Abstract

Sugary drink warnings are a promising policy for reducing sugary drink consumption, but it remains unknown how to design warnings to maximize their impact overall and among diverse population groups, including parents of Latino ethnicity and parents with low English use. In 2019, we randomized US parents of children ages 2-12 (n=1,078, 48% Latino ethnicity, 13% low English use) to one topic (one of four warnings, or a neutral control), which they viewed on three designs (text-only, icon, and graphic) to assess reactions to the various warnings on sugary drinks. All warning topics were perceived as more effective than the control (average differential effect [ADE] ranged from 1.77 to 1.84 [5-point Likert scale], all p<.001). All warning topics also led to greater thinking about harms of sugary drinks (all p<.001) and lower purchase intentions (all p<.01). Compared to text-only warnings, icon (ADE=.18) and graphic warnings (ADE=.30) elicited higher perceived message effectiveness, as well as greater thinking about the harms of sugary drinks, lower perceived healthfulness, and lower purchase intentions (all p<.001). The impact of icon warnings (vs. text warnings) was stronger for parents with low English use, compared to those with high English use (p=.024). Similarly, the impact of icon (vs. text warnings) was stronger for Latino parents than non-Latino parents (p=.034). This experimental study indicates that many warning topics hold promise for behavior change and including images with warnings could increase warning efficacy, particularly among Latino parents and parents with low English use.

Keywords: obesity, health policy, Latino/a health, Hispanic, warning labels, sugar-sweetened beverages

INTRODUCTION

Consumption of drinks with added sugar (“sugary drinks”) among US children and adults remains well above recommended levels, with 63% of children and 49% of adults consuming sugary drinks on a given day.1–3 Compared with non-Latino white populations, Latino children and adults consume more sugary drinks.4–6 Sugary drink consumption contributes to obesity, dental caries, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.7–10 Policy solutions that impact parents’ sugary drink purchasing behaviors could benefit both parents and children, since the vast majority of children’s total energy intake from sugary drinks comes from store-bought sugary drinks (rather than from school and other sources),11 and parental sugary drink consumption is positively associated with children’s sugary drink consumption.12,13

One possible policy solution to reduce parents’ purchases of sugary drinks for themselves and their children is requiring warnings on sugary drink containers and advertisements. Sugary drink warnings proposed or implemented have focused on a variety of different topics and designs. Topics include nutrient warnings that inform consumers that sugary drinks are high in sugar (per laws passed in countries including Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Peru, Israel, and Mexico14), and health warnings which indicate that sugary drinks increase disease risk (per legislation passed in San Francisco and introduced in seven US states15). Designs include text-only warnings (used in all proposed US policies), icon warnings with symbolic depictions of nutrients or health harms (used on products in Israel and on menus in New York City), and graphic warnings with photographic depictions (not yet proposed for sugary drinks, but used in cigarette warnings in over 100 countries).16 Warning policies also have used a variety of shapes, such as octagon-shaped warnings in Chile, Peru, Mexico, and Uruguay, versus rectangular labels used for US warnings on cigarettes and alcohol.

Despite the varied sugary drink warning approaches taken by governments, few studies have compared sugary drink warning features head-to-head. A handful of studies suggest that graphic sugary drink warnings are likely to be more effective than text warnings,17–19 but experiments have not examined sugary drink warnings with icons. Moreover, studies about sugary drink warnings have not focused on warnings’ potential impact on Latinos in the US, nor has research examined individuals with high English use compared to those with low English use. Evaluating impact across English language use is important to ensure sugary drink warnings that appear in English would not exacerbate disparities in sugary drink consumption4 and associated noncommunicable diseases. 20–15

This study examined the impact of warning topic, warning design, and warning shape on reactions to warnings and perceptions of sugary drinks among non-Latino parents and Latino parents with high English language use and low English language use. Informed by health behavior change theories and messaging frameworks,21–23 we examined key predictors of behavior change, including perceived message effectiveness, thinking about harms of sugary drinks, perceived healthfulness, and purchase intentions. We explored whether the impact of warning topic and design varied by level of English language use and Latino ethnicity.

METHODS

Participants

In October 2019, we recruited an online convenience sample to participate in an experiment. Recruitment occurred through CloudResearch Prime Panels, a survey research platform. Inclusion criteria were currently residing in the US, being at least 18 years old, and having at least one child between the ages of 2 and 12. Prior to participating in the study, participants provided electronic consent. Prime Panels used quota-based sampling when advertising to existing panel members, such that the sample comprised about half Latino and half non-Latino participants. Online convenience samples can yield highly generalizable findings for experiments, meaning that the direction and statistical significance of effects observed in experiments are very similar in convenience samples and nationally representative samples.24 Upon completing the study, participants received previously agreed upon incentives (e.g., redeemable points) from Prime Panels.

Stimuli development

The final warnings appear in eFigure 1. We created messages about five different topics: one nutrient warning about added sugar (based on nutrition labeling policies passed in countries including Chile, Peru, Uruguay, and Israel), three health warnings about outcomes that the epidemiological literature suggests may result from overconsumption of sugary drinks (heart damage, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain9,10,25), and one control message about littering (in line with previous labeling studies26,27). To create the warning messages, we modeled the language and sentence structure after the sugary drink warning ordinance passed in San Francisco.28 We included the marker word “WARNING” and stronger causal language (e.g., “contributes to” instead of “may contribute to”) given research highlighting that inclusion of these components could heighten the effectiveness of warnings.29,30 All messages were in English to mimic US state-level sugary drink product policies.

Next, we created three different warning designs: text-only warnings, icon warnings, and graphic warnings. Text-only warnings consisted of the warning message in white font, centered in a black square background. To create the graphic warnings, a professional designer identified stock photographs representing each of the topics. After vetting an initial set of warning topics and photographs with a stakeholder advisory board (comprised of nutrition epidemiologists, a weight stigma expert, a public health lawyer, and leaders from Latino health organizations), we conducted two rounds of quantitative image pre-testing using convenience samples of US adults recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (total n=861). For each warning topic, we selected the photograph rated as most discouraging participants from wanting to consume sugary drinks and created graphic warnings using those photographs. We selected the control image internally. To create the icon warnings, the professional designer created computer illustrations to match the photographs selected for each topic.

In addition to the main experimental factors described above (warning topic and design), we also created text-only warnings shown on octagon-shaped labels (octagon warnings) for all warning topics (but not for the neutral control). The octagon warnings looked identical to the text-only warnings except displayed in an octagon instead of a square, allowing us to examine the impact of label shape on participant reactions. We did not examine an octagon-shaped label for the control topic because we anticipated that the octagon shape might inherently convey warning-related information, and therefore would not be appropriate as a true control.

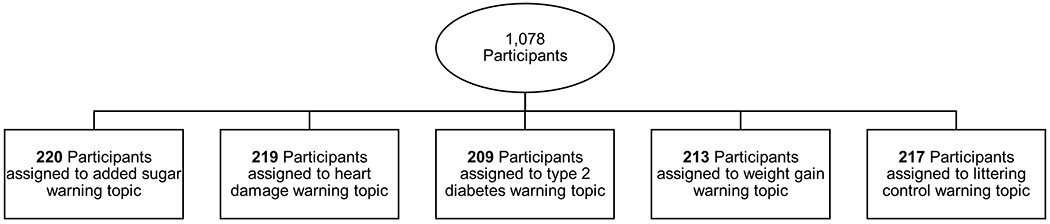

Procedures

We registered the study on AsPredicted.org: http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=sv6h6p before data collection and ClinicalTrials.gov after data collection (NCT04382599). Participants completed an online survey programmed using Qualtrics survey software. The experiment used a between-within subjects design. The survey automatically randomized participants (with simple allocation ratio) to one of the warning topics (i.e., added sugar, heart damage, type 2 diabetes, weight gain) or the control topic (littering) (see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram). Then, participants viewed the three warning designs (text-only, icon, and graphic) for their one randomized topic presented on square labels in a random order within subjects. Participants in the warning conditions additionally viewed the text-only octagon warning for their assigned topic (this warning was presented randomly within the set of warnings these participants viewed).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

Measures

Participants rated each warning using measures adapted from English-language surveys in previous studies. All items used Likert-style response options (ranging from 1-5) with a lower score indicating lower levels of the construct and a higher score indicating greater levels of the construct. The primary outcome was perceived message effectiveness,31 measured using three items: “This message makes me concerned about the health effects of drinking beverages with added sugar”; “This message makes drinking beverages with added sugar seem unpleasant to me”; and, “This message discourages me from wanting to drink beverages with added sugar.” We then averaged responses for the three items to create an average perceived message effectiveness scale (Cronbach’s α for all warning designs>.85). Perceived message effectiveness is sensitive to differences between warnings in online studies and is predictive of actual behavior change.32 Secondary outcomes, measured with single items, included thinking about the harms of sugary drink consumption (i.e., thinking about the harms),23 perceived healthfulness of sugary drinks for their child (i.e., perceived healthfulness),33,34 and intentions to purchase sugary drinks for their child (i.e., purchase intentions).35 After rating each warning, participants viewed all the warning designs in their assigned condition and were asked, “Which of these messages would discourage you most from wanting to drink beverages with added sugar?”

Participants chose to take the survey in either English or Spanish. A professional translation company translated survey items from English to Spanish. To ensure the items were well understood by Spanish-speaking participants, we conducted ten in-person cognitive interviews with native Spanish speakers in June 2019. These interviews were conducted in Spanish by a native Spanish-speaking team member, in the Research Triangle area of North Carolina. Exact item wording and response scales in both languages appear in eTable 1. Latino ethnicity was measured by asking participants if they were “of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin”.36 We measured English language use with the item, “In general, what language(s) do you read and speak?”37 with responses “more Spanish than English” and “Only Spanish” coded as low English language use and responses “only English,” “more English than Spanish,” and “both equally” coded as high English language use.

Analysis

Analyses used Stata/SE version 16 with two-tailed tests, a critical alpha of 0.05, and listwise deletion for missing data. We powered the study based on effect sizes from a meta-analysis estimating the impact of warnings on our primary outcome.38 We first examined whether randomization created equivalent groups using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA F-tests for continuous variables, examining all variables in Table 1. We predicted that, compared to a control, all warning topics would lead to greater perceived message effectiveness, more thinking about the harms, lower perceived healthfulness of sugary drinks, and lower purchase intentions. We also examined the predictions that, compared to text-only warnings, icon warnings and graphic warnings would lead to greater perceived message effectiveness, more thinking about the harms, lower perceived healthfulness, and lower purchase intentions.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=1,078)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-29 years | 238 | 22% |

| 30-39 years | 563 | 52% |

| 40-54 years | 259 | 24% |

| 55+ years | 15 | 1% |

| Mean in years (SD) | 35.3 | 7.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Man | 445 | 41% |

| Woman | 628 | 58% |

| Transgender or other | 5 | 0% |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight or heterosexual | 994 | 92% |

| Gay or lesbian | 24 | 2% |

| Bisexual | 49 | 5% |

| Other | 11 | 1% |

| Latino ethnicity | 514 | 48% |

| Race | ||

| White | 796 | 74% |

| Black or African American | 135 | 13% |

| Asian | 23 | 2% |

| Other/multiracial | 121 | 11% |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 | 0% |

| Pacific Islander | 2 | 0% |

| English language use | ||

| Low | 141 | 13% |

| High | 937 | 87% |

| Education | ||

| Less than a high school degree | 39 | 4% |

| High school degree | 473 | 44% |

| Four-year college degree | 428 | 40% |

| Graduate degree | 138 | 13% |

| Financial situation | ||

| Difficulty paying the bills no matter what | 144 | 13% |

| Have to cut back on things to pay the bills | 128 | 12% |

| Enough to pay bills, but little spare money to buy extra or special things | 425 | 39% |

| After paying bills, enough money for special things | 380 | 35% |

| Household income, annual | ||

| $0-$24,999 | 213 | 20% |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 288 | 27% |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 202 | 19% |

| $75,000+ | 375 | 35% |

| Number of children in household (0-18) | ||

| 1 | 381 | 35% |

| 2 | 416 | 39% |

| 3 | 184 | 17% |

| 4 or more | 97 | 9% |

| Used SNAP in the last year | 344 | 32% |

| History of disordered eating | 156 | 14% |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 37 | 3% |

| Healthy Weight (18.5-24.9) | 384 | 36% |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 327 | 31% |

| Has obesity (30 or above) | 314 | 30% |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 28.0 | 7.7 |

| Frequency of sugary drink consumption | ||

| 0 to 1 times per week | 279 | 26% |

| >1 to <7 times per week | 370 | 34% |

| 1 to 2 times per day | 205 | 19% |

| More than 2 times per day | 224 | 21% |

| Child’s frequency of sugary drink consumption1 | ||

| 0 to 1 times per week | 300 | 28% |

| >1 to <7 times per week | 425 | 39% |

| 1 to 2 times per day | 189 | 18% |

| More than 2 times per day | 164 | 15% |

| Language of survey administration | ||

| English | 924 | 86% |

| Spanish | 154 | 14% |

Asked about one child ages 2-12 with the most recent birthday.

Note. Characteristics did not differ by between-subjects experimental arms. Missing demographic data ranged from 0% to 1.5%.

For the analysis of each of the outcomes, we used a mixed effects linear model, treating the intercept as a random effect, to assess the relationship between experimental factors and the outcome. Predictors were warning design (within subjects, Level 1), topic (between subjects, Level 2), and the interaction between these two factors. If the interaction term was not significant, we presented the model without the interaction as our main model. In the main models, the control topic (littering) was the reference group for topic and text-only was the reference group for design. We used Wald tests to compare the remaining topics and designs to each other. We report average differential effects of each experimental factor on the outcomes as generated by the final models. We also report Cohen’s d statistic39 to put effect sizes into a common metric.

Next, we compared perceived message effectiveness ratings of the octagon text-only warning with the square text-only warning using a paired t-test, separately for each warning topic, to understand differences in outcomes based on warning shape. For each warning topic, we calculated the proportion of participants selecting each warning design as the design that most discouraged them from wanting to consume sugary drinks, using independent samples z-tests to compare the proportions.

Finally, in exploratory analyses (not pre-specified), we examined whether English language use and Latino ethnicity moderated the impact of warning topic and warning design on perceived message effectiveness. To test these interactions, we ran two separate models, one for each moderator; these models included a two-way interaction between topic and design, as well the three-way interaction between the moderator, topic, and design. We then computed and compared the average marginal effects of each topic and design (relative to the littering and text-only controls, respectively) at each level of the moderator.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Participants had a mean age of 35.3 years (Table 1). Most participants were women (58%) and white (74%), with almost half of the sample identifying as Latino (48%). About half of participants had a high school degree or less (48%) and about half reported an annual household income below $50,000 (47%). Most participants (87%) had high English language use and consumed sugary beverages at least once per week (74%). Participant characteristics were equivalent across experimental arms (all p>.37).

Impact of warning topic

All nutrient and health warning topics (added sugar, heart damage, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain) were perceived as more effective than the control (average differential effect [ADE] ranged from 1.77 to 1.84, all p<.001; Table 2; raw means and SDs appear in eTable 2; Cohen’s d’s appear in eTable 3). All warning topics also led parents to think more about the harms of sugary drinks compared to the control (ADE ranged from 1.29 to 1.42, all p<.001), Added sugar was the only warning topic that led to lower perceived healthfulness of one’s child drinking sugary drinks daily (ADE=−.33, p;=.003), All warning topics led to lower intentions to purchase sugary drinks for one’s child in the next four weeks (ADE ranged from −.47 to −.35, all p<.01). The nutrient and health warning topics did not differ from each other on any outcomes (all Wald test p>.229). English language use and Latino ethnicity did not moderate the impact of warning topic on perceived message effectiveness (all p>.05).

Table 2.

Effects of warning topic and warning design on study outcomes, n=1,078.

| Perceived message effectiveness | Thinking about the harms of sugary drinks for child | Perceived healthfulness of sugary drinks for child | Intentions to purchase sugary drinks for child | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| ADE | SE | p | ADE | SE | p | ADE | SE | p | ADE | SE | p | |

| Warning topic | ||||||||||||

| Control (reference) | ||||||||||||

| Added sugar | 1.84 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 0.10 | <0.001 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 0.003 | −0.42 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Heart damage | 1.77 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 0.10 | <0.001 | −0.14 | 0.11 | 0.196 | −0.35 | 0.11 | 0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 1.77 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 0.10 | <0.001 | −0.21 | 0.11 | 0.059 | −0.47 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Weight gain | 1.81 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 0.10 | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.11 | 0.274 | −0.35 | 0.11 | 0.001 |

| Warning design | ||||||||||||

| Text (reference) | ||||||||||||

| Icon | 0.18 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.10 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.11 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Graphic | 0.30a | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.35a | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.18a | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.16a | 0.02 | <0.001 |

Note. ADE=average differential effect from mixed effects linear regression models. SE=standard error. Excluding littering (control), Nutrient and health warning topics (i.e., added sugar, heart damage, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain not different from each other for any outcome.

Graphic different from icon at p<.05 level.

Impact of warning design

Icon and graphic warnings led to greater perceived message effectiveness than text-only warnings (ADE=.18 and .30 for icon and graphic, respectively, both p<.001; Table 2). Compared to text-only warnings, icon and graphic warnings also led to greater thinking about the health harms of sugary drinks (ADE=.16 and .35, both p<.001), lower perceived healthfulness of one’s child drinking sugary drinks daily (ADE=−.10 and −.18, both p<.001), and lower intentions to purchase sugary drinks for one’s child in the next four weeks (ADE=−.11 and −.16, both p<.001). Graphic warnings elicited reactions that were stronger in magnitude than icon warnings for all outcomes (Wald test ps<.05).

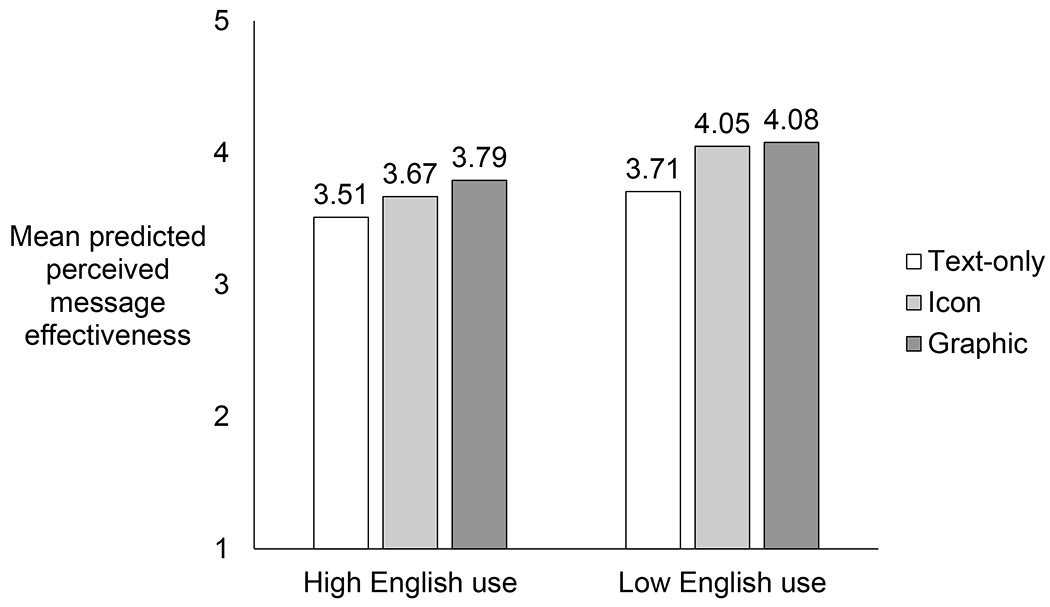

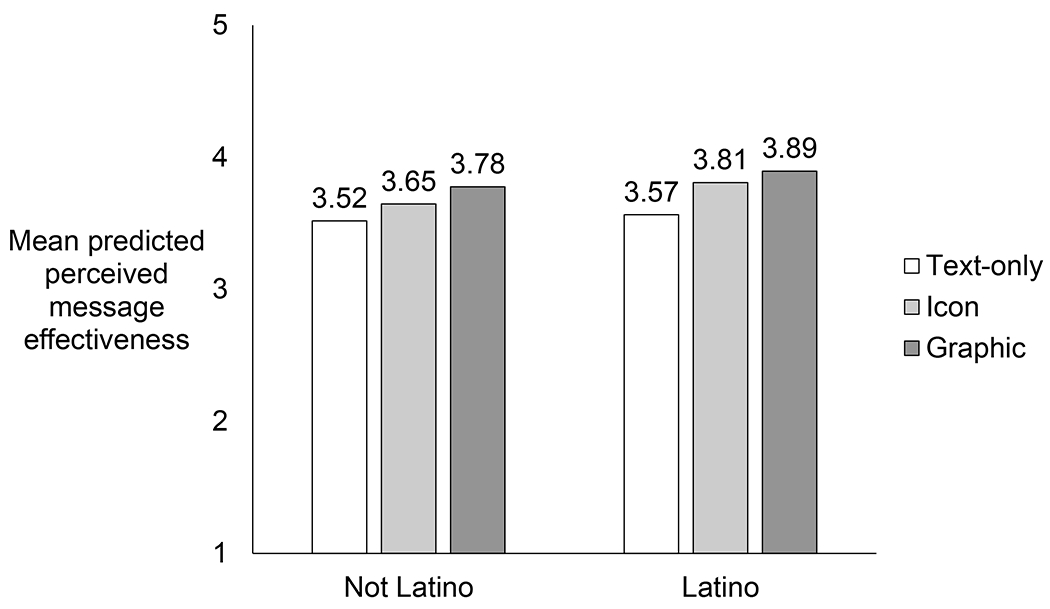

Moderation analyses revealed the impact of icon warnings (vs. text-only warnings) was stronger for participants with low English use compared to those with high English use (difference in average effect of icon relative to text for low vs. high English use participants, 0.182, p=.024; Figure 2, Panel A; eTable 4). These analyses also highlighted higher perceived message effectiveness among people with low English use compared to those with high English use (Figure 2, Panel A). Latino ethnicity also moderated the impact of warning design on perceived message effectiveness, following the same pattern as low English use (difference in average effect of icon relative to text for Latino vs. non-Latino participants, 0.116, p=.034; Figure 2, Panel B).

Figure 2.

Effects of graphic and icon warnings relative to text-only by English language use (Panel A), p=.024 for moderation of icon vs. text-only warnings, p=.233 for moderation of graphic vs. text-only warnings; and by Latino ethnicity (Panel B), p=.034 for moderation of icon vs. text-only warnings, p=.19 for moderation of graphic vs. text-only warnings.

Participants assigned to the nutrient or health warning topics also rated a text-only octagon warning on perceived message effectiveness. The text-only octagon warning did not differ from the text-only square warning for added sugar, heart damage, or weight gain (all p>.219). For the type 2 diabetes warning topic, participants perceived the octagon warning as more effective than the text-only square warning (mean=3.94 vs. 3.79, p=.007), When asked which warning most discouraged them from wanting to consume sugary drinks, a majority of participants selected the graphic warnings (range, 56% for added sugar to 82% for type 2 diabetes; eFigure 2).

DISCUSSION

In a large, sample of Latino and non-Latino US parents, we found that parents perceived all sugary drink warning topics, including added sugar, heart damage, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain, to be more effective than a control message. All warning topics also led parents to think more about the health effects of sugary drinks for their child and led to lower intentions to purchase sugary drinks for their child. This study adds to evidence from a recent meta-analysis of experiments finding that sugary drink warnings led to reductions in both hypothetical and real-stakes sugary drink purchase and consumption behavior.40 Moreover, warning topics performed equally well for Latino parents and non-Latino parents, as well as for people with varying levels of English language use. These findings add to a growing body of research suggesting that warnings work well across diverse populations.41–44 Taken together, these findings are very promising for sugary drink warning policies.

We found that warnings about both a nutrient (i.e., added sugar) and health problems were similarly effective, which suggests that policymakers and regulatory agencies have several potentially effective options to consider when crafting warning messages. Our finding that nutrient and health warnings led to similar reductions in purchase intentions contrasts with a meta-analysis that found that health warnings were more effective than nutrient warnings at reducing hypothetical sugary drink purchases. One possible explanation for the difference between our study and the meta-analysis is that many previous studies have tested health warnings that describe multiple health harms,29,35,45 which could heighten their impact relative to nutrient warnings. More research is needed to understand differences in consumer responses to nutrient and health warnings, as well as the effects of a wider variety of possible warning topics (e.g., sugary drinks’ link with dental caries). While our study only included one health topic per warning, future studies should examine the ideal number of topics to include in warnings, given studies of cigarette warnings suggesting that including multiple health effects in messages could increase their impact.46 We also found that most warning topics (except “added sugar”) did not change perceived healthfulness of sugary drinks, in contrast with the meta-analysis,40 which found that warnings lowered perceived product healthfulness. One possible explanation is that, in contrast with our study, other studies have shown warnings mocked up on a variety of products. Warnings could possibly have a stronger impact on perceived healthfulness of sugary drink types that are marketed to appear healthful, such as fruit drinks.47–49

Our experiment revealed that images enhanced warnings’ effectiveness. Compared to text-only warnings, icon and graphic warnings led to greater perceived message effectiveness, thinking about the risks of sugary drinks for one’s child, lower perceived healthfulness of sugary drinks, and lower purchase intentions (a key mediator of behavior change in the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action).21,50 Additionally, graphic warnings out-performed icon warnings on all of the outcomes. These findings add to evidence from the tobacco literature demonstrating the effectiveness of graphic warnings26,38,51–53 and build on studies highlighting the promise of graphic sugary drink warnings.17,18,54 One previous study found that graphic warnings including an image depicting obesity led to greater weight-related stigma.55 Thus, policymakers may choose to avoid images that could potentially be stigmatizing given that there appear to be a wide range of effective warning options. The octagon shape and square shape performed similarly, with the exception of the type 2 diabetes warning, for which the octagon shape out-performed the square shape. This builds on prior research suggesting that octagons may be slightly more effective than text but that the difference is small in magnitude.29

The impact of icon warnings (versus text-only) was stronger for parents with lower English use, suggesting that the images helped to communicate information in place of the text. Warnings on products are unlikely to appear in multiple languages due to space constraints (although laws could more feasibly require warnings on advertisements to appear in the primary language of the advertisement, as required in San Francisco’s ordinance). We observed the same pattern for parents identifying as Latino, in which the benefits of icon (versus text) warnings were larger for Latino parents than non-Latino parents. Including icons, symbols, or other images in product warnings could be an important step for increasing access to information among people with low English language use and Latino populations. It is possible that the moderation by Latino ethnicity is explained entirely by English use, although we were not able to explicitly test this due to the high correlation between these variables in our study. The magnitude of the moderation effects appear relatively small. However, even small effects could be quite meaningful when extrapolated to the full population, especially among often-repeated behaviors and since warnings would be universally applied to sugary drinks. Indeed, a recent simulation modeling study suggested that small differences in warning efficacy can lead to large differences in warnings’ impacts on health outcomes like obesity when extrapolated to the population level.44 Regardless of warning design, perceived message effectiveness ratings were higher among Latino parents and people with low English use. Future research could more deeply explore how language, acculturation, and ethnicity affect reactions to sugary drink warnings in larger samples and through qualitative work. Future studies should also continue exploring a wider range of potential moderators of warnings’ impact.

Strengths of this study include recruitment of many Latino parents and the use of a multi-stage, empirically-driven stimuli development process. Limitations include the brief exposure to the warnings online, the inability to measure the warnings’ impact on actual consumption of sugary drinks, and potentially limited power for exploratory moderation analyses. Future studies should measure behavioral outcomes (e.g., actual purchasing), the impact of warnings on other populations including children, teens, and the general population of adults, and potential unintended consequences such as weight-related stigma.55,56 Moreover, the use of a convenience sample means the generalizability of results remains to be established. However, online convenience samples tend to provide valid results for experiments.57–59

CONCLUSIONS

Our study found that multiple warning topics had beneficial effects on key predictors of behavior change. Icon and graphic warnings elicited stronger effects than text-only warnings, suggesting that including images in warnings could improve their effectiveness. Our results suggest that warnings with images may be a particularly promising tool for discouraging sugary drink consumption among Latino populations and populations with low English use. Policymakers should consider implementing sugary drink warnings as an obesity prevention policy strategy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rosalie Aguilar, MS (Salud America!), Penny Gordon-Larsen, PhD (UNC Department of Nutrition), Xavier Morales, PhD, MRP (The Praxis Project), Rebecca Puhl, PhD (Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity), Claudia Rojas, BA (UNC Center for Latino Health), and Sarah Sorscher, JD, MPH (Center for Science in the Public Interest) for their participation in the Stakeholder Advisory Board that informed the warning development.

Funding/Support:

This research was supported by grant #76290 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through its Healthy Eating Research program. General support was provided by NIH grant to the Carolina Population Center, the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) at UNC (UL1TR002489), grant numbers P2C HD050924 and T32 HD007168. K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH supported Marissa Hall’s time writing the paper. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Role of Funder/Sponsor:

The funders played no role in the study design, analysis, or presentation of results.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT04382599.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief. 2017(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-sweetened Beverage Consumption Among U.S. Youth, 2011-2014. NCHS data brief. 2017(271):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-sweetened Beverage Consumption Among U.S. Adults, 2011-2014. NCHS data brief. 2017(270): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Li Z. Trends in beverage consumption among children and adults, 2003-2014. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(2):432–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden CL, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Park S. Consumption of sugar drinks in the United States, 2005-2008. NCHS data brief. 2011(71): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han E, Powell LM. Consumption patterns of sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013; 113(1):43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(8):496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013;14(8):606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4): 1084–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010; 121(11): 1356–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poti JM, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Where are kids getting their empty calories? Stores, schools, and fast-food restaurants each played an important role in empty calorie intake among US children during 2009-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014; 114(6):908–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holsten JE, Deatrick JA, Kumanyika S, Pinto-Martin J, Compher CW. Children’s food choice process in the home environment. A qualitative descriptive study. Appetite. 2012;58(1):64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krai TV, Rauh EM. Eating behaviors of children in the context of their family environment. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(5):567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan American Health Organization. Front-of-package labeling as a policy tool for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases in the americas. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pomeranz JL, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning Policies in the Broader Legal Context: Health and Safety Warning Laws and the First Amendment. Am J Prev Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cigarette package health warnings: International status report. Ontario, Canada: Canadian Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly GE, Zatz LY, Svirsky D, John LK. The effect of graphic warnings on sugary-drink purchasing. Psychol Sci. 2018;29(8): 1321–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenblatt DH, Dixon H, Wakefield M, Bode S. Evaluating the influence of message framing and graphic imagery on perceptions of food product health warnings. Food Quality and Preference. 2019;77:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall MG, Grummon AH, Lazard AJ, Maynard OM, Taillie LS. Reactions to graphic and text health warnings for cigarettes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and alcohol: An online randomized experiment of US adults. Prev Med. 2020;137:106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics;2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajzen I The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991. ;50(2): 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Behav. 1974;2(4):328–335. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer NT, Parada H Jr, Hall MG, Boynton MH, Noar SM, Ribisl KM. Understanding why pictorial cigarette pack warnings increase quit attempts. Ann Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong M, Zhang D, Morgan JC, et al. Similarities and Differences in Tobacco Control Research Findings From Convenience and Probability Samples. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brewer NT, Jeong M, Hall MG, et al. Impact of e-cigarette health warnings on motivation to vape and smoke. Tob Control. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewer NT, Jeong M, Mendel JR, et al. Cigarette pack messages about toxic chemicals: a randomised clinical trial. Tob Control. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.City and County of San Francisco. Health Code - Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning for Advertisements. ORDINANCE N0. 100-15. 2015; https://www.sfbos.org/ftp/uploadedfiles/bdsupvrs/ordinances15/o0100-15.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- 29.Grummon AH, Hall MG, Taillie LS, Brewer NT. How should sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings be designed? A randomized experiment. Prev Med. 2019;121:158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall MG, Grummon AH, Maynard OM, Kameny MR, Jenson D, Popkin BM. Causal language in health warning labels and us adults’ perception: A randomized experiment. Am J Public Health. 2019: e1–e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baig SA, Noar SM, Gottfredson NC, Boynton MH, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. UNC Perceived Message Effectiveness: Validation of a brief scale. Ann Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baig SA, Noar SM, Gottfredson NC, Lazard AJ, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Criterion validity of message perceptions and effects perceptions in the context of anti-smoking messages. J Behav Med. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall MG, Lazard AJ, Grummon AH, Mendel JR, Taillie LS. The impact of front-of-package claims, fruit images, and health warnings on consumers’ perceptions of sugar-sweetened fruit drinks: Three randomized experiments. Prev Med. 2020; 132:105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bollard T, Maubach N, Walker N, Ni Mhurchu C. Effects of plain packaging, warning labels, and taxes on young people’s predicted sugar-sweetened beverage preferences: an experimental study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016; 13(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, Hammond D. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage health warning labels on parents’ choices. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20153185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Census Bureau. The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010; http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-Q4.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2013.

- 37.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2): 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, Ribisl KM, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Ednc Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grummon AH, Hall MG. Effectiveness of sugary drink warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. PLoS Med. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grummon AH, Taillie LS, Golden SD, Hall MG, Ranney LM, Brewer NT. Sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings and purchases: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):905–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibson 1, Brennan E, Momjian A, Shapiro-Luft D, Seitz H, Cappella JN. Assessing the consequences of implementing graphic warning labels on cigarette packs for tobacco-related health disparities. Nictoine Tob Res. 2015;17(8):898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grummon AH, Smith NR, Golden SD, Frerichs L, Taillie LS, Brewer NT. Health Warnings on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: Simulation of Impacts on Diet and Obesity Among U.S. Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ang FJL, Agrawal S, Finkelstein EA. Pilot randomized controlled trial testing the influence of front-of-pack sugar warning labels on food demand. BMC Public Health. 2019; 19(1): 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noar SM, Kelley DE, Boynton MH, et al. Identifying principles for effective messages about chemicals in cigarette smoke. Prev Med. 2018;106:31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomeranz JL, Harris JL. Children’s Fruit “Juice” Drinks and FDA Regulations: Opportunities to Increase Transparency and Support Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2020:e1–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duffy EW, Hall MG, Dillman Carpentier FR, et al. Nutrition-related claims are nearly universal on fruit drinks and are unreliable indicators of product nutritional profile. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moran AJ, Roberto CA. Health warning labels correct parents’ misperceptions about sugary drink options. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):e19–e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. California: Jossey-Bass; 2008:67–96. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noar SM, Francis DB, Bridges C, Sontag JM, Brewer NT, Ribisl KM. Effects of strengthening cigarette pack warnings on attention and message processing: A systematic review. Journal Mass Commun Q. 2017;94(2):416–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noar SM, Francis DB, Bridges C, Sontag JM, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: Systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noar SM, Rohde JA, Barker JO, Hall MG, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings increase some risk appraisals but not risk beliefs: A meta-analysis. Human Communication Research. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hall MG, Grummon AH, Lazard AJ, Maynard OM, Taillie LS. Reactions to graphic and text health warnings for cigarettes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and alcohol: An online randomized experiment of US adults. Prev Med. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayward LE, Vartanian LR. Potential unintended consequences of graphic warning labels on sugary drinks: do they promote obesity stigma? Obes Sci Pract. 2019;5(4):333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009; 17(5):941–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeong M, Zhang D, Morgan JC, et al. Similarities and differences in tobacco control research findings from convenience and probability samples. Ann Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Polit Anal. 2012;20(3):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weinberg JD, Freese J, McElhattan D. Comparing data characteristics and results of an online factorial survey between a population-based and a crowdsource-recruited sample. Sociol Sci. 2014;1:292–310. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.