Abstract

If variation in azole resistance is due to inherent differences in strains of Candida albicans, as a predominantly clonal organism, then correlation between multilocus genotypes and drug resistance would be expected. A sample of 81 clinical isolates from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Toronto, Canada, plus 3 reference isolates were genotyped at 16 loci, distributed on all linkage groups, by means of oligonucleotide hybridizations specific for each of the alleles at each locus. These multilocus genotypes were significantly correlated with DNA fingerprints obtained with the species-specific probe 27A, indicating widespread linkage disequilibrium in the genome. There were 64 multilocus diploid genotypes and 77 DNA fingerprint types delineated in this sample. Neither the multilocus genotyping nor DNA fingerprinting alone identified all of the 81 types identified by the combination of these two methods. Multilocus genotypes were not predictive of fluconazole resistance, suggesting that resistance is gained or lost too quickly to be predicted by linkage with neutral markers.

The deployment of antimicrobial agents in medicine and agriculture is nearly always followed by the evolution of resistance to these agents in the pathogen (23). In fungal pathogens, the dramatic increase in the incidence of opportunistic infections in recent years has been accompanied by an equally dramatic increase in resistance by the pathogen to the limited number of antifungal drugs available. For example, the yeast Candida albicans and related species cause serious illness in immunocompromised patients, such as those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although the introduction of azole drugs, especially fluconazole, has greatly facilitated the treatment of infections caused by Candida, the emergence of resistance in this yeast may have severely reduced the effectiveness of azoles (12, 16, 26).

Our interest is in the evolutionary mechanisms of emergence and spread of resistance to antifungal agents in the pathogenic yeast C. albicans. In this study, we compared resistance to the azole drugs fluconazole, ketoconazole, and itraconazole with multilocus genotypes based on nucleotide site polymorphisms in a sample of 89 isolates of Candida from oral mucosa in a group of HIV-infected patients in Toronto, Canada. Linkage disequilibrium among neutral genetic markers in C. albicans is well documented (5, 15, 24, 25), even where there is no genetic differentiation among geographically diverse samples of C. albicans (10, 28, 29). Because of the linkage disequilibrium, indicative of a primarily clonal system, we reasoned that variation in multilocus genotypes based on neutral polymorphisms should be positively correlated with variation in drug resistance, but only if the resistance phenotype is stable enough for such an association to exist. In the actual comparison, we found that variation among multilocus genotypes was not predictive of variation in the level of fluconazole resistance. This suggests that fluconazole resistance in populations is labile; resistance is either gained or lost too quickly to be predicted by linkage with neutral markers in this population sample.

In order to compare azole resistance and multilocus genotypes, we developed a new genotyping system based on an assay of nucleotide polymorphisms distributed on all chromosomes. Several methods for genotyping strains of C. albicans have been used to describe populations of this fungus (reviewed by Pujol et al. [14]). Our method uses allele-specific oligonucleotide probes in Southern hybridizations with PCR-amplified DNA regions. The system clearly distinguishes heterozygotes from homozygotes at each polymorphic site, resulting in an unambiguous multilocus genotype for each isolate tested. In the process of genotyping, we also found eight highly atypical isolates, seven of which were later identified as C. dubliniensis and one of which was identified as C. tropicalis; the remaining sample consisted of 81 clinical isolates of C. albicans.

To test the discriminatory power of the genotyping system, DNA fingerprints were obtained with the commonly used species-specific probe 27A. There are approximately 10 copies of the 27A sequence dispersed throughout the genome. DNA polymorphisms are produced at high rates, largely due to internal changes in members of this gene family (22). These polymorphisms have been widely used in studies of C. albicans. The number of allelic differences among multilocus genotypes was positively correlated with the number of differences in the hybridizing fragments present in DNA fingerprints; this indicated widespread linkage disequilibrium in this population of C. albicans and validated our rationale for comparing genotypes and drug resistance.

The objective of this population-genetic study was to determine if azole resistance can be predicted by multilocus genotype in a sample of C. albicans isolates from HIV-infected patients. This was done by comparing two DNA typing methods and examining the relationship between DNA typing markers and azole resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains of Candida.

Of the 89 isolates initially identified as C. albicans obtained from oral swabs from HIV-infected patients (Table 1), 22 isolates were from patients attending the Immunodeficiency Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children (HSC) and 67 isolates were from patients attending the Toronto Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. We selected this geographically restricted sample because the patients from which this sample was obtained are more likely to be infected by the same pool of strains of this fungus jointly sharing in the processes of genetic drift and selection than would patients from different locations.

TABLE 1.

Azole resistance levels

| Type of isolates (no.) | Isolatea | MIC (μg/ml) (character)b of:

|

Type of isolates (no.) | Isolatea | MIC (μg/ml) (character)b of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | Ketoconazole | Itraconazole | Fluconazole | Ketoconazole | Itraconazole | |||||

| Clinical C. albicans (81) | P1 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | ||||||

| P11 | 0.125 (0) | <0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P15 | 0.125 (0) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P21 | 0.125 (0) | <0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P22 | 0.125 (0) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P23 | 0.125 (0) | 0.06 (1) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P24 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P26 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P27a | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P29 | 0.25 (1) | 0.06 (1) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P30 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P33a | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P37 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| P39 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.06 (2) | |||||||

| T1 | 32 (8) | 1 (5) | 0.25 (4) | |||||||

| T3 | 8 (6) | 1 (5) | 0.5 (5) | |||||||

| T4 | 64 (9) | 1 (5) | 0.25 (4) | |||||||

| T5 | 64 (9) | 0.5 (4) | 0.25 (4) | |||||||

| T15 | 0.25 (1) | 0.06 (1) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T16 | 1 (3) | 0.125 (2) | 0.03 (1) | |||||||

| T17b | 1 (3) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (3) | |||||||

| T18 | 1 (3) | 0.06 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |||||||

| T19 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T22 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T23 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T24 | 2 (4) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | |||||||

| T25c | 32 (8) | 0.125 (2) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T26 | 0.5 (2) | 0.06 (1) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T28 | 8 (6) | 16 (9) | >8 (9) | |||||||

| T29 | 1 (3) | <0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T30c | 16 (7) | 0.125 (2) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T32 | 0.5 (2) | 0.06 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |||||||

| T36 | 32 (8) | 0.5 (4) | 0.25 (4) | |||||||

| T37 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T38 | 2 (4) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (3) | |||||||

| T39c | 32 (8) | 0.125 (2) | 0.03 (1) | |||||||

| T42d | 64 (9) | 16 (9) | 8 (9) | |||||||

| T45 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | <0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T46d | 64 (9) | 0.25 (3) | 0.125 (3) | |||||||

| T50e | 8 (6) | 0.125 (2) | 0.06 (2) | |||||||

| T52f | 1 (3) | 0.125 (2) | 0.015 (0) | |||||||

| T56e | 8 (6) | 0.06 (1) | 0.06 (2) | |||||||

| T62 | 0.5 (2) | 0.125 (2) | 0.03 (1) | |||||||

| T63g | 64 (9) | 0.125 (2) | 0.06 (2) | |||||||

| T64b | 4 (5) | 0.06 (1) | 0.125 (3) | |||||||

| T65g | 16 (7) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (3) | |||||||

| T66b | 4 (5) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (3) | |

| T68g | 32 (8) | 0.25 (3) | 0.25 (4) | |

| T73 | 0.5 (2) | 0.125 (2) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T77 | 8 (6) | 0.25 (3) | 0.125 (3) | |

| T82 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T84 | 0.5 (2) | 0.06 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T86 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T87 | 8 (6) | 0.5 (4) | 0.125 (3) | |

| T96 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T98 | 32 (8) | 0.5 (4) | 0.25 (4) | |

| T99 | 8 (6) | 0.06 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T100 | 32 (8) | 0.5 (4) | 0.25 (4) | |

| T101h | 32 (8) | 0.5 (4) | 0.5 (5) | |

| T103 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T104i | 16 (7) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (3) | |

| T105i | 16 (7) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (3) | |

| T107h | 32 (8) | 0.25 (3) | 8 (9) | |

| T109 | 0.25 (1) | 0.06 (1) | >8 (9) | |

| T112 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T115 | 16 (7) | 0.25 (3) | 0.06 (2) | |

| T116h | 32 (8) | 0.5 (4) | 0.25 (4) | |

| T117f | 2 (4) | 16 (9) | >8 (9) | |

| T118 | 0.25 (1) | 0.06 (1) | 0.06 (2) | |

| T119 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T120 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T121 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T122 | 0.5 (2) | 0.06 (1) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T124 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T125 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T126 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T128 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T130 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T131j | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | 0.06 (2) | |

| T132 | 0.5 (2) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| T135f | 1 (3) | 0.03 (0) | 0.015 (0) | |

| Reference C. albicans (3) | CA | 1 (3) | ||

| CAI4 | 0.25 (1) | |||

| WO-1 | 1 (3) | |||

| Atypical Candida (8) | T10 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | <0.015 (0) |

| T12 | 1 (3) | 0.06 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T43 | 16 (7) | 0.5 (4) | 0.25 (4) | |

| T44j | 0.25 (1) | <0.03 (0) | <0.015 (0) | |

| T60 | 0.5 (2) | 0.06 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T74 | 0.25 (1) | <0.03 (0) | <0.015 (0) | |

| T93 | 1 (3) | 0.125 (2) | 0.03 (1) | |

| T127 | 0.25 (1) | 0.03 (0) | <0.015 (0) |

Isolate designations beginning with P were from patients at HSC. Isolate designations beginning with T were from patients at the Toronto Hospital. Isolate designations ending with the same lowercase letter are from the same patient.

Character refers to the MIC coded from 0 to 9 on an exponential scale.

In addition to strains in our sample, two C. albicans reference strains, CAI4 and W0-1, were provided by P. T. Magee, University of Minnesota, and one, CA, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 90028). Strains were grown at 35°C on yeast-peptone-glucose (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% d-glucose, plus 1.5% agar for solid medium) and were stored in 1 ml of glycerol citrate (3% trisodium salt, 40% glycerol) at −70°C.

Species identification of the Candida isolates was by standard methods at HSC and the Toronto Public Health Laboratory (TPHL). Oral swabs were streaked on inhibitory mold agar (17) with 5 μg of ciprofloxacin per ml. Isolates that grew at 35°C within 7 days were subcultured to Sabouraud’s peptone-glucose agar at HSC. Isolates were tested for germ tube formation (13) in rabbit serum held at 35°C for 3 h; isolates positive for germ tubes were identified as C. albicans. The remaining isolates were grown on corn meal-Tween 80 agar (13) for morphological examination and were tested with commercial assimilation kits (API 20C; bioMérieux, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) for evaluation of physiological characters. Cultures not identified to a high confidence level with these techniques were referred to TPHL. At TPHL, isolates were grown on 2% oxgall medium (4); isolates that formed characteristic chlamydospores at 28°C after 48 h were identified as C. albicans sensu lato (inclusive of Candida stellatoidea and Candida dubliniensis). The remaining isolates were identified by reference techniques, including Wickerham broth fermentation and auxanographic assimilation of carbon and nitrogen substrates, the Christensen urease test, and a test for growth at 37°C (3, 7, 8, 13). These reference techniques facilitate identification of atypical isolates of C. albicans sensu lato that fail to produce germ tubes and/or chlamydospores. Subsequently, C. dubliniensis isolates were distinguished from C. albicans sensu stricto by poor or no growth at 42°C and no growth at 45°C within 72 h on Sabouraud’s peptone-glucose agar (6).

PCR amplification.

PCR mixtures (20 μl) contained 0.5 μM each primer, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1× PCR buffer II with 2 mM MgCl2 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.), 0.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), and 10 μl of a 100-fold dilution of genomic DNA prepared by the method of Scherer and Stevens (21). Amplifications were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp System 9600 thermocycler programmed for an initial denaturation at 95°C for 8 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C, primer annealing at 50 to 58°C (Table 2), and extension at 72°C for 20, 30, and 60 s, respectively, with a 5-min extension at 72°C on the final cycle.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes

| Locus (accession no.) | Oligonucleotide sequencec | Chromosome (SfiI fragment) | Temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C15F2a (Y07668) | 1. TAGTTAGTTTGCCTTGTTCC (amp) | 2 | 50 |

| 2. GAGAGCTACGTGAGCTCGTG (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. GCCCGCTGGTCATTGT (hyb) | 54 | ||

| 4. GCCCGCTGATCATTGT (hyb) | 51 | ||

| C12F10a,b (Y07664) | 1. ACGTAATAAGGGTATTGTTG (amp) | 1 | 50 |

| 2. GCAATTTGTCACTCATCCAG (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. ACCCCAACAATTGGT (hyb) | 43 | ||

| 4. ACCCCAAAAATTGGT (hyb) | 43 | ||

| 5. ACCACAGCAATTGGT (C. dubliniensis, hyb) | 41 | ||

| C2F7a,b (Y07669) | 1. GTTTGATCTGGAACGATCTC (amp) | 6 | 50 |

| 2. AGAAACCAACCAGCGTCTTC (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. GAATCTTGGGTCGAG (hyb) | 40 | ||

| 4. GAATCTTAGGTCGAG (hyb) | 33 | ||

| C2F10a (Y07666) | 1. TTGCTACTACAAATAGTCG (amp) | 1 | 50 |

| 2. GCTTAACATTTACCTGCTTC (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. ATTGCTCCGAACCCTTG (hyb) | 52 | ||

| 4. ATTGCTCCAAACCCTTG (hyb) | 49 | ||

| CHS2b (M82937) | 1. ACTACAGAAAAAGTTGTCCCCGTACA (amp) | R (B) | 50 |

| 2. TCTCCACTACTGTGTAAAAACTCCCCT (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. CAATGGCTTGGAAAC (hyb) | 42 | ||

| 4. CAATAGCTTGGAAAC (hyb) | 37 | ||

| 5. CAATTGCTTGGAAAC (C. dubliniensis, hyb) | 39 | ||

| C2F17a (Y07665) | 1. ACTAATCTATCGAGAGAACG (amp) | 3 | 50 |

| 2. GTCAGATGGTACGGACAAG (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. ACTTGGCCGACGAAG (hyb) | 48 | ||

| 4. ACTTGGTCGACGAAG (hyb) | 44 | ||

| ARG4 (L25051) | 1. TCACGGCAATTCTTGAACGAG (amp) | 7 (G) | 50 |

| 2. GCTAAAGCACCAGATCCTAATGGAG (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. GATGGGCTCATTGGT (hyb) | 44 | ||

| 4. GATGGGCACATTGGT (hyb) | 45 | ||

| 5. GATGGGCCCATTGGT (hyb) | 50 | ||

| CPH1b (U15152) | 1. AGCATTATCATTCCATTACGACGAGT (amp) | 1 | 50 |

| 2. TTTATATAGGTTGGGGTGGCGAC (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. TCTTCTGTGTTTCCATG (hyb) | 44 | ||

| 4. TCTTCTGAGTTTCCATG (hyb) | 45 | ||

| FAS2 (L29063) | 1. CTTACTTGCAAGAAGAAGCCGAGTT (amp) | 3 (P) | 55 |

| 2. TTCTGTTACCTGGAACAAGACCAGAC (amp) | 55 | ||

| 3. GCTCCATTGAGAGGA (hyb) | 43 | ||

| 4. GCTCCATTAAGAGGA (hyb) | 39 | ||

| GCN1 (S14D5)d | 1. CGCTTGTGGAAGTACTTGGG (amp) | 2 (A) | 55 |

| 2. GCTTGTCGTCAGACTCTTGTAAGG (amp) | 55 | ||

| 3. GTTGGTTGCCAATACC (hyb) | 46 | ||

| 4. GTTGGTTGCAAATACC (hyb) | 43 | ||

| PDE1b (L12045) | 1. TAATATGCTAGGTGGGGGTTCCTT (amp) | 5 (M) | 58 |

| 2. GCCCAATATGCCTAGTTTCAAAATC (amp) | 58 | ||

| 3. CTTTATAATCAAACCAC (hyb) | 36 | ||

| 4. CTTTATAATTAAACCAC (hyb) | 33 | ||

| LEU2 (AF000121) | 1. GGTGGTGGTCAAGAAAGAGG (amp) | 7 (C) | 58 |

| 2. CCAAGGCATCATCAGCTCC (amp) | 58 | ||

| 3. ACCCAATTCAACGGT (hyb) | 46 | ||

| 4. ACCCAATTTAACGGT (hyb) | 43 | ||

| CZF1 (M76586) | 1. CAATCTGTAGGTTACCTAGCGG (amp) | 4 (H) | 55 |

| 2. CCAGCAGCAGAATACAAAGG (amp) | 55 | ||

| 3. TACCCCAATGCACAG (hyb) | 46 | ||

| 4. TACCCCAGTGCACAG (hyb) | 46 | ||

| HEX1 (L26488) | 1. GTGAAGCTGCTTTATGGTCGGA (amp) | 5 (I) | 58 |

| 2. AGTATCATCGAGACTCGCGTGACT (amp) | 58 | ||

| 3. GATTTGTATAAAAATCC (hyb) | 36 | ||

| 4. GATTTGTACAAAAATCC (hyb) | 39 | ||

| 5. GATTTGTATAAAACACC (C. dubliniensis, hyb) | 36 | ||

| MNS1 (265162G08.y1.seq)d | 1. TTGGCCAATGCATTACACG (amp) | 1 | 53 |

| 2. CCGATTCACGATACATATCCC (amp) | 53 | ||

| 3. GGAGATTCTTATTACG (hyb) | 36 | ||

| 4. GGAGATTCCTATTACG (hyb) | 36 | ||

| ERG7b (L04305) | 1. TTGGCTGTTCTACGCGATCG (amp) | 2 (U) | 50 |

| 2. GCTGCCTCGCCTGAAGTATG (amp) | 50 | ||

| 3. GTTCACTTTCACATTCAGA (hyb) | 53 | ||

| 4. GTGGTTCACTTTCACTTTCACA (hyb) | 60 |

Sequences from Gräser et al. (5).

Oligonucleotides hybridize to the reverse complement of the accessioned sequence. Other oligonucleotides hybridize to the accessioned sequence.

amp, primer for amplification with corresponding annealing temperature; hyb, oligonucleotide probe with corresponding hybridization or wash temperature. Underlining indicates the polymorphic site.

Accession number for the Stanford Candida albicans Sequencing Project (http://alces.med.umn.edu/candida/geneinfo.html). Other accession for GenBank.

SSCP analysis.

Strains were screened for sequence-level polymorphisms by using single-strand conformation polymorphisms (SSCPs). Each primer (0.5 μM) was end-labeled with [γ-33P]ATP (60 fmol, 3,000 Ci/mmol; DuPont-NEN, Markham, Ontario, Canada) and polynucleotide kinase (0.1 U; Gibco BRL, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) at 37°C for 30 min. PCR analyses were performed as described above except that each end-labeled primer was added to all other reaction components to a final concentration of 0.5 μM in a volume of 12 μl. After cycling was complete, 4 μl of stop solution (95% formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.1% bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol) was added to the reaction mixtures. Reaction mixtures were heat denatured and applied to 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels with low cross-linking (2% bisacrylamide) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, with and without 7% glycerol. Electrophoresis was carried out at 150 V for 19 h for standard gels and 30 h for gels containing glycerol. Gels were transferred to filter paper, dried for 2 h at 80°C, and exposed to X-ray film (BIOMAX MR Kodak film) for 16 h at room temperature.

DNA sequencing.

DNAs of up to three representatives of each putative allelic class identified by SSCPs were sequenced. PCR products were purified by using the Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and then eluted in 10 μl of sterile distilled water. One microliter of a purified PCR product was sequenced directly by using the chain-terminating, dideoxynucleotide double-stranded DNA cycle sequencing system (Gibco BRL) and [γ-33P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; DuPont-NEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing reactions were subjected to electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions (SequaGel XR; National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Ga.).

Oligonucleotide hybridization.

Southern blots of PCR-amplified regions were prepared by standard procedures (18). Allele-specific oligonucleotides were end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; DuPont-NEN) and hybridized for 2 h to the Southern blots within 5°C of the midpoint temperature of the probe (Table 2) according to the protocol of Saville et al. (19). Three washes of 20 s each were done at the same temperature as the hybridization. The blots were then exposed to X-ray film at room temperature for 1 h.

Fingerprinting.

A 10-μl sample of DNA was digested with 10 U of EcoRI for 4 h at 37°C, and digestion was stopped by heating to 65°C for 10 min. Electrophoresis was carried out at 45 V for 22 h in 1% agarose gels in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. Southern blotting in 10× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) was by standard methods (18). Each blot was hybridized with the species-specific probe 27A in pBR322 labeled by nick translation with the Nick Translation System (Gibco BRL) and [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; DuPont-NEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each DNA fingerprint, each of 42 distinct DNA fragment size classes was scored as present or absent; genotypes were not inferred. Additional DNA fragments that hybridized weakly to probe 27A were not scored.

Susceptibility testing.

The susceptibilities of each strain to fluconazole were determined by the broth microdilution method using the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (M27-A) protocol (11). Fluconazole, supplied as a powder (Pfizer Inc., New York, N.Y.), was reconstituted in sterile distilled water to a concentration of 5,120 μg/ml and stored in aliquots at −70°C. Susceptibilities of each strain to fluconazole, ketoconazole, and itraconazole were also determined at HSC by use of the same procedure.

Distance analysis.

For all statistical analyses, distances were defined as the minimum number of steps required for the transition between two genotypes, where each step represented a genetic change, either (i) the mutation of one allele to another or (ii) the loss of an allele in a heterozygote as the result of mitotic crossing over or gene conversion. For example, the distance between genotype CC and CT at a given site was recorded as one step, and the distance between CC and TT was recorded as two steps. The total distance between two multilocus genotypes was the sum of the distances for all 16 sites, with a maximum possible of 32 steps. For the DNA fingerprints, the distance between the presence and the absence of a given band was recorded as one step for a possible maximum of 42 steps. The MIC data were coded with a character from 0 to 9 on an exponential scale. For example, the distance between MICs of 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml was two steps, and the distance between MICs of 0.125 and 64 μg/ml was nine steps. PAUP version 4.0b2 for Macintosh (D. L. Swofford, Smithsonian Institution) was used to calculate matrices of distances. Correspondence analysis was done as described by Legendre and Legendre (9).

RESULTS

Genotyping method.

Each of the 16 regions was amplified (Table 2) and examined for SSCPs under two different conditions. Putative alleles were identified on the basis of electrophoretic mobility. These alleles occurred in both homozygotes and heterozygotes. Up to three representatives of each putative allele were sequenced, and polymorphic nucleotide sites were identified (Table 3). For 16 sites that were polymorphic in the majority of isolates, allele-specific, oligonucleotide hybridization probes were designed (Table 2). In most cases, these probes contained a site of potential mismatch flanked by 7 to 8 bases. Each hybridization clearly indicated the presence or absence of an allele in an amplicon. Also, the intensity of the hybridization signal indicated whether an allele was present in (i) all of the molecules of an amplicon, as in a homozygote, or (ii) half of the molecules of an amplicon, as in a heterozygote. No anomalies were encountered in the 84 isolates of C. albicans, and the genotypic data for these isolates were complete.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide polymorphisms and genotype counts

| Locus | Polymorphic nucleotide position(s)a | Genotype (no. of strains)b |

|---|---|---|

| C15F2 | 174 | AA (21), AG (44), GG (19) |

| 207 (A, G)c | ||

| C12F10 | 218 | GG (68), GT (15), TT (1) |

| C2F7 | 50 (G, T) | |

| 68 (A, G) | ||

| 95 | CC (16), CT (2), TT (66)*** | |

| 119 (A, G) | ||

| 245 (C, T) | ||

| 260 (A, G) | ||

| C2F10 | 151 | AA (25), AG (14), GG (45)*** |

| CHS2 | 2028 (C, T) | |

| 2055 | CC (81), CT (0), TT (3)*** | |

| 2153 (A, G) | ||

| C2F17 | 206 | CC (46), CT (25), TT (13)** |

| 214 (A, G) | ||

| 257 (A, G) | ||

| ARG4 | 1789 | AA (20), CC (1), TT (18), |

| AC (38), AT (6), CT (1)*** | ||

| 1864 (C, T) | ||

| CPH1 | 1204 | AA (6), AT (61), TT (17)*** |

| 1213 (A, G) | ||

| 1258 (C, T) | ||

| 1261 (A, G) | ||

| 1616 (C, G) | ||

| 1687 (A, C) | ||

| 1771 (A, G) | ||

| FAS2 | 4671 (A, G) | |

| 4773 | AA (8), AG (35), GG (41) | |

| 4869 (A, T) | ||

| 4884 (C, T) | ||

| 4917 (C, T) | ||

| 4953 (C, T) | ||

| GCN1 | 145 | AA (3), AC (15), CC (66) |

| 235 (A, G) | ||

| PDE1 | 986 (A, G) | |

| 991 (A, G) | ||

| 1046 | AA (16), AG (51), GG (17) | |

| 1088 (A, G) | ||

| LEU2 | 96 (C, T) | |

| 190 | CC (31), CT (33), TT (20) | |

| CZF1 | 728 | AA (76), AG (7), GG (1) |

| HEX1 | 906 (A, G, T) | |

| 1915 (A, G) | ||

| 2063 (C, T) | ||

| 2070 (C, T) | ||

| 2080 (C, T) | ||

| 2089 | CC (54), CT (6), TT (24)*** | |

| 2109 (A, G) | ||

| 2135 (A, G) | ||

| 2179 (A, C) | ||

| MNS1 | 362 | CC (9), CT (12), TT (63)*** |

| ERG7 | 294 (indel) (AAAGTG)d | ++ (11), +− (46), −− (27) |

Polymorphic positions are relative to the accessioned sequences.

Diploid genotypes are followed by number of strains in parentheses. In all cases, the total number of C. albicans strains assayed was 84. **, counts significantly different from Hardy-Weinberg expectation at P < 0.05; ***, counts significantly different from Hardy-Weinberg expectation at P < 0.001.

Polymorphic positions whose alternative nucleotides are given in parentheses were found in the initial sequencing of representatives of each allelic class identified by SSCPs; these positions were not assayed in the complete set of 84 strains of C. albicans.

This polymorphism is for presence, indicated as a plus in the genotypes, or, for absence, indicated as a minus in the genotypes of the 6-nucleotide sequence shown in parentheses.

Atypical strains.

In the entire sample of 92 isolates (89 clinical isolates plus 3 reference isolates), 8 isolates were highly atypical (Table 4) relative to the remaining 84 isolates identified as C. albicans. Seven of these atypical isolates were later identified at TPHL as C. dubliniensis (T10, T12, T43, T44, T60, T74, and T127), and one was identified as C. tropicalis (T93). In these atypical isolates, some DNA regions amplified and hybridized to the allele-specific probes designed for the 84 isolates of C. albicans, while other regions either contained large numbers of sites with fixed differences relative to the C. albicans sequences or failed to amplify.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of atypical isolates of Candida

| Locus | Isolatea | Amplification | Hybridizing probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| C15F2 | T93a | + | 3/4 |

| T43 | + | − | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | − | ||

| C12F10 (AF149701)b | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 5 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | 5 | |

| C2F7 | T93 | + | 4 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | − | ||

| C2F10 | T93 | + | 3/4 |

| T43 | + | − | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | − | ||

| CHS2 (AF149703)c | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 5 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | 5 | |

| C2F17 | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | − | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60g, T74, T127 | + | − | |

| ARG4 (AF149702)d | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | 3 | |

| CPH1 | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | − | |

| FAS2 | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 4 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | 4 | |

| GCN1 | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | − | |

| PDE1 | T93 | + | 4 |

| T43 | + | − | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | − | |

| LEU2 | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | − | |

| CZF1 | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | − | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | − | ||

| HEX1 (AF149704)e | T93 | + | 3 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | 5 | |

| MNS1 (AF149705)f | T93 | + | 4 |

| T43 | + | 3 | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | 3 | |

| ERG7 | T93 | − | |

| T43 | + | − | |

| T10, T12, T44, T60, T74, T127 | + | − |

T93 was identified at TPHL as C. tropicalis, and the seven remaining atypical isolates were identified as C. dubliniensis.

GenBank accession no. for T10 sequence.

GenBank accession no. for T44 sequence.

GenBank accession no. for T10 sequence.

GenBank accession no. for T10 sequence.

GenBank accession no. for T10 sequence.

Did not amplify.

Multilocus genotypes of C. albicans.

Among the 84 isolates of C. albicans (81 isolates from patients plus 3 reference isolates), there were 64 multilocus diploid genotypes. Genotype counts at eight of the loci were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg expectation, while counts at eight loci deviated significantly from Hardy-Weinberg expectation (Table 3).

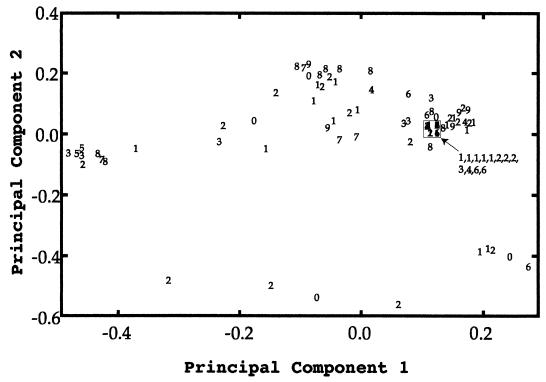

Variation among multilocus genotypes is represented by the ordination plot (9) in Fig. 1, in which the x-axis explains 26.7% of the variation and the y-axis explains 23.7% of the variation. The spatial positions of isolates in this plot are based on distances among their genotypes. In general, the closer two isolates are on the plot, the greater proportion of alleles they share. The spatial positions imply genotypic similarity but not relatedness (i.e., patterns of descent). This plot shows that isolates with very similar genotypes had a wide range of fluconazole MICs and, conversely, that isolates with the same MICs had diverse genotypes.

FIG. 1.

Ordination plot depicting variation among multilocus genotypes. The x-axis explains 26.7% of the variation, and the y-axis explains 23.7% of the variation. The numerical symbol plotted for each isolate is the MIC of fluconazole, coded with a character from 0 to 9 on an exponential scale. The proximity of isolates in this plot represents similarity among genotypes but does not imply relatedness (i.e., patterns of descent).

DNA fingerprints of C. albicans.

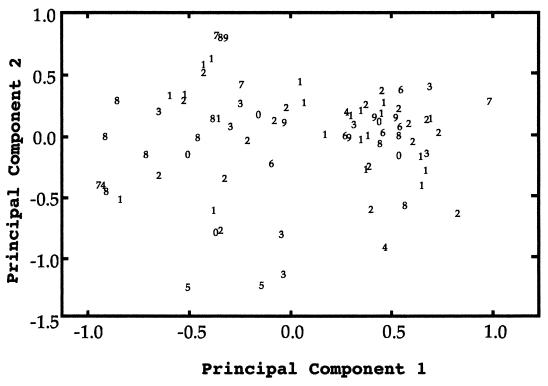

To test the discriminatory power of the genotyping system, DNA fingerprints were obtained by using the repetitive probe 27A. The DNA fingerprints distinguished 77 phenotypes among the 84 isolates of C. albicans. Variation among the fingerprints is represented by the ordination plot in Fig. 2 in which the x-axis explains 12.4% of the variation and the y-axis explains 9.5% of the variation. As in Fig. 1, the plot in Fig. 2 is based on distances among DNA fingerprints. In general, the closer two isolates are on the plot, the greater proportion of DNA fragments they share. This plot shows that there was a wide range of fluconazole MICs for isolates with very similar DNA fingerprints and, conversely, that the MICs were the same for isolates with diverse DNA fingerprints.

FIG. 2.

Ordination plot representing variation among DNA fingerprints. The x-axis explains 12.4% of the variation, and the y-axis explains 9.5% of the variation. The numerical symbol plotted for each isolate is the MIC of fluconazole, coded with a character from 0 to 9 on an exponential scale. The proximity of isolates in this plot represents similarity among the hybridizing fragments of DNA fingerprints but does not imply relatedness (i.e., patterns of descent).

Comparison of multilocus genotyping and DNA fingerprinting.

The discriminatory powers of this multilocus genotyping system and DNA fingerprinting with probe 27A were compared. Two groups of isolates having identical multilocus genotypes also had identical DNA fingerprints (T50 and T56; T63, T65, and T68); each of these groups of isolates was recovered from a single patient (Table 1). In other cases, isolates with identical multilocus genotypes were found to have nonidentical DNA fingerprints and, conversely, isolates with identical fingerprints had nonidentical multilocus genotypes. The combination of multilocus genotypes and DNA fingerprints distinguished 81 unique types among the total of 84 strains.

The multilocus genotype and DNA fingerprint data were compared in an additional two ways. First, in order to test for general linkage disequilibrium in this sample of C. albicans, distances based on multilocus genotypes were compared with distances based on DNA fingerprints. In 3,486 pairwise comparisons of strains, the correlation was both positive and highly significant (r = 0.465, P < 0.001).

Resistance to azole drugs.

The MICs of fluconazole ranged from 0.125 to 64 μg/ml, those of ketoconazole ranged from 0.03 to 16 μg/ml, and those of itraconazole ranged from 0.015 to 8 μg/ml for the isolates of C. albicans (Table 1). The correlation of resistance to fluconazole with resistance to ketoconazole and to itraconazole was highly significant (r = 0.692, P < 0.001, and r = 0.593, P < 0.001, respectively). Differences in fluconazole resistance were then compared with distances based on (i) multilocus genotypes and (ii) DNA fingerprints in the 3,486 pairwise comparisons among 84 strains of C. albicans. The mean pairwise distance based on (i) genotypes and (ii) fingerprints was compared to a distribution of mean distances expected under the null hypothesis of no relationship between MIC level and distance based on genotypes or fingerprints. For each MIC class, 10,000 samples of the same number of distances were randomly drawn, with replacement, from the set of all 3,486 pairwise distances for the 84 isolates of C. albicans (Table 5). In most cases, the observed mean distance was not significantly different from the null expectation; the observed mean distance fell well within the range of mean distances in the random samples. The only exceptions were groups MIC1 and MIC6, in which the observed mean distances were significantly less than random expectation.

TABLE 5.

P values for 10,000 randomizations

| Group | No. of cases | P value for genotype | P value for fingerprint |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC0 | 10 | 0.8564 | 0.249 |

| MIC1 | 231 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 |

| MIC2 | 153 | 0.9262 | 0.9495 |

| MIC3 | 21 | 0.7027 | 0.9866 |

| MIC4 | 3 | 0.1918 | 0.3879 |

| MIC5 | 1 | NTa | NT |

| MIC6 | 15 | 0.0021 | 0.0000 |

| MIC7 | 10 | 0.9661 | 0.6803 |

| MIC8 | 45 | 0.7833 | 0.8127 |

| MIC9 | 10 | 0.3782 | 0.2524 |

NT, not tested.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to determine if multilocus genotypes and DNA fingerprints predict variation in azole resistance in a sample of C. albicans isolates from HIV-infected patients as would be expected if variation in azole resistance was due to heritable differences among strains. Using a new genotyping system, we detected correlation between multilocus genotypes and 27A DNA fingerprints but did not detect correlation either between multilocus genotypes and azole resistance or between DNA fingerprints and azole resistance. Additionally, our genotyping method detected atypical isolates in the sample and has potential for identifying other Candida species.

The genotyping system developed here is based on polymorphisms in nucleotide sequences. The oligonucleotide hybridization assays are accurate, and the results are easily interpreted. Although all oligonucleotide hybridizations were done manually in this study, the same assays could readily be adapted for microchip technology (27) and automation. This would substantially increase throughput without loss of accuracy.

Clonal diversity in this sample was high, with 81 distinct types identified among 84 strains of C. albicans with the combination of multilocus genotypes and DNA fingerprints. This contrasts with other fungi also well known for clonal propagation (1, 2) in which certain genotypes were repeatedly recovered at much higher frequencies than any of the genotypes of C. albicans in this study. To test the resolving power of the new multilocus genotyping method, we compared its ability to distinguish clones of C. albicans with a reliable and widely used DNA fingerprinting method. Neither the multilocus genotyping nor DNA fingerprinting alone achieved “saturation” by identifying all of the 81 types identified by the combination of these two methods. Although fewer multilocus genotypes (64 genotypes) were identified in the sample of 84 strains of C. albicans than DNA fingerprint types (77 types), the number of loci assayed in the genotyping system could be increased without practical limit, resulting in enhanced discriminatory power.

In addition to distinguishing clones of this fungus, the multilocus genotyping system offers the possibility of phylogenetic analysis because both of the alleles present at each locus in this diploid genome are identified. Analysis of multilocus genotypes will be particularly useful in samples of highly related strains, such as in patients from which the fungus is sampled over time and in experimental populations in which, for example, loss of heterozygosity can be monitored over time. Assuming that C. albicans is predominantly clonal, it should also be possible to reconstruct a phylogeny of genotypes in larger samples of less-related strains such as the one sampled here. Reconstruction of the phylogeny of the 84 strains of C. albicans, however, was problematic for two reasons. First, the data set is large, including 84 strains (i.e., “taxa” in phylogenetic analyses), and it was not possible to find the shortest tree or trees from the set of all possible unrooted trees, regardless of the tree-building method. Second, there was a high level of homoplasy for individual characters in the neighbor-joining trees, which were slightly more parsimonious than the corresponding UPGMA trees. This homoplasy is not surprising; for example, a widespread ancestral genotype may lose heterozygosity in multiple, independent events of gene conversion or mitotic crossing over (20). Alternatively, genetic exchange and recombination can contribute to the homoplasy observed in trees that assume clonal evolution (25), although this interpretation may be less consistent with indications of linkage disequilibrium in this sample.

Because of the difficulty in representing relationships among the 84 genotypes of C. albicans as trees, we used instead an ordination plot to portray variation in multilocus genotypes (Fig. 1) and DNA fingerprints (Fig. 2); the advantage of this graphical method is that it does not force a bifurcating mode of evolution on the 84 isolates. In a comparison of multilocus genotypes and DNA fingerprints, the correlation of distances was positive and significant. This correlation is yet another indication of linkage disequilibrium in C. albicans and provides the framework for predicting other phenotypic traits from genotypic data based on neutral markers.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether fluconazole resistance in a sample of isolates from a group of HIV-infected patients could be predicted by multilocus genotype. With linkage disequilibrium, multilocus genotypes would be expected to be correlated with levels of drug resistance, but only if the drug resistance phenotype is stable relative to the genetic markers. Existing variation in azole resistance among strains could be due either to (i) differences among strains in their history of exposure to the selective pressure imposed by the presence of the drug, (ii) differences in the inherent potential of strains to develop drug resistance, or (iii) both. The absence of any meaningful correlation between genotype and drug resistance implies that the wide variation in fluconazole resistance is not due to inherent differences in the ability to develop drug resistance. If this were the case, then a correlation between genotype and drug resistance would be expected, whether the history of exposure to the drug was uniform or not. Instead, fluconazole resistance was strikingly variable, even within the two putative clones. The significance of the correlation between DNA markers and azole resistance may well vary among samples. But to be sufficiently predictive to be useful, the correlation would have to be much larger than in the present sample.

The presence of atypical isolates in our sample was unanticipated but provided the opportunity to detect a multitude of nucleotide sequence differences in the 16 nuclear loci that distinguished isolates of C. albicans from those of other species (Table 4). Of the 89 isolates initially identified as C. albicans, seven were later re-identified by conventional means as C. dubliniensis and one was identified as C. tropicalis. One oligonucleotide probe for locus C12F10 and one for locus CHS2 could potentially serve as molecular probes for C. dubliniensis since they were species specific in this study. One oligonucleotide probe for locus HEX1 was specific for all the C. dubliniensis isolates with the exception of one, T43, which was divergent in numerous loci from both the remaining C. dubliniensis isolates and the C. albicans isolates.

Among the 84 isolates conclusively identified as C. albicans, the lack of correlation between DNA markers and azole resistance suggests that azole resistance is either gained or lost too frequently to be predicted by the more stable DNA markers. We are currently testing this hypothesis by examining the development of drug resistance and measuring its stability in replicated experimental populations founded from the same initial genotype and exposed to inhibitory drug concentrations over many generations. Another explanation for the apparent lability of fluconazole resistance is that a single strain repeatedly challenged with a drug may approach different adaptive peaks by mutation in different sets of the genes determining fluconazole resistance. These include the target gene (ERG11), which encodes lanosterol 14 α-demethylase, the several efflux pumps capable of transporting fluconazole out of the cell, including the superfamily of ATP binding cassette transporters and the major facilitator superfamily, and any number of other genes affecting the expression of any of the above. We are currently examining all of these possibilities in experimental populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from Pfizer Canada and Research Grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada to L.M.K. and J.B.A. L.E.C. was supported by a NSERC Postgraduate Scholarship. Fungal susceptibility testing at HSC was supported by a grant from the MRC PMAC program to S.W. and S.R.

We thank P. T. Magee for furnishing reference isolates and the fingerprint probe and P. Peresneto for help with statistical analyses. We thank D. L. Swofford for the beta test version 4.0b2 of PAUP. We also thank M. Witkowska at TPHL for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson J B, Kohn L M. Clonality in soilborne, plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1995;33:369–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.33.090195.002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J B, Kohn L M. Genotyping, gene genealogies, and genomics bring fungal population genetics above ground. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett J, Payne R, Yarrow D. Yeasts: characteristics and identification. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer J, Kane J. Production of chlamydospores by Candida albicans cultivated on dilute oxgall agar. Mycopatholog Mycol Appl. 1968;35:223–229. doi: 10.1007/BF02050734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gräser Y, Volovsek M, Arrington J, Schönian G, Presber W, Mitchell T G, Vilgalys R. Molecular markers reveal that population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans exhibits both clonality and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12473–12477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkpatrick W, Revankar S, McAtee R, Lopez-Ribot J, Fothergill A, McCarthy D, Sanche S, Cantu R, Rinaldi M, Patterson T. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in North America by primary CHROMagar Candida screening and susceptibility testing of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3007–3012. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3007-3012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreger-van Rij N. The yeasts, a taxonomic study. 3rd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtzman C, Fell J. The yeasts, a taxonomic study. 4th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legendre P, Legendre L. Numerical ecology, 2nd English ed. New York, N.Y: Elsevier; 1998. Correspondence analysis; pp. 451–476. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lott T J, Holloway B P, Logan D A, Fundyga R, Arnold J. Towards understanding the evolution of the human commensal yeast Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:1137–1143. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odds F C. Resistance of yeasts to azole-derivative antifungals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:463–471. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pincus D, Salkin I. Human infections caused by yeast-like fungi. In: Wentworth B, Bartlett M, Robinson B, Salkin I, editors. Diagnostic procedures for mycotic and parasitic infections. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1988. pp. 239–269. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pujol C, Joly S, Lockhart S R, Noel S, Tibayrenc M, Soll D R. Parity among the randomly amplified polymorphic DNA method, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and Southern blot hybridization with the moderately repetitive DNA probe Ca3 for fingerprinting Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2348–2358. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2348-2358.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pujol C, Reynes J, Renaud F, Raymond M, Tibayrenc M, Ayala F J, Janbon F, Mallie M, Bastide J M. The yeast Candida albicans has a clonal mode of reproduction in a population of infected human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9456–9459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Pfaller M A. Resistance of Candida species to fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salkin I. Media and stains for mycology. In: Wentworth B, Bartlett M, Robinson B, Salkin I, editors. Diagnostic procedures for mycotic and parasitic infections. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1988. pp. 379–411. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saville B J, Kohli Y, Anderson J B. mtDNA recombination in a natural population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1331–1335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scherer S, Magee P T. Genetics of Candida albicans. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:226–241. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.226-241.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scherer S, Stevens D A. Application of DNA typing methods to epidemiology and taxonomy of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:675–679. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.675-679.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherer S, Stevens D A. A Candida albicans dispersed, repeated gene family and its epidemiologic applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1452–1456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor M, Feyereisen R. Molecular biology and evolution of resistance to toxicants. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:719–734. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibayrenc M. Are Candida albicans natural populations subdivided? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:253–254. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vilgalys R, Gräser Y, Schönian G, Presber W. Response to Tibayrenc. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:254–257. [Google Scholar]

- 26.White T C, Marr K A, Bowden R A. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winzeler E A, Richards D R, Conway A R, Goldstein A L, Kalman S, McCullough M J, McCusker J H, Stevens D A, Wodicka L, Lockhart D J, Davis R W. Direct allelic variation scanning of the yeast genome. Science. 1998;281:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Mitchell T G, Vilgalys R. PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses reveal both extensive clonality and local genetic differences in Candida albicans. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:59–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, Vilgalys R, Mitchell T G. Lack of genetic differentiation between two geographically diverse samples of Candida albicans isolated from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1369–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1369-1373.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]