Abstract

Genes encoding SHV-1 and SHV-2 were sequenced by different methods. Nucleotide sequencing of the coding strand by standard dideoxy-chain termination methods resulted in errors in the interpretation of the nucleotide sequence and the derived amino acid sequence in two main regions which corresponded to nucleotide and amino acid changes that had been reported previously. The automated thermal cycling method was clearly superior and consistently resulted in the correct sequences for these genes.

SHV β-lactamases confer resistance to a broad spectrum of β-lactam antibiotics and are of great therapeutic concern for infections caused by many species of the family Enterobacteriaceae. SHV-1, the original member of the SHV β-lactamase family, is present in most strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae and may be either chromosomally or plasmid mediated. A plasmid-mediated SHV-1 is also commonly found in Escherichia coli and is seen in other genera as well. The first extended-spectrum β-lactamase to be described was an SHV-type enzyme that differed from the SHV-1 amino acid sequence by a single residue and was subsequently designated SHV-2 (10). Since that time, at least 12 SHV-type derivatives have been described. The various derivatives of SHV-type β-lactamases differ from SHV-1 by amino acid substitutions at only a few amino acid residues (Table 1). From the beginning of the study of the SHV-type enzymes, there has been confusion about the amino acid sequence of some of the SHV derivatives. There have been a number of sequences reported that have amino acid deletions or additions in portions of the SHV protein that are usually conserved (11, 17, 18). In addition, the amino acid sequence derived from the nucleotide sequence published by Mercier et al. for SHV-1 differs from those that were obtained by direct amino acid sequencing of the protein (4).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of SHV derivatives

| SHV variant | pI of β-lactamase | Amino acid no.a

|

Source or reference | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 35 | 43 | 54 | 130 | 140 | 141 | 179 | 192 | 193 | 193x | 205 | 238 | 240 | |||

| SHV-1 | 7.6 | NDb | Leu | Arg | Gly | Ser | Thr | Ala | Asp | Lys | Leu | — | Arg | Gly | Glu | 4 |

| Ile | Asn | Val | Gly | 11 | ||||||||||||

| Ile | Leu | Arg | Gly | Ser | Ala | Thr | Asp | Lys | Leu | — | Arg | Gly | Glu | This study | ||

| SHV-2 | 7.6 | ND | Thr | Ala | — | Serc | 5 | |||||||||

| — | Ser | 8, 9, 15, this study | ||||||||||||||

| SHV-2a | 7.6 | Gln | — | Ser | 16 | |||||||||||

| SHV-3 | 7.0 | — | Leu | Ser | 12 | |||||||||||

| SHV-4 | 7.8 | ND | — | Leu | Ser | Lys | 14 | |||||||||

| SHV-5 | 8.2 | — | Ser | Lys | 6 | |||||||||||

| SHV-6 | 7.6 | Ala | — | 3 | ||||||||||||

| SHV-7 | 7.6 | Phe | Ser | — | Ser | Lys | 7 | |||||||||

| SHV-8 | 7.6 | Asn | — | 19 | ||||||||||||

| SHV-9 (SHV-5a) | 8.2 | — | Arg | Asn | Val | Gly | Ser | Lys | 18 | |||||||

| SHV-10 | 8.2 | — | Gly | Arg | Asn | Val | Gly | Ser | Lys | 18 | ||||||

| SHV-11 | 7.6 | Gln | — | 13 | ||||||||||||

| SHV-12 | 8.2 | Gln | — | Ser | Lys | 13 | ||||||||||

| OHIO-1 | 7.0 | Phe | Ser | Phe | Phe | Ala | — | 21 | ||||||||

| LEN-1 | 7.0 | Val | Gln | — | Gln | 2 | ||||||||||

Amino acid sequence numbers according to Ambler et al. (1). Boxed area represent sequence variations addressed in this study. —, no amino acid reported at this position. For more information regarding the amino acid sequences of SHV-type β-lactamases, see reference 10a.

ND, not done. The amino acid sequence obtained by protein sequencing, and therefore it does not contain the amino acids in the signal sequence. All others are putative amino acid sequences obtained from nucleotide sequencing.

Amino acids in boldface represent substitutions from SHV-1 (4) resulting in new SHV-type enzymes.

During a previous sequencing project involving an SHV-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase, it was noted that when nucleotide sequencing was performed by traditional dideoxy-chain termination methods, the sequencing gels contained a large number of areas of compressions that were difficult to read (7). It was observed that some of these compressions occurred in the exact locations where the amino acid additions or deletions had been reported previously by other investigators. It was theorized that the confusion among various blaSHV sequences occurred because of the difficulty in interpretation of the DNA sequence. Therefore, a study was done to attempt to resolve the differences seen with the various reported sequences of SHV derivatives and to evaluate the sequencing methodologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strain used for the sequencing of SHV-1 by traditional dideoxy-chain termination methods was E. coli DH5α(pCLL3411) (7). The strains used for automated thermal cycle sequencing were PCR clones generated from E. coli HB101(pMON 38) expressing SHV-1 (11) and JC2926(pBP60-1) expressing SHV-2 (10) (kindly provided by George A. Jacoby.)

Nucleic acid techniques.

To generate the clones used in the thermal cycling experiments, the SHV genes were first amplified by PCR by standard methods (20). The primers used were as follows: forward, 5′GTATTGAATTCATGCGTTATATTCGCCTGTGTA3′; and reverse, 5′CAGAATTCGGCTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCGAT3′. The primers were designed to flank the start and stop codons of the blaSHV-1 gene to amplify the entire coding region. The resulting PCR products were cloned into pCR 2.1-TOPO by using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Clones from three independent PCRs were generated and sequenced.

DNA sequencing was performed on double-stranded plasmid DNA by several methods. Both strands of the entire SHV-1 gene on pCLL3411 were sequenced by traditional sequencing methods with a nested set of primers identical to and complementary to the blaSHV-1 coding sequence. These were selected so that they did not anneal to regions of the gene corresponding to base pair changes associated with previously determined extended-spectrum SHV gene DNA sequences. The oligonucleotide primers used in traditional sequencing reactions were as follows: SHV-F1, 5′CGGCCCTCACTCAAGGATG3′ SHV-F2, 5′GGGTGGATGCCGGTGACG3′ SHV-F3, 5′CCGCTGGGAAACGGAACTG3′ SHV-F4, 5′GGGATTGTCGCCCTGCTTGG3′ SHV-R1, 5′GCGGCTGCGGGCTGGCGTG3′ SHV-R2, 5′CCTGCGGGGCCGCCGACGG3′ SHV-R3, 5′CCACTGCAGCAGCTGCCG3′ SHV-R4, 5′GCACGGAGCGGATCAACGG3′ SHV-R5, 5′CGCCCGGCACGCTGCGAGG3′

Traditional dideoxy-chain termination sequencing was performed with a Sequenase kit (United States Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) with 35S-dATP label (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (23). The Sequenase kit was used with three different nucleotide triphosphate mixtures containing dGTP, dITP, or 7-deaza-dGTP. Thermal cycle sequencing reactions of PCR-cloned blaSHV-1 and blaSHV-2 genes were performed according to the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, FS (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (22). The cycle sequencing reaction was performed with GeneAmp PCR system 9600 (ABI-PE), also according to the protocol. Spin columns were employed to remove unincorporated dye-labeled nucleotides after cycle sequencing. Automated DNA sequencing-grade 4.75% polyacrylamide gels were run for DNA sequencing samples by using ABI 373 DNA sequencers.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data for blaSHV-1 and blaSHV-2 determined in this study are listed in GenBank under accession no. AF148850 and AF148851, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

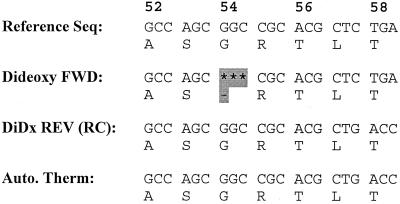

The nucleotide sequence obtained by traditional dideoxy-chain termination with blaSHV-1 resulted in numerous compressions on the sequencing film. Interestingly, two of these areas of compression were found in regions of the blaSHV-1 gene sequence that corresponded to amino acid substitutions noted in previously published reports (11, 17, 18). As shown in Fig. 1 and 2, the nucleotides comprising the codon for amino acid 54 appeared to be absent when a sequencing film was examined visually. This apparent deletion of glycine 54 was reported in several SHV-type sequences (17, 18). However, these nucleotides were present when the sequence was determined for the noncoding strand or when the sequence was generated by the automated thermal cycling method.

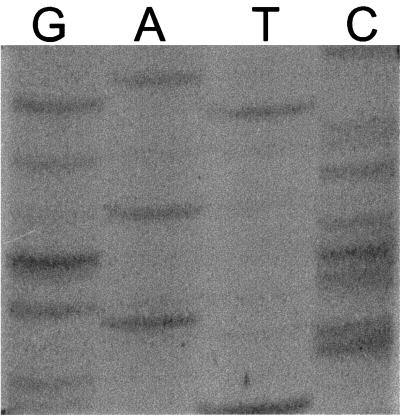

FIG. 1.

Sequencing gel of nucleotides 142 through 160 for blaSHV-1. The autoradiograph shows the compressions that occur in this region following sequencing reactions performed by the dideoxy-chain termination method. The photograph was taken with a Kodak DC120 digital camera and converted to an electronic file by using PhotoEnhancer (Pictureworks).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of sequences of nucleotides 142 through 160 of blaSHV-1. Numbers above the nucleotide sequence indicate the amino acid according to the designation of Ambler et al. (1). Reference Seq is the only published nucleotide sequence for SHV-1 (11). Dideoxy FWD was obtained by dideoxy-nucleotide chain termination sequencing with a forward primer. DiDx REV (RC) is the reverse complement of sequence obtained by standard dideoxy-chain termination sequencing of the noncoding strand with a reverse primer. Auto. Therm was obtained by thermal cycling sequencing reactions followed by running the reactions in an automated sequencing unit. The area of compression that caused a discrepancy is shaded. This compression was such that the three nucleotides corresponding to the glycine were not observed.

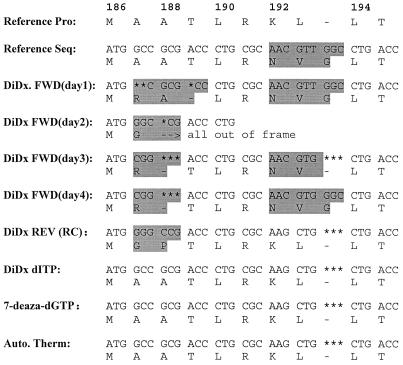

For some of the areas, the observed compressions gave different results on individual testing days (Fig. 3). For example, nucleotides encoding amino acids 187 to 189 were quite different, depending on the day of the test. These differences could be due to variations in individual sequencing reactions or the resolving capabilities of individual gels. Furthermore, this area of discrepancy was not resolved by sequencing the noncoding strand. However, the correct sequence was obtained by substitution of dITP or 7-deaza-dGTP for dGTP in the sequencing reaction by the dideoxy-chain termination method. The correct sequence was also obtained by automated thermal cycling.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of sequences of nucleotides 544 through 573 of blaSHV-1. Numbers above the nucleotide sequence indicate the amino acid according to the designation of Ambler et al. (1). Reference Pro was obtained by sequencing the SHV-1 protein (4). Reference Seq is the only published nucleotide sequence for blaSHV-1 (11). The DiDx. FWD (days 1 to 4) sequences were obtained by standard (dGTP mix) dideoxy-chain termination sequencing with a forward primer on 4 separate days. DiDx REV (RC) is the reverse complement of sequence obtained by standard dideoxy-chain termination sequencing of the noncoding strand with a reverse primer. DiDx dITP was obtained by substituting dITP for dGTP in the sequencing reaction mixture. 7-deaza dGTP was obtained by substituting 7-deaza-dGTP for dGTP in the sequencing reaction mixture. Auto. Therm was obtained by thermal cycling sequencing reactions followed by running the reactions in an automated sequencing unit. The area of compression which caused a discrepancy is shaded.

Amino acid substitutions of Lys192Asn and Leu193Val have been described by several investigators (11, 17, 18). In addition, these investigators reported the addition of a glycine residue between amino acids 193 and 194. As shown in Fig. 3, every time that sequencing was performed by dideoxy-chain termination on the coding strand of DNA, the resultant amino acid sequence was this exact combination of derived amino acids (Lys192Asn, Leu193Val, and the addition of glycine between residues 193 and 194). However, if nucleotide sequencing was performed with the noncoding strand, by substituting dITP or 7-deaza-dGTP for GTP, or by automated sequencing methods, the derived amino acid sequence was identical to that obtained by protein sequencing of SHV-1 (4). The latter sequence appears to be completely conserved for this region of the protein among all of the other reported sequences for SHV derivatives (Table 1).

This study indicates that errors in sequences for SHV-type derivatives can easily arise due to a common difficulty in reading films generated by the dideoxy-chain termination method. These errors have been shown to result in the deletion of an amino acid residue at position 54, the addition of a residue between amino acids 193 and 194, and substitutions at positions 192 and 193. Many of these compressions were particularly insidious, because to the eye they did not appear to be the usual G-C-type compressions, in that it was not inherently obvious that a compression had occurred. Only after sequencing the noncoding strand or by using an alternative deoxynucleotide triphosphate for dGTP in the sequencing reactions did the discrepancy come to light. It must be noted, however, that the sequencing of the noncoding strand and the use of the alternative deoxynucleotide triphosphates dITP and 7-deaza-dGTP introduced compressions and tended to introduce ambiguity at other locations (data not shown). Therefore, it is essential that one or more of the methods used to resolve the sequence for the dideoxy-chain termination method be used in conjunction with the original forward sequencing method.

In this study, the automated thermal cycling method consistently produced results that were in line with the consensus for blaSHV gene sequences. The blaSHV genes are more G-C rich (G+C content = 61%) than other class A β-lactamases (G+C content = 49, 41, and 50% for blaTEM-1, blaPSE-1, and blaOXA-1, respectively). The large amount of guanine and cytosine residues found in blaSHV-1 accounts for the increased number of compressions that were observed in traditional sequencing methods. The automated system uses a thermal cycling reaction that melts the DNA molecule during the sequencing reaction, thereby reducing the number and/or the severity of compressions that occur with more standard sequencing methods. This problem would not be unique to the T7 DNA polymerase found in the Sequenase kit, but would be common to all polymerases that work at low temperatures.

The results of this study show that the sequencing of genes encoding SHV-type β-lactamases is not as straightforward as the sequencing of other β-lactamase genes. It has been demonstrated that sequencing errors may be reported if only the forward sequencing reaction of manual methods is performed. Therefore, at the very least, it is essential to sequence both strands of the blaSHV gene, although not all of the discrepancies were resolved by sequencing the noncoding strand.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Eric Beer for excellent technical assistance with the automated sequencing, Tim Murphy for help with photography, and Steven J. Projan for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P, Coulson A F W, Frére J-M, Ghuysen J-M, Joris B, Forsman M, Levesque R C, Tiraby G, Waley S G. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1991;276:269–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Kido N, Fujii Y, Komatsu T, Kato N. Close evolutionary relationship between the chromosomally encoded β-lactamase gene of Klebsiella pneumoniae and the TEM β-lactamase gene mediated by R plasmids. FEBS Lett. 1986;207:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arlet G, Rouveau M, Philippon A. Substitution of alanine for aspartate at position 179 in the SHV-6 extended-spectrum β-lactamase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barthélémy M, Peduzzi J, Labia R. Complete amino acid sequence of p453-plasmid-mediated PIT-2 β-lactamase (SHV-1) Biochem J. 1988;251:73–79. doi: 10.1042/bj2510073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthélémy M, Péduzzi J, Yaghlane H B, Labia R. Single amino acid substitution between SHV-1 β-lactamase and cefotaxime-hydrolyzing SHV-2 enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billot-Klein D, Gutmann L, Collatz E. Nucleotide sequence of the SHV-5 β-lactamase gene of a Klebsiella pneumoniae plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2439–2441. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.12.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford P A, Urban C, Jaiswal A, Mariano N, Rasmussen B A, Projan S J, Rahal J J, Bush K. SHV-7, a novel cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, identified in Escherichia coli isolates from hospitalized nursing home patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:899–905. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garbarg-Chenon A, Godard V, Labia R, Nicolas J-C. Nucleotide sequence of SHV-2 β-lactamase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1444–1446. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.7.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huletsky A, Couture F, Levesque R C. Nucleotide sequence and phylogeny of SHV-2 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1725–1732. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Jacoby, G., and K. Bush. 1999. Amino acid sequences for TEM, SHV and OXA extended-spectrum and inhibitor resistant β-lactamases. [Online.] http://www.lahey.org/studies/webt.htm SHV. [1 November 1999, last date accessed.]

- 10.Kliebe C, Nies B A, Meyer J F, Tolxdorff-Neutzling R M, Wiedemann B. Evolution of plasmid-coded resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:302–307. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercier J, Levesque R C. Cloning of SHV-2, OHIO-1, and OXA-6 β-lactamases and cloning and sequencing of SHV-1 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1577–1583. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.8.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolas M-H, Jarlier V, Honore N, Philippon A, Cole S T. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding SHV-3 β-lactamase responsible for transferable cefotaxime resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:2096–2100. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.12.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nüesch-Inderbinen M T, Kayser F H, Hächler H. Survey and molecular genetics of SHV-β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae in Switzerland: two novel enzymes, SHV-11 and SHV-12. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:943–949. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Péduzzi J, Barthélémy M, Tiwari K, Mattioni D, Labia R. Structural features related to hydrolytic activity against ceftazidime of plasmid-mediated SHV-type CAZ-5 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:2160–2163. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.12.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podbielski A, Melzer B. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the SHV-2 β-lactamase (blaSHV-2) of Klebsiella ozaenae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4916. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Podbielski A, Schönling J, Melzer B, Warnatz K, Leusch H-G. Molecular characterization of a new plasmid-encoded SHV-type β-lactamase (SHV-2 variant) conferring high-level cefotaxime resistance upon Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:569–578. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-3-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prinarakis E E, Miriagou V, Tzelepi E, Gazouli M, Tzouvelekis L S. Emergence of an inhibitor-resistant β-lactamase (SHV-10) derived from an SHV-5 variant. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:838–840. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prinarakis E E, Tzelepi E, Gazouli M, Mentis A F, Tzouvelekis L S. Characterization of a novel SHV β-lactamase variant that resembles the SHV-5 enzyme. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;139:229–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasheed J K, Jay C, Metchock B, Berkowitz F, Weigel L, Crellin J, Steward C, Hill B, Medeiros A A, Tenover F C. Evolution of extended-spectrum β-lactam resistance (SHV-8) in a strain of Escherichia coli during multiple episodes of bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:647–653. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shlaes D M, Currie-McCumber C, Hull A, Behlau I, Kron M. OHIO-1 β-lactamase is part of the SHV-1 family. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1570–1576. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.8.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spurgeon S L, Chen S, Koepf S. Improvements in dye primer and dye terminator sequencing with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, FS. Microb Comp Genomics. 1996;1:254–255. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabor S, Richardson C C. DNA sequence analysis with a modified bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4767–4771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]