Abstract

Previous research posits that individual predispositions play an essential role in explaining patterns of selective exposure to political information. Yet the contextual factors in the political information environment have received far less attention. Using a cross-national and quasi-experimental design, this article is one of the first to investigate how political information environments shape selective exposure. We rely on a unique two-wave online survey quasi-experiment in five countries (Switzerland, Denmark, Italy, Poland and the United States) with 4349 participants to test the propositions that (a) the level of polarization and fragmentation in information environments and (b) the type of media source used affect selective exposure. Our results reveal that selective exposure is slightly more frequent among regular social media users but is less common among users of TV, radio and newspapers; crucially, it is more common in information environments that are highly fragmented and polarized. Nevertheless, news users from less fragmented-polarized media landscapes show one surprising yet intriguing behaviour: in a quasi-experimentally manipulated setting with more opportunities to self-select than they may be accustomed to, their coping strategy is to pick larger amounts of congruent news stories. All our findings imply that contextual factors play a crucial role in moderating individuals’ tendency to select information that aligns with their political views.

Keywords: International comparison, media fragmentation, media polarization, news, political information environment, selective exposure

Introduction

Media fragmentation and polarization create a situation where news users are confronted with an abundant choice of media outlets that have different ideological leanings. In such contexts, audiences may seek out media outlets that best fit their interests and preferences (Mutz and Martin, 2001), thereby creating their own information cosmos tailored to their political predispositions and walling themselves off from any disagreement (Sunstein, 2002). While media fragmentation refers to an increase in the number of available sources of information (Mancini, 2013a) and stands for the actual media choice in any given information environment, polarization denotes the level of partisanship and ideological extremity of the overall media outlets within such political information environments (Fletcher et al., 2019).

In this article, we argue that media polarization and fragmentation at the aggregate level provide favourable opportunity structures for people to seek information in line with their prior beliefs, that is, selective exposure, at the individual level. Drawing on a cross-national survey quasi-experiment on news users from five countries (Switzerland = 794; Denmark = 743; Italy = 936; Poland = 965; United States = 911), we test whether political information environments with different levels of media polarization and fragmentation differ in their ability to facilitate individuals’ selective or congruent political information use. We analyse levels of selective exposure through three distinct measures: actual, perceived and self-reported selective exposure (Goldman and Mutz, 2011; Knobloch-Westerwick and Meng, 2009; Tsfati, 2016). We further investigate whether selective exposure is more frequent among users of more polarizing and fragmenting media sources that provide more choice and possibilities of personalization (Lazer, 2015), such as social media or newspapers, compared with other media types that cater to broader and more politically heterogeneous audiences, such as television and radio (Shehata and Strömbäck, 2018; Van Kempen, 2007).

Our findings show that selective exposure is higher in countries with higher levels of media fragmentation and polarization across two of our three measures of selective exposure. For the participants from less fragmented-polarized political information environments – in other words, those who are less accustomed to large partisan selection options – an interesting behavioural reaction becomes apparent when they are suddenly granted a large selection in the quasi-experimental setting: they seek out attitude-consistent news in greater numbers than those respondents already accustomed to a fragmented-polarized political information environments. Across all groups, we find that selective exposure is – to a certain extent – more common among social media users, while it is slightly less frequent among citizens who use TV, radio and also newspapers as sources of political information. We discuss the implications of our research findings in the conclusion.

Selective exposure

Dating back to the 1940s, selective exposure research has a long tradition (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944). The phenomenon is widely understood as the tendency to select information that is congenial to one’s own individual attitudes and social identities, and its consequences for the democratic process are well documented in the literature (Hart et al., 2009; Iyengar and Hahn, 2009; Sears and Freedman, 1967; Stroud, 2011; Taber and Lodge, 2006).

Whereas seminal studies in persuasive communication argued that increasing selective exposure trends reinforce individuals’ political predispositions and prevent the media from exerting across-the-board effects on people’s cognitions and political attitudes (Iyengar and Hahn, 2009; Klapper, 1960); recent research has demonstrated that exposure to congruent information can be indeed highly consequential. For example, studies based on the United States showed a polarizing effect of exposure to like-minded content (Lelkes et al., 2017; Levendusky, 2013). Selective exposure furthermore reduces the frequency with which people discuss politics with non-like-minded others (Iyengar et al., 2012). Consequently, selective exposure also has tangible consequences for how people perceive their environment: users of opinion-congruent media sources are more inclined to assume that public opinion is in their favour (Dvir-Gvirsman et al., 2018; Wojcieszak, 2008; Wojcieszak and Rojas, 2011). Overall, the use of congruent political information can decrease political tolerance, trigger citizens’ unwillingness to compromise (Stroud, 2011), and leads to the narrowing down of the political agenda to only those more divisive issues of the day (Arceneaux and Johnson, 2013).

The question of what drives individuals’ exposure to like-minded or congruent information is still unsettled, however (Mutz and Young, 2011). Most studies on selective exposure look at either the characteristics of the individuals (e.g. Hart et al., 2009; Knobloch-Westerwick and Meng, 2009; Stroud, 2011) or the information source they have at hand (e.g. Iyengar and Hahn, 2009; Knobloch-Westerwick and Kleinman, 2012; Messing and Westwood, 2014), while research on the contextual factors of selective exposure and on the differences in like-minded media consumption across various political information environments is still scarce (Castro Herrero et al., 2018; Goldman and Mutz, 2011; Mutz and Martin, 2001; Skovsgaard et al., 2016). We elaborate on how such environments can shape patterns of selective exposure in the following section.

Selective exposure in different political information environments

Results of research on selective exposure so far have mainly originated from case studies, most of which focus on the United States. Some of these studies argue that a high-choice media landscape – as it is the case in the United States – facilitates that individuals select news closely aligned with their personal preferences (Prior, 2007). However, the United States is a very particular case in point, where TV channels and radio programmes with distinct partisan orientations are available alongside a number of partisan newspapers and a vivid number of hyper-partisan online sources. A number of scholars have pointed out that the United States is a special case regarding various conditions beyond the shape of the media market, such as the political system and cultural peculiarities (Nechushtai, 2018; Starr, 2012; Stroud, 2011). This raises doubts as to whether results from the US context can be generalized to other countries. The objections are further underlined by the finding that context conditions can influence news usage patterns (overview: Esser and Steppat, 2017). These and other prior findings on media usage from comparative research make it necessary to systematically introduce the concept of the political information environment into the research of selective exposure. Van Aelst et al. (2017) coin the term political information environment as the ‘supply and demand of political news and political information within a certain society’ (p. 4). This concept comprehensively captures both the ability of media in a given country to inform its citizenry as well as how the media and the political systems intertwine and impact people’s political consumption habits. While digitization processes have enabled recipients to select news that is more closely aligned with their personal preferences, not all political information environments offer the same possibilities to consume news that follow individual preferences to the same extent (Aalberg et al., 2013; Esser et al., 2012). Recent research has shown that selective exposure differs depending on the country context (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2019; Tsfati et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the underlying factors have received much less attention. Goldman and Mutz (2011) found that cross-cutting exposure – the counterpart of selective exposure – is more likely to occur in political information environments that are more closely aligned with the political system. By comparing the United States and United Kingdom, as well as newspaper markets in different US counties, Mutz and Martin (2001) found that a more politically aligned media environment with multiple news sources fosters attitude-consistent media exposure. On the other hand, in countries with a strong public broadcaster, people are exposed to more attitude-incongruent political information (Castro Herrero et al., 2018). In this article, we propose two key characteristics of a political information environment that provide more favourable opportunity structures to select congruent news sources: media fragmentation and polarization.

Media fragmentation and polarization as opportunity structures

When media environments become increasingly fragmented, audience preferences matter more to guiding individuals’ choices in media use (Prior, 2007). Mutz and Martin (2001) showed that selective exposure is more likely to occur in more fragmented media markets where there is more than one information source at hand. By contrast, smaller, more saturated media markets are usually characterized by a smaller number of available media outlets, which in turn reduce the choice for potential consumers. Overall, media users can only select media content to match their own views if there is an ample supply of different news sources to choose from and there is no media pulling the majority of users.

Media fragmentation alone, however, is not sufficient for enabling like-minded media use. Equally important is the question of what kind of options audiences can ultimately choose from. Media fragmentation is frequently accompanied by a specialization of media outlets to cater to specific sub-groups of the population (Van Aelst et al., 2017). One way of specialization for media brands is to adhere to audiences’ ideological leanings (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010). When media outlets that are close to one’s political convictions are widespread, users choose those outlets they anticipate as like-minded or congruent, even for non-political content (Iyengar and Hahn, 2009). Outlet specialization based on political ideology results in a stronger polarization of the media market in the sense that media outlets develop closer ties to certain political actors or ideologies and middle-ground media outlets lose market shares to partisan media outlets (Fletcher et al., 2019; Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010; Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Mullainathan and Shleifer, 2005; Van Kempen, 2007). In countries with a high degree of media polarization, citizens are more inclined to choose media according to their political inclination (Goldman and Mutz, 2011; Hallin and Mancini, 2004).

Media users may seek out outlets not only because those outlets share their political viewpoints but also because others with similar views use those outlets as well. Dvir-Gvirsman (2017) understands this media-audience homophily as a way for news users to strengthen their political group identity and as an act of self-expression. A more politically aligned information environment helps users choose those outlets that are closer to other like-minded individuals and, by extension, to their own political convictions (Mutz and Martin, 2001).

Media polarization and fragmentation are hard to separate and hence often go together (Van Aelst et al., 2017). Both trends provide more favourable opportunity structures to engage in attitude-congruent media exposure. We therefore formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: Selective exposure is higher in political information environments with higher levels of media fragmentation and polarization.

In addition to the influence of the macro-level factors of media polarization and fragmentation, we argue that polarization and fragmentation also play out at the media level itself. When it comes to information choices, citizens can choose between different types of media sources. These media types vary in the extent to which they contribute to a more fragmented and polarized public space (Katz, 1996; Nir, 2012) by allowing their users to engage with more specialized content, namely higher amounts of partisan information.

Parallel to the political information environments, Garrett (2009) argues that similar factors play out at the level of media source types, with online media allowing the user to exercise more control over the content they want to use due to a potentially wider and more partisan range of choice compared to other information sources. Consequently, he emphasizes that exercising more control over one’s information environment allows news users to encounter more opinion-congruent content.

Moreover, we argue that media sources that cater to a broader audience, such as many TV channels, offer less opportunities to engage in like-minded news use than media sources that address smaller, more homogeneous audiences for different reasons. Primarily, TV programmes are tailored to reach broad segments of the population independent of their political convictions (Van Kempen, 2007). By catering for larger and by extension more heterogeneous audiences, TV channels also provide more balanced content and higher chances to encounter opposing views (Castro Herrero et al., 2018; Goldman and Mutz, 2011).

Similar to TV, radio does not allow their users to actively search for specific content, but only to watch or listen to a specific programme at a specific time (Clay et al., 2013). Obviously, nowadays, also TV and radio are offering asynchronous information through online channels, although due to production routines and offline programme scheduling their possibilities to tailor programming to specific audiences is still limited. Also, some partisan radio programmes – such as political talk radio in the United States (Stroud, 2008) or religiously affiliated channels in Poland (Krzemiński, 2017) – offer the possibility to engage in selective exposure. However, Clay et al. (2013) stress that even if individuals seek out more partisan programmes, this does not give them agency over ‘the specific issues and events that will be covered in the broadcast’. Furthermore, other studies have demonstrated that TV and radio users expose themselves only to a small degree to opinion-congruent content (LaCour, 2013).

Previous studies have found that compared to most broadcasting media, newspapers offer more opportunities to encounter views similar to one’s own (Goldman and Mutz, 2011). Newspapers in many European countries originated from party-affiliated press, thus providing more politically slanted news than other media types (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). Although direct bonds with political parties have vanished over time, most newspapers have kept an ideological profile to distinguish themselves in the market (Van Kempen, 2007). This is further corroborated by recent studies finding that newspapers are perceived as less hostile and closer to one’s own political convictions than TV (Bachl, 2016). Nevertheless, newspaper journalism still aims to differentiate itself from other non-professional content generators by employing specific journalistic roles and standards, for example, objectivity and disseminator (Banjac and Hanusch, 2020).

While broadcasting media cannot afford to lose audiences because of higher production costs of their programmes, the trademark of most online media is offering more and more possibilities for personalization. On social media, there will be no two users with exactly the same composition of their news feed because of prior user activities, such as clicking on links, following pages and interactions with other users, as well as the setup of friend and follower circles and the information provided by the users themselves (Lazer, 2015). Whereas some scholars argued that the ubiquity of news on social media has increased opportunities for incidental news exposure and learning (Thorson, 2020) and exposure to non-like-minded information (Barberá, 2015), previous research also shows that the so-called social media logic (Shehata and Strömbäck, 2018) enables individuals to tailor content to their specific preferences and needs and easily search and share opinion-congruent information in unprecedented ways. Social media allows users to curate their news feed to their own preferences by following particular news brands (Hahn et al., 2015), political actors sharing their ideology (Barberá, 2015) or through more homogeneous friend circles (Bakshy et al., 2015). Social media users are more fragmented and tend to form ‘communities of interest’ with high inner cohesion (Harrison and Wessels, 2005: 837), since frequent exposure to attitude-incongruent information subsequently leads to opinion-congruent information searching and sharing (Weeks et al., 2017).

Our study complements previous research that compares selective exposure among users of different news media outlets (Goldman and Mutz, 2011; Stroud, 2008) by accounting for newer information sources, such as social media, that provide news users with more favourable opportunity structures to engage in selective exposure. Drawing on the findings presented above, we expect to find the following:

H2: Selective exposure is negatively associated with individual use of TV.

H3: Selective exposure is negatively associated with individual use of radio.

H4: Selective exposure is positively associated with individual use of newspapers.

H5: Selective exposure is positively associated with individual social media use for news.

Case selection

We selected our cases to parallel the notion of more and less fragmented-polarized political information environments. Despite current political information environments offering unprecedented opportunities to choose political information and engage in news consumption – in particular through new digital technologies that facilitate news use – some countries offer more favourable opportunities than others for across-the-board selective exposure patterns to unfold. By choosing countries that differ in terms of the level at which media fragmentation and polarization are prevalent, this selection allows us to draw conclusions about the influence of these two phenomena on selective exposure.

As a first set of countries, we identified Italy, Poland and the United States. These three countries have relatively large media markets that allow news organizations to make specialized offerings for different audiences. In the United States, public service broadcasting (PSB) traditionally plays only a peripheral role; in Poland, we see an ever more similar picture. Furthermore, PSB in Poland and Italy is influenced by government and political parties (Esser et al., 2012; Newman et al., 2019). An additional case in point for the polarized character of the three countries’ media markets is that partisan news sources are strong in Italy, Poland, and the United States (Mancini, 2013b; Mocek, 2019; Nechushtai, 2018). In the United States, the success of bluntly partisan media outlets, especially in the realms of cable TV, radio and online, reflects on the rising political polarization within the country (Hall Jamieson and Cappella, 2008; Iyengar and Hahn, 2009). In Poland, both public and commercial news outlets are closely entangled with political actors (Mocek, 2019); similarly, in Italy, ties between the media and the political world remain strong (Mancini, 2009).

The second set of countries, Denmark and Switzerland, share many characteristics as well. First, they are both small in size, and to maintain media plurality, the state directly and indirectly subsidizes the media sector (Trappel, 2018). The public service broadcaster traditionally has a very strong position in both countries and is the most frequently used news source for many citizens (Newman et al., 2019). Denmark and Switzerland have a history of partisan media, especially in the press (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). Nowadays, however, non-ideological media prevail (Marquis et al., 2011; Nord, 2008).

Because countries differ in their levels of media fragmentation and polarization, we identified five indicators – three for fragmentation and two for polarization – to illustrate our classification and build a calibrated measure. First, fragmentation can be understood as a function of the media market size (Lowe and Nissen, 2011). The more sizable a national media market is, the better the opportunities are for a larger number of media outlets to operate in an economically sustainable way (Picard, 2011). In more sizable media markets, partisan media outlets and more independent and balanced outlets exist side by side (Gentzkow et al., 2006).

Another indicator for fragmentation is PSB share among national audiences for political information. Katz (1996) observes that with the liberalization of the TV market, societies are in danger of losing social cohesion and becoming increasingly fragmented because audiences are being divided into smaller group of users. To secure larger audiences, PSB-based systems are more independent from market demands and more generously funded (Iyengar et al., 2010). Thus, PSB does not address fringe audiences but instead aims at addressing the general public. Where there is a strong PSB, the market is more saturated, leaving smaller shares of the audience for other news outlets (Castro Herrero et al., 2018; McQuail, 1992). A weak position of the PSB thus indicates higher levels of media market fragmentation. Since market share measures differ substantially between the countries, we used the weekly audience share of the Reuters Digital News Report 2019 as a proxy (Newman et al., 2019).

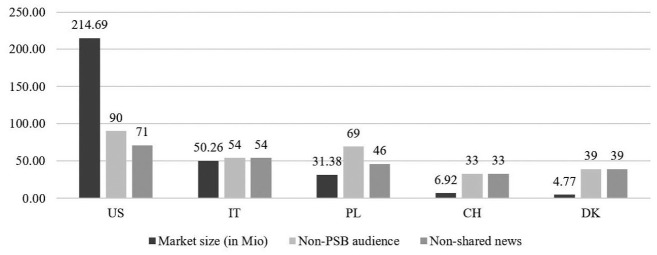

Understanding fragmentation as lack of a common frame of reference, Nir (2012) defined it as the absence of shared news. This indicator differs from the former to the extent that shared news is not limited to the PSB but includes other media types as well, including online sources. This indicator is important because PSB is not the most used source in many countries. There are other media outlets that have an equally catch-all approach to inform large segments of the public. According to Nir (2012), a higher proportion of shared news ‘helps larger segments catch up with the news, and facilitates fewer disparities between groups’ (p. 581). Based on the Reuters Digital News Report 2019, we looked at the average weekly usage share of the most frequently used news outlet in each of our five countries (Newman et al., 2019). 1 Switzerland and Denmark demonstrate the highest levels of shared news, with PSB attracting a majority of the user population for news (see Figure 1). However, also other traditional legacy media outlets engage substantial parts of the user population for news (Newman et al., 2019). On all the three indicators, the United States proves to be an extreme outlier and is most closely followed by Italy and Poland.

Figure 1.

Three indicators of media fragmentation.

(1) Market size refers to the proportion of population above 14 years old that uses news on a regular basis. (2) Non-PSB audience refers to the share other (private) TV stations have on the market apart from the main PSBs. (3) Non-shared news refers to the proportion of news users not using the main news media outlet in the respective countries.

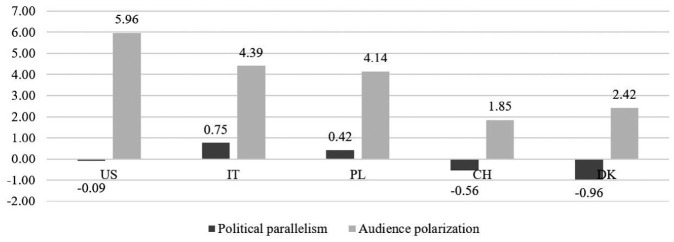

Media polarization is measured through two indicators. First we looked at political parallelism because where media outlets are closely related to political parties, selection processes based on political ideology are more likely to take place (Goldman and Mutz, 2011; Mutz and Martin, 2001). Replicating Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) seminal work on media systems, Brüggemann et al. (2014) used data from various sources to provide an empirical test for the categorization of media systems. As one indicator to differentiate media systems, Hallin and Mancini (2004) identify political parallelism. To operationalize this dimension, Brüggemann et al. (2014) looked at different indicators, such as journalists’ political attitudes, media content bias and vicinity of media outlets with political parties. The standardized coefficients indicate that in Italy and Poland, the media system is most closely intertwined with the political system (Brüggemann et al., 2014; Castro Herrero et al., 2017). This is represented in Figure 2 with the dark bars.

Figure 2.

Two indicators of media polarization.

(1) Political parallelism is a standardized measure taking into account the following categories: amount of commentary, partisan policy, journalists’ political orientation, media-party parallelism, political bias and PSB dependency. (2) Audience polarization takes into account the average distance of the political orientation from the audience of the five most used news outlets per media type from the average political orientation in each country (as weighted by audience share).

As a last measure of media polarization, we looked at audience polarization at the news outlets level. For this, we calculated the ideological extremity of media outlets and how far apart their political alignments are. To this end, we considered the five most used media outlets per country for five different media source types (television, radio, print, digital-born online news and blogs) and calculated how far the respective audiences diverge on average from the population mean in the respective country (Fletcher et al., 2019). 2 We combined these individual scores for outlet extremity into an average divergence score of all the outlets and weighted it by outlet audience share. 3 As shown in Figure 2, the United States scores highest in media ideological extremity, while Denmark and Switzerland show comparatively low values (see the light bars in Figure 2).

Method

Sample

We conducted a two-wave online survey quasi-experiment through an internationally renowned market research institute in five countries – Denmark (n = 743), Italy (n = 936), Poland (n = 965), the United States (n = 911) and Switzerland (n = 794) – among news users aged 18–69 years (N = 4349). The participants had to indicate whether they were current residents in one of the five countries to ensure they were being exposed to national news outlets. The first questionnaire (wave 1) was sent out in July 2018, and the second (wave 2) was sent 4 weeks after to all participants who finished the first wave (response rate: 33.3%). The sample is nearly evenly split between females (50.9%) and males (49.1%). The average age is 49 years (SD = 13.9). Most of the participants had completed some form of secondary education (47.2%).

Measures

Self-reported selective exposure

To measure selective exposure in the most direct way, we used items from Tsfati’s (2016) scale to measure the tendency for selecting ideologically congruent political information, and we added additional items for a more comprehensive measurement (see Supplemental Appendix). Tapping into different aspects of exposure to congruent information, the participants indicated how strongly they agreed with different statements regarding their use of information sources on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘does not apply at all’ to 5 = ‘absolutely applies’). The eight-item scale displayed a high reliability score (Cronbach’s α = .839) (M = 2.99, SD = .850).

Perceived selective exposure

We asked the participants to rate all news outlets they reportedly use on a standard left–right ideological scale (Goldman and Mutz, 2011). These scores were later subtracted from the participants’ own self-placement on the same left–right scale and combined into a mean score index. To facilitate interpretation, we inverted the scores, so high numbers indicate high agreement between the political position of users and their media sources. The scale, composed of five items, reached an excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = .914) (M = 7.21, SD = 1.731).

Actual selective exposure

Our third selective exposure measure was adopted from Knobloch-Westerwick and Meng (2009). We created an online news magazine (see Supplemental Appendix: Figure 4) with eight different articles on four political topics (free trade, privacy, migration and penalty reform). The four topics were pretested in a pilot study. Each article had a clear stance towards or against the issue at hand. The articles were perceived as equally interesting. In the first wave, the participants were asked whether they supported or opposed every issue on a sliding scale ranging from 1 (e.g. ‘I see more risks than opportunities resulting from free trade and free markets for our country’) to 101 (e.g. ‘I see more opportunities than risks resulting from free trade and free markets for our country’). 4 In the second wave, article selection was unobtrusively tracked and later matched with the political attitude towards the issue, resulting in a number for consonant and another number for dissonant article choices. 5 We subtracted the number of consonant articles from the number of dissonant articles and divided the resulting number by the total number of articles the participants read. Positive numbers indicate a more congruent article choice, while negative numbers stand for a higher exposure to dissonant views. On average, the participants tended to select more congruently than dissonantly (M = .10, SD = .541).

Levels of fragmentation and polarization in the media environments

To account for country differences, a joint measure of media fragmentation and polarization was constructed using the five indicators reported in Figures 1 and 2. For each indicator, we ranked the five political information environments according to their values on the five indicators. We calculated a mean score index of the five indicators. To facilitate interpretation, we inverted its scores, meaning that higher numbers stand for higher levels of media fragmentation and polarization (Switzerland = 1.42; Denmark = 1.42; Poland = 3.42; Italy = 4.09; United States = 4.5).

Use of media sources

Media usage was assessed via a dichotomous choice (1 for ‘use’, 0 for ‘no use’). We asked participants which media source types they have used at least once in the past 7 days to obtain information on current political events. They could select from four different media source types (TV, radio, newspaper and social media). 6 The participants were free to choose multiple media sources.

Political interest

The participants indicated how interested they were generally in politics on a scale from 1 (not at all interested) to 5 (very interested) (M = 3.25, SD = 1.186).

Left–right self-placement

To indicate their political orientation, the participants placed themselves on a standard left–right 11-point scale ranging from 1 (clearly to the left) to 11 (clearly to the right) (M = 6.17, SD = 2.79).

Extremity

Political extremity was obtained by folding the scale for left–right self-placement (M = 2.27, SD = 1.59).

User socio-demographics

We controlled for sex, age and education. Because the educational systems differ greatly across countries, education was measured through three categories: primary, secondary and tertiary education (ESS, 2017; NAES, 2008).

Results

Cross-country differences in selective exposure

We begin with a brief overview of how far-reaching the phenomenon of selective exposure is in the five countries under study. We conducted analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) using the three distinct selective exposure measures as dependent variables to test for country differences among our five cases. 7

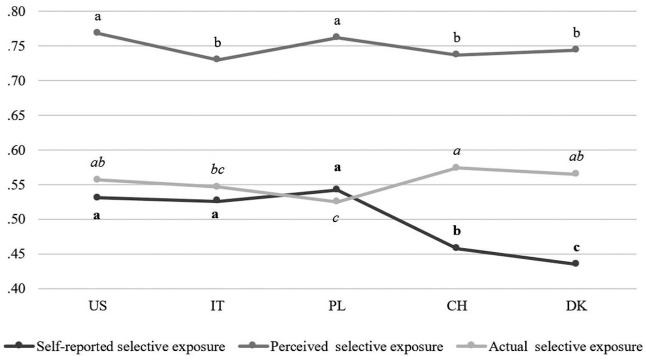

First, we find only a slight preference for selective exposure among all the participants for self-reported selective exposure (M = .510, SD = .206). 8 However, looking at the preference for opinion-congruent content by country, we find important differences in our self-reported selective exposure measure across the five cases: in Denmark (M = .435, SD = .008) and Switzerland (M = .458, SD = .008), individuals’ preferences for pro-attitudinal information sources are significantly lower than those in the other three countries. Among participants from the United States (M = .531, SD = .010), Italy (M = .526, SD = .007) and Poland (M = .542, SD = .007), the preference for pro-attitudinal information is more pronounced (Figure 3, dark grey line).

Figure 3.

Cross-country differences for three selective exposure measures (ANCOVA).

Predicted average levels of self-reported, perceived and actual selective exposure by country. All three selective exposure measures were rescaled on a 0–1 scale to make them comparable. (1) Self-reported SE: F(4, 3448) = 32.44, p < .001, η2 = .036. (2) Perceived SE: F(4, 3080) = 6.32, p < .001, η2 = .008. (3) Actual SE: F(4, 3465) = 3.43, p < .01, η2 = .004. Groups with different identification letters (a, b, c) are significantly different according to Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests (p < .05).

Second, individuals across all five countries score higher on perceived selective exposure compared with the other two measures (M = .721, SD = .173). This indicates a generally high level of perceived consonance in the users’ daily news diets. Looking at the country differences in the ANCOVA, Polish (M = .762, SD = .006) and US participants (M = .768, SD = .008) perceive even more opinion-congruent reporting when they think of their most frequently used news sources compared with the other participants (see Figure 3, medium grey line).

Third, although the participants chose significantly more often articles that are in line with their political attitudes across all countries (M = .553, SD = .263; t(4348) = 12.62, p < .001), we find relevant country differences in levels of actual selective exposure. Danish (M = .565, SD = 0.011) and Swiss news users (M = .574, SD = .010) were particularly selective in matching their article choice with their political convictions, while Polish participants (M = .525, SD = .010) chose news articles that are in line with their prior political attitudes significantly less often (see Figure 3, light grey line).

Fragmented-polarized media environments and selective exposure

After this overview, we now turn to Table 1 and the questions of what influence highly fragmented and polarized media environments have on selective exposure patterns. 9 Our hypothesis states that citizens who live in political information environments with higher media fragmentation and polarization would show higher levels of selective exposure. Our results confirm our H1 (see Table 1) 10 that a more polarized-fragmented political information environment has a positive influence on participants’ self-reported tendency to select congruent information sources over dissonant ones (β = .405, p < .001). As for perceived selective exposure, perceived agreement with the position of the media is higher in countries with higher media fragmentation and polarization (β = .204, p < .05), thus confirming our H1.

Table 1.

Bootstrapped OLS regression with three selective exposure measures.

| Self-reported selective exposure | Perceived selective exposure | Actual selective exposure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | |

| (Constant) | 2.479 | .086 | 9.251 | .295 | .057 | .074 |

| Sex (baseline male) | .030 | .021 | .018† | .010 | −.012 | .021 |

| Age | .000 | .002 | .001 | .002 | .002* | .001 |

| Education | .033 | .031 | .097 | .066 | −.031** | .010 |

| Political interest | .033* | .013 | .057* | .026 | −.013* | .007 |

| Political orientation | .004 | .005 | −.075† | .027 | .015*** | .002 |

| Political extremity | .083*** | .076 | −.655*** | .042 | .012* | .005 |

| Predictors #1 - #4 | ||||||

| #1 Users in more fragmented-polarized media environments | .405*** | .059 | .204* | .099 | −.047* | .024 |

| #2 TV user | −.092 | .062 | −.137 | .095 | −.066** | .024 |

| #3 Radio user | −.014 | .023 | −.013 | .091 | −.021* | .082 |

| #3 Newspaper user | −.042† | .025 | −.063 | .097 | .022 | .027 |

| #4 Social media user | .073* | .029 | −.02 | .037 | −.017 | .011 |

| N | 2812 | 2560 | 2825 | |||

| R 2 | .101 | .270 | .018 | |||

| F | 299.48*** | 804.78*** | 51.04*** | |||

OLS: ordinary least squares.

Estimates are unstandardized coefficients (B) with standard errors (SE B).

p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, †p < .1 (two-tailed).

So far, the results for the different selective exposure measures display a concordant image, providing support for our hypothesis. Interestingly, for the third measurement (actual selective exposure), we find a negative coefficient (β = −.047, p < .05). At first glance, this unexpected finding implies that the less fragmented-polarized the political information environment from which the respondent originates, the stronger the quasi-experimentally measured behavioural disposition for attitude-consistent news selection is. Put differently, it is the participants from less fragmented-polarized political information environments who chose more congruent articles on the mocked news site. To delve deeper into this finding, we compared the extent of self-reported selective exposure with actual selective exposure through the quasi-experimental condition that was carried out in further analyses. A series of t tests confirmed that the average actual selective exposure (M = .566; SD = .265) is significantly greater than self-reported selective exposure (M = .435; SD = .202) for individuals in non-polarized countries (t(1201) = 21.725, p < .001). This is not the case for citizens in fragmented-polarized information environments (t(1950) = 1.547, p = .122). 11 We will come back to this peculiar behaviour of the Danish and Swiss participants in the discussion. 12

Turning now to answering H2 and H3, users of broadcasting media engage in less selective exposure. Results indicate that TV (β = −.066, p < .01) and radio users (β = −.021, p < .05) are less likely to engage in actual selective exposure. While contrary to our expectations in H4, also newspaper users self-report slightly less selective exposure (β = −.042, p = .09).

Results further show only limited support for the assumption made in H5, that social media users are more likely to engage in selective exposure. Only for self-reported selective exposure, we find that social media users prefer like-minded news (β = .073, p < .05). 13

Discussion

In this study, we investigated how widespread selective exposure is among news users in five different countries whose political information environments provide different opportunity structures to engage in attitude-congruent information choices. Overall, we find a general preference among media users for selecting messages that are consistent with their attitudes, albeit with different intensities across countries and media types.

First, selective exposure is higher in countries with a more fragmented-polarized political information environment, at least when it comes to self-reported and perceived selective exposure. Interestingly enough, these perceptions and preferences do not manifest in actual choice. We find that the citizens from political information environments that allow for less selective exposure engage in more opinion-congruent source choices when given vast opportunities to self-select through a quasi-experimental condition. The citizens from Denmark and Switzerland were among those who chose the most attitude-congruent from all countries. At first glance, this finding may seem surprising. However, this is not so if we understand their political information environments as an inhibiting factor to exercising congruent media exposure. When given the same conditions as countries with already more fragmented-polarized political information environments, they make greater use of these unprecedented choices. To draw on an analogy from consumer behaviour, consider the following: imagine a less fragmented, less polarized political information landscape is like a small convenience store where there is a clear product range and where the consumer has little product choice. Now, imagine we put the same customer of the small convenience store in a big, suburban hypermarket with a variety of products never seen before. It is very likely that the convenience store customer will fill his or her shopping cart with all the products he or she cannot find in the convenience store around the corner, while the hypermarket regular customer will only take the products he or she always buys.

Second, we looked at different types of media sources that are said to contribute in different ways to selective exposure patterns: social media, newspapers, radio and TV. Our results provide only limited support for the assumption that audiences of broadcasting media are less selective compared to newspaper and social media users. Our findings indeed seem to go in line with recent studies showing that social media allows for some degree of cross-cutting exposure through incidental exposure (Barberá, 2015) and that online audiences are not necessarily more fragmented than offline news users (Fletcher and Nielsen, 2017).

Our analysis is not without shortcomings. Future research may make use of online tracking data to look at frequent selective exposure from a greater number of individuals in different country contexts (Stier et al., 2020). In addition, our methodological design does not allow to test for the potential bi-directional nature of the process at hand, in the sense that media use behaviours might not only be influenced by factors in the media environment, but that ultimately media use behaviours also influence the way the media market is composed. Furthermore, our analysis takes into account the differences in media systems, namely the levels of media polarization and fragmentation. There might be other factors at play driving the extent of selective exposure at the country level. Other studies have identified the differences in the political system or economic setup of the media market as predictors for different media use outcomes (Iyengar et al., 2010; Wessler and Rinke, 2014).

Our study attests to the fact that research on media polarization and fragmentation can serve as a crucial explanatory factor for cross-national research on media use behaviours. Three points are important in this respect. First, our study shows that media fragmentation and polarization are enabling opportunity structures for media users to engage in selective exposure.

Second, our study is one of the first to compare the United States with other Western countries on a set of three separate measures of selective exposure. Our data support the commonly held assumption that selective exposure is relatively high in the United States but also reveal that it is not always the highest. We find that citizens from countries with more inclusive political information environments are the least likely to engage in selective exposure in their daily news use. The results speak for the more unifying character of certain political information environments, as demonstrated by prior studies (Castro Herrero et al., 2018; Nir, 2012), shedding light on the importance to test empirical findings on media use outside the United States.

This brings us to our third point. Our study shows that political information environments are important influences for preferences for and perceptions of like-minded news exposure. These environments are also influencing behaviours but not as we expected initially. We anticipated that a more fragmented-polarized political information environment would have a constant and consistent effect on the choice behaviours of news users. When creating equal opportunities to self-select under quasi-experimentally manipulated conditions, it is those participants who are less able to enjoy an exuberant media selection at home (Switzerland, Denmark) who show a stronger behavioural disposition for selecting opinion-congruent information. News users from these two countries, who may be less familiar with lavish, highly partisan news sources, are more susceptive to opinion-congruent choices than citizens from countries where these partisan sources can be found in their everyday news use. Thus, political information environments matter in people’s media use in three distinct ways: by forming preferences, shaping perceptions, and guiding behaviour.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ejc-10.1177_02673231211012141 for Selective exposure in different political information environments – How media fragmentation and polarization shape congruent news use by Desiree Steppat, Laia Castro Herrero and Frank Esser in European Journal of Communication

To determine the single most frequently used news source in any given country, we considered both online and offline news media outlets with the highest reach in each given country according to Newman et al. (2019) and selected the news source with the highest audience share of weekly users.

We followed Fletcher et al. (2019) in using ideological extremity of different media outlets’ audiences to make inferences on media polarization at the supply side. Similarly, we used audience share of different outlets as a proxy of media fragmentation, as it is customary (Mancini, 2013a). Note that both concepts (audience concentration and polarization) and their derived operationalizations are methodologically and substantively different from selective exposure. Selective exposure refers to the extent to which people seek like-minded information in their frequent media diets, irrespectively of how politically extreme these diets might be, and above and beyond other individual factors (issue interest, political sophistication) that can lie behind levels of media fragmentation at the aggregate level.

Hence, outlets with low divergence from the population mean and a more sizable audience weigh more heavily than small outlets with high divergence from the average political orientation.

Participants with no clear preference for any side were excluded from the analysis (N = 67).

More information about the quasi-experimental part of this study can be found in the Supplemental Appendix.

For TV, radio and newspaper use, we clarified for participants that we did not differentiate between news programmes and content that was consumed online or offline. For example, for TV use, we asked whether they used news shows on TV (regardless of whether on a TV set, media device and/or app).

All three models are controlled for sex, age, education, political interest, political orientation, political extremity and media use. The means used to run analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) are corrected by the effect of these covariates.

All three selective exposure measures were rescaled on a 0–1 scale to make them comparable.

We tested whether media fragmentation and polarization have different effects if included separately into a regression model. Models with only one of the two predictors (referred to as model 1 for media fragmentation and model 2 for media polarization as predictors from now onward) have less explanatory power as compared to the models that include both predictors combined in an index variable – referred to as model 3 (self-reported selective exposure: R2Model1 = .057, R2Model2 = .060, R2Model3 = .101; perceived selective exposure: R2Model1 = .139, R2Model2 = .140, R2Model3 = .270; actual selective exposure: R2Model1 = .011, R2Model2 = .011, R2Model3 = .018).

To account for the small number of level 2 units (five countries), we follow the approach suggested by Huang (2018) and estimated cluster bootstrapped regressions with 1000 replications (clustered on countries) using the bootcov function in the rms: Regression Modelling Strategies package by Harrell (2019) in R.

As a side note, we add that perceived selective exposure is invariably higher across all countries.

We have conducted additional analyses to test the individual influence of media fragmentation and polarization separately. Results reveal that only both factors combined have an effect on selective exposure (available from the authors).

Additional testing with a split sample revealed no country-specific patterns concerning the effect of using different kind of media source types on any of the three selective exposure measures.

Footnotes

Authors note: Laia Castro Herrero is also affiliated with Universitat International de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation [project grant number: 100017_173286].

ORCID iD: Desiree Steppat https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2403-9797

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Desiree Steppat, University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Laia Castro Herrero, University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Frank Esser, University of Zurich, Switzerland.

References

- Aalberg T, Blekesaune A, Elvestad E. (2013) Media choice and informed democracy: Toward increasing news consumption gaps in Europe? The International Journal of Press/Politics 18(3): 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Arceneaux K, Johnson M. (2013) Changing Minds or Changing Channels? Partisan News in an Age of Choice. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachl M. (2016) Selective exposure and hostile media perceptions during election campaigns. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 91(4): 352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Bakshy E, Messing S, Adamic LA. (2015) Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348(6239): 1130–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banjac S, Hanusch F. (2020) A question of perspective: Exploring audiences’ views of journalistic boundaries. New Media & Society 20(7): 2450–2468. [Google Scholar]

- Barberá P. (2015) Birds of the same feather tweet together: Bayesian ideal point estimation using Twitter data. Political Analysis 23(1): 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann ML, Engesser S, Büchel F, et al. (2014) Hallin and Mancini revisited: Four empirical types of Western media systems. Journal of Communication 64(6): 1037–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Herrero L, Humprecht E, Engesser S, et al. (2017) Rethinking Hallin and Mancini beyond the west: An analysis of media systems in central and eastern Europe. International Journal of Communication 11(27): 4797–4823. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Herrero L, Nir L, Skovsgaard M. (2018) Bridging gaps in cross-cutting media exposure: The role of public service broadcasting. Political Communication 35(4): 542–565. [Google Scholar]

- Clay R, Barber JM, Shook NJ. (2013) Techniques for measuring selective exposure: A critical review. Communication Methods and Measures 7(3-4): 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Dvir-Gvirsman S. (2017) Media audience homophily: Partisan websites, audience identity and polarization processes. New Media & Society 19(7): 1072–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Dvir-Gvirsman S, Kelly Garrett R, Tsfati Y. (2018) Why do partisan audiences participate? Perceived public opinion as the mediating mechanism. Communication Research 45(1): 112–136. [Google Scholar]

- ESS (2017) European Social Survey (ESS), Round 8 – 2016: NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round8/survey/ESS8_appendix_a1_e02_3.pdf

- Esser F, Steppat D. (2017) News media use: International comparative research. In: Rössler P, Hoffner CA, van Zoonen L. (eds) The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. Chichester; Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Esser F, de Vreese CH, Strömbäck J, et al. (2012) Political information opportunities in Europe: A longitudinal and comparative study of thirteen television systems. The International Journal of Press/Politics 17(3): 247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R, Nielsen RK. (2017) Are news audiences increasingly fragmented? A cross-national comparative analysis of cross-platform news audience fragmentation and duplication. Journal of Communication 67(4): 476–498. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R, Cornia A, Nielsen RK. (2019) How polarized are online and offline news audiences? A comparative analysis of twelve countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25(2): 69–195. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett RK. (2009) Politically motivated reinforcement seeking: Reframing the selective exposure debate. Journal of Communication 59(4): 676–699. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzkow MA, Shapiro JM. (2010) What drives media slant? Evidence from U.S. daily newspapers. Econometrica 78(1): 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzkow MA, Glaeser EL, Goldin C. (2006) The rise of the fourth estate: How newspapers became informative and why it mattered. In: Glaeser EL, Goldin C. (eds) Corruption and Reform. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 187–230. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman SK, Mutz DC. (2011) The friendly media phenomenon: A cross-national analysis of cross-cutting exposure. Political Communication 28(1): 42–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn KS, Ryu S, Park S. (2015) Fragmentation in the Twitter following of news outlets: The representation of South Korean users’ ideological and generational cleavage. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92(1): 56–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Jamieson K, Cappella JN. (2008) Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallin DC, Mancini P. (2004) Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. (2019) rms: Regression modeling strategies. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html.

- Harrison J, Wessels B. (2005) A new public service communication environment? Public service broadcasting values in the reconfiguring media. New Media & Society 7(6): 834–853. [Google Scholar]

- Hart W, Albarracín D, Eagly AH, et al. (2009) Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychological Bulletin 135(4): 555–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FL. (2018) Using cluster bootstrapping to analyze nested data with a few clusters. Educational and Psychological Measurement 78(2): 297–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, Hahn KS. (2009) Red media, blue media: Evidence of ideological selectivity in media use. Journal of Communication 59(1): 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, Curran J, Lund AB, et al. (2010) Cross-national versus individual-level differences in political information: A media systems perspective. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 20(3): 291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, Sood G, Lelkes Y. (2012) Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly 76(3): 405–431. [Google Scholar]

- Katz E. (1996) And deliver us from segmentation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 546(1): 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper JT. (1960) The Effects of Mass Communication: An Analysis of Research on the Effectiveness and Limitations of Mass Media in Influencing the Opinions, Values, and Behavior of Their Audiences. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Westerwick S, Kleinman SB. (2012) Preelection selective exposure: Confirmation bias versus informational utility. Communication Research 39(2): 170–193. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Westerwick S, Meng J. (2009) Looking the other way: Selective exposure to attitude-consistent and counterattitudinal political information. Communication Research 36(3): 426–448. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Westerwick S, Liu L, Hino A, et al. (2019) Context impacts on confirmation bias: Evidence from the 2017 Japanese snap election compared with American and German findings. Human Communication Research 41(3): 427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Krzemiński I. (2017) Radio Maryja and Fr. Rydzyk as a creator of the national-catholic ideology. In: Ramet SP. (ed.) Religion, Politics, and Values in Poland: Community and Change Since 1989. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- LaCour MJ. (2013) A Balanced Information Diet, Not Selective Exposure: Evidence from Erie to Arbitron. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2319161

- Lazarsfeld PF, Berelson B, Gaudet H. (1944) The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. [Google Scholar]

- Lazer D. (2015) Social sciences: The rise of the social algorithm. Scandinavian Political Studies 348(6239): 1090–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelkes Y, Sood G, Iyengar S. (2017) The hostile audience: The effect of access to broadband Internet on partisan affect. American Journal of Political Science 61(1): 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Levendusky MS. (2013) Why do partisan media polarize viewers? American Journal of Political Science 57(3): 611–623. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe GF, Nissen CS. (eds) (2011) Small among Giants: Television Broadcasting in Smaller Countries. Göteborg: Nordicom. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail D. (1992) Media Performance: Mass Communication and the Public Interest. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini P. (2009) Il Sistema Fragile: I Mass Media in Italia Tra Politica E Mercato (The Fragile System: Mass Media in Italy between Politics and Marketplace). Roma: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini P. (2013. a) Media fragmentation, party system, and democracy. The International Journal of Press/Politics 18(1): 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini P. (2013. b) The Italian public sphere: A case of dramatized polarization. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 18(3): 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis L, Schaub H-P, Gerber M. (2011) The fairness of media coverage in question: An analysis of referendum campaigns on welfare state issues in Switzerland. Swiss Political Science Review 17(2): 128–163. [Google Scholar]

- Messing S, Westwood SJ. (2014) Selective exposure in the age of social media: Endorsements Trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Communication Research 41(8): 1042–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Mocek S. (2019) A map of political discourse regarding Polish public service media. In: Połońska E, Beckett C. (eds) Public Service Broadcasting and Media Systems in Troubled European Democracies. Cham: Springer, pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mullainathan S, Shleifer A. (2005) The market for news. American Economic Review 95(4): 1031–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz DC, Martin PS. (2001) Facilitating communication across lines of political difference: The role of mass media. American Political Science Review 95(1): 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz DC, Young L. (2011) Communication and public opinion: Plus Ca change? Public Opinion Quarterly 75(5): 1018–1044. [Google Scholar]

- NAES (2008) National Annenberg Election Survey 2008 Phone Edition (NAES08-Phone). Philadelphia, PA: NAES. [Google Scholar]

- Nechushtai E. (2018) From liberal to polarized liberal? Contemporary U.S. news in Hallin and Mancini’s typology of news systems. The International Journal of Press/Politics 23(2): 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Newman N, Richard F, Antonis K, et al. (2019) Reuters Institute digital news report 2019. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/DNR_2019_FINAL_1.pdf (accessed 26 July 2019).

- Nir L. (2012) Public space: How shared news landscapes close gaps in political engagement. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 56(4): 578–596. [Google Scholar]

- Nord L. (2008) Comparing Nordic media systems: North between West and East? Central European Journal of Communication 1(1): 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Picard RG. (2011) Broadcast economics, challenges of scale, and country size. In: Lowe GF, Nissen CS. (eds) Small among Giants: Television Broadcasting in Smaller Countries. Göteborg: Nordicom, pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Prior M. (2007) Post-broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sears DO, Freedman JL. (1967) Selective exposure to information: A critical review. Public Opinion Quarterly 31(2): 194. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata A, Strömbäck J. (2018) Learning political news from social media: Network media logic and current affairs news learning in a high-choice media environment. Communication Research 48(1): 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Skovsgaard M, Shehata A, Strömbäck J. (2016) Opportunity structures for selective exposure: Investigating selective exposure and learning in Swedish election campaigns using panel survey data. The International Journal of Press/Politics 21(4): 527–546. [Google Scholar]

- Starr P. (2012) An unexpected crisis. The International Journal of Press/Politics 17(2): 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Stier S, Kirkizh N, Froio C, et al. (2020) Populist attitudes and selective exposure to online news: A cross-country analysis combining Web tracking and surveys. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25(3): 426–446. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud NJ. (2008) Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior 30(3): 341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud NJ. (2011) Niche News: The Politics of News Choice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein CR. (2002) Republic.com. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taber CS, Lodge M. (2006) Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science 50(3): 755–769. [Google Scholar]

- Thorson K. (2020) Attracting the news: Algorithms, platforms, and reframing incidental exposure. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 21(8): 1067–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Trappel J. (2018) Subsidies: Fuel for the Media. In: d’Haenens L, Sousa H, Trappel J. (eds) Comparative Media Policy, Regulation and Governance in Europe: Unpacking the Policy Cycle. Bristol: Intellect, pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tsfati Y. (2016) A new measure for the tendency to select ideologically congruent political information: Scale development and validation. International Journal of Communication 10: 200–225. [Google Scholar]

- Tsfati Y, Stroud NJ, Chotiner A. (2014) Exposure to ideological news and perceived opinion climate: Testing the media effects component of spiral-of-silence in a fragmented media landscape. The International Journal of Press/Politics 19(1): 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- van Aelst P, Strömbäck J, Aalberg T, et al. (2017) Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association 41(1): 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen H. (2007) Media-party parallelism and its effects: A cross-national comparative study. Political Communication 24(3): 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks BE, Lane DS, Kim DH, et al. (2017) Incidental exposure, selective exposure, and political information sharing: Integrating online exposure patterns and expression on social media. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22(6): 363–379. [Google Scholar]

- Wessler H, Rinke EM. (2014) Deliberative performance of television news in three types of democracy: Insights from the United States, Germany, and Russia. Journal of Communication 64(5): 827–851. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszak M. (2008) False consensus goes online: Impact of ideologically homogeneous groups on false consensus. Public Opinion Quarterly 72(4): 781–791. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszak M, Rojas H. (2011) Hostile public effect: Communication diversity and the projection of personal opinions onto others. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 55(4): 543–562. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ejc-10.1177_02673231211012141 for Selective exposure in different political information environments – How media fragmentation and polarization shape congruent news use by Desiree Steppat, Laia Castro Herrero and Frank Esser in European Journal of Communication