Abstract

Objectives:

This article assessed whether disparities among ADRD Medicare beneficiaries existed in five different long-stay quality measures.

Methods:

We linked individual-level data and facility-level characteristics. The main quality outcomes included whether residents: 1) were assessed/appropriately given the seasonal influenza vaccine; 2) received an antipsychotic medication; 3) experienced one/more falls with major injury; 4) were physically restrained; and 5) lost too much weight.

Results:

In 2016, there were 1,005,781 Medicare Advantage and fee-for-service long-term residents. About 78% were White, 13% Black, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander (Asian/PI), 6% Hispanic, and 0.4% American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN). Whites reported higher use of antipsychotic medications along with Hispanics and AI/AN (28%, 28%, and 27%, respectively). Similarly, Whites and AIs/ANs reported having one/more falls compared to the other groups (9% and 8%, respectively).

Discussion:

Efforts to understand disparities in access and quality of care among American Indians/Alaska Natives are needed, especially post-pandemic.

Keywords: quality of care among people with dementia, long-term residents with dementia, quality among American Indians and Alaska Natives

Introduction

In the United States, close to six million older adults have Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019b), and this number is only expected to increase three-fold by 2060 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). In a country with striking socio-economic and health disparities (Hooper et al., 2020), the burden of ADRD may carry additional consequences not only for patients but also for family members and caregivers as well. There are disparities in the incidence of ADRD among racial and ethnic groups (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Incidence of ADRD is higher among Black and American Indian/Alaska Native patients and intermediate for Hispanic and Pacific Islander patients (Mayeda et al., 2016). These groups are largely affected due to the high prevalence of comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Furthermore, these vulnerable groups may be more likely to live in more polluted areas and suffer racism and discrimination (Gong et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2014). The ability to live independently and perform activities of daily living (ADLs) may be threatened as ADRD progresses. Furthermore, people with ADRD have higher mortality rates and burdensome transitions compared to non-ADRD patients (Gozalo et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2015; Mor et al., 2010; Teno et al., 2013). ADRD brings different and complex challenges to families and providers (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2020). However, supportive services may not be easily accessible among racial and ethnic groups (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Families may need to become caregivers or to seek long-term services and support for the patient, and people with ADRD may be placed in nursing homes. In fact, about 50% of long-term care residents have ADRD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Nursing home care is one of the most expensive components of ADRD care, which ranges between $130 and $340 per day (Dementia Care Central, 2019). The proportion of minority elders going to nursing homes has increased steadily in the past decades, partially due to demographic changes and disparities in long-term care alternatives (Feng et al., 2011). The high concentration of individuals with ADRD in nursing homes suggests an urgency to understand the quality of care and outcomes among this population and whether differences by race and ethnicity exist.

Many people with ADRD do not have access to high-quality care (Larson & Stroud, 2021). Thus, eliminating these disparities is a high priority in the US health care agenda (US Department of Health and Human Services; Office of the Inspector General, 2015). However, in terms of dementia care, the primary focus has been on reducing antipsychotic use in nursing homes (Lucas & Bowblis, 2017). The purpose of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Nursing Home quality Initiative is to provide consumers and/or family members reliable information needed to make appropriate choices about nursing home care (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021b). Thus, CMS tracks multiple indicators that are used to assess nursing home quality including structural, process, and outcome measures (Castle & Ferguson, 2010). However, these measures are reported for all residents regardless of ADRD status. Family members and/or caregivers using Nursing Home Compare or other publicly available information to select nursing homes are unable to filter out or select facilities that may provide quality and equitable care for people with ADRD. There are no data about how minority residents with ADRD fare on some of these measures. Therefore, there is a need to properly characterize disparities in the care and outcomes of minority patients with ADRD. With the diversity of the aging population, one may think that disparities in quality of care are declining; however, current events (including disparities highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic) and data continue to suggest that older minorities are still more likely than their non-Hispanic White counterparts to reside in nursing homes characterized by severe deficiencies in performance, understaffing, and poor care (Fennell et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2021; Mor et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007). These deficiencies and lower performance have resulted in higher mortality rates among nursing homes with higher proportion of minority residents (Kumar et al., 2021). Unfortunately, these disparate patterns of mortality appear to be consistent among residents with ADRD (Rivera-Hernandez, et al., 2018; Rivera-Hernandez et al., 2020), which results in a higher risk of 30-day all-cause mortality among residents with severe cognitive impairment (Panagiotou et al., 2021).

There are about 16 quality indicators that nursing homes report regarding the care of long-stay residents (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020a). These measures are collected from resident assessments and pertain to the quality of care for all nursing home residents, including those with ADRD. However, consistent with CMS’s initiative, the vast majority of the studies have focused on understanding disparities in the inappropriate use of antipsychotics with some literature related to flu vaccination rates (Fashaw et al., 2020; Fossey et al., 2006; Kamble et al., 2008; 2012; Naumova et al., 2009; Ridda et al., 2014). Care for people with ADRD should focus on promoting overall quality of care and well-being (Larson & Stroud, 2021). Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory study was to expand on the literature regarding quality of nursing home care among people with ADRD and assess whether disparities among ADRD Medicare beneficiaries exist beyond antipsychotic medication use and physical restraints. For the purpose of this article, we focused on measures that do not require risk-adjustment and are relatively simple to compute. Thus, facilities that have access to the data can easily replicate these measures. We included both beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are often excluded from studies. However, there are about 40% of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage as of 2021 (Biniek et al., 2020). This enrollment will more likely continue to increase given the current efforts from the federal government to expand coverage and plan availability (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020c). Furthermore, Medicare Advantage is a preferred option among minority older adults, which tend to report higher prevalence of ADRD (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016; Mayeda et al., 2016). In addition, given the critical role of state Medicaid reimbursement policies in determining long-term care and the high enrollment of minority older adults (National Institute on Aging, 2017), we also examined whether these associations differed by dual eligibility.

Methods

Data and Study Population

We linked individual-level data and facility-level characteristics. We used the “Residential History File,” which tracks individuals as they move across healthcare settings through space and time (e.g., nursing homes, hospital, hospice, home, etc.) to identify long-term residents (for more information about the creation of this file see Intrator et al., 2011). Long-stay residents were classified as those with episodes that have total cumulative days in the facility of more than 100 days. These inclusion criteria have been used by prior studies and by CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020a). The Medicare Beneficiary Summary File provided information regarding demographics including Medicare Advantage or fee-for-service enrollment, dual eligibility to Medicare and Medicaid, and resident ZIP Code. The new Research Triangle Institute (RTI) variable on race/ethnicity has high sensitivity and positive predictive value (Eicheldinger & Bonito, 2008). The Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessment provided information including Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia diagnoses and other clinical diagnoses and treatment. Finally, nursing-home level information on ownership, size, staffing, and results from survey was obtained from the Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reports (CASPER) and the Long-term Care: Facts on Care in the US (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2019a; LTC focus, 2017). Our sample included 1,005,781 long-term residents in Medicare Advantage and fee-for-service from 15,137 nursing homes in 2016.

Variables

Long Stay Quality Measures.

We followed the CMS criteria and guidelines (for inclusion and exclusion criteria for each measure see the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2017). Primary quality outcomes of interest included whether: 1) the residents were assessed and appropriately given the seasonal influenza vaccine; 2) the residents received an antipsychotic medication (this measure excludes residents with the following conditions: schizophrenia, Tourette’s syndrome, and Huntington’s disease); 3) the residents experienced one or more falls with major injury; 4) the residents were physically restrained on a daily basis; and 5) the residents lost too much weight (these residents had a weight loss of at least 5% in the last month, or at least 10% in the last 6 months, and were not on a weight-loss regimen).

Resident Characteristics

Demographic characteristics included race and ethnicity, age, sex, fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage insurance, and dual eligibility. Race and ethnic categories were based on the Research Triangle Institute Variable (Eicheldinger & Bonito, 2008) from the beneficiary file which included 1) Non-Hispanic White; 2) Black (or African American); 3) Asian/Pacific Islander; 4) Hispanic; and 5) American Indian/Alaska Native. We also included whether the residents have severe cognitive impairment (i.e., Cognitive Function Scale scores of 4) (Thomas et al., 2015).

Facility Characteristics

We described the following facility characteristics: whether the facility had an Alzheimer’s unit; percentage of residents with Medicaid; whether the facility was part of a chain; whether the facility was for profit; percentage of White residents in the facility; resident acuity index; registered nurse hours per resident per day; certified nurse assistant hours per resident per day; percentage of residents with severe cognitive impairment (i.e., with a Cognitive Function Scale score of 4, which indicates severe cognitive impairment); percentage of residents with schizophrenia/bipolar disorder; percentage of residents with decline in activities of daily living; percentage of residents with daily pain; adjusted rehospitalization rates; adjusted successful discharge rates to the community (home or self-care); adjusted median length of stay (days); percentage of facilities with high star ratings (4/5). All these variables have been used in similar studies (Rivera-Hernandez et al., 2020; Rivera-Hernandez, et al., 2018a; Rivera-Hernandez, et al., 2018b).

Analysis

We described resident, facility, and community characteristics using means and standard deviations. Then we compared associations among these measures between Whites and each minority group by t-tests. We ran regression models for each outcome adjusting for dual eligibility, Medicare type (fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage) age and sex. We included Facility and Zip Code Fixed-effects to account for unobserved facility and community characteristics. Following CMS recommendations, we did not adjust for clinical and/or other patient characteristics (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2017). Full model result estimates (with and without fixed effects) are provided in the Appendix (see Tables A1–A3). We ran additional models including an interaction term between race and dual eligibility to test if there were any differences among minority groups by dual eligibility. For each model, we presented the adjusted means. All models were run using STATA 16.

Results

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of long-term care residents with ADRD. There were 1,005,781 long-term residents in Medicare Advantage and fee-for-service. About 78% were White, 13% Black, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 6% Hispanic, and 0.4% American Indian/Alaska Native. About 67% of all the residents were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. The majority of minority groups were younger (Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native residents), more likely to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native) and had a higher proportion of females (Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native) and residents enrolled in Medicare Advantage (Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic) when compared to White residents. Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic residents were less likely to be classified as having severe cognitive impairment.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Long-Term Residents.

| Non-Hispanic White (n=788,513) | Black (n=130,360) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n=20,350) | Hispanic (n=62,477) | American Indian/Alaska Native (n= 4081) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 84.32 | (9.3) | 80.67 | (10.49) | 85.24 | (8.97) | 82.03 | (9.73) | 80.74 | (9.82) |

| Female, % | 70.33 | 63.00 | 67.22 | 61.06 | 63.46 | |||||

| Severe cognitive impairment, % | 14.58 | 13.49 | 7.83 | 10.15 | 14.58NS | |||||

| Dual, % | 62.26 | 82.00 | 82.3 | 85.15 | 79.17 | |||||

| Medicare Advantage, % | 21.00 | 23.79 | 22.87 | 26.39 | 10.17 | |||||

Notes: Differences between White residents and the other groups significant at p<.05 unless noted with the NS superscript.

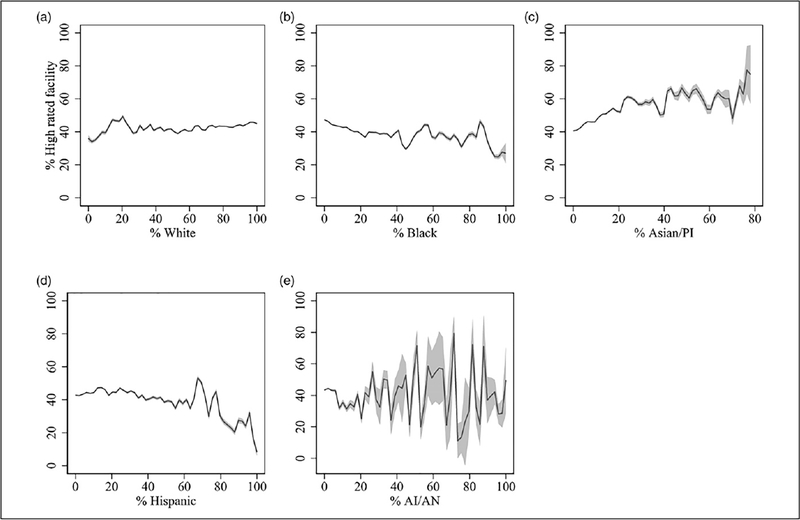

Facility characteristics are shown in Table 2. All minority groups were at least six percentage points less likely to go to nursing homes with an Alzheimer’s unit and facilities which are for profit compared to White residents. Similarly, White residents went to facilities with a high proportion of residents who are from the same racial group (85%). Compared to White, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic residents were slightly more likely to live in nursing homes with a higher proportion of people with severe cognitive impairment (11% vs. 14%, 14%, respectively). Similarly, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and Black residents received care in nursing homes with a lower proportion of residents on antidepressants (38.86, 47.41, and 48.40, respectively). American Indian/Alaska Native residents were more likely to reside in facilities with a higher proportion of residents that reported daily pain (10%) compared to White (7%) residents. Black and Hispanic residents were living in nursing homes with about two percentage points higher readmission rates and they were at least eight percentage points less likely than White residents to go to nursing homes with high-quality ratings. In fact, the proportion of high-quality facilities increased as the proportion of White people increased across Zip codes (see Appendix Figure A1).

Table 2.

Facility Characteristics.

| Non-Hispanic White (n=788,513) | Black (n=130,360) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n=20,350) | Hispanic (n=62,477) | American Indian/Alaska Native (n= 4081) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Facility Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Alzheimer’s unit, % | 24.16 | 16.54 | 11.25 | 14.26 | 18.28 | |||||

| Part of a chain, % | 56.05 | 57.78 | 46.71 | 50.95 | 47.49 | |||||

| For profit, % | 66.83 | 81.23 | 82.25 | 80.90 | 72.87 | |||||

| White in facility, %* | 84.49 | 50.92 | 44.86 | 50.16 | 67.22 | |||||

| Resident acuity index, M (SD) | 12.23 | (1.06) | 12.57 | (1.21) | 12.80 | (1.31) | 12.67 | (1.40) | 11.77 | (1.30) |

| RN HRPPD, M (SD)* | 0.45 | (0.38) | 0.37 | (0.32) | 0.53 | (0.36) | 0.40 | (0.29) | 0.42 | (0.34) |

| CNA HRPPD, M (SD)* | 2.34 | (0.61) | 2.25 | (0.55) | 2.45 | (0.58) | 2.31 | (0.59) | 2.32 | (0.77) |

| Severe cognitive impairment, %* | 11.81 | 12.21 | 13.91 | 13.73 | 10.93 | |||||

| Residents with schizophrenia/bipolar disorder, %* | 9.64 | 14.43 | 10.40 | 13.61 | 10.58 | |||||

| Residents on antidepressants, % | 54.41 | 48.40 | 38.86 | 47.41 | 51.21 | |||||

| Residents with ADL decline, %* | 15.10 | 15.59 | 11.78 | 14.61 | 15.57 | |||||

| Residents with daily pain, %* | 6.70 | 5.27 | 3.89 | 4.52 | 9.60 | |||||

| Adjusted rehospitalization rates, %* | 16.66 | 18.69 | 16.69NS | 18.01 | 16.01 | |||||

| Adjusted successful discharge rates, %* | 63.60 | 62.56 | 63.45 | 64.23 | 64.01 | |||||

| Adjusted median length of stay rates, %* | 22.15 | 23.24 | 24.36 | 22.07 | 23.30 | |||||

| High star rating (4/5), % | 45.02 | 34.84 | 54.03 | 37.62 | 35.48 | |||||

Notes:

Denotes missing values; differences between White residents and the other groups significant at p<.05 unless noted (NS).

Table 3 shows quality outcomes among long-term care residents with ADRD by racial and ethnic groups (Full model results are shown in the Appendix Tables A1, A2, A4). Compared to White residents, most racial/ethnic groups had lower influenza vaccine rates by about one percentage point, except for American Indian/Alaska Native residents. However, White residents reported higher use of antipsychotic medications along with Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native residents (28%, 28%, and 27%, respectively). Yet Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic residents reported slightly higher percentages of physical restraint usage compared to White residents (1.4, 1.4 vs. 1.2, respectively). Similarly, White and American Indians/Alaska Native residents reported having a higher proportion of falls compared to the other groups (9% and 8%, respectively). Finally, Asian/Pacific Islander and American Indians/Alaska Native residents were as likely to report unexpected weight loss compared to White residents (21% for all these groups). All of these differences were significant at p<.05.

Table 3.

Quality Outcomes Among Long-Term Care Residents with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | Flu Vaccine | Antipsychotic Use | One/More Falls | Physically Restrained | Weight Loss |

|

| |||||

| White | 94.07 | 27.89 | 8.55 | 1.20 | 20.66 |

| (94.03–94.11)C | (27.82–27.96)A | (8.50–8.60)B | (1.18–1.22)B | (20.60–20.70)B | |

| Black | 93.68 | 21.21 | 4.61 | 0.73 | 19.72 |

| (93.48–93.88)B | (20.87–21.54) | (4.33–4.90) | (0.65–0.81)A | (19.44–20.00)A | |

| Asian/PI | 93.35 | 22.65 | 7.54 | 1.34 | 20.31 |

| (92.82–93.87) AB | (21.82–23.47) | (6.75–8.34)A | (1.12–1.55) BC | (19.60–21.03) AB | |

| Hispanic | 93.12 | 27.77 | 7.94 | 1.34 | 19.22 |

| (92.83–93.41)A | (27.9–28.25)A | (7.49–8.40)A | (1.22–1.55)C | (18.83–19.61) | |

| AI/AN | 93.82 | 26.67 | 8.32 | 0.76 | 21.26 |

| (92.84–94.79)ABC | (24.78–28.56)A | (6.79–9.95)AB | (0.40–1.13)A | (19.61–22.90) AB | |

| Observations | 993,768 | 949,771 | 462,561 | 1,001,543 | 997,509 |

Notes: Adjusted rates by race/ethnicitywith confidence intervals in parentheses; models are adjusted by sex, age, dual eligibility, Medicare type (fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage) and included both facility and Zip Code Fixed-effects; standard errors were clustered at the facility level; adjusted rates sharing a letter (e.g., superscripts A, B, and/or C) in the group label are not significantly different at the 5% level; all differences are significant at p<.05.

Figure 1 shows the results by race and ethnicity and dual eligibility status. There were small differences among dual and non-dual eligible beneficiaries. Overall, duals with ADRD appeared to have slightly better quality of care than non-dual beneficiaries (p<.001).

Figure 1.

Quality outcomes among long-term care residents with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, by dual eligibility status. Note: Race and ethnic categories 1—White residents; 2—Black residents; 3—Asian/PI residents; 4— Hispanic residents; 5—AI/AN residents.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies exploring racial and ethnic disparities in multiple quality measures among long-term care residents with ADRD. Our study included Asians/Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaska Natives with ADRD, a group that has often been excluded, even though American Indian/Alaska Native residents may have higher incidence of dementia (Mayeda et al., 2016). Our study went beyond looking at inappropriate use of antipsychotic medication by including other measures of quality such as percent of residents who were assessed and given the influenza vaccine, received an antipsychotic medication, experienced one or more falls with major injury, physically restrained on a daily basis, and lost too much weight. Our results suggest that American Indian/Alaska Native residents were more likely to report poor outcomes or performed similarly to White residents in four of the five measures. These indicators included influenza vaccination, antipsychotic medication use, experiencing one or more falls, and unexpected weight loss. However, these differences were relatively small in magnitude (≤1 percentage point).

There were major disparities in access to quality care facilities by minority groups. American Indian/Alaska Native and Black residents were about ten percentage points less likely to go to facilities with high-quality ratings. The proportion of higher quality rated facilities decreased as the proportion of minority residents in the Zip code increased (see Figure A1 in the Appendix). In addition, American Indian/Alaska Native beneficiaries were more likely to reside in facilities with a higher proportion of residents that reported daily pain (≥3 percentage points than other groups). All minority groups were more likely to live in facilities without Alzheimer’s units, facilities that were for profit, and with residents for whom Medicaid was the primary payer. In addition, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic residents (as compared to White residents) were more likely to live in nursing facilities with a higher proportion of people with severe cognitive impairment. However, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and Black residents received care in nursing homes with a lower proportion of residents on antidepressants. These minority groups also experienced racial segregation in the facilities. Consistent with this, all minority groups were from communities with higher levels of segregation, poverty, unemployment, and lower levels of education (see Appendix Table A1).

The present study results extend prior work on racial and ethnic disparities among nursing home residents and people with ADRD (Rivera-Hernandez et al., 2020; Rivera-Hernandez et al., 2018; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Racial and ethnic differences have been documented across the dementia care continuum from detection, diagnosis, and treatment to access to appropriate services (in-home care services or long-term care) and end-of-life care (Chin et al., 2011; Sadarangani et al., 2020; Temkin-Greener et al., 2019; Zuckerman et al., 2008). Others have noted racial/ethnic differences in antidepressant use/prescribing and pain/pain management among nursing home residents (Karkare et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2007; Mack et al., 2018), which may be similar among residents with ADRD. Similarly, prior studies have found that Black and Hispanic residents with ADRD are more likely to receive care in understaffed and poor quality facilities (Rivera-Hernandez et al., 2018). While overall disparities in nursing home care and quality outcomes appear to be declining (Li et al., 2015), there are still substantial differences in access to higher quality facilities—as measured by overall nursing home star ratings—among Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native residents. This may be partially explained by the growing disparities in long-term care choices among minority groups (Smith et al., 2008). Nursing home access is no longer a problem among racial and ethnically diverse groups, including those with ADRD (Rivera-Hernandez et al., 2018). However, White residents have more alternatives for residential care and may be able to afford and prefer to use assisted living facilities (Feng et al., 2011). This may be reflected in the present study by the proportion of White residents with severe cognitive impairment going to higher-quality rated settings. Accordingly, White older adults who tend to have higher income and wealth may be entering nursing homes as a last resort and at a later stage in the disease (Jenkins Morales & Robert, 2020). On the other hand, non-White adults with ADRD continue to experience the effects of systemic racism and structural discrimination in healthcare and long-term services and supports (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Minority adults living in the community are more likely to report unmet needs (e.g., health care and financial planning, assistance with ADLs or home modifications) (Black et al., 2019), which forces them to move to nursing homes earlier (Jenkins Morales & Robert, 2020). In addition, limited availability to high-quality services in communities of color (Bailey et al., 2021) can make it exceedingly difficult for racial and ethnic minorities to receive care in top-rated nursing homes.

There are some limitations in the present study. First, we used data from 2017, which is cross-sectional in nature and limits our ability to explore causal relationships between ethnic disparities in high- or lower-performing facilities. However, our approach was consistent with CMS’s approach (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2017). Second, the five indicators used in this study and by CMS are adequate for all long-term care residents, but not exclusive for residents with ADRD. CMS also reports other quality indicators that were not considered in this study. Future studies may want to consider exploring other quality indicators to assess whether other disparities in ADRD care exists. This also highlights the need to develop alternative measures that may capture and measure the needs of this population better. Third, we are using data from the MDS. These data do not include unmeasured needs or patient/family preferences, which may influence choices in treatment and care (Jenkins Morales & Robert, 2020). Finally, there were only 4081 residents that were American Indian/Alaska Native, which may limit our ability to detect significant differences. However, this is consistent the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). More information about long-term care for people with ADRD and among racial and ethnic groups, especially among American Indian/Alaska Native residents, is needed. This is particularly relevant since the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic—which has disproportionally affected communities of color—has only made these disparities worse (Shippee et al., 2020).

Our work has policy implications. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has not affected everyone in a uniform pattern (Ahmed et al., 2020). This pandemic has highlighted the gap in public health preparedness and healthcare disparities in health outcomes by communities of color in the US, including American Indians/Alaska Natives (Hedgpeth et al., 2020; Hooper et al., 2020) and people with ADRD (Larson & Stroud, 2021). The social gaps of systemic racism and racial and ethnic disparities in access, quality of care, and outcomes are only getting wider due to COVID-19. For instance, non-White residents with ADRD often move to nursing homes due to Medicaid payment regulations (Butler, 2021). Nursing homes were the “ground zero in the COVID-19 epidemic” and residents with ADRD were “COVID-19’s hidden victims” (Arnholz, 2020; Barnett & Grabowski, 2020). At the beginning of the pandemic, higher number of cases and worse outcomes were seen among facilities with lower staffing and quality ratings (Arnholz, 2020; Barnett & Grabowski, 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Nursing homes with higher proportions of racial and ethnic minorities were hit harder at the beginning of the pandemic (Kumar et al., 2021). Right now, experts are calling for policies that will provide better and more equitable care for people in need of long-term services and supports (Butler, 2021). As CMS continues to increase quality among long-term care residents post-COVID-19 pandemic, a major emphasis needs to be placed on eliminating disparities in access to high-quality nursing homes and better long-term care options among minority elders. Future research related to long-term care disparities, structural racism, and discrimination in ADRD care may refer to the National Institute on Aging/National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities framework (Alvidrez et al., 2019) to explore how individual (e.g., insurance coverage), community (e.g., availability of services) and societal level factors (e.g., quality of care) influences quality and outcomes among different groups.

Choosing a nursing home care be a complex and overwhelming process for family members (Gadbois et al., 2017; Shield et al., 2019). In order to streamline the process for people with ADRD, CMS should publish information regarding standards of care for people with ADRD. The National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes is focused on enhancing the use of non-pharmacologic approaches and person-centered dementia care practices (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021a). The website has a number of different resources for family members to be considered when selecting a nursing home (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020b). However, it may be difficult for family members to sort through all this information. In 2015, CMS pilot tested a survey—Focus Dementia Care Survey—to assess prescription of antipsychotic medications and assess compliance with other federal requirements related to ADRD care practices in nursing home settings (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016). However, the majority of this information is not publicly available and/or routinely collected. At the moment, when choosing a residential setting, family members can use 1) CMS nursing home compare to find high-quality facilities and 2) seek out a facility with a dementia special care unit. In addition, family members are encouraged to ask nursing home providers questions related to dementia care such as overall philosophy related to ADRD care, policies, procedures and protocols, staff training, and resources (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021). It should be a priority to provide adequate tools and data for family members to appropriately select care.

In conclusion, Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native residents receive care in lower quality rating facilities. In addition, American Indian/Alaska Native along with White residents reported higher rates of antipsychotic medication use, experiencing one or more falls, inappropriate weight loss, as well as living in facilities with a higher proportion of residents that report daily pain and are on antidepressants. Efforts to understand disparities in access and quality of care—as well as choices of long-term care services and support among American Indian/Alaska Native residents—are needed, especially post-COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported in part by National Institute of Aging grant 5R03AG054686–02; 5K01AG05782201-A1 (Dr Rivera-Hernandez). Dr. Kumar reported receiving research support from the National Institute on Aging (grant: 5R03AG060345–03). Dr. Baldwin received funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant: 5U54MD012388–05).

APPENDIX

Table A1.

Full Model Results Related to Quality Outcomes Among Long-Term Care Residents with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Flu Vaccine | Antipsychotic Use | One/More Falls | Physically Restrained | Weight Loss |

|

| |||||

| Black | −0.00390** | −0.0669*** | −0.0394*** | −0.00472*** | −0.00934*** |

| (0.00121) | (0.00198) | (0.00163) | (0.000472) | (0.00167) | |

| Asian/PI | −0.00726** | −0.0525*** | −0.0101* | 0.00135 | −0.00344 |

| (0.00276) | (0.00435) | (0.00416) | (0.00112) | (0.00374) | |

| Hispanic | −0.00951*** | −0.00123 | −0.00609* | 0.00141* | −0.0143*** |

| (0.00161) | (0.00264) | (0.00245) | (0.000659) | (0.00217) | |

| AI/AN | −0.00252 | −0.0122 | −0.00233 | −0.00439* | 0.00601 |

| (0.00498) | (0.00969) | (0.00837) | (0.00190) | (0.00842) | |

| Age | 0.000781*** | −0.00678*** | 0.000473*** | −0.000125*** | 0.000727*** |

| (3.51 × 10−5) | (6.53 × 10−5) | (5.17 × 10−5) | (1.50 × 10−5) | (5.26 × 10−5) | |

| Female | 0.00692*** | −0.0161*** | 0.0327*** | 0.000617* | 0.00392*** |

| (0.000699) | (0.00121) | (0.000967) | (0.000271) | (0.00104) | |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 0.00339*** | −0.0692*** | −0.00356* | −0.0121*** | −0.0605*** |

| (0.000866) | (0.00152) | (0.00140) | (0.000337) | (0.00125) | |

| Dual eligibility | 0.0406*** | −0.00713*** | −0.00735*** | −0.000702* | −0.0263*** |

| (0.000806) | (0.00119) | (0.00109) | (0.000275) | (0.00109) | |

| Medicare Advantage | −0.0158*** | 0.000781 | −0.00258* | −0.000861** | −0.0321*** |

| (0.000957) | (0.00139) | (0.00120) | (0.000295) | (0.00118) | |

| Constant | 0.846*** | 0.874*** | 0.0299*** | 0.0244*** | 0.176*** |

| (0.00301) | (0.00559) | (0.00443) | (0.00129) | (0.00448) | |

| Observations | 993,768 | 949,771 | 462,561 | 1,001,543 | 997,509 |

| FE and cluster SE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Notes: Models are adjusted by sex, age, dual eligibility, Medicare type (fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage) and included both facility, and Zip-Code Fixed-effects; robust standard errors in parentheses

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05.

Table A2.

Full Model Results Related to Quality Outcomes Among Long-Term Care Residents With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Flu Vaccine | Antipsychotic Use | One/More Falls | Physically Restrained | Weight Loss |

|

| |||||

| Blacks | −0.00901*** | −0.0710*** | −0.0401*** | −0.00451*** | −0.00928*** |

| (0.00149) | (0.00211) | (0.00164) | (0.000518) | (0.00184) | |

| Asian/PI | −0.00451 | −0.0622*** | −0.0110** | 0.00106 | −0.00985* |

| (0.00334) | (0.00464) | (0.00393) | (0.00135) | (0.00415) | |

| Hispanic | −0.00910*** | 0.000118 | −0.00697** | 0.00263*** | −0.0111*** |

| (0.00206) | (0.00302) | (0.00248) | (0.000709) | (0.00247) | |

| AI/AN | −0.00176 | −0.0230* | −0.00198 | −0.00343 | 0.00687 |

| (0.00670) | (0.0117) | (0.00979) | (0.00229) | (0.0101) | |

| Age | 0.00100*** | −0.00683*** | 0.000462*** | −0.000134*** | 0.000674*** |

| (4.33 × 10−5) | (7.34 × 10−5) | (5.38 × 10−5) | (1.65 × 10−5) | (5.78 × 10−5) | |

| Female | 0.00768*** | −0.0154*** | 0.0314*** | 0.000667* | 0.00518*** |

| (0.000823) | (0.00134) | (0.00101) | (0.000297) | (0.00114) | |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 0.00484*** | −0.0718*** | −0.00248 | −0.0116*** | −0.0577*** |

| (0.00103) | (0.00166) | (0.00148) | (0.000336) | (0.00138) | |

| Dual eligibility | 0.0449*** | −0.0107*** | −0.00574*** | 0.000493 | −0.0256*** |

| (0.000963) | (0.00131) | (0.00110) | (0.000305) | (0.00120) | |

| Medicare Advantage | −0.0143*** | −0.000690 | −0.00306** | −0.00206*** | −0.0331*** |

| (0.00104) | (0.00153) | (0.00116) | (0.000340) | (0.00125) | |

| Alzheimer’s unit | −0.00233 | 0.0259*** | 0.00225 | −0.000738 | −0.00184 |

| (0.00174) | (0.00245) | (0.00131) | (0.000792) | (0.00213) | |

| Part of a chain | −0.00703*** | −0.00538** | −0.000318 | −0.00365*** | 0.00396* |

| (0.00151) | (0.00204) | (0.00115) | (0.000651) | (0.00180) | |

| For-profit | −0.0124*** | 0.0112*** | −0.000153 | 0.00202** | −0.000368 |

| (0.00155) | (0.00231) | (0.00127) | (0.000701) | (0.00206) | |

| % White in facility | 0.000375*** | −7.15 × 10−5 | −0.000134*** | −2.48 × 10−7 | −0.000245*** |

| (5.26 × 10−5) | (6.18 × 10−5) | (3.59 × 10−5) | (1.59 × 10−5) | (5.15 × 10−5) | |

| Resident acuity index | 0.000829 | 0.00298** | −0.00156* | 0.00241*** | 0.00551*** |

| (0.000988) | (0.00106) | (0.000622) | (0.000393) | (0.000922) | |

| RN HRPPD | −0.00159 | −0.00253 | −0.00264 | −0.00223* | 0.000672 |

| (0.00251) | (0.00469) | (0.00189) | (0.00105) | (0.00194) | |

| CAN HRPPD | 0.00233 | 9.95 × 10−5 | 0.000211 | 0.00104 | 7.78 × 10−5 |

| (0.00149) | (0.00213) | (0.00115) | (0.000571) | (0.00186) | |

| % Severe cognitive impairment | 0.000363*** | 0.000286* | 3.99 × 10−5 | 0.000259*** | −0.000155 |

| (0.000101) | (0.000134) | (7.29 × 10−5) | (4.28 × 10−5) | (0.000113) | |

| %Residents with schizophrenia/bipolar disorder | −0.000340* | 0.00242*** | 0.000198** | 0.000155** | 8.68 × 10−6 |

| (0.000132) | (0.000157) | (7.49 × 10−5) | (5.59 × 10−5) | (0.000112) | |

| %Residents on antidepressants | 0.000167* | 0.00158*** | 0.000176** | −4.97 × 10−5 | 0.000168* |

| (7.39 × 10−5) | (9.93 × 10−5) | (5.51 × 10−5) | (2.78 × 10−5) | (8.48 × 10−5) | |

| % Residents with ADL decline | −0.000447*** | 0.000495*** | 0.000336*** | −1.77 × 10−6 | 0.000192 |

| (0.000106) | (0.000132) | (7.19 × 10−5) | (3.59 × 10−5) | (0.000117) | |

| %Residents with daily pain | −0.000316** | 0.000707*** | 0.000234** | 0.000176*** | 0.00154*** |

| (0.000116) | (0.000163) | (8.99 × 10−5) | (5.13 × 10−5) | (0.000145) | |

| Adjusted rehospitalization rate | −0.133*** | 0.170*** | 0.0339** | 0.0229** | 0.0986*** |

| (0.0171) | (0.0226) | (0.0127) | (0.00751) | (0.0198) | |

| Adjusted successful discharge | 0.0373*** | −0.0423** | −0.0114 | −0.0118** | 0.0288* |

| (0.0103) | (0.0140) | (0.00735) | (0.00440) | (0.0114) | |

| Adjusted median length of stay | 0.000470*** | 0.000623*** | −9.84 × 10−6 | 0.000169* | 0.000239 |

| (0.000115) | (0.000175) | (8.62 × 10−5) | (7.02 × 10−5) | (0.000132) | |

| %High star rating (4/5) | 0.0107*** | −0.0190*** | −0.00147 | −0.00273*** | −0.00559** |

| (0.00140) | (0.00204) | (0.00113) | (0.000613) | (0.00182) | |

| Less than 9th grade of education | 0.00108*** | 0.000105 | 0.000432* | 0.000254*** | 0.000427 |

| (0.000167) | (0.000270) | (0.000183) | (7.37 × 10−5) | (0.000226) | |

| %Poverty | −4.33 × 10−5 | 8.87 × 10−5 | 0.000117 | 3.18 × 10−6 | 0.000231* |

| (8.54 × 10−5) | (0.000124) | (8.51 × 10−5) | (3.37 × 10−5) | (0.000110) | |

| % Unemployment rate | −0.00119*** | −0.000799** | −0.000320 | 0.000255** | 0.000830*** |

| (0.000218) | (0.000278) | (0.000185) | (8.17 × 10−5) | (0.000250) | |

| %White | −0.000301* | 0.000681*** | 0.000159 | −6.00 × 10−5 | −0.000435** |

| (0.000119) | (0.000182) | (0.000107) | (3.72 × 10−5) | (0.000135) | |

| %Black | −0.000321* | 0.000812*** | 0.000101 | −0.000111** | −0.000444** |

| (0.000130) | (0.000191) | (0.000116) | (4.16 × 10−5) | (0.000145) | |

| %Asian/Pacific Islander | −0.000120 | 0.000574* | −5.98 × 10−6 | −0.000149** | −0.000888*** |

| (0.000150) | (0.000237) | (0.000149) | (4.94 × 10−5) | (0.000177) | |

| %Hispanic | −0.000314*** | 0.000109 | −0.000108 | −0.000164*** | −0.000757*** |

| (6.57 × 10−5) | (0.000100) | (5.94 × 10−5) | (2.30 × 10−5) | (8.02 × 10−5) | |

| % American Indian/Alaska Native | −0.000203 | 0.000782* | 0.000324 | −0.000137 | −0.00116*** |

| (0.000205) | (0.000370) | (0.000230) | (8.09 × 10−5) | (0.000276) | |

| Constant | 0.813*** | 0.644*** | 0.0295 | −0.00298 | 0.116*** |

| (0.0206) | (0.0286) | (0.0158) | (0.00874) | (0.0217) | |

| Observations | 814,639 | 783,448 | 380,304 | 820,934 | 817,337 |

| Cluster SE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Notes: Full models adjusting for individual, facility, and community characteristics; robust standard errors in parentheses

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05.

Table A3.

Adjusted Means Related to Quality Outcomes Among Long-Term Care Residents with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Flu Vaccine | Antipsychotic Use | One/More Falls | Physically Restrained | Weight Loss |

|

| |||||

| White | 0.942*** | 0.272*** | 0.0845*** | 0.0112*** | 0.210*** |

| (0.000731) | (0.00104) | (0.000621) | (0.000312) | (0.000909) | |

| Black | 0.933*** | 0.201*** | 0.0443*** | 0.00673*** | 0.201*** |

| (0.00154) | (0.00196) | (0.00144) | (0.000470) | (0.00177) | |

| Asian/PI | 0.937*** | 0.210*** | 0.0735*** | 0.0123*** | 0.200*** |

| (0.00334) | (0.00457) | (0.00387) | (0.00136) | (0.00411) | |

| Hispanic | 0.933*** | 0.272*** | 0.0775*** | 0.0139*** | 0.199*** |

| (0.00209) | (0.00301) | (0.00235) | (0.000746) | (0.00243) | |

| AI/AN | 0.940*** | 0.249*** | 0.0825*** | 0.00781*** | 0.217*** |

| (0.00670) | (0.0117) | (0.00976) | (0.00229) | (0.0101) | |

| Observations | 814,639 | 783,448 | 380,304 | 820,934 | 817,337 |

Notes: Models are adjusted by all the individual, facility, and community characteristics presented in Table A2; standard errors in parentheses

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05.

Table A4.

Facility and Community Characteristics (Full Table).

| Non-Hispanic White (n=788,513) | Black (n=130,360) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n=20,350) | Hispanic (n=62,477) | American Indian/Alaska Native (n= 4081) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Facility Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Alzheimer’s unit, % | 24.16 | 16.54 | 11.25 | 14.26 | 18.28 | |||||

| Part of a chain, % | 56.05 | 57.78 | 46.71 | 50.95 | 47.49 | |||||

| For profit, % | 66.83 | 81.23 | 82.25 | 80.90 | 72.87 | |||||

| White in facility, %* | 84.49 | 50.92 | 44.86 | 50.16 | 67.22 | |||||

| Resident acuity index, M (SD) | 12.23 | (1.06) | 12.57 | (1.21) | 12.80 | (1.31) | 12.67 | (1.40) | 11.77 | (1.30) |

| RN HRPPD, M (SD)* | 0.45 | (0.38) | 0.37 | (0.32) | 0.53 | (0.36) | 0.40 | (0.29) | 0.42 | (0.34) |

| CNA HRPPD, M (SD)* | 2.34 | (0.61) | 2.25 | (0.55) | 2.45 | (0.58) | 2.31 | (0.59) | 2.32 | (0.77) |

| Severe cognitive impairment, %* | 11.81 | 12.21 | 13.91 | 13.73 | 10.93 | |||||

| Residents with schizophrenia/bipolar disorder, %* | 9.64 | 14.43 | 10.40 | 13.61 | 10.58 | |||||

| Residents on antidepressants, % | 54.41 | 48.40 | 38.86 | 47.41 | 51.21 | |||||

| Residents with ADL decline, %* | 15.10 | 15.59 | 11.78 | 14.61 | 15.57 | |||||

| Residents with daily pain, %* | 6.70 | 5.27 | 3.89 | 4.52 | 9.60 | |||||

| Adjusted rehospitalization rates, %* | 16.66 | 18.69 | 16.69NS | 18.01 | 16.01 | |||||

| Adjusted successful discharge rates, %* | 63.60 | 62.56 | 63.45 | 64.23 | 64.01 | |||||

| Adjusted median length of stay, %* | 22.15 | 23.24 | 24.36 | 22.07 | 23.30 | |||||

| High star rating (4/5), % | 45.02 | 34.84 | 54.03 | 37.62 | 35.48 | |||||

| Community characteristics | ||||||||||

| Less than 9th grade of education, % | 4.55 | 6.27 | 8.30 | 10.79 | 5.81 | |||||

| Poverty, % | 13.95 | 20.76 | 14.52 | 18.99 | 21.34 | |||||

| Unemployment rate, % | 6.89 | 10.07 | 7.25 | 8.46 | 9.79 | |||||

| White, % | 81.08 | 9.02 | 3.66 | 10.83 | 0.64 | |||||

| Black, % | 50.71 | 36.75 | 4.17 | 14.71 | 0.45 | |||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander, % | 52.31 | 8.43 | 24.00 | 23.85 | 0.53 | |||||

| Hispanic, % | 68.34 | 10.71 | 6.21 | 45.30 | 0.68 | |||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native, % | 61.79 | 5.57 | 2.42 | 12.64 | 22.00 | |||||

Notes: Differences between White residents and the other groups significant at p<.05 unless noted with the NS superscript; Community characteristics are at the Zip Code level. These include whether the residents lived in areas with lower levels of education (less than ninth grade), percentage of people living below poverty level, and percentage of unemployment rate. Finally, we described the percentage of people in the community that classified themselves as White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native.

Figure A1.

Proportion of high-rated nursing home facilities by the proportion of people who classified themselves as White (a), Black (b), Asian/PI (c), Hispanic (d), and American Indian/Alaska Native (e).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, & Stiglitz J (2020). Why inequality could spread COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e240. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2016). 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12(4), 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2020). 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures—SPECIAL REPORTon the front lines: Primary care physicians and Alzheimer’s care in America. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf.

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). Residential care. Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. https://alz.org/help-support/caregiving/care-options/residential-care.

- Arnholz J (2020). COVID-19’s hidden victims, Alzheimer’s patients in nursing homes. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/covid-19s-hidden-victims-alzheimers-patients-nursing-homes/story?id=70686559. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, & Bassett MT (2021). How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. The New England Journal of Medicine, 384(8), 768–773. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ML, & Grabowski DC (2020). Nursing homes are ground zero for COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum, 1(3), e200369. DOI: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biniek JF, Freed M, Damico A, & Neuman T (2020). Medicare advantage 2021 spotlight: First look. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2021-spotlight-first-look/. [Google Scholar]

- Black BS, Johnston D, Leoutsakos J, Reuland M, Kelly J, Amjad H, Davis K, Willink A, Sloan D, Lyketsos C, & Samus QM (2019). Unmet needs in community-living persons with dementia are common, often non-medical and related to patient and caregiver characteristics. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(11), 1643–1654. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610218002296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SM (2021). Time to rethink nursing homes. JAMA, 325(14), 1383–1384. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NG, & Ferguson JC (2010). What is nursing home quality and how is it measured? The Gerontologist, 50(4), 426–442. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnq052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2016). Focused dementia care survey tools. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Policy-and-Memos-to-States-and-Regions-Items/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-16-04.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019a). CASPER reporting user’s guide for MDS providers. https://qtso.cms.gov/reference-and-manuals/casper-reporting-users-guide-mds-providers.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019b). U.S. burden of Alzheimer’s disease, related dementias to double by 2060. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0920-alzheimers-burden-double-2060.html.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020a). CMS quality measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/NHQIQualityMeasures.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020b). National partnership – dementia care resources. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/National-Partnership-Dementia-Care-Resources.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020c). Trump administration announces changes to Medicare advantage and Part D to provide better coverage and increase access for Medicare beneficiaries. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-announces-changes-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-provide-better-coverage-and.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021a). National partnership to Improve dementia care in nursing homes. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/National-Partnership-Dementia-Care-Resources#h26sk24spdjxte8ayw7m11x11jpcewa.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021b). Nursing home quality initiative. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2017). MDS 3.0 quality measures: USER’S manual (p. 100). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS-30-QM-Users-Manual-V11-Final.pdf.

- Chatterjee P, Kelly S, Qi M, & Werner RM (2020). Characteristics and quality of US nursing homes reporting cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Network Open, 3(7), e2016930. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin AL, Negash S, & Hamilton R (2011). Diversity and disparity in dementia: The impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 25(3), 187–195. DOI: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Care Central. (2019). Dementia and Alzheimer’s care costs (Updated 2019). https://www.dementiacarecentral.com/assisted-living-home-care-costs/.

- Eicheldinger C, & Bonito A (2008). More accurate racial and ethnic codes for Medicare administrative data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/08springpg27.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fashaw S, Chisholm L, Mor V, Meyers DJ, Liu X, Gammonley D, & Thomas K (2020). Inappropriate antipsychotic use: The impact of nursing home socioeconomic and racial composition. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(3), 630–636. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.16316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Fennell ML, Tyler DA, Clark M, & Mor V (2011). The care span: Growth of racial and ethnic minorities in us nursing homes driven by demographics and possible disparities in options. Health Affairs, 30(7), 1358–1365. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell ML, Feng Z, Clark MA, & Mor V (2010). Elderly hispanics more likely to reside in poor-quality nursing homes. Health Affairs, 29(1), 65–73. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LTC focus. (2017). Long-term care: Facts on care in the US. http://ltcfocus.org/.

- Fossey J, Ballard C, Juszczak E, James I, Alder N, Jacoby R, & Howard R (2006). Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: Cluster randomised trial. BMJ, 332(7544), 756–761. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.38782.575868.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, & Mor V (2017). Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: Individual and family perspectives. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(11), 2459–2465. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.14988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong F, Xu J, & Takeuchi DT (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in perceptions of everyday discrimination. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 3(4), 506–521. DOI: 10.1177/2332649216681587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, Bynum J, Tyler D, & Mor V (2011). End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. The New England Journal of Medicine, 365(13), 1212–1221. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgpeth D, Fears D, & Scruggs G (2020). Indian Country, where residents suffer disproportionately from disease, is bracing for coronavirus. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2020/04/04/native-american-coronavirus/. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper MW, Nápoles AM, & Pérez-Stable EJ (2020). COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA, 323(24), 2466–2467. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, Miller SC, & Mor V (2011). The residential history file: Studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories(*). Health Services Research, 46(1 Pt 1), 120–137. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins Morales M, & Robert SA (2020). Black-white disparities in moves to assisted living and nursing homes among older medicare beneficiaries. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(9), 1972–1982. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/gbz141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MR, Diez-Roux AV, Hajat A, Kershaw KN, O’Neill MS,Guallar E,Post WS,Kaufman JD,&Navas-Acien A (2014). Race/ethnicity, residential segregation, and exposure to ambient air pollution: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). American Journal of Public Health, 104(11), 2130–2137. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016). Profile of Medicare beneficiaries by race and ethnicity: A chartpack. http://kff.org/medicare/report/profile-of-medicare-beneficiaries-by-race-and-ethnicity-a-chartpack/.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2020). Distribution of medicare beneficiaries by race/ethnicity. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/medicare-beneficiaries-by-raceethnicity/. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble P, Chen H, Sherer J, & Aparasu RR (2008). Antipsychotic drug use among elderly nursing home residents in the United States. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 6(4), 187–197. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamble P, Chen H, Sherer JT, & Aparasu DRR (2012). Use of antipsychotics among elderly nursing home residents with dementia in the US. Drugs & Aging, 26(6), 483–492. DOI: 10.2165/00002512-200926060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkare SU, Bhattacharjee S, Kamble P, & Aparasu R (2011). Prevalence and predictors of antidepressant prescribing in nursing home residents in the United States. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 9(2), 109–119. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, & Skinner JS (2015). The burden of health care costs in the last 5 years of life. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(10), 729–736. DOI: 10.7326/M15-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Roy I, Karmarkar AM, Erler KS, Rudolph JL, Baldwin JA, & Rivera-Hernandez M (2021). Shifting US patterns of covid-19 mortality by race and ethnicity from June-December 2020. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(5), 966–970.e3. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson EB, & Stroud C (2021). Meeting the challenge of caring for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers: A report from the national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine. JAMA, 325(18), 1831–1832. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.4928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin CA, Wei W, Akincigil A, Lucas JA, Bilder S, & Crystal S (2007). Prevalence and treatment of diagnosed depression among elderly nursing home residents in Ohio. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 8(9), 585–594. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Harrington C, Temkin-Greener H, Kai Y, Cai X, Cen X, & Mukamel DB (2015). Deficiencies in care at nursing homes and racial & ethnic disparities across homes declined, 2006–11. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(7), 1139. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Temkin-Greener H, Shan G, & Cai X (2020). COVID-19 infections and deaths among connecticut nursing home residents: facility correlates. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(9), 1899–1906. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.16689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JA, & Bowblis JR (2017). CMS strategies to reduce antipsychotic drug use in nursing home patients with dementia show some progress. Health Affairs, 36(7), 1299–1308. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack DS, Hunnicutt JN, Jesdale BM, & Lapane KL (2018). Non-Hispanic Black-White disparities in pain and pain management among newly admitted nursing home residents with cancer. Journal of Pain Research, 11, 753–761. DOI: 10.2147/JPR.S158128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, & Whitmer RA (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12(3), 216–224. DOI: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2020). Alzheimer’s: Dealing with family conflict. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/caregivers/in-depth/alzheimers/art-20047365. [Google Scholar]

- Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, & Grabowski DC (2010). The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 29(1), 57–64. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, & Miller SC (2004). Driven to tiers: Socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Quarterly, 82(2), 227–256. DOI: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging. (2017). Paying for care. National Institute on Aging. http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/paying-care. [Google Scholar]

- Naumova EN, Parisi SM, Castronovo D, Pandita M, Wenger J, & Minihan P (2009). Pneumonia and influenza hospitalizations in elderly people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(12), 2192–2199. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotou OA, Kosar CM, White EM, Bantis LE, Yang X, Santostefano CM, Feifer RA, Blackman C, Rudolph JL, Gravenstein S, & Mor V (2021). Risk factors associated with all-cause 30-day mortality in nursing home residents with COVID-19. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(4), 439–448. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridda I, Dastouri F, King C, Kevin Yin J, Tashani M, & Rashid H (2014). Vaccination of older adults with dementia against respiratory infections. Infectious Disorders - Drug TargetsDisorders), 14(2), 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Hernandez M, Fabius CD, Fashaw S, Downer B, Kumar A, Panagiotou OA, & Epstein-Lubow G (2020). Quality of post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities that disproportionately serve hispanics with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(11), 1705–1711.e3. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Hernandez M, Kumar A, Epstein-Lubow G, & Thomas KS (2018a). Disparities in nursing home use and quality among African American, hispanic, and white medicare residents with alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Journal of Aging and Health, 31(7), 1259–1277. DOI: 10.1177/0898264318767778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Hernandez M, Rahman M, Mukamel DB, Mor V, & Trivedi AN (2018b). Quality of post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities that disproportionately serve black and hispanic patients. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 74(5), 689–697. DOI: 10.1093/gerona/gly089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadarangani TR, Salcedo V, Chodosh J, Kwon S, Trinh-Shevrin C, & Yi S (2020). Redefining the care continuum to create a pipeline to dementia care for minority populations. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 11, 1–4. DOI: 10.1177/2150132720921680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shield R,Winblad U, McHugh J, Gadbois E, & Tyler D (2019). Choosing the best and scrambling for the rest: Hospital-nursing home relationships and admissions to post-acute care. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 38(4), 479–498. DOI: 10.1177/0733464817752084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee TP, Akosionu O, Ng W, Woodhouse M, Duan Y, Thao MS, & Bowblis JR (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: exacerbating racial/ethnic disparities in long-term services and supports. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 323–333. DOI: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1772004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn JS, & Mor V (2007). Separate and unequal: racial segregation and disparities in quality across u.s. nursing homes. Health Affairs, 26(5), 1448–1458. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn J, & Mor V (2008). Racial disparities in access to long-term care: The illusive pursuit of equity. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 33(5), 861–881. DOI: 10.1215/03616878-2008-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin-Greener H, Yan D, Wang S, & Cai S (2019). Racial disparity in end-of-life hospitalizations among nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(7), 1877–1886. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.17117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JPW, Leland NE, Miller SC, Morden NE, Scupp T, Goodman DC, & Mor V (2013). Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA, 309(5), 470–477. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, & Mor V (2015). The minimum data set 3.0 cognitive function scale. Medical Care, 55(9), e68–e72. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). Racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease: A literature review (p. 34). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-alzheimers-disease-literature-review. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services; Office of the Inspector General. (2015). National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2015 update. ASPE. https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plan-address-alzheimer%E2%80%99s-disease-2015-update. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman IH, Ryder PT, Simoni-Wastila L, Shaffer T, Sato M, Zhao L, & Stuart B (2008). Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia among medicare beneficiaries. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(5), S328–S333. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.S328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]