Abstract

Abstract

Provision of human milk is crucial for maternal and infant health. However, exclusive breastfeeding may exacerbate mood disorders in women unable to achieve this goal. A nuanced approach that considers all aspects of maternal and infant health is needed. In this paper, we bring attention to the potentially negative consequences on maternal and infant health that may be associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the setting of significant challenges. We discuss recent literature exploring the relationship between breastfeeding and maternal mental health, and contextualize it with our first-hand experiences as healthcare professionals who aimed to exclusively breastfeed and encountered difficulties. Given existing evidence and our collective anecdotal experience, we advocate for a balanced approach when supporting parents struggling to breastfeed. Timely recommendations are offered for healthcare providers, medical educators and hospital administrators seeking to balance maternal and infant child health considerations while continuing to promote breastfeeding.

Précis statement

Exclusively promotion of breastfeeding impacts maternal mental health and consequently, infant health. We advocate for balanced considerations of maternal and infant child health while promoting breastfeeding.

Clinical implications

Singular promotion of exclusive breastfeeding may exacerbate adverse maternal mental health outcomes.

A balanced consideration of maternal and infant child health is vital as breastfeeding is encouraged.

Clinicians who provide front-line support to breastfeeding parents must be taught and expected to provide nuanced breastfeeding support that anticipates both physical and mental health challenges.

Subject terms: Quality of life, Scientific community

Introduction

“A woman comes to her postpartum visit with her obstetrician and immediately becomes tearful. She is exhausted, overwhelmed, anxious and depressed. She feels like a failure and feels guilty that despite multiple efforts, she has to supplement her breastmilk with formula as she is not producing sufficient milk for her baby. She has tried multiple over the counter remedies; she pumps after each feeding episode in an attempt to increase her milk supply. She is getting limited sleep because it takes her baby 30 min to feed, then she spends another 15 min getting the baby to sleep, followed by an additional 20 min pumping. She is able to sleep one to two hours before it is time to wake up again and restart the cycle. She has had frequent appointments with the pediatrician because the baby wasn’t gaining adequate weight. She tries very hard to not give formula unless absolutely needed, even though her pediatrician has encouraged her to add formula. She has seen several lactation consultants and occupational therapists specializing in infant feeding. She has started arguing with her husband who feels she should simply stop breastfeeding. He believes she is depressed, anxious, and simply not herself. She says she always planned to breastfeed until her baby was one year of age. She also reminds you of all the information you provided stating that “breast is best” for babies.

Another woman welcomes her first baby filled with anticipation for a long breastfeeding journey. She is a pediatrician and has counseled many mothers about the benefits of breastfeeding. Her friends and family have bought her many breastfeeding “supplies,” such as nursing pads, nipple balms and snacks and teas designed to increase milk supply. She has access to multiple breast pumps. She is excited to begin. Over the course of the first week, she experiences significant pain and difficulty latching her baby. Her baby becomes progressively more and more jaundiced and comes close to needing to be re-hospitalized for treatment for the jaundice. This causes her significant stress and anxiety. She sees the baby’s pediatrician many times and begins to see a lactation consultant regularly. Although her milk eventually comes in and her baby’s weight and bilirubin levels stabilize, the pain and challenges of latching continue for months, as does her anxiety about the baby’s weight. She has countless visits with the pediatrician, lactation consultant and even an infant occupational therapist. She is surrounded by a strong support system and yet she has never felt more alone in her life. She wonders if there is something wrong with her, given that she has all the tools to succeed at breastfeeding but feels like a failure daily. She has cried more in the first months of her baby’s life than she can ever remember crying in her life. Her baby is over three months old before she is able to directly feed him without pain and tears.”

The benefits of breastfeeding for birth parents and their infants are well-documented [1]. Among lactating individuals, breastfeeding is associated with reduced risk of postpartum hemorrhage [1], maternal breast [2], ovarian [3], endometrial and thyroid cancers [1], as well as decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus [4]. For infants, breastfeeding is associated with decreased risk of early ear, gastrointestinal and respiratory infections as well as lower risk of autoimmune conditions later in childhood like inflammatory bowel disease, asthma and diabetes mellitus [1]. Finally, there is well-documented positive impacts on infant neurodevelopment and mother-infant bonding [5, 6]. Perhaps most notably, breastfeeding is also associated with reduced infant mortality [7].

However, the negative experiences and outcomes of birth parents who do not meet their breastfeeding goals also warrant attention and are much less studied. For instance, birth parents who face breastfeeding challenges may be at an increased risk of developing postpartum depression [8]. Although current recommendations for counseling breastfeeding parents now reference awareness of these risks and acknowledgement of potential challenges [9]. Many breastfeeding birth parents continue to be affected by mental health issues related to pain, shame, guilt and feelings of inadequacy. As health and health research professionals with personal and professional expertize in maternal and infant child health, we advocate for a stronger emphasis in clinical practice and medical education on a nuanced approach to messaging around infant feeding that prioritizes maternal mental health as the conduit for optimal infant health. We believe both clinical practice guidelines and medical education modules would benefit from increased language highlighting the potential harm that can be associated with solely promoting exclusive breast milk provision as the foremost goal for all birth parents.

Breastfeeding promotion policies

Because of the myriad health benefits, breastfeeding is rightfully heavily promoted by medical professionals in hospitals, birthing centers, and obstetric and pediatric clinics. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), for example, recommends exclusive breastfeeding for six months and continued breastfeeding as solid foods are introduced for the first year [10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends continued breastfeeding through the first two years of life [11]. In addition, a myriad of local and global strategies have been developed and implemented in the last three decades to promote breastfeeding across the world. For instance, in 1991, the WHO and UNICEF jointly launched the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) as part of a global strategy focused on infant and child nutrition [12]. Hospitals that have implemented these policies have indeed seen increased rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration [12–15]. In addition, the BFHI has been recognized as successful in facilitating the integration of health system-based care and community-level services [12].

Under-explored impacts of exclusive breast milk messaging

Undoubtedly, existing scientific evidence supports both exclusive breastfeeding as a public health goal and the positive impact of public health and hospital-centered initiatives on improved rates of breastfeeding [14]. However, the scarcity of research exploring the impact of exclusive breast milk messaging on women’s well-being is concerning. The act of breastfeeding or pumping for breast milk is physically taxing and can be associated with a variety of adverse outcomes such as mastitis, pain while feeding, soreness after feeding, painful uterine contractions, and dry and bleeding nipples [16]. These complications are common and may be even more likely among lactating individuals with anatomical challenges such as flat or inverted nipples or among those who experience latching difficulties or low milk supply [16]. These physical challenges are exacerbated when a birth parent has little or no social support or has limited infrastructure to support breastfeeding goals such as limited resources for pumping when returning to work or decreased access to trusted lactation consultants.

The physical rigor that breastfeeding/breast milk provision demands of postpartum parents can also be associated with adverse maternal mental health outcomes, especially in the face of challenges. For instance, in a study of nearly 600 women, researchers found that mothers who perceived that they were making poor progress on breastfeeding were more likely to have symptoms of depression than women who perceived their progress to be satisfactory [17]. Other studies have found similar patterns: women who worry about breastfeeding or feel that they have failed to breastfeed were more likely to experience postpartum depression [18, 19]. Although the directionality of the relationship between breastfeeding challenges and postpartum depression is unclear from these studies, the association is concerning. Additionally, many women are uninformed about the intensity of pain experienced with breastfeeding, pain that can be so severe as to generate feeding-related anxiety that negatively impacts the mother-infant bonding relationship [16]. Moreover, women are often surprised by a suboptimal breastfeeding experience since they are uninformed about the physicality of breastfeeding and the emotions of vulnerability that emerge as a result [16]. We can attest, through personal and professional experience, that these issues can compound to leave birth parents with feelings of inadequacy, incompetency and isolation to the great detriment of their mental and overall health. However, research exploring strategies to decrease the risk of such adverse processes from emerging or mitigate their impact on concrete maternal mental health outcomes is lacking.

Equally important and similarly lacking is a better understanding of the incidence and drivers of infant complications that may result from the rigid promotion of exclusive breast milk messaging and other breastfeeding promotion strategies. For instance, there have been several case reports of newborn infants suffering life-threatening complications related to jaundice, hypoglycemia, failure to thrive, and severe dehydration due to insufficient consumption of breastmilk [20, 21]. In addition, there has been growing alarm about reports of sudden unexpected postnatal collapse and their potential association to strict adherence to breastfeeding policies [22]. These associations have crucial public health implications and thus merit rigorous exploration that should occur alongside continued public health and research efforts to promote breastfeeding.

Implications for practice

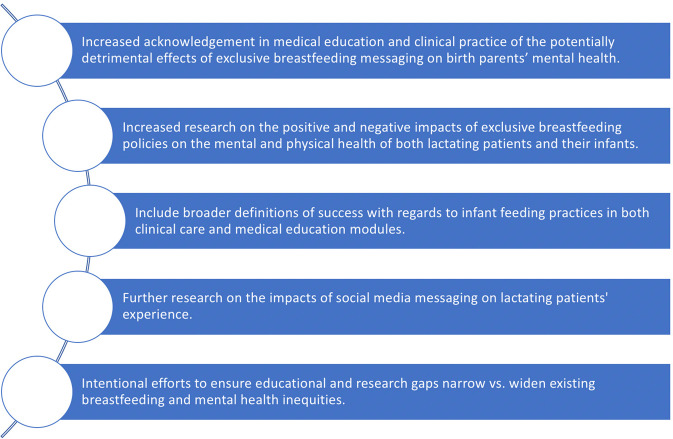

We propose five recommendations for moving forward in a way that balances and advocates for both infant and maternal health in a holistic way (Fig. 1). These recommendations for public health messaging, medical education and research will not only improve our understanding of birth parents who pursue breastfeeding but may also allow us to support early feeding journeys in equitable, partnered ways. First, there must be increased concrete emphasis in both clinical practice and medical education modules of the potential association between the strong recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding/breast milk provision and the negative messaging that some birth parents internalize. Drawing from our personal and professional experiences, these may include thoughts or feelings that the birth parent is “inadequate,” “not good enough”, “a failure” or that they “don’t love their baby enough,” if they are unable to, or choose not to exclusively breastfeed their infant. These feelings or thoughts must be explored and normalized both via public health research and clinical care. Exploring strategies to decrease existing social stigma associated with formula supplementation or cessation of breast milk provision [23] is a critical public health need and a first step in beginning to address the feelings of despair, anxiety, and depression that affected birth parents feel.

Fig. 1. Legend.

Recommendations for a dyad-centered approach to breastfeeding promotion in medicine.

Second, more research is needed on the full impact of promoting exclusive breastfeeding, with a deeper exploration of potential negative impacts on lactating individuals and their infants. Of great concern is the current gap in the literature assessing how birth parents, when pressured to breastfeed by personal beliefs, family, society and health care providers, experience adverse mental health outcomes. A patient-centered community-based approach to this research would be ideal. That is, an approach where mothers and lactating individuals—at all stages and experiences of breastfeeding—are part of the research team from the beginning to provide input on conceptualization of the research questions, designs of the studies, recruitment of participants, and interpretation of findings [24]. Relatedly, studies on how best to support maternal mental health during breastfeeding struggles are also lacking and if done in a patient-centered way, may in turn contribute to improvements in breastfeeding exclusivity and maintenance [25].

Third, it is important to recognize that existing medical education curriculums for clinicians who provide front-line support to breastfeeding parents (i.e., primarily those who practice in obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics and family medicine) do not systematically teach and evaluate trainees’ knowledge about how to address breastfeeding complications like engorgement, latching difficulties, and pain. This educational gap must be addressed in order to improve how well clinicians working closely with breastfeeding parents identify and appropriately address breastfeeding challenges and any potential adverse mental health outcomes in a timely and evidence-based way. In addition, we believe that trainees must be taught to utilize a broader definition of “success” in breastfeeding/breast milk provision when counseling birth parents. Although exclusive breastfeeding may be optimal for many maternal-infant dyads, the associated pressure and experienced challenges in the process may prove detrimental to the combined health outcomes of other dyads. It is thus important for health care providers to learn about and be open to the diverse experience of birth parents and re-define success in breastfeeding in novel ways. To do so, healthcare systems, academic institutions who train healthcare providers and providers themselves may need to more concretely engage in “dyad-centered care” approaches to policies and practices that prioritize both physical and mental health for both birth parents and infants [26].

Fourth, we recommend deeper exploration of the positive and negative impacts of exposure to and participation in social media on women’s breastfeeding and breast milk provision experiences. Digital platforms are increasingly being recognized by researchers as powerful tools for both data collection and public health messaging [27]. While there is some early evidence of supportive benefits to the breastfeeding experience associated with participation in online social media-based groups [28, 29], the potential impact of participation in such groups on maternal mental health is underexplored. In addition, more work is needed to explore the impact of digital media in general on internalized and societally normalized stigma associated with infant feeding decisions.

Finally, we believe all the above issues must be addressed or studied through an equity lens. In the United States, it is well-documented that structural inequities contribute to socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in both breastfeeding and maternal mental health outcomes [30, 31]. Birth parents from low income and historically racially minoritized communities thus sit at the nexus of intersectional risk factors for both breastfeeding and mental health challenges. As educational and research gaps are addressed, it will therefore be critical for educators, scientists and advocates to ensure that any improvements or progress that may emerge from these efforts be equitably distributed. This will require thoughtful planning to recruit diverse research participants for studies that explore novel ways to promote breastfeeding in dyad-centered ways, as well as iterative evaluation of any new quality improvement initiatives, public health programs or healthcare policies to ensure that these narrow rather than widen existing disparities [32].

Conclusion

The provision of breast milk is crucial. It benefits both birth parents and their infants in myriad long-lasting ways. However, optimizing maternal mental health throughout the process of breastfeeding or providing breast milk is equally important to children’s health. This is especially true given that postpartum depression was on the rise before the emergence of the COVID-19 global pandemic [33]. While the full impact of the pandemic on rates of maternal mental health remains to be seen, there is early cross-sectional evidence of worsening rates of peripartum mood disorders associated with COVID-19 [34]. Thus, it is particularly urgent for healthcare systems, medical educators, and healthcare providers to find ways to align the full physical and mental health needs of birth parents with the maternal and infant child health benefits of breast milk provision. We believe the concept of putting the oxygen mask on oneself in the event of an emergency applies directly to the crisis that many breastfeeding birth parents find themselves in during the first few weeks of their infants’ lives. Birth parents should be encouraged to and actively supported in “placing the oxygen mask” on themselves first as they navigate the extremely challenging early weeks of caring for and feeding their babies. To do this will require all involved stakeholders—from health care systems to educators to individual health care providers both within and outside of health care centers—to recognize the nuances at play in the individuals’ lives and support breastfeeding goals while simultaneously prioritizing maternal mental health. Only then might the provision of breast milk realize its true potential on optimal health outcomes for both birthing parents and babies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Alexis R. Jennings, Research Administrator at the University of Florida’s College of Medicine in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, for the support she provided in the revision and submission of this manuscript.

Author contributions

All coauthors have contributed substantially to this manuscript and have seen and approved the version being submitted.

Funding

Diana Montoya-Williams is supported by a NICHD K23 HD102526. The authors otherwise received no financial support for the research and authorship of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Louis-Jacques AF, Stuebe AM. Enabling breastfeeding to support lifelong health for mother and child. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2020;47:363–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Chen J, Li Q, Huang W, Lan H, Jiang H. Association between breastfeeding and breast cancer risk: evidence from a meta-analysis. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:175–82. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danforth KN, Tworoger SS, Hecht JL, Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Breastfeeding and risk of ovarian cancer in two prospective cohorts. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:517–23. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-0130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, Bauman A, Joshy G, Ding D. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in Parous Women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar S, Milanaik R, Adesman A. Long-term neurodevelopmental benefits of breastfeeding. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:559–66. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guxens M, Mendez MA, Moltó-Puigmartí C, Julvez J, García-Esteban R, Forns J, et al. Breastfeeding, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in colostrum, and infant mental development. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e880–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Martines J, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:3–13. doi: 10.1111/apa.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2007;153:1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kellams A. Breastfeeding: Parental education and support. In: Abrams SA, Hoppin AG, eds. UpToDate. UpToDate; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/common-problems-of-breastfeeding-and-weaning 2021.

- 10.Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Guideline: Counselling of Women to Improve Breastfeeding Practices. World Health Organization; 2019. [PubMed]

- 12.Pérez-Escamilla R, Martinez JL, Segura-Pérez S. Impact of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:402–17. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breckenridge JP, Gray N, Toma M, Ashmore S, Glassborow R, Stark C, et al. Motivating Change: a grounded theory of how to achieve large-scale, sustained change, co-created with improvement organisations across the UK. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000553. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spaeth A, Zemp E, Merten S, Dratva J. Baby-Friendly Hospital designation has a sustained impact on continued breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14. 10.1111/mcn.12497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Munn AC, Newman SD, Mueller M, Phillips SM, Taylor SN. The impact in the United States of the baby-friendly hospital initiative on early infant health and breastfeeding outcomes. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:222–30. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2015.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelleher CM. The physical challenges of early breastfeeding. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2727–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis C-L, McQueen K. Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:590–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fergerson SS, Jamieson DJ, Lindsay M. Diagnosing postpartum depression: can we do better? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:899–902. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudron LH, Klein MH, Remington P, Palta M, Allen C, Essex MJ. Predictors, prodromes and incidence of postpartum depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22:103–12. doi: 10.3109/01674820109049960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seske LM, Merhar SL, Haberman BE. Late-onset hypoglycemia in term newborns with poor breastfeeding. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5:501–4. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112:607–19. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass JL, Gartley T, Kleinman R. Unintended consequences of current breastfeeding initiatives. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:923–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bresnahan M, Zhuang J, Goldbort J, Bogdan-Lovis E, Park S-Y, Hitt R. Made to feel like less of a woman: the experience of stigma for mothers who do not breastfeed. Breastfeed Med. 2020;15:35–40. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2019.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minkler M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:S81–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gómez L, Verd S, de-la-Banda G, Cardo E, Servera M, Filgueira A, et al. Perinatal psychological interventions to promote breastfeeding: a narrative review. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16:8. doi: 10.1186/s13006-020-00348-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handley S, Nembhard I. Measuring patient-centered care for specific populations: a necessity for improvement. Patient Experience J. 2020;7:10–2. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merchant RM, South EC, Lurie N. Public health messaging in an Era of social media. JAMA. 2021;325:223–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skelton K, Evans R, LaChenaye J. Hidden Communities of practice in social media groups: mixed methods study. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020;3:e14355. doi: 10.2196/14355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black R, McLaughlin M, Giles M. Women’s experience of social media breastfeeding support and its impact on extended breastfeeding success: a social cognitive perspective. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25:754–71. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Standish, KR, & Parker, MG (2021). Social Determinants of Breastfeeding in the United States. Clinical Therapeutics, S0149-2918(21)00464-1. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Mukherjee S, Trepka MJ, Pierre-Victor D, Bahelah R, Avent T. Racial/Ethnic disparities in antenatal depression in the United States: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1780–97. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1989-x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichman V, Brachio SS, Madu CR, Montoya-Williams D, Peña MM. Using rising tides to lift all boats: Equity-focused quality improvement as a tool to reduce neonatal health disparities. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;26:101198. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2021.101198.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trends in Pregnancy and Childbirth Complications in the U.S. Blue Cross Blue Shield of America; 2020. Accessed March 3, 2021. https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/trends-in-pregnancy-and-childbirth-complications-in-the-us

- 34.Liu CH, Erdei C, Mittal L. Risk factors for depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in perinatal women during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113552. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]