Abstract

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in sub-Saharan Africa have high HIV incidence. Despite scale-up of programmatic delivery and demand creation activities in this population, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake is low. To explore community perceptions around AGYW PrEP use, we conducted four focus group discussions (FGDs) between October and December 2018 with 26 Community Advisory Board (CAB) members in Kenya. Conventional content analysis and thematic network analysis were used to identify themes relating to community perceptions of PrEP use among AGYW. CAB members noted community perception of PrEP use as unacceptable for AGYW because of the potential to increase “promiscuous” behavior, STIs, and pregnancy. AGYW may face stigma if PrEP is mistaken for HIV treatment, and may fear HIV testing or accessing PrEP because of a lack of youth-friendly services. PrEP can be integrated into maternal and child health and family planning clinics, which are routinely accessed by AGYW and lack the stigma associated with HIV clinics. PrEP scale-up among AGYW will require continued community sensitization to address concerns, reduce stigma, and clarify misperceptions.

Keywords: Adolescents, female, community health, HIV prevention, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), qualitative

In East and Southern Africa, adolescent girls and young women (AGYW), ages 15–24 years, experience high HIV incidence, accounting for 26% of new HIV infections while making up only 10% of the regional population (UNAIDS, 2017a). In 2016, it was estimated that more than 10,000 new HIV infections occurred among adolescent girls ages 15–19 years in Kenya, more than double the number of infections in males of the same age (UNAIDS, 2017b). That same year, the Kenya Ministry of Health (MOH) released guidelines on the provision of oral, daily tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention to individuals with high HIV acquisition risk, including AGYW as a target population (Ministry of Health - Kenya, 2016).

Ongoing programmatic rollout of PrEP in Kenya involves multiple delivery points, including HIV treatment clinics (known as Comprehensive Care Clinics [CCCs] in Kenya), maternal and child health (MCH) and family planning (FP) clinics, and community safe spaces (Pintye et al., 2018). PrEP uptake among AGYW in recent implementation projects in Kenya ranges from 5.4% to 19% (Kinuthia et al., 2018; Mugwanya et al., 2018; Oluoch et al., 2019). Additionally, less than 40% of AGYW who initiate PrEP continue use after 1 month (Mugwanya et al., 2019). Barriers to effective PrEP use for AGYW operate both in clinical settings and outside of the clinic, in community, family, and dyadic relationships. As PrEP access expands in high-burden settings where AGYW are a target group, it is important to understand the multi-level factors influencing PrEP use in this priority population. Prior studies have identified stigma, service delivery issues, and misinformation as influential barriers in various populations and settings (Kambutse et al., 2018; Mack et al., 2014; Mack et al., 2015; Mullens et al., 2018; Van Der Straten et al., 2014). Improved counseling, peer education, and community delivery points have been identified as potential facilitators to PrEP use (Mack et al., 2014; Mack et al., 2015). Despite recognition of community factors as important for programmatic success of PrEP, few data are available on community-level perceptions influencing PrEP use among AGYW.

Community stakeholders are often included in HIV research through the use of Community Advisory Boards (CABs; Community Partners, 2014). CABs advise research staff by identifying public safety and other community support systems, providing feedback on the effects of research on the community, proposing solutions to mitigate challenges, and offering suggestions for programmatic improvements. Representing diverse voices, CABs express community and stakeholder sentiments about research, as well as perspectives on knowledge and effectiveness of interventions in the communities they represent (Community Partners, 2014). Additionally, CABs can help garner support among the community and foster an environment of mutual trust and increased awareness (Community Partners, 2014).

In this study, we explored community perceptions around PrEP use among AGYW by conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) with CAB members from two large-scale PrEP implementation programs in Western Kenya with the overall goal of informing PrEP scale-up activities for AGYW in this setting.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We recently completed a large demonstration program, the PrEP Implementation for Young Women and Adolescents (PrIYA) Program, where PrEP services were integrated within routine MCH and FP clinics in Kisumu County, Kenya (Mugwanya et al., 2018; Mugwanya et al., 2019; Pintye et al., 2018). In the PrIYA Program, more than 20,000 women were screened from July 2017 to June 2018 and more than 3,900 initiated PrEP (PrIYA Final Report, 2019). We are also conducting the ongoing PrEP Implementation for Mothers in Antenatal Care (PrIMA) Study, a cluster-randomized trial to evaluate PrEP delivery approaches for more than 4,000 pregnant women within MCH clinics in Homa Bay and Siaya Counties, Kenya (Dettinger et al., 2019). Both PrIYA and PrIMA evaluate PrEP uptake among AGYW and include CABs to provide guidance in implementation.

We conducted four FGDs with CAB members between October and December 2018. FGDs took place in three counties and equally spanned the PrIYA and PrIMA projects – Siaya County (n = 1; PrIMA), Homa Bay County (n = 1; PrIMA), and Kisumu County (n = 2; PrIYA). To achieve maximum recruitment, FGDs were held immediately prior to or following CAB meetings. CAB members included representatives from the education sector, religious groups, youth groups, and women’s groups, as well as county government leaders, health care workers (HCWs), and health system administrators. To leverage existing relationships and trust, participants in each FGD were sampled from the same CAB. Study coordinators invited all 40 CAB members to participate. While sample size was limited by the number of CAB members available and interested in participating, continued engagement with community members by study staff during and after study completion validated that our sample was enough to reach thematic saturation.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by the Kenyatta National Hospital-University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee (ERC). All study participants provided written informed consent. Reimbursement for transportation costs (1,000 Kenyan Shillings – approximately 10 USD) was provided to each participant.

Data Collection

FGDs were conducted using a semi-structured discussion guide with open-ended questions to explore participant beliefs and experiences related to PrEP, including, (a) perceived knowledge and attitudes toward PrEP use among AGYW in the participants’ communities, (b) factors influencing availability and use of PrEP for AGYW, (c) suggestions for improving PrEP delivery to AGYW, and (d) whether they would recommend PrEP to a sister or close female friend. The FGD guide was piloted with PrIYA staff and revised to optimize language, phrasing, and ordering of questions.

Each FGD was facilitated by one of two trained Kenyan female social scientists who were not affiliated with PrIYA or PrIMA. A Kenyan note-taker affiliated with PrIYA was present during each FGD but did not facilitate or participate in the discussion. Prior to each FGD, participants completed short surveys to collect basic demographic information. FGDs were conducted primarily in English, but participants were encouraged to speak in their preferred language, either Kiswahili or Dholuo, as they felt comfortable and use local phrases as needed to explain concepts. FGDs were recorded using a digital audio recorder, transcribed verbatim by the interviewer, and Kiswahili or Dholuo phrases were translated to English for analysis. Following each FGD, interviewers summarized the discussion in a debrief report structured using the topics in the FGD guide. FGDs lasted between 67 and 86 minutes.

Data Analysis

The goal of analysis was to explore themes relating to community perceptions of PrEP use among AGYW. FGDs were analyzed using a combination of conventional content analysis and thematic networks analysis, developing codes inductively and identifying and arranging themes into networks (Attride-Stirling, 2001; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Debrief reports were used to develop a preliminary codebook, which was refined based on review of the full-length transcripts (Simoni et al, 2019). The codebook was generated using both inductive and deductive methods through an iterative process with study staff and social scientists. Deductive codes were identified from literature reviews and content included in the FGD guide. Inductive codes were developed directly from the data, using open coding. The codebook was structured into categories based on key discussion topics (e.g., PrEP knowledge, decision-making, and availability). All transcripts were imported into ATLAS.ti 8 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and coded using the final version of the codebook by two U.S.-based scientists with extensive experience conducting HIV research in Kenya. Coders independently reviewed and coded half of the transcripts, then swapped and reviewed each other’s application of the coding framework. Memos and codes were created and applied in parallel to ensure systematic application of codes and interpretation of concepts across all transcripts. Disagreements in code application were resolved through group discussion between the larger study team. The team synthesized coded data to understand themes underlying community perceptions of PrEP and perspectives on PrEP use, specifically among AGYW in Western Kenya.

Results

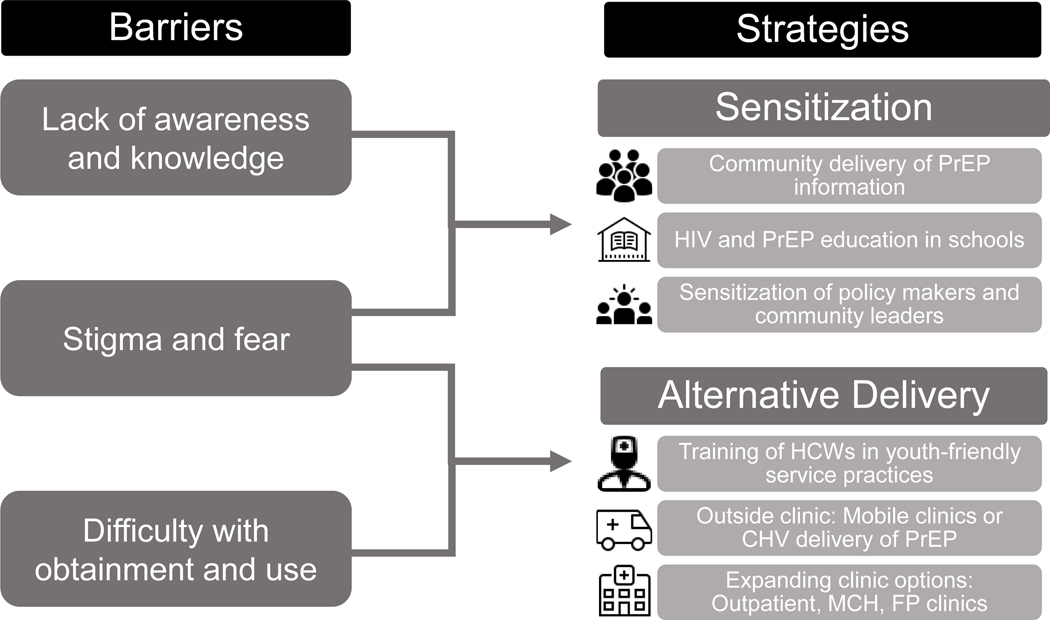

Twenty-six CAB members participated in four FGDs (Table 1). Each FGD included participants representing different stakeholder categories and included at least one health care worker, one youth representative, and one women’s group representative. Participants were a median of 37 years, primarily female (73%), with some university/college-level education (58%), and represented leadership from the government, health, education, and religious sectors, and youth and women’s groups in the community. Overall, CAB members were accepting of PrEP use among AGYW, but noted key barriers influencing low uptake and continuation among this population. Our analysis of the FGDs identified three major themes relating to PrEP use among AGYW: 1) AGYW lack awareness and knowledge about PrEP, and myths about PrEP are prevalent, 2) Stigma and fears associated with using PrEP, and 3) Barriers for obtaining and using PrEP among AGYW. To address these barriers to PrEP scale-up for AGYW in Kenya, CAB members recommended alternative delivery approaches, sensitization, sustainable support, and involving AGYW in policymaking (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of FGD Participants

| Characteristic | n (%) or Median (IQR) N = 26 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37 (28–46) |

| Female | 19 (73%) |

| Years of education completed | 15 (12–17) |

| Highest level of education started | |

| Primary | 1 (4%) |

| Secondary | 9 (35%) |

| Polytechnic | 1 (4%) |

| University/College | 15 (58%) |

| Role in CAB | |

| Health care worker | 9 (35%) |

| Youth representative | 6 (23%) |

| Women’s group representative | 5 (19%) |

| County government representative | 3 (12%) |

| Education sector representative | 2 (8%) |

| Religious group representative | 1 (4%) |

Note. FGD = Focus Group Discussion, CAB = Community Advisory Board.

Figure 1.

Barriers and Strategies to Increase Scale-Up of PrEP

Note. PrEP = Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus, HCW = Health Care Worker, CHV = Community Health Volunteer, MCH = Maternal and Child Health, FP = Family Planning.

AGYW Lack Awareness and Knowledge About PrEP, and Myths About PrEP are Prevalent

According to CAB members, lack of PrEP awareness and knowledge, misinformation, and low risk perception have led to poor uptake of PrEP, especially among AGYW in Western Kenya. CAB members described several inaccuracies about PrEP eligibility and duration of use commonly observed among AGYW. CAB members noted confusion among AGYW about how long PrEP should be used, with many believing that PrEP must be taken for life. Although not a commonly held view, multiple participants shared that they have heard some say that PrEP is a way of “ensuring everyone is on pills” or that the government encourages PrEP use because it does not want donated ARVs to “expire or go to waste,” CAB members also noted fears among AGYW that if they took PrEP and acquired HIV, currently available HIV treatments would be ineffective. This could potentially be a conflation of PrEP use during undiagnosed acute HIV infection, which can lead to drug resistance in certain cases.

Some people feel that when you are negative when you are taking it, in [the] future, in case you become positive…the ARVs may not be able to work; it may cause resistance. – Female Health Care Worker

Other myths identified by CAB members centered around the negative impact of PrEP on pregnancy, which especially impacts AGYW interested in having children. CAB members described fears around giving birth to a “deformed child” or PrEP leading to infertility.

I think there is also some myths associated with it which bring fear…that it can also interfere with [the] unborn child and even lead to giving birth to a deformed child or something also to do with long-term effect; it can also cause some diseases like cancer… – Male County Government Representative

In my area… some people are telling me that PrEP is the way of reducing them to bear children and others say that PrEP is not real to prevent the HIV; it is a way that comes… to reduce their years to be on this earth. – Religious Group Representative

Many participants voiced concerns that PrEP sensitization has not effectively reached the general community, especially the youth. CAB members described how alternative methods, such as condoms and voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), are more widely known and understood by the community due to more extensive health campaigns in the past. In addition, schools and religious groups are not supportive of PrEP use, and instead promote abstinence only.

When it comes to religion and education they don’t support the access of PrEP, so many times we have tried to access many school[s] just to teach about PrEP, but they give us certain topics [to avoid]... No talking about condoms, no talking about PrEP, no talking about PEP, all you do is talk about taking [ARVs]…that is it. – Female Youth Representative

Stigma and Fears Associated with Using PrEP

Although not unique to PrEP use among AGYW, participants in all four FGDs echoed the community’s confusion of PrEP as both a drug for HIV prevention and an antiretroviral drug (ARV) used for HIV treatment. CAB members described how PrEP looks the same as ARVs for HIV treatment in terms of size, color, and packaging. In some facilities, PrEP is also delivered through HIV care clinics (CCC), where people living with HIV receive treatment and pick up medications. CAB members noted fears from community members that if you are seen at the same clinic where people go for HIV treatment, you are assumed to be living with HIV.

Nobody wants to be associated with ARVs, so PrEP is [an] ARV and therefore [AGYW say] I should not be seen with a tin…carrying the drugs. – Female County Government Representative

Also negatively influencing PrEP uptake among AGYW is the community perception that PrEP promotes “immorality” and “promiscuity.” CAB members noted concerns about sexual activity among adolescents and discomfort with supporting something that might promote sexual activity in this population.

The perception of the community in general is that [PrEP] is a way of encouraging immorality among the youth because they go into the sexual scene and then they go and take [PrEP] to prevent HIV and AIDS, so it is a way of promoting [sexual activity] now. – Female Women’s Group Representative

Although almost all FGD participants said that they would recommend PrEP to others, one participant said that she would not consent to her unmarried daughter using PrEP, as “that is sexual sin.” Participants shared the community’s fear that PrEP use will lead to increased incidence of STIs and pregnancies among AGYW, as PrEP users will neglect to use condoms and other contraceptive methods, a behavior known as sexual risk compensation.

The few parents that I have come across are totally against it. They feel that their adolescents are being exposed… and they are being allowed to have unprotected sex as much as possible because now there is prevention of HIV and it is the HIV that they fear most and not even the pregnancies. – Female County Government Representative

Some FGD participants expressed that AGYW, especially unmarried women, are more likely to experience behavior-related stigma. Many are still living with their older relatives, who may disapprove of their PrEP use and make adherence challenging, or who may mistakenly think their AGYW is someone living with HIV. CAB members viewed stigma as less of an issue for women engaging in transactional sex and described how the protective benefits of PrEP gave women confidence when their clients refused condom use.

Some community sexual workers believe that it is the safest mode to use because the moment you start using it, you are safe, you are 100% safe, you are just sure that in the event that you get a client who doesn’t want to use a condom for you…you are safe. – Female Women’s Group Representative

When asked about fears regarding PrEP use, several participants listed side-effects they have heard community members share. Many of these side effects are perceived to be associated with ARVs for HIV treatment, including weight gain, dizziness, nausea, and rash. Participants discussed these side-effects as deterrents to PrEP use for general health reasons and for fear of being perceived to be HIV-positive.

What I have heard is some say that their skin will be rough and dry. Some also say that they get big and fat and pulpy. – Female Women’s Group Representative

Barriers for Obtaining and Using Prep Among AGYW

Several participants said that AGYW do not seek PrEP because they are afraid to know their HIV status and they do not like the requirement to re-test due to the emotional stress and logistical barriers HIV testing entails.

If you compare this age, you will find that at that age many people are afraid to know their HIV status as compared to the older pregnant women… [To use PrEP] it is a must you have to know your status. So if you compare, the younger age, they will be afraid to know their status so they won’t be for the PrEP. – Female Youth Representative

Additionally, facilities and HCWs providing PrEP are perceived as being over-worked and not youth-friendly. Even if an AGYW seeks out PrEP, she may not feel comfortable disclosing her risk behaviors if she feels judgment from the provider, which could also lead to poor adherence. Pregnant AGYW who may be coming to terms with their maternity status may feel even more reluctant to seek care and start to make decisions about their pregnancy, including initiating PrEP.

They come to the ANC (antenatal care/clinic) expectant, naïve, helpless… Opening up is a challenge and here the nurses have a queue to clear and… [AGYW] require ample time with adequate information to make a decision. – Female Health Care Worker

Participants disagreed about whether AGYW find PrEP preferable to condoms. Some participants said that condoms can be obtained more discreetly, while PrEP requires a health facility visit and screening. Others stated that AGYW prefer PrEP because it can be taken in secret, whereas condom use must be negotiated with one’s partner.

I know women will use PrEP more than men…because women are not really taking control in negotiation when it comes to sex; men normally make the decision on when and where to have sex, so with that one it becomes very difficult sometimes to negotiate about safe sex. So, they prefer when they have something which they can control. So, I know women will use it more. – Male County Government Representative

Prep Scale-Up Should Prioritize Alternative Delivery Approaches and Sensitization

CAB members identified several community and health care system-level strategies that could improve PrEP uptake among AGYW. PrEP scale-up should consider alternative delivery points, other than HIV treatment clinics, which are associated with HIV seropositivity and treatment. CAB members suggested expanded delivery points, including outpatient, MCH, and FP clinics. FP clinics provide an ideal delivery point for AGYW because these clinics could simultaneously provide access to PrEP and prevention education messaging around STIs and pregnancy.

CAB members noted that for any PrEP delivery system to be acceptable to AGYW, privacy and confidentiality must be prioritized. In addition, HCWs should be trained to offer youth-friendly services. An education sector representative suggested creating “youth-friendly points where AGYW can pick the drugs”. Outside the facility, CAB members noted that PrEP delivery through community health volunteers (CHVs) could improve access and adherence. Many CAB members felt that screening and initiation should continue to be done at a health facility, but that CHVs could take refills “to their door step,” removing the need for repeated facility visits. However, some suggested that PrEP should only be stored at the health facilities to avoid mishandling by those who are untrained. Mobile facilities were one delivery strategy that CAB members believed could help reduce stigma.

When we have mobile clinics, it will be like a normal thing. Stigma will be reduced and the people will be taking it as a normal thing and, therefore, it is not harmful to have PrEP drugs with you. You can walk in any time and out and pick your PrEP whenever you want as opposed to having it in a fixed place like in a hospital. – Female Health Care Worker

Participants made suggestions about possible sensitization strategies. CHVs, midwives, or peer educators could be trained to sensitize the community about PrEP. Several participants recommended that the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education work together to integrate health education and PrEP information into the school curriculum in secondary schools and in colleges. Youth could also be reached in youth forums, where they would be more comfortable sharing their views and asking questions. Importantly, participants acknowledged the need to first sensitize policy makers and community leaders.

Even the leaders themselves, we have not reached them with enough information…so as much as we are saying that we have not sensitized the adolescents, even the leaders themselves we have not done much to reach them with this information about PrEP and they still live with those myths and misconceptions. – Male County Government Representative

PrEP Scale-Up Requires Sustainable Support and Youth Involvement

All FGDs discussed PrEP availability, stating that PrEP is available in all government health facilities: “PrEP is available…everywhere…it’s like oxygen.” Participants perceived that the government and its non-governmental partners have provided PrEP to meet the current demand, but “if we increase demand, then there will be need to increase funding for it.” They expressed concern that further demand creation, including activities to increase awareness about PrEP, and rapid expansion in uptake might negatively influence availability. There is also concern about the sustainability of PrEP, given the current mechanisms supporting access.

PrEP has been spearheaded by most of the partners…but these projects are short lived… I think on the government side we have not really allocated finances to continue with these programs without the partners. So we are seeing a gap especially in terms of sustainability…So I know this discussion will also be used as resource [for] mobilization so that we can continue with the programs at the end of the programs, which the partners are running, and eventually, it can be taken over fully by the government. – Male County Government Representative

Effective and sustainable implementation will require the consultation of key opinion leaders. Notably, participants emphasized the importance of involving adolescents in policymaking.

I would tell them to involve the adolescents in making that policy; like when they are in that board meeting, the adolescents should be there because this is about them. It is not about you guys; you are making policies according to you and according to your own perception and the kind of funding that you are having, not caring about us like what we are going through…where we are. – Female Youth Representative

Discussion

This qualitative study was conducted among community stakeholders within three counties in Kenya where programmatic PrEP delivery for AGYW is ongoing. Our analysis revealed multiple factors perceived as barriers to PrEP use among AGYW: Myths and misconceptions about PrEP among AGYW are thought to persist within the community due to poor sensitization, limited delivery approaches that are currently only facility-based, and persistent disease- and behavior-related stigma. Our participants also identified potential solutions for addressing these challenges, including focusing community-level PrEP messaging to dispel misinformation, expanding PrEP access points for AGYW, and working directly with AGYW and community leaders to increase PrEP demand. To meet PrEP targets and prevent new HIV infections among AGYW most at-risk, it will be increasingly important for PrEP programs to consider community perspectives as PrEP scale-up continues.

Recent studies have explored topics related to the general use of PrEP in several sub-Saharan African countries, through qualitative interviews, focus groups, and consultations (Kambutse et al., 2018; Mack et al., 2014, Mack et al., 2015; Mullens et al., 2018; Van Der Straten et al., 2014; Wheelock et al., 2012). Consistent with our findings, community members in these studies identified misinformation and misconceptions as significant barriers to PrEP uptake (Kambutse et al., 2018; Mack et al., 2014, Mack et al., 2015; Mullens et al., 2018; Van Der Straten et al., 2014; Wheelock et al., 2012). Our data suggest that even in communities where PrEP is widely available and large-scale sensitization programs are ongoing, additional strategies are needed to dispel myths and address misconceptions held by community members that impede PrEP use among AGYW (Masyuko et al., 2018). A 2017 systematic review of PrEP use values and preferences in different populations identified high acceptance of PrEP, once participants were presented with more information about the drug; however, safety, side-effects, and effectiveness were barriers to use (Koechlin et al., 2017). These barriers were echoed by the participants in our FGDs.

In our study, community stakeholders reported that their community members perceived PrEP use among AGYW as either a result or a cause of risky behaviors. All participants felt that negative attitudes about PrEP were more common among those less familiar with PrEP. Importantly, participants recognized these attitudes as stigmatizing and felt that community-level stigma surrounding PrEP use was the primary reason that AGYW are reluctant to inquire about PrEP at health facilities and initiate use. This finding is consistent with other studies in which widespread stigma toward PrEP users was a prevailing concern among participants (Golub, 2018; Kambutse et al., 2018; Mack et al., 2014; Mack et al. 2015; Mullens et al., 2018; Van Der Straten et al., 2014; Wheelock et al., 2012). Community stakeholders in our study felt that the community was generally supportive of PrEP use among HIV serodiscordant couples and female sex workers (e.g., traditional high-risk groups), but that AGYW accessing PrEP are seen as misbehaving or “promiscuous.” Unpairing PrEP from traditional stigmatized high-risk groups and marketing PrEP as a health promotion intervention with benefits for AGYW could reduce behavior-related stigma and improve uptake.

Community stakeholders described how confusion around PrEP as an HIV prevention strategy versus ARVs for HIV treatment further fuels PrEP stigma. To move beyond this confusion, participants supported PrEP access points outside of HIV treatment clinics, either integrating PrEP within routine outpatient, MCH, or FP clinics, or moving delivery to the community. These PrEP delivery approaches could reduce HIV disease-related stigma and reach a broader population of AGYW. Community-based delivery strategies that promote universal access, rather than only targeting at-risk, often highly stigmatized groups, have been shown to be acceptable in other populations and could increase PrEP uptake among AGYW (Eakle et al., 2018). Additionally, securing the support of key opinion leaders could play a significant role in raising community awareness about PrEP and normalizing its use.

Participants also felt that judgment from HCWs experienced by AGYW was a key deterrent to PrEP use and should be systematically addressed by health care leadership. Previously, health system administrators in Kenya recognized the potential for HCWs to label PrEP clients as “promiscuous” and that HCWs’ negative attitudes toward high-risk groups indicated a need for targeted training of providers (Mack et al., 2015). Using standardized patient actors to evaluate HCW behavior and support HCW training in youth-friendly competencies may improve HCW interactions with AGYW (Mugo et al., 2019).

Our study has limitations. We sampled from a restricted pool of potential participants, reducing the generalizability of our results. However, prolonged engagement with the community through ongoing PrEP studies ensured that the themes we identified captured community views, and enabled us to gather rich information regarding community experiences, beliefs, and perceptions across several counties where programmatic PrEP delivery to AGYW is ongoing. In our study, CAB members were familiar with PrEP and convinced of its importance as an HIV prevention tool. This could influence their perceptions of community members who hold different beliefs about PrEP. Still, FGDs served as a platform for participants to voice their perceptions of community beliefs, and CAB members were selected to serve on CABs due to their knowledge of and status within their respective communities. Each FGD was comprised of participants from the same CAB; they had previously attended several CAB meetings and had developed a rapport with one another. PrIYA and PrIMA research coordinators did not perceive any potential power dynamics influencing FGD dialogue. Due to logistics of the study timeline, we were unable to perform member checking with CAB participants. However, CAB facilitators who were not directly involved with the data analysis reviewed our key findings as an external check.

Future PrEP scale-up for AGYW requires comprehensive understanding of implications within communities and health systems. PrEP demand creation should address misconceptions and stigma through extensive sensitization of target populations and the community in general. Meanwhile, alternative delivery approaches in health facilities and in the community can increase PrEP accessibility and acceptability. As AGYW continue to be at high risk for HIV acquisition, their involvement in policymaking, alongside key opinion leaders, will be critical for developing effective implementation strategies and improving understanding of PrEP among AGYW.

Key Considerations.

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) routinely access maternal and child health (MCH) and family planning (FP) clinics in HIV high-burden settings and could be reached with pre-exposure prophylaxis services within this context.

Community perspectives on integrating PrEP into MCH/FP could guide service delivery models, though few community-level data are available on PrEP delivery for AGYW.

Community members recommend training community health volunteers to deliver PrEP and involving AGYW in policymaking as ways to improve use among AGYW, by increasing accessibility and reducing stigma.

Acknowledgments:

This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD094630; MPI: Grace C. John-Stewart, Pamela Kohler). The PrEP Implementation for Mothers in Antenatal Care (PrIMA) Study is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI125498; MPI: Grace C. John-Stewart, Jared M. Baeten). The PrEP Implementation for Young Women and Adolescents (PrIYA) Program was funded by the United States Department of State as part of the DREAMS Innovation Challenge (Grant # 37188–1088 MOD01; MPI: Grace C. John-Stewart, Jared M. Baeten), managed by JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. The PrIYA Team was supported by the University of Washington’s Center for AIDS Research (CFAR; P30 AI027757; PI: Jared M. Baeten) and the Global Center for Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents, and Children (Global WACh). Jaclyn N. Escudero, Jillian Pintye, and Kristin M. Beima-Sofie wrote the manuscript. Grace C. John-Stewart, Jared M. Baeten, and Pamela Kohler were the principal investigators of this study and/or the parent study. Gabrielle O’Malley and Kristin M. Beima-Sofie conceived of and designed the qualitative component, including design of the interview guides. Jaclyn N. Escudero, Julia C. Dettinger, and Kristin M. Beima-Sofie analyzed the data. All authors reviewed and provided comments on the results and final manuscript. We would like to thank the Community Advisory Board members for their participation and contribution, and the PrEP Implementation for Young Women and Adolescents (PrIYA) Program for their support in conducting this study. We would also like to thank our qualitative interview team, including Merceline Awuor and Winnie Owade.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This work was funded by a grant from the United States Department of State as part of PEPFAR’s DREAMS Partnership, managed by John Snow, Inc (JSI) Research & Training Institute, Inc.. The opinions, findings, and conclusions stated herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State or JSI.

Conflict of Interest (COI): The authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jaclyn N. Escudero, Department of Global Health, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Julia C. Dettinger, Department of Global Health, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

Jillian Pintye, Department of Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Informatics, School of Nursing and Department of Global Health, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

John Kinuthia, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya..

Harison Lagat, University of Washington in Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya..

Felix Abuna, University of Washington in Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya..

Pamela Kohler, Department of Global Health, School of Public Health and Department of Child, Family, and Population Health Nursing, School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

Jared M. Baeten, Departments of Global Health and Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

Gabrielle O’Malley, Department of Global Health, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

Grace C. John-Stewart, Departments of Global Health and Epidemiology, School of Public Health, and Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

Kristin M. Beima-Sofie, Department of Global Health, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

References

- Attride-Stirling J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Community Partners. (2014). Recommendations for Community Engagement in HIV/AIDS Research. The Office of HIV/AIDS Network Coordination (HANC). https://www.hanc.info/cp/resources/Documents/Recommendations%202014%20FINAL%206-5-14%20rc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dettinger JC, Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Mwongeli N, Gómez L, Richardson BA, Barnabas R, Wagner AD, O’Malley G, Baeten JM, John-Stewart G. (2019). PrEP Implementation for Mothers in Antenatal Care (PrIMA): Study protocol of a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open, 9(3), e025122. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakle R, Bourne A, Mbogua J, Mutanha N, & Rees H. (2018). Exploring acceptability of oral PrEP prior to implementation among female sex workers in South Africa: Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21, e25081. 10.1002/jia2.25081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA (2018). PrEP stigma: Implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(2), 190–197. 10.1007/s11904-018-0385-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambutse I, Igiraneza G, & Ogbuagu O. (2018). Perceptions of HIV transmission and pre-exposure prophylaxis among health care workers and community members in Rwanda. Plos One, 13(11), e0207650. 10.1371/journal.pone.0207650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Abuna F, Lagat H, Mugwanya K, Dettinger J, Serede M, Sila J, Baeten JM, John-Stewart G. (2018, July 23–27). PrEP uptake among pregnant and postpartum women: results from a large implementation program within routine maternal child health (MCH) clinics in Kenya. 22nd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2018), Amsterdam, Netherlands. http://programme.aids2018.org/Abstract/Abstract/7484 [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin FM, Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, O’Reilly KR, Baggaley R, Grant RM, Rodolph M, Hodges-Mameletzis I, Kennedy CE (2017). Values and preferences on the use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among multiple populations: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1325–1335. 10.1007/s10461-016-1627-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack N, Odhiambo J, Wong CM, & Agot K. (2014). Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) eligibility screening and ongoing HIV testing among target populations in Bondo and Rarieda, Kenya: Results of a consultation with community stakeholders. BMC Health Services Research, 14:231. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack N, Wong C, McKenna K, Lemons A, Odhiambo J, & Agot K. (2015). Human resource challenges to integrating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into the public health system in Kenya: A qualitative study. African Journal of Reproductive Health March, 19(1), 54–62. 10.1111/epi.12912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuko S, Mukui I, Njathi O, Kimani M, Oluoch P, Wamicwe J, Mutegi J, Njogo S, Anyona M, Muchiri P, Maikweki L, Musyoki H, Bahati P, Kyongo J, Marwa T, Irungu E, Kiragu M, Kioko U, Ogando J, Were D, … Cherutich P. (2018). Pre-exposure prophylaxis rollout in a national public sector program: The Kenyan case study. Sexual Health, 15(6), 578–586. 10.1071/sh18090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health - Kenya. (2016). Guidelines on use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection in Kenya. https://www.prepwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Guidelines-on-ARV-for-Treating-Preventing-HIV-Infections-in-Kenya.pdf

- Mugo C, Wilson K, Wagner AD, Inwani IW, Means K, Bukusi D, Slyker J, John-Stewart G, Richardson BA, Nduati M, Moraa H, Wamalwa D. Kohler P. (2019). Pilot evaluation of a standardized patient actor training intervention to improve HIV care for adolescents and young adults in Kenya. AIDS Care, 31(10), 1250–1254. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1587361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugwanya K, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, Lagat H, Serede M, Sila J, John-Stewart J, Baeten JM (2018, July 23–27). Uptake of PrEP within clinics providing integrated family planning and PrEP services: results from a large implementation program in Kenya. 22nd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2018), Amsterdam, Netherlands. http://programme.aids2018.org/Abstract/Abstract/7467 [Google Scholar]

- Mugwanya K, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Lagat H, Abuna F, Begnel ER, Dettinger JC, John-Stewart G, Baeten J. (2019, March 4–7). Persistence with PrEP use in African adolescents and young women initiating PrEP. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2019), Seattle, Washington, USA.http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/persistence-prep-use-african-adolescents-and-young-women-initiating-prep [Google Scholar]

- Mullens AB, Kelly J, Debattista J, Phillips TM, Gu Z, & Siggins F. (2018). Exploring HIV risks, testing and prevention among sub-Saharan African community members in Australia. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12939-018-0772-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluoch LM, Roxby A, Wald A, Selke S, Margaret A, Micheni M, Chohan B, Ngure K, Gakuo S, Kiptinness C, Mugo N. (2019, March 4–7). Low uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among Kenyan adolescent girls at risk of HIV. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2019), Seattle, Washington, USA. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/low-uptake-preexposure-prophylaxis-among-kenyan-adolescent-girls-risk-hiv/ [Google Scholar]

- Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Roberts DA, Wagner AD, Mugwanya K, Abuna F, Lagat H, Owiti G, Levin C, Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, John-Stewart G. (2018). Integration of PrEP services into routine antenatal and postnatal care: Experiences from an implementation program in Western Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79(5), 590–595. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PrIYA Final Report. (2019). Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/uw.edu/priya

- Simoni JM, Beima-Sofie K, Amico KR, Hosek SG, Johnson MO, & Mensch BS (2019). Debrief reports to expedite the impact of qualitative research: Do they accurately capture data from in-depth interviews? AIDS and Behavior, 23(8), 2185–2189. 10.1007/s10461-018-02387-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. (2017a). Ending Aids Progress Towards the 90–90-90 Targets. Global Aids Update. https://doi.org/UNAIDS/JC2900E

- UNAIDS. (2017b). Start Free Stay Free AIDS Free 2017 progress report. https://doi.org/UNAIDS/JC2923Ehttps://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2923_SFSFAF_2017progressreport_en.pdf

- Van Der Straten A, Stadler J, Luecke E, Laborde N, Hartmann M, & Montgomery ET (2014). Perspectives on use of oral and vaginal antiretrovirals for HIV prevention: The VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(Suppl 2): 19146. 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock A, Eisingerich AB, Gomez GB, Gray E, Dybul MR, & Piot P. (2012). Views of policymakers, healthcare workers and NGOs on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): A multinational qualitative study. BMJ Open, 2(4), e001234. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]