Abstract

Background

In 2013, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) launched the Next Accreditation System, which required explicit documentation of trainee competence in six domains. To document narrative comments, the University of North Carolina Family Medicine Residency Program developed a mobile application to document real time observations.

Objective

The objective of this work was to assess if the Reporter, Interpreter, Manager, Expert (RIME) framework could be applied to the narrative comments in order to convey a degree of competency.

Methods

From August to December 2020, 7 individuals analyzed narrative comments of four family medicine residents. The narrative comments were collected from July to December 2019. Each individual applied the RIME framework to the comments and the team met to discuss. Comments where 5/7 individuals agreed were not further discussed. All other comments were discussed until consensus was achieved.

Results

102 unique comments were assessed. Of those comments, 25 (25.5%) met threshold for assessor agreement after independent review. Group discussion about discrepancies led to consensus about the appropriate classification for 92 (90.2%). General comments on performance were difficult to fit into the RIME framework.

Conclusions

Application of the RIME framework to narrative comments may add insight into trainee progress. Further faculty development is needed to ensure comments have discrete elements needed to apply the RIME framework and contribute to overall evaluation of competence.

Keywords: family medicine residency, mobile application, reporter-interpreter-manager-educator, qualitative research

Introduction

Competence is defined as multi-dimensional and dynamic, changing with time and linked to experience and setting. 1 The Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) defined six domains of competence expected of every resident.2,3 Programmes individually developed methods to gather assessments of trainees’ progress to guide promotion decisions.

Medical education evaluations often rely on rating scales defining trainee performance.4,5 Numerical ratings create a ranking system that can be used to benchmark trainee progress. This reductionist approach has come under scrutiny due to rating inflation 6 as well as poor correlations with narrative comments.7,8

Where competency-based performance is concerned, evaluations dependent on numerical systems fall short in capturing and evaluating progress in complex tasks and roles. 9 Questions have arisen about the validity and reliability of numeric ratings and scoring systems 2 and whether the qualities and capabilities essential for good performance post-graduation are assessable using only grades. 10 Narrative-based evaluations of clinical performance provide context to the numerical ratings. 11

With accreditation systems increasingly requiring programmes to document progress, 3 reliable systems for evaluation are needed more than ever. Entrustable professional activities (EPAs) have been advocated as a more advanced way of evaluating competence, 12 but “entrustment” still elicits confusion among clinician educators. 13 The Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator (RIME)14,15 is a developmental framework for assessing trainees in clinical settings. 14 RIME suggests trainees progress through four stages, each requiring more complex application of the skills attained at the previous level. This model offers descriptive nomenclature readily understood and accepted by trainees and preceptors. 16 Ryan and colleagues reported on reliability of the RIME framework being used as a numeric rating with medical students. 17 Narrative comments modelling this framework can provide a richness of detail of progression that numerical scales cannot. 18

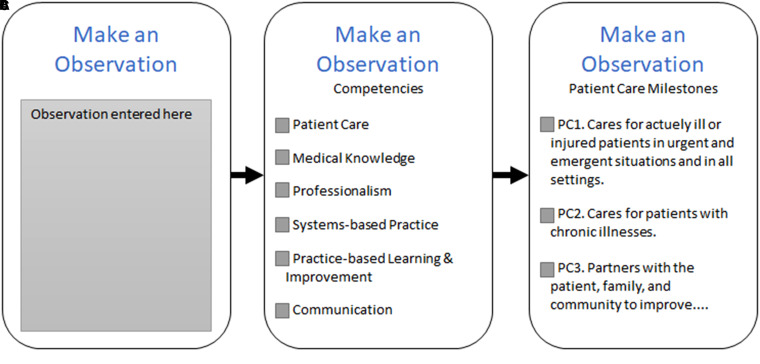

In response to the ACGME and to better document narrative-based descriptions of learners, the University of North Carolina Family Medicine Residency Program developed the Mobile Medical Milestones application (M3App©), 19 allowing faculty to document real time direct observations and provide formative feedback to residents (Figure 1). We sought to apply a process developed by Hanson et al 7 to evaluate narrative comments from the M3App© using the RIME framework to determine developmental progress from the feedback. Specific questions explored in this study were:

How accurate can independent reviewers assign RIME to narrative comments?

What challenges emerged from applying the RIME model to narrative comments?

Figure 1.

M3APP© feedback process. When completing feedback on a resident, faculty have the opportunity to enter a comment (A). They are then asked to identify a broad competency (B), followed by choosing a detailed competency (C). Therefore, multiple competencies can be selected for a single narrative comment. The figure is an adaptation of the M3APP©.

Methods

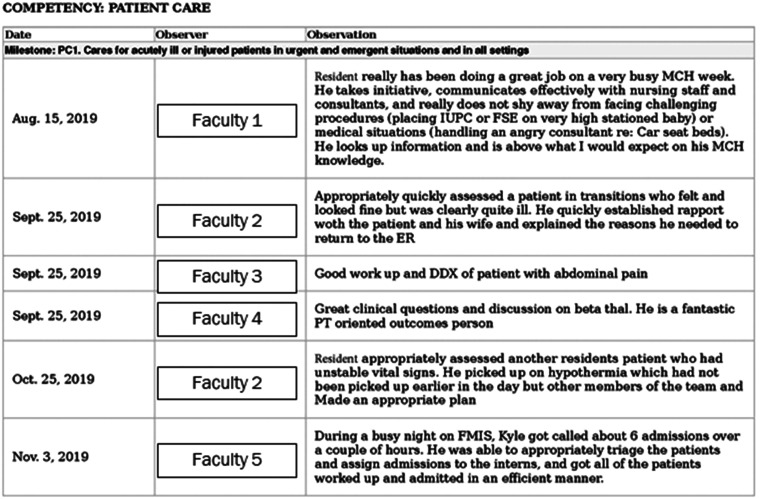

Narrative comments for four family medicine residents (2 PGY 1 and 2 PGY 2) were chosen for inclusion in this exploratory study. The narrative comments from July to December 2019 were obtained and de-identified to blind the researchers from the resident as well as evaluators (Figure 2). Because the M3App© allows preceptors to choose what ACGME Milestones the comment relates to, there were duplicate comments in the download for each resident and coded only once. This study was reviewed and approved by the university institutional review board.

Figure 2.

Example output of resident performance from the M3App©. Faculty and resident names were removed to ensure anonymity.

From August to December 2020, we analyzed narrative comments from the M3App©. Our team consisted of a medical education researcher, a family medicine physician, an internal medicine intern, and four senior medical students.

Prior to the narrative analysis, background material about the RIME framework 14 was discussed to ensure all members of the team understood each classification. Examples of comments were presented so the members of the team had a shared mental model.

All narrative comments were independently coded deductively based on the RIME framework. If it appeared comments fit more than one category, multiple RIME categories were selected. If comments were unclear or simply a compliment, they were categorized as not applicable.

The research team met to discuss individual coding results. Narrative comments where 5 of 7 codes agreed were not further discussed. All other comments were discussed until consensus was achieved.

Results

For four residents, 221 narratives were obtained. After removing duplicates, 102 unique narrative comments remained. For the first research question, rater agreement was analyzed. Only 25 (25.5%) records met our threshold for assessor agreement. Inter-rater reliability for the independent review resulted in a Cronbach's alpha = .427. After discussion, 92 (90.2%) evaluations achieved consensus among assessors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Narrative comment rater agreement.

| # of Assessors Agreeing | Independent Review Agreement | Agreement After Consensus Building |

|---|---|---|

| 7/7 | 5 | 12 |

| 6/7 | 8 | 24 |

| 5/7 | 12 | 56 |

| ≤ 4/7 | 77 | 10 |

For the second research question, reviewers debriefed about this process and the challenges faced when coding comments. Comments that were vague, using verbs such as “great” or “excellent” to describe an action without providing more specific feedback were difficult to assess and fit into the RIME framework. Examples included “Great presentation with fellows” and “from MICU, one attending called to praise his excellent care.” These items were considered more of a compliment and rated as not applicable.

Technical skills often described the particular skill undertaken in a matter-of-fact manner. For example, “…RESIDENT performed 3 excisional biopsies today. He demonstrated good technique and appropriate caution. We worked on refining his technique for buried sutures…” This made codifying a procedural skill based on RIME impossible to do.

Discussion

Narrative comments on resident performance facilitate assessment of competence. This study however demonstrated that it is difficult to assign the RIME scheme by independently reading narrative feedback, primarily because of the lack of specificity in many narratives. Pangaro and ten Cate indicated comments need to be clear to communicate progress, which many of our narratives lacked. 20

Based on our study, there remains a need for faculty development related to narrative comments.7,11 The RIME framework presents an understandable vocabulary by clinician educators. 20 Training the reviewers to write narratives with the RIME framework in mind will also help evaluators. In so doing, they may also offer suggestions of how to progress to the next level. During our consensus process, it also became evident that contextual features such as setting adds clarity to the narrative.

The authors intend to repeat this process following faculty development on writing specific, actionable feedback that includes more contextual information. Establishing a shared mental model of trainee expectations to improve feedback contributes to applying a framework like RIME, reflecting the work and skill of a physician. Additionally, a more in-depth analysis linking RIME to the competency ratings will be conducted to determine if the narrative comments are congruent.

Conclusion

Narrative comments reveal strengths and weaknesses of trainees, information that is difficult to attain from a single summative score. Applying a framework such as RIME to narrative comments can offer insights into trainee progress toward independent practice, allowing for meaningful feedback for trainees. For future steps, faculty feedback regarding input of the comments would help ensure the ability to apply the RIME framework and further determine competence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Janice Hanson from Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri for her consultation about the process of assigning the RIME framework to narrative comments. UNC School of Medicine is a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education and support for this project provided by the Reimagining Residency Initiative.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Each of the authors contributed to the conception of this project, participated in data analysis, and have been integral to writing the manuscript.

Statements and Declarations: The authors have no conflicts of interest with this work.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1.Frank JR, Snell LS, ten Cate O, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638‐645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):648‐654. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system– rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051‐1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker K. Determining resident clinical performance: getting beyond the noise. Anesthesiology. 2011 Oct;115(4):862‐878. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318229a27d. PMID: 21795965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomisato S, Venter J, Weller J, Drachman D. Evaluating the utility, reliability, and validity of a resident performance evaluation instrument. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):458‐463. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0134-7. Epub 2014 May 2. PMID: 24789481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer EG, Cozza KL, Konara RMR, Hamaoka D, West JC. Inflated clinical evaluations: a comparison of faculty-selected and mathematically calculated overall evaluations based on behaviorally anchored assessment data. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):151‐156. doi: 10.1007/s40596-018-0957-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson JL, Rosenberg AA, Lane JL. Narrative descriptions should replace grades and numerical ratings for clinical performance in medical education in the United States. Front Psychol. 2013;4:668. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman K, Hosokawa M, Donaldson J. What criteria do faculty use when rating students as potential house officers? Med Teach. 2009;31:e412‐e417. doi: 10.1080/01421590802650100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes AV, Peltier CB, Hanson JL, Lopreiato JO. Writing medical student and resident performance evaluations: beyond “performed as expected”. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):766‐768. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Squires B. Conventional grading and the delusions of academe. Educ Health. 1999;12(1):73‐77. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrasio J, Cumbler E, Trosterman A, Wald H, Brandenburg S, Aagaard E. Determining need for remediation through postrotation evaluations. J Grad Med Educ. 2012:4(1):47‐51. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00145.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor D, Park YS, Smith C, ten Cate O, Tekian A. Constructing approaches to entrustable professional activity development that deliver valid descriptions of professional practice. Teach Learn Med. 2020;33(1):89‐97. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2020.1784740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterkenburg A, Barach P, Kalkman C, Gielen M, ten Cate O. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1408‐1417. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203‐1207. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199911000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeWitt D, Carline J, Paauw D, Pangaro L. Pilot study of a 'RIME'-based tool for giving feedback in a multi-specialty longitudinal clerkship. Med Educ. 2008;42(12):1205‐1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03229.x. PMID: 19120951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sepdham D, Julka M, Hofmann L, Dobbie A. Using the RIME model for learner assessment and feedback. Fam Med. 2007;39(3):161‐163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan MS, Lee B, Richards Aet al. et al. Evaluating the reliability and validity evidence of the RIME (Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator) framework for summative assessments across clerkships. Acad Med. 2021;96(2):256‐262. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emke AR, Park YS, Srinivasan S, Tekian A. Workplace-based assessments using pediatric critical care entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):430‐438. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-01006.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page C, Reid A, Coe CLet al. et al. Piloting the Mobile Medical Milestones Application (M3App©): a multi-institution evaluation. Fam Med. 2017;49(1):35‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pangaro L, ten Cate L. Frameworks for learner assessment in medicine: AMEE Guide no. 78. Med Teach. 2013;35(6):e1197‐e1210. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.788789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]