Graphical abstract

Keywords: Nonenzymatic sensor, δ-MnO2, Ag NPs, H2O2, Ternary nanocomposite

Abstract

Cytotoxic H2O2 is an inevitable part of our life, even during this contemporary pandemic COVID-19. Personal protective equipment of the front line fighter against coronavirus could be sterilized easily by H2O2 for reuse. In this study, Ag doped δ-MnO2 nanorods supported graphene nanocomposite (denoted as Ag@δ-MnO2/G) was synthesized as a nonenzymatic electrochemical sensor for the sensitive detection of H2O2. The ternary nanocomposite has overcome the poor electrical conductivity of δ-MnO2 and also the severe aggregation of Ag NPs. Furthermore, δ-MnO2/G provided a rougher surface and large numbers of functional groups for doping more numbers of Ag atoms, which effectively modulate the electronic properties of the nanocomposite. As a result, electroactive surface area and electrical conductivity of Ag@δ-MnO2/G increased remarkably as well as excellent catalytic activity observed towards H2O2 reduction. The modified glassy carbon electrode exhibited fast amperometric response time (<2 s) in H2O2 determination. The limit of detection was calculated as 68 nM in the broad linear range (0.005–90.64 mM) with high sensitivity of 104.43 µA mM−1 cm−2. No significant interference, long-term stability, excellent reproducibility, satisfactory repeatability, practical applicability towards food samples and wastewater proved the efficiency of the proposed sensor.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is one of the most significant and versatile analytes available in our daily life [1], [2]. It is widely used as a disinfecting agent in food safety and medical care [1], [3], as a bleaching agent in the textile, wood, and paper industry [4], and as an oxidizing agent in environmental systems [5]. Recently, the Food and Drug Administration of the United States suggested sterilizing N95 respirator masks and personal protective equipment aerosolized by 35% concentrated vapor phase of H2O2 for the safety of doctors and their assistants during this contemporary pandemic COVID-19 [6]. On the other hand, H2O2 is also well known as a cytotoxic agent due to its reactive oxygen species (ROS) producing capability [7]. Excess secretions of ROS through abnormal production of H2O2 in the human body could damage cell components [1] and play a vital role in diseases mechanism [8]. So, H2O2 is highly responsible for some serious diseases such as cancer [9], inflammation [10], neurodegeneration [11], DNA damage [12], heart attack [1], Alzheimer’s [13], Parkinson’s [14], cardiovascular diseases [15], etc. Furthermore, H2O2 could easily contaminate the environment, it has adverse effects on the ecosystem also [16]. Though H2O2 is harmful to our health and environment, but we could not imagine a single day without it now a day. Because of significant applications of H2O2, an accurate, reliable, sensitive, rapid, and low-cost detection method developing is of great consideration [17]. Among several analytical detection methods of H2O2, electrochemical sensing is considered as the best technique because of its low cost, fast response, wide linear range, high sensitivity, better selectivity, low detection capability, and good reproducibility [18], [19], [20]. Owing to sluggish reaction kinetics, bare glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) provide a negligible current response towards H2O2 reduction [21]. Modification of GCE is necessary to enhance the large surface area to volume ratio, high conductivity, and fast response towards H2O2 [22]. Recently, non-enzymatic metal and metal oxide nanomaterials H2O2 sensors attracted much attention due to their low limit of detection, wide linear range, and long-term stability [3], [23].

Metal oxides are favorable for the synthesis of electrochemical sensors due to their chemical stability, good catalytic activity, outstanding ion exchange capability, and environmental compatibility [24]. Among various metal oxides, manganese oxide (MnO2) has been specifically chosen due to its non-toxicity, low cost, natural abundance and its better catalytic activity towards H2O2 [9], [25]. The different crystallographic polymorphs of MnO2 (α, β, γ, δ, λ, and ε) depend on the presence of fundamental [MnO6] octahedral units in its face, edge, and corner [24], [26]. Among them, δ-MnO2 demonstrates a two-dimensional (2D) layer-type structure with [MnO6] octahedral unit at the edge and provides the highest electrochemical performances due to its higher interlayer distance (∼7.0 A°) and largest tunnel size [26], [27]. The significant physicochemical characterizations of δ-MnO2 offer cation vacancies [27]. On the other hand, the poor electrical conductivity (10-5–10-6 S cm−1) of MnO2 is the main obstacle to its broad applications in electrochemical sensors [28]. This problem could be solved by loading MnO2 on highly conductive material such as graphene (G); which is one of the most remarkable substances in electrochemical sensors due to better electrical conductivity (550 S cm−1), excellent thermal conductivity (up to 5300 W m−1 K−1), large surface area (2630 m2 g−1), high charge carrier mobility (200,000 cm2 V−1 s), and a large number of electrochemically favorable carbon edges [3], [29].

The combination of δ-MnO2 and G provides a rougher surface and large numbers of functional groups for doping of heteroatoms, which could play an important role to facilitate electron transportation, increasing electron density, creating p- or n-junctions and tuning band gap [30], [31]. Doping of pure metal as a heteroatom on the defect surface of δ-MnO2/G can effectively modulate their physical and electronic properties and demonstrate the synergistic effect on the electrochemical performances [30]. A short number of metal doping reports are available for electrocatalysis due to its complex creation and tough acceptance [31]. Among different metal nanoparticles (NPs), silver NPs (Ag NPs) have been significantly reported as an effective H2O2 sensor due to large surface area, high conductivity, good biocompatibility, and low toxicity [1], [5], [18], [32], [33]. But Ag NPs suffer from severe aggregations because of the strong van der Waals force and high surface energy of nano-sized particles [5], [31]. The δ-MnO2/G surface could play a synergistic effect for the uniform distribution and effective size and shape of Ag NPs [31]. According to quantum chemical calculation, Mn doped can weaken the O—O bond and improve Ag catalysis performance, and Ag doped can enhance the adsorption of O2 by MnO2 [34].

Based on the above discussion, the limitations of δ-MnO2 could be exceeded by the combination of G. The prepared substrate (δ-MnO2/G) would be suitable for decreasing the aggregation of Ag NPs. And doping of Ag-atom on the defect surface of δ-MnO2/G will enhance their physical and electronic properties.

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis of Ag@δ-MnO2/G

In this study, we synthesized Ag doped δ-MnO2 nanorods (NRs) supported graphene nanocomposite (denoted as Ag@δ-MnO2/G) in a two-step facile route. In the first step, δ-MnO2 nanorods was synthesized in a simple hydrothermal process, and a perfectly oriented structure of δ-MnO2 (Scheme 1 b) was obtained. GO was obtained by modified Hummers’ method from graphite. In the second step, 30 mL of 5 mM AgNO3 aqueous solution was added into the as-prepared homogeneous solution of GO (30 mg) and δ-MnO2 (30 mg) slowly (1 mg mL−1), followed by the dropwise addition of 1% NaBH4 (450 µL). Then the mixture was refluxed at 110 °C for 6 h, after that kept under magnetic stirring for further 18 h at room temperature. The final product Ag@δ-MnO2/G was obtained after centrifugation several times with distilled water and ethanol, and drying at 60 °C for 72 h in a vacuum oven. In the second step, δ-MnO2 offer cation vacancies (Scheme 1c), and δ-MnO2/GO provided a rougher surface area and a large number of functional groups for absorption of heteroatom (i.e. Ag). When silver precursor was added, Ag ions were absorbed by electrostatic interaction into the δ-MnO2/GO and NaBH4 converted it to metallic Ag, which also convert GO to RGO. Subsequently, Ag atoms occupied the created vacancies of δ-MnO2, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G achieved higher structural benefits (Scheme 1d). Reagents, instrumental characterization and fabrication of working electrodes are discussed into the supporting information.

Scheme 1.

(a) basic structure of [MnO6] octahedral unit; schematic illustration of (b) perfectly oriented δ-MnO2 NRs, (c) δ-MnO2 NRs with Mn vacancies, and (d) δ-MnO2 NRs with Ag-doping.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Morphology analysis

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images demonstrated the surface morphology and defects of the as-prepared samples for analysis in Fig. 1 . Fig. S1a displayed nanorods (NRs) like morphology of δ-MnO2 on the graphene surface in δ-MnO2/G sample. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) of δ-MnO2/G revealed that the interlayer spacing of 0.69 nm, corresponding to the (0 0 1) plane of δ-MnO2 (Fig. S1b) [24], [35]. Fig. 1a illustrated homogeneous distribution of spherical Ag NPs on the graphene surface with average particle size of 11.18 ± 0.1 nm. HRTEM of Ag/G provided interlayer spacing of 0.24 nm, corresponding to the (1 1 1) lattice plane of pure Ag (Fig. S1c) [36]. Fig. 1b shows the TEM image of Ag@δ-MnO2/G, in which numerous number of Ag NPs are distributed on different lengths and diameters of δ-MnO2 decorated graphene surface. The average particle size of Ag NPs in Ag@δ-MnO2/G was calculated as 7.71 ± 0.1 nm. HRTEM of Ag@δ-MnO2/G exhibited the lattice d-spacing of 0.24 nm, and 0.69 nm corresponding to (1 1 1) plane of Ag, and (0 0 1) plane of δ-MnO2, respectively (Fig. 1c) [37]. It is notable that aggregation of Ag NPs was decreased in Ag@δ-MnO2/G than Ag/G. Furthermore, particle size of Ag NPs was smaller in Ag@δ-MnO2/G than Ag/G, which suggests the doping of Ag on δ-MnO2/G surface [34]. For the confirmation of doping of Ag on δ-MnO2/G surface, magnified HRTEM images were analyzed also. The magnified HRTEM image of Ag/G revealed uniformly distribute same size of dark spots without local lattice distortions indicates no impurity (Fig. 1d). Fig. 1e and 1f demonstrated the magnified HRTEM image of Ag@δ-MnO2/G in different regions. Fig. 1e exhibited clean areas due to the regular octahedral structure of δ-MnO2 NRs, also demonstrated dark spotted areas due to lattice disorder and dislocations of δ-MnO2 NRs [38], [39]. Fig. 1f exhibited thick and ink-like surface areas compared to Fig. 1e, which may be due to the doping of Ag atoms in cation vacancies of δ-MnO2 NRs [39], [40]. EDX spectrum revealed the successful synthesis of Ag@δ-MnO2/G (Fig. S1d). Furthermore, elemental mapping images of Ag@δ-MnO2/G portraying the uniform distribution of C, O, Mn, and Ag (Fig. S1(e-h)).

Fig. 1.

TEM images of (a) pure Ag/G, and (b) Ag@δ-MnO2/G; (c) HRTEM image of δ-MnO2 NRs and Ag NPs in Ag@δ-MnO2/G, corresponding magnified HRTEM images of (d) pure Ag/G, and (e and f) Ag@δ-MnO2/G in different regions.

3.2. Structural analysis

Fig. 2a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of RGO, δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G in 2θ = 10-90°. RGO contains an intense broad diffraction peak (0 0 2) and a small diffraction peak (1 0 0) of carbon at 2θ = 24.82° and 43.07°, respectively [41]. δ-MnO2/G demonstrated four diffraction peaks at 2θ = 12.31, 25.31, 36.75 and 65.61° corresponding to the (0 0 1), (0 0 2), (1 1 1) and (0 2 0), respectively, reflections of δ-MnO2 (JCDPS card No. 80–1098) [42], and a carbon peak (0 0 2) at 2θ = 24.71° (inset of Fig. 2a), reflection of graphene like structure. After deposition of Ag precursor, the resulted Ag@δ-MnO2/G illustrated five diffraction peaks at 2θ = 38.13, 44.39, 65.54, 77.44 and 81.71° corresponding to (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0), (3 1 1) and (2 2 2), reflections of face-centered cubic (fcc) phase of metallic Ag (JCDPS card No. 04–0783) [43]. The slightly positive shift of 2θ value and higher intensities of diffraction peaks of Ag@δ-MnO2/G compared to Ag/G (Fig. S2a), indicating the successful attachment of δ-MnO2 [43], [44]. There was no characteristic diffraction peak for RGO in Ag@δ-MnO2/G, due to quite uniform dispersion and more disorder stacking of RGO nanosheet [45].

Fig. 2.

(a) XRD patterns of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G, (b) Raman spectra of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G, (c) FTIR spectra of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G with GO as reference, and (d) UV–Vis spectra of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, Ag/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G; inset: the magnified XRD region of C(0 0 2) in δ-MnO2/G.

Fig. 2b exhibited the Raman spectrum of RGO, δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G. All samples demonstrated two characteristic D and G bands at ∼ 1349 and ∼ 1586 cm−1, respectively. The ID/IG ratios were obtained as 1.02, 1.06 and 1.08 for RGO, δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G, respectively. Representative peaks of δ-MnO2 (Fig. S2b) at 643 cm−1 and 504 cm−1 corresponding to symmetric stretching vibration of Mn-O of [MnO6], 565 cm−1 corresponding to symmetric stretching vibration of Mn-O in the basal plane of [MnO6], and 360 cm−1 corresponding to stretching vibrations of Mn-O-Mn in MnO2 [42], [46]. δ-MnO2/G contain a peak at 645 cm−1, which shifted to 613 cm−1 in Ag@δ-MnO2/G, confirm the presence of MnO2 in both samples. Ag@δ-MnO2/G displayed additional peak at 466, 843 and 1111 cm−1, due to presence of Ag in the nanocomposite [47].

Fig. 2c shows Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of the GO, RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@ δ-MnO2/G. FTIR spectrum of GO represents the characteristics peaks related to —OH (3000–3500 cm−1), C O (1733 cm−1), C C (1626 cm−1), C—OH (1405 cm−1), C—O—C (1227 cm−1), and C—O (1043 cm−1) [41], [48]. The intensities of all functional groups decreased dramatically in RGO, assured the successful reduction of GO. FTIR spectrum of δ-MnO2/G and Ag@ δ-MnO2/G contains two intense peaks at 489 and 604 cm−1 due to stretching vibrations of Mn-O, and one sharp peak at 1565 cm−1 due to bending vibration of Mn-OH [49], [50]. The –OH peak of δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G shifted to 3137 and 3029 cm−1, which confirm the presence of MnO2 surface [49]. Furthermore, the movement of –OH peak to lower wavelength and decrease of intensities in Mn-O of Ag@ δ-MnO2/G, compared to δ-MnO2/G, indicates the successful formation of Ag@ δ-MnO2/G.

Fig. 2d shows the UV–Vis spectra of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, Ag/G, and Ag@ δ-MnO2/G. RGO consists of a sharp π- π* absorption peak at 260 nm due to aromatic C-C bonds, and a shoulder n- π* absorption peak at 370 nm due to C = O bonds [51], [52]. δ-MnO2/G demonstrated a broad absorption peak at 350 nm due to δ-MnO2, and the characteristic absorption peak of RGO shifted slightly to 255 nm and absorption decreased dramatically [52], [53]. Ag/G displayed two well define absorption peaks at 260 nm and 400 nm due to RGO and Ag nanoparticles, respectively [54]. UV–Vis spectrum of Ag@δ-MnO2/G illustrated all absorption peaks of its synthesized materials and confirmed the successful formation. The absorption peaks at 275, 375 and 400 nm due to RGO, δ-MnO2 and Ag NPs, respectively.

Fig. 3a shows the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey spectrum of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G. RGO consists of two prominent signal peaks at 285.08 and 532.08 eV, due to the presence of carbon and oxygen, respectively, which confirmed the presence of graphene in all prepared samples [55]. δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G exhibited conjugated peaks in the range of 642.08–654.08 eV, which indicated the existence of Mn2p [56]. Furthermore, Ag@δ-MnO2/G displayed conjugated peaks in the range of 368.08–374.08 eV due to Ag3d, and additional two peaks at 573.08 eV and 604.08 eV due to Ag3p [43]. The C/O ratio was calculated as 2.50, 1.25, and 1.52 RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G, respectively. Following order of C/O ratio: RGO > Ag@δ-MnO2/G > δ-MnO2/G proved that Mn is in oxidized form in δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G [44], and degree of Mn oxidation is higher in Ag@δ-MnO2/G than that of δ-MnO2/G [43]. Fig. 3b shows the high-resolution C1s spectra of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G. C1s spectra of RGO was deconvoluted by four identical peaks at 284.58, 286.48, 288.18 and 290.48 eV corresponding to the C—C/C C, C—O—C, C O and O—C O, respectively. The slightly shift of peak positions in binding energy of δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G compared with RGO due to the strong electronic effect of carbon and metals [57]. The higher intensity of δ-MnO2/G at 286.58 eV compared to RGO, due to the abundance of C—O—C in δ-MnO2. Fig. S3 shows the high-resolution O1s spectra of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G. O1s spectra of RGO was deconvoluted by three identical peaks at 532.68, 533.68 and 534.48 eV corresponding to the C O, C—O, and O—C O, respectively. The slightly negative shift of peak position in binding energy of δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G than that of RGO due to the anchoring of positively charged Mn and negatively charged O, and an additional peak at 530.08 eV corresponding to metallic oxide [24]. Fig. 3c illustrated the Mn2p spectra of δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G. Mn2p spectra of δ-MnO2/G exhibited two peaks at 642.38 and 654.08 eV, corresponding to the Mn2p3/2 and Mn2p1/2 spins, respectively, with a typical spin energy separation of 11.7 eV. Whereas the spin energy separation between Mn2p3/2 and Mn2p1/2 was 11.5 eV in Ag@δ-MnO2/G, and this ∼ 0.2 eV lower indicates bimetallic alloy zone formation between δ-MnO2 and Ag in the Ag@δ-MnO2/G [58]. Fig. 3d shows the core-level Ag3d spectrum of Ag@δ-MnO2/G with two major peaks located at 368.28 and 374.28 eV for the Ag3d5/2 and Ag3d3/2 spins, respectively. The spin energy separation of 6.0 eV and no peaks for AgO and Ag2O, confirms the only presence of metallic Ag (Ag0) without any other silver oxide species [43].

Fig. 3.

(a) XPS survey spectra, and (b) core level spectra of C1s of RGO, δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G, (c) Mn2p survey spectra of δ-MnO2/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G, and (d) Ag3d spectrum of Ag@δ-MnO2/G.

3.3. Electrochemical performance of modified electrodes

The electroactive surface area (EASA) and electrical conductivity of the as-prepared samples were investigated by using 5.0 mM [Fe(CN)6]4-/3- in 0.05 M KCl. Fig. 4 a shows the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of bare glassy carbon electrode (GCE), δ-MnO2/G/GCE, Ag/G/GCE and Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 in Ar-saturated environment. All of the modified electrodes provided symmetric redox peaks, which indicated their charge transfer capability due to redox reactions. Among them Ag@δ-MnO2/G demonstrated highest redox peak currents and bare GCE demonstrated lowest redox peak currents. Ag/G/GCE showed higher redox peak currents than that of δ-MnO2/G/GCE, revealed that electron transfer ability of δ-MnO2/G/GCE is lower than Ag/G/GCE because of the presence of MnO2. Above statement implies that Ag NPs played an important role to enhance the facile electron transfer of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE. The EASA of different modified electrodes were calculated from the slope of the peak current (I p) versus the square root of the scan rate (ν 1/2) of different scan rates (40–400 mV s−1) (Fig. S4) by using the Randles–Sevcik equation [59]:

| (1) |

where the number of transferred electrons (n = 1), and diffusion coefficient (D = 7.60 × 10-6 cm2 s−1) for [Fe(CN)6]4-/3-, and concentration, C are constant parameters; so, the surface area (A) of the modified electrode is directly proportional to the peak current of the plot. The EASA was obtained as 0.1503 cm2, 0.1381 cm2, 0.0987 cm2, and 0.0707 cm2, for Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE, Ag/G/GCE, δ-MnO2/G/GCE, and bare GCE, respectively. About 8.14% and 34.33% higher EASA of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE than that of Ag/G/GCE and δ-MnO2/G/GCE, respectively, proved that Ag NPs modified the defective surface area of δ-MnO2 due to better absorption on δ-MnO2/G surface. The conductivity of bare GCE, δ-MnO2/G/GCE, Ag/G/GCE and Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE was monitored by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Fig. 4b displays the Nyquist plots of the modified electrodes. Bare GCE showed the bigger semicircle diameter than that of δ-MnO2/G/GCE, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE. Ag/G/GCE exhibited almost straight line like plot with smallest semicircle shape. The semicircle diameter was obtained as 1930.17 Ω, 1448.30 Ω, 691.97 Ω, and 317.39 Ω for bare GCE, δ-MnO2/G/GCE, Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE, Ag/G/GCE, respectively. Usually, conductivity decrease with the increase of semicircle diameter of modified electrodes. Here, Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE provided lower conductivity than that of Ag/G/GCE, which revealed that semiconductive MnO2 decreased the conductivity and Ag NPs played an important role to enhance the conductivity of the prepared samples. On the other hand, the conductivity of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE was significantly greater compared with δ-MnO2/G/GCE, which revealed that Ag NPs enhanced the conductivity of the proposed sample [60].

Fig. 4.

(a) CV curves at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 and (b) Nyquist plots at a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 KHz of bare GCE, δ-MnO2/G, Ag/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G in 0.05 M KCl with 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]4-/3-.

3.4. Electrochemical behaviors of H2O2 on fabricated electrodes

Fig. 5 shows the CV curves of different modified electrodes towards 2.0 mM H2O2 at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0). Fig. 5a demonstrated the several cycles of bare GCE sweeping from −2.0 to 2.0 V. First cycle of the figure displayed a reduction peak at −0.546 V and no oxidation peak, which indicated a chemically irreversible reduction process. When H2O2 introduced in the PBS solution, the reduction mechanism followed the following reactions [61]:

| H2O2 + e- ↔ OH(ads) + OH– | (2) |

| OH(ads) + e- ↔ OH– | (3) |

| OH– + 2H+ ↔ 2H2O | (4) |

Fig. 5.

CV curves of (a) bare GCE in 2.0 mM H2O2 (4 cycles), (b) Ag@δ-MnO2/G in absence and presence of 2.0 mM H2O2, (c) comparison of bare GCE, δ-MnO2/G, Ag/G, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G in presence of 2.0 mM H2O2, and (d) different concentrations of Ag@δ-MnO2/G (0 to 12 mM) in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0) at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1; insets: (a) magnified reduction and oxidation peaks, and (d) plot of current vs. [H2O2]. Error bars set for 5% of standard error.

With the increment of cycles, the reduction peak shifted to lower potential and peak current increased. On the other hand, after third cycle, there was a tiny oxidation peak due to the saturation of H2O2 [62].

Fig. 5b illustrated the electrochemical performance of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE in absence and presence of 2.0 mM H2O2. In which there was no electrochemical response in absence of H2O2, and provided a remarkable reduction peak at −0.528 V after addition of 2.0 mM H2O2 following the irreversible reactions:

| H2O2 → ½ O2 + H2O | (5) |

| O2 + 2e- + 2H+ → H2O2 | (6) |

Similarly, bare GCE, δ-MnO2/G/GCE, and Ag/G/GCE showed reduction peak towards H2O2, whereas there was no peak in absence of H2O2. (Fig. S5). Fig. 5c exhibited CV comparison of bare GCE, δ-MnO2/G/GCE, Ag/G/GCE, and Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE. The catalytic current density of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE was about 77% greater than δ-MnO2/G/GCE, which indicated the synergistic effect of Ag NPs on the defective surface of δ-MnO2/G. Furthermore, about 32% greater current density and 60 mV positive shift of reduction peak potential of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE than Ag/G/GCE, proved that the δ-MnO2 enhanced the electrochemical performances of the modified electrodes towards H2O2 [60]. Fig. 5d demonstrated the effect of concentration on Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE from 0 to 12 mM H2O2 at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0). There was no characteristic peak in absence of H2O2. When H2O2 was introduced in PBS solution, due to catalytic current response (Ipc) a peak was appeared. The reduction peak increased gradually and peak potential shifted negatively with the increment of [H2O2], which indicated the effective electrocatalytic activity of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE towards H2O2. The plot of Ipc versus [H2O2] from 1 to 10 mM provided a linear regression equation: Ipc (µA) = 20.81[H2O2] (mM) + 19.748, R2 = 0.9902 (Fig. 5d inset); which confirmed the direct electro-reduction of H2O2 on the surface of Ag@δ-MnO2/G nanocomposite. where R2 is the correlation coefficient. Similarly, in the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) curves, the reduction peaks current increased and the peak potential shifted negatively with the increment of [H2O2] from 0 to 10 mM (Fig. S6) according to the following linear fit: Ipc (µA) = 6.1679[H2O2] (mM) + 1.0251, R2 = 0.9945 [100 µM to 10 mM] (inset).

3.5. Kinetic behaviors of Ag@δ-MnO2/G electrode

Fig. 6a showed the influence of different pH (5.0 to 9.0) of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE towards 2.0 mM H2O2 at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 in 0.2 M PBS. Fig. 6b illustrated the plot of catalytic current (Ipc) versus pH, and the plot of reduction potential (Epc) versus pH. The plot of Epc versus pH showed that peak potential decreased with the increased of pH, which indicated the active participation of protons in the electrochemical reaction [63]. The slope of Epc versus pH was obtained as −61.4 mV/pH, which matched with the equation (6) for two-electron and two proton process [64]. From the plot of Ipc versus pH the highest peak current was observed at pH 7.0, therefore pH 7.0 was selected for the further experiment of this study.

Fig. 6.

(a) CV curves of Ag@δ-MnO2/G at different pH (5.0 to 9.0) in the presence of 2.0 mM H2O2 in 0.2 M PBS at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. (b) Peak potential and peak current as the function of pH. Error bars set for 5% of standard error.

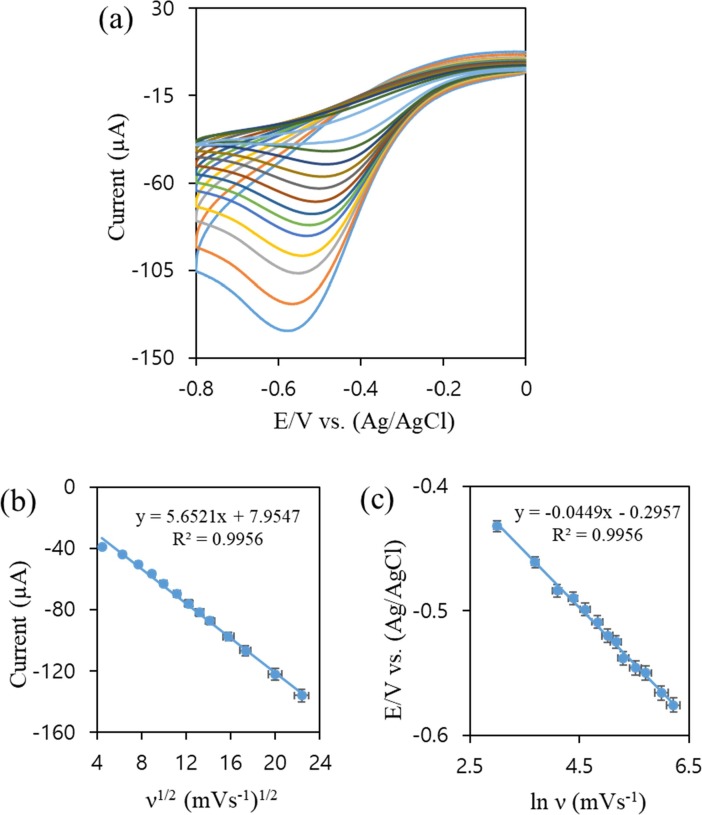

Fig. 7a illustrated the effect of different scan rates (20 to 500 mV s−1) of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE towards 2.0 mM H2O2 in 0.2 M PBS. The catalytic current increased with the increase of scan rate. Fig. 7b demonstrated that the plot of Ipc versus square root of scan rate (ν1/2) provided a linear regression equation: Ipc (µA) = 5.6521 ν1/2 + 7.9547, R2 = 0.9956; which indicated that diffusion controlled reduction reaction between Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE and H2O2 [39]. Furthermore, Epc versus ln ν (Fig. 7c) also provided a linear regression equation: Epc (V) = -0.0449 ln ν − 0.2957, R2 = 0.9956; which confirmed that the electron transfers kinetics of H2O2 remained unchanged in wide range of scan rates at the surface of Ag@δ-MnO2/G [65].

Fig. 7.

(a) CV curves of Ag@δ-MnO2/G at different scan rates (20 to 500 mV/s) in presence of 2.0 mM H2O2 in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0). (b) Linear dependence of the peak current with the square root of the scan rate (ν1/2), and (c) linear relation between the peak potential and lnν. Error bars set for 5% of standard error.

3.6. Quantitative determination of H2O2 at δ-MnO2/G and Ag@δ-MnO2/G

Fig. 8a demonstrated the choronoamperometric (CA) current–time curve of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE and δ-MnO2/G/GCE at −0.5 V for successive addition of H2O2 in every 50 s into stirred 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0). When there was no H2O2 in the system, none of modified electrodes showed any current response. At 50 s, when trace quantity of H2O2 was added, both of them showed almost equal current response. But after 150 s, Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE showed much higher catalytic current response than δ-MnO2/G/GCE for each addition of H2O2. Fig. S6 implied that Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE reached to a steady-state current within 2 s, whereas δ-MnO2/G/GCE took around 5 s (Fig. S7). The faster and remarkable current response of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE compared with δ-MnO2/G/GCE, ascribed that Ag NPs significantly improved the EASA of the defective surface of δ-MnO2/G as well as surface/interface properties. The sharp electrochemical response of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE was observed due to fast adsorption, diffusion and electron transfer capacity of the modified electrode towards H2O2. Fig. 8b showed that the plot of Ipc versus [H2O2] of δ-MnO2/G/GCE provided two linear regression equations as below:

Fig. 8.

(a) CA current response of Ag@δ-MnO2/G and δ-MnO2/G at an applied potential of −0.5 V with successive additions of H2O2 in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0), relationship between current vs. [H2O2] for (b)δ-MnO2/G (50 μM to 16 mM), and (c) Ag@δ-MnO2/G (5 μM to 90.64 mM); inset: magnified CA curves of Ag@δ-MnO2/G at lower concentration. Error bars set for 5% of standard error.

Ipc (µA) = 2.4601 [H2O2] (mM) + 2.2791, R2 = 0.9932; [0.05 to 4.0 mM].

and,

Ipc (µA) = 0.08408 [H2O2] (mM) + 8.0802, R2 = 0.9924; [ 4.0 to 16.0 mM].

The limit of detection (LOD) and sensitivity of δ-MnO2/G was obtained as 0.756 µM and 34.79 µA mM−1 cm−2 (0.05 to 4.0 mM), and 2.46 µM and 11.89 µA mM−1 cm−2 (4.0 to 16.0 mM), respectively (where, S/N = 3). Fig. 8c showed that the plot of Ipc versus [H2O2] of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE provided a linear regression equation as below:

Ipc (µA) = 7.3829 [H2O2] (mM) + 5.3533, R2 = 0.9987; [ 0.005 to 90.64 mM].

The LOD and sensitivity of Ag@δ-MnO2/G was obtained as 0.068 µM and 104.43 µA mM−1 cm−2, respectively (where, S/N = 3). Table 1 . and Table 2 . represent the comparison in electrochemical parameters of Ag@δ-MnO2/G with other previously reported non-Ag and Ag modified sensors for H2O2 determination, which implied the proposed modified electrode as one of the best sensors.

Table 1.

Comparison of the detection parameters of Ag@δ-MnO2/G with the previously reported non-Ag catalysts for determination of H2O2.

| Sensors | Response time (s) | Linear range (mM) | Sensitivity (µA mM−1 cm−2) | Detection limit (µM) | Refs[published year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE | <2 | 0.005–90.64 | 104.43 | 0.068 | This work |

| TS-HTC/GCE | 3.61 | 0.05–0.5 | 122.02 | 0.015 | [7][2021] |

| 0.5–2.7 | 80.79 | 0.05 | |||

| NCNT MOF CoCu | <3 | 0.0–3.5 | 639.5 | 0.206 | [23][2021] |

| MnFe2O4/rGO/SPCE | ∼5 | 0.1–4.0 | 6.337* | 0.528 nM | [25][2021] |

| MnO2-SWCNTs/GCE | <10 | 0.015–2.0 | – | 1.0 | [9][2020] |

| GN@FeOOH | ∼3 | 0.0003–1.2 | 265.7 | 0.08 | [12][2020] |

| CuCo2O4 | <3 | 0.01–8.90 | 94.1 | 3.0 | [66][2020] |

| CC/Co@C-CNTs | <4 | 0.0004–7.2 | 388 | 0.27 | [67][2020] |

| MnO2(δ)/MWCNT | <2 | 0.100–20.5 | 13.9 | 6.97 | [68][2019] |

| Mn(II)-PLH-CMWCNT/GCE | <3 | 0.002–1.0 | 464.18 | 0.5 | [69][2019] |

| δ-MnO2/CNTs/GCE | <3 | 0.05–22.0 | 243.9 | 1 | [24][2016] |

μA mM−1.

Table 2.

Comparison of the detection parameters of Ag@δ-MnO2/G with the previously reported Ag catalysts for determination of H2O2.

| Sensors | Response time (s) | Linear range (mM) | Sensitivity (µA mM−1 cm−2) | Detection limit (µM) | Refs[published year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE | <2 | 0.005–90.64 | 104.43 | 0.068 | This work |

| LIG@Ag | ∼3 | 0.01–2.61 | 28.6 | 2.8 | [1][2021] |

| HPCS-Ag | <3 | 0.004–0.24 | 637 | 0.188 | [5][2021] |

| Crod@Ag-Ps | – | 0.5–5.0 | 128 | 67.0 | [18][2021] |

| Ag–Pt core–shell NWs | 4.74 | 0.017–0.99 | – | 10.95 | [19][2021] |

| Ag-Fe2O3/POM/ RGO | <5 | 0.3–3.3 | 271 | 0.2 | [20][2020] |

| AgNWs0.5/GCE | <5 | 0.001–1.075 | – | 0.05 | [32][2020] |

| Ag/H-ZIF-67/GCE | 1.5 | 0.005–67 | 421.4 | 1.1 | [33][2020] |

| PDDA-AuPtAg/RGO | <5 | 0.00005–5.5 | 2838.95 | 0.0012 | [70][2019] |

| Nf/Pd@Ag/rGO-NH2/GCE | <2 | 0.002–19.5 | 1307.46 | 0.7 | [71][2018] |

| Ag/MnO2/GO/GCE | <5 | 0.003–7 | 105.40 | 0.7 | [31][2015] |

| Ag-MnO2-MWCNTs/GCE | <2 | 0.005–10.4 | 82.5 | 1.7 | [59][2013] |

3.7. Interference study

Fig. 9a exhibited the interference effect of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE towards 750 μM H2O2 in presence of 750 μM coexist biomolecules such as ascorbic acid (AA), glucose (Glu), acetaminophen (AP), uric acid (UA), dopamine (DA), 10-fold excess of ethanol (EtOH), and 25-fold excess of common ions such as Na+, Mn2+, I-, and CO3 2– in Ar-saturated 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0) at −0.5 V. None of them showed significant current response, whereas H2O2 brought out well defined current response for every successive addition. Each of the successive addition of 750 μM H2O2 provided almost equal current response, interestingly third addition was slight higher than that of second one (Fig. 9a, inset). Fig. 9b showed the CA difference between the Ar and O2-saturated 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0) at −0.5 V for successive addition of 750 μM H2O2 at every 100 s. Ar-saturated CA provided smooth and stable current response along with good signal-to-noise ratio, whereas background noise in O2-saturation increased with time due to electro-reduction of oxygen.

Fig. 9.

CA current response of the Ag@δ-MnO2/G towards 750 μM H2O2 (a) in presence of 750 μM AA, Glu, AP, UA, DA, 10-fold excess of EtOH, and 25-fold excess of Na+, CO32–, Mn2+, and I- in Ar-saturated 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0), and (b) comparison between O2-saturated and Ar-saturated system at −0.5 V.

3.8. Long-term stability, reproducibility and repeatability

The stability, reproducibility and repeatability of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE towards 2.0 mM H2O2 were investigated by CV at a scan rate of 50 mV/s in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0). The stability of the modified electrode was checked every three days during a period of 30 days while the modified electrode was at room temperature under a plastic cover. After one month 87.54% relative current of initial current was obtained (Fig. S8a), which indicated the long-term stability of the modified electrode. Electrode-to-electrode reproducibility was evaluated by six different electrodes (Fig. S8b) and the relative standard deviation (RSD) was calculated as 1.19%. Repeatability was examined by ten consecutive measurements of same electrode and RSD was calculated as 4.34%.

3.9. Real samples analysis

The practical application of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE towards different concentration of H2O2 was investigated by DPV (Fig. S9) in food samples (honey, milk and tomato sauce (TS)) and industrial sample (tab water (TW)) in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0). Honey, liquid milk and TS were collected from local supermarket of Gwangju, South Korea. All of the food samples centrifuged and diluted in distilled water for homogeneous solution, and reserved in refrigerator before used. TW was taken from our lab basin and used without any purification. 50 µL of each sample was added in 3950 µL 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.0) individually for the preparation of real samples. Then 0.10, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mM H2O2 was added subsequently in those samples, and obtained current was measured. The founded concentration was calculated from the obtained current for each real samples (Fig. S9 insets). The result of practicability was summarized in Table 3 . The recovery ranges and relative standard deviation (RSD) of all the real samples indicated that the sensor was effective for the practical applications.

Table 3.

Determination result of H2O2 in food and wastewater samples at Ag@δ-MnO2/G.

| Samples | Added H2O2 (mM) | Founded H2O2 (mM) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honey | 1.0 0.50 0.25 0.10 |

1.027 0.506 0.252 0.098 |

102.7 101.2 100.8 98.0 |

1.69 |

| Milk | 1.0 0.50 0.25 0.10 |

1.031 0.509 0.244 0.099 |

103.1 101.8 97.6 99.0 |

1.12 |

| Tomato sauce (TS) | 1.0 0.50 0.25 0.10 |

1.009 0.492 0.251 0.103 |

100.9 98.4 100.4 103.0 |

1.63 |

| Tab water (TW) | 1.0 0.50 0.25 0.10 |

0.993 0.513 0.249 0.097 |

99.3 102.6 99.6 97.0 |

1.99 |

4. Conclusion

The Ag@δ-MnO2/G ternary nanocomposite was synthesized to increase the electrical conductivity of δ-MnO2 and reduce the aggregation of Ag NPs. Furthermore, we have planned to occupy the cation vacancies of δ-MnO2 by the Ag-atom for achieve a better electronic structure and surface/interface properties. TEM images revealed that Ag atom was successfully doped on MnO2/G surface. The defective bimetallic zone created by Ag atom in the prepared sample provided higher electrochemical performances. As a result, Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE exhibited a faster and remarkable current response towards H2O2 compared with δ-MnO2/G/GCE in CA. The LOD, sensitivity, linear range, and response time of Ag@δ-MnO2/G/GCE were better than δ-MnO2/G/GCE. The proposed sensor also showed negligible interference, long-term stability, repeatability, reproducibility, and excellent practicability in food and industrial samples.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdul Kader Mohiuddin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Seungwon Jeon: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF-2021R1F1A1047229).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153162.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhao G., Wang F., Zhang Y., Sui Y., Liu P., Zhang Z., Xu C., Yang C. High-performance hydrogen peroxide micro-sensors based on laser-induced fabrication of graphene@Ag electrodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021;565 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitnikova N.A., Borisova A.V., Komkova M.A., Karyakin A.A. Superstable advanced hydrogen peroxide transducer based on transition metal hexacyanoferrates. Anal. Chem. 2011;83(6):2359–2363. doi: 10.1021/ac1033352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L., Deng M., Ding G., Chen S., Xu F. Manganese dioxide based ternary nanocomposite for catalytic reduction and nonenzymatic sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;114:416–423. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westbroek P., Kiekens P. Electrochemical behavior of hydrogen peroxide oxidation: kinetics and mechanism. Anal. Electrochem. Textiles. 2005;4:92–132. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X., Lu K., Tang K., Zhao W. Construction of electrocatalyst based on in-situ growth silver nanoparticles into hollow porous carbon spheres for hydrogen peroxide detection. Microchem. J. 2021;170 [Google Scholar]

- 6.G. Mccormick, New decontamination protocol permits reuse of N95 respirators, 22 April, 2020, Penn State News.

- 7.Guo X., Liang T., Yuan C., Wang J. Expanding horizon: controllable morphology design of an ecofriendly tamarind seedcase-derived porous carbonaceous biomass as a versatile electrochemical biosensor platform for reactive oxygen species. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:765–775. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abo M., Urano Y., Hanaoka K., Terai T., Komatsu T., Nagano T. Development of a highly sensitive fluorescence probe for hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(27):10629–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja203521e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Z.-N., Zou J., Yu J.-G. Facile and rapid Fabrication of petal-like hierarchical MnO2 anchored SWCNTs composite and its application in amperometric detection of hydrogen peroxide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020;167 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmström K.M., Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signaling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrm3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon S.J., Stockwell B.R. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10(1):9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X., Gao J., Zhao G., Wu C. Can, In situ growth of FeOOH nanoparticles on physically-exfoliated graphene nanosheets as high performance H2O2 electrochemical sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020;313 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez Del Rio M., Velez-Pardo C. The hydrogen peroxide and its importance in Alzheimers and Parkinsons disease. Cent. Nerv. Sys. Agents Med. Chem. 2004;4:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T.Y., Leem E., Lee J.M., Kim S.R. Control of reactive oxygen species for the prevention of Parkinson’s disease: the possible application of flavonoids. Antioxidants. 2020;9:583. doi: 10.3390/antiox9070583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinhorn B., Sorrentino A., Badole S., Bogdanova Y., Belousov V., Michel T. Chemogenetic generation of hydrogen peroxide in the heart induces severe cardiac dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06533-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin L., Shan K., Xiong Q., Zhou Q., Li L., Gan N., Song L. The ecological risks of hydrogen peroxide as a cyanocide: its effect on the community structure of bacterioplankton. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2018;36(6):2231–2242. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian J., Liu Q., Ge C., Xing Z., Al-Youbi A.M.A.O., Sun X. Ultrathin graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets: a low-cost, green, and highly efficient electrocatalyst toward the reduction of hydrogen peroxide and its glucose biosensing application. Nanoscale. 2013;5:8921. doi: 10.1039/c3nr02031b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brzozka A., Brudzisz A., JeleÅ A., Kozak M., Wesot J., Iwaniec M., Sulka G.D. A comparative study of electrocatalytic reduction of hydrogen peroxide at carbon rod electrodes decorated with silver particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2021;263 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koylan S., Tunca S., Polat G., Durukan M.B., Kim D., Kalay Y.E., Ko S.H., Unalan H.E. Highly stable silver–platinum core–shell nanowires for H2O2 detection. Nanoscale. 2021;13(30):13129–13141. doi: 10.1039/d1nr01976g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross N., Civilized Nqakala N. Electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide by a nonenzymatic catalytically enhanced silver-iron (III) oxide/polyoxometalate/reduced graphene oxide modified glassy carbon electrode. Anal. Lett. 2020;53(15):2445–2464. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baghayeri M., Zare E.N., Lakouraj M.M. Monitoring of hydrogen peroxide using a glassy carbon electrode modified with hemoglobin and a polypyrrole-based nanocomposite. Microchim. Acta. 2015;182(3-4):771–779. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z., Leung C., Gao F., Gu Z. Effects of nanowire length and surface roughness on the electrochemical sensor properties of nafion-free, vertically aligned Pt nanowire array electrodes. Sensors. 2015;15:22473–22489. doi: 10.3390/s150922473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S.E., Muthurasu A. Highly oriented nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube integrated bimetallic cobalt copper organic framework for non-enzymatic electrochemical glucose and hydrogen peroxide sensor. Electroanalysis. 2021;33(5):1333–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begum H., Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. A novel δ-MnO2 with carbon nanotubes nanocomposites as an enzyme-free sensor for hydrogen peroxide electrosensing. RSC Adv. 2016;6:50572. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X., Li Z., Chen C., Xie L., Zhu Z., Zhao H., Lan M. MnFe2O4 nanoparticles-decorated graphene nanosheets used as an efficient peroxidase minic enable the electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide with a low detection limit. Microchem. J. 2021;166 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen T., Zhou Y., Zhang J., Cao Y. Two-dimensional MnO2/reduced graphene oxide nanosheet as a high-capacity and high-rate cathode for Lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018;13(2018):8575–8588. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rong S., Li K., Zhang P., Liu F., Zhang J. Potassium associated manganese vacancy in birnessite-type manganese dioxide for airborne formaldehyde oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018;8(7):1799–1812. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.-H., Hong H.-G. Nonenzymatic electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide based on a polyaniline-MnO2 nanofiber-modified glassy carbon electrode. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2015;45:1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasmin S., Ahmed M.S., Park D., Jeon S. Nitrogen-doped graphene supported cobalt oxide for sensitive determination of dopamine in presence of high level ascorbic acid. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016;163(9):B491–B498. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H., Zhang J., Hang X., Zhang X., Xie J., Pan B., Xie Y.i. Half-metallicity in single-layered manganese dioxide nanosheets by defect engineering. Angew. Chem. 2015;127(4):1211–1215. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J., Rao D., Zheng J. Synthesis of Ag nanoparticle doped MnO2/GO nanocomposites at a gas/liquid interface and its application in H2O2 detection. Electroanal. 2016;28(3):588–595. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Rahim R.D., Emran M.Y., Naguib A.M., Farghaly O.A., Taher M.A. Silver nanowire size-dependent effect on the catalytic activity and potential sensing of H2O2. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2020;1 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun D., Yang D., Wei P., Liu B., Chen Z., Zhang L., Lu J. One-step electrodeposition of silver nanostructures on 2D/3D metal-organic framework ZIF-67: comparison and application in electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:41960–41968. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c11269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H., Hu Z., Yao C., Yu J., Du Z. Silver doped amorphous MnO2 as electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction in Al-Air battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020;167 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfaruqi M.H., Gim J., Kim S., Song J., Pham D.T., Jo J., Xiu Z., Mathew V., Kim J. A layered δ-MnO2 nanoflake cathode with high zinc-storage capacities for eco-friendly battery applications. Electrochem. Commun. 2015;60:121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta S., Ray C., Sarkar S., Pradhan M., Negishi Y., Pal T. Silver nanoparticle decorated reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanosheet: A platform for SERS based low-level detection of uranyl ion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:8724–8732. doi: 10.1021/am4025017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao W., Wang J., Li H., Lu Y., Yun Flexible α-MnO2 paper formed by millimeter-long nanowires for supercapacitor electrodes. J. Power Sources. 2014;247(2014):824–830. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren Y., Ma Z., Morris R.E., Liu Z., Jiao F., Dai S., Bruce P.G. A solid with a hierarchical tetramodal micro-meso-macro pore size distribution. Nat. Commun. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohiuddin A.K., Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. Palladium doped α-MnO2 nanorods on graphene as an electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of dopamine and paracetamol. App. Surf. Sci. 2022;578 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo C., Wang C., Wu X., Zhang J., Chu J. In situ transmission electron microscopy characterization and manipulation of two-dimensional layered materials beyond graphene. Small. 2017;13:1604259. doi: 10.1002/smll.201604259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar A., Sundaram A.M., Jain S.L. Silver doped reduced graphene oxide as promising plasmonic photocatalyst for oxidative coupling of benzylamines under visible light irradiation. New J. Chem. 2019;43:9116–9122. [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Oliveria Cremonezzi J.M., Tiba D.Y., Domingues S.H. Fast synthesis of δ-MnO2 for a high-performance supercapacitor electrode, SN. Appl. Sci. 2020;2:1689. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee K., Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. Electrochemical deposition of silver on manganese dioxide coated reduced graphene oxide for enhanced oxygen reduction reaction. J. Power Sources. 2015;288:261–269. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. Highly active graphene-supported NixPd100-x binary alloyed catalysts for electro-oxidation of ethanol in an alkaline media. ACS Catal. 2014;4:1830–1837. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H., Zhang J., Zhang B., Shi L., Tan S., Huang L. Nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide-Ni(OH)2-built 3D flower composite with easy hydrothermal process and excellent electrochemical performance. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;138:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang L., Lei H., Liu H., Ruan Y., Su R., Hu L., Tian Z., Hu J. Li, Fabrication of β-MnO2/RGO composite and its electrochemical properties. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016;11:10815–10826. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naqvi T.K., Srivastava A.K., Kulkarni M.M., Siddiqui A.M., Dwivedi P.K. Silver nanoparticles decorated reduced graphene oxide (rGO) SERS sensor for multiple analytes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;478:887–895. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faniyi I.O., Fasakin O., Olofinjana B., Adekunle A.S., Oluwasusi T.V., Eleruja M.A., Ajayi E.O.B. The comparative analyses of reduced graphene oxide (RGO) prepared via green, mild and chemical approaches. SN Appl. Sci. 2019;1:1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang X., Hu N., Gao R., Yu Y., Wang Y., Yang Z., Kong E.-S.-W., Wei H., Zhang Y. Reduced graphene oxide–polyaniline hybrid: Preparation, characterization and its applications for ammonia gas sensing. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:22488. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H., He Y., Pavlinek V., Cheng Q., Saha P., Li C. MnO2 nanoflake/polyaniline nanorod hybrid nanostructures on graphene paper for high-performance flexible supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3(33):17165–17171. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang S., Yue W., Huang D., Chen C., Lin H., Yang X. A facile green strategy for rapid reduction of graphene oxide by metallic zinc. RSC Adv. 2012;2:8827. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar A., Aathira M.S., Pal U., Jain S.L. Photochemical oxidative coupling of 2-naphthols using hybrid rGO/MnO2 nanocomposite under visible light irradiation. ChemCatChem. 2018;10:1844–1852. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roy H.S., Mollah M.Y.A., Islam M.M., Susan M.A.B.H. Poly(vinyl alcohol)–MnO2 nanocomposite films as UV-shielding materials. Polym. 2018;75:5629–5643. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pusty M., Rana A.K., Kumar Y., Sathe V., Sen S., Shirage P. Synthesis of partially reduced graphene oxide/silver nanocomposite and its inhibitive action on pathogenic fungi grown under ambient conditions. ChemistrySelect. 2016;1(14):4235–4245. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. Electrochemical activity evolution of chemically damaged carbon nanotube with palladium nanoparticles for ethanol oxidation. J. Power Sources. 2015;282:479–488. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Begum H., Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. δ-MnO2 nanoflowers on sulfonated graphene sheets for stable oxygen reduction and hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta. 2019;296:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 57.He Q., Ji J., Zhang Q., Yang X., Lin Y., Meng Q., Zhang Y., Xu M. PdMn and PdFe nanoparticles over a reduced graphene oxide carrier for methanol electro-oxidation under alkaline conditions. Kiel. 2020;26:2421–2433. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma C.S., Awasthi R., Singh R.N., Sinha A.S.K. Graphene-manganite-Pd hybrids as highly active and stable electrocatalysts for methanol oxidation and oxygen reduction. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;136:166–175. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohiuddin A.K., Ahmed M.S., Roy N., Jeon S. Electrochemical determination of hydrazine in surface water on Co(OH)2 nanoparticles immobilized on functionalized graphene interface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;540 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han Y., Zheng J., Dong S. A novel nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based Ag-MnO2-MWCNTs nanocomposites. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;90:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai X., Tanner E.E.L., Lin C., Ngamchuea K., Foord J.S., Compton R.G. The mechanism of electrochemical reduction of hydrogen peroxide on silver nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20(3):1608–1614. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07492a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y., Huang X., Chen Y., Wang L., Lin X. Simultaneous determination of dopamine and serotonin by use of covalent modification of 5-hydroxytryptophan on glassy carbon electrode. Microchim. Acta. 2009;164(1-2):107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ensafi A.A., Abarghoui M.M., Rezaei B. Electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide using copper/porous silicon based non-enzymatic sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014;196:398–405. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neumann C.C.M., Laborda E., Tschulik K., Ward K.R., Compton R.G. Performance of silver nanoparticles in the catalysis of the oxygen reduction reaction in neutral media: Efficiency limitation due to hydrogen peroxide escape. Nano Res. 2013;6:511–524. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sandford C., Edwards M.A., Klunder K.J., Hickey D.P., Li M., Barman K., Sigman M.S., White H.S., Minteer S.D. A Synthetic Chemist’s Guide to Electroanalytical Tools for Studying Reaction Mechanisms. Chem. Sci. 2019;10(26):6404–6422. doi: 10.1039/c9sc01545k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng D.i., Wang T., Zhang G., Wu H., Mei H.e. A novel nonenzymatic electrochemical sensor based on double-shelled CuCo2O4 hollow microspheres for glucose and H2O2. J. Alloys Compd. 2020;819 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Long L., Liu H., Liu X., Chen L., Wang S., Liu C., Dong S., Jia J. Co-embedded N-doped hierarchical carbon arrays with boosting electrocatalytic activity for in situ electrochemical detection of H2O2. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020;318 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dinesh M., Revathi C., Haldorai Y., Thangavelu Rajendra Kumar R. Birnessite MnO2 decorated MWCNTs composite as a nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019;731 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou J., Chen Y., Lan L., Zhang C., Pan M., Wang Y., Han B., Wang Z., Jiao J., Chen Q. A novel catalase mimicking nanocomposite of Mn(II)-poly-L-histidine-carboxylated multi walled carbon nanotubes and the application to hydrogen peroxide sensing. Anal. Biochem. 2019;567:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiao J., Pan M., Liu X., Li B., Liu J., Chen Q. A non-enzymatic sensor based on trimetallic nanoalloy with poly (diallyldimethylammonium chloride)-capped reduced graphene oxide for dynamic monitoring hydrogen peroxide production by cancerous cells. Sensors. 2019;20:71. doi: 10.3390/s20010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guler M., Turkoglu V., Bulut A., Zahmakiran M. Electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide using Pd@Ag bimetallic nanoparticles decorated functionalized reduced graphene oxide. Electrochim. Acta. 2018;263:118–126. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.