Short abstract

Content available: Author Interview and Audio Recording

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

- CSPH

clinically significant portal hypertension

- EVL

endoscopic variceal ligation

- GEV

gastroesophageal varices

- HR

heart rate

- HTN

hypertension

- HVPG

hepatic venous pressure gradient

- NA

not applicable

- NSBB

nonselective beta‐blocker

- PH

portal hypertension

- PREDESCI

Study on β‐blockers to Prevent Decompensation of Cirrhosis With Portal Hypertension

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Watch the interview with the author.

Listen to an audio presentation of this article.

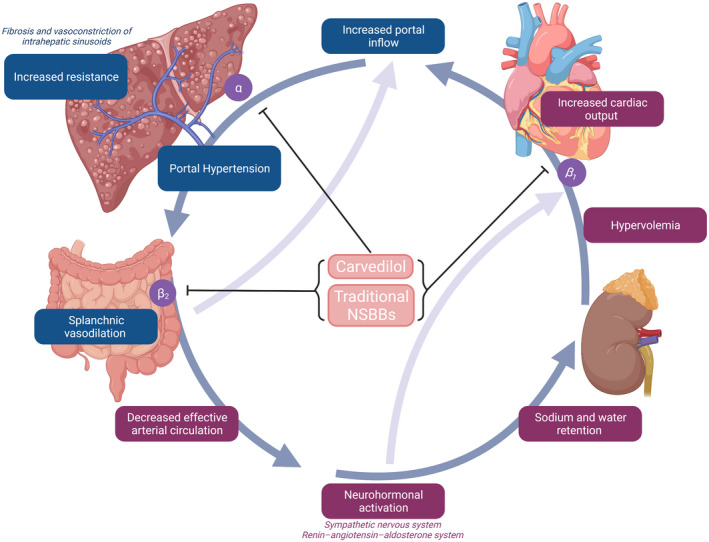

In the past three decades, nonselective beta‐blockers (NSBBs) have been the cornerstone in the management of portal hypertension (PH) in patients with cirrhosis. PH in cirrhosis initially develops as a result of increased hepatic resistance (architectural distortion and intrahepatic vasoconstriction). This initial increase in pressure leads to splanchnic vasodilation resulting in an increased portal venous inflow and a further increase in portal pressure. In addition, vasodilation leads to decreased effective arterial blood volume and to compensatory neurohormonal activation resulting in sodium and water retention from the kidneys, plasma volume expansion, and an increase in cardiac output (hyperdynamic circulation). This further augments portal venous inflow and pressure, thereby creating a vicious cycle 1 (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Pathophysiology of PH. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

NSBBs were first shown to reduce portal pressure in patients with variceal hemorrhage in 1980. 2 In contrast with cardioselective beta‐blockers whose affinity is specific for β1 (located in cardiac muscles), NSBBs such as propranolol or nadolol have a similar affinity for β1 and β2 (located in splanchnic vessels). Blocking β1 results in decreased cardiac output, and blocking β2 results in splanchnic vasoconstriction, both of which contribute to decreasing portal pressure. Carvedilol, a newer NSBB, additionally blocks α1‐adrenergic receptors, which decreases intrahepatic resistance, with a consequent greater reduction in portal pressure. 1

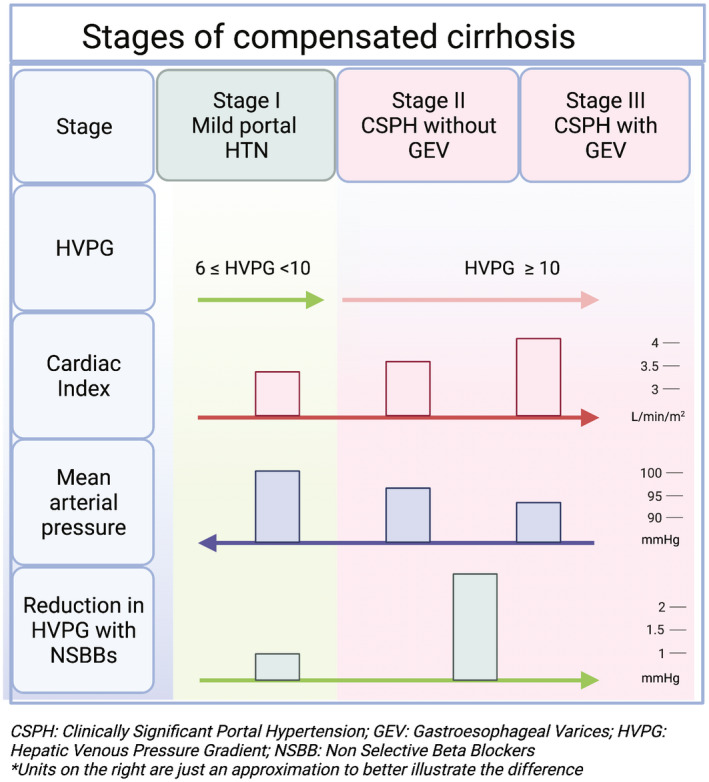

The effect of NSBBs depends on the stage of cirrhosis and PH. In compensated cirrhosis, PH is initially mild with a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) of 6 to 10 mm Hg. With the onset of the hyperdynamic circulation, HVPG increases to >10 mm Hg, a threshold identified as being “clinically significant PH (CSPH)” because it is the main predictor of cirrhosis decompensation. 3 NSBBs play a major role in the treatment of PH in patients in whom hyperdynamic circulation has developed, that is, those with CSPH and those who have bled from varices 4 (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Stages of compensated cirrhosis and hemodynamic characteristics. *Units on the right are just an approximation to better illustrate the difference. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

We will discuss the major indications of NSBBs and future directions.

Primary Prophylaxis of Variceal Hemorrhage

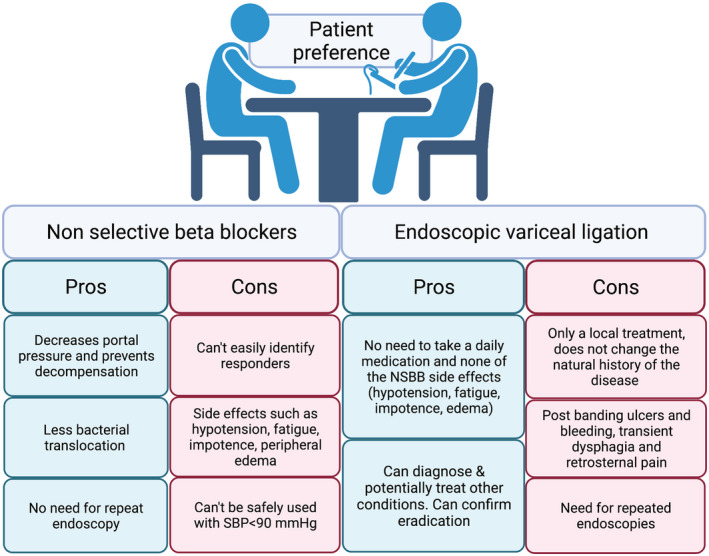

Currently, guidelines recommend NSBBs or endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) to prevent first variceal hemorrhage (primary prophylaxis) in patients with high‐risk varices. High‐risk varices are defined as medium‐to‐large varices, varices of any size with red wale marks, or varices of any size in patients with Child class C. 5 Treatment selection is based on patient and provider preference, but guided by data on benefits and risks.

When used for primary prophylaxis, NSBBs have also been shown to decrease decompensation, as opposed to EVL, which is a local treatment and does not alter the disease progression. NSBBs can additionally decrease intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation. 6 , 7 , 8 Also, once a patient is on NSBBs, the risk for bleeding is reduced similarly to eradication of the varices with EVL, and thus repeat endoscopy is not required. 9 The risks or drawbacks of each approach, however, are real. Thus, it is important to individualize treatment selection based on contraindications, tolerance, side effect profile, and patient preference (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Pros and cons of NSBBs versus EVL for primary prophylaxis. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

Secondary Prophylaxis of Variceal Hemorrhage

In patients who have previously bled from varices, combination therapy with NSBBs and EVL is recommended. 5 Multiple trials have demonstrated the benefits of combination therapy over either of these treatments alone. Interestingly, NSBBs have been shown to be the key component of the combination therapy and drive the majority of the benefit. 1

Despite their proven efficacy, there is hesitancy in using NSBBs in patients with decompensated cirrhosis with ascites, because retrospective studies have shown increased mortality in these patients. 10 Despite initial concerns, recent meta‐analyses showed an overall survival benefit with appropriate dosing of NSSBs in subgroup analyses of patients with ascites or even refractory ascites. 11 NSBBs should be used with caution in patients with refractory ascites because it is in these patients that NSBBs can lead to a decrease in renal perfusion pressure and acute kidney injury. 12 It is important that mean arterial pressure is maintained at greater than 65 mm Hg in patients with ascites because this will not only prevent kidney injury, but it is the threshold pressure that has been associated with improved survival. 13 In addition, it should be noted that the maximal recommended doses of NSBBs are lower compared with patients without ascites (Table 1). 5

TABLE 1.

NSBBs Used in PH

| NSBB | Frequency | Starting Dose (mg) | Therapy Goal | Maximum Dose (mg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Ascites | With Ascites | With or Without Ascites | No Ascites | With Ascites | |||

| Propranolol | Twice a day | 20‐40 | 10‐20 | HR: 55‐60 | Maintain SBP > 90 | 320 | 160 |

| Nadolol | Daily | 10‐20 | 10‐20 | 160 | 80 | ||

| Carvedilol | Daily | 6.25‐12.5 | NA | No HR goal | 12.5‐25* | NA | |

Maximum dose used in PREDESCI was 25 mg.

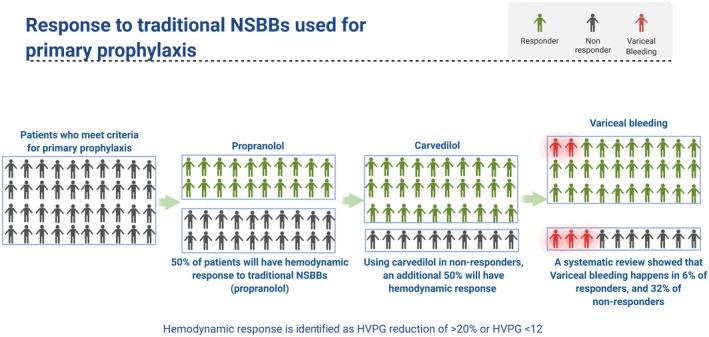

Preventing Clinical Decompensation

NSBBs have been used for many years for variceal bleeding prophylaxis. Previous studies have shown that the benefits of NSBBs are mainly observed in hemodynamic responders (defined as patients with HVPG reduction of >20% or HVPG < 12 mm Hg), but only 50% of patients respond to traditional NSBBs (Fig. 4). 14 Traditional NSBB dose is often titrated to a goal heart rate (HR). However, this dogma has been challenged. First, patients at goal HR are just as likely to have reduced HVPG as they are not to on follow‐up HVPG measurements. 15 Second, each given point estimate of HVPG has wide confidence intervals owing to measurement error and patient factors, particularly among those with decompensated cirrhosis, which can result in significant day‐to‐day changes in HVPG. Accordingly, HVPG measurement is insensitive to detect changes in pressures that are <30%. 16 Third, using carvedilol in patients who do not respond to traditional NSBBs increases the proportion of responders to 75%. 17 Given these difficulties in identification of responders, an alternative approach could be to use carvedilol as the first‐line treatment.

FIG 4.

Response to NSBBs and prevention of variceal bleed. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

As the pathophysiology of portal HTN is better clarified, there has been an increased interest in extending the indications for NSBBs to earlier stages. In this backdrop, the PREDESCI (Study on β‐blockers to Prevent Decompensation of Cirrhosis With Portal Hypertension) trial evaluated the role of NSBBs in patients with CSPH with no or small varices. 18 Patients were randomized to propranolol (or carvedilol in cases where HVPG did not decline by 10% on propranolol) or placebo. The primary outcome was a composite of decompensation (ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or encephalopathy) or death. Notably, although the decision to use carvedilol was made for those lacking hemodynamic response to propranolol, HVPG response was not assessed after starting it. The cumulative incidence of decompensation or death was significantly lower in the NSBB group compared with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.26–0.97). The number needed to treat to prevent one decompensation was 9 (3‐year follow‐up). This difference was largely due to a lower appearance of ascites in this group compared with placebo (9% versus 20%).

Features of this study, however, limit generalizability. First, HVPG assessment is not part of usual care. It is unclear whether identification of CSPH via noninvasive methods (i.e., using liver stiffness values) would provide similar results. Second, there is uncertainty about the utility of measurement of hemodynamic response to NSBBs in clinical practice outside of expert centers.

This landmark study could shift the paradigm of how we treat CSPH and compensated cirrhosis with the goal of changing the natural history of the disease rather than just preventing variceal bleeding. More studies are needed to show feasibility, benefit, and lastly uptake in real‐world clinical practice, where comorbidities such as diastolic dysfunction and kidney disease may influence effects.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health through National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant 1K23DK117055‐01A1 to E.B.T.).

Potential conflict of interest: E.B.T. consults for Novartis and Allergan, advises Mallinckrodt and Bausch Health, and has received grants from Gilead and Valeant.

References

- 1. Garcia‐Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:823‐832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lebrec D, Corbic M, Nouel O, et al. Propranolol—a medical treatment for portal hypertension? Lancet 1980;316:180‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turco L, Garcia‐Tsao G, Magnani I, et al. Cardiopulmonary hemodynamics and C‐reactive protein as prognostic indicators in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018;68:949‐958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villanueva C, Albillos A, Genescà J, et al. Development of hyperdynamic circulation and response to β‐blockers in compensated cirrhosis with portal hypertension: Liver Failure/Cirrhosis/Portal Hypertension. Hepatology 2016;63:197‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garcia‐Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2017;65:310‐335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hernández‐Gea V, Aracil C, Colomo A, et al. Development of ascites in compensated cirrhosis with severe portal hypertension treated with β‐blockers. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:418‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Villanueva C, Aracil C, Colomo A, et al. Acute hemodynamic response to β‐blockers and prediction of long‐term outcome in primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2009;137:119‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reiberger T, Ferlitsch A, Payer BA, et al. Non‐selective betablocker therapy decreases intestinal permeability and serum levels of LBP and IL‐6 in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2013;58:911‐921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gluud LL, Krag A. Banding ligation versus beta‐blockers for primary prevention in oesophageal varices in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD004544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sersté T, Melot C, Francoz C, et al. Deleterious effects of beta‐blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology 2010;52:1017‐1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chirapongsathorn S, Valentin N, Alahdab F, et al. Nonselective β‐blockers and survival in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1096‐1104.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Téllez L, Ibáñez‐Samaniego L, Pérez del Villar C, et al. Non‐selective beta‐blockers impair global circulatory homeostasis and renal function in cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites. J Hepatol 2020;73:1404‐1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tergast TL, Kimmann M, Laser H, et al. Systemic arterial blood pressure determines the therapeutic window of non‐selective beta blockers in decompensated cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:696‐706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albillos A, Bañares R, González M, et al. Value of the hepatic venous pressure gradient to monitor drug therapy for portal hypertension: a meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1116‐1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abraldes J. Hemodynamic response to pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension and long‐term prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology 2003;37:902‐908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bai W, Al‐Karaghouli M, Stach J, et al. Test–retest reliability and consistency of HVPG and impact on trial design: a study in 289 patients from 20 randomized controlled trials. Hepatology 2021. 10.1002/hep.32033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reiberger T, Ulbrich G, Ferlitsch A, et al. Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non‐response to propranolol. Gut 2013;62:1634‐1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Villanueva C, Albillos A, Genescà J, et al. β blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (PREDESCI): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2019;393:1597‐1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]