Abstract

Gallbladder volvulus is a rare entity. It has been attributed to an elongated gallbladder mesentery, predisposing the gallbladder to twisting, obstructing the cystic duct and vessels, thus leading to ischemia and gangrene. Preoperative diagnosis can be elusive, but radiological features across multiple modalities have been described in the literature. We report a case of gallbladder volvulus in which the gallbladder appeared to be left-sided based on imaging, and present the radiological findings in keeping with a volvulus. Unlike cholecystitis, the treatment for volvulus is prompt detorsion and cholecystectomy; thus, accurate and timely diagnosis is paramount.

Keywords: Gallbladder volvulus, Gallbladder torsion, Left-sided gallbladder, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Case report

Introduction

Gallbladder volvulus is considered a rare entity, with a reported hospitalization rate of 1 in 365,520 [1]. It occurs when the gallbladder twists on its pedicle, thus occluding the cystic duct, artery and vein. Preoperative diagnosis can be elusive; however, it is important to recognize so that surgery is not delayed. We report a case of gallbladder volvulus in which the gallbladder appeared to be left-sided on radiological scans. Common imaging modalities and surgical management will be discussed.

Case report

An 81-year-old Caucasian female presented to the Emergency Department with 4 days of abdominal pain, described as ‘gripping’ in nature, initially generalized but gradually localized to the periumbilical and left side of the abdomen, associated with nausea and vomiting. She was otherwise well without any significant comorbidities, and had undergone right total hip arthroplasty a few years ago. Her height was 162 cm, and she weighed 58 kg. On physical examination, her pulse rate was 95 beats per minute, blood pressure was 155/89 mmHg and temperature were 36.7°C. Her abdomen was not distended, but she was focally tender in the left upper quadrant, with a tense, palpable mass. There was no scleral icterus or jaundice. She had an elevated white cell count of 12 × 109/L, C-reactive protein of 290 mg/L, and total bilirubin of 30 µmol/L, but otherwise her blood test results were regular.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a grossly distended gallbladder lying in an unusual position to the left of midline, with cholecystitis features evidenced by pericholecystic fat stranding. Radio-opaque gallstones were seen. On the sagittal view, there appeared to be a ‘swirl’ involving the gallbladder neck and cystic duct (Fig. 1A), which raised the suspicion of a torted gallbladder. Her ultrasonography scan again demonstrated again demonstrated the abnormal lie of the gallbladder located at the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, with mobile cholelithiasis. There was mural thickening up to 12 mm, without hyperemia, and only mild tenderness on probe pressure (Fig. 2). A diagnosis of cholecystitis was made, but a gallbladder volvulus was deemed unable to be confirmed or excluded based on the ultrasound.

Fig. 1.

CT images. (A) There is a ‘swirl’ involving the gallbladder neck and cystic duct (*). (B) The distended gallbladder (orange star) is displaced to the left side. (C) The distended lumen of the gallbladder transitions to the narrow fulcrum points at its neck, giving rise to a “beak” sign (red <).

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound images. (A) The region of interest (ROI) is in the left upper abdominal quadrant (LUQ), where the gallbladder is located. It features a thickened wall with hypoechoic lines (arrowheads), dependent stones and sludge (*) with posterior acoustic shadowing. (B) A conical-shaped pedicle (<) emerges from the inferior border of the left lobe of the liver (L). (C) The gallbladder is mainly under the abdominal wall rather than in its usual fossa beneath the liver, with mild pericholecystic fluid. (D) There is absence of wall hyperemia.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was organized for the patient on the following day of her admission. Given the abnormal lie of the gallbladder, she was presumed to have a left-sided gallbladder. The operative technique was modified from the usual American-style setup where the surgeon operates from the patient's left, to the French technique where the patient is in the lithotomy position and the surgeon stands between the legs; this is to improve instrument triangulation and physical ergonomics.

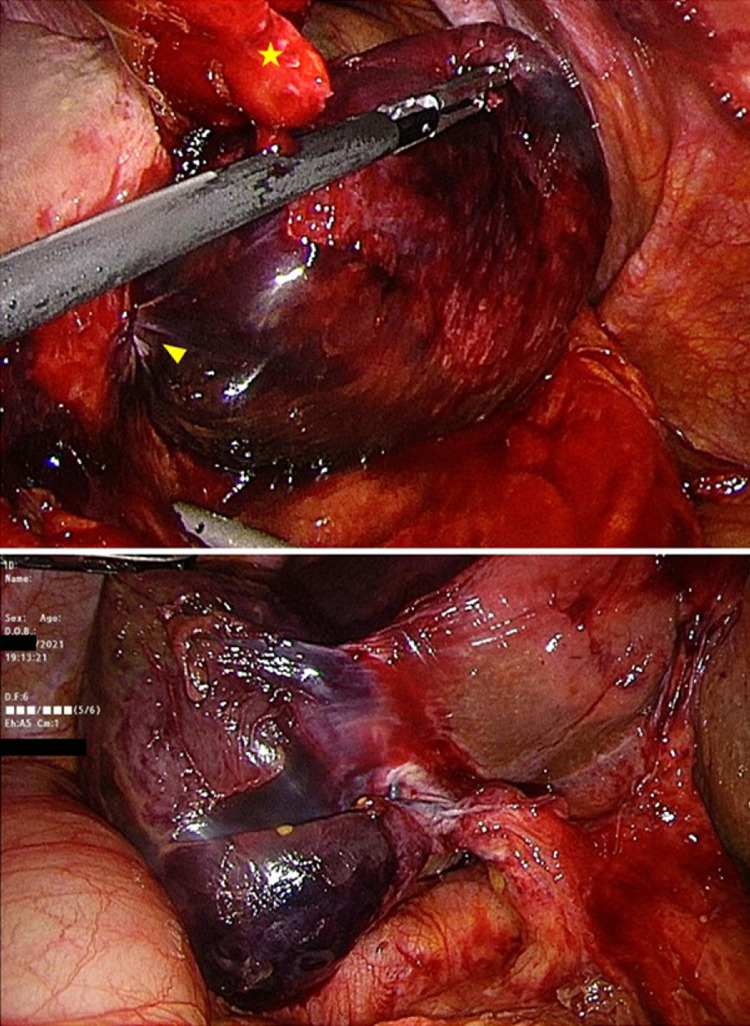

Intraoperatively, the gallbladder was distended and gangrenous with dense surrounding adhesions. It was decompressed (Fig. 3). After dividing and elevating the falciform ligament, it became apparent that the gallbladder had torted around its pedicle in a 270° clockwise direction. A mesentery that was attached to the liver bed supported the gallbladder body and cystic duct (Fig. 4). Detorsion was performed, and the gallbladder was returned to the right side of the ligamentum teres. The rest of the operation proceeded in a routine fashion, with a normal intraoperative cholangiogram. Histopathologically, there was widespread transmural ischemic-type necrosis, with vascular congestion and hemorrhage in the submucosa. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on day 2 postoperation.

Fig. 3.

Laparoscopic decompression of the gallbladder.

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative photographs. (A) The large gangrenous gallbladder lies to the left of the ligamentum teres (yellow star), with a fulcrum point at its neck (yellow arrowhead). (B) Post detorsion, the gallbladder is seen attached to the liver by its mesentery.

Discussion

Since Wendel's initial description of a ‘floating gallbladder’ in 1898 [2], gallbladder volvulus has been documented in numerous reports and case series. By definition, it implies a rotation of the gallbladder on its axis along the cystic duct [3], although a rotation involving solely the gallbladder fundus with the body as its fulcrum has been reported [4]. It can be clockwise or anticlockwise, complete (with a rotation of at least 180 degrees, with up to 1080 degrees described [5]) or incomplete (rotation less than 180 degrees) and are not thought to be associated with gallstones [6]. Cholelithiasis has been found in only 24%-32% of cases [6,7].

It has been well-established that amongst the adult population, elderly women with an asthenic habitus were most likely to be afflicted with gallbladder volvulus [5]. Its incidence peaks in late life between 60 and 80 years old, and hence is expected to grow in accordance with the extending life expectancy of the population [8]. In adults, there is a preponderance for females to have gallbladder torsion, with a ratio of 3:1-5:13,9, versus the pediatric population, where males are more likely to be affected [7].

Multiple theories have been posited to explain its etiology. In 4% of the population, the gallbladder possesses a long fold or mesentery, allowing it to hang from the inferior surface of the liver [1]. This mesentery may encase the entire gallbladder length and cystic duct, or involve the cystic duct alone [5]. It has been postulated that the delay of torsion until later in life may be due to age-related atrophy of surrounding tissues and dissipation of supporting fat, causing the visceral organs to become more ptotic [5]. Being freely mobile, the gallbladder may become twisted on its pedicle; the cystic artery and vein are occluded, resulting in an infarcted gallbladder.

Patients with gallbladder volvulus tend to experience sharp, severe abdominal pain of abrupt onset, nausea with or without vomiting, and a short course of illness, likely related to the intensity of symptoms precipitating early presentation [8]. On examination, patients are usually tachycardic but afebrile (described as a ‘pulse-temperature discrepancy’), and may have a tender, palpable abdominal mass. Very few patients are toxic or jaundiced [3]. These clinical features have been summarized as a ‘triad of triads’ [8]. However, abdominal pain and emesis are non-specific symptoms, and physical signs may be inconsistent (for example, fever can be a feature in up to 28% of patients [3,9]).

Common imaging modalities such as ultrasound and CT remain the primary diagnostic strategies. Plain abdominal x-rays are not generally helpful [3]; nevertheless, there have been reports of gallbladder volvulus appearing as a soft tissue mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen with downward displacement or compression of the colon [8,10]. Ultrasonography allows for detecting a gallbladder located outside its anatomical fossa, usually massively distended with a thickened wall and pericholecystic fluid [6,7]. More specific pathognomonic features have been proposed, such as finding a continuous hypoechoic line in the wall, thought to be secondary to oedema from a combination of venous and lymphatic obstruction [6,11]. The twisted pedicle of a torted gallbladder can manifest as a stretched conical-shaped structure found at the gallbladder neck with several linear echoes converging towards its tip [1]. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess for lack of blood flow indicating obstruction of the cystic artery [3].

Gallbladder volvulus has been evaluated on abdominal CT scans. Kitagawa et al. [10] proposed 4 diagnostic criteria: (1) presence of fluid between the gallbladder and the gallbladder fossa, (2) horizontal lie of the gallbladder, (3) presence of an enhancing cystic duct situated on the gallbladder's right, and (4) evidence of gallbladder inflammation or ischemia such as oedema or wall thickening. Layton et al. [12] counters that most of these findings are non-pathognomonic and may also be found in advanced acute cholecystitis; instead, they offer a combination of 3 criteria: (1) a distended gallbladder, (2) a twist in the vascular pedicle which typically shifts the gallbladder axis from vertical to horizontal, and (3) the presence of a curved “beak” as the distended lumen transitions to the narrow fulcrum point, coupled with a “swirl” sign due to the twisting of the vascular pedicle and surrounding fat. These findings were present in our patient's CT (Fig. 1). Moser et al. [3] prefer magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in diagnosing gallbladder volvulus; in addition to gallbladder distension, pericholecystic fluid and gallbladder dislocation outside its anatomical fossa, there may be loss of gallbladder enhancement relative to the extrahepatic ducts and sudden tapering of the cystic duct. There may also be a ‘V’-shaped distortion of the extrahepatic bile duct, as though being pulled by the cystic duct [13,14]. Cholescintigraphy has also been used; it may not reveal the gallbladder because the tracer cannot enter its lumen due to cystic duct obstruction [10,15]. The tracer can still enter a patent common bile duct, causing focal accumulation of the radioactive substance medial to a photopenic gallbladder, thus manifesting as a “bulls-eye” pattern [15].

Urgent surgery should be performed before gallbladder gangrene and perforation occur. Open cholecystectomy was previously favored, although laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now preferred for patients who can tolerate pneumoperitoneum [3,16]. Robotic cholecystectomy has been reported [17]. One case described a patient who had percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration followed by open cholecystectomy where gallbladder volvulus was diagnosed preoperatively [13]. In our patient's case, a surgical decision was made to modify the port placement and positions of the surgeon and assistant on the presumption that the gallbladder was left-sided. It was thought more prudent to err on the side of caution as cholecystectomy of a left-sided gallbladder conveyed a higher risk of bile duct injury, open conversion, and thus patient morbidity [18]. Fortunately, after detorsion, the gallbladder is usually removed relatively easily [5].

Historically, less than 10% of patients were diagnosed with a gallbladder volvulus preoperatively [6]; this has improved to 17%-26% in more recent reviews, likely attributable to improvements in imaging techniques [7,14]. Preoperative diagnosis can still be challenging [3]; differential diagnoses include a left-sided gallbladder due to the similar radiological features such as dislocation and twisting of the cystic duct [18]. The mortality rate is about 6%, although in a review by Reilly et al. [7], no deaths occurred in patients who were diagnosed preoperatively. Prompt recognition of gallbladder volvulus is imperative since the mortality rate rises when surgery is delayed, unlike the common acute cholecystitis where a patient can be safely managed nonoperatively with broad-spectrum antibiotics [3]. With timely operative management, the prognosis is usually excellent [7].

Conclusion

In an ageing population, gallbladder volvulus may occur more frequently; hence it is essential to recognize its critical clinical and radiological signs. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical management usually result in optimal patient outcomes.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. The personal details of the patient have been removed. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the journal on request.

Ethical approval

The case report is exempt from ethical approval at the affiliated institutions, as per the policy directive ‘Research - Ethical & Scientific Review of Human Research in NSW Public Health Organizations’ [Document Number PD2010_055].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Li Xian Lim: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Humaira Haider Mahin: Writing – review & editing. David Burnett: Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Yeh H., Weiss M., Gerson C. Torsion of the gallbladder: the ultrasonographic features. J Clin Ultrasound. 1989;17(2):123–125. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870170211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendel A.V.V.I. A case of floating gall-bladder and kidney complicated by cholelithiasis, with perforation of the gall-bladder. Ann Surg. 1898;27(2):199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moser L., Joliat G.R., Tabrizian P., Di Mare L., Petermann D., Halkic N., et al. Gallbladder volvulus. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10(2):249. doi: 10.21037/hbsn-20-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aharoni D., Hadas-Halpern I., Fisher D., Hiller N. Torsion of the fundus of gallbladder demonstrated on ultrasound and treated with ERCP. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25(3):269–271. doi: 10.1007/s002610000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross R.E. Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder: a review of one. hundred and forty-eight cases, with report of a double gallbladder. Arch Surg. 1936;32(1):131–162. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1936.01180190134008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakao A., Matsuda T., Funabiki S., Mori T., Koguchi K., Iwado T., et al. Gallbladder torsion: case report and review of 245 cases reported in the Japanese literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6(4):418–421. doi: 10.1007/s005340050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly D.J., Kalogeropoulos G., Thiruchelvam D. Torsion of the gallbladder: a systematic review. HPB. 2012;14(10):669–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau W.Y., Fan S.T., Wong S.H. Acute torsion of the gall bladder in the aged: a re-emphasis on clinical diagnosis. ANZ J Surg. 1982;52(5):492–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1982.tb06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn S.F., Fazzio F., Jones E. Torsion of the gallbladder: findings on CT and sonogram and role of percutaneous cholecystostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148(5):881–882. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitagawa H., Nakada K., Enami T., Yamaguchi T., Kawaguchi F., Nakada M., et al. Two cases of torsion of the gallbladder diagnosed preoperatively. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32(11):1567–1569. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron E.W., Beale T.J., Pearson R.H. Case report: torsion of the gall-bladder on ultrasound–differentiation from acalculous cholecystitis. Clin Radiol. 1993;47(4):285–286. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Layton B., Rudralingam V., Lamb R. Gallbladder volvulus: it's a small whirl. BJR Case Rep. 2016;2(3) doi: 10.1259/bjrcr.20150360. 20150360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuhashi N., Satake S., Yawata K., Asakawa E., Mizoguchi T., Kanematsu M., et al. Volvulus of the gall bladder diagnosed by ultrasonography, computed tomography, coronal magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(28):4599–4601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Usui M., Matsuda S., Suzuki H., Ogura Y. Preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder torsion by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(2):218–222. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang G.J., Colln M., Crossett J., Holmes R.A. “Bulls-eye” image of gallbladder volvulus. Clin Nucl Med. 1987;12(3):231–232. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198703000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezaki S., Tomimaru Y., Noguchi K., Noura S., Imamura H., Dono K. Surgical results of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder torsion. Am Surg. 2019;85(5):471–473. doi: 10.1177/000313481908500522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bustos R., Mashbari H., Gangemi A. First report of gallbladder volvulus managed with a robotic approach. Case Rep Surg 2019 Jul 14;2019:2189890. doi: 10.1155/2019/2189890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Hirohata R., Abe T., Amano H., Kobayashi T., Nakahara M., Ohdan H., et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in a patient with left-sided gallbladder: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2019;5(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s40792-019-0614-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]