Abstract

Purpose of Review

Rabies is an ancient yet still neglected tropical disease (NTD). This review focuses upon highlights of recent research and peer-reviewed communications on the underestimated tropical burden of disease and its management due to the complicated dynamics of virulent viral species, diverse mammalian reservoirs, and tens of millions of exposed humans and animals – and how laboratory-based surveillance at each level informs upon pathogen spread and risks of transmission, for targeted prevention and control.

Recent Findings

While both human and rabies animal cases in enzootic areas over the past 5 years were reported to PAHO/WHO and OIE by member countries, still there is a huge gap between these “official” data and the need for enhanced surveillance efforts to meet global program goals.

Summary

A review of the complex aspects of rabies perpetuation in human, domestic animal, and wildlife communities, coupled with a high fatality rate despite the existence of efficacious biologics (but no therapeutics), warrants the need for a One Health approach toward detection via improved laboratory-based surveillance, with focal management at the viral source. More effective methods to prevent the spread of rabies from enzootic to free zones are needed.

Keywords: Encephalitis, Lyssavirus, Neglected tropical diseases, Prophylaxis, Rabies, Zoonosis

Introduction

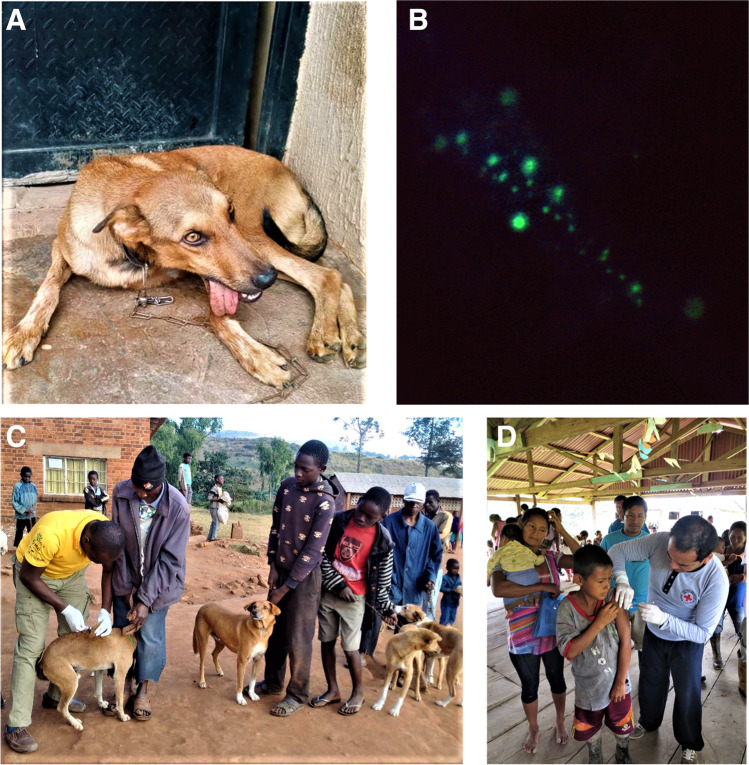

Rabies encompasses multiple biomedical realities and defines the stuff of collective nightmares: an ancient relic of past domestications and subsequent colonizations; a fundamental disease of nature that ensures perpetuation by exploitation of basic mammalian behaviors; a quintessential, highly neurotropic viral etiology; an acute, progressive, incurable encephalitis, caused by several lyssavirus species; a model zoonosis for transdisciplinary, One Health engagement; a case fatality exceeding all other infectious diseases; a personification of panic and pathos; and a vaccine-preventable NTD (i.e., as exemplified by being the first article on this disease for this journal). Given its broad host spectrum among domestic animals and wildlife, rabies is widespread from the Arctic to the southern latitudes, except for Antarctica and Oceania. Currently, the greatest burden falls within lesser developed countries of Africa and Asia, associated primarily with the bites of rabid dogs (Fig. 1, A-D) [1]. Building upon the regional progress obtained throughout the Americas over the past several decades, an extended global program is ongoing towards the elimination of human rabies due to canine rabies by 2030, via the broader use of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to populations at risk, targeted application of postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) to exposed individuals and the mass vaccination of dogs (Fig. 1, C, D). Canine vaccination is a core component of such control and spillover prevention in humans. Because of the large number of free-ranging dogs, annual recruitment of naïve puppies, limited access, affordability of routine veterinary care in many areas, and the need for high (at least 70%) herd immunity, mass canine vaccination campaigns are critical to elimination. While such programs, driven particularly with foreign assistance, offer the potential for major impact, they are not sustainable without local support. Focusing primarily upon recent literature from the past 5 years [1–5, 6•, 7–14, 15•, 16–24, 25•, 26–30, 31•, 32•, 33•, 34–51, 52•, 53, 54•, 55–62, 63••, 64–66, 67•, 68, 69••, 70–83, 84•, 85, 86•, 87•, 88••, 89, 90•, 91–93, 94••, 95–100], the objective of this communication is to provide an update on rabies in the tropics (narrowly defined as those geographic regions between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn) and progress in human and animal case reduction towards the goal of “Zero by Thirty” (ZBT).

Fig. 1.

Illustrative examples of rabies encephalitis, diagnosis, control, and prevention in the tropics. A. Dog showing clinical signs of paralytic rabies (courtesy of Philip P. Mshelbwala). B. Detection of rabies virus antigens in the brain of a rabid dog by the fluorescent antibody test (courtesy of Emmett Booker Shotts, USHUS Public Health Image Library; C. Mass canine vaccination in Malawi (courtesy of Philip P. Mshelbwala) D. Mass human pre-exposure vaccination against rabies in affected Curaray River communities, Loreto Region, Amazon Basin, Peru (courtesy of Sergio E. Recuenco)

Africa

Over 20,000 Africans die from rabies annually, but surveillance data are fragmentary [1]. This projected mortality figure is underestimated, because most cases occur in rural areas with poor healthcare access and limited surveillance [2–4]. As with most NTD, prevention efforts are inadequate, with a lack of funding and political commitment due to a myriad of other priorities, especially during the current pandemic. Hence, program evaluation towards the ZBT is critical.

During 2015, global partners formed a Pan-African Rabies Control Network (PARACON), to unite groups, enhance scientific expertise, and develop strategies for canine rabies elimination through a One Health approach. Unfortunately, most countries have not made significant progress. The Stepwise Approach Towards Rabies Elimination (SARE) provides a logical evaluation of activities, starting from stage zero (i.e., rabies is endemic with no control) to stage five (i.e., freedom from rabies). Recent data show rabies is uncontrolled in most countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of the current stepwise approach towards rabies elimination (SARE) scores* in Africa and Asia (0 for canine rabies-endemic countries and 5 signifying freedom from canine rabies)

| SARE score | No score | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Angola, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Somalia, South Sudan, Togo | Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Niger, Sierra Leone, Somaliland | Kenya, Uganda, Zambia | Benin, Botswana, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania, Zimbabwe | Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Madagascar | Namibia, Zanzibar | |||

| Asia | Myanmar | Lao, Nepal |

China, India, Pakistan |

Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia |

Bhutan, Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam |

*SARE information obtained from the Global Alliance for Rabies Control https://rabiesalliance.org/about/where-we-work

West Africa

Outbreaks of human rabies are notable in West Africa, but PEP is either unavailable or expensive [4]. In Burkina Faso, human rabies deaths occur in the face of low dog vaccination coverage (i.e., 26%) [5]. In Côte d'Ivoire, 637 deaths were identified, 24–47 times official reports [6•]. Between July 2017 and February 2018, seven of eight suspected human cases were confirmed positive in Liberia [7]. Of the 144 apparent healthy dogs tested in Ghana, 2% were rabid [8]. Of 905 animal bite victims in Senegal, 88% were inflicted by suspected rabid dogs, but 5% of patients failed to receive PEP [9]. In Nigeria, canine rabies prevalence was estimated between 3 and 28%, with low dog vaccination rates of 12% to 38% [2]. In Benin, 287 human deaths were reported between 2012 and 2017 [10]. Of 486 suspect animals in Mali, 93% were rabid [11]. There is no current literature for Guinea, Gambia, and Bissau Guinea, but the US CDC classifies these countries as “hotspots” (https://www.cdc.gov/importation/bringing-an-animal-into-the-united-states/high-risk.html). The Regional Disease Surveillance Systems Enhancement (REDISSE) program and other partners support programs throughout West Africa in an attempt to improve upon data collection [28].

East Africa

A century of rabies surveillance supports the view that rabies is endemic in Kenya, and the country has recently implemented a 15-year strategy to end dog-mediated human rabies deaths [29]. Of 37 samples collected from animals in Uganda, 77% were confirmed positive for rabies virus (RABV), even though multiple lyssaviruses are found throughout the continent [12]. In Rwanda, canine rabies evidence is rare. However, a survey in Kigali observed a high level of rabies knowledge (74%) and an understanding of clinical signs (99%), but a low awareness of medical aid after a dog bite (20%) [13]. The US CDC suggests Burundi and Rwanda are hotspots. Canine rabies is abundant in Ethiopia, and a comprehensive country-wide analysis between 2010 and 2020 estimated a random pooled prevalence of rabies of 28% (95% CI: 0–81%) in animals and 33% (95% CI: 20–47%) in humans [14]. Besides being of major public health and agricultural significance, canine rabies also impacts conservation biology due to cross species transmission to highly endangered Ethiopian wolves. Within Tanzania, 19 to 76 exposures per 100,000 persons were estimated in two local districts [15•]. A significant proportion (25%) of people in these communities did not seek medical care due to cost and poor risk assessments. Using Bayesian regression, a recent study estimated 960 human rabies deaths annually in Madagascar [16]. Regarding collaborations within East Africa, the US CDC and other partners support rabies surveillance, prevention, and control activities, through funding and capacity building [15•, 16, 29].

Southern Africa

Once a bastion for control, South Africa has recently confirmed multiple human rabies cases, bringing the national total to at least 17 deaths for 2021. Namibia has progressed in rabies control (SARE score of 2.5), with significant support from the German Government [17]. Before implementing a recent plan, the annual incidence of human rabies was estimated to be 1.0–2.4/100,000 between 2011 and 2017 [18]. Besides rabid dogs, there were multiple confirmed cases among jackals and kudu. In Botswana, one canine rabies outbreak resulted in the death or disappearance of at least 29 highly endangered African wild dogs [19]. In Zambia and Zimbabwe, analysis of multiple isolates from different species found that RABV belonged to one common viral lineage [20]. In Malawi, coordinated domestic animal vaccination was lacking and a single hospital reported several human deaths due to canine rabies. However, since the implementation of mass dog vaccination (Fig. 1, C) by the NGO, Mission Rabies, in May 2015, vaccination coverage has improved (79% in 2015; 78% in 2016; and 72% in 2017) [16]. Elsewhere, in Mozambique, 14 human rabies cases were associated with a low (27%) dog vaccination rate [17].

Central Africa

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a high incidence of rabies (i.e., 5.2 per 1000 person-years) and low community knowledge was recorded [21]. One study in Cameroon observed within-country geographical heterogeneity of dog RABV isolates during 2010 and 2016 [22]. During 2019, a report from the Central African Republic found increased bites by stray dogs and reported two human deaths during 2019 [23]. In Chad, investigators documented low access to PEP (i.e., 8.5%) before implementation of free human vaccination [24]. There were no current data for Angola, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, but the US CDC lists all as hotspots.

Rabies in South and Southeast Asia

Despite widespread underreporting, most global human rabies deaths (~ 60%) occur in Asia, with an associated annual loss of approximately 2.2 million DALYs [1, 25•]. As in Africa, domestic dogs are the main reservoirs and vectors of transmission and areas targeted for vaccination at the source, using a One Health approach [26]. India accounts for most human deaths in Asia (~ 60%). Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Vietnam also have a considerable disease burden [1, 25•]. While Timor Leste, Brunei, the Maldives, and some islands (e.g., the Andaman and Nicobar, and Lakshadweep) in India have been historically “rabies-free”, a few other countries in Asia, such as Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Singapore have eliminated canine rabies by mass dog vaccination and population management programs [27–29]. Several localities are frequent tourist destinations (e.g., Bali) and a major source of guest workers globally, thus contributing to human rabies cases in non-endemic countries world-wide [30].

Nerve tissue vaccines (NTVs) were phased out in all Asian countries by 2015. Only tissue culture or embryonated egg-based rabies vaccines are available for human prophylaxis [25•]. In contrast to Africa, the WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia has promoted the use of dose- and cost-sparing intradermal (ID) vaccination in Member States through policy advocacy and capacity building as one of the strategic approaches to improve accessibility, affordability, and availability of modern human biologics towards the ZBT goal [31•]. To date, ID vaccination, initially introduced and widely used in Thailand, has also been successfully implemented in Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Bangladesh, India, and several other Asian countries. India is the only country in the south and southeast Asian region producing human rabies vaccines and supplying the neighbouring countries. Recently, anti-RABV monoclonal antibody (MAb) products were approved for human PEP in India [32•, 33•]. The use of MAbs may help overcome the limitations relating to supply, cost, and quality of rabies immune globulins in the region.

A meeting organized by the FAO/OIE/WHO tripartite, together with ASEAN representatives during December 2018 in Hanoi, Vietnam, and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in Kathmandu in June 2019, fostered the commitment of the countries in south and southeast Asia towards the ZBT goal [34]. Recent reports highlight the considerable progress towards this goal in some countries, achieved through targeted and diverse initiatives, as well as multiple challenges. Significantly, the Republic of Korea declared the elimination of enzootic transmission of canine rabies in 2017 and have controlled wildlife rabies by oral vaccination [28, 35]. Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Thailand, and Bangladesh have registered a considerable reduction in human rabies deaths [1, 26]. In India, the state of Goa, a global tourist destination, is moving towards canine rabies elimination [34], with no human deaths reported during the last 4 years. In contrast, for the first time in 20 years, Malaysia has reported an outbreak of canine rabies, leading to more than 15 human deaths, highlighting the persistent threat of transboundary incursions [36]. In 2013, rabies was confirmed in ferret-badgers in Taiwan, which has been canine-rabies free since 1961, prompting public health measures to prevent human rabies cases and considerations for wildlife intervention [37]. The SARE scores are available for a few Asian countries (Table 1) [38].

Major challenges in rabies prevention and control efforts throughout Asia include competing health priorities, lack of intersectoral coordination and comprehensive rabies control programs, ineffective surveillance resulting in underestimation of the disease burden, lack of access to PEP, huge stray dog populations, and patchy/ineffective dog vaccination and contraception programs. The shift in global health priorities during the COVID pandemic has impacted measures, as highlighted by the first human death due to rabies since 2016 reported in Bhutan recently, attributed to the challenges in seeking timely PEP and interruption of routine dog vaccination campaigns across porous borders [39]. Optimistically, lessons learned from the pandemic might potentially help strengthen diagnostic capacity, supply chains, regional coordination, and transdisciplinary approaches towards ZBT [39].

The Americas

Considering the historical burden, the Americas has demonstrated the greatest recent progress towards the ZBT goal (and is the only area in which RABV is the sole representative lyssavirus species) by a successful regional strategy [1]. Within North America, Canada and the USA began major mass dog vaccination programs following World War II. Today, these countries report few human cases, either acquired indigenously from wildlife or imported after dog exposure [40]. Increasingly, developing countries within the region are repeating the same positive trend.

Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean

In 1983, Latin American countries, with the coordination by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), began a regional program for canine rabies prevention, control, and elimination. To date, outcomes are well exemplified by Mexico. Since the 1990s, annual mass canine vaccination programs were highly cost-effective, and significantly, during 2019, the country received validation from the WHO as a country free of canine-mediated rabies [41, 42]. No human cases were reported that year, but rabies was detected in 74 rabid animal samples (i.e., primarily livestock mediated by primary wildlife reservoirs) of 22,924 tested [40]. In addition to well-defined reservoirs in bats, wild mesocarnivores (such as coati, foxes, and skunks) are also implicated [43]. Ongoing vigilance is critical, because canine rabies reintroduction is a threat at the southern border, with sporadic reports within Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, where enhanced rabies surveillance, canine vaccination, and human PEP may be less than ideal [44]. Besides canine rabies, hematophagus, insectivorous, and other bats pose a major public health and veterinary threat throughout Central America [45–47]. For example, in Costa Rica, the last autochthonous canine-mediated case of human rabies occurred in the 1970s, in contrast to recent human cases associated with bat RABV [48].

In the Caribbean, only a few localities report rabies (i.e., Cuba, Grenada, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and Tobago), mediated primarily via bat or mongoose RABV, with the exception of canine rabies in Haiti [49]. This nation has the highest poverty rate in the region, as well as the greatest human rabies burden [50]. Over the past decade, there have been multiple initiatives to prevent and control canine rabies in Haiti – including enhanced surveillance, public education, integrated bite case management, expansion of mass parenteral dog vaccination campaigns, and the use of oral vaccination for free-ranging dogs – in attempts towards elimination. Moreover, when traditional methods failed to achieve sufficiently high vaccination levels to interrupt sustained RABV transmission, additional approaches (i.e., using smart-phone technology for spatial coordination and Haitian management team communications) could increase canine vaccination coverage towards 70% [51]. Unfortunately, the combination of environmental disasters, political instability, and setbacks from the COVID19 pandemic has interrupted such progress. Restarting routine dog vaccination programs as soon as possible would prevent thousands of human exposures, saving hundreds of lives annually [52•].

South America

As in other parts of Latin America, South America achieved significant progress in rabies prevention and control by the end of the twentieth century, due to the continental campaign focused on canine vaccination, begun in 1983 [53, 54•]. Several countries reached the elimination of human rabies cases due to dogs, long before the current ZBT goal was launched in 2015. For example, Uruguay reported the last associated human case in 1966, and the last canine rabies epizootic in 1968 [55]. In Chile, the last human case due to canine rabies was in 1990 [56]. Argentina achieved canine rabies control during the 1990s but in 2008 had another human case, with sporadic canine rabies cases until 2020 [57]. Most of the continent is considered canine “rabies-free” except Bolivia, the south of Peru, and parts of Brazil. Human cases due to canine rabies are still reported primarily from Bolivia [54•]. In 2014, Arequipa, in southern Peru, had a reintroduction of canine rabies, just a few months after Peru had declared that area free of dog rabies. Efforts to control the Arequipa outbreak have been unsuccessful. Six years after reintroduction, canine rabies is reestablished as an endemic canine RABV focus, undergoing expansion. Given the efficacy of PEP, no human cases are reported from Arequipa, to date [58–60].

While many South American countries maintain an efficient surveillance system and contribute to the PAHO reporting system (i.e., SIRVERA), the intensity and quality of these activities across various regions are not uniform. Insufficient data are available from some countries (e.g., Venezuela), and weaker surveillance in remote and less populated regions (e.g., indigenous communities in the Amazon Basin) result in delayed or no reporting. Consequently, large areas may appear epidemiologically “silent,” yet present unpredictably with livestock and human rabies outbreaks due to vampire bats [61].

As success in the management of canine rabies progressed in recent decades, simultaneously wildlife rabies emerged in several parts of the continent. Cases were associated with multiple reservoirs unique to the Americas, with human exposures from hematophagous bats in Amazonia and northern Argentina, insectivorous bats in Brazil and Chile, and marmosets in Brazil. Human rabies via a cycle in the common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus, was the most important source of human cases in the twentieth century. Major outbreaks were reported, mainly in Brazil and Peru [62]. Vampire bat RABV variants circulate throughout most of the continent east of the Andes Mountains. From Mexico to Argentina, this area represents the greatest regional burden of rabies among livestock. Such losses of food, milk, and hides impact the local economy for the large livestock producer and perpetuate poverty among farming villages from morbidity and mortality in small ruminants. Peru was most affected by human rabies outbreaks, including clusters of 10 to 20 human deaths, until 2011 when a program of massive PrEP for high-risk areas was launched (Fig. 1, D). So far, this strategy has successfully halted human outbreaks in affected areas, to date [63••, 64, 65]. Considering that bat RABV results in cross species transmission, cats emerged as an intermediate vector of relevance in Colombia and Brazil, due to the frequency of exposures in populations where vampire bats and rabies are present, with exposures and human fatalities via rabid cats [66].

Besides vampire bat rabies, some reports indicate that RABV circulation among insectivorous bats may be more extensive throughout the continent than just in Chile and Brazil. To confirm emergence of these and other reservoirs, improvements in access to timely, local laboratory-based surveillance and genetic characterization are needed across the continent [16]. For example, a nonhuman primate, Callithrix jacchus, the white-tufted marmoset, is now recognized as a RABV reservoir (i.e., the only documented global example among nonhuman primate spp.) in northeastern Brazil, causing human outbreaks over the last 3 decades. This finding is indicative of the potential for other wildlife to emerge as RABV reservoirs within the Neotropics [67•]. In this regard, recent reports also suggest that kinkajous (Potos flavus), a mesocarnivore relative of raccoons, may be an emerging RABV reservoir in Brazil and Peru. With human exposures reported, the public health risk is a concern, requiring further regional molecular and epidemiological confirmation [68].

Despite significant achievements, such progress on rabies prevention and control throughout South America is threatened by the impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in the reduction of canine vaccination activities in the endemic area of Arequipa and reduced access to primary care for exposures due to biomedical staff shortages and supply chain limitations [69••, 70]. Historically, the continent had access to rabies biologics via the revolving fund sponsored by PAHO. Nevertheless, limited information and lack of public health education on the wildlife rabies risks prevent exposed individuals from receiving appropriate and life-saving PEP [71]. Such setbacks within the Americas, a region that served as a model for Africa and Asia towards achieving ZBT, is a major concern for future progress.

Australia

As a continent, Australia is historically free of RABV but is endemic for Australian bat lyssaviruses. During the past decade, preparedness for a possible canine RABV incursion has focused upon northern Australia. This is a vast region and sparsely populated. Many small indigenous communities are located here, and large populations of roaming domestic dogs are a feature. In addition, wild dogs (dingoes and their domestic hybrids) are part of the ecosystem of northern Australia. Given these susceptible populations, the spread of canine RABV throughout southeast Asia, and particularly in Indonesia, has driven recent preparedness research. Components have included demographic studies on roaming domestic dogs and wild dogs, risk assessments, infectious disease spread modelling, and community consultations and policy development.

To prepare for a canine RABV incursion, from surveillance to vaccine needs, the size, distribution, and characteristics of the populations at-risk need to be known. To this effect, the roaming behaviours of dogs in northern Australian indigenous communities have been studied. Research includes using sight-resight techniques to determine the number of roaming dogs within a community [72], measuring the home range and utilization distribution of domestic dogs using GPS collars [73–75], estimating contact rates between dogs [76–78], and identifying risk factors that might promote more extensive canine roaming patterns [8]. The use of miniature video cameras has also been investigated [79]. Canine use for hunting purposes has been described using questionnaire surveys [80]. The wild dog population has been characterized in terms of genetic diversity [81], phenotypes [82], densities and distributions [81], and the potential interactions between wild and domestic dogs [83]. These demographic studies have confirmed that the populations at risk in northern Australia are likely capable of supporting canine RABV infection should an incursion occur and that viral transmission between domestic and wild dogs is likely.

Risk assessments of the likelihood of a canine RABV incursion have been conducted in the Torres Strait [84•], separating the Australian mainland from Papua New Guinea [85]. Part of this process includes identifying possible disease spread pathways, which focus on the “why and how” people might move dogs, such as for trade, gifts, or hunting [86•, 87•]. These risk assessments have concluded that the risk of a canine RABV incursion is non-negligible and depends primarily on the underlying prevalence of rabies in the source population. Thus, ongoing surveillance in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea is critical to inform these risk assessments and for disease preparedness plans.

Finally, models of how rabies might spread through domestic [88••] and wild dog [89, 90•] populations in northern Australia have been developed, based on field research and knowledge of RABV biology. Such models can be used as decision-support systems, for example, to determine how to best use vaccination, should an incursion occur [91, 92]. The output from models creates an opportunity to engage local communities in the process of designing preparedness policy that considers community values [93], such as how domestic dogs are managed versus how a disease outbreak response might be operationalized [94••, 95]. This recent research in northern Australia has contributed significantly towards the cycle of preparedness planning and response [96]. However, additional research activities are needed because of the ever-evolving nature of the rabies threat to northern Australia, and known knowledge gaps, such as how to manage roaming domestic dog populations, how to effectively vaccinate wild dog populations in this environment, and how to conduct disease surveillance in this remote and isolated region. Clearly, progress towards the ZBT goal throughout southeast Asia would greatly lessen the risks for the emergence of canine rabies in Australia. Additionally, the knowledge gained in this traditionally canine RABV-free continent will be instructive to others, once they achieve freedom of human rabies mediated by dogs.

Conclusions

Often ignored or forgotten among NTD, rabies is a vaccine preventable disease. While several antigenically diverse lyssaviruses in Africa and Eurasia are not covered by current biologics, canine RABV poses the most substantial agricultural and public health threats today [97]. Humans and animals continue to die in the twenty-first century because they receive no rabies vaccination [1]. Applied research and new strategies are always welcome in the field. However, all the fundamental tools for essential diagnosis, primary prevention, and epidemiological understanding of this disease were proven during the twentieth century [98]. The ZBT goal remains laudable, and in theory achievable under ideal circumstances, but the repercussions of the current COVID-19 pandemic have impacted all NTD. With the resulting setbacks, there are questions about whether the 2030 timeline remains realistic, especially when viewed in the light of existing (Table 1) SARE scores [99]. In the interim, the perpetuation of the disease, primarily in Africa and Asia, will continue to severely affect tropical human and animal populations and serves as a nidus for those canine rabies-free areas (albeit enzootic for wildlife rabies in some cases) throughout the Americas, Europe, and Australia. As an example, during 2021, even a highly developed, nontropical, canine RABV-free country had an imported human case from rabid dog exposure in Asia, and four other fatalities associated with indigenous RABV from wildlife [100]. Realistic rabies prevention and control are achievable now as a global goal and opportunities abound, despite substantial challenges (Table 2). However, this zoonosis is not a candidate for eradication. Clearly, rabies will continue to pose a major risk for agriculture, public health, and conservation biology in tropical and nontropical regions for the foreseeable future. As the late Ernst Kuwert, Charles Mérieux, Hilary Koprowski, and Konrad Bögel remarked collectively at a major conference in 1985: “…representatives and specialists of different biological disciplines from nearly 70 countries have had the opportunity in Tunis to discuss these important issues and to evaluate, on the basis of their own experimental results and personal epidemiological observations, the possibility of ultimate elimination of rabies in tropical and sub-tropical countries…”. Nearly four decades later, their dream remains to become a reality.

Table 2.

Selected issues for consideration of resolution towards ideal rabies prevention and control goals withing tropical countries

| Challenge | Opportunity |

|---|---|

| No information on local rabies case occurrence | Enhanced, de-centralized, point of care, laboratory-based surveillance, using the most practical OIE and WHO protocols, with related requests for reports by the public and training of community surveillance staff in sample collection |

| Inadequate coordination on animal and human prevention activities | Intersectoral collaboration with Ministries of Agriculture, Environment, Health and others, together with academic institutions and local stakeholders |

| Identification of a program score at or near zero regarding canine rabies management | Development of a national plan in a One Health context, with clearly outlined strategies, defined activities and realistic timelines for monitoring |

| High cost of human rabies biologics | Adoption of dose-sparing, abbreviated schedules for prophylaxis |

| Large numbers of nonexposed individuals seeking prophylaxis | Continuing education for the public using traditional healers and health care providers for application of appropriate risk assessments |

| Unvaccinated populations at occupational or community risk of routine viral exposure | Utilization of new dose-sparing schemes and abbreviated pre-exposure schedules of vaccination |

| Lack of prioritization on zoonoses, such as rabies | Planning for advocacy on World Rabies Day and engagement with national, regional, and global leaders |

| Limited education on rabies | Institution of dog bite prevention guidelines, use first aid after a bite, and basic rabies facts into the school curriculum, adapted to local languages and cultural context |

| Lack of start-up funds to reach the 2030 goal of human rabies elimination mediated by dogs | Partnering with FAO, OIE, WHO and NGOs for initiation assistance with demonstration projects and long-term planning for future country ownership, with procurement of resources for direct collaborations with industry, creation of local production, and identification of emerging markets |

| Unknown number of dogs to vaccinate | Multiple indices and techniques available for the estimation of canine populations, as well as methods for determining the number of vaccinated individuals |

| Difficulty in reaching large numbers of free-ranging (or restricted but hidden owned animals) dogs for parenteral immunization | Focus on responsible dog ownership, improved animal welfare, legislation for mandatory but free domestic animal vaccination, and consideration of appropriate oral vaccination |

| Setbacks from the COVID19 pandemic | Repurposed lessons learned on applied surveillance, diagnostics, biologics, health-care delivery, safety, and virological research |

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to the memory of the late Drs. Ivanete Kotait, Albert B. Ogunkoya, and Shampur N. Madhusudana, who were local champions for rabies prevention and control throughout the Tropics in the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

Declarations

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose relevant to this article and declare no competing interests. In our aim to further strive for objectivity and transparency in research, the authors do disclose unrelated information for reviewers and readers that: CER is a global biomedical consultant to academia, government, industry, and NGOS, a member of the International Steering Committee of the Rabies in the Americas, Inc., and a World Health Organization Expert Technical Advisor on Rabies; PPM serves as an investigator on a grant from the John & Mary Kibble Trust and a consultant for the OIE; SER has provided educational material to the Pan American Health Organization and contributed to the BMJ Epocrates online rabies monography, with annual updates; MPW received an honorarium from the Department of Infectious Diseases and Public Health, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, provided expert testimony for the Australian Federal Court, travel support from the Erasmus + Staff Mobility Program, and has a role in Transboundary and Emerging Diseases (Wiley & Sons).

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on CNS Infections in Tropical Settings

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Charles E. Rupprecht, Email: charleserupprechtii@gmail.com

Reeta S. Mani, Email: drreeta@gmail.com

Philip P. Mshelbwala, Email: p.mshelbwala@uq.net.au

Sergio E. Recuenco, Email: srecuencoc@unmsm.edu.pe

Michael P. Ward, Email: michael.ward@sydney.edu.au

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(4):e0003709-e. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Mshelbwala PP, Weese JS, Sanni-Adeniyi OA, Chakma S, Okeme SS, Mamun AA, et al. Rabies epidemiology, prevention and control in Nigeria: scoping progress towards elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(8):e0009617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbilo C, Coetzer A, Bonfoh B, Angot A, Bebay C, Cassamá B, et al. Dog rabies control in West and Central Africa: a review. Acta Trop. 2021;224:105459. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audu SW, Mshelbwala PP, Jahun BM, Bouaddi K, Weese JS. Two fatal cases of rabies in humans who did not receive rabies postexposure prophylaxis in Nigeria. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(4):749–52. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savadogo M, Tialla D, Ouattara B, Dahourou LD, Ossebi W, Ilboudo SG, et al. Factors associated with owned-dogs' vaccination against rabies: a household survey in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Vet Med Sci. 2021;7(4):1096–106. doi: 10.1002/vms3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.• Kallo V, Keita Z, Boka M, Tetchi M, Dagnogo K, Ouattara M, et al. Rabies burden in Côte d'Ivoire. Acta Tropica. 2021:106249. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.106249. This study estimates rabies burden and financial costs in Côte d'Ivoire, generating data that are crucial for designing an effective rabies prevention and control strategy to attain the ZBT goal.

- 7.Voupawoe G, Varkpeh R, Kamara V, Sieh S, Traoré A, De Battisti C, et al. Rabies control in Liberia: Joint efforts towards zero by 30. Acta Trop. 2021;216:105787. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tasiame W, El-Duah P, Johnson SAM, Owiredu EW, Bleicker T, Veith T, et al. Rabies virus in slaughtered dogs for meat consumption in Ghana: A potential risk for rabies transmission. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021. 10.1111/tbed.14266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Diallo MK, Diallo AO, Dicko A, Richard V, Espié E. Human rabies post exposure prophylaxis at the Pasteur Institute of Dakar, Senegal: trends and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):321. 10.1186/s12879-019-3928-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sessou PND, Houessou E, Tonouhewa A, Ayihou Y, SG Komagbe SG, Farougou F. Temporal evolution of clinical cases of rabies reported in the Atlantique and Littoral Departments from 2012 to 2017 in Southern Bénin. Bull Agron Res Benin. 2019:23-30.

- 11.Traoré A, Keita Z, Léchenne M, Mauti S, Hattendorf J, Zinsstag J. Rabies surveillance-response in Mali in the past 18 years and requirements for the future. Acta Trop. 2020;210:105526. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omodo M, ArGouilh M, Mwiine FN, Okurut ARA, Nantima N, Namatovu A, et al. Rabies in Uganda: rabies knowledge, attitude and practice and molecular characterization of circulating virus strains. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4934-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ntampaka P, Nyaga PN, Niragire F, Gathumbi JK, Tukei M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding rabies and its control among dog owners in Kigali city, Rwanda. PloS one. 2019;14(8):e0210044-e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Belete S, Meseret M, Dejene H, Assefa A. Prevalence of dog-mediated rabies in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2010 to 2020. One Health Outlook. 2021;3(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s42522-021-00046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.• Changalucha J, Steenson R, Grieve E, Cleaveland S, Lembo T, Lushasi K, et al. The need to improve access to rabies post-exposure vaccines: lessons from Tanzania. Vaccine. 2019;37 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):A45-a53. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.086. This study indicates that access to human prophylaxis can be improved and human rabies deaths reduced through a suggested ring-fenced procurement, as well as changing to dose-sparing ID regimens and provision of free vaccination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Rajeev M, Guis H, Edosoa GT, Hanitriniaina C, Randrianarijaona A, Mangahasimbola RT, et al. How geographic access to care shapes disease burden: the current impact of post-exposure prophylaxis and potential for expanded access to prevent human rabies deaths in Madagascar. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(4):e0008821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Athingo R, Tenzin T, Shilongo A, Hikufe E, Shoombe KK, Khaiseb S, et al. Fighting dog-mediated rabies in Namibia-implementation of a rabies elimination program in the northern communal areas. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5(1). 10.3390/tropicalmed5010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Hikufe EH, Freuling CM, Athingo R, Shilongo A, Ndevaetela EE, Helao M, et al. Ecology and epidemiology of rabies in humans, domestic animals and wildlife in Namibia, 2011–2017. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(4):e0007355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canning G, Camphor H, Schroder B. Rabies outbreak in African Wild Dogs (Lycaon pictus) in the Tuli region, Botswana: interventions and management mitigation recommendations. J Nat Conserv. 2019;48:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muleya W, Chambaro HM, Sasaki M, Gwenhure LF, Mwenechanya R, Kajihara M, et al. Genetic diversity of rabies virus in different host species and geographic regions of Zambia and Zimbabwe. Virus Genes. 2019;55(5):713–719. doi: 10.1007/s11262-019-01682-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mbilo C, Kabongo JB, Pyana PP, Nlonda L, Nzita RW, Luntadila B, et al. Dog ecology, bite incidence, and disease awareness: a cross-sectional survey among a rabies-affected community in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Vaccines (Basel). 2019;7(3). 10.3390/vaccines7030098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Sadeuh-Mba SA, Momo JB, Besong L, Loul S, Njouom R. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic relatedness of dog-derived rabies viruses circulating in Cameroon between 2010 and 2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(10):e0006041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalthan E, Banawane FO, Yagata-Moussa EF, Mbaikoua MN, Wea-Yougaye D. Responses to the risk of canine and human rabies in the City of Sibut, Central African Republic. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2020;113(1):39–41. doi: 10.3166/bspe-2020-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madjadinan A, Hattendorf J, Mindekem R, Mbaipago N, Moyengar R, Gerber F, et al. Identification of risk factors for rabies exposure and access to post-exposure prophylaxis in Chad. Acta Trop. 2020;209:105484. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.• World Health Organization. WHO expert consultation on rabies: third report: WHO Technical Series Report #1012; 2018, Geneva, Switzerland. This report provides the most current data on rabies prevention and control worldwide, and supersedes the report of the second WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies, published in 2012.

- 26.Acharya KP, Subedi D, Wilson RT. Rabies control in South Asia requires a One Health approach. One Health. 2021;19(12):100215. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenzin, Ward MP. Review of rabies epidemiology and control in South, South East and East Asia: past, present and prospects for elimination. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;59(7):451–67. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Yang DK, Cho IS, Kim HH. Strategies for controlling dog-mediated human rabies in Asia: using 'One Health' principles to assess control programmes for rabies. Rev Sci Tech. 2018;37(2):473–481. doi: 10.20506/rst.37.2.2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gongal G, Wright AE. Human Rabies in the WHO Southeast Asia Region: forward steps for elimination. Advances in preventive medicine. 2011;2011:383870-. 10.4061/2011/383870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Gautret P, Diaz-Menendez M, Goorhuis A, Wallace RM, Msimang V, Blanton J, et al. Epidemiology of rabies cases among international travellers, 2013–2019: A retrospective analysis of published reports. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36:101766. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.• Gongal G, Sampath G. Introduction of intradermal rabies vaccination - a paradigm shift in improving post-exposure prophylaxis in Asia. Vaccine. 2019;37 Suppl 1:A94-A98. This article highlights various aspects of intradermal rabies vaccination, including the scientific basis, evolution, cost-effectiveness, and the challenges in implementation in Asia. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.• Gogtay NJ, Munshi R, Ashwath Narayana DH, Mahendra BJ, Kshirsagar V, Gunale B, et al. Comparison of a novel human rabies monoclonal antibody to human rabies immunoglobulin for postexposure prophylaxis: a phase 2/3, randomized, single-blind, noninferiority, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):387–95. 10.1093/cid/cix791. This paper describes the safety and efficacy of an anti-rabies monoclonal antibody products for human rabies post-exposure prophylaxis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.• Kansagra K, Parmar D, Mendiratta SK, Patel J, Joshi S, Sharma N, et al. A Phase 3, randomized, open-label, noninferiority trial evaluating anti-rabies monoclonal antibody cocktail (TwinrabTM) against human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG). Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e2722-e8. 10.1093/cid/ciaa779. This paper documents the safety and efficacy of an anti-rabies monoclonal antibody cocktail for human rabies post-exposure prophylaxis, and together with reference 32, for the first time anywhere worldwide, provides clinical evidence on both products, which are currently licensed for use in India and are expected to help overcome the limitations of currently available biologics for passive immunization in Asia. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Rupprecht CE, Abela-Ridder B, Abila R, Amparo AC, Banyard A, Blanton J, et al. Towards rabies elimination in the Asia-Pacific region: from theory to practice. Biologicals. 2020;64:83–95. 10.1016/j.biologicals.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Yang DK, Kim HH, Lee KK, Yoo JY, Seomun H, Cho IS. Mass vaccination has led to the elimination of rabies since 2014 in South Korea. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2017;6(2):111–119. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2017.6.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taib NAA, Labadin J, Piau P. Model simulation for the spread of rabies in Sarawak, Malaysia. Int J Adv Sci Eng Inf Technol. 2019;9:1739–1745. doi: 10.18517/ijaseit.9.5.10230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang AS, Chen WC, Huang WT, Huang ST, Lo YC, Wei SH, et al. Public health responses to reemergence of animal rabies, Taiwan, July 16-December 28, 2013. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Report of workshop on enhancing progress towards rabies elimination “zero by 30” in the SAARC Region, Kathmandu, Nepal; 26–28 June 2019 [Online] Available: https://rr-asia.oie.int/en/events/workshop-on-enhancing-progress-towards-rabies-elimination-zero-by-30-in-the-saarc-region/

- 39.Nadal D, Beeching S, Cleaveland S, Cronin K, Hampson K, Steenson R, et al. Rabies and the pandemic: lessons for One Health. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2021. 10.1093/trstmh/trab123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Ma X, Monroe BP, Wallace RM, Orciari LA, Gigante CM, Kirby JD, et al. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2019. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2021;258(11):1205–20. doi: 10.2460/javma.258.11.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Del Rio Vilas VJ, Freire de Carvalho MJ, Vigilato MA, Rocha F, Vokaty A, Pompei JA, et al. Tribulations of the Last Mile: Sides from a Regional Program. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:4. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2017.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.González-Roldán JF, Undurraga EA, Meltzer MI, Atkins C, Vargas-Pino F, Gutiérrez-Cedillo V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the national dog rabies prevention and control program in Mexico, 1990–2015. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaramillo-Reyna E, Almazán-Marín C, de la OCME, Valdéz-Leal R, Bañuelos-Álvarez AH, Zúñiga-Ramos MA, et al. Public veterinary medicine: public health rabies virus variants identified in Nuevo Leon State, Mexico, from 2008 to 2015. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2020;256(4):438–43. 10.2460/javma.256.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.World Health Organization Human rabies: 2016 updates and call for data. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92(7):77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arias-Orozco P, Bástida-González F, Cruz L, Villatoro J, Espinoza E, Zárate-Segura PB, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of canine rabies in El Salvador: violence and poverty as social factors of canine rabies. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warembourg C, Fournié G, Abakar MF, Alvarez D, Berger-González M, Odoch T, et al. Predictors of free-roaming domestic dogs' contact network centrality and their relevance for rabies control. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12898. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moran D, Juliao P, Alvarez D, Lindblade KA, Ellison JA, Gilbert AT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding rabies and exposure to bats in two rural communities in Guatemala. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:955. doi: 10.1186/s13104-014-0955-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.León B, González SF, Solís LM, Ramírez-Cardoce M, Moreira-Soto A, Cordero-Solórzano JM, et al. Rabies in Costa Rica - next steps towards controlling bat-borne rabies after its elimination in dogs. Yale J Biol Med. 2021;94(2):311–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seetahal JFR, Vokaty A, Vigilato MAN, Carrington CVF, Pradel J, Louison B, et al. Rabies in the Caribbean: a situational analysis and historic review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(3). 10.3390/tropicalmed3030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Wallace R, Etheart M, Ludder F, Augustin P, Fenelon N, Franka R, et al. The health impact of rabies in haiti and recent developments on the path toward elimination, 2010–2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(4_Suppl):76–83. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monroe B, Ludder F, Dilius P, Crowdis K, Lohr F, Cleaton J, et al. Every dog has its data: evaluation of a technology-aided canine rabies vaccination campaign to implement a microplanning approach. Front Public Health. 2021;9:757668. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.757668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.• Kunkel A, Jeon S, Joseph HC, Dilius P, Crowdis K, Meltzer MI, et al. The urgency of resuming disrupted dog rabies vaccination campaigns: a modeling and cost-effectiveness analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12476. 10.1038/s41598-021-92067-5. Indicates the potential impact of disruptions upon current prevention activities and the repercussions if such setbacks occur and are not resolved in a timely manner. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Escobar Cifuentes E. Program for the elimination of urban rabies in Latin America. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10 Suppl 4:S689–92. 10.1093/clinids/10.supplement_4.s689. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.• Freire de Carvalho M, Vigilato MAN, Pompei JA, Rocha F, Vokaty A, Molina-Flores B, et al. Rabies in the Americas: 1998–2014. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(3):e0006271. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006271. Introduction to the successful regional campaign towards canine rabies elimination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Ministerio de Salud Uruguay. Boletín Epidemiológico Agosto 2017. Available from: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/sites/ministerio-salud-publica/files/documentos/publicaciones/Bolet%C3%ADn%20epidemiol%C3%B3gico%20Agosto%202017.pdf.

- 56.Laval RE, Lepe IP. A historical view of rabies in Chile. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2008;25(2):S2–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ministerio de Salud Argetina. Guía para la prevención, vigilancia y control de la rabia en Argentina. 2018. Available from: http://saladesituacion.salta.gov.ar/php/documentos/materiales_descarga_programas_epi/zoonosis/guia_rabia-2018.pdf.

- 58.Castillo-Neyra R, Zegarra E, Monroy Y, Bernedo RF, Cornejo-Rosello I, Paz-Soldan VA, et al. Spatial association of canine rabies outbreak and ecological urban corridors, Arequipa, Peru. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2017;2(3):38. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed2030038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De la Puente-León M, Levy MZ, Toledo AM, Recuenco S, Shinnick J, Castillo-Neyra R. Spatial inequality hides the burden of dog bites and the risk of dog-mediated human rabies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1247–57. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Recuenco Cabrera S. Persistence of the reemergence of canine rabies in south Peru. An Fac med. 2019;80(3):379–82. doi: 10.15381/anales.803.16866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meske M, Fanelli A, Rocha F, Awada L, Soto PC, Mapitse N, et al. Evolution of rabies in south america and inter-species dynamics (2009–2018). Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6(2). 10.3390/tropicalmed6020098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Vigilato MA, Cosivi O, Knöbl T, Clavijo A, Silva HM. Rabies update for Latin America and the Caribbean. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(4):678–679. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.121482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.•• Kessels JA, Recuenco S, Navarro-Vela AM, Deray R, Vigilato M, Ertl H, et al. Pre-exposure rabies prophylaxis: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(3):210–9c. 10.2471/blt.16.173039. Describes the overlooked but important role that vaccination plays in human populations at risk of rabies virus exposure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Recuenco SE. Rabies vaccines, prophylactic, Peru: massive rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis for High-risk populations. Rabies and Rabies Vaccines. 2020:83.

- 65.Benavides JA, Rojas Paniagua E, Hampson K, Valderrama W, Streicker DG. Quantifying the burden of vampire bat rabies in Peruvian livestock. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(12):e0006105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arias Caicedo MR, Arias Caicedo CA, Andrade Monteiro E, Abel I, de Arruda Xavier D. Spatiotemporal analysis of human rabies exposure in Colombia during ten years: A challenge for implementing social inclusion in its surveillance and prevention. 2019. 10.1101/553909.

- 67.• Escobar LE, Peterson AT, Favi M, Yung V, Medina-Vogel G. Bat-borne rabies in Latin America. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57(1):63–72. 10.1590/s0036-46652015000100009. Underscores the threat of enzootic wildlife rabies even after successful canine rabies vaccination campaigns. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Dell'Armelina Rocha PR, Velasco-Villa A, de Lima EM, Salomoni A, Fusaro A, da Conceição Souza E, et al. Unexpected rabies variant identified in kinkajou (Potos flavus), Mato Grosso, Brazil. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):851–4. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1759380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.•• Raynor B, Díaz EW, Shinnick J, Zegarra E, Monroy Y, Mena C, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rabies reemergence in Latin America: the case of Arequipa, Peru. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.08.06.20169581. Describes the major setbacks resulting from the pandemic on a previously successful program.

- 70.Castillo-Neyra R, Buttenheim AM, Brown J, Ferrara JF, Arevalo-Nieto C, Borrini-Mayorí K, et al. Behavioral and structural barriers to accessing human post-exposure prophylaxis and other preventive practices in Arequipa, Peru, during a canine rabies epidemic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0008478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duarte NFH, Pires Neto RDJ, Viana VF, Feijão LX, Alencar CH, Heukelbach J. Clinical aspects of human rabies in the state of Ceará, Brazil: an overview of 63 cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2021;54:e01042021. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0104-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Ward MP. Demographic studies of owned dogs in the Northern Peninsula Area, Australia, to inform population and disease management strategies. Aust Vet J. 2018;96(12):487–94. doi: 10.1111/avj.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Molloy S, Burleigh A, Dürr S, Ward MP. Roaming behaviour of dogs in four remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Australia: preliminary investigations. Aust Vet J. 2017;95(3):55–63. doi: 10.1111/avj.12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Dürr S, Ward MP. Domestic dog roaming patterns in remote northern Australian indigenous communities and implications for disease modelling. Prev Vet Med. 2017;146:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maher EK, Ward MP, Brookes VJ. Investigation of the temporal roaming behaviour of free-roaming domestic dogs in Indigenous communities in northern Australia to inform rabies incursion preparedness. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14893. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51447-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bombara C, Dürr S, Gongora J, Ward MP. Roaming of dogs in remote Indigenous communities in northern Australia and potential interaction between community and wild dogs. Aust Vet J. 2017;95(6):182–8. doi: 10.1111/avj.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brookes VJ, VanderWaal K, Ward MP. The social networks of free-roaming domestic dogs in island communities in the Torres Strait, Australia. Prev Vet Med. 2020;181:104534. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Ward MP, Dürr S. Using roaming behaviours of dogs to estimate contact rates: the predicted effect on rabies spread. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e135. doi: 10.1017/s0950268819000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dürr S, Dhand NK, Bombara C, Molloy S, Ward MP. What influences the home range size of free-roaming domestic dogs? Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(7):1339–50. doi: 10.1017/s095026881700022x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gabriele-Rivet V, Brookes VJ, Arsenault J, Ward MP. Hunting practices in northern Australia and their implication for disease transmission between community dogs and wild dogs. Aust Vet J. 2019;97(8):268–276. doi: 10.1111/avj.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gabriele-Rivet V, Arsenault J, Brookes VJ, Fleming PJS, Nury C, Ward MP. Dingo density estimates and movements in equatorial australia: spatially explicit mark-resight models. Animals (Basel). 2020;10(5). 10.3390/ani10050865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Brookes VJ, Degeling C, van Eeden LM, Ward MP. What Is a Dingo? The phenotypic classification of Dingoes by Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander residents in Northern Australia. Animals (Basel). 2020;10(7). 10.3390/ani10071230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Gabriele-Rivet V, Brookes VJ, Arsenault J, Ward MP. Seasonal and spatial overlap in activity between domestic dogs and dingoes in remote Indigenous communities of northern Australia. Aust Vet J. 2021;99(4):114–8. 10.1111/avj.13047. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.• Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Ward MP. Assessing the risk of a canine rabies incursion in Northern Australia. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:141. 10.3389/fvets.2017.00141. Illustrates a practical example of risk assessment applied to rabies virus spread from endemic to free zones of infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Brookes VJ, Keponge-Yombo A, Thomson D, Ward MP. Risk assessment of the entry of canine-rabies into Papua New Guinea via sea and land routes. Prev Vet Med. 2017;145:49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.• Brookes VJ, Degeling C, Ward MP. Going viral in PNG - Exploring routes and circumstances of entry of a rabies-infected dog into Papua New Guinea. Soc Sci Med. 2018;196:10–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.006. Describes the process for identifying pathways of rabies virus spread from endemic to free zones of infection. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.• Brookes VJ, Ward MP. Expert opinion to identify high-risk entry routes of canine rabies into Papua New Guinea. Zoonoses Public Health. 2017;64(2):156–60. 10.1111/zph.12284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.•• Brookes VJ, Dürr S, Ward MP. Rabies-induced behavioural changes are key to rabies persistence in dog populations: investigation using a network-based model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(9):e0007739. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007739. Provides an evidence-based explanation for the persistence of rabies virus within small populations of domestic dogs, and implications for sureveillance and control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Johnstone-Robertson SP, Fleming PJS, Ward MP, Davis SA. Predicted spatial spread of canine rabies in Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(1):e0005312-e. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.• Gabriele-Rivet V, Ward MP, Arsenault J, London D, Brookes VJ. Could a rabies incursion spread in the northern Australian dingo population? Development of a spatial stochastic simulation model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(2):e0009124. Investigates how the wild−domestic dog interface can potentially influence the spread of rabies virus, by the use of disease spread modelling informed by empirical field data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Dürr S, Ward MP. Modelling targeted rabies vaccination strategies for a domestic dog population with heterogeneous roaming patterns. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(7):e0007582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Dürr S, Ward MP. Targeted pre-emptive rabies vaccination strategies in a susceptible domestic dog population with heterogeneous roaming patterns. Prev Vet Med. 2019;172:104774. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.104774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brookes VJ, Kennedy E, Dhagapan P, Ward MP. Qualitative research to design sustainable community-based surveillance for rabies in Northern Australia and Papua New Guinea. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:19. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2017.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.•• Degeling C, Brookes V, Lea T, Ward M. Rabies response, One Health and more-than-human considerations in Indigenous communities in northern Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;212:60–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.006. Describes how community norms and expectations can influence the design of rabies response policies, without which resposne and control programs are unlikely to succeed. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 95.Brookes VJ, Ward MP, Rock M, Degeling C. One Health promotion and the politics of dog management in remote, northern Australian communities. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12451. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69316-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ward MP, Brookes VJ. Rabies in our neighbourhood: preparedness for an emerging infectious disease. Pathogens. 2021;10(3). 10.3390/pathogens10030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Fooks AR, Shipley R, Markotter W, Tordo N, Freuling CM, Müller T, McElhinney LM, Banyard AC, Rupprecht CE. Renewed Public Health Threat from Emerging Lyssaviruses. Viruses. 2021;13(9):1769. doi: 10.3390/v13091769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rupprecht CE, Salahuddin N. Current status of human rabies prevention: remaining barriers to global biologics accessibility and disease elimination. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(6):629–640. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1627205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Changalucha J, Hampson K, Jaswant G, Lankester F, Yoder J. Human rabies: prospects for elimination. CAB Rev. 2021;16:039. doi: 10.1079/pavsnnr202116039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kunkel A, Minhaj FS, Whitehill F, Austin C, Hahn C, Kieffer AJ, et al. Three human rabies deaths attributed to bat exposures - United States, August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(1):31–32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7101a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]