Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests that the detrimental effect of nicotine and tobacco smoke on the central nervous system (CNS) is caused by the neurotoxic role of nicotine on blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression, and the dopaminergic system. The ultimate consequence of these nicotine associated neurotoxicities can lead to cerebrovascular dysfunction, altered behavioral outcomes (hyperactivity and cognitive dysfunction) as well as future drug abuse and addiction. The severity of these detrimental effects can be associated with several biological determinants. Sex and age are two important biological determinants which can affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of several systemically available substances, including nicotine. With regard to sex, the availability of gonadal hormone is impacted by the pregnancy status and menstrual cycle resulting in altered metabolism rate of nicotine. Additionally, the observed lower smoking cessation rate in females compared to males is a consequence of differential effects of sex on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nicotine. Similarly, age-dependent alterations in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nicotine have also been observed. One such example is related to severe vulnerability of adolescence towards addiction and long-term behavioral changes which may continue through adulthood. Considering the possible neurotoxic effects of nicotine on the central nervous system and the deterministic role of sex as well as age on these neurotoxic effects of smoking, it has become important to consider sex and age to study nicotine induced neurotoxicity and development of treatment strategies for combating possible harmful effects of nicotine. In the future, understanding the role of sex and age on the neurotoxic actions of nicotine can facilitate the individualization and optimization of treatment(s) to mitigate nicotine induced neurotoxicity as well as smoking cessation therapy. Unfortunately, however, no such comprehensive study is available which has considered both the sex- and age-dependent neurotoxicity of nicotine, as of today. Hence, the overreaching goal of this review article is to analyze and summarize the impact of sex and age on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nicotine and possible neurotoxic consequences associated with nicotine in order to emphasize the importance of including these biological factors for such studies.

Keywords: nicotine, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, sex, age, neurotoxicity

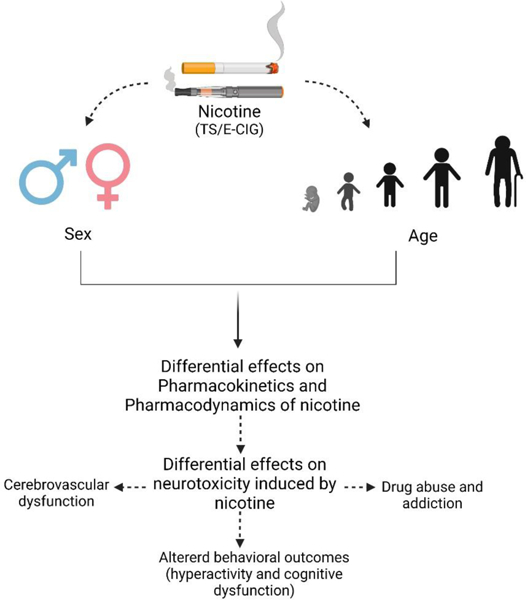

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction:

Tobacco smoking has been identified as one of the major health concerns for several decades. Smoking is a major contributor to both long term disability and harm to several organs of the body causing various diseases including but not limited to cancer, stroke, heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [1] . It remains the leading cause of preventable death in the US [2]. More than 16 million Americans are suffering from a disease caused by smoking [1] and each year more than 7 million people die worldwide due to smoking [3] . If global smoking patterns continue at this rate, it is assumed that more than 8 million people will die yearly from diseases associated with tobacco smoke by 2030 [1]. Fortunately, in the US, the number of smokers declined in the 1970s and 1980s, remained comparatively stable during 1990s, and then declined further through the early 2000s. Interestingly, this decline in smoking was greater among men compared to women therefore, there is less difference between men and women regarding prevalence of smoking. Several factors have been observed to be associated with these sex-difference associated smoking rates, which includes lower rates of smoking cessation as well as post smoking cessation relapse in women compared to men [4].

Although the rates of cigarette smoking has declined over the past 50 years in the United States [5], alternatives like electronic cigarette (e-cig) products have gained rapid popularity among all age groups and sexes. Recent data demonstrates an alarming, consistent growth in female smokers. Surprisingly, young, and even pregnant women, are using e-cigs at a greater extent these days, considering it as a safer alternative to tobacco smoke. However, e-cigs also contains nicotine as a main constituent as well as other, potentially harmful components which may affect the cerebrovascular and cardiovascular systems and lung [6].

Several studies suggest that men and women differ in their smoking behaviors. It has been observed that women smoke fewer cigarettes per day and have a tendency of using cigarettes with lower nicotine content. Women also do not inhale cigarettes as deeply as men [7]. Interestingly, women may smoke for different reasons than men, including mood and stress management [8]. However, it is vague whether these differences in smoking behaviors are due to high sensitivity of women to nicotine, or they find the sensations associated with smoking less rewarding, or social factors contributing to the difference. Additionally, some research also suggests that women may experience more stress and anxiety as a result of nicotine withdrawal compared to men [9]. Risk of death from smoking-related lung cancer, COPD, heart disease, and stroke continues to increase among women, approaching rates for men [10]. According to data collected from 2005 to 2009, each year about 201,000 women die due to smoking related factors whereas the number is 278,000 for men [4]. Some health hazards associated with smoking, including blood clots, heart attack, or stroke, have been reported to increase in women who use oral contraceptives [11].

Along with sex, age is another determinant of smoking and nicotine action. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), currently the greatest rates of e-cig and tobacco smoking are observed in person between 25–44 years and 45–64 years respectively whereas the lowest cigarette smoking is observed in 18–24 aged people [12]. About 9 of every 10 adults who smoke cigarettes daily first try smoking by age 18, and 99% first try smoking by age 26 which represents that tobacco use is initiated and established primarily during adolescence stage. It is speculated that if the rate of cigarette smoking among youth continues to increase at the current rate, 5.6 million of Americans below 18 years will die early from a smoking-related illness [13]. Alarmingly, the e-cig vaping rate among adolescent and youth has been increasing rapidly. About 1 out of 20 middle school students (4.7%) and 1 of every 5 high school students (19.6%) reported in 2020 that they used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days [13]. It is also interesting that many young people are now using multiple tobacco products which may increase the risk for developing nicotine dependence and might be more likely to continue using tobacco into adulthood [13].Several studies have demonstrated that age and sex are important determinants for evaluating nicotine action and toxicity. Physiological differences between male and female along with age differences may alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacological effects of nicotine. Unpublished data from our research group has also demonstrated sex- and age-difference effects of nicotine on blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, cognitive function, and locomotor activity. However, there is a lack of study related to differences in nicotine action in both pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics perspective considering both sexes and different ages. Considering the impact of nicotine on human health and the role of age and sex on nicotine action, the aim of this review article is to summarize and discuss the effect of these intrinsic factors on nicotine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. We believe this comprehensive review will help the readers to understand the importance of considering sex and age dependent action of nicotine for the development of biologically relevant therapies for treating cerebrovascular and neurological dysfunctions.

2. Epidemiological data on tobacco/e-cig users based on age and sex:

Although smokers are aware of the toxic effects of nicotine, the use of nicotine through tobacco and e-cig remains a substantial cause of preventable deaths [14]. When comparing e-cig use to tobacco smoke use, the nicotine consumption regarding both users is comparable [15]. Worldwide, 30% of all men and 7% of all women are tobacco smokers which makes it around 1 billion in total number [14]. Currently in the US, 15.3% of men and 12.7% of women are tobacco cigarette users [16]. Men are nearly twice as likely as women to be an e-cig user. In 2018, 4.3% of men and 2.3% of women were current e-cig users [17]. Although a larger number of men are smokers, women have a harder time quitting and are more vulnerable to dependencies. Overall smoking cessation is declining, but the decline of women smokers is less pronounced than that of men [18]. For users, nicotine is a risk factor for a variety of health issues including cancer, lung disease, stroke, heart disease, and vascular diseases. In addition, use can reduce fertility in both men and women and can harbor dangerous effects on the fetus [14]. Although pregnant women are aware of the harmful effects smoking can have on the fetus, e-cig use among pregnant women ranges from 0.6% to 15% [19]. CDC data shows that around 7.0% of women use e-cigs around the time of pregnancy and 1.4% of women use them during the last 3 months of pregnancy [20]. The amount of women who smoke tobacco cigarettes during pregnancy remains comparable, amounting to 7.2% during pregnancy [21]. Table 1 summarizes the rate of tobacco smoking and e-cig vaping between male and female.

Table 1:

Sex-difference in tobacco smoking and e-cig vaping rate

In 2019, around 50.6 million adults nationwide admitted to using tobacco products. Cigarette use among adults was around 14.0% and e-cig use was around 4.5% [12]. Current data shows that those nationwide, 8.0% of adults aged 18–24, 16.7% of adults aged 25–44, 17.0% of adults aged 45–64, and 8.2% of adults aged 65 and older are regular cigarette users [16]. E-Cig use is highest among those aged 18–24 amounting to 9.3% [12]. E-Cigs are commonly used in youth, as 3.6 million youth used e-cig products in the past 30 days [22]. Evidence shows that adolescents are vulnerable to nicotine dependency which can lead to other deficits later in life [23]. In addition, nicotine use among adolescents increases the likelihood to participate in risky behaviors such as sexual activity and violence [24]. In 2020, an estimated 1 in 5 (19.6%) high school students and 1 in 20 (4.7%) middle school students were e-cig users [25]. There has been a continual decline in cigarette use but a 10% increase in e-cig use among adolescents [25, 26]. Table 2 summarizes the rate of tobacco smoking and e-cig vaping among different age groups.

Table 2:

Age-difference in tobacco smoking and e-cig vaping rate

These data clearly indicate that how nicotine containing product usage (tobacco and e-cig) is immersing into different age groups and both sexes at distinct rates and requires serious consideration.

3. The neurovascular system:

The neurovascular unit (NVU) is a dynamic structure in which multicellular interaction of blood vessels and the brain is responsible for the integrity of the vascular and nervous systems in the body [27]. Neurons, astrocytes, pericytes, microglia, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix are all integral components of the NVU. Working together, the neurovascular unit maintains a selective blood-brain barrier (BBB), cerebral homeostasis, and cerebral blood flow. The BBB acts as an interface between the brain and periphery, regulating major ions, solutes, and nutrients across the brain and blood and prevents movement of harmful molecules to the brain [28]. The homeostatic function of the BBB occurs at the brain microvascular endothelium level, where brain endothelial cells are the primary anatomical unit that maintains selective permeability. However, the brain endothelial cells do not form the intrinsic barrier solely by themselves but from interaction with other components of the unit [29, 30]. The mechanism of linkage of neurons and the cerebral vessel is often regarded as neurovascular coupling. This crucial association occurs with the release of glutamate through the activation of neurons. Glutamate further activates astrocytes, pericytes, and other vasoactive mediators, regulating cerebral blood flow [31]. Astrocytes, major glial cells of the NVU, have foot processes across the blood-brain barrier and form a complex network surrounding the capillaries [32, 33]. The close association between these cells further helps in the induction of the barrier properties. Pericytes are discontinuously distributed across the cerebral capillary, and the endothelial cells are enclosed by and contribute to the formation of the extracellular matrix, also called the basal lamina. Pericytes are essential in angiogenesis and vesicular transport of essential molecules across the BBB [34]. Moreover, the vascular pericytic coverage correlates with the inter-endothelial junction tightness across the barrier. The microglia serve as immunocompetent cells that, together with astrocytes and extracellular matrix, release vasoactive agents and cytokines, which further establish tight junction formation and barrier permeability [34].

The molecular characteristics of the brain microvascular endothelium that ensures ‘barrier’ like function is due to endothelial cells connected by adherens junction (AJs) and then sealed up by tight junction proteins (TJs) [35]. AJs constitute cadherin proteins that bridge the intercellular cleft, and these proteins are scaffolded with the cell cytoplasm by alpha, beta, and gamma catenin. Cadherins are essential for the formation of AJs and maintenance of the structure and integrity of the BBB. The TJs constitute another group of proteins, claudins and occludin, that bridge junctional adhesion molecules and the intercellular cleft. The claudins and occludin are linked further by regulatory scaffolding proteins ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, and cingulin to intracellular actin and the cytoskeleton [31]. The TJs are responsible for the strict restriction of ions and solutes through paracellular diffusional pathways, resulting in high electrical trans endothelial resistance of around 1800 Ω cm2 across the BBB [36]. The components of BBB and associated function clearly indicate the importance of a healthy neurovascular unit to avoid cerebrovascular dysfunction [37].

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor:

As a major pharmacologically active chemical in tobacco smoke, nicotine exerts its biological effects and action through binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAchRs) [38]. Neuronal nAchRs are pentameric transmembrane cation channels which belong to the superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels that include the GABA, 5-HT and glycine receptors and consist of α2–10 and β2–4 subunits. Endogenous (acetylcholine) or exogenous (nicotine) agonists bind to nAChR and open an intrinsic ion channel in the receptor, resulting in the flow of cations (Na+, Ca2+, and K+) through the cell membrane and induce a wide variety of biological responses [38]. The composition and neuroanatomical localization of the receptor regulate different pharmacologic and biologic actions. nAChRs are expressed in brain regions which regulate a variety of behaviors. β2 nAChRs and α7 nAChRs are the most common subtypes in the CNS which are expressed in the amygdala, dorsal striatum, and thalamus but with neuroanatomical overlap in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), cortex, hippocampus, and basal ganglia [39–41]. These brain regions control sensory transmission, learning and memory function, emotion, and reward. The α6β2 nAChRs are selectively expressed in catecholaminergic nuclei and enriched in the mesolimbic DA system, which is believed to be associated with addiction. The α3β4 nAChRs have reasonable expression in the CNS but are highly expressed in the medial habenula (mHb) to interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) pathway with a small subset of these receptors containing the α5 (i.e. α3α5β4) [42–44]. The mHb-IPN pathway controls the mesolimbic system and is highly involved in smoking phenotype. Also, the α3 and β4 nAChRs form nAChRs in the ganglion, raising attention to possible side effects associated with peripheral nervous system that could result from drug targeting of α3β4 nAChRs. A small number of α3β2 nAChRs in the habenula and IPN may be considered important for smoking phenotype, however there are currently limited tools to assess this [45]. These studies demonstrate the role of nicotinic receptors in different biological responses which could be altered by nicotine exposure.

4. Sex-difference and age-dependent effect on BBB integrity and disruption:

4.1. Role of sex on BBB disruption:

The BBB disruption can either be a cause or an effect of neurodegeneration, which is yet to be elucidated. However, based on disease prevalence between male and female patients, sex possibly plays a crucial role in the BBB disruption associated with several diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and motor neuron disease, which demonstrate clear sexual dimorphisms [46].

Several studies have been conducted using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines from both male and female subjects induced to brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs). These experiments suggest that iPSC-derived BMECs from pre-menopausal women have reduced permeability, and increased barrier strength, compared to iPSC-derived BMECs from men. Lippmann et al. reported that DF19–9–11T cell line from male demonstrated a significantly lower trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) value (777 ± 112) relative to the female IMR90–4 cell line (1450 ± 140). However, male DF19–9–11T cells showed higher platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1 or CD31) expression compared to the female IMR90–4 cells (75% vs 68%) [47]. Expression and association of PECAM-1 in BMEC tight junction integrity [48] indicates an increase in other tight junction proteins possibly resulting in higher TEER values in the female IMR90–4 BMEC. Sex differences in BBB permeability are also evident in the SAMP8 mouse model of accelerated aging [49]. Increased mRNA expression of tight junction proteins (claudin-1, claudin-5, claudin-12, occludin, ZO-1), junction adhesion molecule A (JAMA), major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been observed in female mice compared to male [49]. This study indicates sex-different expression of tight junction proteins which could affect brain endothelial cell interaction and transient changes in BBB permeability. Sex dependent BBB characteristics should be further studied in future capitalizing on different in vitro and in vivo models [46] to more precisely determine the role of sex as a biological determinant of neurovascular function in brain diseases.

Sex differences in shear stress responses may also impact susceptibility of neurodegenerative disease. Cerebral vasodilation is important for glucose supply to metabolically active brain areas by increasing local blood flow [50]. A human brachial artery study suggested that the endothelium of pre-menopausal women may have more sensitivity to shear stress, leading to increased vasodilation compared to similar aged men and post-menopausal women [51]. Gracilis muscle arterioles isolated from female rats showed increased flow-mediated dilation compared to male counterparts, which decreased wall shear stress and shear stress-induced endothelial damage [52]. Decreased arterial [53] and capillary pressure [54] was also observed in pre-menopausal women compared to men. Although these studies did not consider brain, it has been suggested that women may have increased vasodilation in response to shear stress in the cerebral vasculature as well [46].

Sex difference may also impact vasodilation through endothelial-derived hyperpolarization (EDH). In EDH, stimulation of G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) increases intracellular calcium and hyperpolarizes the cell membrane. This hyperpolarization is believed to be transmitted through gap junctions to smooth muscle cells, resulting in dilation of the blood vessels, thereby increase cerebral vascular perfusion. A recent study related to EDH aging has reported reduced GPCR function in male mice compared to age-matched female mice, leading to a decreased EDH response [55]. On the contrary, increased EDH has been shown in female rat following ovariectomy which was reversed with estrogen supplementation, indicating that estrogen may decrease the EDH response. Interestingly, the EDH response is attenuated by NO [56], which increases with estrogen [57]. It is apparent that more studies are needed to confirm direct relationships between EDH and female sex hormones [46].

These abovementioned studies on sex-different BBB disruption clearly indicate the importance of inclusion of both sexes in preclinical and clinical studies to design proper treatment strategies associated for BBB-disrupted cerebrovascular diseases.

4.2. Role of age on BBB disruption:

The age-associated decline of the neurological and cognitive functions becomes a serious challenge for developed countries which have large number of aged populations. Multiple investigations have focused on morphologic and biochemical differences in the aging brain. There is no specific age range to define physiological aging, however it can be defined as a deterioration of physiological processes without cognitive dysfunction and dementia concerning brain and BBB [58]. Several studies have reported that aging has significant impact on essential components of the BBB and is associated with impairment and disruption of the BBB contributing to several neurodegenerative disorders. Table 3 summarizes the effects of aging on BBB components.

Table 3:

Effect of physiological aging on components of blood-brain barrier (BBB)

| Component of BBB | Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial cells (ECs) | Capillary wall thickness: increased in human and decreased in rats and monkeys | [59–62] |

| Number of ECs: decreased in human | ||

| Number of mitochondria: decreased in rodents and human | ||

| Tight junctions (TJs) | Expression: decreased in mice | [63, 64] |

| Basal lamina | Thickness: increased in human | [65, 66] |

| Concentration of laminin: decreased in human | ||

| Concentration of argin and collagen IV: increased in human | ||

| Astrocytes | Proliferation: increased in human | [67–70] |

| GFAP expression: increased in human and rodents | ||

| Pericytes | Number: loss of pericytes in human | [60, 61, 71, 72] |

| Ultrastructural changes: vesicular and lipofuscin-like inclusions, increased size of mitochondria, foamy transformation in rodents | ||

| Neurons | Neurogenesis: impaired in mouse | [73–76] |

| Apoptosis: increased in rats | ||

| Synaptic plasticity: deteriorated in rats | ||

| Neuronal damage in rodents | ||

| Deficit in long term potentiation in rats | ||

| Microglia | Changes to amoeboid morphology in human | [77, 78] |

| Production of neurotoxic mediators such as nitric oxide and peroxide and proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α), proteases and complement components in rodent and human model. |

Neurodegeneration is considered as an essential component of age-related pathology. It can be defined as progressive loss of neuronal structure and function resulting in neuronal cell death. Most of the neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and pharmaco-resistant epilepsy, have been found to begin in mid-life. These diseases can be characterized by motor and/or cognitive dysfunction that progressively deteriorates with age and may reduce life expectancy [58]. Thus, it is evident that age can play a significant role on BBB disruption and associated cerebrovascular dysfunction.

5. Effect of nicotine and TS on cerebrovascular disorders and critical role of sex and age:

Nicotine is the key constituent of tobacco smoke (TS) and also present in e-cig products. TS is one of the leading causes of preventable death and is accountable for over 480,000 deaths each year in the US [79]. Tobacco smoke is a varied mixture of more than 4700 toxic chemicals that are carcinogenic and mutagenic. Nicotine, carbon monoxide, and oxidants such as free radicals and nitrogen oxides are a few of the many constituents of TS that are considered both cardiotoxic and neurotoxic [80]. TS has been associated with worsening ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury, and other neurological diseases such as AD, MS, and Neuro-AIDS [81–85]. Preclinical studies attribute TS to vascular endothelial dysfunction in a causative and dose-dependent manner related to acute or chronic nicotine exposure, ROS content of TS, and oxidative stress-driven inflammation [86–88]. On the other hand, e-cig vaping contains significantly less harmful constituents than TS, but a study has been linked to similar oxidative stress-driven inflammatory potential [89]. Additionally, side-by-side experiments involving e-cig and TS use showed a similar risk of blood coagulation [90]. Nevertheless, the negative effect of nicotine containing e-cigs on various neurological disease states has not been explored as much compared to TS.

5.1. Ischemic stroke (IS):

Ischemic stroke is characterized by a transient or permanent block of blood flow to the brain due to occlusion of a major cerebral artery by a clot or an embolus [91]. It remains the fifth leading cause of death in the US, and TS is a well-known risk factor [92]. In a study using an experimental stroke model, nicotine exacerbated ischemic reperfusion injury by increasing brain edema formation [93]. Additionally, in both in vitro and in vivo stroke settings, researchers found that there was a decrease in Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter activity at the BBB level after nicotine or tobacco smoke exposure [94–96]. Likewise, apart from single nicotine exposure, studies have shown e-cig vaping causes cellular oxidative stress by nuclear translocation and increased expression of Nrf2, a major regulator of anti-oxidative defense mechanism, loss of BBB integrity, and cellular inflammation [97–99]. Furthermore, these studies demonstrated a decreased level of thrombomodulin, an anticoagulant factor, and an increased level of TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, in animals exposed to TS and e-cig vapors. Lastly, similar stroke outcome assessed by neurological evaluations was observed in both e-cig and TS exposed animals. Thus, e-cig vaping could be as dangerous as TS concerning negative effects on the BBB and cerebrovascular system and could promote post-ischemic brain injury.

Sex and age have been identified as complex and interactive determinants on ischemic stroke risk and pathophysiology. Preclinical studies of sex differences show that female animals are less prone to ischemic stroke than male animals [100]. Interestingly, estrogens have shown to be highly neuroprotective in the context of ischemic stroke because of their anti-atherogenic effect in the vasculature and subsequent regulation of adipogenesis [101]. Moreover, in ovariectomized animals, the advantage of the female group being less prone seems to disappear, thus supporting the role of estrogen in ameliorating ischemic stroke in the female population [102, 103]. However, age reverses this in female mice, as shown by a study that found that middle-aged (16 months) female mice had larger brain infarct and poor recovery compared to male animals [104]. It is believed that this factor is attributable to the loss of estrogen in the female population at this age. Furthermore, exogenous 17β-estradiol has been shown to reverse the worsened outcome in female animals [105]. Studies show that male animals have higher ischemia-induced microglial activation in neonatal and young adult life stages than female animals [106]. Similarly, in vitro studies show that primary brain endothelial cells derived from male mice are more sensitive to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) than female cells [107]. Astrocytes, vital for BBB integrity, also follow a similar trend to other cells to be more sensitive to ischemia in male animals. A study showed that female astrocytes are resistant to OGD-induced ischemic damage, and that too depends on estrogens [108].

Age is one of the significant nonmodifiable risk factors for ischemic stroke. Elderly stroke patients have higher morbidity and mortality rate and poorer functional recovery compared to young patients [109]. Interestingly, it has been reported that sex-different effects in ischemic stroke epidemiology depend on patient age as the influence of sex on stroke risk and outcome changes across the lifespan [109]. In childhood and early stage of adulthood, men experience higher IS incidence and poorer functional outcomes compared to women [110, 111] while in middle age, IS rates begin to increase in females, associated with the onset of menopause and loss of female sex hormones [112]. After middle age, continuous increases in stroke rates have been observed in women, while some of the studies reported on the higher stroke incidence in elderly women (age >85 years) compared to elderly men [110, 111]. Moreover, adolescents experience acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with an annual incidence ranging from 0.54 to 2.4 per 100,000 which results in devastating consequences including psychomotor development, disrupted quality of life, future work inability, and familial and financial costs. Several factors have been identified which might play an important role in stroke genesis in adolescence for instance growth spurts inducing the rapid and important anatomic evolution of heart and neck vessels, hormonal changes, and exposure to lifestyle or environmental factors such as use of tobacco, drugs, or oral contraceptives [113]. Hence, the occurrence of stroke in adolescents’ and young adults has a disproportionately huge physical, social, and economic impact by leaving stroke victims disabled before their most productive years [114].

All these abovementioned studies indicate that age and sex influence ischemic stroke risk and outcome, but in a complex manner and, in future, it is important to explore sex and age different effects on nicotine induced IS for developing effective and personalized therapeutics

5.2. Traumatic brain injury (TBI):

Traumatic brain injury or TBI is one of the most common causes of death and disability related to cerebrovascular and neurologic complications [115]. Each year, around 69 million people suffer from TBI around the world and the majority of TBIs are mild (81%) to moderate (11%) [116]. Chronic smoking is a premorbid risk factor that will impact the severity of TBI and retard post-traumatic recovery. Both preclinical and clinical studies have shown that TBI with premorbid TS exposure results in exacerbated post-traumatic neuroinflammation and cerebrovascular conditions compared to non-smokers [117, 118]. The likely mechanism includes the generation of ROS-driven oxidative stress leading to membrane damage and tissue necrosis. Similarly, findings from another preclinical TBI study showed that animals exposed to TS had worse post-traumatic motor activity than TBI alone [83]. Downregulation of Nrf2 in TS pre-exposed TBI animals was also observed in same study. Further study needs to be conducted to assess the effect of e-cig or vaping on TBI as no study is available as of today.

Interestingly, sex and age have been identified as important determinants to measure TBI outcome. Several studies have reported less post-TBI delayed injury as well as better functional outcomes in younger females compared to older females which is probably due to the neuroprotective effects of sex hormones in pre-menopausal women [119, 120]. Higher level of interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF α) and chemokine ligand 2 have been found in female mice compared to male mice. However, anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10 (IL-10) was found to be higher in male, not in female mice [121]. Although the neuroprotective effects of sex hormones have been observed in experimental animal models, several clinical trial studies utilizing female sex hormones showed contradictory results [122, 123]. Women have been reported to be more vulnerable to post-TBI brain damage and mortality rate compared to men [124]. Women showed 1.28 times higher post-TBI fatality rates and 1.57 times more likely to suffer from acute or/and chronic post-traumatic symptoms like severe disability relative to men [125]. Moreover, microglia and astrocytes induced inflammatory responses after TBI have been observed higher in women than men [126]. A large randomized controlled trial on TBI patients around world suggested that women experienced deteriorated short and long term post-TBI outcomes [127]. In addition, better post-TBI outcomes have been observed in postmenopausal women compared to age-matched men, whereas pre-menopausal women have shown the same outcomes as age-matched men [128]. Thus, clinical and preclinical studies on sex and age effects on post-TBI vulnerability are still conflicting due to the heterogeneous mode of injury and population.

In addition, age should also be considered in measuring the differences related to TBI pathophysiology, post-TBI outcomes and recovery. Studies have shown that the response of the developing brain to TBI differs from the response of the mature, adult brain. There are critical developmental trajectories in the young brain, whereby injury can lead to long term functional abnormalities [129]. Children have shown better recovery rates compared to older patients due to their greater degree of neuroplasticity [130]. Post-TBI mortality rate has been found higher (24%) in elderly patients whereas it is only 12.8% in other age groups. Although elderly patients suffer comparatively less severe head injuries compared to non-elderly patients, however they have shown slower recovery rates and tend to experience more distress [131]. Moreover, TBI among adolescents have been identified as a significant public health concern globally in the past 15 years. A recent study has demonstrated that 15 to 19 years old adolescents have some of the highest emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths related to TBIs compared to other age groups. About 20% and 22% of adolescents sustain a TBI in their lifetime in US and Canada respectively, and as many as 5.5% have multiple injuries [132]. Age-dependent effect has been also observed in post-TBI rehabilitation therapy. Although age does not affect the degree of functional improvement obtained during inpatient rehabilitation after TBI [133], however several studies have shown that older TBI patients experience poorer rehabilitation outcomes than younger patients [134, 135] suggesting the significance of age consideration on post-TBI rehabilitation strategy.

As TBI has been increasing rapidly among women [136]and the post-TBI outcome differ between men and women, it has become more important to understand the complex interplay between sex and age in the pathophysiology of post-TBI for finding an effective therapy for both sexes.

5.3. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and multiple sclerosis (MS):

TS is associated with an increased risk for the prevalence of various types of dementia, specifically AD and vascular dementia [81]. AD is pathologically characterized by selective loss of nAchR and elevated deposition of amyloid-β. Studies have suggested that smoking enhances amyloid-β deposition and has more severe neuropathological variation than non-smokers [137]. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is one of the variations that might be attributable to smoking enhanced amyloid-β deposition. A research study has reported increased amyloid-β buildup contributes to reduced tight junction proteins and increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), which eventually leads to BBB dysfunction [81]. Amyloid-β is often co-localized to the α7 subunit of nAchR. On its elevation, it binds to the subunit with high affinity and inhibits neuroprotective activity leading to synaptic degeneration [138].

Clinical and preclinical studies have shown that females have an increased risk of AD compared to males [139–141]. This might be attributable to age-related hormonal imbalances, the risk from other diseases such as diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular diseases, and sex differences in brain anatomy and brain glucose utilization [142, 143]. The female hormone estrogen has a sharp decline after menopause in women while testosterone levels slowly decline in males in advanced age, which may contribute to the sex dependent pathology observed in AD. In addition, estrogens have been shown to increase neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus and CA1 of the hippocampus that contributes to learning and memory [144]. Studies have also reported that estrogens reduce Aβ levels by promoting their clearance by stimulating microglial phagocytosis and degradation [145, 146]. Similarly, depletion of progesterone and estradiol resulted in increased levels of Aβ in transgenic mouse models of AD [147]. These studies suggest the potential role of sex hormone and possible sex-different effects on Alzheimer’s disease.

Aging is the most crucial known risk factor for developing AD. Studies have shown that the number of people with AD doubles about every 5 years beyond age 65 and around one-third of all people aged 85 and above may have AD. Alzheimer’s disease can be divided into two categories: early onset and late onset. Early-onset AD occurs between 30 to mid-60 years and represents less than 10 percent of all people with AD whereas late onset represents symptoms which occur at mid-60. Several age-related changes in the brain have been identified which may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease including but not limited to atrophy, inflammation, vascular damage, ROS production and disruption in energy production in cells [148].

Likewise, multiple sclerosis or MS, an autoimmune neurodegenerative disorder, has a deteriorative prognosis in the smoking population [84]. Increased serum MMP-9 concentration is considered a hallmark in MS. Interestingly, TS has been reported to be associated with an increased level of serum MMP-9. MMP-9 degrades the extracellular matrix and helps migrate autoreactive immune cells into the CNS through the BBB [149].

Several studies suggested that sex-difference affects the susceptibility and progression of multiple sclerosis. Higher prevalence and better prognosis have been observed in women compared to men

This sex dimorphism may be explained by the potential role of sex hormones and sex chromosome on immune system, brain damage and repair mechanisms [150, 151]. Preclinical and clinical studies as well as MRI evidence confirms a pathogenetic link between sex hormones and MS, suggesting the sex-different effects of hormones in multiple sclerosis pathophysiology and therapy [150]. Hormonal fluctuations in menstrual cycles, pregnancy, exogenous sex steroids intake have been found to be associated with MS exacerbations. Studies have reported the association between pregnancy, specifically the late stage of pregnancy and decreased clinical symptoms or relapse rate in MS [152–155]. This is observed mainly in the third trimester when estrogen and progesterone levers are increased (up to 20 times than normal) [156]. Based on the potential role of sex hormones in MS, it has been suggested that steroid supplementation may show beneficial impact on MS due to its immunoregulatory, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties [151] although further investigations need to be conducted for proper treatment and management.

In addition, age is considered as a major determinant of onset of MS progression. Accumulating evidence suggests that MS prognosis depends on age at some extent regardless of initial, exacerbating or remitting or progressive disease course [157–160]. Many age-dependent changes have been identified to affect the brain which can collectively affect neuronal viability as well as MS vulnerability. These changes include, but not limited to, increased iron accumulation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial injury, decreased trophic support from the peri-plaque environment, reduced remyelination, and elevated production of inflammatory molecules such as pro-inflammatory cytokines [161–165]. Interestingly pediatric and adolescent MS have been reported in several studies from all over the world. MS onset during childhood accounts for 5% of total MS patients in the US [166]. A relapsing-remitting MS occurs in more than 97% of MS patients with onset before the age of 18 years which is an important factor to be considered [167].

5.4. Neuro-AIDS:

TS exacerbates neuro-AIDS, a group of neurological disorders resulting from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the central nervous system, in which cytokines and toxins are released by the infected brain endothelial cells and give rise to BBB breakdown and neurological pathogenesis. Studies have reported that oxidative stress induced by TS results in disease progression [85]. In addition, nicotine augments viral replication by activating cellular gene progression and inducing oxidative stress in macrophages by CYP2A6 metabolism [168, 169]. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to explore the exact mechanism through which nicotine or other components of TS mediate neuro-AIDS progression.

Clinical and preclinical studies reporting the effect of sex as a biological determinant in magnitude and pattern of neuro-AIDS are inconsistent [170]. Early clinical reports observed no sex differences in the progression of neurocognitive deficits [171]. However, recent clinical studies have reported that HIV-1 seropositive women had impaired learning and memory, verbal fluency, and information processing capability than HIV-1 seropositive men [172]. Additionally, female animals with HIV-1 transgene showed worse locomotor activity, objection recognition memory, and temporal processing compared to male animals [173, 174]. In contrast, a study reported that female transgenic animals showed decreased anxiety-like behavior and increased forelimb grip test compared to male animals [175].

In elderly healthy people, immune activation and inflammation play a vital role in the gradual decrease of the immune system’s functiona lity [176]. However, aging with HIV infection has been shown to exacerbate immune activation and inflammation pathways, leading to neurocognitive impairments [177]. Microglia, the main resident immune cells, switch to an activated state after the viral invasion [178]. Furthermore, they interact with the infiltrating immune cells such as macrophages and T and B lymphocytes in the CNS and trigger neuroinflammation. Other possible consequences include poor adherence to medication in the elderly and expression of apolipoprotein -E4 [179, 180]. Also, excess hyperphosphorylated tau, alpha-synuclein, and amyloid have been reported in relatively aged HIV-positive patients [181, 182]. Moreover, children can acquire HIV-1 through mother during the antenatal, perinatal, or breastfeeding periods and develop neuro-AIDS. With the survival of children in adolescence and adulthood, there is an increasing concern regarding neurocognitive disorders, psychosocial development, and psychiatric disorder. Perinatally HIV infected adolescents have been reported to face difficulties in decision making and risk taking [183]. Further studies are warranted to understand the exact mechanisms underlying age and sex differences in neuro-AIDS.

These studies clearly explain the effect of nicotine on cerebrovascular dysfunction as well as neurodegenerative disorders and describe the role of biological determinants (sex and age) on these diseases. Extensive studies need to be conducted to evaluate the sex and age-dependent effects on nicotine induced cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disorders for designing better treatment strategy in these populations.

6. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nicotine:

6.1. Nicotine pharmacokinetics:

Pharmacokinetics refer to the fate of a drug or compound after entering the body involving absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of that drug or compound. Pharmacokinetics of nicotine depends on physicochemical properties, route of administration as well as the physiological system. Different routes of administration are available for nicotine self-administration including inhalation, ingestion, and intra-nasal, buccal, and transdermal absorption. The most common route of self-administration is inhalation in a form of tobacco products, for instance, cigarette, electronic cigarette, hookah, cigars. Moreover chewing, snuff, and dissolvable lozenges containing nicotine are available [184].

Absorption:

Nicotine is rapidly absorbed into mucosa, respiratory tissues and skin because of its water and lipid solubility property. Oral nicotine products are buffered to alkaline pH that helps absorption through the mucous membrane lining the mouth [185]. As stomach has very low pH (highly acidic), less nicotine is absorbed in stomach [186] but rapidly absorbed in the small intestine and undergoes first pass metabolism which results in decreased bioavailability [187]. Nicotine bioavailability also depends on route of administration. Bioavailability of nicotine is around 80–90% via smoking while 51–56% through nicotine inhaler [185]. Alkalinity or acidity of smoke from cigarette can affect the rate and extent of nicotine absorption probably due to presence of non-protonated, free-base nicotine in tobacco smoke which promotes better nicotine transfer into the respiratory epithelium [188]. In addition, nicotine in e-cig liquid can exist as free base or protonated (salt form). Protonated or salt form of nicotine makes the inhalation less aversive compared to free base nicotine ( e.g. Juul) yielding high nicotine concentration and increased bioavailability in a small puff volume [189]

Distribution:

After reaching to the small airways and alveoli of the lung, nicotine transports readily into arterial and venous circulation. Nicotine reaches the arterial circulation very rapidly, within 7–24 s after the first puff inhalation [190] and maximal venous blood plasma concentration ranges from 15 to 30 ng/ml within 5 minutes [186]. It has been reported that within 5–7 s of the start of an initial puff of cigarette smoke, nicotine reaches the brain and the maximal nicotine concentration in brain was found within 3–5 minutes [191, 192]. Nicotine distributes throughout the body with a steady-state distribution volume ranging between 2.2 and 3.3 L/kg [186, 193]. Nicotine concentrates in different parts of the body, mostly in the lung, liver, kidney, spleen, and brain. It can freely cross the placental barrier and can transfer into breast milk and cervical fluid as well [194]. The distribution half-life of nicotine is approximately 9 min [195].

Metabolism:

Nicotine metabolism primarily occurs in liver, but lung and kidney are also involved in biotransformation of nicotine [186]. Around 80% of nicotine is metabolized into major metabolite cotinine involving two steps process. In the first step, nicotine is hydrolyzed to 5-hydroxycotinine by CYP450 2A6 enzyme resulting in nicotine-iminium ion. In the second step, aldehyde oxidase enzyme produces cotinine [193, 194]. Around 4–7% of nicotine is metabolized to nicotine N′-oxide by flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 enzyme [186] and roughly 3–5% of nicotine is transformed to nicotine glucuronide via glucuronidation reaction catalyzed by uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme [193]. In addition, a small fraction of nicotine (0.4–0.8%) is metabolized into nornicotine probably by CYP450 enzyme [186]. Nicotine metabolism could be impacted by several factors including but not limited to sex, age, genetic polymorphism, race, ethnicity, diet, certain health conditions and use of certain medications [186]. Age and sex dependent effect on nicotine metabolism has been explained extensively in the later part of this paper.

Excretion:

The elimination half-life of nicotine ranges from 100 to 150 minutes. Around 15% of nicotine is excreted in the urine as unchanged involving glomerular filtration and tubular secretion. The rate of renal clearance is about 35–90 ml/min. Moreover, a small amount of nicotine is excreted through feces and sweat. Metabolites of nicotine including nornicotine, cotinine, nicotine-n-oxide, nicotine glucuronide are also excreted in urine. Hukkanen et al reported that approximately 10–15% of nicotine and its metabolites are excreted in urine as 4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butanoic acid and 4-hydroxy-4-(3-pyridyl)butanoic acid [186].

6.2. Nicotine pharmacodynamics:

Nicotine is structurally similar to endogenous neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Ach) and binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAchRs).The nAchRs containing α4 and β2 subunits are the most abundant and particularly the β2 containing nAchR mediates reinforcing effects of nicotine [196, 197]. The β2 subunit is crucial for nicotine-mediated DA release and behavioral responses including nicotine self-administration, conditioned reinforcement, conditioned place preference (CPP), and locomotor activity [197]. Consistent upregulation of β2 nAchRs in brain by nicotine has been observed in some seminal preclinical and postmortem human studies [198]. Higher β2 nAchR in the cortex and striatum has been found in smokers when they imaged at 7–9 days of smoking abstinence compared to non-smokers [199, 200].

Nicotine-induced actions at nAChRs in the brain can be either excitatory or inhibitory depending on the site of action. The neurotransmitters dopamine (DA), glutamate, and GABA mediate nicotine’s effects through a complex network of projections between brain regions key in reward-seeking behavior, learning and memory, emotion, and daily function [184]. Long term exposure to nicotine from tobacco smoke use is associated with physiological dependence and tolerance due to receptor desensitization [201]. In receptor desensitization, agonist-dependent confirmational change from active to inactive site happens and the receptor loses its sensitivity to agonist. It has been reported that day-long continued nicotine exposure at low concentration results in strong, deep desensitization of primarily the β2-type nAchRs [202]. On contrary, the α7 nAChRs do not get desensitized with the low concentrations of plasma nicotine in smokers due to their low affinity for nicotine [203]. This chronic desensitization results in nAchRs dysregulation which plays a pivotal role in development and maintenance of nicotine addiction [202]. Upregulation of nAChR number has been observed in the brain autopsy reports of smokers [204].

Moreover, abrupt removal of agonist stimulation at nAChRs leads to reduced level of neurotransmitter release [194] and alteredhomeostasis. Smoking cessation in long-term tobacco users often demonstrates mild but uncomfortable withdrawal syndrome including but not limited to restlessness, irritability, insomnia, anxiety, depression, loss of appetite and cognitive dysfunction at its worst within the first week of abstinence, however it eventually disappears over a period of weeks [184].

The mesolimbic DA system, including the DA neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a target for addictive drugs, projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) of the ventral striatum [205–208]. A single dose of nicotine induces synaptic plasticity that increases the activity of VTA DA neurons [205, 207, 209, 210]. Hence, dopamine (DA) and dopaminergic pathways play a crucial role in reinforcing effects of nicotine. It has been reported that β2-nAChRs on DA neurons gets activated by acute nicotine administration which results in DA release within the mesolimbic DA system [211]. The extent of ventral striatal DA release is associated with the pleasurable response to nicotine in humans [212]. On the other hand, selective lesions of DA projections to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) or nAChR antagonists administration into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) blocks nicotine-induced behavior [211] suggesting the pivotal role of DA system on nicotine action. Moreover, DA D2/D3 receptor availability as well as increased DA released has been measured in in-vivo using PET imaging [213].

7. Factors impacting nicotine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics:

Several factors have been identified affecting nicotine pharmacokinetics, specifically metabolism and nicotine pharmacodynamics. Physiological factors (diet, meal, sex, age), use of medications (inducer, inhibitor), smoking behavior, race and ethnic difference, genetic polymorphism, and certain medical condition impact metabolism and clearance of nicotine [185]. Among these abovementioned factors, sex and age play a crucial role in nicotine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

8. Role of sex on nicotine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics:

8.1. Role of sex on nicotine pharmacokinetics:

Sex differences have been observed in several studies related to body weight, plasma volume, plasma protein levels, gastric emptying time, cytochrome P450 enzyme activity, drug transporter, renal and excretion activity which ultimately affect nicotine pharmacokinetics [214]. Nicotine brain levels were found to rise faster in female CD rats compared to males following nicotine injection, prominently in the cortex suggesting that female rats are more sensitive to nicotine than male rats [215, 216]. Urinary nicotine metabolite profile also revealed sex differences between male and female rats [216, 217]. Lower plasma cotinine levels were observed in female rats compared to males as higher urinary recoveries of nicotine and higher urinary output of nicotine metabolites were observed in females and males respectively, suggesting a decreased nicotine metabolism rate and larger volume of distribution in females. Moreover, faster nicotine metabolism was reported in male rats following an acute intravenous (IV) injection [218]. However, chronic nicotine administration showed contradictory results in some studies. Chronic nicotine administration by subcutaneous (SC) injection for 15 days (0.6 mg/kg) demonstrated the same level of cotinine in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats although lower levels of nicotine were measured in females compared to males, indicating the shorter half-life of nicotine in females [219]. Future controlled studies are needed to determine the impact of sex on nicotine brain bioavailability and PK to understand the apparent sex differences observed in nicotine addiction.

Role of hormones:

Nicotine is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes, predominantly CYP 2A6. The higher the activity of CYP2A6, the faster nicotine will be metabolized, which is related to high nicotine dependance [220]. Activities of CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 have been found higher in female compared to male, demonstrating the potential role of female sex hormones on nicotine metabolism. This hypothesis has been tested to determine the effects of pregnancy, contraceptives, and menopause on nicotine metabolism

Pregnancy:

Accelerated metabolism of nicotine and cotinine was observed in pregnant smokers [221]. Following infusion of deuterium-labeled nicotine and cotinine in 10 healthy pregnant smokers, both renal and non-renal clearance of nicotine and cotinine were measured from blood and urine samples. Increased clearance of nicotine and cotinine (60% and 140%) and shorter half-life of cotinine were found during the second half of pregnancy compared to that observed postpartum. These data suggest that increased smoking might be expected during pregnancy to compensate for elevated nicotine elimination. However, no change was observed regarding nicotine intake between pregnancy and postpartum stage suggesting either that smoking during pregnancy is not influenced by nicotine elimination or that other factors also contribute to smoking rates during pregnancy [221]. Another study, which included pregnant smokers (who could not quit heavy smoking during/after the first trimester), demonstrated a pharmacokinetic predisposition to a higher rate of nicotine metabolism [222]. Future studies are needed to determine the influence of pregnancy on nicotine metabolism which could influence preferences for certain tobacco products and usage patterns.

Use of oral contraceptives:

Although prevalence of oral contraceptive use is high in premenopausal women, less studies exist testing the relation between oral contraceptives and nicotine. Some studies have reported on oral contraceptive mediated nicotine metabolism, indicating the potential role of estrogen levels on faster metabolism of nicotine [223–225]. The role of oral contraceptives on nicotine metabolism has been observed in a study involving two hundred and seventy-eight volunteers. Nicotine and cotinine metabolism were faster in women taking oral contraceptives compared to the control group who did not take oral contraceptives. Also, among oral contraceptive taking volunteers, accelerated rates of nicotine metabolism were observed in the group who took combined, or only estrogen oral contraceptive compared to only progesterone oral contraceptive users [225]. It has been suggested that higher rates of nicotine metabolism could be associated with intense smoking [225, 226], more rewarding effect [227], greater withdrawal symptoms [228] as well as worse smoking cessation outcomes [229, 230]. These outcomes propose that use of oral contraceptives may increase nicotine metabolism which may result in increased dependency on nicotine and, therefore, have more difficulties achieving abstinence.

Menstrual Cycle:

Endogenous female hormones can regulate nicotine metabolism suggesting the role of menopausal stage on nicotine metabolism. Benowitz et al conducted a study on premenopausal (n= 145), menopausal (n=25) and postmenopausal (n=13) women compared to men. Premenopausal women showed faster metabolism of nicotine compared to men however, men did not show a significant difference compared to menopausal and post-menopausal women. Also, nicotine clearance in premenopausal women did not significantly differ from those in menopausal or postmenopausal women. However, cotinine clearance was found higher in premenopausal women compared to menopausal women [225]. Although this study did not consider the phase of menstrual cycle, another study reported that nicotine or cotinine clearance does not get affected by phase of the menstrual cycle [231]. Moreover, menstrual cycle phase did not affect the hemodynamic response to nicotine, activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis or catecholamine secretion response following IV nicotine infusion. In the luteal phase of menstrual cycle, norepinephrine levels were found to be higher however, this did not seem to influence neuroendocrine response to IV nicotine. Hence it has been suggested that different physiological levels of ovarian hormones across the phases of menstrual cycle are not enough to explain the notable increase in women smoking during luteal phase. On the contrary, presence of higher amounts of steroid hormones during pregnancy and in hormone replacement therapy may increase the rate of nicotine metabolism [231]. Another study reported that heavy use of tobacco smoking can reverse the advantageous use of oral estrogens for hot flashes, probably due to elevated clearance of estrogen because of heavy smoking. As higher dose of estrogen can increase breast cancer risk, therefore oral estrogen dose should not be increased to increase the estrogen efficacy in smokers [232].

Thus, gonadal hormone plays a crucial role in nicotine metabolism which is evident in pregnancy, menstruation as well as hormonal therapy suggesting the sex-different effect on nicotine pharmacokinetics.

8.2. Role of sex on nicotine pharmacodynamics:

8.2.1. Nicotinic receptor:

As previously mentioned, nicotine can upregulate the receptor density of nAChRs and comparative upregulation of nAChRs between male and female has been observed in different animal models. Studies have shown that chronic nicotine treatment upregulates nAChRs in the brains of male rats but not in female. However, the observed upregulation in male rats does not persist after a withdrawal period of 20 days. Sex differences in upregulation of nAChRs following chronic treatment with nicotine has been also observed in male mice compared to female mice using a specific radioligand [125I] IPH [233]. However, no sex difference in the upregulation of nAChRs has been observed when rats self-administer nicotine [234] suggesting the possible role of route of nicotine administration in inducing nicotinic receptor regulation in rodents [235].

As stated before, β2-nAChR is crucial for the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Therefore, sex difference in β2-nAChR availability and action may explain sex differences in tobacco smoking behaviors. Several studies have demonstrated the upregulation of β2-nAChRs level in nicotine treated male rodents compared to nicotine naïve counterparts [219, 236]. On the contrary, β2-nAChR upregulation has not been observed in nicotine exposed female rodents [237]. It has been demonstrated that a higher level of β2-nAChR was present in male smokers in the striatum, cortex, and cerebellum compared to male non-smokers, whereas female smokers have similar β2-nAChR density compared to non-smokers. These results suggest one possible neurochemical explanation for the sex difference in treatment response using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Interestingly, higher efficacy of NRT has been observed in male regarding smoking cessation compared to female [238]. As smoking-induced β2-nAChRs upregulation has been observed in men compared to women, it is likely that NRT may help to reduce β2-nAChRs in men down to non-smoker levels over time [239], yielding better smoking cessation efficacy.

8.2.2. DA receptor and 5HT transporters:

Several studies have identified sex differences in the regulatory effects of smoking on the mesolimbic DA system. Lower level of DA D2 receptor availability has been observed in the caudate and putamen of male smokers compared to non-smokers, although female group was not included in that study [240]. Another study reported that male smokers showed downregulation of DA D2/D3 level in the dorsal striatum compared to non-smokers [241]. Interestingly, similar levels of striatal DA D2/D3 availability was observed in both female smokers and female non-smokers [241] suggesting the importance of inclusion of female groups in experimental design. Okita et al reported that female smokers exhibited higher levels of midbrain DA D2/D3 receptor density compared to female non-smokers whereas no difference was observed in midbrain DA D2/D3 receptor availability between male smokers and non-smokers [242]. This study also suggests that upregulation of midbrain DA D2/D3 receptor availability in female smokers may mitigate against the downregulation of striatal DA D2/D3 receptors previously found in male smokers [242]. This helps explain the availability of DA D2/D3 receptor levels but does not describe the function of the DA system. Additionally, changes in DA release during in-vivo smoking was measured by novel PET technique revealing the consistent and rapid upregulation of DA level in ventral striatum of male smoker. On the contrary, no upregulation of DA level was observed in ventral striatum of female smokers [243]. The same study revealed that women respond faster to smoking than men in a discrete subregion of the dorsal putamen [243]. These findings suggest that male tobacco smokers generally exhibit lower D2 availability and higher DA release in the striatum, while female tobacco smokers show higher D2 availability in the midbrain and lower DA release in the striatum [239]. Future, controlled studies are needed to determine the influence of sex on dopamine reward pathways in smokers.

In addition, smoking can increase brain serotonin (5HT) levels and may alter expression and function of 5HT transporters. Sex hormones can modulate 5HT transporters indicating the role of sex difference on transporter function in smokers. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and [123I] β-CIT were used to label DA and 5HT transporters in brain where smokers showed higher uptake of [123I] β-CIT compared to non-smokers. Higher uptake in the striatum (10%), diencephalon (15%), and brainstem (15%) have been observed in females compared to males, regardless of smoking status. Although brainstem uptake was found to be 20% higher in male smokers and only 5% in female smokers compared to nonsmokers, sex and smoking interaction was not significant. These results demonstrate higher availability of DA and 5-HT transporter in women relative to men and no overall smoking effect with the exception of a moderate elevation in brainstem 5-HT transporters in male smokers. Brainstem 5-HT transporters may be regulated by smoking in a sex-specific manner [244].

8.2.3. Locomotor activity:

Nicotine effects on the DA system are associated with altered locomotor activity. It has been observed long before that nicotine stimulated locomotor activity in females however no effect was observed in males [245]. The impact of nicotine on locomotor activity involves both stimulant and depressant action [246]. Extracellular DA level has been found to be increased in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) following systemically administered nicotine [247]. Moreover, nicotine infusions into the ventral tegmental area resulted in enhanced locomotor activation [248] and this locomotor activity can be lessened by lesioning the ascending mesolimbic DA pathway [249]. These studies confirm the association of nicotine induced locomotor activity through the dopaminergic system and this dopaminergic system is controlled by hormonal environment. Studies have shown that estrogens and progesterone can regulate the function of DA systems in a complex manner. Estrogens can also increase nicotine-induced DA release in striatal slices in the brains of ovariectomized female rats [250]. Several studies have investigated the effects of sex and ovarian hormone on the nicotine effect on locomotor activity. Kanyt et al reported about acute and chronic effect of nicotine on locomotor activity in male, female, and ovariectomized hooded rats in series of experiments. This study showed that female rats experienced higher locomotor activity compared to male rates. Acute administration of nicotine reduced locomotor activity which was found slightly higher in female rats than male. Daily nicotine administration for 21 days resulted in similar and gradual increase in locomotor activity in both male and female [251]. In another experiment of the same study, ovariectomized rats were primed with 17-β-estradiol and progesterone. Acute administration of nicotine showed reduced activity in both groups in similar way. However, chronic nicotine administration for 21 days produced enhanced activity as a function of both chronic nicotine and hormonal priming. This study clearly suggests the role ovarian hormones on the chronic locomotor-activating effect of nicotine [251]. Other studies have reported significant reduction in spontaneous locomotor activity in nicotine treated female group compared to male [252, 253]. Also, an earlier study reported that lower sensitivity to nicotine’s motor depressant effects was observed in females compared to males [254].

Some studies have examined the effect of nicotine on locomotor activity during adolescent periods including both sexes. Higher locomotor activity was observed in female rats compared to male rats at low dose of nicotine injection [255]. However, Faraday et al reported contradictory results demonstrating higher locomotor activity in adolescent males compared to females when single dose nicotine was administered with minipumps [256]. Another study demonstrated that lower dose of nicotine administration caused decreased locomotor activity in female than male, using osmotic mini pumps [257].

Even though the nicotine-exposed adolescent demonstrated contradictory results, it is apparent that females are more sensitive to the nicotine induced locomotor activity compared to male, and most likely, ovarian hormones play a role in this greater responsivity. Future, experimental design should also focus on acute vs. chronic nicotine dosing when interpreting effects on locomotor activity.

8.2.4. Cognitive effects:

The nAChRs are present in different brain region including cortex, striatum, and ventral tegmental area which are critical for cognitive function and addiction [235]. Usually, cognitive function is similar in male and female humans however, task dependent sex differences have been observed [258]. Cognitive task performance depends not only on cognitive ability but also on cognitive style and behavioral strategy. Moreover, cognitive style or strategy can be affected by several factors including age, sex, hormonal influences and pharmacological manipulations [235]. Several studies have demonstrated sex difference in cognitive tasks and problem-solving strategies [259–261]. Klingenberg et al reported that males follow impulsive-global strategy whereas females prefer a reflective and sequential task-solving strategy which made them slower but accurate in problem solving [260]. Several studies have explored the effect of sex and nicotine on cognitive function. Algan et al reported that smoking has a gender-specific effect on cognitive function. Better verbal task performance was observed in males while increased subjective confidence was found in females, thus impacting the preferred cognitive strategies for problem solving [262]. Alteration of ‘no-response’ was observed in female due to smoking. Female nonsmokers showed higher no-response rate than males, while female smokers responded to almost all the stimuli presented in both verbal and spatial cognitive tasks. However, no smoking-effect was observed on the ‘no-response’ rate in males, suggesting the impact of smoking on females, such that their approach to the solution of a problem was modified [262]. Another study on rats showed sex difference effects of nicotine on cognitive function and strategy. This study measured cognitive function using water maze involving both navigational and visual cues. Without nicotine exposure, female rats showed different strategies using visual cues to find the platform than males, however nicotine treated female group exhibited a more male-like strategy to find the platform suggesting the nicotine effect on shifting strategy in female rats in problem solving and cognitive task [263].

In addition to altering cognitive strategy, enhanced performance in cognitive tasks by nicotine exposure was observed in several studies using both sexes. Yilmaz et al demonstrated that cognitive function in rats can be improved by nicotine during the acquisition phase of active avoidance learning trials in a dose-dependent manner. It was observed that male rats benefited from nicotine at all doses tested, whereas female rates experienced deteriorated learning performance at the higher dose, indicating the effect of nicotine on active avoidance in a sex and dose-dependent manner [264]. A recent cohort study involving around 70,000 participant also reported that smoking is associated with higher learning performance in women compared to men suggesting the role of nicotine in sex-difference on verbal learning and memory function [265].

Surprisingly, tobacco abstinence has also showed sex-difference effects on memory and cognitive function. A pilot study comprised of 25 participants (moderate to heavy smokers) examined how 24 hours tobacco abstinence affects cognitive function in male and female. Tobacco abstinence significantly deteriorated memory performance under full attention conditions for males but not for females, suggesting possible sex differences in the cognitive effects of tobacco abstinence [266].

The studies summarized above suggest an apparent sex-difference impact of nicotine on cognitive function. However, other factors including type of test, route of nicotine administration, species, strains, and age of animals should be considered to evaluate sex-difference effect of nicotine on cognitive and memory function.

8.2.5. Smoking cessation and withdrawal:

There are several studies focused on sex differences in smoking cessation and withdrawal involving several factors [267, 268]. Although tobacco smoking prevalence has been declining over the decades, interestingly this decline is less prominent in female compared to male. Some studies reported that women faced more difficulties in smoking cessation compared to men in clinical trials [269, 270]. Women are observed to be less successful and maintain abstinence for a shortened period of time compared to men [235]. The sex-difference regarding smoking cessation becomes even more evident with nicotine replacement therapy. It has been suggested in several studies that nicotine can be less reinforcing relative to nonpharmacological aspects of smoking [271–273]. Poorer pharmacotherapy outcome has been reported in women compared to men, which can be related to nicotine addiction as well as depression in women [274]. However, the reasons behind sex differences are yet to be elucidated. Figure 1 summarizes the impact of sex on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nicotine.

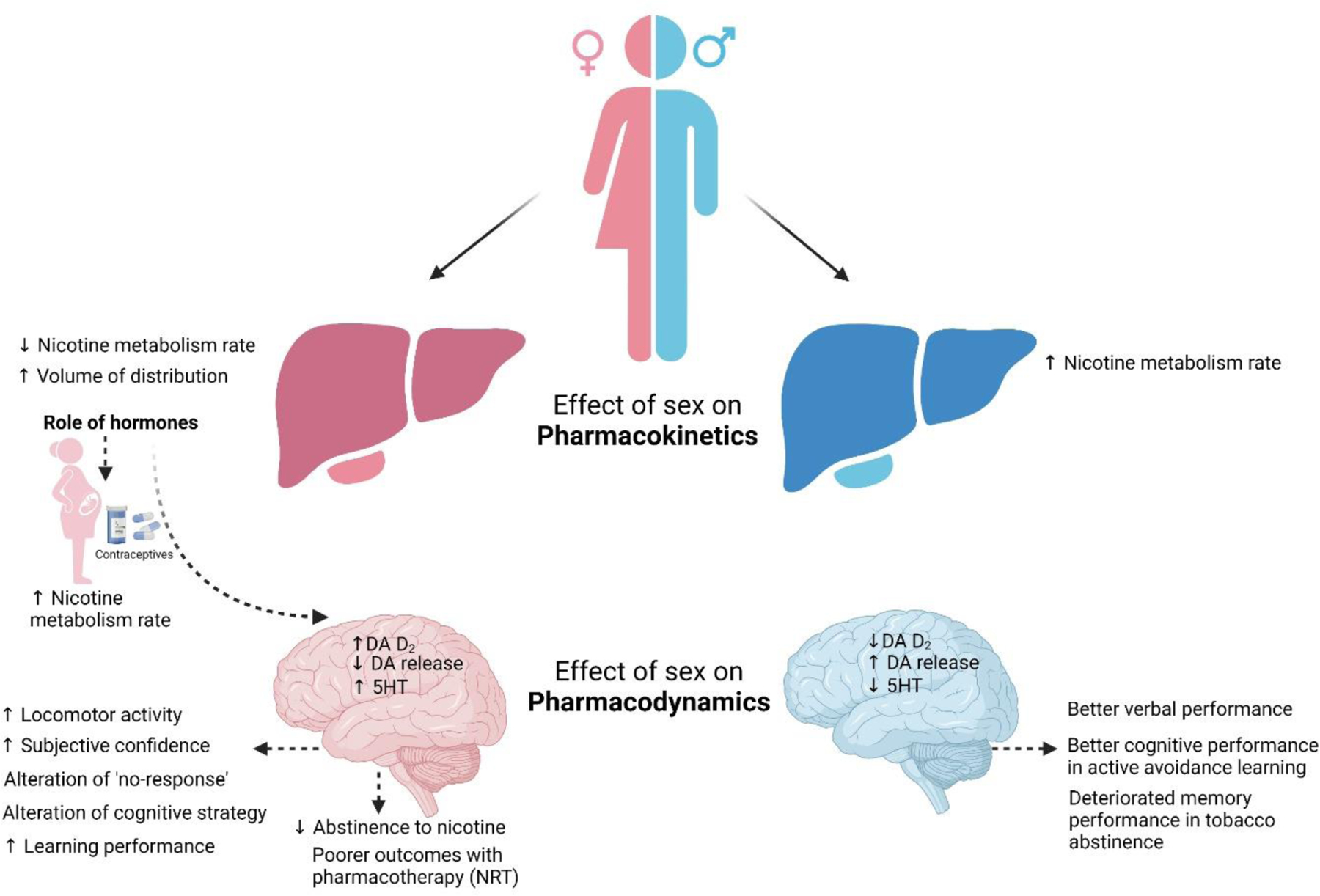

Figure 1:

Role of sex on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nicotine. (DA: Dopamine, DA D2: Dopamine receptor 2, 5 HT: 5 Hydroxytryptamine or serotonin, NRT: nicotine replacement therapy)

9. Role of age on nicotine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics:

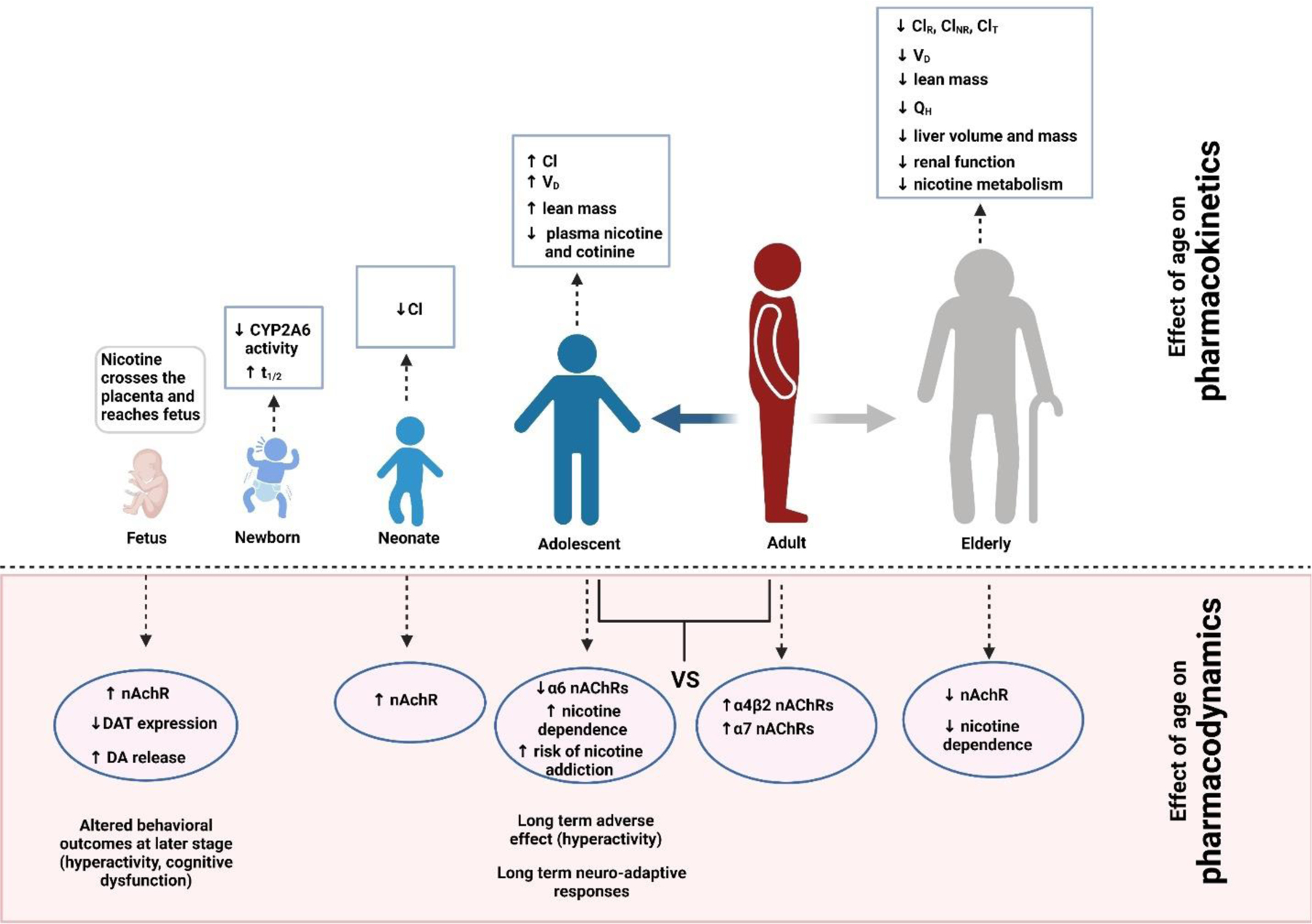

9.1. Role of age on nicotine pharmacokinetics:

Age related physiological changes can alter pharmacokinetic processes in several ways which ultimately affect drug availability and action. Pharmacokinetic parameters including absorption [275], distribution [276, 277], excretion [278], and metabolism [279] can be altered by age. Nicotine is no exception of this. Studies have shown that age has significant effect on nicotine pharmacokinetics. Reduced clearance of nicotine has been observed in elderly people (> 65 age) [277] and neonates [280]. However, no differences in nicotine pharmacokinetics have been observed between human adolescents and adults [281, 282]. On the contrary, lower level of plasma nicotine and cotinine was observed in adolescent rats compared to adult rats [283]. Craig et al., investigated the effects of age (adolescence vs adult) on nicotine pharmacokinetics and subsequently the plasma and brain levels of nicotine and its metabolites [284]. Nicotine was administered by SC or IV route to early adolescent and adult rats. Lower levels of nicotine, metabolites cotinine, and nicotine-19-N-oxide in plasma and brain of early adolescent rats compared to adult rats were found at different time points following SC nicotine administration which resulted in lower area under the plasma concentration-time curve. Similar results were observed following IV nicotine administration, suggesting a substantial age difference in nicotine pharmacokinetics [284]. The changes in pharmacokinetics of nicotine depends on age related changes in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination.

Distribution:

Body mass composition plays an important role in nicotine distribution and this parameter changes with age. Younger animals have a higher ratio of lean to fatty mass than older animals [285]. As nicotine primarily distributes into lean mass, therefore a change in this body mass composition due to age could potentially affect nicotine’s volume of distribution [277]. For instance, as adolescent animals tend to have primarily lean body mass, they would be expected to have a larger volume of distribution, relative to their body weight, for nicotine, resulting in lower plasma nicotine levels [284, 286]. Moreover, decreased volume of distribution at steady state is observed in the elderly subjects and could be due to age-related decrease in lean body mass [287, 288].

Hepatic clearance:

Age is considered as an important factor affecting CYP2A6 activity. Different studies have reported that CYP2A6 activity increases with increased age [289, 290]. Johnstone et al demonstrated that metabolic ration (3OH/COT) was marginally increased with age [291]. Increased CYP2A6 activity with age has been observed in in-vitro study using microsomes [292]. However, some studies have reported contradictory results on effect of age on nicotine metabolism. Surprisingly, it has been observed that nicotine clearance was decreased in elderly (age > 65) compared to adults [293]. In case of newborn, prolonged elimination half-life of nicotine but not cotinine was found compared to adult, suggesting the lower CYP2A6 activity or different specificity in newborn [294]. Studies have also suggested decreased renal clearance, non-renal clearance, and total clearance of nicotine in elderly population compared to adults. Since around 80% of nicotine is cleared by hepatic metabolism [295], lower non-renal clearance suggests a decreased hepatic extraction of nicotine in the elderly population. Reduced hepatic extraction could be due to reduced hepatic blood flow in elderly subjects. Moreover, liver volume and mass also decrease with age [296]. However, nicotine is a high extraction ration drug and hence it is speculated that its clearance is less affected by hepatic enzyme expression and activity [185]. Therefore, the faster clearance of nicotine observed in younger animals could be due to increased blood flow in liver [297].

Renal clearance: