Abstract

Background and Aims:

Primary obesity surgery endoluminal (POSE) is a primary endoscopic bariatric therapy focusing on gastric remodeling. The original POSE procedure involves placement of full-thickness plications in the fundus. Here we aim to assess the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of a novel POSE procedure that involves plications of only the gastric body to reduce the width and length of the stomach.

Methods:

This was a pilot study of patients who underwent a distal POSE procedure with gastric body plications for the treatment of obesity. Outcomes included technical success rate, serious adverse event (SAE) rate and efficacy of this novel POSE procedure at inducing weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities.

Results:

Ten patients (6 female, age 52±20) underwent a distal POSE procedure. Baseline BMI was 38.1±6.2 kg/m2. The technical success rate was 100%. An average of 21±4 plications were placed per case (6±2 for distal belt, 10±3 for suspenders, 4±2 for proximal belt, and 3±1 for fillers). The gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) was pulled distally by 3.0±1.6 cm. The gastric body was shortened by 11.0±5.1 cm, representing a 59% reduction. The SAE rate was 0%. At 6 months, the patients experienced 15.0±7.1% total weight loss (TWL), respectively. All patients (100%) achieved at least 5% TWL, and 8 patients (80%) achieved at least 25% excess weight loss. Hypertension, diabetes, GERD, and obstructive sleep apnea improved after the procedure.

Conclusion:

This novel POSE procedure, focusing on gastric body plication and sparing the fundus, is technically feasible and appears to be safe and effective for the treatment of obesity.

BACKGROUND

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are an emerging class of minimally invasive treatment options for obesity and its related comorbidities. To date, there are 2 categories of EBMT devices that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) including (1) space occupying devices (intragastric balloons and transpyloric shuttle) and (2) aspiration therapy. Additionally, there are 2 devices that are cleared by the FDA for tissue approximation in the stomach, which have been applied for bariatric indications. These include (1) an endoscopic suturing system (Overstitch, Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tex, USA) and (2) an endoscopic plication system (Incisionless Operating Platform (IOP), USGI Medical, San Clemente, Calif, USA)1,2. Traditionally, endoscopic suturing has focused on tightening the gastric body in an attempt to delay gastric emptying, whereas endoscopic plication has focused on reducing the gastric fundus to affect gastric accommodation. Specific suturing and plication patterns have continued to evolve in an effort to optimize patient outcomes; however, there are limited data and no consensus regarding which patterns are most effective3.

Traditional endoscopic plication (primary obesity surgery endoluminal [POSE]) emphasizing reduction of the gastric fundus has yielded mixed results, with a recent randomized controlled trial (ESSENTIAL trial) demonstrating 4.95% TWL at 1 year in the POSE arm compared with 1.38% TWL in the sham arm4. In contrast, the most commonly performed suturing procedure, endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which focuses on the gastric body, has resulted in approximately 16.5% TWL across studies with less variability3,5–10. Two recent meta-analyses comparing POSE to ESG suggested that ESG may result in greater weight loss, although the majority of the POSE studies were of a more rigorous RCT study design, with ESG studies being open-label, limiting the strength of this comparison11,12. Given the overall efficacy and more consistent outcomes associated with ESG, we hypothesize that modifying the plication pattern to focus on the gastric body, similar to that of ESG, may result in greater weight loss with less variability.

We have previously described a case report suggesting the technical feasibility of this novel concept13. Specifically, this new POSE procedure involves placement of plications only within the gastric body using a “belt-and-suspenders” pattern (Figure 1). The goal of the belt plications is to reduce the width of the stomach, whereas the suspender plications serve to shorten the length of the stomach. Although this pattern appears technically feasible, the safety and early efficacy remain unknown.

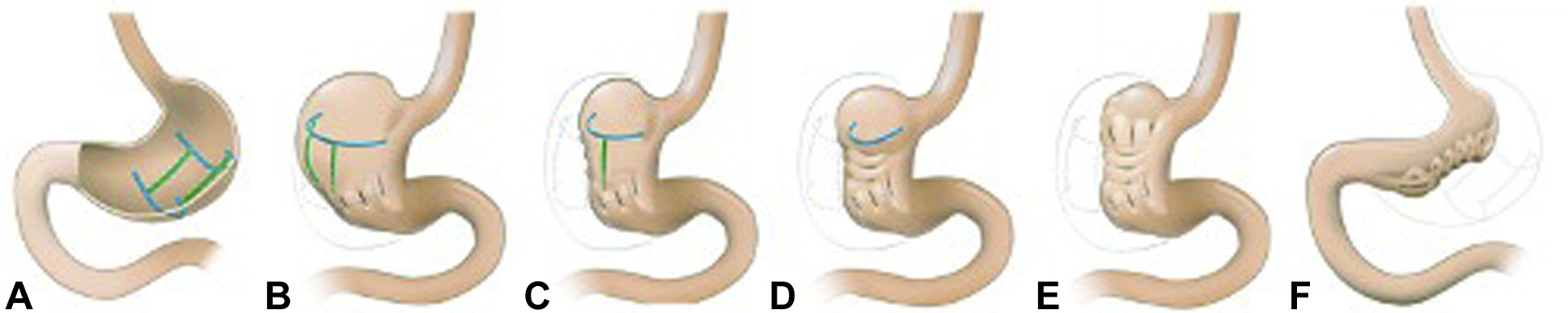

Figure 1.

Comparison of 2 primary obesity surgery endoluminal (POSE) procedures. A, The traditional POSE procedure involves placement of plications in the gastric fundus. B, The novel POSE procedure involves placement of plications in the gastric body. Figures were adapted with permission from Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:619-30 and Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. VideoGIE 2018;3:296–300.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a retrospective review of prospectively collected data of all consecutive patients who underwent a novel POSE procedure focusing on the gastric body for obesity. The study was conducted at a tertiary referral center with the bariatric center of excellence from December 2017 to July 2019. Patients with all classes of obesity with or without obesity-related comorbidities were included. Patients who underwent POSE using other plication patterns, such as those that involve fundic plications, were excluded. Patients who were eligible for bariatric surgery were referred for surgical consultation if one had not already been done. All available EBMTs were discussed with the patient. Final decision on which EBMT to pursue was made by the patient and family after consultation. Benefits and risks of the procedure were discussed with the patient before obtaining an informed consent. Patients underwent the procedure as per protocol. Demographics, obesity history and history of prior weight loss attempts were collected, as well as history of obesity-related comorbidities and medications. This study was approved by the Institution Review Board (IRB).

Description of the Novel POSE Technique

The distal POSE procedure was performed using the Incisionless Operating Platform (IOP) (USGI Medical, San Clemente, Calif, USA) (Figure 2). The platform consists of 4 components—(1) a 54F flexible transport with 4 working channels one of which is for passage of an ultraslim endoscope for visualization, (2) a g-Lix for tissue grasping, (3) a g-Prox for tissue approximation and for delivery of tissue anchors, which are preloaded in a catheter called (4) a g-Cath. The technique involved placement of plications solely in the gastric body using a “belt-and-suspenders” pattern. Specifically, the belt plications served to reduce the circumference and therefore the cross-sectional area of the stomach, whereas the suspender plications helped reduce the stomach length. First, the distal belt plications were placed in the distal body along the posterior surface extending to the anterior aspect of the greater curvature. Subsequently, 2 to 3 rows of suspender plications were formed in the mid gastric body along the anterior aspect of the greater curvature, posterior aspect of the greater curvature and/or posterior gastric body. Finally, the proximal belt plications were created in the proximal body. In some cases, “filler plications” were placed to fill in any gaps in the pattern (Figure 3, Video 1). On conclusion of the procedure, a diagnostic endoscopy was performed to evaluate the anatomy, assess for bleeding or mucosal injury, and measure gastric body length, defined as the difference between the location of the incisura (measured on the lesser curvature side) and the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ).

Figure 2.

The incisionless operating platform (IOP) (USGI Medical, San Clemente, Calif, USA).

Figure 3.

The novel POSE procedure using a “belt-and-suspenders” plication pattern. A, A “belt-and-suspenders” pattern with the blue lines representing belt plications and the green lines representing suspender plications. B, Distal belt plications. C, First row of suspender plications. D, Second row of suspender plications. E, Proximal belt plications. F, Final appearance with both the width and length of the stomach being reduced. Figures were adapted with permission from Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. VideoGIE 2018;3:296–300.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was technical success and procedural safety assessed using the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) adverse event lexicon14. Technical success was defined as placement of at least 2 plications in the correct orientation at each station (distal belt, first row of suspender, second row of suspender and proximal belt) and gastric body shortening of at least 2 cm. Additionally, the secondary outcome was amount of weight loss at 6 months reported using absolute weight loss (AWL) in kilograms (kg), percent total weight loss (%TWL) and percent excess weight loss (%EWL). Percent TWL was calculated using the formula: ([initial weight − follow-up weight] / initial weight) × 100. Percent EWL was calculated using the formula: (initial weight − follow up weight / excess body weight) × 100. The proportion of patients who achieved clinically significant weight loss, defined as TWL of at least 5%15–17 or EWL of at least 25%18, was also determined as well as changes in obesity-related comorbidities.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported using mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were reported using proportion (%). Pre- and post-weights and comorbidities were compared using a paired Student t-test or a Chi-squared test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Ten patients with obesity underwent the distal POSE procedure. Baseline characteristics and comorbidities are shown in Table 1. All patients (100%) had previously attempted lifestyle modification, with 4 patients (40%) having undergone commercial weight-loss programs. All patients (100%) reported weight regain after initial successful weight loss after lifestyle intervention. Three patients (30%) had tried weight loss medications including phentermine (1), liraglutide (1) and topiramate followed by liraglutide (1). Six patients (60%) were qualified for bariatric surgery but elected not to undergo surgery (5) or were deemed to be too high risk (1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and comorbidities before the distal POSE procedure.

| Characteristics | N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52 ± 20 |

| Sex (female, %) | 6 (60) |

| Preprocedural weight (kg) | 112.0 ± 26.7 |

| Preprocedural BMI (kg/m2) | 38.1 ± 6.2 |

| Obesity class (n, %) | |

| - Obesity class II | 3 (30) |

| Obesity-related comorbidities (n, %) | |

| - Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 3 (30) |

| - Hyperlipidemia | 2 (20) |

Technical success rate was 100%. All cases (100%) were performed under general anesthesia and with fellow participation. Average procedural time was estimated to be 101±24 minutes. Average number of plications was 21±4 per case. Breakdown of plication locations was as follows: distal belt: 6±2, first row of suspenders: 4±1, second row of suspenders: 3±2, third row of suspenders: 4±1, proximal belt: 4±2, and fillers: 3±1. The location of GEJ was at 41.0±2.4 cm and 44.0±3.1 cm from the incisors before and after the procedure, respectively. On average, the GEJ was pulled down distally by 3.0±1.6 cm after the procedure. The location of the incisura measured from the lesser curvature side was at 58.6±7.8 cm and 50.8±4.3 cm from the incisors before and after the procedure, respectively. On average, the gastric body length was reduced by 11.0±5.1 cm after the procedure, representing a 59% reduction (Figure 4). Average device cost per patient was approximately 6500 U.S. dollars. Six patients (60%) were discharged home on the day of the procedure as per our protocol. Four patients (40%) were admitted for nausea and emesis after the procedure with an average hospital length of stay of 2.5±1 days. All patients (100%) were given antibiotics for 3 days after the procedure, prescribed PPI and placed on liquid diet for 45 days. After 45 days, all patients (100%) were referred to registered dietitian for maintenance nutritional counseling, which included 1200 kcal solid diet daily. Additionally, all patients were counseled to participate in at least 150 minutes per week of physical activity, which must include resistance training.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic images of the novel POSE procedure. A, Stomach before the procedure. B, Distal belt plications. C, First row of suspender plications. D, Second row of suspender plications. E, Proximal belt plications. F, Final appearance with both the width and length of the stomach being reduced. Blue lines represent the reduction of the circumference of the stomach. Green lines represent the reduction of the length of the stomach.

There were no intraprocedural or postprocedural serious adverse events (0%). Three intraprocedural adverse events (30%) were reported, all of which were graded as mild. These were superficial esophageal mucosal abrasion requiring no intervention (3). Postprocedural adverse events were reported in 4 patients (40%) and were all graded as mild14. Specifically, all of these patients experienced nausea and emesis after the procedure, despite intraprocedural intravenous anti-emetics, requiring a hospital stay.

Average weight loss was 15.0±7.1 %TWL, which corresponded to 37.9±20.0% EWL at an average follow-up time of 6 (range 4–13) months. There was no loss to follow-up. All patients (100%) achieved at least 10% TWL and 8 patients (80%) achieved at least 25% EWL at 6 months. No adjunctive weight loss medications were prescribed after the procedure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes after the distal POSE procedure.

| Outcomes | |

|---|---|

| Technical success (n, %) | 10 (100%) |

| - Procedural time (minutes) | 101±24 |

| - Number of plications per case | 21±4 |

| - Esophageal lengthening (cm) | 3.0±1.6 |

| - Gastric body reduction (cm) | 11.0±5.1 |

| Serious adverse events (n, %) | 0 (0) |

| - Intraprocedural adverse events (n, %) | 3 (30) |

| - Postprocedural adverse events (n, %) | 4 (40) |

| Efficacy at 6 months | |

| - Total weight loss (%) | 15.0±7.1 |

| - Excess weight loss (%) | 37.9±20.0 |

| - Achieving ≥5% TWL (n, %) | 10 (100) |

| - Achieving ≥25% EWL (n, %) | 8 (80) |

Overall, obesity-related comorbidities improved after the procedure. Mean SBP decreased from 147±9 mm Hg to 120±9 mm Hg (p=0.01). Mean DBP decreased from 78±12 mm Hg to 71±8 mm Hg (p=0.45). Out of 5 patients with hypertension, 2 (40%) were able to discontinue antihypertensive medications and 3 (60%) were able to decrease their antihypertensive dosages after the procedure. Out of 3 patients with T2DM, 2 (67%) were able to decrease the insulin and oral hypoglycemic agent dosages. The other one was maintained on only metformin. Specifically, one patient decreased his insulin dose from 125 units of U-500 insulin daily to 25 units of NPH insulin daily. The other patient was able to discontinue dulaglutide. Average hemoglobin A1c decreased from 8.9±2.2% to 8.5±1.9% (while off medicines). All 3 patients (100%) with GERD experienced improvement in their acid reflux symptoms, with one being able to discontinue PPI (33%) and 2 (67%) being able to decrease the PPI dose. One out of 2 patients (50%) with hyperlipidemia was able to discontinue statin, and both patients (100%) with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) reported symptom improvement and ability to discontinue his continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

DISCUSSION

This series demonstrates that this novel gastric body plication procedure has a high rate of technical success as demonstrated by accuracy of plication placement and substantial shortening of the gastric body. Additionally, the procedure appears safe with no SAEs according to the ASGE lexicon. Early efficacy data are also encouraging.

Traditionally, POSE involves placement of full-thickness plications primarily in the fundus. The procedure was first performed by Horgan in 2008 in Argentina with several subsequent studies resulting in heterogenous outcomes19–21. Specifically, in 2017, a randomized controlled trial (MILEPOST trial) including 44 patients was conducted in 3 European centers (Austria, Spain, and the Netherlands). In this trial, the average numbers of plications in the fundus and distal gastric body were 8.8 and 4.2, respectively. At 12 months, patients in the POSE arm experienced 13.0% TWL, compared to 5.3% TWL in the control arm (p<0.01)22. Subsequently, a U.S. multicenter randomized sham-controlled trial (ESSENTIAL trial) including 332 patients was conducted. At 12 months, patients in the POSE arm experienced 4.95% TWL, compared to 1.38% in the sham arm (p<0.0001)4. Although it is unclear why the efficacy of traditional POSE remains heterogenous, it has been hypothesized that the study design of the ESSENTIAL trial, which included a double-blind control with an active sham may have reduced the overall weight loss.

In contrast to traditional POSE, this novel distal POSE procedure focuses on plication placement primarily in the gastric body. Although the fundus is spared from direct plication placement, the overall length of the stomach is reduced by approximately 11.0 cm, representing a 59% reduction. This is likely due to the suspender plications, which are oriented longitudinally along the length of the stomach. Additionally, with the belt plications, the width of the stomach is further reduced making the stomach a sleeve-like structure, although this is harder to quantify. This significant alteration in gastric anatomy may have a more profound impact on gastric emptying rate, whereas fundus plications are thought to primarily affect gastric accommodation. It is possible that altering the rate of gastric emptying has more effect on satiety and satiation than altering gastric accommodation. This hypothesis, however, will need to be proven in future prospective studies. Furthermore, a secondary effect of gastric shortening is elongation of the intra-abdominal esophagus, similar to what is seen in esophageal lengthening surgical procedures such as the Collis gastroplasty. This is believed to lengthen the high-pressure zone, which may result in improvement of GERD symptoms.23–26. This suggests that the anatomical effect of this procedure may offer a solution for patients with obesity and reflux who would otherwise not be good candidates for sleeve gastrectomy.

In our study, the overall weight loss is 14.3% TWL at 6 months. These results appear comparable with ESG (15.1% TWL at 6 months)5. Additionally, as this new technique similarly focuses on the gastric body, it may offer more consistent outcomes than the original POSE procedure. Although direct comparisons cannot be made between these techniques given the heterogeneity in several factors, such as study design, patient selection and operators, these results are promising. Future studies to evaluate longer term efficacy and physiologic effects of this new procedure are warranted.

This study has a few limitations. First, the number of patients is relatively small. However, this study is intended to serve as a proof-of-concept study to demonstrate technical success, safety and early efficacy of a new technique. Second, the analysis of changes in comorbidities appears to be underpowered. These findings should serve as a trend and may be used to assist with study design for a future, larger, prospective study that is powered to detect these changes in comorbidities and their relevant medication usages. Last, our group is part of a bariatric center of excellence and has performed approximately 2,000 suturing and plication cases with various devices over the past 15 years. This may impact the generalizability of these results. Nevertheless, in our experience, this device appears to be intuitive and user-friendly. Of note, although it may be more technically challenging to perform revisional procedures, these are typically less time consuming and of lower risk. As such, we believe it is better to start with revisional work before performing primary procedures.

In conclusion, this new POSE procedure, which involves the placement of plications solely in the gastric body, may represent a safe and effective primary endoscopic bariatric procedure. In our series, patients lost approximately 15% of their initial weight. These results are encouraging and suggest that POSE may provide a minimally invasive treatment option for many patients with obesity. Additionally, it appears to be effective at improving GERD symptoms, suggesting that this may provide an alternative for some patients interested in sleeve gastrectomy but with underlying GERD. There is also evidence for improvement of other comorbidities in addition to GERD, and further studies to clarify these findings, as well as to evaluate physiologic mechanisms and long-term efficacy, would be of interest.

Supplementary Material

Video 1. The novel POSE procedure using a “belt-and-suspenders” plication pattern.

Conflict of Interest:

P.J. has received research support from Apollo Endosurgery, Fractyl and GI Dynamics, and has served as a consultant to Endogastric Solutions and GI Dynamics. C.C.T. has served as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Apollo Endosurgery,, Fractyl, USGI Medical, Medtronic/Covidien, Olympus/Spiration and GI Dynamics, has served as an advisory boards member for USGI Medical and Fractyl, has received research grant and support from USGI Medical, Apollo Endosurgery, Olympus/Spiratio, Aspire Bariatrics and Spatz and GI Dynamics, has served as a general partners for Blueframe Healthcare, and holds stock and royalties for GI Windows.

Acronyms

- POSE

Primary Obesity Surgery Endoluminal

- SAE

serious adverse event

- TWL

total weight loss

- EBMTs

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IOP

Incisionless Operating Platform

- ESG

endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- GEJ

gastroesophageal junction

- ASGE

American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- AWL

absolute weight loss

- kg

kilograms

- %TWL

percent total weight loss

- S.D.

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethical Statement:

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Human Research Committee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sullivan S, Edmundowicz SA, Thompson CC. Endoscopic Bariatric and Metabolic Therapies: New and Emerging Technologies. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Endoscopic Bariatric and Metabolic Therapies: Surgical Analogues and Mechanisms of Action. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:619–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Moura DTH, de Moura EGH, Thompson CC. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty: From whence we came and where we are going. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019;11:322–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan S, Swain JM, Woodman G, Antonetti M, De La Cruz-Muñoz N, Jonnalagadda SS, et al. Randomized sham-controlled trial evaluating efficacy and safety of endoscopic gastric plication for primary obesity: The ESSENTIAL trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedjoudje A, Dayyeh BA, Cheskin U, Adam A, Neto MG, Badurdeen D, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. Aug 20; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, Galvao Neto MP, Sahdala NP, Shaikh SN, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc 2018;32:2159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharaiha RZ, Kedia P, Kumta N, DeFilippis EM, Gaidhane M, Shukla A, et al. Initial experience with endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty: technical success and reproducibility in the bariatric population. Endoscopy 2015;47:164–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Nava G, Sharaiha RZ, Vargas EJ, Bazerbachi F, Manoel GN, Bautista-Castaño I, et al. Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty for Obesity: a Multicenter Study of 248 Patients with 24 Months Follow-Up. Obes Surg. 2017. Apr 27; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrichello S, Hourneaux de Moura DT, Hourneaux de Moura EG, Jirapinyo P, Hoff AC, Fittipaldi-Fernandez RJ, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in the management of overweight and obesity: an international multicenterstudy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019. Jun 19; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alqahtani A, Al-Darwish A, Mahmoud AE, Alqahtani YA, Elahmedi M. Short-term outcomes of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in 1000 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:1132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan Z, Khan MA, Hajifathalian K, Shah S, Abdul M, Saumoy M, et al. Efficacy of Endoscopic Interventions for the Management of Obesity: a Meta-analysis to Compare Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty, AspireAssist, and Primary Obesity Surgery Endolumenal. Obes Surg 2019;29:2287–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gys B, Plaeke P, Lamme B, Lafullarde T, Komen N, Beunis A, et al. Endoscopic Gastric Plication for Morbid Obesity: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Published Data over Time. Obes Surg 2019;29:3021–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Gastric plications for weight loss: distal primary obesity surgery endoluminal through a belt-and-suspenders approach. VideoGIE 2018;3:296–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, Luecking C, Kirbach K, Kelly SC, et al. Effects of Moderate and Subsequent Progressive Weight Loss on Metabolic Function and Adipose Tissue Biology in Humans with Obesity. Cell Metab 2016;23:591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swift DL, Johannsen NM, Lavie CJ, Earnest CP, Blair SN, Church TS. Effects of clinically significant weight loss with exercise training on insulin resistance and cardiometabolic adaptations. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:812–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sei Sports Exerc 2009;41:459–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force and ASGE Technology Committee, Abu Dayyeh BK, Kumar N, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda S, Larsen M, et al. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:425–438.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinós JC, Turró R, Mata A, Cruz M, da Costa M, Villa V, et al. Early experience with the Incisionless Operating Platform™ (IOP) for the treatment of obesity : the Primary Obesity Surgery Endolumenal (POSE) procedure. Obes Surg 2013;23:1375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Espinós JC, Turró R, Moragas G, Bronstone A, Buchwald JN, Mearin F, et al. Gastrointestinal Physiological Changes and Their Relationship to Weight Loss Following the POSE Procedure. Obes Surg 2016;26:1081–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-Nava G, Bautista-Castaño I, Jimenez A, de Grado T, Fernandez-Corbelle JP. The Primary Obesity Surgery Endolumenal (POSE) procedure: one-year patient weight loss and safety outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015;11:861–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller K, Turró R, Greve JW, Bakker CM, Buchwald JN, Espinós JC. MILEPOST Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial: 12-Month Weight Loss and Satiety Outcomes After pose SM vs Medical Therapy. Obes Surg 2017;27:310–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu R, Addo A, Broda A, Sanford Z, Weltz A, Zahiri HR, et al. Update on the Durability and Performance of Collis Gastroplasty For Chronic GERD and Hiatal Hernia Repair At 4-Year Post-Intervention. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019. Nov 25; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritter MP, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Gadenstätter M, Oberg S, Fein M, et al. Treatment of advanced gastroesophageal reflux disease with Collis gastroplasty and Belsey partial fundoplication. Arch Surg 1998;133:523–8; discussion 528–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvath KD, Swanstrom LL, Jobe BA. The short esophagus: pathophysiology, incidence, presentation, and treatment in the era of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Ann Surg 2000;232:630–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L-Q, Ferraro P, Martin J, Duranceau AC. Antireflux surgery for Barrett’s esophagus: comparative results of the Nissen and Collis-Nissen operations. Dis Esophagus 2005;18:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1. The novel POSE procedure using a “belt-and-suspenders” plication pattern.