adolescents over the past decade. Pediatrics 140(6), e20170982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., Medicine, 2017. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. [PubMed]

- Nicksic NE, Do EK, Barnes AJ, 2020. Cannabis legalization, tobacco prevention policies, and Cannabis use in E-cigarettes among youth. Drug and alcohol dependence 206, 107730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH Alcohol Policy Information System, CANNABIS POLICY TOPICS - Recreational Use of Cannabis: Volume 1. https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/cannabis-policy-topics/recreational-use-of-cannabis-volume-1/104. (Accessed June 17 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MU, Thomsen KR, Heradstveit O, Skogen JC, Hesse M, Jones S, 2018. Externalizing behavior problems are related to substance use in adolescents across six samples from Nordic countries. European child & adolescent psychiatry 27(12), 1551–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehm KE, Young AS, Feder KA, Krawczyk N, Tormohlen KN, Pacek LR, Mojtabai R, Crum RM, 2019. Mental health problems and initiation of e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use. Pediatrics 144(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalco MD, Colder CR, Hawk LW Jr, Read JP, Wieczorek WF, Lengua LJ, 2014. Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and early adolescent substance use: A test of a latent variable interaction and conditional indirect effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 28(3), 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracqualursi V, 2019. Illinois becomes the 11th state to legalize recreational marijuana. CNN, Politics section; 25. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health & Human Services, 2016. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General.

- Wang GS, Davies SD, Halmo LS, Sass A, Mistry RD, 2018. Impact of marijuana legalization in Colorado on adolescent emergency and urgent care visits. Journal of Adolescent Health 63(2), 239–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA, 2020. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(37), 1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Chen X, Chen X, Yan H, 2020. Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health. BMC public health 20(1), 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.