Abstract

Antibiotic resistance among avian bacterial isolates is common and is of great concern to the poultry industry. Approximately 36% (n = 100) of avian, pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates obtained from diseased poultry exhibited multiple-antibiotic resistance to tetracycline, oxytetracycline, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and gentamicin. Clinical avian E. coli isolates were further screened for the presence of markers for class 1 integrons, the integron recombinase intI1 and the quaternary ammonium resistance gene qacEΔ1, in order to determine the contribution of integrons to the observed multiple-antibiotic resistance phenotypes. Sixty-three percent of the clinical isolates were positive for the class 1 integron markers intI1 and qacEΔ1. PCR analysis with the conserved class 1 integron primers yielded amplicons of approximately 1 kb from E. coli isolates positive for intI1 and qacEΔ1. These PCR amplicons contained the spectinomycin-streptomycin resistance gene aadA1. Further characterization of the identified integrons revealed that many were part of the transposon Tn21, a genetic element that encodes both antibiotic resistance and heavy-metal resistance to mercuric compounds. Fifty percent of the clinical isolates positive for the integron marker gene intI1 as well as for the qacEΔ1 and aadA1 cassettes also contained the mercury reductase gene merA. The correlation between the presence of the merA gene with that of the integrase and antibiotic resistance genes suggests that these integrons are located in Tn21. The presence of these elements among avian E. coli isolates of diverse genetic makeup as well as in Salmonella suggests the mobility of Tn21 among pathogens in humans as well as poultry.

Escherichia coli adversely affects avian species through infections of the blood, respiratory tract, and soft tissues. Diseases resulting from E. coli infections, such as colibacillosis, air sacculitis, and cellulitis, cause high morbidity and mortality in poultry (21), which have a significant economic impact on the poultry industry (15). These infections have traditionally been treated with antibiotics. Antibiotics once effective at controlling E. coli infections are now ineffective due to the bacterium’s acquired resistance to these compounds. Resistance in microbial pathogens like E. coli to two or more classes of antibiotics is now commonplace in both veterinary (19, 23, 26) and human (13) medicine. Although antibiotic susceptibility may return with the discontinuance of antibiotic use, antibiotic-resistant bacteria can still persist long after the removal of the selection pressure (9). Even with the rotation of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance may persist due to the genetic linkage of several antibiotic and heavy-metal resistance genes provided for their perpetuation as selection pressures change.

Multiple-drug resistance in enteric organisms like E. coli is known to be associated with integrons. Integrons generally contain an integrase gene (intI) (31, 32) and a cassette integration site (attI) (48), into which antibiotic resistance gene cassettes have integrated. A gene cassette contains an antibiotic resistance gene and a 59-bp element, a short inverted repeat element with a core recombination site (48). At least four classes of chromosomal and plasmid-borne integrons in gram-negative bacteria have been described (1, 36, 49, 51). Class 1 integrons commonly contain the quaternary ammonium compound resistance gene qacEΔ1 and the sulfonamide resistance gene sul1 in the 3′ conserved region (39, 49). The conserved 5′ and 3′ regions flank gene cassettes, which contain single or multiple antibiotic resistance gene(s). The integron acquires or exchanges antibiotic resistance genes with its specialized recombinase, intI (11, 38, 59). These genetic elements are responsible for linking antibiotic resistance genes together to form large multiple loci of antimicrobial resistance within microbial genomes (4, 45). Class 1 integrons have primarily been found on complete or truncated derivatives of the Mu-like transposon Tn402, which reside in broad-host-range plasmids (16, 41, 47, 52, 53) or within Tn21 or Tn21-like transposons (20). Tn21, a large (19.7-kb) class II replicative transposon, carries a mercury resistance (mer) operon, an integron (In2), and a transposition module (tnpA, tnpR, and res site). Variants of Tn21 included those transposons similar to Tn21 but with different or additional cassettes and/or the insertion and/or deletion of insertion sequences (IS) in regions 3′ of the inserted cassettes (29). The prototypical Tn21 carries the aadA1 gene cassette in its integron. In addition to drug resistance, Tn21 confers mercury resistance through its mercuric reductase gene, merA (30). In the case of Tn4, which does not confer mercury resistance, it appears that transposon Tn3 inserts into and disrupts the mer locus of Tn21 (29).

Resistance to specific antibiotics, like streptomycin, continues to be prevalent among avian E. coli isolates, despite the discontinuance of a given antibiotic as a therapeutic agent. The presence of integrons among clinical avian E. coli isolates may account for multiple-antibiotic resistance and continued resistance to antibiotics that have been withdrawn from use in poultry medicine. In this study, we report the high incidence of this genetic element among avian E. coli isolates and determine that the majority of these integrons are part of a Tn21-like transposon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

One hundred E. coli and eight Salmonella isolates were obtained from the tracheas, lungs, air sacs, livers, and spleens of chickens, quail, ostriches, and turkeys. Clinical avian E. coli and Salmonella isolates were stored as 20% glycerol stocks at −80°C.

Colony blots.

DNA probes for Southern analysis were generated by PCR with primers specific for int, aadA1, qacEΔ1, and merA. E. coli SK1592(pDU202) (57) that contains Tn21 served as the template for generating PCR-based DNA probes for DNA-DNA hybridizations. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Molecular Genetics Instrumentation Facility at the University of Georgia, Athens (Table 1). The total DNA template for PCR was prepared as follows. A 1.5-ml overnight culture was centrifuged to pellet the bacteria, resuspended to its original volume in distilled H2O, and boiled for 10 min. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant was diluted 10-fold in distilled H2O to serve as a template for PCR. The DNA template was stored at −20°C. One hundred nanograms of E. coli chromosomal DNA served as a template in a 10-μl PCR mixture. This reaction mixture consisted of 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1× PCR buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4]), bovine serum albumin (0.25 mg/ml), 50 pmol (each) of forward and reverse PCR primers, and 0.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). The program parameters for the Idaho Technology Rapidcycler (Idaho Falls, Idaho) (58) were (i) 94°C for 0 s, (ii) 55°C for 0 s, and (iii) 72°C for 15 s for 30 cycles. DNA products from PCR were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. DNA was separated on a 1.5% agarose–1× Tris-acetate-EDTA gel at 70 V. The 100-bp ladder (Promega, Madison, Wis.) served as the molecular weight (MW) standard for determining the MW of the PCR products. The DNA fragment corresponding in size to the MW expected for specific primer pairs was extracted from the agarose gel slice with a Supelco GelElute agarose spin column (Bellefonte, Pa.). The procedure for DNA-DNA hybridizations was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (44) with hybridizations and washes done at 68°C. Hybridizing DNA fragments were detected with digoxigenin antibody-alkaline phosphatase conjugate provided with the Genius system (Boehringer Mannheim).

TABLE 1.

PCR primersa

| Gene | PCR primers | Expected size of PCR product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ CS | GGCATCCAAGCAGCAAG | 28 | |

| 3′ CS | AAGCAGACTTGACCTGA | 28 | |

| intI1 | F: CCTCCCGCACGATGATC | 280 | 28 |

| R: TCCACGCATCGTCAGGC | |||

| qacEΔ1 | F: AAGTAATCGCAACATCCG | 250 | This study |

| R: AAAGGCAGCAATTATGAG | |||

| merA | F: ACCATCGGCGGCACCTGCGT | 1,232 | 30 |

| R: ACCATCGTCAGGTAGGGGAACA |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Southern hybridization.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from avian E. coli (44) and digested with EcoRI. The DNA was separated on a 1% agarose–1× Tris-acetate-EDTA gel and ethidium bromide (5 μg/ml) and transferred to a nylon membrane (44). Single-stranded DNA was cross-linked to membranes with ultraviolet light (optimal cross-linking setting; Fisherbiotech UV Crosslinker). Membranes were hybridized with DNA probes specific for aadA or merA. DNA probes were prepared as outlined above. Procedures for DNA-DNA hybridizations and detection were performed as specified in the protocol for the Genius 3 kit (Boehringer Mannheim). The annealing temperature for hybridizations and washes was 68°C (44).

Mercury resistance assay.

Bacterial isolates were streaked onto tryptone broth agar plates, containing 1.0 × 10−4 M mercuric chloride, and Luria-Bertani plates (50). Growth of isolated, single colonies on the mercuric chloride plates indicated the presence of the mercury resistance phenotype.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Antibiotic resistance patterns in avian E. coli.

One hundred clinical avian E. coli isolates were examined for their general susceptibility to a battery of antibiotics of human and veterinary significance. The prevalence of resistance to the aminoglycosides ranged from 27% for kanamycin to 97% for streptomycin among these isolates (Table 2). Most E. coli isolates (86%) were resistant to the tetracyclines, tetracycline and oxytetracycline. Avian E. coli isolates were generally resistant to both streptomyocin and the sulfonamides (97 of 100). A high percentage of the E. coli strains isolated were also resistant to ampicillin (30%) and chloramphenicol (10%). Similar observations have been reported, in other countries, for coliforms isolated from avian species (3, 7, 54, 55). It is difficult to determine, however, whether the higher incidence of antibiotic resistance corresponds to the continued use of ampicillin and chloramphenicol in these countries. Neither antibiotic is currently recommended as a therapeutic agent in avian medicine, although ampicillin resistance may be a reflection of cross-resistance to ceftiofur, a third-generation cephalosporin currently available as a therapeutic for poultry (17). On the other hand, chloramphenicol has been banned from use in food animals since the 1980s in the United States and Canada (18). The majority (64%) of clinical E. coli strains isolated from diseased birds at the Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center, University of Georgia, exhibited multiple resistance to five or more antibiotics (Table 3). The common multiple-antibiotic resistance profile among these isolates includes resistance to oxytetracycline, tetracycline, gentamicin, streptomycin, and sulfonamide. Gentamicin resistance may be due to the inclusion of this antibiotic with the Marek’s vaccine that is administered to almost all poultry in ovo (14, 42). Since class 1 integrons typically assemble arrays of antibiotic resistance genes, it was logical to determine the integron incidence among avian clinical isolates.

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of avian E. coli

| Class and antibiotic | No. of resistant strains (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| β-Lactams | |

| Ampicillin | 30a |

| Chloramphenicols | |

| Chloramphenicol | 11 |

| Tetracyclines | |

| Tetracycline | 1 |

| Oxytetracycline | 5 |

| Tetracycline and oxytetracycline | 86 |

| Aminoglycosides | |

| Streptomycin | 97 |

| Gentamicin | 65 |

| Neomycin | 30 |

| Kanamycin | 27 |

β-lactamase positive.

TABLE 3.

Antibiotic resistance patterns of avian E. coli strains

| Antibiotic resistancea | No. of resistant strains (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Ap Cm Tc Au Gm S Su | 3 |

| Ap Tc Au Gm S Su | 9 |

| Tc Au S Su | 6 |

| Tc Au Gm S Su | 36 |

| Tc Au Km Gm Ne S Su | 8 |

| Tc Au Gm Ne S Su | 8 |

| Drug resistance to ≥5 antibiotics | 64 |

| S-Su-resistant E. coli strains with class 1 integron gene, intI1 | 84b |

The most common pattern of multiple-drug resistance among strains of E. coli isolated from poultry is shown in line 4 of the table (boldface type). Ap, ampicillin; Au, oxytetracycline; Cm, chloramphenicol; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Ne, netilmicin; S, streptomycin; Su, sulfonamide.

No. of strains tested, 97 (87% resistant).

The incidence of genes associated with integrons among avian E. coli.

One hundred avian E. coli isolates were screened for the presence of intI1 and qacEΔ1, markers for class 1 integrons (32, 39). Sixty-three clinical isolates were positive for both intI1 and qacEΔ1 (Table 4). However, 27 avian E. coli isolates did not possess either marker (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Distribution of class 1 integrons and the mercury resistance gene merA among clinical avian E. coli isolates

| Genotype | No. positive (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| intI1 aadA1 qacΔE1 merA | 50 |

| intI1 aadA1 qacΔE1 | 13 |

| intI1 aadA1 merA | 4 |

| aadA1 qacΔE1 merA | 1 |

| intI1 aadA1 | 0 |

| intI1 merA | 1 |

| merA | 3 |

| aadA1 | 1 |

| No class 1 integron or mer genes | 27 |

Integron-mediated, antibiotic resistance genes are common among clinical Enterobacteriaceae associated with disease in humans (33, 43). Globally disseminated Tn21-like transposons which carry class 1 integrons, as well as close relatives of In2 which are found in other independent locations (typically conjugative plasmids) (5, 29), account for the high incidence of this element among commensal (57), environmental (12), and clinical (62) bacterial isolates. To further characterize the integrons of avian E. coli, PCR was used to amplify and sequence the gene cassettes associated with the identified class 1 integrons (27, 28). With previously published class 1 integron PCR primers (28), several avian E. coli isolates that were positive for intI1 and qacEΔ1 yielded amplicons of approximately 1.0 kb each (data not shown). The DNA sequences of the PCR amplicons were nearly identical to the nucleotide sequence for the aadA1 gene, which encodes streptomycin and spectinomycin resistance. There was 99% identity between the PCR amplicon’s DNA sequence and aadA1 genes from E. coli (25), Shigella flexneri (10), Klebsiella spp. (40, 52), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (GenBank accession no. L36547). The class 1 integrons examined did not possess the complete resistance phenotype observed among the clinical avian E. coli isolates. This does not rule out the existence of other class 1 integrons in avian E. coli strains that we may not have been able to detect.

A large percentage of E. coli isolates with streptomycin and sulfonamide resistance were also positive for the class 1 integrase gene intI1 (84 of 97) (Table 3). Since the antibiotic resistance gene aadA1 was present in several avian E. coli isolates, we assessed its distribution among the clinical E. coli isolates by DNA hybridization. All E. coli isolates positive for intI1 and qacEΔ1 (n = 63) also had the aadA1 resistance gene (Table 4). These same genetic markers were also evident in 6 of 8 avian Salmonella isolates examined (data not shown). In assessing the distribution of class 1 integron markers and merA among avian E. coli isolates, we also noted other genotypes where intI1, qacEΔ1, aadA1, or merA genes were absent. These unusual genotypes (intI1 aadA1 merA, aadA1 qacΔE1 merA, intI1 merA, and aadA1) might represent recombinational events that occur in class 1 integrons and the mer operon (29).

The integrons of avian E. coli are part of the mercury resistance transposon Tn21.

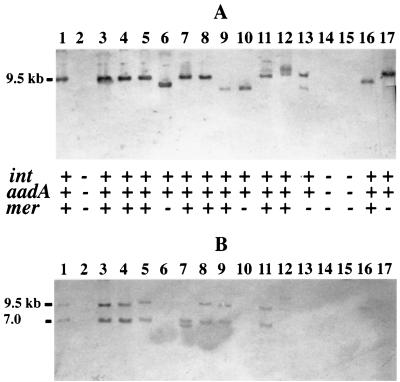

Since the aadA1 gene was associated with all E. coli isolates positive for intI1 and qacEΔ1 and since this gene has been associated with the mercury resistance transposon Tn21 (22), we looked into the possibility that the integrons in avian E. coli are actually part of a Tn21-like transposon. We initially examined the occurrence of the Tn21 mercury reductase gene merA among these isolates. Fifty avian E. coli strains were positive for two known Tn21 markers, aadA1 and merA. The mercury resistance gene merA was present in 79% of E. coli isolates that were also positive for intI1, qacEΔ1, and aadA1 genes. The phenotypes associated with Tn21, mercury resistance and streptomycin resistance, were also present in several group B and E Salmonella isolates (5 of 8) examined. Among the E. coli isolates that were positive for merA, 86% were resistant to mercuric chloride. To demonstrate that the genes conferring these phenotypes, mercury resistance and streptomycin resistance, are part of a Tn21-like transposon in these isolates, the linkage between aadA1 and merA was determined by Southern analysis. Plasmid DNA was isolated from 14 avian E. coli strains positive for aadA1 and merA, digested with the EcoRI restriction enzyme, and probed with either the aadA1 or merA probe. The merA probe hybridized to two DNA fragments of 9.5 and 7 kb in 7 of 10 avian E. coli isolates positive for mer as expected, since EcoRI cuts in the center of most merA genes (Fig. 1B). The second DNA probe for aadA1 hybridized to a single DNA fragment of 9.5 kb in 7 of 10 avian E. coli isolates positive for intI1, aadA, and merA. merA and aadA1 (Fig. 1A) are most likely linked, since both DNA probes recognized the same 9.5-kb EcoRI DNA fragment in several of the isolates examined (Fig. 1, lanes 1, 3 to 5, 8, 11, and 12). This evidence lends support to the idea that the incidence of these genes among avian E. coli strains is due to the presence of a Tn21-like element. However, these avian E. coli isolates do not contain the canonical Tn21 but a derivative. According to the genetic map of Tn21, aadA and merA sequences are expected to map to a 13-kb EcoRI DNA fragment (GenBank accession no. AF071413) (29), not the 9.5-kb EcoRI DNA fragment observed in avian E. coli strains positive for intI1, aadA1, and merA. The smaller 9.5-kb EcoRI DNA fragment suggests a probable deletion of the IS1326 and IS1353 sequences of canonical Tn21 (5, 29) to generate these Tn21-like elements. An additional EcoRI restriction enzyme site, present in tniBΔ1 of the canonical Tn21 (29), is also absent from these Tn21-like sequences in avian E. coli.

FIG. 1.

The physical linkage between the integron-associated drug resistance genes aadA1 and merA of Tn21 in avian E. coli. The plasmid DNA, cut with restriction enzyme EcoRI, was probed for aadA1 (A) or merA (B). Avian E. coli strains examined in this study were positive (+) by colony blots for intI1, aadA1, merA (lanes 3 to 5, 7 to 9, 11 to 12, and 16), int, and aadA (lanes 6, 10, 13, and 17) or negative (−) for all class I integron genes and merA of Tn21 (lanes 14 and 15). E. coli K-12 with pDU202 served as the positive control (lane 1), while the same E. coli K-12 strain without this plasmid served as the negative control (lane 2). Both DNA probes recognized a 9.5-kb DNA fragment (lanes 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, and 12), demonstrating the physical linkage of aadA1 and merA.

This study is the first to document the dissemination of Tn21 among an important group of pathogenic avian E. coli isolates. The dissemination of mercury resistance in avian E. coli appears to be due to Tn21. This element has also been reported in gram-negative clinical isolates associated with illness in humans (62). Resistance to the heavy metal, mercury, is not unprecedented among E. coli strains of veterinary significance. Mercury resistance among avian E. coli isolates (7), as well as in the pathogenic E. coli that is associated with disease in other domestic animals (23), has previously been reported, although the genetic determinant responsible for resistance has never been identified. It is currently uncertain what selective advantage the organism may gain from mercury resistance, since mercuric compounds are not used in hatchery disinfectants. One possible source may be the fish meal present in poultry feed, since fish can accumulate toxic compounds, including mercury (6). The use of fish meal in chicken feed varies according to region, availability, and market price (16a). Since MerA mercury reductase does not confer cross-resistance to other heavy metals (46), the selection pressure is probably not due to the arsenic compounds that are added to feed as coccidiostats (37). There is presumably an as yet-unidentified selection pressure that favors Tn21’s widespread dissemination among poultry pathogens, since this transposon was also identified among Salmonella strains isolated from poultry (data not shown).

The widespread distribution of the transposon Tn21 among clinical isolates is possibly attributable to the conjugative plasmids on which they reside. Many of these avian E. coli isolates contain ColV plasmids (60, 61), which may give the bacterial host a selective advantage in its competition with normal flora (8). This transposable element may also be carried by a virulence plasmid, which might explain the dissemination and persistence of Tn21 in avian E. coli. Previous examples of physical linkages between antibiotic resistance and heavy-metal resistance and virulence factors on conjugative plasmids in E. coli have been described (24, 35). We are currently looking at other factors linked to the same plasmid(s) associated with Tn21, which may explain the continued propagation of this element without obvious selection pressure.

Currently the only antibiotics approved for poultry use and proven effective at combating infection are two fluoroquinolones, enrofloxacin and sarafloxacin. Effectiveness of these drugs may be short lived, as E. coli is becoming resistant to quinolones and fluoroquinolones (2, 3, 55, 56). In addition to continuing development of new antimicrobial agents, another key to solving the problem of multiple-antibiotic resistance may be identifying and exploiting conditions unfavorable to the persistence and dissemination of integrons in the bacterial cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in J.J.M.’s lab is supported by the State of Georgia’s Veterinary Medicine Agriculture Research Grant (AV50 34-26-GR537-000) and USDA formula funds (97-435). An NSF Research Training Grant in Prokaryotic Diversity (BIR-9413235) supported L.B. Work in A.O.S.’s lab is supported by the Wallace Research Foundation, the International Academy of Oral Medicine and Toxicology, and NIH grant GM28211.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa Y, Murakami M, Suzuki K, Ito H, Wacharotayankun R, Ohsuka S, Kato N, Ohta M. A novel integron-like element carrying the metallo B-lactamase gene blaIMP. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1612–1615. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazile-Pham-Khac S, Truong Q C, LaFont J, Gutmann L, Zhou X Y, Osman M, Moreau N J. Resistance of fluoroquinolones in Escherichia coli isolated from poultry. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1504–1507. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco J E, Blanco M, Mora A, Blanco J. Prevalence of bacterial resistance to quinolones and other antimicrobials among avian Escherichia coli strains isolated from septicemic and healthy chickens in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2184–2185. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2184-2185.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs C E, Fratamico P M. Molecular characterization of an antibiotic resistance gene cluster of Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:846–849. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown H J, Stokes H W, Hall R M. The integrons In0, In2, and In5 are defective transposon derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4429–4437. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4429-4437.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camusso M, Vigano L, Balestrini R. Bioconcentration of trace metals in rainbow trout: a field study. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1995;31:133–141. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1995.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caudry S D, Stanisich V A. Incidence of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli associated with frozen chicken carcasses and characterization of conjugative R plasmids derived from such strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:701–709. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao L, Levin B R. Structured habitats and the evolution of anticompetitor toxins in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6324–6328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaslus-Dancla E, Gerbaud G, LaGorce M, LaFont J, Courvalin P. Persistence of an antibiotic resistance plasmid in intestinal Escherichia coli of chickens in the absence of selective pressure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:784–788. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.5.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinault A C, Blakesley V A, Roessler E, Willis D G, Smith C A, Cook R G, Fenwick R G., Jr Characterization of transferable plasmids from Shigella flexneri 2a that confer resistance to trimethoprim, streptomycin, and sulfonamides. Plasmid. 1986;15:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(86)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collis C M, Hall R M. Site-specific deletion and rearrangement of integron insert genes catalyzed by the integron DNA integrase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1574–1585. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1574-1585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlberg C, Hermansson M. Abundance of Tn3, Tn21, and Tn501 transposase (tnpA) sequences in bacterial community DNA from marine environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3051–3056. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3051-3056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennesen P J, Bonten M J, Weinstein R A. Multiresistant bacteria as a hospital epidemic problem. Ann Med. 1998;30:176–185. doi: 10.3109/07853899808999401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edison C S, Kleven S H. Vaccination of chickens against Marek’s disease with the turkey herpesvirus vaccine using a pneumatic vaccinator. Poult Sci. 1976;55:960–969. doi: 10.3382/ps.0550960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elfadil A A, Vaillancourt J P, Meek A H, Julian R J, Gyles C L. Description of cellulitis lesions and associations between cellulitis and other categories of condemnation. Avian Dis. 1996;40:690–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falbo V, Carattoli A, Tosini F, Pezzella C, Dionisi A M, Luzzi I. Antibiotic resistance conferred by a conjugative plasmid and a class I integron in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor strains isolated in Albania and Italy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:693–696. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Feedstuffs. Ingredient market. Feedstuffs. 1999;71:32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Drug Administration. 1999. Greenbook: on-line database system on FDA approved animal drug products. [Online.] http://www.fda.gov/cvm/fda/greenbook. [4 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 18.Gilmore A. Chloramphenicol and the politics of health. Can Med Assoc J. 1986;134:423–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez E A, Blanco J. Serotypes and antibiotic resistance of verotoxigenic (VTEC) and necrotizing (NTEC) Escherichia coli strains isolated from calves with diarrhoea. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;51:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grinsted J, de la Cruz F, Schmitt R. The Tn21 subgroup of bacterial transposable elements. Plasmid. 1990;24:163–189. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90001-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross W B. Colibacillosis. In: Calnek B W, editor. Diseases of poultry. 9th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1991. p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall R M, Vockler C. The region of the IncN plasmid R46 coding for resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, streptomycin/spectinomycin and sulphonamides is closely related to antibiotic resistance segments found in IncW plasmids and in Tn21-like transposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7491–7501. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.18.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harnett N M, Gyles C L. Resistance to drugs and heavy metals, colicin production, and biochemical characteristics of selected bovine and porcine Escherichia coli strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:930–935. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.5.930-935.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harnett N M, Gyles C L. Linkage of genes for heat-stable enterotoxins, drug resistance, K99 antigen, and colicin in bovine and porcine strains of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollingshead S, Vapnek D. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a gene encoding a streptomycin/spectinomycin adenylyltransferase. Plasmid. 1985;13:17–30. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irwin R J, McEwen S A, Clarke R C, Meek A H. The prevalence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli and antimicrobial resistance patterns of nonverocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli and Salmonella in Ontario broiler chickens. Can J Vet Res. 1989;53:411–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lévesque C, Piché L, Larose C, Roy P H. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:185–191. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lévesque C, Roy P H. PCR analysis of integrons. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 590–594. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebert C A, Hall R M, Summers A O. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:507–522. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.507-522.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liebert C A, Wireman J, Smith T, Summers A O. Phylogeny of mercury resistance (mer) operons of gram-negative bacteria isolated from the fecal flora of primates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1066–1076. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1066-1076.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez E, de la Cruz F. Transposon Tn21 encodes a RecA-independent site-specific integration system. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;211:320–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00330610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez E, de la Cruz F. Genetic elements involved in Tn21 site-specific integration, a novel mechanism for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. EMBO J. 1990;9:1275–1278. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez-Freijo P, Fluit A C, Schmitz F-J, Grek V S C, Verhoef J, Jones M E. Class I integrons in Gram-negative isolates from different European hospitals and association with decreased susceptibility to multiple antibiotic compounds. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:689–696. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurer J J, Lee M D, Lobsinger C, Brown T P, Maier M, Thayer S. Molecular typing of avian Escherichia coli isolates by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Avian Dis. 1998;42:431–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazaitis A J, Maas R, Maas W K. Structure of a naturally occurring plasmid with genes for enterotoxin production and drug resistance. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:97–105. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.97-105.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazel D, Dychinco B, Webb V A, Davies J. A distinctive class of integron in the Vibrio cholerae genome. Science. 1998;280:605–608. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDougald L R, Keshavarz K, Rosenstein M. Anticoccidial efficacy of salinomycin (AHR-3096C) and compatibility with roxarsone in floor-pen experiments with broilers. Poult Sci. 1981;60:2416–2422. doi: 10.3382/ps.0602416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nucken E J, Henschke R B, Schmidt F R. Site-specific integration of genes into hot spots for recombination flanking aadA in Tn21 transposons. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:137–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00264222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulson I T, Littlejohn T G, Rådström P, Sundström L, Sköld O, Swedberg G, Skurray R A. The 3′ conserved segment of integrons contains a gene associated with multidrug resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:761–768. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preston K E, Kacica M A, Limberger R J, Archinal W A, Venezia R A. The resistance and integrase genes of pACM1, a conjugative multiple-resistance plasmid, from Klebsiella oxytoca. Plasmid. 1997;37:105–118. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rådström P, Sköld O, Swedberg G, Flensburg J, Roy P H, Sundström L. Transposon Tn5090 of plasmid R751, which carries an integron, is related to Tn7, Mu, and the retroelements. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3257–3268. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3257-3268.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricks C A, Avakian A, Bryan T, Gildersleeve R, Haddad E, Ilich R, King S, Murray L, Phelps P, Poston R, Whitfill C, Williams C. In ovo vaccination technology. Adv Vet Med. 1999;41:495–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sallen B, Rajoharison A, Desvarenne S, Mabilat C. Molecular epidemiology of integron-associated antibiotic resistance genes in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:195–202. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandvang D, Aarestrup F M, Jensen L B. Characterization of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:177–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schottel J, Mandal A, Clark D, Silver S, Hedges R W. Volatilisation of mercury and organomercurials determined by inducible R- factor systems in enteric bacteria. Nature. 1974;251:335–337. doi: 10.1038/251335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro J A, Sporn P. Tn402: a new transposable element determining trimethoprim resistance that inserts in bacteriophage lambda. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:1632–1635. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.3.1632-1635.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stokes H W, O’Gorman D B, Recchia G D, Parsekhian M, Hall R M. Structure and function of 59-base element recombination sites associated with mobile gene cassettes. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:731–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6091980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stokes H W, Hall R M. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1669–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Summers A O, Wireman J, Vimy M J, Lorscheider F L, Marshall B, Levy S B, Bennet S, Billard L. Mercury released from dental “silver” fillings provokes an increase in mercury- and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in oral and intestinal floras of primates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:825–834. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundstrom L, Radstrom P, Swedberg G, Skold O. Site-specific recombination promotes linkage between trimethoprim- and sulfonamide resistance genes. Sequence characterization of the dhfrV and sul1 and a recombination active locus of Tn21. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;213:191–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00339581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tolmasky M E. Sequencing and expression of aadA, bla, and tnpR from the multiresistance transposon Tn1331. Plasmid. 1990;24:218–226. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tosini, F., P. Visca, I. Luzzi, A. M. Dionisi, C. Pezzella, A. Petrucca, and A. Carattoli. Class 1 integron-borne multiple-antibiotic resistance carried by IncFI and IncL/M plasmids in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3053–3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Tsubokura M, Matsumoto A, Otsuki K, Animas S B, Sanekata T. Drug resistance and conjugative R plasmids in Escherichia coli strains isolated from migratory waterfowl. J Wildl Dis. 1995;31:352–357. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-31.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turtura G C, Massa S, Ghazvinizadeh H. Antibiotic resistance among coliform bacteria isolated from carcasses of commercially slaughtered chickens. Int J Food Microbiol. 1990;11:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(90)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White D G, Piddock L J V, Maurer J. Abstracts of the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Emergence of multiple fluoroquinolone resistance among avian Escherichia coli in north Georgia, abstr. V-127; p. 534. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wireman J, Liebert C A, Smith T, Summers A O. Association of mercury resistance with antibiotic resistance in the gram-negative fecal bacteria of primates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4494–4503. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4494-4503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wittwer C T, Fillmore G C, Hillyard D R. Automated polymerase chain reaction capillary tubes with hot air. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4353–4357. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.11.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wohllenben W, Arnold W, Bissonette L, Palletier A, Tanguay A, Roy P H, Gamboa G C, Barry G F, Aubert E, Davies J, Kagan S A. On the evolution of Tn21-like multiresistance transposons: sequence analysis of the gene (aacC1) for gentamicin acetyltransferase-3-I(AAC(3)-I), another member of the Tn21-based expression cassette. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02464882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wooley R E, Nolan L K, Brown J, Gibbs P S, Giddings C W, Turner K S. Association of K-1 capsule, smooth lipopolysaccharides, traT gene, and colicin V production with complement resistance and virulence of avian Escherichia coli. Avian Dis. 1993;37:1092–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wooley R E, Spears K R, Brown J, Nolan L K, Dekich M A. Characteristics of conjugative R-plasmids from pathogenic avian Escherichia coli. Avian Dis. 1992;36:348–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuhlsdorf M T, Wiedmann B. Tn21-specific structures in gram-negative bacteria from clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1915–1921. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]