Abstract

The beta-hemolytic group G Streptococcus clinical isolate BM2721 was resistant to high levels of aminoglycosides by synthesis of AAC(6′)-APH(2"), APH(3′)-III, and ANT(6) modifying enzymes. The corresponding genes were found to be adjacent as the result of a recombination event between Tn4001 and Tn5405, two transposons originating in staphylococci.

Group G streptococci form a heterogeneous collection of microorganisms. A minimum of three groups can be distinguished, as follows: (i) the large-colony beta-hemolytic group G streptococci isolated from humans, (ii) the large-colony beta-hemolytic strains from animals, designated Streptococcus canis, that differ from human group G strains by their fibrinolytic activity (13), and (iii) the minute beta-hemolytic colony group G strains from humans. Human large-colony group G streptococci have been mainly associated with pharyngitis, skin and soft tissue infections, septicemia, endocarditis, and arthritis (12). They can also be involved in neonatal and postpartum infections, as well as infections in immunosuppressed or neutropenic patients (21). These streptococci, which are closely related to group L strains, the beta-hemolytic group C Streptococcus equisimilis, and the alpha-hemolytic group C strains have not been assigned a species name because of their biochemical heterogeneity (4).

The antibiotic susceptibility of human large-colony group G strains is similar to that of Streptococcus pyogenes. Although resistance to chloramphenicol, macrolides, and tetracyclines may occur (9), penicillin G (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC], ≤0.01 μg/ml) is consistently active against these streptococci. High-level resistance to gentamicin (MIC, ≥1,000 μg/ml) has been detected among gram-positive cocci of clinical importance (1, 11) but, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been reported for human large-colony group G streptococci.

Composite transposons conferring resistance to nearly all available aminoglycosides have been found on plasmids and in the chromosome of staphylococci. Tn4001 (6, 16) is flanked by two copies of IS256 (2), in opposite orientations, and carries the aac(6′)-aph(2") gene which encodes the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase-2"-O-phosphotransferase enzyme (5). Tn5405 (3) is delimited by two inverted copies of IS1182 and carries the aph(3′)-III and the ant(6) genes which encode aminoglycoside 3′-O-phosphotransferase (7, 20) and 6-O-adenylyltransferase (15) activities, respectively. High-level resistance to aminoglycosides in Streptococcus group G is of clinical importance, since combination of penicillin G with an aminoglycoside has been recommended for severely ill patients, especially for endocarditis.

Streptococcus BM2721 was isolated in November 1995 from a cutaneous infection at the Hôpital Saint Michel in Paris. After overnight growth on blood agar, strain BM2721 formed large colonies exhibiting beta-hemolysis, and displayed Lancefield group G antigen, as detected by the Streptex kit (Murex Diagnostics Limited, Dartford, England).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by disk diffusion on Mueller-Hinton agar (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) containing 5% (vol/vol) horse blood, and high-level resistance to aminoglycosides was tested with disks containing 250 μg of gentamicin, 1,000 μg of kanamycin, and 500 μg of streptomycin (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur). Strain BM2721 was also resistant to tetracyclines and minocycline, to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics, to fusidic acid, and to rifampin. The MICs of amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and streptomycin against BM2721, determined by dilution in Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% horse blood with an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot (19), were >1,000 μg/ml.

Analysis of crude extracts from BM2721 by the phosphocellulose paper-binding assay (8) with [1-14C]acetyl-coenzyme A, [U-14C]ATP ammonium salt, and [γ-32P]ATP triethylammonium salt (Amersham Radiochemical Center, Amersham, England) as cofactors indicated that high-level aminoglycoside resistance in BM2721 was due to production of aminoglycoside-acetyltransferase, -adenylyltransferase, and -phosphotransferase activities (data not shown).

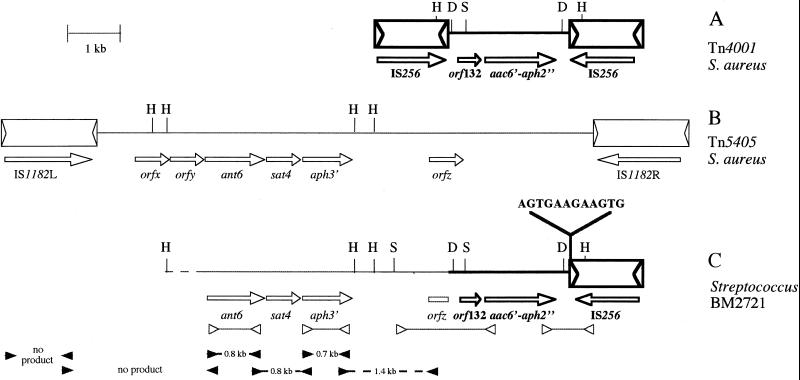

Total DNA from BM2721 digested with HindIII was fractionated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose sheet (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany), and hybridized sequentially to 32P-labeled aac(6′)-aph(2") and IS256 probes. A HindIII site in each copy of IS256 delineates a central 2.5-kb fragment containing the gentamicin resistance determinant (Fig. 1A). A 3.2-kb HindIII fragment from BM2721 DNA hybridized with both probes, and only two HindIII fragments hybridized with the IS256 probe (data not shown). These results indicated that IS256 was present in a single copy adjacent to the aac(6′)-aph(2") gene (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the genomic environment of the aminoglycoside resistance genes of Streptococcus BM2721 to Tn4001 (16) and Tn5405 (3) from Staphylococcus aureus. (A) Physical map of Tn4001 (thick line). The inverted copies of IS256 are represented by open boxes, and the arrowheads indicate the 26-bp imperfect terminal inverted repeats. (B) Physical map of Tn5405 (thin line). The arrowheads within IS1182 indicate the 8-bp imperfect terminal inverted repeats. (C) Organization of the aminoglycoside resistance region of Streptococcus BM2721. Open arrowheads correspond to the primers used for sequencing. Closed arrowheads correspond to the primers used for PCR mapping, and the numbers indicate the sizes of the amplicons. Open arrows indicate the directions of transcription. D, DraI; H, HindIII; S, SspI.

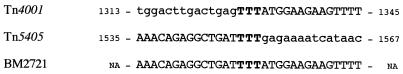

The regions flanking the aac(6′)-aph(2") gene in BM2721 were explored by PCR and inverted PCR with a DNA Thermal Cycler (model 2400; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.), cloning, and sequencing. Double-stranded DNA sequencing was performed by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (18). The boundaries of the regions flanking the aac(6′)-aph(2") gene in BM2721 were found to be identical to an internal portion of Tn4001. The 129 bp downstream from the resistance gene were identical to those in Tn4001 except for a 12-bp insertion upstream from IS256 (Fig. 1C). Upstream from aac(6′)-aph(2"), the identity with Tn4001 was interrupted 67 bp upstream from open reading frame 132 (position 1328 in Tn4001, numbering according to GenBank accession no. M18086). The 608-bp sequenced fragment upstream from that site was found to be identical to a portion of Tn5405 (positions 945 to 1552 in Tn5405, numbering according to GenBank accession no. U73027) (Fig. 1B). The genetic organization in BM2721 may be the result of a recombination event that occurred between the left part of Tn5405 within orfz and the right part of Tn4001 (Fig. 1C). Three adjacent thymidines, likely to be implicated in this event, were found in Tn4001, in Tn5405, and in BM2721 DNA (Fig. 2). The region upstream from orfz in BM2721 was mapped by PCR with pairs of primers specific for orfz (3), aph(3′)-III (20), ant(6) (15), and IS1182 (3). The sizes of the amplicons obtained indicated that the ant(6), aph(3′)-III, and orfz genes had the same relative position in BM2721 as in Tn5405 (Fig. 1B and C). However, IS1182 was not detected in BM2721 DNA. It thus appears that, in BM2721, a deletion stabilized the new genetic element generated by recombination.

FIG. 2.

Site of recombination between Tn5405 and Tn4001 in BM2721. The sequences of Tn4001 between nucleotides 1313 and 1345 (numbering according to GenBank accession no. M18086) and of Tn5405 between nucleotides 1535 and 1567 (numbering according to GenBank accession no. U73027) were aligned with that of BM2721. Identities are indicated in capital letters. The three thymidines present in the three sequences and probably implicated in the recombination event are shown in boldface type. NA, not applicable.

Conjugation experiments from Streptococcus BM2721 to Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 (10) were carried out on membrane filters (17) with selection on bile-esculin medium supplemented with 500 μg of gentamicin per ml. No transconjugants were obtained, and all attempts to isolate plasmid DNA from BM2721 were unsuccessful (17). Total DNA of BM2721 digested with SmaI or I-CeuI, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for rRNA genes (14), was fractionated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate buffer with a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophoresis apparatus (CHEF-DRIII system; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) under the following conditions: initial pulse, 60 s; final pulse, 120 s; voltage, 6 V/cm; time of electrophoresis, 24 h; included angle, 120°; and temperature, 14°C. The DNA fragments were transferred to a nitrocellulose sheet (Nytran) and hybridized successively to 32P-labeled aph(3′)-III and 16S rRNA (rrs) probes. The rrs probe hybridized with the four I-CeuI-generated fragments. By contrast, the aph(3′)-III probe produced a strong hybridization signal with the DNA that remained in the well, but did not hybridize with the four fragments resolved in the gel (data not shown). These observations suggest that the resistance determinant is not part of the chromosome. The aph(3′)-III probe, but not the rrs probe, hybridized with a ca. 150-kb SmaI fragment, consistent with the fact that the resistance gene was carried by a plasmid with a minimum size of 150 kb.

Emergence of high-level resistance to aminoglycosides in group G Streptococcus BM2721 was due to acquisition of the aac(6′)-aph(2"), aph(3′)-III, and ant(6) genes as part of a new genetic element resulting from recombination of two transposons that are widespread in staphylococci. The truncated transposon-like element was carried by a large plasmid which does not conjugate to or replicate in enterococci. To the best of our knowledge, high-level gentamicin resistance in beta-hemolytic pyogenic streptococci had not yet been reported.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Bristol-Myers Squibb unrestricted biomedical research grant in infectious diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buu-Hoï A, Le Bouguenec C, Horaud T. High-level chromosomal gentamicin resistance in Streptococcus agalactiae (group B) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:985–988. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne M E, Rouch D A, Skurray R A. Nucleotide sequence analysis of IS256 from Staphylococcus aureus gentamicin-tobramycin-kanamycin-resistance transposon Tn4001. Gene. 1989;81:361–367. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derbise A, Aubert S, El Solh N. Mapping the regions carrying the three contiguous antibiotic resistance genes aadE, sat4, and aphA-3 in the genomes of staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1024–1032. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrow J A E, Collins M D. Taxonomic studies on streptococci groups C, G and L and possibly related taxa. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1984;5:483–493. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferretti J J, Gilmore K S, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the gene specifying the bifunctional 6′-aminoglycoside acetyltransferase 2"-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase enzyme in Streptococcus faecalis and identification and cloning of gene regions specifying the two activities. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:631–638. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.2.631-638.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillespie M T, Lyon B R, Messerotti L J, Skurray R A. Chromosome- and plasmid-mediated gentamicin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus encoded by Tn4001. J Med Microbiol. 1987;24:139–144. doi: 10.1099/00222615-24-2-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray G S, Fitch W M. Evolution of antibiotic resistance genes: the DNA sequence of a kanamycin resistance gene from Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Biol Evol. 1983;1:57–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas M J, Dowding J E. Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 1975;43:611–628. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)43124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horodniceanu T, Bougueleret L, Bieth G. Conjugative transfer of multiple-antibiotic resistance markers in beta-hemolytic group A, B, F, and G streptococci in the absence of extrachromosomal deoxyribonucleic acid. Plasmid. 1981;5:127–137. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(81)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob A E, Hobbs S J. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:360–372. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.360-372.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufhold A, Potgieter E. Chromosomally mediated high-level gentamicin resistance in Streptococcus mitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2740–2742. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.12.2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam K, Bayer A S. In vitro bactericidal synergy of gentamicin combined with penicillin G, vancomycin, or cefotaxime against group G streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:260–262. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.2.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lammler C, Frede C, Gurturk K, Hildebrand A, Blobel H. Binding activity of Streptococcus canis for albumin and other plasma proteins. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2317–2323. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-8-2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S H, Hessel A, Sanderson K E. Genomic mapping with I-Ceu I, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6874–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ounissi H, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequences of streptococcal genes. In: Ferretti J J, Curtiss III R, editors. Streptococcal genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouch D A, Byrne M E, Kong Y C, Skurray R A. The aacA-aphD gentamicin and kanamycin resistance determinant of Tn4001 from Staphylococcus aureus: expression and nucleotide sequence analysis. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3039–3052. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-11-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsh E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steers E, Foltz E L, Gravies B S, Riden J. An inocula replicating apparatus for routine testing of bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. Antibiot Chemother (Basel) 1959;9:307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trieu-Cuot P, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus faecalis plasmid gene encoding the 3′5"-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase type III. Gene. 1983;23:331–341. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vartian C, Lerner P I, Shlaes D M, Gopalakrishna K V. Infections due to Lancefield group G streptococci. Medicine. 1985;64:75–88. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]