Abstract

Current therapy for leishmaniasis is unsatisfactory. Efficacious and safe oral therapy would be ideal. We examined the efficacy of SCH 56592, an investigational triazole antifungal agent, against cutaneous infection with Leishmania amazonensis and visceral infection with Leishmania donovani in BALB/c mice. Mice were infected in the ear pinna and tail with L. amazonensis promastigotes and were treated with oral SCH 56592 or intraperitoneal amphotericin B for 21 days. At doses of 60 and 30 mg/kg/day, SCH 56592 was highly efficacious in treating cutaneous disease, and at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day, it was superior to amphotericin B at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day. The means of tail lesion sizes were 0.32 ± 0.12, 0.11 ± 0.06, 0.17 ± 0.07, and 0.19 ± 0.08 mm for controls, SCH 56592 at 60 and 30 mg/kg/day, and amphotericin B recipients, respectively (P = 0.0003, 0.005, and 0.01, respectively). Parasite burden in draining lymph nodes confirmed these efficacy findings. In visceral leishmaniasis due to L. donovani infection, mice treated with SCH 56592 showed a 0.5- to 1-log-unit reduction in parasite burdens in the liver and the spleen compared to untreated mice. Amphotericin B at 1 mg/kg/day was superior to SCH 56592 in the treatment of visceral infection, with a 2-log-unit reduction in parasite burdens in both the liver and spleen. These studies indicate very good activity of SCH 56592 against cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L. amazonensis infection and, to a lesser degree, against visceral leishmaniasis due to L. donovani infection in susceptible BALB/c mice.

The protozoa of the genus Leishmania, which are distributed throughout the world, are the cause of various clinical syndromes. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is usually fatal if untreated (3). Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) can be associated with significant morbidity and occasional deforming scars. Pentavalent antimonial compounds (sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate) have been the drugs of first choice for decades for the treatment of these disorders. These drugs are parenteral and associated with significant side effects (14). Pentamidine and amphotericin B are other parenteral alternatives that may cause significant side effects, such as renal toxicity and pancreatitis (7). Antimonial compounds are also associated with significant failure and relapse rates, especially in immunocompromised hosts (2, 9, 13).

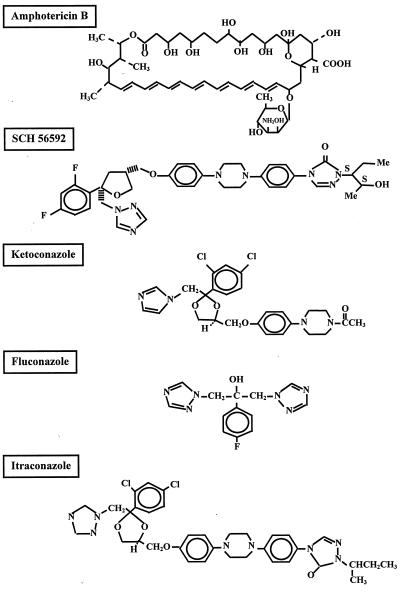

The search for safe and efficacious oral therapy has been ongoing for more than 2 decades. The azole antifungals ketoconazole and itraconazole have been used to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis with variable success rates (5, 6, 10). There have been conflicting reports of the success and failure of azoles in the treatment of VL (8, 12). Imidazole and triazole antifungals (Fig. 1) inhibit C-14 demethylation of lanosterol, which interferes with the production of leishmanial ergosterol, an essential component of their membrane structure (4).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of amphotericin B, SCH 56592, and other currently available azoles.

SCH 56592 (Schering-Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, N.J.) is an investigational triazole with broad-spectrum antifungal activity (Fig. 1) (11). We tested the activity of SCH 56592 against Leishmania promastigotes in vitro and against experimental CL caused by Leishmania amazonensis infection and VL caused by Leishmania donovani infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

L. donovani 1S (MHOM/SD/001S-2D) and L. amazonensis JOSEPHA were used for the in vitro and in vivo studies. Leishmania major KK, Leishmania mexicana 68 and 390 (gifts from F. Andrade Narvaez, Merida, Mexico), and Leishmania panamensis LS94 and L334 (gifts from B. Travi, CIDEIM, Cali, Colombia) were included in the in vitro testing. Parasites, in stationary phase, were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, were counted, and were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline at the appropriate concentration prior to infection.

Animals.

Age-matched 4- to 6-week-old female inbred BALB/c nu/+ mice (Veterinary Medical Unit breeding colony of the Audie Murphy Veterans Administration Hospital, San Antonio, Tex.) were used in the L. donovani infections. Male BALB/c nu/+ mice were used in the L. amazonensis study. Ten (L. amazonensis study) or 16 (L. donovani study) mice were included in each treatment or control group and were housed in populations of up to five per cage with free access to water and food.

Drugs.

SCH 56592 is an investigational triazole antifungal provided by Schering-Plough Research Institute. The drug was reconstituted from powder in 0.3% Noble agar and was given in 0.2-ml volumes orally by gavage. Amphotericin B was purchased commercially (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.) and was injected intraperitoneally in 0.2-ml doses.

In vitro susceptibility.

In vitro testing of Leishmania promastigotes was performed as described previously (1). In brief, Leishmania promastigotes were maintained in Grace’s insect culture media and were harvested and counted with a hemacytometer. Promastigotes (5 × 106/ml) were incubated at 26°C in 250 μl of medium per well containing twofold dilutions of each drug (0.125 to 8 μg/ml for amphotericin B and 0.25 to 32 μg/ml for SCH 56592 and fluconazole) and control media in microwell plates. The minimum protozoacidal concentration (MPC), as assessed by flagellar motility under indirect microscopy, was defined as the lowest concentration that reduced the number of viable promastigotes with respect to simultaneously growing controls by >90% after 18 h of incubation with the drug. In a few experiments, parasite death was also assessed by a [3H]thymidine incorporation assay.

L. amazonensis study.

Five groups of 10 male inbred BALB/c nu/+ mice were selected randomly to receive SCH 56592 at doses of 60, 30, and 15 mg/kg orally; to receive amphotericin B at a dose of 1 mg/kg intraperitoneally; or to receive 0.3% Noble agar orally. Mice were injected with 103 promastigotes of L. amazoniensis in a 0.01-ml volume into the right ear pinna and 105 promastigotes of L. amazoniensis in a 0.02-ml volume injected subcutaneously into the proximal third of the tail. Treatments were started on the third day postinfection and were continued for 21 days. Measurements of ear pinna thickness and tail lesion thickness, using a fine scale (Fowler Precision Tools, Lux Scientific Instrument Corp., New York, N.Y.), were taken on the 4th day postinfection, and these measurements were taken weekly for the following 6 weeks. Lesion size was considered as the difference between the thickness of the infected ear pinna and uninfected ear pinna. The size of the tail lesion was obtained by subtracting the average measurement of tail diameter at points just rostral and caudal to the lesion site from the maximal tail diameter at the lesion site. At day 44 postinfection, mice (eight per group) were terminated. Right ears and the external sacral lymph nodes (ESLN) (which drain the tail) were harvested, and the parasite burdens were determined by the quantitative limiting dilution method. Ear tissue was disrupted with a rotator homogenizer, and lymph nodes were harvested and homogenized between the frosted ends of sterile slides in 1 ml of complete culture medium and were diluted with the same medium to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. Fourfold serial dilutions of the homogenized tissue were then plated in a 96-well tissue culture plate and were cultured at 26°C for 3 weeks. The wells were examined for viable promastigotes at 3-day intervals, and the reciprocal of the highest dilution, which was positive for viable parasites, was considered to be the concentration of parasites in the organ (1).

L. donovani study.

Five groups of 16 female BALB/c mice were randomly selected to receive SCH 56592 at doses of 60, 30, and 15 mg/kg orally; to receive amphotericin B at a dose of 1 mg/kg intraperitoneally; or to receive 0.3% Noble agar orally. Mice were inoculated intravenously with 106 L. donovani promastigotes in a 0.2-ml volume through the lateral tail vein. Treatment was started on the 3rd day postinfection and was continued for 21 days. Half the mice (eight per group) were terminated at day 24, and the other half were terminated at day 44 postinfection. Hepatic and splenic parasite burdens were determined by the quantitative limiting dilution method described above (a 30-mg piece of tissue was homogenized in 3 ml of medium).

Statistical analysis.

For cutaneous infection, the means of the sizes of the ear and tail lesions of treatment groups and controls were compared using unpaired Student t test. For visceral infection, the mean log10 values of parasites per gram of liver and spleen of treatment groups and controls were compared using unpaired Student t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibility to SCH 56592, amphotericin B, and fluconazole.

In vitro, amphotericin B was more potent than SCH 56592 against Leishmania promastigotes of different species (Table 1). As previously reported, fluconazole was not effective against Leishmania promastigotes in culture media with MPCs of more than 32 μg/ml (1).

TABLE 1.

MPCs of SCH 56592, amphotericin B, and fluconazole against Leishmania spp.a

| Organism | Concn (μg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampho B | SCH 56592 | Fluconazole | |

| L. donovani | 0.5 | 16 | >32 |

| L. amazonensis | 0.5 | 16 | >32 |

| L. major | 0.125 | 8 | >32 |

| L. mexicana 68 | 0.5 | 8 | >32 |

| L. mexicana 390 | 1.0 | 16 | >32 |

| L. panamensis L334 | 0.25 | 8 | >32 |

| L. panamensis LS94 | 0.25 | 16 | >32 |

MPC of the drug is defined as the concentration which results in 90% inhibition of promastigote motility after 18 h of incubation.

Efficacy of SCH 56592 in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis.

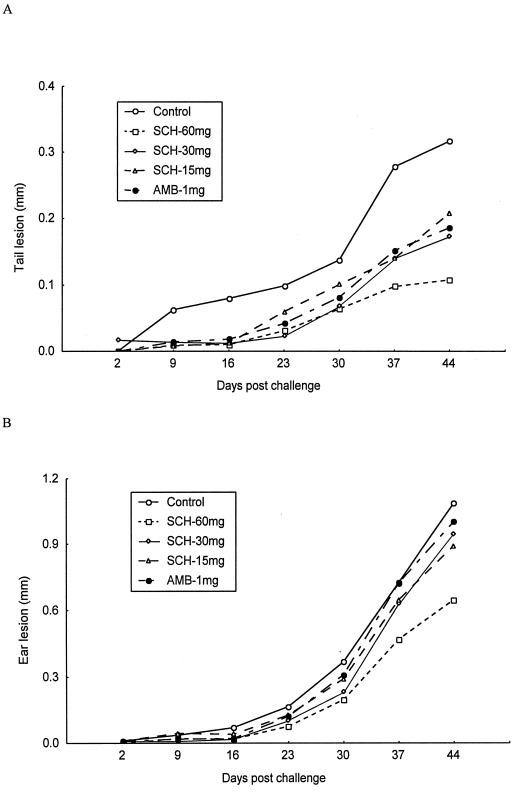

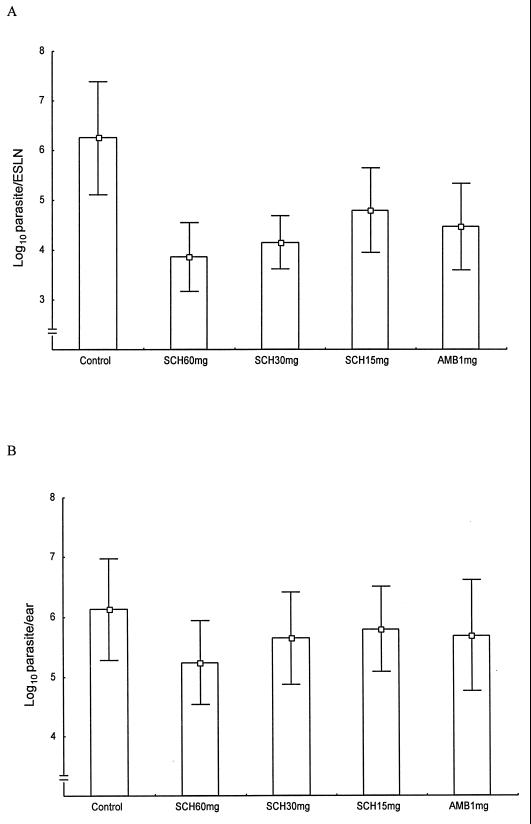

Six weeks postinfection with L. amazonensis promastigotes, tail lesions of the control group were significantly larger than those of any of the treatment groups. Lesion sizes were 0.32 ± 0.12, 0.11 ± 0.06, 0.17 ± 0.07, 0.21 ± 0.06, and 0.19 ± 0.08 mm for controls; SCH 56592 at 60, 30, and 15 mg/kg/day; and amphotericin B recipients, respectively (P = 0.0003, 0.005, 0.02, and 0.01, respectively). SCH 56592 at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day was superior to amphotericin B at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day (P = 0.03) (Fig. 2A). Parasite burdens in the ESLN of all treatment groups were significantly lower than the burdens in controls. The mean log10 values of parasites per ESLN were 6.25 ± 1.14, 3.86 ± 0.69, 4.16 ± 0.53, 4.80 ± 0.84, and 4.47 ± 0.87 for controls; SCH 56592 at 60, 30, and 15 mg/kg/day; and amphotericin B recipients, respectively (P = 0.0002, 0.0003, 0.01, and 0.003, respectively) (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 2.

Graph of the efficacy of a 21-day treatment course with SCH 56592 or amphotericin B in experimental CL caused by L. amazonensis infection. Sizes of tail lesions are shown in panel A and ear pinna lesions are shown in panel B for treated and untreated control mice. Treatments were started on the 3rd day postinfection and were continued for 21 days. The ear lesion size was considered as the difference between the thicknesses of the infected and uninfected ear pinnae. The size of the tail lesion was obtained by subtracting the average tail diameter at points just rostral and caudal to the lesion site from the maximal tail diameter at the lesion site.

FIG. 3.

Efficacy of a 21-day treatment course with SCH 56592 or amphotericin B in experimental CL caused by L. amazonensis. Parasite burdens in the ESLN are shown in panel A, and burdens in the ear are shown in panel B.

In ear infections, only recipients of SCH 56592 at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day had significantly smaller lesion sizes than controls. Lesion sizes were 1.09 ± 0.47 mm for controls, 0.65 ± 0.20 mm for groups treated with SCH 56592 at 60 mg, 0.95 ± 0.38 mm for groups treated with SCH 56592 at 30 mg, 0.90 ± 0.37 mm for groups treated with SCH 56592 at 15 mg/kg/day, and 1.0 ± 0.32 mm for groups treated with amphotericin B (P = 0.03 for SCH 56592 at 60 mg/kg/day) (Fig. 2B). Parasite burdens in the ear were lower only in the recipients of SCH 56592 at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day. The mean log10 values of parasites per ear were 6.13 ± 0.84, 5.24 ± 0.70, 5.65 ± 0.77, 5.80 ± 0.71, and 5.69 ± 0.93 for controls; SCH 56592 at 60, 30, and 15 mg/kg/day; and amphotericin B recipients, respectively (P = 0.04 for SCH 56592 at 60 mg/kg/day) (Fig. 3B).

Efficacy of SCH 56592 in experimental VL.

L. donovani-infected mice were treated for 21 days. Visceral parasite burdens were determined at days 24 and 44 postinfection. Table 2 summarizes the parasite loads in the liver and spleen of treated and untreated mice. At a dose of 30 mg/kg/day, SCH56592 reduced parasite burdens in the liver and spleen by 0.5 to 1 log unit (P < 0.05). Amphotericin B reduced parasite burdens by 2 log units in both liver and spleen (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in parasite loads at days 24 and 44 postinfection. All mice that received SCH 56592 at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day died within 14 days of therapy for an unexplained reason, possibly due to drug toxicity.

TABLE 2.

Parasite burdens on days 24 and 44 in the liver and spleen of L. donovani-infected mice treated for 21 days

| Treatment | Dose (mg/kg/day) | Day of tissue burden | Log10 of parasite/g of tissuea

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Spleen | |||

| None | 24 | 5.70 ± 0.55 | 5.53 ± 0.40 | |

| 44 | 5.15 ± 0.43 | 5.72 ± 0.24 | ||

| SCH56592 | 30 | 24 | 4.86 ± 0.53* | 4.82 ± 0.63* |

| 44 | 4.41 ± 0.81* | 4.86 ± 0.53* | ||

| SCH56592 | 15 | 24 | 5.47 ± 0.42 | 5.38 ± 0.27 |

| 44 | 5.15 ± 0.42 | 5.65 ± 0.32 | ||

| Amphotericin B | 1 | 24 | 3.88 ± 1.00** | 3.89 ± 0.60** |

| 44 | 3.52 ± 0.70** | 3.97 ± 0.39** | ||

Means ± standard deviations for eight mice. *, Statistically significant (P < 0.05); **, highly significant (P < 0.0001) compared to untreated mice.

DISCUSSION

Inconvenience, toxicity, and a significant relapse rate are major problems associated with the currently used parenteral drug therapy for the leishmaniases (2, 7, 9, 13). Efficacious and safe oral therapy is greatly needed. In this study, we examined a new, orally administered triazole antifungal drug, SCH 56592, against Leishmania. In vitro studies showed that SCH 56592 had modest activity, inferior to amphotericin B but substantially better than fluconazole, against leishmanial promastigotes. The in vitro activity of a drug against the promastigote stage may not necessarily correlate with its activity against intracellular amastigotes. Our in vivo studies demonstrated that SCH 56592 was efficacious in the treatment of experimental CL. The mechanism of action of SCH 56592 against Leishmania spp. is probably similar to those of other azole antifungals, i.e., inhibition of membrane sterol synthesis resulting in disruption of the cell membrane.

We studied the efficacy of SCH 56592 in an experimental model of CL caused by a highly virulent strain of L. amazonensis. Mice were infected at both relatively permissive (ear pinna) and nonpermissive (tail) sites (1), and the response to therapy was assessed by measurement of lesions and determination of parasite burdens in the ears and lymph nodes which drain the tail site of infection. SCH 56592, when used at higher doses (60 mg/kg/day), was superior to the standard, tolerated, doses of amphotericin B in reducing the size of cutaneous lesions. It is not clear if this superiority in treating cutaneous disease is related to leishmanicidal activity or, as is more likely, due to a better distribution of the drug to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The lower parasite burdens present in the ear tissue and lymph nodes in SCH 56592-treated mice were consistent with the results of the clinical response. The response observed in the ear infection was clearly less impressive than in the tail infection. This was previously observed in treated mice (1). In humans, leishmanial infections involving the ear are more chronic and progressive, and they are more difficult to treat than infections at other cutaneous sites (15). Amphotericin B demonstrated a reduced efficacy in treating cutaneous diseases. In future studies, it may be useful to compare SCH 56592 to other azoles to determine if it would be more efficacious than structurally related compounds.

In the model of VL due to L. donovani infection, SCH 56592 was modestly effective in reducing the parasite burdens in the liver and spleen compared to untreated controls. Amphotericin B was clearly superior to SCH 56592, resulting in reductions in parasite burdens of approximately 2 log units in the liver and spleen. These findings are consistent with the reported limited success achieved when treating patients with visceral disease with other azoles (12).

Our study indicates that SCH 56592 is efficacious against CL due to L. amazonensis infection and may serve as convenient oral therapy. However, this has to await formal toxicity testing. The study also indicates that SCH 56592 is less likely to be effective as a single drug in the treatment of VL. Perhaps this drug may be useful as part of a combination therapy for resistant disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Schering-Plough Research Institute and by funding from the Veterans Administration to P.C. Melby.

We are grateful to L. Najvar, R. Bocanegra, and E. Montalbo for their help with measurement of lesions and with dosing animals; A. Fothergill (Fungus Testing Laboratory, San Antonio, Tex.) for her help in preparing drugs for in vitro testing; and Weigou Zhao for his help with preparation of the culture media.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Abdely H M, Graybill J R, Bocanegra R, Najvar L, Montalbo E, Regen S L, Melby P C. Efficacies of KY62 against Leishmania amazonensis and Leishmania donovani in experimental murine cutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2542–2548. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvar J, Canavate C, Gutierrez-Solar B, Jimenez M, Laguna F, Lopez-Velez R, Molina R, Moreno J. Leishmania and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection: the first 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:298–319. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman J D. Human leishmaniasis: clinical, diagnostic, and chemotherapeutic developments in the last 10 years. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:684–703. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman J D, Goad L J, Beach D H, Holz G G., Jr Effects of ketoconazole on sterol biosynthesis by Leishmania mexicana mexicana amastigotes in murine macrophage tumor cells. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;20:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dan M, Verner E, el-On J, Zuckerman F, Michaeli D. Failure of oral ketoconazole to cure cutaneous ulcers caused by Leishmania braziliensis. Cutis. 1986;38:198–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dogra J, Saxena V N. Itraconazole and leishmaniasis: a randomised double-blind trial in cutaneous disease. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:1413–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(96)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasser R A, Jr, Magill A J, Oster C N, Franke E D, Grogl M, Berman J D. Pancreatitis induced by pentavalent antimonial agents during treatment of leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:83–90. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halim M A, Alfurayh O, Kalin M E, Dammas S, al-Eisa A, Damanhouri G. Successful treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with allopurinol plus ketoconazole in a renal transplant recipient after the occurrence of pancreatitis due to stibogluconate. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:397–399. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra M, Biswas U K, Jha A M, Khan A B. Amphotericin versus sodium stibogluconate in first-line treatment of Indian kala-azar. Lancet. 1994;344:1599–1600. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Momeni A Z, Jalayer T, Emamjomeh M, Bashardost N, Ghassemi R L, Meghdadi M, Javadi A, Aminjavaheri M. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with itraconazole. Randomized double-blind study. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:784–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oakley K L, Moore C B, Denning D W. In vitro activity of SCH-56592 and comparison with activities of amphotericin B and itraconazole against Aspergillus spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1124–1126. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rashid J R, Wasunna K M, Gachihi G S, Nyakundi P M, Mbugua J, Kirigi G. The efficacy and safety of ketoconazole in visceral leishmaniasis. East Afr Med J. 1994;71:392–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal E, Marty P, Poizot-Martin I, Reynes J, Pratlong F, Lafeuillade A, Jaubert D, Boulat O, Dereure J, Gambarelli F. Visceral leishmaniasis and HIV-1 co-infection in southern France. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Voorhis W C. Therapy and prophylaxis of systemic protozoan infections. Drugs. 1990;40:176–202. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199040020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton B C. American cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. In: Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R, editors. The leishmaniases in biology and medicine. II. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1987. p. 644. [Google Scholar]