Abstract

Abacavir (1592U89) {(−)-(1S, 4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol} is a 2′-deoxyguanosine analogue with potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1. To determine the metabolic profile, routes of elimination, and total recovery of abacavir and metabolites in humans, we undertook a phase I mass balance study in which six HIV-infected male volunteers ingested a single 600-mg oral dose of abacavir including 100 μCi of [14C]abacavir. The metabolic disposition of the drug was determined through analyses of whole-blood, plasma, urine, and stool samples, collected for a period of up to 10 days postdosing, and of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), collected up to 6 h postdosing. The radioactivity from abacavir and its two major metabolites, a 5′-carboxylate (2269W93) and a 5′-glucuronide (361W94), accounted for the majority (92%) of radioactivity detected in plasma. Virtually all of the administered dose of radioactivity (99%) was recovered, with 83% eliminated in urine and 16% eliminated in feces. Of the 83% radioactivity dose eliminated in the urine, 36% was identified as 361W94, 30% was identified as 2269W93, and 1.2% was identified as abacavir; the remaining 15.8% was attributed to numerous trace metabolites, of which <1% of the administered radioactivity was 1144U88, a minor metabolite. The peak concentration of abacavir in CSF ranged from 0.6 to 1.4 μg/ml, which is 8 to 20 times the mean 50% inhibitory concentration for HIV clinical isolates in vitro (0.07 μg/ml). In conclusion, the main route of elimination for oral abacavir in humans is metabolism, with <2% of a dose recovered in urine as unchanged drug. The main route of metabolite excretion is renal, with 83% of a dose recovered in urine. Two major metabolites, the 5′-carboxylate and the 5′-glucuronide, were identified in urine and, combined, accounted for 66% of the dose. Abacavir showed significant penetration into CSF.

The current recommendation for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is combination therapy with antiretroviral drugs with different modes of action, such as a protease inhibitor in combination with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (10). Problems with long-term antiretroviral therapy include (i) inadequate antiviral suppression and development of drug-resistant variants of HIV; (ii) adverse effects associated with drug toxicity, such as peripheral neuropathy, anemia, and lipodystrophy; and (iii) the failure of many antiretroviral drugs to penetrate the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and cross the blood-brain barrier, thus enabling the virus to replicate while sequestered in the central nervous system. Because toxicity and loss of efficacy due to viral drug resistance necessitate changes in drug regimens for HIV-infected patients, there is a continuing clinical need for new antiretroviral agents, ideally, agents with strong potencies, little or no cross-resistance to other antiretroviral agents, good safety and tolerability profiles, and adequate penetration into the CSF.

Abacavir (1592U89) is a 2′-deoxyguanosine analogue with potent activity against HIV type 1 (HIV-1). In vitro experiments with human T-lymphoblastoid CD4+ CEM cells have shown that abacavir is rapidly phosphorylated by a unique metabolic pathway to its active form, the triphosphate of the carbocyclic guanosine analogue (1144U88 triphosphate [1144U88-TP]), which is a potent inhibitor of viral reverse transcriptase (8). Preliminary data indicated that abacavir penetrates the CSF (7, 19), and in vitro experiments have shown abacavir to have potency against HIV strains resistant to other NRTIs (20).

Preclinical studies have shown that oral abacavir is primarily eliminated by hepatic metabolism to two major metabolites: 2269W93, a 5′-carboxylate formed by cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase, and 361W94, a 5′-glucuronide formed by uridine diphosphate glucuronyl transferase (11). In addition, 11 to 13% of oral abacavir is recovered as unchanged drug in urine (11). In vitro experiments have shown that clinically relevant concentrations of abacavir do not inhibit human liver CYP3A4, CYP2D6, or CYP2C9 activity and that abacavir is not significantly metabolized by human liver CYP450 enzymes (18).

In order to characterize in greater detail the metabolic profile of abacavir in humans, this phase I mass balance study (Glaxo Wellcome protocol CNAA-1003) was conducted with radiolabeled [14C]abacavir succinate administered as part of a single 600-mg oral abacavir dose to six HIV-infected volunteers. The purpose of this study was to determine the major metabolites of abacavir, describe pharmacokinetic parameters, estimate CSF penetration, and determine the routes of elimination for abacavir and its metabolites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This study was an open-label, mass balance, phase I trial conducted at a single study center, in which six HIV-infected male volunteers each received a single 600-mg oral dose of abacavir which contained 100 μCi of [14C]abacavir. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Radiation Safety/Radioactive Drug Research Committees at the Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, clinical study center, and the subjects provided written informed consent prior to study participation. The study consisted of a screening evaluation, a treatment phase with a single dosing period followed by a sample collection period of up to 10 days’ duration, and a follow-up evaluation. Laboratory and clinical assessments were performed at the screening evaluation, at check-in on the evening prior to dosing, and at the follow-up evaluation. Laboratory assessments included hematology, lymphocyte determination (screening only), clinical chemistry analysis, dipstick urinalysis, and urine screen for illicit drugs. Clinical assessments included physical examination, determination of vital signs, and electrocardiogram analysis. Subjects were monitored throughout the study for adverse experiences and for the use of concurrent medications and other restricted substances. The AIDS Clinical Trials Group toxicity grading scale was used for classification of abnormal laboratory values as adverse experiences.

Subjects were eligible for the study if they met the following criteria: were male; were 18 to 55 years of age; weighed from 55 to 95 kg, with a body mass index of 19 to 28 kg/m2; and were HIV seropositive with ≥200 CD4+ cells/mm3. In addition, the following exclusion criteria were applied: no current AIDS-defining conditions, no current treatment with protease inhibitors or non-NRTIs; no current treatment with medications which could not be withheld for 24 h (for antiretroviral or prophylactic agents) or for 48 h (for other, nonessential medications) prior to dosing until the end of the sample collection period; no current use of illicit drugs; no history of clinically relevant hepatitis or pancreatitis within the previous 6 months; no clinically significant neurological abnormality; absence of specified laboratory abnormalities; no clinically significant history of systemic illness of dysfunction which, in the opinion of the investigator, might have compromised the safety of the subject; and no exposure to excess radiation or participation in a study involving radioisotopes within the previous 12 months.

The subjects were required to fast (water was permitted) for a minimum of 8 h prior to dosing. At approximately 4 and 10 h postdosing the subjects were served a standard lunch and dinner, respectively. The subjects were given standard meals three times a day on subsequent study days and were encouraged to drink water and other liquids as needed.

Materials.

The investigational drug was a mixture of radiolabeled [14C]abacavir succinate and unlabeled [12C]abacavir succinate powders, prepared by the Division of Bioanalysis and Drug Metabolism, Glaxo Wellcome, Inc. Radiolabeled drug was synthesized by the Chemical Development Division, Glaxo Wellcome, Inc. Drug was supplied in individual bottles containing 700 mg (base equivalent) of preweighed powder, comprising a nominal 0.82 mg (base equivalent) of [14C]abacavir and 699.18 mg (base equivalent) of abacavir. The batch number, specific activity, chemical purity, and radiochemical purity of [14C]abacavir were R675/136/1, 127 μCi/mg, 98.3%, and 99.6%, respectively. The batch number of abacavir succinate used in this study was 5X3226, and its chemical purity was approximately 98.1%.

Dosing.

For dose preparation for each subject, 70 ml of sterile water for irrigation was added to the bottle containing the 700-mg mixture of [14C]abacavir succinate and [12C]abacavir succinate powders. The mixture was gently swirled and was then sonicated for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath to ensure complete dissolution of the powder before removal of exactly 10 ml of solution. One 5-ml aliquot was used for liquid scintillation counting, to verify the amount of radioactivity in the solution prior to administration of the dose to the subject. The other 5-ml aliquot was stored in a non-self-defrosting freezer set at −20°C or lower prior to shipment to Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., for analysis of the actual concentrations of abacavir. The radioactivity contained in a 60-ml dose ranged from 87 to 91 μCi. The subject ingested the solution under the supervision of study site personnel. The bottle was rinsed twice with 50 ml of sterile water for irrigation, and the subject ingested both rinses.

Sample collections.

Samples that were collected included urine and stool specimens, plasma and whole-blood samples, and CSF samples. Stool and urine specimens were collected for a minimum 4-day period, up to 10 days postdosing. For both urine and stool specimens, collection continued (i) until 10 days postdosing or (ii) until radioactivity levels in specimens from two consecutive collection intervals were ≤1% of the administered dose, whichever occurred first.

Urine was collected starting 15 min prior to dosing, to establish a baseline, and thereafter over the following intervals: 0 to 4, 4 to 8, 8 to 12, 12 to 24, 24 to 48, 48 to 72, and 72 to 96 h postdosing and for each subsequent 24-h period until collection was discontinued as described above. From each specimen collection, 10-ml portions were transferred to each of three prelabeled, 13-ml plastic polypropylene tubes. One tube was used immediately for liquid scintillation counting, and the other two tubes were stored in a non-self-defrosting freezer set at approximately −20°C prior to shipment to Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., for analysis.

Stools were collected starting with a predose specimen (if available) and thereafter over the following intervals: 0 to 24, 24 to 48, 48 to 72, and 72 to 96 h postdosing and for each subsequent 24-h period until discontinuation as described above. After weighing, the stool sample was homogenized in deionized water (volume of water equivalent to four times the weight of the stool sample) with a model PT3000 Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instrument Co., Westbury, N.Y.). Triplicate portions of the homogenate were removed for liquid scintillation counting, and a portion of the homogenate was transferred to a 120-ml plastic bottle and stored in a non-self-defrosting freezer set at approximately −20°C prior to shipment to Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., for analysis.

Plasma and whole-blood samples were collected for a minimum 2-day period. At each sampling time, 9 ml of blood was drawn into a syringe with a peripheral venous catheter. For radioactivity determination, a portion of the blood (1.0 to 1.5 ml) was immediately transferred to a prelabeled, 5-ml, heparinized plastic tube. The remaining blood was injected into two prelabeled, 4-ml, dipotassium EDTA-containing VACUTAINER brand blood collection tubes, which were centrifuged for separation of plasma. A portion (1 to 1.5 ml) of the plasma was taken for liquid scintillation counting, and the remaining plasma was transferred to prelabeled, 4-ml plastic tubes and stored in a non-self-defrosting freezer set at approximately −20°C or lower prior to shipment to Glaxo Wellcome Inc., for analysis. After samples had been drawn for the first 48 h, plasma and whole blood-sample collections were discontinued when one of the following occurred: (i) assays indicated that radioactivity levels had decreased to less than or equal to twice the level of background radioactivity (∼30 dpm) in two consecutive samples or (ii) the stool and urine specimen collections were discontinued. Plasma and whole-blood samples were taken starting 5 min prior to dosing, to establish a baseline, and thereafter at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, 36, and 48 h postdosing. If the radioactivity levels in the samples retrieved at 36 and 48 h were each less than or equal to twice the background radioactivity level, then sample collection was discontinued; otherwise, sample collection was continued at 12-h intervals up to 240 h postdosing, until a criterion for discontinuation was met.

CSF samples were collected only on day 1. Three subjects who could be catheterized received an indwelling lumbar catheter. A predose sample was drawn when the catheter was inserted, with additional samples drawn at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2.5, 4, and 6 h postdosing. Subjects were encouraged to remain semisupine from the time of catheterization until at least 1 h after the lumbar catheter was removed. To prevent dehydration, subjects were encouraged to drink 240 ml of water every 30 min. After retrieval of the sample at 6 h postdosing, the lumbar catheter was removed.

Determination of total [14C]radioactivity.

Samples were assayed with scintillation counters (models 4530 and 2100TR; Packard Instrument Co., Meridan, Conn.) at the Bioanalytical Analysis Laboratory of the Department of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutics, Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. Total 14C radioactivity was determined for dosing solutions prior to dosing of the subjects and for blood, plasma, CSF, stool, and urine samples throughout the study. The radioactivity was measured with triplicate aliquots for each sample by scintillation counting either for 10 min or until a 1% deviation was obtained. The radioactivity in the dosing solution, plasma, CSF, and urine samples was measured directly with Insta-Gel XF scintillation cocktail (Packard Instrument Co.); whole-blood and stool samples were assayed for radioactivity following combustion. Triplicate 0.25-ml blood samples were dried on absorption pads and were prepared for analysis by combustion in a sample oxidizer (model 306; Packard Instrument Co.) with 0.25 ml of Combustaid for 35 s (combustion cones, absorption pads, and Combustaid were from Packard Instrument Co.). Triple aliquots of 0.80 to 0.95 g of fecal homogenate were dried and were prepared similarly, with combustion for 45 s. After combustion, the resulting carbon dioxide was trapped with 10 ml of a CO2 fixer (Carbo-Sorb; Packard Instrument Co.) and was mixed with 10 ml of scintillation cocktail (Permafluor; Packard Instrument Co.).

Radiochemical profiling of urine and feces.

Assays were performed with urine samples with detectable radiation and with fecal extracts with radioactivity >5% of the administered dose. Samples were assayed by the Division of Bioanalysis and Drug Metabolism, Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., with a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters Discovery HPLC System; Waters Inc., Milford, Mass.) with an on-line radiochemical detector (model LB 507A; Berthold, Wildbad, Germany). The HPLC system used a Kromasil octadecyl column (Phenomenex, Torrance, Calif.) at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min, and the mobile phase was 25 mM ammonium acetate (pH 4.0)–methanol (95:5) with a linear acetonitrile gradient from 0 to 13% over 50 min. Fecal samples were extracted with methanol-water (3:1) prior to injection. The following analytical standards were injected: [14C]abacavir, abacavir, major metabolites 2269W93 and 361W94, and minor metabolites 1144U88 and 139U91. The range of the assay was 0.64 to 56.6 μg/ml for abacavir, 0.27 to 24.5 μg/ml for 2269W93, and 0.56 to 52.1 μg/ml for 361W94 in urine. Accuracy, expressed as mean percent difference from the nominal value, was demonstrated to be within 10% for abacavir and 2269W93 and within 3% for 361W94. Precision, expressed as a maximum coefficient of variation (CV), was demonstrated to be <10% for abacavir, <7% for 2269W93, and <8% for 361W94.

In profiling the urine and fecal samples, the percentage of the dose attributable to each chromatographic peak was estimated by using the total radioactivity data for each sample, as calculated by the Bioanalytical Analysis Laboratory at the Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University. The percentage of the administered dose attributable to each recovered analyte in each sample was estimated as [(peak chromatographic heightsample/sum total of peak heightssample) × percentage of dose in sample] × 100.

Quantification of abacavir and metabolites.

CSF, plasma, and urine samples were analyzed by the Division of Bioanalysis and Drug Metabolism, Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., by a validated HPLC method with UV detection at 295 nm for abacavir, 2269W93, and 361W94. The plasma samples were assayed over a quantifiable range of 25 to 5,000 ng/ml. The HPLC system and octadecyl column were identical to those used for radiochemical profiling, but the mobile phase was 25 mM ammonium acetate (pH 4.0)–methanol (95:5) with a linear methanol gradient from 0 to 50% over 30 min. For each analysis, calibration standards and quality control samples were included. Accuracy was demonstrated to be within 3% for abacavir, 6% for 2269W93, and 7% for 361W94. Precision (percent CV) was demonstrated to be <8% for abacavir and 2269W93 and <7% for 361W94. Because the study subjects were HIV positive, the samples were heated for 5 h at 58°C to inactivate virus prior to sample analysis. Following heat inactivation of HIV, the stabilities of abacavir and its metabolites were also assessed. Accuracy was demonstrated to be within 7% and precision (percent CV) was determined to be within 2% for all analytes.

CSF samples were injected directly into the HPLC system for analysis. For plasma sample analysis, sample protein was first removed by methanol precipitation prior to injection. The range of the assay was 0.06 to 5.13 μg/ml for abacavir, 0.06 to 5.10 μg/ml for 2269W93, and 0.06 to 5.13 μg/ml for 361W94 in CSF. Accuracy was demonstrated to be within 14% for abacavir, 9% for 2269W93, and 7% for 361W94. Precision (percent CV) was demonstrated to be <7% for abacavir, 2269W93, and 361W94.

Urine samples were centrifuged to minimize particulates, and the supernatant was diluted 1:10 with the HPLC mobile phase prior to injection into the HPLC system. The range of the assay was 0.64 to 56.6 μg/ml for abacavir, 0.27 to 24.5 μg/ml for 2269W93, and 0.56 to 52.1 μg/ml for 361W94 in urine. Accuracy was demonstrated to be within 6% for abacavir, 10% for 2269W93, and 3% for 361W94. Precision (percent CV) was demonstrated to be <10% for abacavir, <7% for 2269W93, and <8% for 361W94. Following heat inactivation of HIV, the stabilities of abacavir and its metabolites were also assessed. Accuracy was demonstrated to be within 3% and precision was demonstrated to be <4% for all analytes.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed by Worldwide Clinical Pharmacology, Glaxo Wellcome, Inc. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from plasma and CSF concentration-time data for abacavir, 2269W93, and 361W94 and from blood, plasma, and CSF radioactivity-time data by standard noncompartmental methodologies. The WinNonlin Noncompartmental Analysis Program, version 1.5 (Scientific Consulting, Inc., Cary, N.C.), with model 200 for oral input was used for data analyses.

The following parameters were derived for each subject: maximum measured concentration (Cmax), sample time associated with Cmax (Tmax), terminal elimination rate constant (λz) and the corresponding terminal half-life (t1/2), area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) from time zero to the last quantifiable concentration (AUClast), area under the concentration-time curve extrapolated to infinite time (AUC0–∞), calculated as AUC0–∞ = AUClast + Clast/λz (where Clast is the last measurable drug concentration), and percentage of AUC0–∞ extrapolated, calculated as 100 · (AUC0–∞ − AUClast)/AUC0–∞.

AUC estimates were calculated by the log-linear trapezoidal rule. Calculations of the penetration of abacavir into the CSF were based on comparisons of the AUC0–∞ for CSF to the AUC0–∞ for plasma, as described previously (14). For presentation of data comparing pharmacokinetic parameters of abacavir and the two major metabolites, metabolite concentrations were converted to abacavir equivalents, based on the following molecular weights: abacavir, 286.34; 2269W93, 300.32; and 361W94, 462.46.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics.

Six male HIV-seropositive subjects were enrolled in the study, and all subjects completed the study. The median age was 36.5 years (range, 31 to 47 years), the median weight was 74.25 kg (range, 59.4 to 112.6 kg), and the median height was 174.0 cm (range, 170.0 to 183.0 cm). Five subjects were black and one subject was white; four were in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV classification category A (asymptomatic), and two were in category C (AIDS) (4). The median absolute CD4+ lymphocyte count was 478 cells/mm3 (range, 234 to 924 cells/mm3) and the median absolute CD8+ cell count was 654 cells/mm3 (range, 402 to 1,324 cells/mm3). Three subjects were enrolled at the discretion of the investigator, despite positive results of urine screens for illicit drug use (cannabis and cocaine) at screening or on the evening prior to study drug administration. These drugs were thought to be unlikely to affect the results of the study.

Pharmacokinetic parameter evaluations of plasma and CSF.

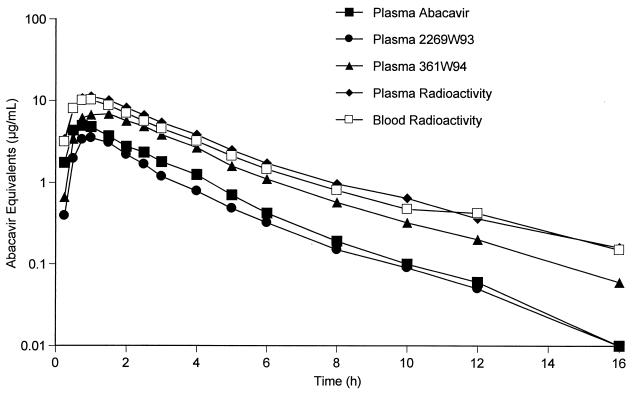

HPLC analysis detected abacavir and its two major metabolites, 2269W93 and 391W94, in plasma from all six subjects, beginning with the first sample drawn at 0.25 h postdosing. Figure 1 shows a semilogarithmic plot of the concentrations in plasma of abacavir and its two major metabolites, expressed as abacavir equivalents, for the first 16 h postdosing.

FIG. 1.

Mean abacavir, 2269W93, and 361W94 plasma concentrations and measured radioactivity in plasma and blood for all six subjects. The concentrations of 2269W93 and 361W94 are expressed as abacavir equivalents.

Summary data for the pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 1. For both metabolites, the geometric means of the t1/2 estimates for the two metabolites, 2.19 h for 2269W93 and 2.78 h for 361W94, were similar to that for the parent compound, 2.10 h for abacavir. As shown in Table 1, the geometric mean AUC0–∞ for abacavir was 12.81 μg · h/ml, and the geometric mean AUC0–∞ values, converted to abacavir equivalents, for 2269W93 and 361W94 were 8.80 and 15.27 μg · h/ml, respectively. The corresponding geometric mean ratios of AUC0–∼ for 2269W93 and 361W94 metabolites to that for abacavir (in abacavir equivalents) were calculated as 0.69 and 1.19, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for abacavir and its two major metabolites following administration of a single oral dose of 600 mg of abacavir in plasmaa

| Drug or metabolite (sample matrix) | AUC0–∞ (μg · h/ml) | Cmax (μg/ml) | t1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir (plasma) | 12.81 (8.66–18.96) | 5.46 (4.32–6.91) | 2.10 (1.02–4.34) | 0.74 (0.50–1.00) |

| 2269W93 (plasma) | 9.23 [8.80]b (7.22–11.81) | 3.72 (2.86–4.84) | 2.19 (1.31–3.68) | 1.00 (0.75–1.53) |

| 361W94 (plasma) | 24.66 [15.27] (20.11–30.23) | 7.22 (5.95–8.76) | 2.78 (1.93–3.99) | 1.25 (0.75–1.53) |

| Abacavir (CSF) | 5.14 (2.01–13.13) | 1.02 (0.52–1.98) | 2.32 (1.46–3.67) | 2.48 (1.50–2.50) |

Values are geometric means (95% confidence intervals) for AUC0–∞, Cmax, and t1/2. Values are medians (ranges) for Tmax. Six plasma samples and three CSF samples were tested.

Values in brackets are calculated as abacavir equivalents by using the following molecular weights: abacavir, 286.34; 2269W93, 300.32; and 361W94, 462.46.

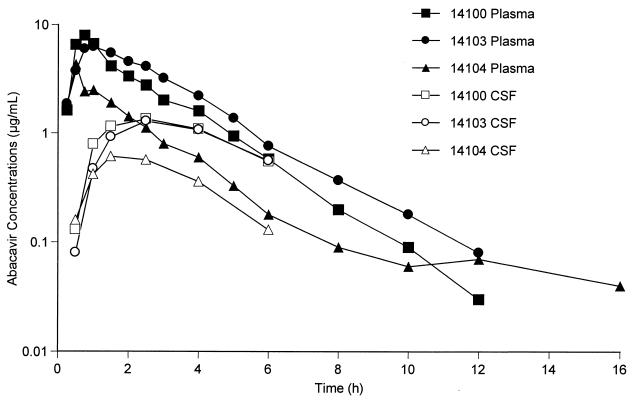

In contrast to the results for plasma, there were no quantifiable concentrations of 2269W93 in any CSF samples from the subjects who participated in the CSF substudy. Very low but quantifiable concentrations of 361W94 were present in only three CSF samples, all from the same subject. Figure 2 shows a semilogarithmic plot of the concentrations of abacavir in CSF and plasma, which were quantifiable in all three subjects from whom samples were obtained. Cmax values of abacavir in CSF ranged from 0.6 to 1.4 μg/ml (or ∼2 to 5 μM). The median Tmax for abacavir in CSF occurred more than 1 h later in CSF (2.48 h) than in plasma (0.74 h) (Table 1). The median ratio of abacavir penetration into CSF was 35% (range, 31 to 44% [n = 3]). When the median ratio of abacavir penetration into CSF was calculated on the basis of the AUC from 0 to 6 h postdosing for plasma and CSF, the ratio was 31% (range, 27 to 34%).

FIG. 2.

Individual abacavir concentrations measured in CSF and plasma for subjects 14100, 14103, and 14104.

Recovery of abacavir and metabolites in urine.

A summary of the amounts (in milligrams) and percentages of drug recovered in urine is shown in Table 2. Recovery of abacavir in urine was low, with no measurable amounts detected in two subjects (subjects 14102 and 14104). Measurable levels of both 2269W93 and 361W94 were recovered from all six subjects, and the median percentage of drug recovered as these three analytes was 46.26% of the administered dose.

TABLE 2.

Recovery of abacavir, 2269W93, and 361W94 in urinea

| Drug or metabolite | Amt (mg) | % Dose recovered |

|---|---|---|

| Abacavir (n = 4) | 11.65 (8.85–14.91) | 1.94 (1.48–2.49) |

| 2269W93 (n = 6) | 139.71 (119.77–171.00) | 22.20 (19.03–27.17) |

| 361W94 (n = 6) | 229.82 (184.70–283.26) | 23.72 (19.06–29.23) |

| Total recovery | 46.26 (40.35–58.48) |

Values are medians (ranges).

Pharmacokinetic evaluation of radioactivity.

Summary pharmacokinetic data derived from assays of radioactivity in plasma, blood, and CSF samples are shown in Table 3. Data are presented as abacavir equivalents. Measurements in whole blood are consistent with equivalent measurements in plasma, with blood-to-plasma geometric mean ratios of 97% for AUC0–∞ and of 93% for Cmax. Tmax and t1/2 values are consistent between whole blood and plasma, with overlap in the 95% confidence interval.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters as abacavir equivalents determined from radioactivity in blood, plasma, and CSFa

| Sample matrix | AUC0–∞ (μg · h/ml) | Cmax (μg/ml) | t1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood (n = 6) | 38.86 (30.01–50.32) | 10.95 (8.56–14.01) | 5.50 (3.24–9.35) | 0.88 (0.50–1.00) |

| Plasma (n = 6) | 40.10 (33.04–48.67) | 11.78 (9.63–14.42) | 3.26 (2.03–5.25) | 0.88 (0.50–1.53) |

| CSF (n = 3) | 6.87 (3.50–13.51) | 1.04 (0.58–1.86) | 3.49 (2.99–4.08) | 2.50 (2.48–2.50) |

Values are geometric means (95% confidence intervals) for AUC0–∞, Cmax, and t1/2. Values are medians (ranges) for Tmax.

Calculation of the percentage of radioactivity in plasma comprising the radioactivities of abacavir and its two major metabolites was based on comparison of the total geometric mean AUC0–∞ in abacavir equivalents derived from HPLC analysis (36.88 μg · h/ml) (Table 1) to the total geometric mean AUC0–∞ in abacavir equivalents derived from radioactivity measurements (40.10 μg · h/ml) (Table 3). On the basis of this ratio, the radioactivities of abacavir and its two major metabolites comprised 92% of the radioactivity assayed in plasma.

The mean AUC0–∞ for abacavir in CSF determined by HPLC was estimated to be 5.14 μg · h/ml (Table 1) and is 75% of the mean AUC0–∞ determined from radioactivity measurements, estimated to be 6.87 μg · h/ml (Table 3). Mean Cmax and median Tmax estimates for abacavir in CSF were consistent between HPLC (Table 1) and radioactivity measurements (Table 3). Cmax values for abacavir in CSF ranged from 0.7 to 1.4 μg/ml (or ∼2 to 5 μM). However, there are differences in t1/2 estimates, with the t1/2 estimate from total radioactivity measurements (3.49 h) being approximately 1 h longer than the t1/2 estimate for abacavir (2.32 h).

Radioactivity in urine and stool.

Virtually all administered radioactivity was recovered during the study, with 83% recovered in urine and 16% recovered in feces (Table 4). After the first 48 h, no urine sample collected from any subject contained ≥1% of the radioactivity in the dose administered to that subject. After 6 days (144 h), no stool samples collected from any subjects contained ≥2% of the radioactivity in the administered dose, with most of the recovered radioactivity being collected from each subject within the first 4 days (96 h).

TABLE 4.

Summary of mean dose and mean recovery of radioactivity from urine and fecesa

| Sample | Amt of radioactivity (μCi) | Radioactivity as % of dose |

|---|---|---|

| Administered doseb | 89.12 (87.15–91.25) | |

| Urinec | 74.07 (69.16–79.33) | 83.13 (78.01–88.59) |

| Fecesc | 14.25 (12.36–16.44) | 15.99 (13.79–18.54) |

| Totalc | 88.44 (83.09–94.13) | 99.25 (93.50–105.36) |

Urine and fecal samples from six patients were tested.

Values are arithmetic means (ranges).

Values are geometric means (95% confidence intervals).

Radiochemical profiling of urine and feces.

All analyte radioactivity comprising greater than 2% of the administered radioactivity was identified by radiochemical profiling of urine and feces. The only analytes in urine comprising greater than 2% of the administered dose, as determined by radiochemical profiling, were the two major metabolites of abacavir: 2269W93 accounted for 29.7% and 361W94 accounted for 35.8%. Abacavir accounted for 1.2% of the administered dose, 1144U88 accounted for 0.6%, and 1.7% was not accounted for. Thus, a total of 69% of the administered dose was detected by urine profiling, which also identified 67.3% of the administered dose. The difference between urinary recovery results detected by radioactivity measurements (83.1%) and those identified by radiochemical profiling (67.3%) indicates that approximately 15.8% of the radioactivity has not been identified and may be attributable to numerous minor metabolites, each of which accounted for <2% of the dose.

Radioactivity profiling of feces, based upon the only three samples which contained >5% of the administered radioactivity, showed a major peak identified by retention time as 2269W93. Minor peaks identified as abacavir and 1144U88 were present as trace components. No 361W94 was detected in feces.

Safety.

There were no serious adverse experiences reported during the study. Subjects reported a total of 26 adverse experiences during the study, only 1 of which, a single episode of nausea, was considered possibly attributable to the study drug. One subject experienced an adverse experience (back pain) graded as severe; all other adverse experiences were reported as mild (10 events) or moderate (1 event) or were graded in severity as AIDS Clinical Trials Group toxicity grade 1 (11 events) or grade 2 (3 events). All adverse experiences resolved prior to study completion. There were no consistent changes or abnormalities in clinical chemistry, hematology, or urinalysis parameters.

DISCUSSION

This study provides a definitive analysis of abacavir metabolism and elimination in humans and gives the first quantitation of the two major abacavir metabolites in plasma by a validated assay. The majority of radioactivity detected in plasma (92%) was attributed to abacavir and its two major metabolites, 2269W93 and 361W94. The metabolite profiles seen in human urine described in this study are consistent with the profiles observed in preclinical studies (12). The majority of radioactivity identified by urine profiling comprised a mixture of the radioactivity from abacavir and its two major metabolites, leaving only 15.8% as the radioactivity from unidentified minor metabolites, each with <2% of the administered radioactivity. This study demonstrated that abacavir has significant CSF penetration, with the median ratio of the AUC0–∞ for CSF to the AUC0–∞ for plasma being 35% of total drug. Finally, a single 600-mg oral dose of radiolabeled abacavir was well tolerated by all study subjects, with no new safety concerns raised during the conduct of this study. The majority of adverse experiences reported were associated with the lumbar puncture procedure, and only a single episode of nausea was considered possibly attributable to the study drug.

Pharmacokinetic studies show a wide range of oral bioavailabilities among different NRTIs. For example, oral bioavailabilities are 20 to 40% for didanosine (9), 60% for zidovudine (23), and 80% or greater for zalcitabine (1), stavudine (17), and lamivudine (15). In the present study, the extent of absorption following administration of a single oral dose of 600 mg of abacavir was at least 83% since that percentage of the administered radioactivity was recovered in the urine. This finding is consistent with results from an earlier study estimating 83% absolute bioavailability following administration of a 300-mg oral dose of abacavir (5). The pharmacokinetic parameters estimated in this study were generally consistent with estimates from similar studies in which an equivalent 600-mg dose was administered in solid tablet form rather than in oral solution form (13, 21). As expected, the Cmax estimate from the oral solution used in this study tended to be slightly higher than the Cmax estimates from the solid dosage forms used in previous studies.

Penetration of CSF is a critically important factor in antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection, as HIV can continue to replicate sequestered in central nervous system compartments, despite evidence of an antiviral response in plasma (6, 22). Our results indicate that the Cmax of abacavir in CSF (0.6 to 1.4 μg/ml) was 8 to 20 times the mean 50% inhibitory concentration for HIV clinical isolates in vitro (0.07 μg/ml), indicating significant penetration into the CSF. Our results also suggest that very little metabolism of abacavir occurs in the CSF and that the metabolites have limited penetration into the CSF. The estimate of CSF penetration (31 to 44%) in this report is higher than that reported previously probably because of the multiple points used for analysis. Ravitch et al. (19) reported CSF/plasma concentration ratios of 18% (range, 12 to 24%) at 1.5 to 2 h postdosing after administration of abacavir at 200 mg three times daily to HIV-infected patients (19). Since both drug entry and drug elimination are slower in CSF than in plasma (14; this study), calculations of penetration into CSF based upon simultaneous sampling of plasma and CSF tend to be inaccurate. Burger et al. (3) have demonstrated that time after zidovudine administration strongly influenced the calculated CSF/plasma concentration ratio. A more robust method, such as the one used in the study described in this report, is to describe the ratio of AUC0–∞ for CSF to the AUC0–∞ for plasma, since this parameter is independent of the kinetics of exchange between the body compartments (14). Calculations by this method gave a median estimate of 35% CSF penetration. As 50% of abacavir is protein bound (2a) and only unbound abacavir is available for CSF penetration, it follows that 70% of the unbound drug is able to penetrate into the CSF.

Results of the current study indicate that concentrations of abacavir in CSF (Cmax) are above the in vitro 50% inhibitory concentration reported previously (7), similar to reports for most other NRTIs (16). As a pharmacologic class, NRTIs have superior CSF penetration compared with the penetration of protease inhibitors and are widely variable in the degree to which they penetrate, with CSF/plasma concentration ratios ranging from 20% for zalcitabine to 60% for zidovudine (2). Thus, results from the present study indicate that abacavir compares favorably with other NRTIs in terms of CSF penetration (35%) and CSF drug concentrations.

Several reasons are likely to account for the difference noted in the amount of radioactivity in urine measured by scintillation counting versus the amount determined by radiochemical profiling. First, the volumes of urine produced by most subjects over the course of the study were somewhat higher than would normally be expected, but volumes for two subjects (subjects 14103 and 14104) over the first 24 h were very high (6.33 and 9.20 liters, respectively). The majority of samples for these subjects were much more dilute than would normally be expected for the collection intervals, resulting in most samples having less radioactivity than could be detected consistently by the on-line radiochemical detector. Second, radiochemical profiling can consistently identify only individual analytes that are greater than 2% of the dose in each radiochromatogram. As each sample contained multiple abacavir analytes, radioactivity in samples obtained after 8 h postdosing generally could not be profiled.

In summary, results from this study support previous evidence indicating that abacavir is well tolerated, that it has a high degree of oral bioavailability, that abacavir is metabolized to two primary metabolites, and that abacavir penetrates into the CSF effectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Yu Lou for statistical consultations, Veronica Parker for database management, Clark March for assistance with radioactivity studies, Michael O’Mara for assistance with plasma bioanalytical studies, and Belinda Ha and Barbara Rutledge for manuscript and writing assistance. We also thank the staff at Virginia Commonwealth University, in particular, Donna Francioni-Proffitt, Abraham Enfiedjian, Rajeev Menon, Varsa Natarajan, Ronald Lees, Linda Brown-Burton, and H. Thomas Karnes, for assistance in the conduct of the study.

This study was supported by a grant from Glaxo Wellcome, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins J C, Peters D H, Faulds D. Zalcitabine: an update of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy in the management of HIV infection. Drugs. 1997;53:1054–1080. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beach J W. Chemotherapeutic agents for human immunodeficiency virus infection: mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and adverse reactions. Clin Ther. 1998;20:2–25. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Bulkowski D, Wargin W. Protein binding of 1592U89 in human, monkey, and mouse plasma (PDM043). Document TBZZ/93/0010, 22 February. Triangle Park, N.C: Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger D M, Kraaijeveld C L, Meenhorst P L, Mulder J W, Koks C H W, Bult A, Beijnen J H. Penetration of zidovudine into the cerebrospinal fluid of patients infected with HIV. AIDS. 1993;7:1581–1587. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded case surveillance definition in adolescents and adults. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1992;41(51):961–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chittick, G. E., C. Gillotin, J. A. McDowell, Y. Lou, K. D. Edwards, W. T. Prince, and D. S. Stein. Abacavir (1592U89): absolute bioavailability, bioequivalence of three oral formulations, and effect of food. Pharmacotherapy 19:932–942. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Chun T W, Stuyver L, Mizell S B, Ehler L A, Mican J M, Baseler M, Lloyd A L, Nowak M A, Fauci A S. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13193–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daluge S M, Good S S, Faletto M B, Miller W H, St. Clair M H, Boone L R, Tisdale M, Parry N R, Reardon J E, Dornsife R E, Averett D R, Krenitsky T A. 1592U89, a novel carbocyclic nucleoside analog with potent, selective, anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1082–1093. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faletto M B, Miller W H, Garvey E P, St. Clair M H, Daluge S M, Good S S. Unique intracellular activation of the potent anti-human immunodeficiency virus agent 1592U89. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1099–1107. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faulds D, Brogden R N. Didanosine: a review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Drugs. 1992;44:94–116. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199244010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg M B, Carpenter C, Fauci A S, Stanley S K, Cohen O, Bartlett J G, Kaplan J E, Abrutyn E. Report of the NIH panel to define principles of therapy of HIV infection and guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:1057–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Good S S, Daluge S M, Ching S V, Ayers M M, Mahony W B, Falletto M B, Domin B A, Owens B S, Dornsife R E, McDowell J A, LaFon S W, Symonds W T. 1592U89 succinate-preclinical toxicological and disposition studies and preliminary clinical pharmacokinetics. Antivir Res. 1995;26:A229. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Good S S, Owens B X, Faletto M B, Mahony W B, Domin B A. Program and abstracts of the 34th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. Disposition in monkeys and mice of (1S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol (1592U89) succinate, a potent inhibitor of HIV, abstr. I86; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar P N, Sweet D E, McDowell J A, Symonds W, Lou Y, Hetherington S, LaFon S. Safety and pharmacokinetics of abacavir (1592U89) following oral administration of escalating single doses in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:603–608. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nau R, Zysk G, Thiel A, Prange H W. Pharmacokinetic quantification of the exchange of drugs between blood and cerebrospinal fluid in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;45:469–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00315520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry C M, Faulds D. Lamivudine: a review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of HIV infection. Drugs. 1997;53:657–680. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portegies P, Rosenberg N R. AIDS dementia complex: diagnosis and drug treatment options. CNS Drugs. 1998;9:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rana K Z, Dudley M N. Clinical pharmacokinetics of stavudine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:276–284. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravitch J R, Bryant B J, Reese M J, Boehlert C C, Walsh J S, McDowell J P, Sadler B M. Abstracts of the 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Chicago, Ill: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 1998. In vivo and in vitro studies of the potential for drug interactions involving the antiretroviral 1592 in humans, abstr. 634; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravitch J R, Jarrett J L, Robertson W H, Polli J W, Humphreys J E, Good S S. Abstracts of the 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Chicago, Ill: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 1998. CNS penetration of the anti-retroviral 1592 in human and animal models, abstr. 636; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tisdale M, Alnadaf T, Cousens D. Combination of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase required for resistance to the carbocyclic nucleoside 1592U89. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1093–1098. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, L. H., G. E. Chittick, and J. A. McDowell. Single-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of abacavir (1592U89), zidovudine, and lamivudine administered alone and in combination in adults with HIV infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1708–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Wong J K, Hezareh M, Gunthard H F, Havlir D V, Ignacio C C, Spina C A, Richman D D. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Myers C E, Broder S. Clinical pharmacology of 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine) and related dideoxynucleosides. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:726–738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909143211106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]