Abstract

Background:

Adolescent females presenting to emergency departments (EDs) inconsistently use contraceptives. We aimed to assess implementation outcomes and potential efficacy of a user-informed, theory-based digital health intervention developed to improve sexual and reproductive health for adolescent females in the ED.

Methods:

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial of sexually active female ED patients age 14-19 years. Participants were randomized to the intervention Dr. Erica (Emergency Room Interventions to improve the Care of Adolescents) or usual care. Dr. Erica consists of an ED-based digital intervention along with 3 months of personalized and interactive multi-media messaging. We assessed the feasibility, adoption and fidelity of Dr. Erica among adolescent female users. Initiation of highly effective contraception was the primary efficacy outcome.

Results:

We enrolled 146 patients; mean age was 17.7 (SD+/−1.27) years and 87% were Hispanic. Dr. Erica demonstrated feasibility, with high rates of consent (84.4%) and follow up (82.9%). Intervention participants found Dr. Erica acceptable, liking (98.0%; on Likert scale) and recommending (83.7%) the program. 87.5% adopted the program, responding to ≥1 text; a total of 289 weblinks were clicked. Dr. Erica demonstrated fidelity; few participants opted out (6.9%) and failed to receive texts (1.4%). Contraception was initiated by 24.6% (14/57) in the intervention and 21.9% (14/64) in the control arms (absolute risk difference (ARD) =2.7%, 95% CI −12.4%, 17.8%). Participants receiving Dr. Erica were more likely to choose a method to start in the future (65.9% (27/41) than controls ((30.0%;15/50); ARD =35.9%, 95% CI 16.6%, 55.1%).

Conclusion(s):

A personalized, interactive digital intervention was feasible to implement, acceptable to female ED patients, and demonstrated high fidelity and adoption. This ED-based intervention shows potential to improve contraception decision-making.

Keywords: Teenage pregnancy, Emergency medicine, Pregnancy prevention, Sexual health, Family planning counseling, Adolescent behavior, Contraception behavior, Health planning, Pregnancy in adolescence, Sexual behavior, Text messaging, Digital health, Mobile health

INTRODUCTION

Emergency departments (EDs) provide medical care for 19 million adolescents annually in the United States (US); many are poor, minoritized and have limited access to primary care.1,2 Despite growing interest in expanding the role of the ED to provide preventive care, limited resources, time constraints, and system barriers have limited implementation of innovative preventive health interventions in the ED.3 Thus, few effective, ED-based preventive health interventions have been rigorously developed or tested.4

Adolescents ED patients are often sexually active and inconsistently using contraceptives.5 Although female ED patients are receptive to initiating effective contraceptive methods, ED physicians are reluctant to initiate sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care due to the competing demands in the ED such as high volumes and acuity.6,7 Since few patients follow up to outpatient SRH services when referred, behavioral change interventions beginning with an ED visit could be critical opportunities to fill the gap in the SRH health care.4,8 Similar to other successful ED-based programs, an intervention that aims to improve adolescent SRH should be evidence-based and multi-disciplinary with ED providers working as a comprehensive team to create a program that fits the needs of local population.3

One strategy to provide preventive care beginning in the ED is the use of mobile health (mHealth). Digital interventions to promote SRH have been shown to increase sexual health knowledge and positively impact sex norms and attitudes.9 Outpatient mHealth interventions, such as Girl2Girl and Health-E You, increased rates of birth control use among adolescent cisgender LGB+ females and Latina adolescents, respectively.10,11 However, none of the interventions were tested in the ED setting. It is unclear if a mHealth intervention initiated in the ED can improve the SRH of adolescent patients.

Our collaborative multi-disciplinary team has developed a user-informed, theory-based mHealth intervention titled Dr. Erica (Emergency Room Intervention to improve the Care of Adolescents). Dr. Erica targets sexually active female adolescent ED patients who do not want to become pregnant.12 Employing a user-centered design framework, Dr. Erica was designed to convert evidence-based SRH information into an engaging text messaging platform based directly on the input of our adolescent ED population. The aims of the current pilot randomized controlled trial were (1) to assess the feasibility, acceptability, adoption and fidelity of Dr. Erica in the ED setting, and (2) to evaluate the potential efficacy of Dr. Erica. We hypothesized that Dr. Erica would be feasible to implement in the ED with adolescent female patients, be acceptable to adolescent females, and demonstrate high adoption and fidelity among users. Successful implementation and initial evidence of efficacy of Dr. Erica would warrant a subsequent definitive trial to test the hypothesis that sexually active adolescent females who receive Dr. Erica will more often initiate highly effective contraceptives than those who receive standard referral to primary care alone.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective randomized controlled pilot trial in an urban, tertiary-care pediatric ED with 53,000 annual visits. The ED population is predominantly Hispanic, publicly insured, and of low socioeconomic status. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Participants

Included patients were female ED patients aged 14-19 years who self-reported that they were sexually active with males in the past 3 months and were not currently using, and at last intercourse did not use, a highly effective contraceptive. All patients, regardless of chief complaint, were eligible for screening. As defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we selected highly effective contraceptives (Tier 1 and 2) as those with lower contraceptive failure rates, which corresponds to less than 10 out of every 100 women experiencing an unintended pregnancy within the last year of typical use.13,14 These methods include the intrauterine or implantable device, shot (Depo-Provera or medroxyprogesterone acetate), ring (NuvaRing), transdermal patch (Ortho Evra), or oral contraceptive pills. We included those females who only used condoms (Tier 3), as the failure rate for condoms is 18 out of 100 women. We excluded females who did not speak English, did not live locally, did not own a mobile phone, were currently pregnant, were critically ill, were in foster care or wards of the state, had significant cognitive delay, or had reported that they would like to become pregnant. This final exclusion criterion, wanting to become pregnant in the next year, was based on One Key Question®, which was developed to respect a woman’s desire for or ambivalence about pregnancy.15

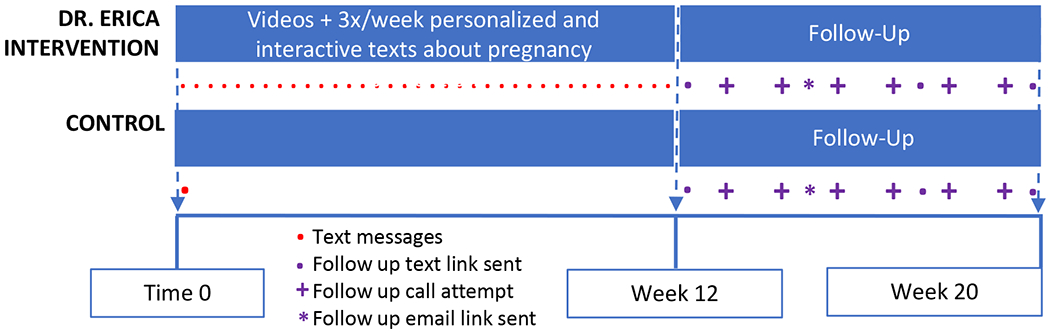

Study Procedures

Research coordinators screened ED patients during consecutive hours, Monday-Friday, 8am to 10pm, with some limited time for enrollment during weekend hours. Participants were enrolled with informed consent and had follow-up completed along the timeline noted in Figure 1. For participants aged 14-17, we obtained 2-person verification of agreement to participate (i.e., research coordinator and ED attending) and the IRB granted a waiver of parental consent. Participants received a $10 gift card at enrollment.

Figure 1.

Timeline of study procedures.

Participants were assigned to intervention versus usual care with 1:1 allocation ratio by using a computer-generated block randomization.16 We concealed allocation by using sequentially numbered envelopes which were opened after consent. Research staff then entered participant data into the mobile health platform. Participants completed a brief, baseline, tablet-based questionnaire focusing on demographics, use of medical care, sexual practices and behaviors, and pregnancy intentions.17,18 All participants also received an introductory text message from the Dr. Erica automated platform on their own phones.

Arms

The development and design of Dr. Erica has been published previously.12 In summary, Dr. Erica was created using intervention mapping, a program-planning framework.19 We incorporated the theoretical perspective of the Social Cognitive Theory and Motivational Interviewing, which is frequently associated with successful contraception promotion interventions and pilot tested the program using patient-centered design methodology.20–23 The program incorporated 8 key components to increase engagement: personalization, interactivity, tailoring, feedback loops, visual stimuli, links and role modeling, and social media.

Dr. Erica consists of two parts—a digital ED-based brief intervention and multi-media text messaging. The ED-based component consisted of a Powtoons® introductory video and a 7-minute patient-centered contraception education video (courtesy of Beyond the Pill).24 The program then sent a series of text messages over the following 10 weeks. Texts sent on most Mondays and Fridays began with an interactive text message chain, leading to a total of 18 interactive texting algorithms. Texts sent on Wednesdays consisted of GIFs and cartoon Instagram® images; these were not interactive. In total, Dr. Erica sent a minimum of 56 and maximum of 121 texts, with additional texts sent based on keywords. The mobile platform provider (RipRoad®) conducted all automated texting dialogue compliant to HIPAA and Code of Federal Regulations and stored all libraries of branched-logic messages and responses. All texts were time-stamped, recorded, and accessible to investigators.

While the majority of Dr. Erica was a fully automated behavioral intervention technology, we hosted “LIVE Office Hours.”25 When a participant texted into the program, this triggered an automated response acknowledging the received text and explaining how a trained confidential sexual health counselor would respond to questions within 72 hours. An expert in adolescent sexual health (LC) sorted through these responses in real time. Those participants who posted a short response, such as “sounds good to me,” did not receive another response. Those participants who texted a question were invited to LIVE Office Hours occurring three evening each week. This expert used that time to answer questions and engage in a real-time dialogue using a guidebook of frequently asked questions courtesy of an established sexual health text messaging program.26

Those randomized to usual care received an introductory text message to ensure texting capabilities for follow up. No other education was provided outside usual care in the ED.

Measures

For all participants in both arms, we collected survey data at 12 weeks, with data recorded into a Qualtrics® database. We assessed follow-up outcomes via a web-based survey sent as a text message link. If no online survey was completed, trained research staff performed phone follow up approximately 7 days after the online survey web link was sent. For those participants who did not complete the online survey, staff attempted to reach participants approximately twice a week for 4-8 weeks, with two additional emails sent with the survey link. In-person follow-up in the ED was conducted if the participant returned to the ED for additional medical care.

We focused on 4 of Proctors’ health service implementation measurements.25,27 Feasibility is the extent to which an innovation can be used in a setting. Data for this measure included rates of refusal to participate and loss-to-follow-up. Acceptability is the extent to which the innovation is agreeable to a stakeholder and was assessed using quantitative data, including if the participant “liked” the program (along a Likert scale) and would recommend it to peers. Adoption, which is the intention or decision to use the intervention, was also measured by assessing interactivity. We defined interactivity as the proportion of text message responses from the 18 interactive text message algorithms. The mobile platform recorded web links clicked. Lastly, fidelity is the extent to which an intervention is used as intended. Data for this included proportion of opt outs and triggered LIVE Office Hours, as well as how many intervention participants failed to receive any text messages. Data for the adoption and fidelity outcomes came directly from our mobile platform provider.

Our primary efficacy outcome was self-report of highly effective contraception initiation. Secondary outcomes included intentions to initiate contraceptives, any sexual intercourse, pregnancy, condom and emergency contraception use, and follow up to medical care.28 All data for secondary outcomes were collected via self-report from follow-up online surveys or telephone follow-up. Self-report is the standard method used to assess technology-based SRH outcomes, as noted in a recent meta-analysis.9 We chose not to use an electronic medical record (EMR) review to assign outcomes, as we have found in prior studies that EMR documentation of the receipt of a prescription for a birth control method does not necessarily equate with actual initiation and that an EMR review does not capture information from outside our medical center.29

Analysis

As this was a pilot trial, the sample size was determined based on feasibility rather than to provide adequate power to detect a minimal clinically meaningful effect.30 We planned to enroll 250 patients over 2 years. Accounting for a 20% lost to follow up rate, if the proportion of participants who initiated contraception for the intervention and control arms ranged between 15% and 25%, 250 participants would have enabled us to construct a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference of two proportions with width no greater than 25%. Based on prior studies, we considered that 100 participants would be adequate to properly determine our implementation outcome.31,32

We generated descriptive statistics to summarize data related to implementation outcomes. We analyzed both an intention-to-treat (ITT) population and per-protocol population for efficacy outcomes. For the ITT analysis, the primary outcome of contraception initiation for those lost to follow-up was imputed conservatively as contraception not initiated. We also performed an ITT analysis using only those who completed follow up. We also analyzed a per-protocol population which included participants who received at least one text, responded to at least one text, and did not opt out; for this analysis, we did not impute outcomes. For secondary outcomes, we analyzed those in the ITT population who completed follow up.

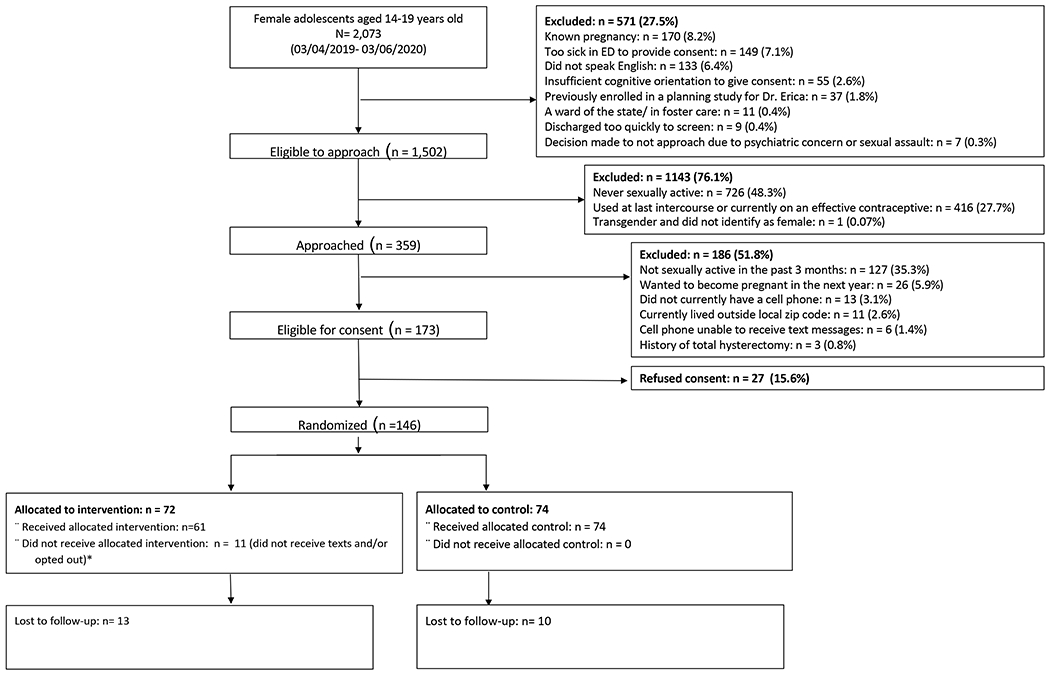

RESULTS

From March 2019 to March 2020, we enrolled and randomized 146 participants to the intervention (n=72) and control (n=74) arms (Figure 2). Enrollment ended early due to COVID-19. Participants were predominantly Hispanic (125/144; 86.8%) and had primary care providers (114/142; 80.2%) (Table 1). The mean age was 17.74 (Standard Deviation (SD)+/−1.27) years. There were no statistical differences between arms except that more participants in the intervention arm (67.6%) than in the control arm (48.6%) had ever used an effective birth control method in the past (p=0.02). All participants aged 14-17 years (n=54; 37.0%) were consented with a waiver of parental consent.

Figure 2.

CONSORT Diagram. Two participants who did not receive allocated intervention were lost to follow up.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of intervention and control arm (n=143). Two intervention participants (age 16 and 19) and one control participant (age 17) did not have their baseline data recorded due to a technical issue and are therefore not included in this table.

| Intervention n (%) n= 71 | Control n (%) n= 72 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 14-17 | 29 (40.3) | 25 (33.8) |

| 18-19 | 43 (59.7) | 49 (66.2) |

| Race | ||

| African American | 20 (28.6) | 14 (19.4) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 3 (4.2) |

| White | 2 (2.8) | 4 (5.6) |

| Other | 39 (53.9) | 40 (55.6) |

| I don’t know or don’t want to answer that | 8 (11.3) | 9 (12.5) |

| Hispanic | 62 (87.3) | 63 (86.3) |

| Medical care | ||

| Has regular doctor or other source of health care | 57 (80.3) | 57 (79.2) |

| Presenting to the ED with a sexual and/or reproductive health chief complaint | 23 (32.4) | 24 (33.3) |

| Birth control use and intentions | ||

| Ever thought about starting a birth control method | 52 (73.2) | 48 (66.7) |

| Seriously considering starting a birth control method in the next 6 months | 30 (42.3) | 28 (38.9) |

| Planning on starting a birth control method in the next 30 days | 15 (21.1) | 14 (19.4) |

| If going to start a birth control method in the future, has chosen what method she would start | 38 (53.5) | 33 (45.8) |

| If the ED could provide birth control, would you be interested in started one today? | ||

| Yes | 20 (28.2) | 19 (26.4) |

| No | 33 (46.5) | 28 (38.9) |

| I’m not sure | 18 (25.4) | 23 (31.9) |

| Did not answer | 0 (0) | 2 (2.8) |

| Ever used a birth control method | 48 (67.6) | 35 (48.6) |

| Ever talked to a doctor/nurse about starting a birth control method | 48 (67.6) | 41 (56.9) |

| Ever had a class on sexual education | 60 (84.5) | 61 (84.7) |

| Sexual behaviors | ||

| In the past 3 months, how many people have you had sexual intercourse with? | ||

| 1 only | 62 (87.3) | 61 (84.7) |

| 2 or more | 9 (12.7) | 11 (15.3) |

| Sexual partners | ||

| Men only | 63 (88.7) | 65 (90.3) |

| Women only | 1 (1.4)* | 0 |

| Both women and men | 7 (9.9) | 7 (9.7) |

| Pregnant once or more in her lifetime | 11 (15.5) | 11 (15.1) |

| Currently in a relationship | 56 (78.9) | 56 (77.8) |

| Consistent condom use (“every time”) | 13 (18.3) | 10 (13.9) |

| Condom use at last sexual intercourse | 25 (35.2) | 18 (25) |

| Lifetime emergency contraception use | ||

| 0 times | 27 (38) | 24 (33.3) |

| 1 time | 18 (25.4) | 14 (19.4) |

| More than 2 times | 23 (32.4) | 33 (45.8) |

| I don’t understand what emergency contraception is | 3 (4.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| Pregnancy intentions | ||

| Trying hard to prevent pregnancy | 44 (62) | 38 (52.8) |

| Very much do not want to get pregnant now | 57 (80.3) | 61 (84.7) |

| Planning to not get pregnant | 64 (90.1) | 66 (91.7) |

Despite inclusion criteria being sex with a man, one participant answered only sex with women. She remained in the analysis.

Implementation

Table 2 summarizes the results for the implementation outcomes. Overall, 121 (82.9%) completed follow-up, with 15 (20.8%) and 10 (13.5%) lost to follow-up in the intervention and usual care arms, respectively. Of the 18 interactive algorithms, 40.2% (29/72) of the participants interacted with at least 25% of them, 23.6% (17/72) interacted with at least 50%, and 8.3% (6/72) interacted with at least 75%. Although individual click data were not available, the most popular links were our Instagram® cartoons (34) and the www.dr-erica.com website (32).

Table 2.

Implementation Outcomes

| Implementation outcomes | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Feasibility | |

| Participants enrolled of those eligible for enrollment (n=173) | 146 (84.4) |

| Completed follow up among all those enrolled (n=146) | 121 (82.9) |

| Acceptability * | |

| Liked messages (n=49) | 48 (98.0) |

| Read more than half of messages (n=49) | 41 (83.7) |

| Would recommend Dr. Erica to friends (n=49) | 41 (83.7) |

| Adoption ** | |

| Interactive with one or more text (n=72) | 63 (87.5) |

| Total number of web links clicked among intervention participants (n=72) | 289 |

| Fidelity ** | |

| Opted out (n=72) | 5 (6.9) |

| LIVE Office Hours triggered by participant texts (n=72) | 14 (19.4) |

| Failed to receive any text messages | 1 (1.4) |

49 is the number of participants in the intervention arm who answered these questions.

72 is the total number of participants in the intervention arm.

Texts from 1 in 8 intervention participants (12.5%) triggered an invitation to LIVE Office Hours. Examples of such texts included “I’m 8 days late of my period! What should I do?” and “Where can I get some [free condoms]?” An investigator (LC) interacted and answered questions via live text messaging with that subgroup.

Efficacy: Primary Outcome

In the ITT population with imputed outcomes, 19.4% (14/72) in the intervention arm and 18.9% (14/74) in the usual care arm initiated contraception [absolute risk difference (ARD) = 0.5%, 95% CI −12.3%, 13.3%], imputing “contraception not initiated” for those lost to follow-up. Among the ITT who completed follow up without imputed outcomes, 24.6% (14/57) in the intervention versus 21.9% (14/64) in the usual care arm initiated contraceptives [absolute risk difference (ARD) =2.7%, 95% CI −12.4%, 17.8%].

For the per protocol analysis, among the 72 females in the intervention arm, 5 (6.9%) did not reply to any text messages and opted out, 4 (5.6%) replied to no text messages, and 2 (2.8%) replied to text messages but subsequently opted out. Of the 63 who received the intervention as intended, 13 were lost to follow up, leading to a per-protocol population of 48 in the intervention group. Twenty-seven percent (13/48) of the per-protocol intervention arm initiated contraceptives, while twenty-two percent (14/64 who completed follow-up) of the per-protocol control arm initiated contraceptives.

Efficacy: Secondary Outcomes

Table 3 displays the results among those in the ITT arm who completed follow up. Females in the intervention arm were more likely to choose which birth control method they would start if there were going to start a method in the future [65.9% (27/41) vs. 30.0% (15/50); ARD 35.9%, 95% CI 16.6%, 55.1%] and less likely to use emergency contraception than those in the usual care arm [13.1% (5/38) vs. 34.0% (17/40); ARD −20.9%, 95% CI −37.8%, −3.9%].

Table 3.

Efficacy outcomes among the ITT arm who completed follow up. Denominator represents those who completed follow up and answered that question.

| Efficacy Outcomes | Intervention % (n/N) | Control % (n/N) | Absolute Risk Difference [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMARY | |||

| Highly effective contraception initiation | 24.6 (14/57) | 21.9 (14/64) | 2.69 [−12.4, 17.8] |

| SECONDARY | |||

| Any sex over the past 3 months | 79.6 (39/49) | 83.0 (49/59) | −3.4 [−18.3, 11.3] |

| Pregnancy | 5.1 (2/39) | 6.1 (3/49) | −1.0 [−10.6, 8.6] |

| Consistent condom use | 25.6 (10/39) | 18.4 (9/49) | 7.2 [−10.2, 24.7] |

| Condom use at last intercourse | 53.8 (21/39) | 55.1 (27/49) | −1.2 [−22.2, 19.7] |

| Emergency contraception use | 13.1 (5/38) | 34.0 (17/50) | −20.9 [−37.8, −3.9] |

| Follow up to medical care | 67.3 (35/52) | 72.4 (42/58) | −5.1 [−22.3, 12.1] |

| Intentions to use contraception among those who did not start a birth control method | |||

| Thought about starting a birth control over the past 3 months | 71.4 (30/42) | 58.0 (29/50) | 13.4 [−5.9, 32.7] |

| Seriously considering starting a birth control method in the next 6 months | 59.5 (25/42) | 42.0 (21/50) | 17.5 [−2.7, 37.7] |

| Seriously considering starting a birth control method in the next 30 days | 22.0 (9/41) | 12.0 (6/50) | 10.0 [−5.6, 25.5] |

| Choose what method she would start if she was to start in the future | 65.9 (27/41) | 30.0 (15/50) | 35.9 [16.6, 55.1] |

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that Dr. Erica was feasible to implement in the ED setting with those who were eligible for enrollment consenting to participation and low rates of loss to follow-up. Dr. Erica was well-received by participants, who engaged with the program, responding to texts and clicking on websites. This suggests that the next step would be definitive efficacy testing, as the program showed potential to move participants to the planning stages of contraception decision making.

This study strengthens the evidence that digital health interventions have the potential to be successfully implemented in the ED setting. Prior ED-based interventions successfully used technology to screen, intervene, and refer at-risk patients, and there are specific reasons why such interventions might have succeeded.33,34 First, digital interventions remove the burden from medical providers of delivering preventive health. Similar to ED-based computerized interventions, Dr. Erica converted traditional face-to-face counseling into technology-delivered evidence-based education.35 While health educators or social workers can provide thoughtful SRH guidance, ancillary ED staff are often over-loaded with other time-consuming responsibilities. Digital interventions, whether fully automated or guided by additional human support, shift the responsibility away from the primary ED care team, while still addressing the unmet preventive health care needs of the most vulnerable patients.25 An example of this is the LIVE Office Hours feature of the Dr. Erica program. This function allowed participants to ask questions but receive responses in a manner that did not necessitate an ED or research team member to monitor the chatline. Instead, questions were answered during “office hours” which were pre-determined blocks of time. Such methodology allows for scalability, using existing personnel outside the ED who have relevant expertise to respond to questions.

Interventions such as Dr. Erica were designed to minimize interruption of ED patient flow. Many other prior technology-based interventions delivered computer-based modules during the ED visit, while the bulk of Dr. Erica delivery occurred after the ED visit and minimized the time spent occupying a room or a private space.35 Yet, interventions like Dr. Erica still aim to extend a patient’s motivation to change their behaviors after the ED visit rather than taking a one-and-done approach. The Sentinel Event Model is one which describes how an ED visit can spark an internal drive to change behavior, such as chest pain might lead to the motivation to cease smoking.36 By prolonging an ED intervention after that initial ED visit, interventions like Dr. Erica spread the behavioral health message over time, reaching participants during moments when the sexual behavior might occur and providing real-time education and advice when the need is the greatest.37

The high acceptability of Dr. Erica likely reflects the user-centered design process we employed for its development. This multi-stage process included end-users, such as patients, as a central focus of the design.38 Similar to iDov, a text messaging program for adolescent ED patients with depression, Dr. Erica provided two-way text messages as a means to augment interactivity and mimic a digital conversation.39 This automated technology may be scalable to a larger population without an increased need for resources. However, one must keep in mind that interventions must appreciate the cultural and contextual differences among our adolescent patients. As a result, interventions need to be tailored accordingly.40

Although this was pilot trial and our intervention did not significantly impact contraceptive rates within 3 months, it did appear to impact intentions to use contraceptives in the future, including choosing a future method. This is promising as psychiatry research demonstrates that prompting people to develop a plan, such as “When situation x arises, I will implement response y,” increases attainment of a goal.41 Such a plan, or an “implementation intention,” can trigger an association between a behavior and concrete future moment.42 Therefore, identifying methods to move an adolescent who is willing and ready to initiate contraceptives from the planning stage to the action stage and, in turn, allow her to overcome potential barriers to contraception initiation, may be a central component in potential modifications for our intervention.

One interesting and unexpected finding in the trial was the increased use of emergency contraception in the usual care arm compared to the intervention arm. A few possible reasons may help explain this finding. Among those in the usual care arm, the frequent use of emergency contraception may reflect less knowledge of its intended use.43 Among those in the intervention arm, it also may reflect more often using contraceptives with intercourse and having less of a need for emergency contraception. Conversely, less use of emergency contraception the intervention arm might signify a lack of knowledge and, therefore, use. Further studies are needed to confirm this finding.

LIMITATIONS

First, this study was conducted at a single center and represents a predominantly Hispanic population. Second, our intervention was available in only English. Third, participants did not respond to all follow-up questions, which may have affected our findings. Fourth, while there was not clear evidence that outcome missingness depended on any key variables of interest, the ITT analysis using only those who completed follow up had the potential to introduce bias; this will be addressed in the subsequent larger trial. Fifth, our primary outcome was effective contraception initiation; future studies might include patient-centered outcomes that reflect the complexities of contraception decision making and perception of pregnancy.44 Sixth, as this was a pilot study, we did not adjust for factors that differed between groups and may affect the results. Lastly, this manuscript describes implementation factors focusing more on the user; future work will focus more on the provider and system.

CONCLUSION

Dr. Erica is a personalized and interactive multi-media text messaging intervention that demonstrated feasibility and acceptability, with high adoption and fidelity. The program synthesizes evidence-based SRH education into a compact theory-based intervention targeting adolescent ED patients. Dr. Erica was designed to be scalable, with the goal to deliver evidence-based SRH education. While more data are needed to determine the effectiveness of Dr. Erica, this study serves as an example of how user-centered, theory-based digital interventions might be used in an ED setting.

Financial support:

Dr. Chernick was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through grant number KL2TR001874 and by the National Institute of Child and Health Development, through grant 1K23HD096060-01.

Role of Funder:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations:

- (ED)

emergency department

- (US)

United States

- (Dr. Erica)

Emergency Room Interventions to improve the Care of Adolescents

- (Depo-Provera or medroxyprogesterone acetate)

shot

- (NuvaRing)

ring

- (Ortho Evra)

transdermal patch

- (SCT)

Social Cognitive Theory

- (MI)

Motivational Interviewing

- (BITs)

behavioral intervention technologies

Footnotes

Presentations: This work was presented at the 2020 Pediatric Academic Society Meeting (virtual conference) as a platform presentation.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have nothing to disclose.

Trial Registration: NCT3866811

REFERENCES

- 1.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1998;101(6):987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schappert SM, Rechtsteiner EA. Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(8)(8):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson ES, Hsieh D, Alter HJ. Social Emergency Medicine: Embracing the Dual Role of the Emergency Department in Acute Care and Population Health. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(1):21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller MK, Chernick LS, Goyal MK, et al. A Research Agenda for Emergency Medicine–based Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chernick L, Chun T, Richards R, Bromber J, et al. Sex without contraceptives in a multi-center study of adolescent emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. Apr;27(4):283–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad FA, Jeffe DB, Carpenter CR, et al. Emergency Department Directors Are Willing to Expand Reproductive Health Services for Adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32(2):170–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon M, Badolato GM, Chernick LS, Trent ME, Chamberlain JM, Goyal MK. Examining the Role of the Pediatric Emergency Department in Reducing Unintended Adolescent Pregnancy. J Pediatr. 2017;189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chernick LS, Westhoff C, Ray M, et al. Enhancing Referral of Sexually Active Adolescent Females from the Emergency Department to Family Planning. J Women’s Heal. 2015;24(4):324–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widman L, Nesi J, Kamke K, Choukas-Bradley S, Stewart JL. Technology-Based Interventions to Reduce Sexually Transmitted Infections and Unintended Pregnancy Among Youth. J Adolesc Heal. 2018;62(6):651–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ybarra M, Goodenow C, Rosario M, Saewyc E, Prescott T. An mHealth intervention for pregnancy prevention for LGB teens: An RCT. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tebb KP, Rodriguez F, Pollack LM, et al. Improving contraceptive use among Latina adolescents: A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating an mHealth application, Health-E You/Salud iTu. Contraception. 2021. Mar 17; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chernick LS, Stockwell MS, Gonzalez A, et al. A User-Informed, Theory-Based Pregnancy Prevention Intervention for Adolescents in the Emergency Department: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Adolesc Heal. 2021. Apr;68(4):705–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trussell J Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contracept Technol. 2004;70:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oregon Foundation of Reproductive Health. One key question ® in primary care. Found in https://www.orpca.org/Symposia/OKQ_OPCA_4_2015_2.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2021.

- 16.Research Randomizer. https://www.randomizer.org/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 17.Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system - 2013. MMWR Recomm Reports. 2013;62(1):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Survey of Family Growth. Found in https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2015_2017_puf.htm. Accessed May 30, 2021.

- 19.Bartholomew LK; Parcel GS; Kok G et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 3rd ed. Jossey Bass Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douaihy A; Kelly TM; Gold M Motivational Interviewing. 1st ed. New York: Oxford Universit Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A Social Foundataions of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chernick LS, Berrigan M, Gonzalez A, et al. Engaging Adolescents With Sexual Health Messaging: A Qualitative Analysis. J Adolesc Heal. 2019:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingle BR. Introduction to design thinking. In: Design Thinking for Entrepreneurs and Small Businesses. Berkeley, CA: Apress; 2013:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.University of California San Francisco. Beyond the Pill. Found at https://beyondthepill.ucsf.edu/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 25.Hermes EDA, Lyon AR, Schueller SM, Glass JE. Measuring the Implementation of Behavioral Intervention Technologies: Recharacterization of Established Outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e11752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitz N, Wood E, Kantor L. The influence of technology delivery mode on intervention outcomes: Analysis of a theory-based sexual health program. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(8):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Orr MG, Finer LB, Speizer I. Toward a multidimensional measure of pregnancy intentions: Evidence from the United States. Stud Fam Plann. 2009;40(2):87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chernick LSL, Stockwell MMS, Wu M, et al. Texting to Increase Contraceptive Initiation Among Adolescents in the Emergency Department. J Adolesc Heal. 2017;61(6):786–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How We Design Feasibility Studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ranney ML, Freeman JR, Connell G, et al. A depression prevention intervention for adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Heal. 2016;59(4):401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suffoletto B, Akers A, McGinnis KA, Calabria J, Wiesenfeld HC, Clark DB. A sex risk reduction text-message program for young adult females discharged from the emergency department. J Adolesc Heal. 2013;53(3):387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora S, Peters AL, Burner E, Lam CN, Menchine M. Trial to examine text message-based mhealth in emergency department patients with diabetes (TExT-MED): A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(6):745–754.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Callaway C, et al. A text message alcohol intervention for young adult emergency department patients: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(6):664–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a Brief Intervention for Reducing Violence and Alcohol Misuse Among Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boudreaux ED, Bock B, O’Hea E. When an event sparks behavior change: An introduction to the sentinel event method of dynamic model building and its application to emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(3):329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birnbaum F, Lewis D, Rosen RK, Ranney ML. Patient engagement and the design of digital health. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):754–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ranney ML, Pittman SK, Dunsiger S, et al. Emergency department text messaging for adolescent violence and depression prevention: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychol Serv. 2018;15(4):419–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandler R, Guillaume D, Parker A, Wells J, Hernandez ND. Developing Culturally Tailored mHealth Tools to Address Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes Among Black and Latina Women: A Systematic Review. Health Promot Pract. 2021;Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milkman KL, Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. Using implementation intentions prompts to enhance influenza vaccination rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(26):10415–10420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta-analysis of Effects and Processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38(06):69–119. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cleland K, Marcantonio TL, Hunt ME, Jozkowski KN. “It prevents a fertilized egg from attaching…and causes a miscarriage of the baby”: A qualitative assessment of how people understand the mechanism of action of emergency contraceptive pills. Contraception. 2021;103(6):408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aiken AR, Borrero S, Callagari LS, Dehlendoft C. Rethinking the Pregnancy Planning Paradigm: Unintended Conceptions or Unrepresentative Concepts? Perspct Sex Reprod Health. 2016. Sep;48(3):147–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]