Abstract

Purpose

In-person visits with a trained therapist have been standard care for patients initiating continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). These visits provide an opportunity for hands-on training and an in-person assessment of mask fit. However, to improve access, many health systems are shifting to remote CPAP initiation with equipment mailed to patients. While there are potential benefits of a mailed approach, relative patient outcomes are unclear. Specifically, many have concerns that a lack of in-person training may contribute to reduced CPAP adherence. To inform this knowledge gap, we aimed to compare treatment usage after in-person or mailed CPAP initiation.

Methods

Our medical center shifted from in-person to mailed CPAP dispensation in March 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. We assembled a cohort of patients with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) who initiated CPAP in the months before (n = 433) and after (n = 186) this shift. We compared 90-day adherence between groups.

Results

Mean nightly PAP usage was modest in both groups (in-person 145.2, mailed 140.6 min/night). We did not detect between-group differences in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses (adjusted difference − 0.2 min/night, 95% − 27.0 to + 26.5).

Conclusions

Mail-based systems of CPAP initiation may be able to improve access without reducing CPAP usage. Future work should consider the impact of mailed CPAP on patient-reported outcomes and the impact of different remote setup strategies.

Keywords: Continuous positive airway pressure, Obstructive sleep apnea, Remote care, Adherence, Sleep medicine, Care pathways, Remote care

Introduction

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the traditional first-line treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Despite its efficacy, CPAP is somewhat complex, leading to difficulties as patients start therapy. To reduce difficulties, patients initiating CPAP have traditionally received in-person instruction from a respiratory therapist or technician. During this appointment, a therapist or technician will (1) conduct a hands-on training around the use of CPAP equipment and (2) identify the most appropriate CPAP mask for an individuals’ craniofacial features [1]. While these in-person visits provide opportunities for education and assessment, they can limit access. In-person visits present geographic and logistical barriers for patients and create space and staffing limitations for health systems [2].

The field of sleep medicine is increasingly embracing remote and asynchronous approaches to improve access [3–5]. As part of this shift, some centers have foregone in-person appointments for CPAP initiation, and rely instead on mail-based CPAP dispensation. The mailed approach gained further appeal during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce viral transmission risk. Despite a strong rationale, the relative effectiveness of the mailed approach is unclear. Our primary aim in this analysis is to assess the impact of mailed versus in-person CPAP initiation on treatment usage. To do so, we compare CPAP usage before and after our center’s shift to mailed CPAP initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

The current investigation compares two approaches to CPAP initiation: in-person and mailed.

In-person appointments (standard of care prior to March 2020)

During in-person visits, respiratory therapists instructed patients on CPAP use and provided patients with multiple mask options and a tailored mask fitting. Therapists then activated the patient’s CPAP unit to assess the patient’s tolerance of the prescribed CPAP settings with their chosen mask. Patients were sent home with written instructions around CPAP device usage and contact information for our sleep center.

Mailed appointments (standard of care after March 2020)

In the mailed approach, respiratory therapists placed a telephone call to patients who were prescribed CPAP. During these calls, therapists discussed the basics of CPAP use and confirmed the patient’s mailing address. Therapists then mailed patients a package with a CPAP device, written instructions on device usage and care, a nasal pillow interface with sizing guides, and contact information for our sleep center. In lieu of an in-person mask fitting, respiratory therapists placed a telephone call to patients within 2 weeks of CPAP mailing to ask patients about mask fit, offer alternative masks if necessary, and address any issues or questions around pressure tolerance.

Patient inclusion

Using Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) administrative data and wireless CPAP usage data (ResMed, San Diego, CA), we assembled a cohort of patients with a recent diagnosis of OSA defined as an apnea hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5 using AASM 1A criteria [6]. We identified those initiating CPAP for the first time in the 6 months before our transition (September 2019 through February 2020; In-Person Group) and then 5 months afterward (April through August 2020; Mailed Group). We excluded patients initiating CPAP during the transition month of March.

Confounders of interest

Using VA administrative data, we collected information about potential confounders thought to (1) impact a patients’ likelihood of accessing sleep services during the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) impact usage of CPAP. These confounders included age; self-identified gender and race; drive time from medical center; severity classification by diagnostic AHI; type of sleep testing (home sleep apnea test vs. polysomnogram); Charlson comorbidity index, obesity classification, and prior diagnoses of insomnia, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder [7–9].

Outcomes

We derived our outcomes from data recorded and wirelessly transmitted by patients’ CPAP devices. Our primary outcome is mean nightly CPAP usage over the first 90 days of treatment. Among patients with at least 1 h of cumulative usage, we collected the secondary outcomes of 95th percentile leak, device-detected residual AHI (rAHI), and overall of rAHI ≥ 5 [10].

Statistical analyses

We present baseline characteristics of our in-person and mailed groups within each a priori confounder of interest in Table 1, and present standardized mean differences between groups. Standardized mean differences quantify differences in units of the groups’ pooled standard deviation [11, 12], and are typically interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8) [12].

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| In-person (n = 433) | Mailed (n = 186) | Standardized mean difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |||

| Age (years) | 50.6 (15.2) | 47.0 (13.8) | 0.24 |

| Male sex (%) | 399 (92) | 168 (90) | 0.06 |

| Race | |||

| White | 277 (64) | 132 (71) | 0.20 |

| Black | 73 (17) | 24 (13) | |

| Native American | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Pacific Islander | 11 (3) | 5 (3) | |

| Asian | 27 (6) | 7 (4) | |

| Unknown | 35 (8) | 15 (8) | |

| Multiracial | 8 (2) | 3 (2) | |

| Drive time to medical center | |||

| < 30 min | 74 (17) | 30 (16) | 0.20 |

| 30–59.9 min | 196 (45) | 84 (45) | |

| 60–89.9 min | 111 (26) | 50 (27) | |

| 90–119.9 min | 26 (6) | 17 (9) | |

| ≥ 120 min | 26 (6) | 5 (3) | |

| Charlson score | 1.6 (2) | 1.2 (2) | 0.22 |

| Obesity category | |||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 22 (5) | 9 (5) | 0.21 |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 123 (28) | 48 (26) | |

| 30–34.9 kg/m2 | 148 (34) | 57 (31) | |

| 35–39.9 kg/m2 | 70 (16) | 40 (22) | |

| ≥ 40 kg/m2 | 41 (10) | 13 (7) | |

| Unknown | 29 (7) | 19 (10) | |

| OSA severity | |||

| Mild (AHI 5–14.9) | 154 (36) | 74 (40) | 0.13 |

| Moderate (AHI 15–29.9) | 149 (34) | 67 (36) | |

| Severe (AHI 30 +) | 130 (30) | 45 (24) | |

| Home testing | 296 (68) | 147 (79) | 0.24 |

| Insomnia | 51 (12) | 19 (10) | 0.05 |

| PTSD | 98 (23) | 39 (21) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 103 (24) | 47 (25) | 0.03 |

Legend: SD standard deviation, N number in category, OSA obstructive sleep apnea, AHI apnea hypopnea index, PTSD posttraumatic stress disorder

We compared outcomes of usage, leak, and rAHI between in-person vs. mailed CPAP groups using generalized linear models and used logistic regression to compare incidence of rAHI ≥ 5. For each outcome, we present unadjusted comparisons as well as those adjusted for confounders listed above. Models incorporated all covariates as specified in Table 1, except for logistic regression models which simplified race as White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other to allow a sufficient number of observations per category. We present all differences in outcomes with in-person as the referent group. Our study was approved by the VA Puget Sound Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 619 patients diagnosed with OSA who started CPAP for the first time during our time periods of interest (in-person: n = 433; mailed: n = 186). We present characteristics for each hypothesized confounder in Table 1. Standardized mean differences were < 0.25 for each variable, representing small differences between groups [12]. Although differences were small, we estimated non-negligible differences (standardized mean difference > 0.10) within key variables. The mailed group tended to have slightly younger age (in-person: 50.6, years, mailed: 47.0), less racial diversity (in-person: 36% non-white, mailed: 29%), longer drive time to the medical center (in-person: 38% ≥ 60 min, mailed: 39%), greater prevalence of body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2 (in-person: 26%, mailed: 29%), and lower medical complexity by Charlson score (in-person: 1.6, points, mailed: 1.2). Patients in the mailed group were also more likely to have received a home sleep apnea test (in-person: 68%, mailed: 79%) and tended to have a lower severity of OSA by AHI (in-person: 30% severe OSA, mailed: 24%, Table 1).

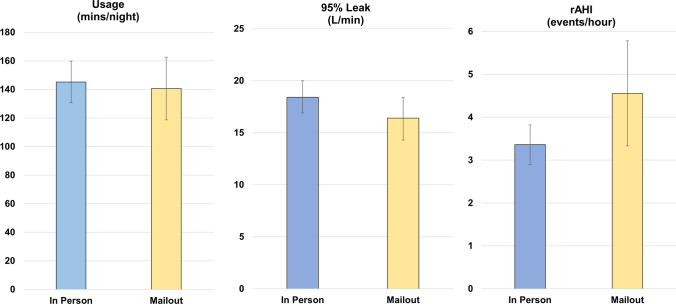

After 90 days, mean nightly PAP usage was modest in both groups (in-person: 145.2 min/night, mailed: 140.6, Fig. 1). We did not detect between-group differences in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

CPAP usage, leak, and residual apnea hypopnea index between groups. Legend: CPAP—continuous positive airway pressure; Min—minutes; L—liter; rAHI, residual apnea hypopnea index. All measures detected by CPAP device. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals of sample mean

Table 2.

Differences in usage, leak, and residual AHI for those with mailed relative to in-person CPAP initiation

| Unadjusted difference | Adjusted difference* | |

|---|---|---|

| Nightly CPAP usage (min/night) | − 4.6 (95% CI − 31.1, + 21.9) | − 0.2 (95% CI − 27.0, + 26.5) |

| 95th percentile leak (L/min) | − 2.1 (95% CI − 4.8, + 0.6) | − 0.8 (95% CI − 3.5, + 1.8) |

| Residual AHI (events/hr) | + 1.2 (95% CI + 0.1, + 2.3) | + 1.3 (95% CI + 0.2, + 2.4) |

Legend: AHI, apnea hypopnea index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CI, confidence interval. *Generalized linear model adjusted for all covariates listed in Table 1. Significant differences in bold

We compared secondary outcomes of leak, rAHI, and prevalence of rAHI ≥ 5 among the 595 patients with at least one hour of cumulative usage (in-person: n = 414, 96%; mailed: n = 181, 97%). Mean 95th percentile leak was 18.4 L/min for in-person and 16.4 L/min for the mailed group, and we did not detect a difference between groups (Table 2). Device-detected rAHI was relatively low in both groups (in-person: 3.4 events/hr, mailed: 4.6, Fig. 1), but was slightly higher in the mailed group (Table 2). Despite differences in rAHI, we did not find that patients with mailed CPAP had greater odds of having rAHI ≥ 5 (in-person: n = 74, 18%; mailed: n = 36, 20%; unadjusted odds ratio: 1.1, 95% CI 0.7–1.8; adjusted odds ratio: 1.2, 95% CI 0.7–1.9).

Discussion

After a shift from in-person to mailed CPAP initiation, we did not observe a difference in CPAP usage or mask leak. Our findings suggest that device-detected rAHI may be slightly greater with mailed CPAP, but the magnitude of the potential difference is of unclear clinical significance. Overall, our results suggest that health systems may be able to transition to mailed CPAP initiation and achieve comparable usage and treatment effectiveness. Coupled with other recent innovations (e.g., telemedicine-based consultation, home sleep apnea testing, autotitrating CPAP) [3–5], mail-based CPAP initiation may allow some patients to be evaluated and treated for OSA without any need for travel.

Our approach benefits from several strengths including a relatively large and well-characterized cohort of patients starting CPAP before and after a center-wide shift to mailed CPAP initiation. However, there are limitations to our approach. First, like other VA samples [13], we observed relatively low nightly usage of CPAP, potentially leading to floor effects in our comparison. Second, while we were able to account for multiple confounders between access and care during the COVID-19 pandemic and CPAP usage, additional confounders likely remain. For instance, our dataset did not include baseline sleep symptoms [8, 9]. Finally, it is worth highlighting that we tested only one approach to mailed CPAP initiation relative to one approach for in-person initiation. It is possible that our results may have differed had our in-person approach prior to the pandemic included more intensive follow-up. Likewise, our findings cannot speak to the role of alternative approaches to remote CPAP instruction and mask selection (e.g., video-based telehealth instruction, more frequent telephone calls).

Nevertheless, our results call into question the necessity of in-person appointments for CPAP initiation. Mail-based CPAP initiation holds the opportunity to improve access and convenience of care, but critical knowledge gaps remain. Future work should test the impact of the mailed approach on patient-centered outcomes and evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different remote setup strategies. Larger samples should also explore heterogeneity across the population and identify patient characteristics associated with greater success with either the in-person or mailed approach. We anticipate that characteristics such as distance from facility, health literacy, and social support may impact which approach would be optimal for a given patient.

Abbreviations

- AHI

Apnea hypopnea index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

- VA

Department of Veterans Affairs

- Hr

Hour

- L

Liter

- Min

Minute

- N

Number

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea

- PTSD

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- rAHI

Residual apnea hypopnea index

- SD

Standard deviation

Author contribution

LMD is the guarantor of this manuscript and takes responsibility for the content, including the data and analysis. All authors met authorship requirements. Study design and collection of data: LMD, APP, JAM, JP, ECP, KH, RS, EE, BNP. Analysis of data: LMD. Interpretation of data: LMD, ECP, CM, KH, RS, JG, BNP. Preparation of manuscript: all authors.

Funding

Dr. Donovan receives support from VA Health Services Research & Development CDA 18–187 and IIR 20–240.

Data availability

Data will only be made available to the public by submitting a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the VA Puget Sound FOIA Officer. Such requests will be evaluated in terms of protecting potential intellectual property value and rights of VA, its employees, collaborators, research sponsors, and any other proprietary or security concerns, including protection of PII, PHI, terms of Confidentiality Agreements or other such restrictions and protections.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the VA Puget Sound Institutional Review Board with approval of retrospective data collection under a waiver of informed consent. Our study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid out in the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Au reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim for service on an advisory board and personal fees from Annals of the American Thoracic Society for service as a deputy editor. This work received continuous positive airway pressure download data for our patient population from ResMed (San Diego, CA). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Role of the sponsors

None of the funding sources were involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of this project.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. To accomplish this study, we received continuous positive airway pressure download data for our patient population from ResMed (San Diego, CA).

Footnotes

Prior abstract publication

We presented an abstract of this work at the 2021 Associated Professional Sleep Societies Virtual Conference, June 10–13, 2021

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Jr, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–276. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.27497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortney JC, Burgess JF, Jr, Bosworth HB, Booth BM, Kaboli PJ. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(Suppl 2):639–647. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1806-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fields BG, Behari PP, McCloskey S, et al. Remote ambulatory management of veterans with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2016;39(3):501–509. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479–504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil SP, Ayappa IA, Caples SM, et al. Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(2):301–334. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3) (Online)

- 7.Collen JF, Lettieri CJ, Hoffman M. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on CPAP adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(6):667–672. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye L, Pack AI, Maislin G, et al. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure use during the first week of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(4):419–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.May AM, Gharibeh T, Wang L, et al. CPAP adherence predictors in a randomized trial of moderate-to-severe OSA enriched with women and minorities. Chest. 2018;154(3):567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drager LF, Malhotra A, Yan Y, et al. Adherence with positive airway pressure therapy for obstructive sleep apnea in developing vs. developed countries: a big data study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(4):703–709. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences.

- 13.Wohlgemuth WK, Chirinos DA, Domingo S, Wallace DM. Attempters, adherers, and non-adherers: latent profile analysis of CPAP use with correlates. Sleep Med. 2015;16(3):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will only be made available to the public by submitting a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the VA Puget Sound FOIA Officer. Such requests will be evaluated in terms of protecting potential intellectual property value and rights of VA, its employees, collaborators, research sponsors, and any other proprietary or security concerns, including protection of PII, PHI, terms of Confidentiality Agreements or other such restrictions and protections.