Abstract

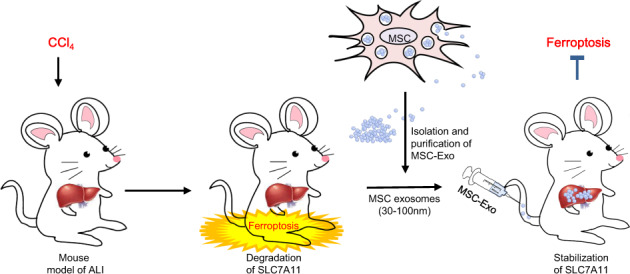

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have attracted interest for their potential to alleviate liver injury. Here, the protective effect of MSCs on carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced acute liver injury (ALI) was investigated. In this study, we illustrated a novel mechanism that ferroptosis, a newly recognized form of regulated cell death, contributed to CCl4-induced ALI. Subsequently, based on the in vitro and in vivo evidence that MSCs and MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) treatment achieved pathological remission and inhibited the production of lipid peroxidation, we proposed an MSC-based therapy for CCl4-induced ALI. More intriguingly, treatment with MSCs and MSC-Exo downregulated the mRNA level of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2) and lipoxygenases (LOXs) while it restored the protein level of SLC7A11 in primary hepatocytes and mouse liver, indicating that the inhibition of ferroptosis partly accounted for the protective effect of MSCs and MSC-Exo on ALI. We further revealed that MSC-Exo-induced expression of SLC7A11 protein was accompanied by increasing of CD44 and OTUB1. The aberrant expression of ubiquitinated SLC7A11 triggered by CCl4 could be rescued with OTUB1-mediated deubiquitination, thus strengthening SLC7A11 stability and thereby leading to the activation of system XC− to prevent CCl4-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis. In conclusion, we showed that MSC-Exo had a protective role against ferroptosis by maintaining SLC7A11 function, thus proposing a novel therapeutic strategy for ferroptosis-induced ALI.

Subject terms: Hepatotoxicity, Experimental models of disease

Schematic diagram of the protective effect of MSC-derived exosomes on maintaining SLC7A11 function during ferroptosis involved in CCl4-induced ALI.

Introduction

The liver has antibacterial/antiviral and drug detoxification functions and plays a central role in regulating homeostasis [1]. Acute liver injury (ALI) is one of the most prominent causes of liver diseases and is associated with high morbidity and mortality [2]. A variety of hepatotoxic factors, including viruses, lipid deposition, and drugs, can induce ALI, and 3.5% of deaths worldwide result from liver diseases [3, 4]. Therefore, it is crucial to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of ALI and to develop appropriate therapeutic strategies. Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is a typical hepatotoxic compound that is widely used to induce the ALI model for mechanism research [5]. Herein, we aimed to explore the potential mechanisms of ALI using a CCl4-induced mouse model and to explore possible effective treatment strategies.

Much attention has been focused on applying mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in biomedicine based on their potential in promoting liver regeneration and repairing liver injury. MSCs are a heterogeneous subset of stromal cells that can be easily isolated from adipose, bone marrow, and synovial tissues and can subsequently differentiate into numerous cell lineages according to specific biomedical applications. The immunological properties of MSCs, including their immune-regulatory, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive abilities, suggest a potential role in immune tolerance [6]. Due to these properties, MSCs are considered ideal cell sources for tissue regeneration. Previously, we showed that MSCs transplantation attenuated CCl4-induced ALI by modulating the hepatic immune system [7]. Initial research suggested that MSCs exerted their therapeutic effects by engrafting to the site of injury. However, further studies showed that only a small percentage of injected MSCs reached their targets, whereas extracellular vesicles such as exosomes released by MSCs have vital and beneficial effects during treatment [8, 9]. In addition, exosomes released from MSCs contain special types of RNAs, lipids, and proteins, which are prerequisites for physiological homeostasis, cell proliferation, and tissue regeneration [10, 11]. Thus, we envision that MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) exhibit similar functions as MSCs and can be applied as MSC-based cell-free therapy.

In this study, CCl4 not only induced acute injury but simultaneously promoted ferroptosis in the liver. The hepatotoxic effects of CCl4 were related to its metabolic conversion in the liver to reactive intermediates. In addition, lipid peroxidation stimulation was observed in the liver shortly after administering CCl4 to mice in vivo. Of note, a high accumulation of products from lipid peroxidation initiated ferroptosis. In addition, various studies suggested that ferroptosis might be a new type of cell death associated with liver diseases such as viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and hemochromatosis [12–15].

Ferroptosis is a newly identified form of regulated cell death driven by perturbation of the glutathione (GSH)-dependent lipid-hydroperoxide-scavenging network [16, 17]. Lipid peroxidation is regulated by system XC−, which transports glutamate out of the cell in exchange for the transport of cysteine, an important precursor for GSH synthesis, into the cell [18]. System XC− consists of a light-chain subunit (SLC7A11/xCT) and a heavy-chain subunit (SLC3A2). SLC7A11 exhibits transporter activity highly specific for glutamate and cysteine and thus plays an important role in providing cysteine for the biosynthesis of GSH. GSH is vital for glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), which protects cells against ferroptosis by converting toxic lipid hydroperoxides into nontoxic lipid alcohol [19]. Emerging strategies targeting ferroptosis have been developed to treat organ and tissue injury [20–22]. Furthermore, it is reported that MSC-Exo alleviates oxidative stress-induced dysfunction in mouse livers in vivo [23].

Hence, in this study, we investigated the role of ferroptosis in MSC-based treatment for ALI in vitro and in vivo. Our results showed that SLC7A11 was significantly downregulated in the ALI mouse model, and its down-regulation promoted CCl4-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis. MSC transplantation and MSC-Exo treatment largely abolished ferroptosis and protected the liver from injury. Moreover, MSC-Exo-mediated recovery of SLC7A11 protein was accompanied by the increase of CD44 and OTUB1 in ALI mouse livers. The stability of SLC7A11 was closely related to OTUB1-mediated deubiquitination. Finally, our studies indicated that MSC-Exo suppressed hepatocyte’s ferroptosis to mediate liver repair in ALI mice by maintaining SLC7A11 function.

Results

Ferroptosis drove CCl4-induced mouse models of ALI

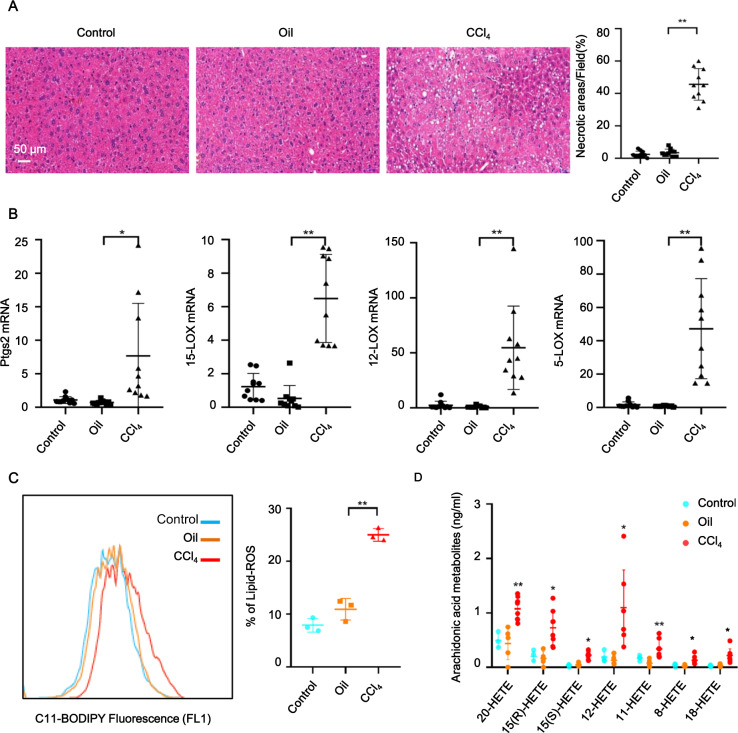

As shown in Fig. 1A, compared with control (PBS) and oil-treated groups (left and middle), typical histopathological changes of ALI, such as diffuse hepatic necrosis, were observed microscopically in the liver tissues from CCl4-treated groups. To investigate the contribution of ferroptotic cell death in CCl4-induced ALI, we performed real-time PCR analysis of putative molecular markers of ferroptosis and found that CCl4 treatment robustly induced increased mRNA levels of liver prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2), 15-LOX, 12-LOX, and 5-LOX (Fig. 1B). Next, we quantified lipid peroxidation in living liver cells by flow cytometry using the C11-BODIPY581/591 fluorescent probe, a canonical index of ferroptosis. Compared to PBS and oil treatments, the lipid-ROS levels in mouse livers were significantly elevated after CCl4 treatment (Fig. 1C). The release of an oxidized lipid mediator is a reported characteristic of ferroptosis [24]. Membranes with arachidonic acid enrichment may facilitate ferroptosis by releasing arachidonic acid metabolites (hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid) during cell death. Interestingly, the levels of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 15(R)-HETE, 15(S)-HETE, 12-HETE, 11-HETE, 8-HETE, and 18-HETE were increased in the livers from CCl4-treated mice (Fig. 1D). These findings suggested that ferroptosis is a crucial driver of CCl4-induced liver injury in mice.

Fig. 1. Ferroptosis occurred in livers of ALI mouse models.

A Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining showed that administration of CCl4 induced ALI in mice. B Ptgs2, 15-LOX, 12-LOX, and 5-LOX mRNA levels were measured in livers of 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice treated for 6 h with or without CCl4. mRNA levels were normalized to that of GAPDH and were expressed relative to the mean value in the PBS-treated mice. C Lipid peroxidation was measured using C11-BODIPY581/591 staining. D Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) analysis of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 15(R)-HETE, 15(S)-HETE, 12-HETE, 11-HETE, 8-HETE, and 18-HETE were performed in liver tissues. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001 indicated a significant difference between groups.

MSC transplantation alleviated CCl4-induced ferroptosis in ALI

We have previously reported that MSC treatment dramatically alleviated CCl4-induced ALI due to its immunomodulatory function [7]. Given that MSCs also play important roles in reducing oxidative stress [25], and oxidative stress-induced excessive accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides ultimately results in ferroptosis, we hypothesized that MSCs might exert a protective effect against ferroptosis by facilitating lipid-ROS scavenging in CCl4-induced ALI. Histopathological staining indicated that hepatic necrosis was drastically mitigated following administration of MSCs and ferrostatin-1(Fer-1, a ferroptosis inhibitor), demonstrating the therapeutic effect of MSCs against CCl4-induced ferroptosis in ALI (Fig. 2A). We observed significant decreases in mRNA levels of classic biomarkers of ferroptosis, including Ptgs2, 15-LOX, 12-LOX, and 5-LOX in MSC and Fer-1 groups (Fig. 2B). MSC treatment also potently reduced the accumulation of CCl4-induced lipid hydroperoxides in the liver (Fig. 2C). Notably, MSCs exhibited comparable therapeutic efficacy to ferrostatin-1, as evidenced by the similar trends in downregulating mRNA levels of liver Ptgs2 and LOXs, and lipid peroxidation. It is worth noting that LOXs (particularly 15-LOX) have been reported as essential regulators of ferroptotic cell death as they contribute to the cellular pool of lipid hydroperoxides [26, 27]. Moreover, the increased levels of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 15(R)-HETE, 15(S)-HETE, 12-HETE, 11-HETE, 8-HETE, and 18-HETE induced by CCl4 were abrogated by MSC and Fer-1 treatment (Fig. 2D). These results suggested that the potential ability of MSCs to down-regulate peroxidation resulted in lipid-ROS reduction and inhibited the progression of ferroptosis.

Fig. 2. MSC treatment prevented CCl4-induced ferroptosis in ALI.

A HE staining showed that MSC and ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) treatment alleviated CCl4-induced ALI. B Ptgs2, 15-LOX, 12-LOX, and 5-LOX mRNA levels were measured in mouse livers of CCl4, MSC, and Fer-1 groups. mRNA levels were normalized to that of GAPDH. C Lipid peroxidation was measured by C11-BODIPY581/591 staining. Lipid peroxidation of hepatocytes in the liver was significantly increased in the CCl4 group but significantly reduced in MSC and Fer-1 groups. D UPLC-MS/MS detection showed increased levels of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 15(R)-HETE, 15(S)-HETE, 12-HETE, 11-HETE, 8-HETE, and 18-HETE in mouse livers of the CCl4 group, and these effects were abrogated by MSC and Fer-1 treatment. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001 indicated a significant difference between groups.

SLC7A11 protein level was reduced in CCl4-induced ALI but increased following MSC treatment in vivo and in vitro

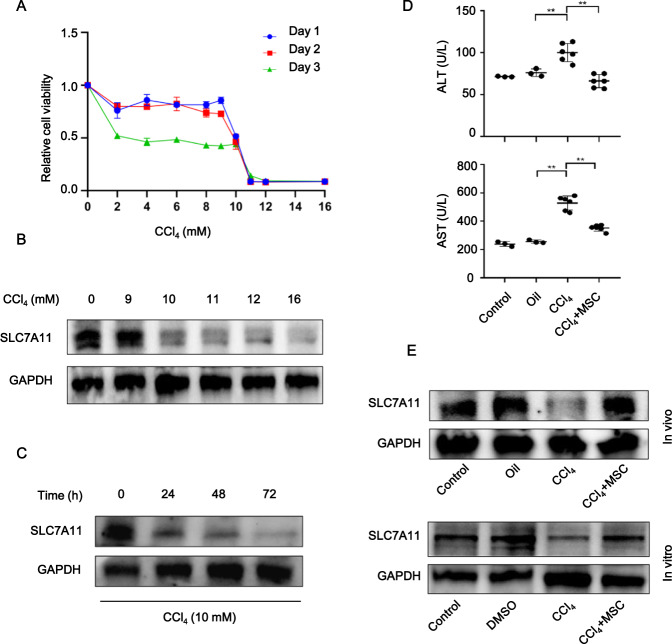

Next, we established an in vitro acute hepatocyte injury model to further investigate the therapeutic mechanism of MSCs in ALI treatment. On days 1, 2, and 3, a dramatic decrease in cell viability was detected using the Cell Counting Kit-8 when CCl4 concentration was increased to 10 mM (Fig. 3A). To excavate the role of SLC7A11 protein in the CCl4-induced acute hepatocyte injury model, we performed WB analysis to assess the dose- and time-dependent effects of CCl4 treatment on SLC7A11 expression. SLC7A11 protein level was significantly downregulated at the CCl4 concentration of 10 mM (Fig. 3B and Fig. S1A). Furthermore, the decreased SLC7A11 protein levels were detected at 24, 48, and 72 h after CCl4 treatment (10 mM) (Fig. 3C and Fig. S1B).

Fig. 3. SLC7A11 protein level was downregulated in CCl4-induced ALI and upregulated following MSC treatment in vivo and in vitro.

A Cell viability was measured on days 1, 2, and 3, after hepatocytes were treated with 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 16 mM CCl4. B WB analysis was performed to measure the SLC7A11 protein level in mouse primary hepatocytes treated with 0, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 16 mM CCl4 for 48 h. C or with 10 mM CCl4 for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. D Coculture of primary hepatocytes with MSCs significantly reduced AST and ALT induced by CCl4. E MSC treatment significantly reduced the downregulated SLC7A11 protein level induced by CCl4 in vivo and in vitro. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001 indicated a significant difference between groups.

As previous studies concluded that only a small percentage of injected MSCs reached their targets, we speculated that some active substances derived from MSCs might participate more profoundly in alleviating ALI. Recent studies have shown that MSCs produce exosomes, which can ameliorate tissue injury via the delivery of their DNA, miRNA, and protein contents [28–30]. Given this, we hypothesized that these extracellular vesicles were actively facilitated the protective effects of MSCs against ferroptosis. Subsequent to the above primary hepatocyte model, a coculture system, where MSCs were physically separated from damaged hepatocytes by transwell chambers, was exploited to investigate whether the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs can be achieved. As shown in Fig. 3D, AST and ALT levels were significantly increased in the CCl4 group but then dramatically reduced after MSCs coculture. Next, to ascertain whether coculture with MSCs can also rescue the CCl4-induced decrease in SLC7A11 protein level in primary hepatocytes, WB analysis was performed. Interestingly, similar to the in vivo findings, SLC7A11 protein level was reduced in the CCl4 group compared with the PBS group but was restored by MSCs coculture (Fig. 3E and Fig. S1C, D). These results suggested that something like the exosome derived from MSCs mediated the regulation of SLC7A11 protein levels to facilitate the protective effect of MSCs against ferroptosis.

MSC-Exo inhibited ferroptosis in CCl4-induced ALI in vitro

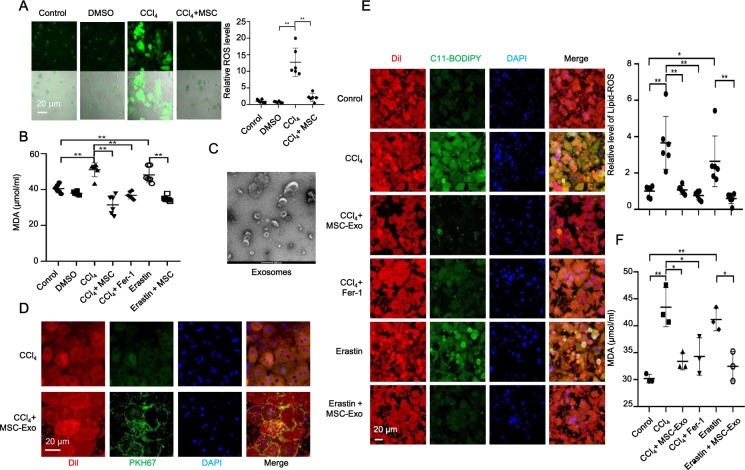

To further examine the role of MSCs in ALI, we quantified the levels of ROS and MDA. As shown in Fig. 4A, MSCs coculture reduced ROS accumulation induced by CCl4 in hepatocytes. In addition, CCl4 induced a dramatic increase of MDA, similar to erastin (a ferroptosis inducer), while coculture with MSCs, similar to Fer-1 treatment, downregulated MDA level both in CCl4 and Erastin group in hepatocytes (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. MSC-Exo mediated the effect of MSCs against CCl4-induced ferroptosis in vitro.

A Relative ROS levels were measured by H2DCFDA staining in primary hepatocytes treated with control (PBS), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), or 10 mM CCl4 for 48 h with or without MSCs coculture. B The increased MDA level induced by CCl4 was downregulated by MSCs coculture and Fer-1 treatment in primary hepatocytes. The increased MDA level induced by erastin was also downregulated by MSCs coculture in primary hepatocytes. C Refrigerated transmission electron microscopy was used to assess exosomes isolated from MSCs. D Exosomes collected from MSC-conditioned medium were labeled with PKH67 and incubated with CCl4-induced acute injured hepatocytes for 24 h. The cell membrane was stained with Dil. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. PKH67 lipid dye was detected in damaged hepatocytes treated with PKH67-labeled exosomes in the CCl4 group. E Isolated hepatocytes were incubated with C11-BODIPY581/791 and then analyzed by using laser confocal focus. Cell membrane was stained with Dil. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. C11-BODIPY581/591 staining showed a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in hepatocytes following CCl4 and erastin treatment, while MSC-Exo and Fer-1 downregulated the increased lipid peroxidation induced by CCl4 and erastin. F The increased MDA level induced by CCl4 and erastin were downregulated by MSC-Exo and Fer-1 treatments in primary hepatocytes. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001 indicated a significant difference between groups.

Next, we extracted and identified exosomes from an MSC-conditioned medium. We used refrigerated transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 4C) and WB analysis to characterize vesicles recovered from the MSC-conditioned medium by differential ultracentrifugation and identified 30–100 nm vesicles that were morphologically similar to exosomes, which expressed the exosomal markers of CD63 and CD81 (Figs. S2A, S3A). To determine whether hepatocytes can internalize MSC-Exo, exosomes were manually labeled with green lipophilic fluorescent dye PKH67 (PKH67GL; Sigma-Aldrich), and were subsequently cocultured with CCl4-induced injury hepatocytes. The hepatocytes exhibited high uptake efficiency, as indicated by the strong green fluorescent signal (Fig. 4D). Next, we measured the lipid peroxidation in CCl4-treated primary hepatocytes with or without MSC-Exo treatment. Similar to erastin, CCl4 induced significant upregulation of lipid-ROS and MDA levels, whereas MSC-Exo or Fer-1 treatment comparably decreased the level of lipid-ROS (Fig. 4E) and MDA (Fig. 4F). These data suggested that MSC-Exo inhibited ferroptosis in CCl4-induced ALI in vitro.

MSC-Exo inhibited ferroptosis in CCl4-induced ALI in vivo

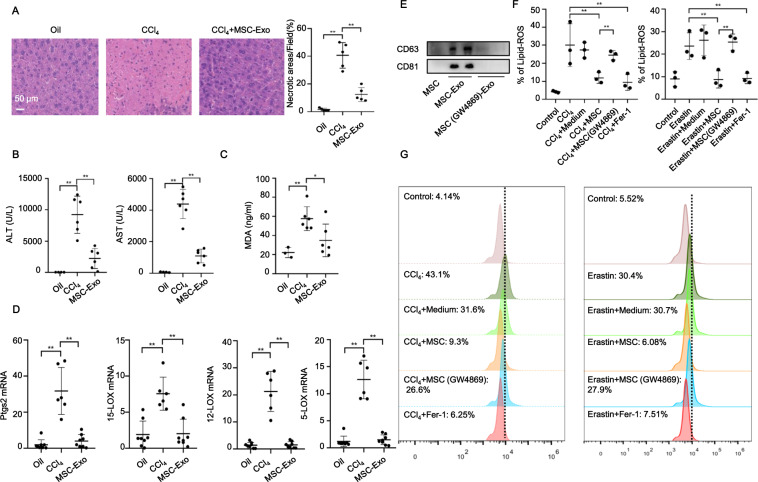

Inspired by the in vitro potency of MSC-Exo, we next investigated the effects of MSC-Exo in CCl4-induced ferroptosis in vivo. Interestingly, consistent with the protective effects of MSCs in vivo, MSC-Exo also ameliorated hepatic necrosis and downregulated the aberrant ALT/AST in CCl4-induced ALI (Fig. 5A, B). In addition, as evidenced by MDA quantification and real-time PCR analysis of ferroptosis-related markers, MSC-Exo treatment significantly downregulated MDA levels and mRNA levels of liver Ptgs2, 15-LOX, 12-LOX, and 5-LOX (Fig. 5C, D). These findings suggested that MSC-Exo also inhibited ferroptosis in CCl4-induced ALI in vivo.

Fig. 5. MSC-Exo mediated the effect of MSCs against CCl4-induced ferroptosis in vivo.

A HE staining showed that MSC-Exo treatment alleviated CCl4-induced ALI. B MSC-Exo dramatically reversed the increased serum levels of ALT and AST induced by CCl4. C UPLC-MS/MS detection indicated significant upregulation of the serum MDA level induced by CCl4, which was downregulated following MSC-Exo treatment. D MSC-Exo treatment significantly reversed the increased mRNA levels of Ptgs2, 15-LOX, 12-LOX, and 5-LOX induced by CCl4 in the liver. E WB analysis of CD63 and CD81 in exosomes extracted from MSC-conditioned medium and GW4869 pretreated MSC-conditioned medium. F Lipid peroxidation was measured using C11-BODIPY581/591 staining in L-02 cells treated with CCl4, CCl4 + Medium, CCl4 + MSC, CCl4 + MSC (pretreated with GW4869), and CCl4 + Fer-1 (left panel). After replacing CCl4 with erastin, the above experiment was repeated three times (right panel). G Representative histograms of C11-BODIPY581/591 staining. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001 indicated a significant difference between groups.

To confirm the anti-ferroptotic effect of MSC-Exo, we used GW4869 to inhibit the release of exosomes in MSCs. WB analysis revealed that the secretion of exosomes was significantly inhibited by GW4869 in MSCs (Fig. 5E and Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 5F, G, MSC pretreated with GW4869 (10 µM) showed limited potency in downregulating lipid-ROS levels. What’s more, in vivo study also demonstrated that MSC pretreated with GW4869 showed limited potency in downregulating lipid-ROS levels as evidenced by 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE; another marker of lipid peroxidation) detection (Fig. S5).

MSC-Exo protected against ferroptosis via stabilization of SLC7A11 in ALI

Next, we investigated how MSC-Exo realized its protective potency against CCl4-induced ferroptosis. Here, more focus was paid to the dynamic regulation of SLC7A11 protein. Accumulating evidence indicated that SLC7A11 was modulated by CD44 [18, 31], a cell surface marker of MSCs [7] and a critical molecule for MSCs recruitment to CCl4-induced ALI livers by the firm adhesion between MSCs and injured liver tissues [32]. Desirably, we detected CD44 protein expression in MSC-Exo (Figs. S2A, S3A). In the above study, compared to healthy mice in the PBS group, a reduced SLC7A11 protein level was detected among CCl4-induced ALI mice but can be restored after MSC treatment. Therefore, we hypothesized that the SLC7A11 level was functionally related to the anti-ferroptotic effects of MSC-Exo treatment.

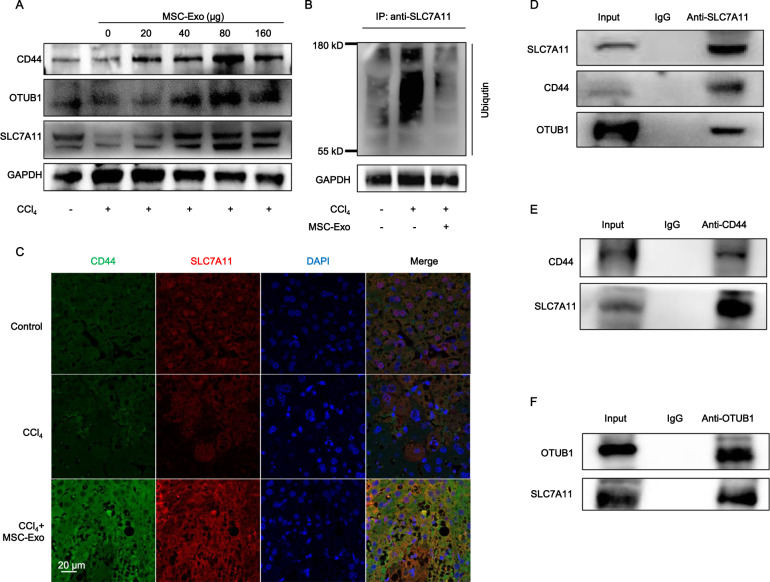

As shown in Fig. 6A (Fig. S6A), SLC7A11 protein levels in acute injured hepatocytes treated with 0, 20, 40, 80, and 160 µg MSC-Exo were measured by WB analysis. Interestingly, MSC-Exo-induced recovery of SLC7A11 protein was accompanied by increasing of CD44 and OTUB1. What’s more, MSC-Exo treatment also induced recovery of SLC7A11 and CD44 in vivo (Figs. S2B, S3B). OTUB1 is an ovarian tumor deubiquitinase family member with reported functions to regulate SLC7A11 stability via direct protein interaction [33]. Accordingly, we found that CCl4 administration increased the ubiquitination of SLC7A11, while MSC-Exo treatment downregulated the ubiquitination of SLC7A11 (Fig. 6B and Fig. S6B). The above data suggested that CCl4-induced ubiquitination abolished the stabilization of SLC7A11, leading to a downregulated level of SLC7A11 in ALI. However, MSC-Exo treatment restored the stabilization of SLC7A11 by inhibiting its ubiquitination, resulting in upregulation of SLC7A11 in ALI.

Fig. 6. MSC-Exo protected against ferroptosis via the stabilization of SLC7A11 in ALI.

A CD44, OTUB1, and SLC7A11 protein levels in CCl4-induced acute injured hepatocytes treated with 0, 20, 40, 80, and 160 µg MSC-Exo were detected by WB analysis. B CCl4-induced ALI increased ubiquitination of SLC7A11 in hepatocytes, and this effect was downregulated following MSC-Exo treatment. C Immunofluorescence assay was used to detect the protein levels of CD44 and SLC7A11 in liver tissues. D WB analysis of CD44 and OTUB1 after co-immunoprecipitation of anti-SLC7A11 from liver tissue in CCl4 group treated with MSC-Exo. One percent of the sample was loaded as input. E WB analysis of SLC7A11 after co-immunoprecipitation of anti-CD44 from liver tissue in CCl4 group treated with MSC-Exo. One percent of the sample was loaded as input. F WB analysis of SLC7A11 after co-immunoprecipitation of anti-OTUB1 from liver tissue in CCl4 group treated with MSC-Exo. One percent of the sample was loaded as input. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.001 indicated a significant difference between groups.

To determine the mechanism by which MSC-Exo exerted protective effects against ferroptosis, we performed immunofluorescence and co-immunoprecipitation analyses. Immunofluorescence analysis suggested that CD44 and SLC7A11 were co-expressed and increased in ALI after MSC-Exo treatment compared with CCl4 and PBS groups (Fig. 6C). Next, to measure the interaction under physiological conditions, we performed co-immunoprecipitation analysis targeting endogenous proteins expressed in liver tissues of ALI after MSC-Exo treatment. As shown in Fig. 6D (Fig. S6C), the endogenous CD44 and OTUB1 proteins were co-precipitated by a SLC7A11-specific antibody, while endogenous SLC7A11 was co-precipitated by a CD44-specific and OTUB1-specific antibody, respectively (Fig. 6E, F and Fig. S6D, E). Thus, we further speculated that MSC-Exo treatment promotes the increase of CD44 and OTUB1 proteins and stabilizes SLC7A11 by directly interacting with and reducing its ubiquitination in CCl4-induced ALI.

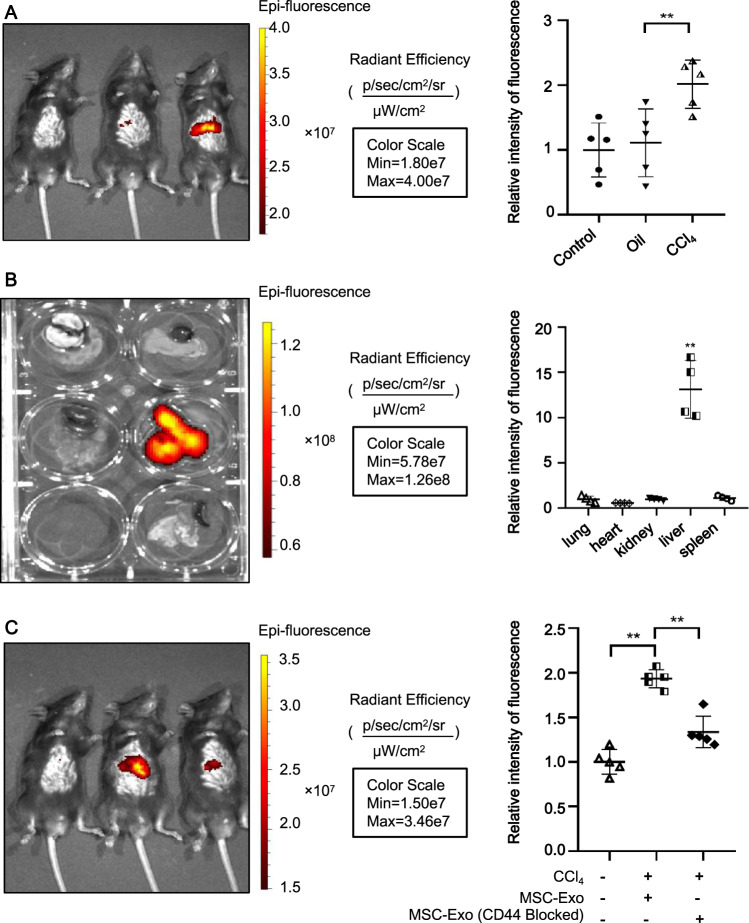

MSC-Exo in the circulation localized more readily in the injured liver

Next, we assessed whether MSC-Exo was preferentially accumulated within injured livers. For this purpose, MSC-Exo was first isolated from an MSC-conditioned medium and then labeled with lipophilic carbocyanine DiR. After intravenous injection via tail vein to ALI mice, the bio-distribution of DiR-labeled MSC-Exo was visualized by an IVIS imaging system. From in vivo fluorescent imaging, the accumulation of DiR-labeled MSC-Exo was detected within the injured and healthy livers 6 h postinjection. However, stronger fluorescence was observed in livers from ALI mice compared to those from PBS or oil groups (Fig. 7A), indicating that circulating MSC-Exo was more likely to aggregate in damaged tissue sites. We also evaluated the fluorescence intensity within major organs including lungs, hearts, kidneys, livers, and spleens of ALI mice treated with DiR-labeled MSC-Exo. As shown in Fig. 7B, significantly higher fluorescent signals were observed in the liver compared with other organs, suggesting that MSC-Exo in circulation localized more readily in the livers in ALI mice. However, neutralizing antibodies against CD44 reduced MSC-Exo targeting to the diseased liver (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7C). These results indicated that the affinity of MSC-Exo to injured liver tissues was assisted by the binding function of CD44.

Fig. 7. MSC-Exo in the circulation was more readily localized in the damaged liver.

A Whole-body fluorescence imaging of C57BL/6 male mice treated with 8 mg/kg labeled MSC-Exo. Images were taken 6 h after tail vein injection. B Quantitative fluorescent imaging of lung, heart, kidney, liver, and spleen from recipient mice receiving labeled MSC-Exo. C Neutralizing antibodies against CD44 reduced hepatic engraftment of MSC-Exo in ALI murine livers. Images were taken at 6 h. Data were the mean ± SD fluorescence; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001; n = 5. Individual images were presented.

Discussion

Ferroptosis is a newly recognized non-apoptotic form of regulated cell death characterized by an overwhelming accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides that contributes to a wide range of pathologies, including cancer, neurodegeneration, and tissue injury [16, 34, 35]. Accumulating evidence suggested that patients with liver diseases were likely to suffer from ferroptosis-regulated cell death [34, 36]. Recently, it was reported that ferroptosis also participated in liver fibrosis [37].

In this study, aside from the expansion of liver necrotic areas, lipid hydroperoxides were also dramatically upregulated within ALI livers, suggesting excessive accumulation of lipid-ROS. Furthermore, we observed increased expression of ferroptosis-relevant genes after CCl4 treatment such as Ptgs2 and LOXs. Ptgs2, also known as cyclooxygenase-2, was induced in cells undergoing ferroptosis [19]. Thus, these results suggested that ferroptosis-mediated cell death occurred in CCl4-induced ALI. In addition, as ferrostatin-1 and MSC treatment exhibited similar therapeutic efficacy in downregulating lipid-ROS accumulation and ferroptosis-relevant gene expression in the ALI mouse model, our observations shed an intriguing light on the protective role of MSCs against ferroptosis. Further investigations should be conducted to fully elucidate this anti-ferroptotic mechanism of MSCs.

Recently, increasing evidence has shown that most of the MSC-mediated beneficial effects can be attributed to the functions of released exosomes. For instance, exosomes from human umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs can protect livers against ALI via intercellular communication [23]. Therefore, we further evaluated the hepatoprotective role of MSC-Exo. Inspiringly, our study revealed that MSC-Exo treatment resulted in equal alleviation as MSCs both in vivo and in vitro. To fully explore the underlying mechanism, we tested the effect of MSC-Exo on liver antioxidant systems and found that MSC-Exo significantly attenuated CCl4-provoked lipid peroxidation, as manifested by the levels of MDA and lipid ROS in liver tissues and hepatocytes. In addition, MSC-Exo also abolished other ferroptosis markers raised by CCl4 treatment, including decreased expressions of SLC7A11 and increased expressions of Ptgs2 and LOXs. Thus, we concluded that MSC-Exo protected against CCl4-induced liver injury through inhibiting hepatocyte ferroptosis.

System XC−-mediated antioxidant defense can effectively protect cells and tissues against ferroptosis [38]. SLC7A11, a multi-pass transmembrane protein, mediates the cystine/glutamate antiporter activity in the system XC−. Once transported into the cell, cystine is rapidly converted to cysteine, which is the rate-limiting precursor of GSH. Inhibition of SLC7A11 has been reported to increase ferroptosis sensitivity [39]. Emerging evidence suggested that upregulation of SLC7A11 promoted cell growth by suppressing ferroptosis. Here, we showed that treatment with CCl4 reduced the protein level of SLC7A11 in mouse liver and primary hepatocytes. However, MSC-Exo efficiently restituted the aberrant level of ALT/AST and restored the SLC7A11 protein level in ALI mice. Thus, we concluded that MSC-Exo protected against CCl4-induced ALI through inhibiting hepatocyte ferroptosis via restoring the SLC7A11 protein level. Additionally, the exosome-induced recovery of SLC7A11 protein was accompanied by upregulations of CD44 and OTUB1. CD44 is a major adhesion molecule in the extracellular matrix and is involved in a variety of physiological processes, including stem cell homing, wound healing, and cell migration [40, 41]. Several studies have found that CD44 stabilizes SLC7A11 expression at the plasma membrane, with the System xc− then mediating cystine uptake and promoting GSH synthesis [18]. And OTUB1, a deubiquitinase, has the function to regulate SLC7A11 stability via direct protein interaction. These data indicated that MSC-Exo might alleviate ferroptosis via the CD44 and OTUB1-mediated stabilization of SLC7A11. More interestingly, MSC-Exo in the circulation was preferentially localized in damaged livers. Since the same amount of MSC-Exo was injected, the observed difference in localization may be driven by factors intrinsic to MSC-Exo. The target specificity of exosomes is thought to be mediated by adhesion proteins on the surface of the vesicles [42]. Interestingly, we observed a high expression of CD44 both in MSCs and MSC-Exo. What’s more, it has been demonstrated that MSCs can adhere to liver tissue in diseased conditions. And these adhesive events are largely regulated by CD44 [32]. In this study, more fluorescence was detected in the damaged liver, suggesting that MSC-Exo had the same aggregation function as MSCs. In addition, liver localization of MSC-Exo was blocked by preincubation with CD44 blocking antibody. Thus, we suggest that CD44 recruit MSC-Exo to the injured liver and enhance liver recovery. But the underlying mechanism by which MSC-Exo restored the expression of CD44 in damaged hepatocytes remains further study. We prefer to speculate that hepatic uptake of CD44 expressing MSC-Exo promoted the accumulation of CD44 in hepatocytes. However, it is not excluded that other components in exosomes, such as miRNA, lncRNA, or other protein components, play a role in regulating CD44 protein levels. Taken together, this study has vital implications in illustrating how MSC-Exo-mediated anti-ferroptotic effects are achieved in ALI. However, the specific mechanism remains to be further studied.

Materials and methods

Preparation of MSCs and MSC-Exo

MSCs were obtained from compact bones of 1-week-old C57BL/6 male mice [7, 43]. MSCs from passages 3–5 were used in the experiments. Detailed information was shown in the supplementary materials.

MSCs were cultured in an exosome-free medium (with or without 10 µM GW4869, HY-19363; MedChemExpress, an exosome inhibitor), and exosomes were isolated and purified by ultracentrifugation. Briefly, MSC-conditioned medium was collected after 48 h of culture and centrifuged at 2000×g for 20 min to remove debris and cells. The supernatant was collected and transferred to a new sterile tube and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.22-µm-pore sterile filter, followed by ultracentrifugation at 110,000 × g for 70 min at 4 °C to obtain exosome pellets, which were resuspended in PBS and stored at −80 °C. We used the BCA protein assay kit (UD283191; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to determine the protein content of the concentrated exosomes. Exosomes were identified by Western blot (WB) analysis of the marker proteins CD63 and CD81. The morphology of exosomes was observed using a 120 kV refrigerated transmission electron microscope (Tecnai Spirit Bio-TWIN, FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA). The MSC-Exo concentration used in vivo was 8 mg/kg body weight.

Mouse models of ALI

ALI induction was performed in 6–8-week-old age-matched C57BL/6 J male mice (n = 10–12 per group) by intraperitoneal injection of 3 mL/kg CCl4 (Sigma-Aldrich Trading Co., Shanghai, China) in coconut oil (v/v, 50%, Sigma-Aldrich). Control and negative control mice were injected with PBS and coconut oil, respectively. At 6 h after injection of CCl4, mice were divided into three groups: CCl4 group, injected with 100 µL PBS (supplemented with 2% mouse serum) through a tail vein; CCl4 + MSC group, injected with 5 × 105 MSCs suspended in 100 µL PBS (supplemented with 2% mouse serum) through a tail vein; CCl4 + Fer-1 group, intraperitoneally injected with ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1, a ferroptosis inhibitor, 2.5 μmol/kg body weight). Erastin, intraperitoneal injection of erastin (a ferroptosis inducer, 30 mg/kg body weight) twice every other day, and then the mice were divided into two groups (n = 10–12 per group): Erastin group, injected with 100 µL PBS (supplemented with 2% mouse serum) through a tail vein; Erastin + MSC group, injected with 5 × 105 MSCs suspended in 100 µL PBS (supplemented with 2% mouse serum) through the tail vein. The mice were sacrificed 48 h after MSCs injection, and serum and liver tissues were collected for subsequent analysis. The individuals caring for the animals and conducting the experiments were blinded to the allocation sequence, blinded to group allocation. Randomization was used to determine the allocation of animals to the experiments.

Isolation and incubation of primary hepatocytes

The same ALI mouse models were established. Primary hepatocytes were collected according to the rapid two-step method using collagenase perfusion. We cultured the primary hepatocytes in William’s E Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Biosciences, Waltham, MA, USA), 10 mg/mL streptomycin, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 1% ITS liquid medium supplement (Sigma-Aldrich, I3146), and 40 ng/mL dexamethasone. Human normal hepatocyte (L-02) cells (purchased from KCB) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco Biosciences, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% FBS.

Lipid peroxidation, ROS, MDA, and cell viability measurements

Lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) were detected by fluorescent probe C11-BODIPY581/591 (D3861; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (D6883; Sigma-Aldrich) staining [15]. We used a kit (S0131S; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) to detect the hepatic malondialdehyde (MDA) content and the Cell Counting Kit-8 viability assay (Sigma-Aldrich) to determine cell viability.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from liver tissue using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried out using the PrimeScript RT kit (Takara, Beijing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on the ABI QuantStudio-5 (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green Supermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). Relative gene expression in real-time PCR was calculated as follows. First, we obtained the ΔCT value by subtracting the average CT value of the reference gene from the average CT value of the target gene. Then, the average ΔCT value in the control group was calculated and the corresponding ΔΔCT values were obtained by subtracting this average from the average value of each ΔCT value in each group. Next, the 2-ΔΔCT value was calculated. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and melting curve analysis was performed to monitor the specificity.

Western blot analysis

The following antibodies were used in WB analysis: anti-ubiquitin (ab134953; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), SLC7A11 (D2M7A; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-OTUB1 (ab175200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-CD44 (ab189524; Abcam), anti-SLC7A11 (ab175186; Abcam), anti-CD44 (ab119348; Abcam), rabbit monoclonal [EPR5702] to CD63 (ab134045; Abcam), rabbit monoclonal [EPR4244] to CD81 (ab109201; Abcam), GAPDH Monoclonal antibody (60004-1-Ig; Proteintech), Beta Tubulin Polyclonal antibody (10094-1-AP; Proteintech) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (ab6721; Abcam).

Visualization of lipid peroxidation

Hepatocytes harvested from mice were resuspended in 500 μL PBS containing C11-BODIPY581/591 (2.5 μM) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a tissue culture incubator. The cell membrane was stained with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (Dil, D3911; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), a lipophilic membrane dye. The nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, D21490; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Finally, cells were washed twice with PBS, strained through a 70 μM cell strainer, and analyzed by laser confocal microscopy.

Immunofluorescence staining and co-immunoprecipitation

We used slides containing mouse liver tissues or primary hepatocytes. The slides were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The following day, after incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody, the nuclei were stained with DAPI before observing by confocal laser microscopy. Co-immunoprecipitation analysis was carried out using the Pierce Co-Immunoprecipitation Kit (26149; Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MSC-Exo labeling and tracking in mice

The details of MSC-Exo labeling and tracking procedures were provided in the supplementary materials.

Statistical analysis

The results were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed by GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The student’s t-test was performed to compare the values between the two groups. We performed one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to compare data obtained from multiple groups. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

The procedures for isolation and culture of mouse MSCs, WB analysis, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids detection method by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) and preparation of CCl4-induced hepatocytes injury were described in the supplementary materials.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jinlin Cheng of the Department of Pathology at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine for her professional review of histopathology.

Author contributions

FL, LL, and HC contributed to the research conception and design. FL, WC, JHZ, JQZ, and QY performed the experiments. BF, XF, XS, QP, and JY performed data analysis. FL and HC drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants for the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81971756); and Stem Cell and Translational Research from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFA0113003).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

All animal experimental procedures were conducted according to a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University.

Footnotes

Edited by Dr. Yufang Shi

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41419-022-04708-w.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Shao M, Wu Y, Yan C, Jiang S, Liu J, et al. Role for the endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1alpha in liver regenerative responses. J Hepatol. 2015;62:590–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samra YA, Hamed MF, El-Sheakh AR. Hepatoprotective effect of allicin against acetaminophen-induced liver injury: Role of inflammasome pathway, apoptosis, and liver regeneration. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2020;34:e22470. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CA, Sinha S, Fitzpatrick E, Dhawan A. Hepatocyte transplantation and advancements in alternative cell sources for liver-based regenerative medicine. J Mol Med. 2018;96:469–81. doi: 10.1007/s00109-018-1638-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhakuni GS, Bedi O, Bariwal J, Deshmukh R, Kumar P. Animal models of hepatotoxicity. Inflamm Res. 2016;65:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s00011-015-0883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao F, Chiu SM, Motan DA, Zhang Z, Chen L, Ji HL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2062. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Feng B, Xu Y, Zhu J, Feng X, Chen W, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells in chemical-induced liver injury: a high-dimensional analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:262. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1379-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao J, Dennis JE, Muzic RF, Lundberg M, Caplan AI. The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000047856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borgovan T, Crawford L, Nwizu C, Quesenberry P. Stem cells and extracellular vesicles: biological regulators of physiology and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;317:C155–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00017.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie L, Chen Z, Liu M, Huang W, Zou F, Ma X, et al. MSC-derived exosomes protect vertebral endplate chondrocytes against apoptosis and calcification via the miR-31-5p/ATF6 Axis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;22:601–14. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T, Jian Z, Baskys A, Yang J, Li J, Guo H, et al. MSC-derived exosomes protect against oxidative stress-induced skin injury via adaptive regulation of the NRF2 defense system. Biomaterials. 2020;257:120264. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macias-Rodriguez RU, Inzaugarat ME, Ruiz-Margain A, Nelson LJ, Trautwein C & Cubero FJ. Reclassifying hepatic cell death during liver damage: ferroptosis-a novel form of non-apoptotic cell death? Int. J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Yamada N, Karasawa T, Kimura H, Watanabe S, Komada T, Kamata R, et al. Ferroptosis driven by radical oxidation of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids mediates acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:144. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, He H, Wang J, Guo X, Lin H, Chen H, et al. Oxidative stress-dependent frataxin inhibition mediated alcoholic hepatocytotoxicity through ferroptosis. Toxicology. 2020;445:152584. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, An P, Xie E, Wu Q, Fang X, Gao H, et al. Characterization of ferroptosis in murine models of hemochromatosis. Hepatology. 2017;66:449–65. doi: 10.1002/hep.29117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng X, Deng J, Liu F, Guo T, Liu M, Dai P, et al. Triggered all-active metal organic framework: ferroptosis machinery contributes to the apoptotic photodynamic antitumor therapy. Nano Lett. 2019;19:7866–76. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishimoto T, Nagano O, Yae T, Tamada M, Motohara T, Oshima H, et al. CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(-) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny EM, Fidan E, Yang Q, Anthonymuthu TS, New LA, Meyer EA, et al. Ferroptosis contributes to neuronal death and functional outcome after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:410–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R. Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;59:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Feng D, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Sun R, Tian D, et al. Ischemia-induced ACSL4 activation contributes to ferroptosis-mediated tissue injury in intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:2284–99. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0299-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Y, Jiang W, Tan Y, Zou S, Zhang H, Mao F, et al. hucMSC exosome-derived GPX1 is required for the recovery of hepatic oxidant injury. Mol Ther. 2017;25:465–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:1180–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Michaeloudes C, Zhang Y, Wiegman CH, Adcock IM, Lian Q, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in the airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1634–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M, Shchepinov MS, Stockwell BR. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E4966–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603244113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah R, Shchepinov MS, Pratt DA. Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4:387–96. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao J, Wang B, Tang T, Lv L, Ding Z, Li Z, et al. Three-dimensional culture of MSCs produces exosomes with improved yield and enhanced therapeutic efficacy for cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:206. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01719-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Zhang Y, Mu J, Chen J, Zhang C, Cao H, et al. Transplantation of human mesenchymal stem-cell-derived exosomes immobilized in an adhesive hydrogel for effective treatment of spinal cord injury. Nano Lett. 2020;20:4298–305. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Li J, Ma B, Li N, Wang S, Sun Z, et al. MSC-derived exosomes promote recovery from traumatic brain injury via microglia/macrophages in rat. Aging. 2020;12:18274–96. doi: 10.18632/aging.103692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ju HQ, Lu YX, Chen DL, Tian T, Mo HY, Wei XL, et al. Redox regulation of stem-like cells though the CD44v-xCT axis in colorectal cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Theranostics. 2016;6:1160–75. doi: 10.7150/thno.14848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldridge V, Garg A, Davies N, Bartlett DC, Youster J, Beard H, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells are recruited to injured liver in a beta1-integrin and CD44 dependent manner. Hepatology. 2012;56:1063–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.25716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T, Jiang L, Tavana O, Gu W. The deubiquitylase OTUB1 mediates ferroptosis via stabilization of SLC7A11. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1913–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Yao Z, Wang L, Ding H, Shao J, Chen A, et al. Activation of ferritinophagy is required for the RNA-binding protein ELAVL1/HuR to regulate ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Autophagy. 2018;14:2083–103. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1503146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hambright WS, Fonseca RS, Chen L, Na R, Ran Q. Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2017;12:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Du L, Qiao Y, Zhang X, Zheng W, Wu Q, et al. Ferroptosis is governed by differential regulation of transcription in liver cancer. Redox Biol. 2019;24:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Zhang Z, Li M, Wang F, Jia Y, Zhang F, et al. P53-dependent induction of ferroptosis is required for artemether to alleviate carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation. IUBMB Life. 2019;71:45–56. doi: 10.1002/iub.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koppula P, Zhuang L, Gan B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell 2021;12:599–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Wang Z, Ding Y, Wang X, Lu S, Wang C, He C, et al. Pseudolaric acid B triggers ferroptosis in glioma cells via activation of Nox4 and inhibition of xCT. Cancer Lett. 2018;428:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Govindaraju P, Todd L, Shetye S, Monslow J, Pure E. CD44-dependent inflammation, fibrogenesis, and collagenolysis regulates extracellular matrix remodeling and tensile strength during cutaneous wound healing. Matrix Biol. 2019;75-76:314–30. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khaldoyanidi S. Directing stem cell homing. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Li P, Zhu J, Lin F, Zhou J, Feng B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunomodulation of recruited mononuclear phagocytes during acute lung injury: a high-dimensional analysis study. Theranostics. 2021;11:2232–46. doi: 10.7150/thno.52514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.