Abstract

This article discusses the use of the Most Significant Change (MSC) technique in a mixed-methods evaluation of a pilot wellbeing programme for obstetrics and gynaecology doctors-in-training introduced at a large public hospital during Melbourne, Australia’s second coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown, which occurred from 7 July to 26 October 2020. The evaluation was conducted remotely using videoconferencing technology, to conform with pandemic restrictions. MSC complemented the program’s participatory principles and was chosen because it seeks to learn about participants’ perceptions of programme impacts by evaluating their stories of significant change. Stakeholders select one story exemplifying the most significant change resulting from the evaluated program. Inductive thematic analysis of all stories is combined with reasons for making the selection, to inform learnings (Dart & Davies, 2003; Tonkin et al., 2021). Nine stories of change were included in the selection. The most significant change was a more supportive workplace culture brought about by enabling basic needs to be met and breaking down hierarchical barriers. This was linked to five interconnected themes – connection, caring, communication, confidence and cooperation. The evaluation learnings are explored and reflections on remotely conducting MSC evaluation are shared.

Keywords: Most Significant Change technique, COVID-19 pandemic, workplace wellbeing programmes, pandemic kindness movement, doctors-in-training, Zoom, healthcare programme evaluation

Introduction

This article discusses learnings from the evaluation of a pilot wellbeing programme for obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) doctors-in-training (DiT) at a large public hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia – during the state’s second coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic lockdown, from 7 July to 26 October 2020. The Most Significant Change (MSC) technique was chosen as a qualitative evaluation method to learn about participants’ experience of change, to identify outcomes of most significance and to inform development and implementation of future programmes. Due to physical distancing requirements, the evaluation was conducted remotely using Zoom (San Jose, CA: Zoom Video Communications Inc) videoconferencing for interviews and meetings.

The programme and its evaluation are uniquely situated. Since January 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has dominated population health and wellbeing concerns across the world, with Melbourne, Australia being locked down longer than any city, totalling 262 days (Reuters, 2021). Against this backdrop, we explore several topics yet to emerge in the literature: the application of the MSC technique to evaluating a workplace wellbeing programme, learnings and key themes for consideration when developing similar programmes, and reflections on using remote communication technologies, such as Zoom, when using the MSC technique.

Background

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the stress levels of healthcare workers in acute hospital settings is well documented (Bridson et al., 2021; Heath et al., 2020; Kane, 2021; Shreffler et al., 2020). Prior to the pandemic, the wellbeing of Australian junior doctors was significantly lower than the general population (Soares & Chan, 2016). A 2008 national survey of 914 Australian DiT found 69% were at risk of burnout and 54% of compassion fatigue, despite self-reporting high levels of career satisfaction (Markwell & Wainer, 2009). In a 2021 survey of 12,000 physicians, 44% of obstetricians and gynaecologists felt depressed or burnt out, 18% indicated their wellbeing declined after the COVID-19 outbreak (Martin & Koval, 2021).

An urgent need to address the health and wellbeing of O&G DiT was identified during Melbourne’s second state-wide lockdown. In response, FRANZCOG (Fellowship of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) DiT formed a leadership group, and with support from senior clinicians initiated the Monash Women’s leading kindness COVID-19 toolkit pilot project (the ‘leading kindness COVID-19 pilot’/‘the project’).

The broad project goals were to develop, deliver and evaluate a suite of COVID-19 pandemic–specific health and wellbeing resources for O&G DiT at Monash Women’s (MW). The project was informed by co-design principles of consultation, collaboration and participation (Burkett, 2012), was peer-led, and incorporated a peer-to-peer (P2P) learning model. With permission, material was utilised from the Pandemic Kindness Movement, which provides open-access to online resources designed by Australian healthcare clinicians to support healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (see https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/covid-19/kindness).

A mixed-methods evaluation strategy, incorporating quantitative and qualitative approaches was adopted. Quantitative findings based on the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) (Kristensen, 2005) and World Health Organisation Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) (Topp, 2015) found a reduction of burnout symptoms in O&G DiT at MW and increased feelings of wellbeing, (reported in Ward et al., n.d). The qualitative evaluation using the MSC technique, discussed here, supported these findings.

The Monash Women’s leading kindness COVID-19 toolkit pilot project

The project had four objectives, listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Monash Women’s leading kindness COVID-19 toolkit project objectives.

| 1. Provide immediate and practical tools and strategies to enhance the wellbeing of MW DiT working during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 2. Pilot the Monash Women’s leading kindness COVID-19 toolkit. |

| 3. Generate an evidence base, informed by qualitative and quantitative data, to inform future implementation. |

| 4. Assess the wellbeing and symptoms of burnout among MW DiT. |

Three online P2P workshops were held during which DiT identified goals to address their wellbeing needs at work (Table 2).

Table 2.

DiT wellbeing at work goals.

| 1. Getting enough rest during work hours and between shifts. |

| 2. Eating healthy foods and engaging in physical activity. |

| 3. Being aware of where to access mental health support at work. |

| 4. Keeping in contact with colleagues, family and friends. |

| 5. Advocating for management to create mentally healthy work structures. |

Adapted from: ‘Protecting your mental health and wellbeing as a healthcare worker’ (Beyond Blue, 2020).

Additional to identifying wellbeing goals during the workshops, DiT shared experiences, exchanged information and strategies for meeting basic needs, contributed to the development of the multi-format toolkit and provided feedback. Workshop topics covering basic needs, safety, love and belonging, esteem, contribution and leadership were derived from the ‘Pyramid of needs’ for health worker wellbeing (see aci.health.nsw.gov.au/covid-19/kindness), modelled on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943). A toolkit comprising COVID-19 pandemic–specific resources and strategies (Table 3) was developed and implemented.

Table 3.

Monash Women’s leading kindness COVID-19 toolkit elements.

| • P2P Workshops (described above) |

| • Posters summarising key workshop messages |

| • Hydration stations providing water, juice and other refreshments |

| • Development of the Monash Women’s DiT COVID-19 ToolKit app |

| • Reorganisation of doctors’ office space |

| • Physically distanced social activities (via Zoom Cloud Meetings) coordinated in partnership with Monash Women’s trainee association |

| • Meetings with senior registrars to develop communication and leadership skills |

| • Senior registrar education: role and responsibilities |

| • Ongoing formalised leadership skill training |

| • Development of protocol for dealing with distressed DiT |

| • Collection and implementation of feedback and suggestions for improvement |

| • Promotion of ‘leading kindness’ programme to O&G leadership team, the Newborn unit and Monash Health Intern education co-ordinator |

| • Mixed-methods evaluation strategy: Quantitative using validated burnout and wellbeing scales and qualitative using MSC. |

Evaluation strategy

The evaluation strategy included quantitative measures to assess wellbeing and burnout at three time points (pre and post) using CBI (Kristensen, 2005) and WHO-5 (Topp, 2015; Ward et al., n.d). Qualitative evaluation utilising the MSC technique involved gathering stories of change post-project to inform future directions by learning about participants’ experience and the nature and significance of changes.

The Most Significant Change technique

The MSC technique prioritises participants’ experience of important changes related to a programme. The evaluation process is about learning, rather than accountability and aims to be developmental, empowering and enabling (Davies & Dart, 2005). Success is not measured against programme goals; instead, emergent outcomes and value placed on significant changes form the focus of inquiry. MSC is particularly useful for: understanding the nature of change through participants’ voices (Tonkin et al., 2021; Limato et al., 2018), identifying unintended programme outcomes (Willetts & Crawford, 2007) and enabling stakeholders to articulate and focus on what they find most important (Shah, 2014). Basic steps, referred to as ‘the data cycle’, include identification of required data, collection of stories of change, selection of a most significant change story (or stories), analysis of key themes and communication of outcomes (Dart & Davies, 2003; Willetts & Crawford, 2007).

‘Domains of change’ may be identified, to assist in gathering, sorting, selecting and analysis. These are ‘broad, fuzzy categories’, for example, ‘personal change’, ‘organisational change’ and ‘other changes’ (Davies & Dart, 2005, p. 17). Determining domains prior to story collection is useful for complex projects involving many participants and multiple stories but is unnecessary for smaller samples (Davies & Dart, 2005), such as the ‘leading kindness COVID-19 pilot’.

The MSC technique uses purposive sampling, gathering stories from programme beneficiaries in semi-structured interviews. Broad open questions prompt exploration of significant changes arising from the intervention. Stories drawn from interview data are prepared and verified by storytellers before collation and assessment by a stakeholder panel that usually aims to choose one story encapsulating the most significant change. Key themes emergent from inductive analysis of all stories and selection panel discussion are also often captured. An important principle of MSC is that ‘the central aspect of the technique is not the stories themselves, but the deliberation and dialogue that surrounds the process of selecting significant changes’ (Dart & Davies, 2003, p. 138). This focus on the content of discussion and debate underpins the rationale for encouraging stakeholders to discuss and seek agreement on one most significant change story.

Designed to be adaptable and evolving, evaluators using MSC are invited to explore creative variations for specific contexts (Davies & Dart, 2005). Fundamentally a narrative method, MSC garners rich qualitative data and is more complex than it seems (Willetts & Crawford, 2007). While sometimes used as a sole evaluation tool (see, for example, Aisiri et al., 2020), triangulation with quantitative methods is strongly recommended (Davies & Dart, 2005; Ho et al., 2015; Rabie & Burger, 2019).

Most significant change and programme evaluation

Introducing programmes to build resilience at the individual level is an established organisational response to enhancing staff wellbeing; however, little has been published on efficacy (Comcare, 2010; Heath et al., 2020). Our literature review found no articles on using the MSC technique to evaluate workplace wellbeing programmes.

Even so, MSC has been widely applied to evaluation projects within Australia and internationally; however, the majority are described in grey literature, which can be difficult to access (Tonkin et al., 2021; Willetts & Crawford, 2007). Some examples appearing in academic publications include a professional development initiative for Australian teachers (Heck & Sweeney, 2013); customer perceptions of a transport subsidisation programme in South Africa (Rabie & Burger, 2019); and water and sanitation projects in Laos (Willetts & Crawford, 2007).

The centrality of storytelling as the data gathering method makes MSC well suited for evaluating healthcare programmes across various cultural contexts, particularly those targeting change at a personal level (Tonkin et al., 2021). Examples include promotion of childbirth spacing in Nigeria (Aisiri et al., 2020), maternal community health worker training in Indonesia (Limato et al., 2018), a medical education initiative to increase healthcare worker retention in sub-Saharan Africa (Connors et al., 2017), and cultural safety training for Colombian medical students (Pimental et al., 2021).

Reasons given for choosing the MSC technique in these evaluations include its participatory nature, the focus on participant experience, provision of insight into how change occurred, and ability to capture unintended outcomes. A key strength cited is the potential for storytelling to contribute to empowerment and further the change process (Aisiri et al., 2020; Connors et al., 2017; Limato et al., 2017; Tonkin et al., 2021).

Most significant change and the evaluation of the ‘COVID-19 leading kindness pilot’

The MSC technique complemented the project’s participatory principles and was chosen to learn about participants’ experiences and perceptions of change. A reference group comprising the project leadership team and two evaluators provided advice on sample recruitment, time frame and story gathering and selection processes. Subsequently this group and three senior clinicians met and agreed on communications, recruitment, guiding questions, sampling and story gathering.

The project was funded by the Monash Health Foundation. Approval to implement and evaluate the pilot was granted in accordance with the NHMRC Ethical considerations in Quality Assurance and Evaluation Activities (2014) guideline (QA/68545/MonH-2020-230841 [v2]).

It was decided targeted respondents would be O&G DiT who participated in at least one workshop. These DiT (n = 17) were approached because, in addition to being beneficiaries of wellbeing strategies introduced to the organisational environment (see Table 3), they had engaged with the programme design through workshop participation, with some being peer-presenters. Emails were sent by the leadership team outlining the evaluation purpose and inviting expressions of interest. Invitees were informed about the evaluation purpose and process, including the nature of MSC, how their interview would be used, and strategies to protect their identity. They were able to contact the evaluators directly, to protect confidentiality. Nine acceptances were received.

Guiding questions were provided prior to interview, which asked how participants were feeling before the ‘leading kindness COVID-19 pilot’, how they were affected personally and professionally by the pandemic, their experience of elements of the toolkit, the most significant change for them (positive or negative) and reasons why, and suggestions for future programmes. Interviews occurred at mutually convenient times using Zoom cloud meetings (Zoom) between 8 December 2020 and 4 January 2021.

Interview sessions commenced with discussion of the MSC process and ethical considerations, and confirmation of consent to participate and record the interview and generate a transcript. Respondents were advised their names would be concealed, their story would be sent to them for verification before inclusion in selection, and they could end participation at any time prior to the story selection meeting. It was explained that while every effort would be made, anonymity could not be guaranteed. Participants were advised evaluators only would access the recording and transcript, which would be securely stored and deleted on completion of the evaluation.

Following the interview one-page stories of significant change were prepared by the evaluators drawing on interview notes, audio recordings and interview transcripts. Each story was de-identified and assigned a code. These were sent back to interviewees for verification, editing where necessary and approval to include in the selection process and arising publications. Following feedback from some interviewees who were concerned about being identified, the reference group decided to separate each story into two parts, ‘before’ and ‘after’ the introduction of the project, to further protect against recognition by selection panel members. Interviewees were notified and agreed with this adjustment. The ‘before’ stories were not included in selection. ‘After’ instalments containing stories of significant change, averaging 250 words, were presented to the selection panel, which comprised seven stakeholders: three leadership team members and four senior clinicians.

The session occurred via Zoom, lasted for 90 min and was facilitated by two evaluators, who did not participate in discussion or selection; one facilitated the selection process and one took notes and managed technology. All attended from individual remote locations. The session commenced with introductions, an overview of the ‘leading kindness COVID-19 pilot’, an explanation of MSC and the selection process that had been decided upon, and advice the meeting was being recorded and a transcript would be generated.

To establish context for the changes described one ‘before’ story was read with permission from the respondent, a composite summary of ‘before’ responses was shared. ‘After’ stories were posted on screen, one at a time. Panel members took turns reading them to the group, each member then indicated the story they believed described the most significant change and gave reasons for their choice. Discussion and open voting took place.

The selection process involved three phases: randomly dividing the nine stories into three groups of three (completed by evaluators prior to the panel); shortlisting at least one story from each group; and ultimately selecting one story from the shortlisted stories. The session concluded when consensus, through an open vote, was reached on one story, and individual reasons for supporting this choice were shared. The session was conducted without Zoom features such as breakout rooms or the polling feature to simplify the process.

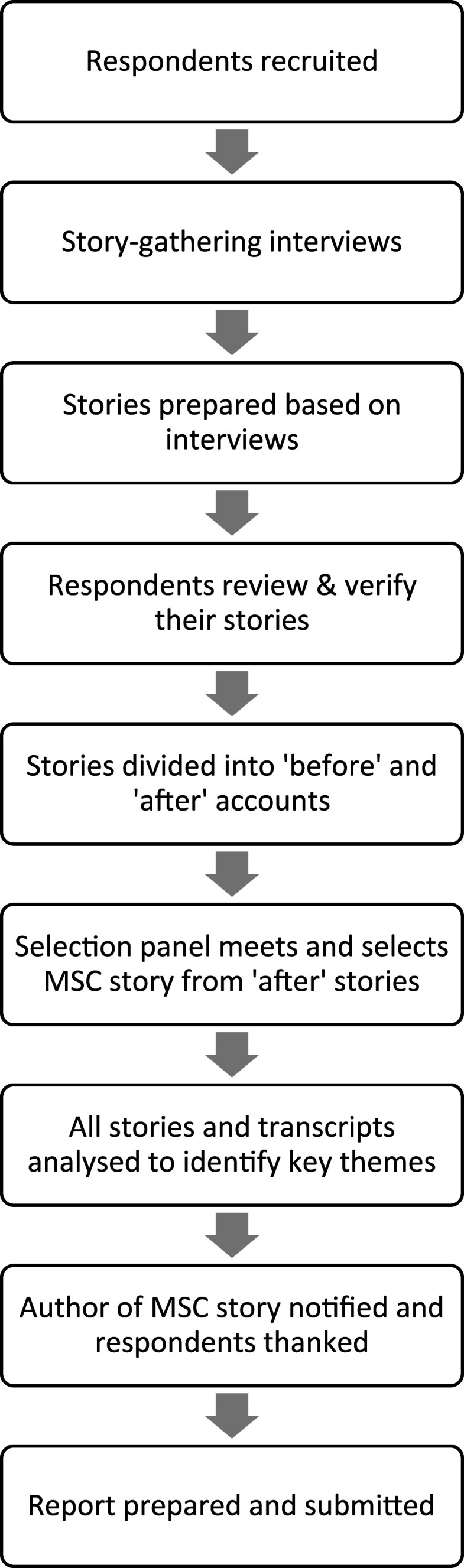

Following the selection panel, manual inductive analysis was conducted by the evaluators of all nine stories and the selection panel transcript, to capture emergent themes. All significant changes were extracted, sorted and categorised according to repeated changes, for example, ‘connection to colleagues’, ‘caring for self and others’, and ‘increased confidence’. Panel member’s reasons for their selections were also extracted and similarly categorised. A draft report was prepared and presented to the leadership group for comment, amendments, and approval prior to finalisation and being made available to participants. All interviewees were thanked for their participation in writing and the contributor of the selected story was notified of the outcome (Figure 1 provides a summary overview of the evaluation process.)

Figure 1.

Summary of evaluation process.

Learnings

The evaluation found the ‘COVID-19 leading kindness pilot’ was associated with a range of positive changes for Monash Women’s O&G DiT. This correlated with quantitative findings that burnout was reduced and wellbeing increased. How DiT were feeling prior to implementation of the wellbeing programme provides context for the changes experienced.

Before the COVID-19 leading kindness pilot

Prior to the ‘leading kindness COVID-19 pilot’ interviewees experienced the pandemic as all-consuming, and described feeling fearful for the future. COVID-19 protocols magnified existing stresses and increased the complexity of patient and staff interactions. There was concern about timely patient care. Managing personal protective equipment was difficult, with effects of dehydration, hunger, tiredness and claustrophobia. Keeping up with rapidly changing guidelines was frustrating and confusing; there were no precedents. Tele-health consultations and online handovers exacerbated the sense of distance between people; support networks had begun to fall away. Some respondents described ambivalence, needing social contact and at the same time socially withdrawing–not answering phone calls and emails. Others moved away from their homes to protect family members. Feeling overwhelmed and burnt out, DiT related concern about their mental health. At the same time, there was gratitude for employment and comfort in having a workplace to go to, because it offered structure, collegiality, and purpose. No one had lost hope; all were seeking ways to deal with the challenges.

The ‘difference that made a difference’

Drawing on the definition of the most significant change as ‘the difference that makes a difference’ (Davies & Dart, 2005, p. 62), the panel selected a story titled ‘Team cohesiveness’. The author described how the toolkit fostered a more supportive workplace culture by enabling basic needs to be met and breaking down hierarchical barriers within the O&G DiT team, explaining: ‘The program was an opportunity to address the things that make a cohesive team, that make us all better together.’

The story described how communicating vulnerabilities, caring for each other, and self-care translated into a positive workplace culture. Junior and senior colleagues connected; individual and collective confidence grew; teams were more able to meet patient needs, rise to challenges, and influence change.

The stakeholder panel valued how this story highlighted the role of the ‘COVID-19 leading kindness pilot’ in setting off a chain of changes. Changes at the individual level, which were supported by higher management and the organisation – such as DiT feeling cared for and more confident through having basic needs met, were linked with changes at the group level seen in more cooperative, cohesive teams, which in turn flowed on to better patient care.

Interconnecting themes

Five interconnected themes, derived from significant changes identified in the stories and panel transcript, culminated in making a positive difference to workplace culture: connection, caring, communication, confidence and cooperation. Table 4 lists these themes and the associated changes identified by participants.

Table 4.

Most significant change themes and changes.

| Most significant change | Theme | Changes |

|---|---|---|

| More caring, connected and supportive workplace culture | Connection | Senior DiT sharing vulnerabilities with junior DiT Flattening of hierarchy amongst DiT Knowing where to get help Workspace revamp-creating an organised, welcoming office space Creation of a space to talk |

| Caring | Caring for self and each other Meeting basic needs Improved patient care |

|

| Communication | Normalising open communication Giving and receiving feedback Increased interactions with colleagues |

|

| Confidence | In self and each other In leadership capacity In teams In ability to meet basic needs In advocating for change In asking for help |

|

| Cooperation | Co-design Peer leadership Peer-to-peer learning Working together |

Connection was the conduit to positive change. The workshop addressing the importance of meeting basic needs changed approaches to self-care and caring for each other; DiT were ‘more mindful of each other’s wellbeing’. The project created a ‘space to talk’ which allowed trainee doctors to ‘hear each other’. Senior DiT sought feedback from their supervisees; junior DiT were more confident seeking feedback. Communicating openly reduced feelings of intimidation, and trainees felt more connected: ‘hearing others talk about their experiences of not being okay and sharing my experience and feelings … made me feel more connected and less alone.’ All respondents described having more confidence about ‘not being okay’ and asking for help. Confidence in capacity to make a difference grew, ‘The most important change brought about by the wellbeing program for me was recognising my agency. I learned there were changes I could make.’ Cooperation was an underpinning factor, with the cooperation of senior clinicians’ imperative to success.

Domains of change

While domains of change were not developed prior to story gathering, understanding the structure of change emerged as important for future programme development because of the evident interdependence between change at all levels. While change at team and organisational levels was valued highly by some selection panel stakeholders, others emphasised the importance of personal change. Overall, it was acknowledged that change at the team level was enabled by changes at the personal level, which in turn cycled back to changes in team practices. The fundamental importance of organisational support and authorisation for these changes was highlighted.

Discussion

Considerations for future programmes

For selection panel stakeholders, the most significant change was a more caring and supportive workplace culture. Those who felt stressed and burnt out prior to the pilot felt more confident meeting their own and colleagues’ needs, and caring for patients. While the wellbeing programme was identified by all participants as the reason for these changes, effects of working together through pandemic conditions must also be acknowledged. Future programmes will need to reflect on how positive workplace culture can be sustained, particularly as COVID-19 continues to impact our lives and workplaces. The five emergent themes offer important signposts for consideration.

Peer leadership and the P2P learning model were identified as key to benefits received. Peer support initiatives to assist healthcare workers manage their wellbeing are a recognised need in the pandemic environment (Bridson et al., 2021). Our learnings strongly indicate success was based on peer leadership, and inclusive participatory processes such as co-design and P2P learning. While the inclusion of junior DiT as workshop presenters was imperative, senior DiT sharing their own experiences and vulnerabilities was particularly empowering, and fundamental to levelling power imbalances.

Successful implementation required endorsement and support at higher levels from Monash Health and Monash Women’s O&G leadership and clinical supervisors. Ensuring the wellbeing of frontline medical and healthcare workers during the pandemic requires organisational resources, including creating a positive and safe working environment, collegial support, respect and good communication (Forbes et al., 2020; Heath et al., 2020; Lou et al., 2021). An urgent need for an organisational response created a welcoming environment. Perceptions of urgency are linked to effectively introducing organisational change (Kotter & Cohen, 2002), and this programme was introduced amid acute awareness of the burden of the pandemic on healthcare workers’ physical and mental wellbeing. However, the need for safe working conditions exceeds COVID-19, and the pandemic may have brought to the fore pre-existing problems for DiT. Ignoring conditions that denied meeting basic needs at work, such as meal, hydration and shift breaks was no longer possible.

Implementation benefits and challenges

Sample size and protecting anonymity

A larger sample would have generated more stories for selection and analysis. Including O&G DiT who had not participated in workshops, but who had been exposed to elements of the toolkit in their working environment may have enhanced learnings.

Sharing personal stories in a small sample size (n = 9) where there were close working relationships meant anonymity could not be guaranteed. This was addressed by removing all identifying information from stories, disaggregating before and after stories and notifying participants of the possibility they may be identified. The small sample size and familiarity amongst interviewees also had distinct advantages, which flowed from positive changes brought about by the wellbeing programme. This was seen in the high level of caring, supportiveness and respect amongst respondents.

Timing

The pilot was conducted in the final quarter of the year, requiring story gathering and selection to take place between December 2020 and January 2021. This had consequences for recruitment as potential respondents and selection panel members were finishing contracts and/or going on annual leave. Using remote communication addressed this to an extent by providing more options for participating. This timing also meant only one selection session was possible, limiting stakeholder involvement.

Selection panel membership

To ensure representation from a range of stakeholders, including programme beneficiaries, organisational representatives, and programme leaders, the selection panel comprised MW O&G leadership, senior (supervising) DiT and junior DiT; which included interview participants. This presented possible issues, such as senior members unduly influencing selection, junior members feeling intimidated, and story contributors finding objectivity challenging. These concerns were addressed by careful facilitation, structured to minimise the possibility of those in senior positions (or others) dominating discussion, and ensuring everyone actively contributed to decision-making. Secondary analysis of all stories allowed inclusion of all participants’ stories in determining key significant change themes. Mitigating these challenges in future might be strengthened by including either a series of panels, or breakout groups within the selection panel involving stakeholders drawn from similar organisational levels. Rather than open voting, a closed ballot using the Zoom polling feature might also reduce potential hierarchical influences.

Considerations when using remote communication

Pandemic restrictions imposed limitations and presented opportunities for data gathering. Challenges mainly arose in relation to level of experience using remote communication for the MSC technique, the different visual and spatial contexts for interpreting nonverbal communication, loss of opportunity for informal exchanges with participants and selection panel members, and no access to site visits. That said, opportunity to develop expertise in using remote communication technologies for story gathering and selection emerged, and we see this as an important future option for evaluators using the MSC technique.

Pre-pandemic accounts of evaluations using the MSC technique do not generally specify if story gathering and selection processes were conducted in person. The emphasis on connection with programme beneficiaries in the field and stakeholder participation pre-supposes this as standard practice. Literature reviewed on using the MSC technique for evaluations in healthcare settings did not reveal any accounts of data gathered exclusively via videoconferencing. An emerging body of literature is now addressing the use of Zoom and other videoconferencing platforms in qualitative research. Boland et al. (2021) conducted a rapid review of the use of Zoom and Skype in qualitative research, concluding that, despite some areas for caution, ‘videoconferencing is a viable alternative to face-to-face research’ (Boland et al., 2021, p. 7).

Zoom was chosen principally because the evaluators already had experience using it for interviews and focus groups, and participants were familiar with its use. Other reasons included ease of use; quality of audio and visual display, and the option to record sessions and generate written transcripts. While there had been reports of some security risks associated with Zoom ‘bombing’, the account used, and meeting settings ensured interviews and the selection panel were secure (Chawla, 2020; O’Flaherty, 2020). Like others who report the intuitive advantages of using Zoom (Archibald et al., 2019; Gray, 2020) we had little trouble scheduling, inviting participants, or launching interviews and meetings. Features such as screen sharing, recording and creating transcripts were also unproblematic.

Adjustments were required to the way interviews and story selection were conducted. Visiting locations where programmes have been implemented assists forming connections with participants and verification of changes claimed (Davies & Dart, 2005). Boland et al. (2021), in their review of 66 papers exploring the use of videoconferencing in qualitative research found building rapport was a key concern. Although some qualitative researchers using Zoom have reported no obstructions to building rapport with interviewees (Archibald et al., 2019), or in drawing on nonverbal cues such as body language (Gray et al., 2020), at times it was challenging – for example, when connectivity was poor and participants were forced to opt for an ‘audio only’ connection. Establishing eye contact when videoconferencing was also an issue, as it can be difficult for the interviewer to determine if they are looking directly at the interviewee due to camera positioning. Namey (2020) found that distraction occurs when interviewers and participants can see themselves in their screens. That said, we felt meaningful connections were achieved with all nine interviewees.

Another difference emerged with the story selection session. When conducted in person these sessions usually take a minimum of 2 hours and include a break with refreshments, which facilitates informal exchanges and further reflections. Remote communication can foreshorten discussion and does not facilitate these relaxed, informal conversations (Boland et al., 2021; Namey, 2020). These effects were offset to some extent by the focus group format, and by engaging panel members in reading the stories. On the other hand, there were definite advantages. As others have found, finding mutually convenient interview times was easier (Gray et al., 2020), and it was time and cost effective (Archibald et al., 2019; Boland et al., 2021). Participants could be in a location where they felt more comfortable, and because panel members were able to join the selection session from various locations more could be present despite busy schedules (Boland et al., 2021; Gray, et al., 2020; Namey, 2020). Furthermore, potential power issues amongst selection panel stakeholders may have been moderated by not being in the same room. For example, dynamics created by seating arrangements became redundant.

Concluding comments

The evaluation found the ‘Monash Women’s COVID-19 leading kindness toolkit pilot’ brought about a positive shift in workplace culture, linked to relaxed hierarchy within the MW O&G DiT team. Five interconnected themes related to workplace practices contributed: connection, caring, communication, confidence and cooperation. Key factors supporting success were underpinning participatory principles of co-design, peer leadership, P2P learning, organisational support and senior leadership involvement. The findings were supported by quantitative evaluation using CBI and WHO-5, which found wellbeing was enhanced and burnout reduced (Ward et al., n.d). All interviewees considered the project highly valuable and wanted it repeated in the future. Learnings are informing a proposal for implementation of the programme and have supported the development of a start-up kit intended for organisations wishing to implement effective wellbeing programmes (see Ward et al., 2021).

Although conducting the MSC evaluation using Zoom presented minor challenges, there were definite advantages, with story gathering and selection not unduly compromised. The reflections of other evaluators on using the MSC technique under pandemic restriction conditions will make a valuable contribution to understanding how physical distancing requirements can be effectively overcome.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported by Monash Health Foundation.

ORCID iDs

Karen Crinall https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3643-9969

William Crinall https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5199-9606

References

- Aisiri A., Fagbemi B., Akintola O. A, Abodunrin O. S., Olarewaju O., Laleye O., Edozieuno A. (2020). Use of the most significant change technique to evaluate intervention in promoting childbirth spacing in Nigeria. African Evaluation Journal, 8(1), 1–7. 10.4102/aej.v8i1.426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald M. M., Ambagtsheer R. C., Casey M. G., Lawless M. (2019). Using Zoom Videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919874596. [Google Scholar]

- Blue B. (2020). Protecting your mental health and wellbeing as a healthcare worker. https://coronavirus.beyondblue.org.au [Google Scholar]

- Boland J., Banks S., Krabbe R., Lawrence S., Murray T., Henning T., Vandenberg M. (2021). Using Zoom and Skype for qualitative group research A COVID-19-era rapid review. Public Health Research and Practice, Online Early Publication. 10.17061/phrp31232112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridson T.L., Jenkins K., Allen K. G., McDermott B. M. (2021). PPE for your mind: A peer support initiative for healthcare workers. The Medical Journal of Australia, 214(1), 8–11. 10.5694/mja2.50886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkett I. (2012). An introduction to co-design. Knode. https://www.yacwa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/An-Introduction-to-Co-Design-by-Ingrid-Burkett.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chawla A. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) ‘Zoom’ application boon or bane. SSRN. 10.2139/ssrn.3606716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comcare (2010). Effective health and wellbeing programs. Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- Connors S. C., Nyaude S., Challender A., Aagaard E., Velez C., Hakim J. (2017). Evaluating the impact of the medical education partnership initiative at the university of zimbabwe college of health sciences using the most significant change technique. Academic Medicine, 92(9), 1264–1268. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart J.,, Davies R. (2003). A dialogical, story-based evaluation tool: The Most Significant Change technique. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(2), 137–155. 10.1177/109821400302400202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies R.,, Dart J. (2005). The ‘Most Significant Change’ (MSC) technique. A guide to its use. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4305.3606. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes M., Byromvan der Steenstraten L.I., Markwell A., Bretherton H., Kay M. (2020). Resilience on the run: An evaluation of a well-being programme for medical interns. Internal Medicine Journal, 50(1), 92–99. 10.1111/imj.14324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray L. M., Wong-Whylie G., Rempel G. R., Cook K. (2020). Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: Zoom video communications. The Qualitative Report, 25(5), 1292–1301. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4212 [Google Scholar]

- Heath C., Sommerfield A., von Ungern-Sternberg B.S. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1364–1371. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck D.,, Sweeney T. (2013). Using most significant change stories to document the impact of the teaching teachers for the future project: An Australian teacher education story. Australian Educational Computing, 27(3), 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. L., Labrecque G., Batonon I., Salsi V., Ratnayake R. (2015). Effects of a community scorecard on improving the local health system in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Qualitative evidence using the Most Significant Change technique. Conflict and Health, 9(27). https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-015-0055-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane L. (2021). Death by 1000 cuts': Medscape national physician burnout and suicide report 2021. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#1.' [Google Scholar]

- Kotter J. P.,, Cohen D. S. (2002). The heart of change. Real life stories of how people change their organisations. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen T. S., Borritz M., Villadsen E., Christensen K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress, 19(3), 192–207. 10.1080/02678370500297720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limato R., Rukhsana A., Magdalena A., Nasir S., Kotvojs F. (2018). Use of Most Significant Change (MSC) technique to evaluate health promotion training of maternal community health workers in Cianjur district, Indonesia. Evaluation and Program Planning, 66, 102–110. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou N. M., Montreuil T., Feldman L. S., Fried G. M., Lavoie-Tremblay M., Bhanji F., Kennedy H., Kaneva P., Drouin S., Harley J.M. (2021). Evaluations of healthcare providers’ perceived support from personal, hospital, and system resources: Implications for well-being and management in healthcare in Montreal, Quebec, during COVID-19. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 44(3), 319–322. 10.1177/01632787211012742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwell A. L.,, Wainer Z. (2009). The health and wellbeing of junior doctors: Insights from a national survey. The Medical Journal of Australia, 191(8), 441–444. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K. L.,, Koval M. L. (2021). Medscape Obstetrician & Gynecologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021. Medcape. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-obgyn-6013515#. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A. H. (1943). Preface to motivation theory. Psychosomatic Medicine, 5(1), 85–92. 10.1097/00006842-194301000-00012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Namey E. (2020). Can you see me now? My experiences testing different modes of qualitative data collection. R & E Search for Evidence. https://researchforevidence.fhi360.org/can-you-see-me-now-my-experiences-testing-different-modes-of-qualitative-data-collection [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty K. (2020). Here’s how people can ‘Zoom-bomb’ your chat. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kateoflahertyuk/2020/03/27/beware-zoom-users-heres-how-people-can-zoom-bomb-your-chat/?sh=4288d8c1618e [Google Scholar]

- Pimental J., Kairuz C., Merchán C., Vesga D., Correal C., Zuluaga G. (2021). The experience of Colombian medical students in a pilot cultural safety training program: A qualitative study using the Most Significant Change technique. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 33(1). 58–66. 10.1080/10401334.2020.1805323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabie B.,, Burger A. (2019). Benefits of transport subsidisation: Comparing findings from a customer perception survey and Most Significant Change technique interviews. African Evaluation Journal. 7(1). 10.4102/aej.v7i1.371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reuters (2021). Melbourne reopens as world’s most locked down city eases pandemic restrictions. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/melbourne-reopens-worlds-most-locked-down-city-eases-pandemic-restrictions-2021-10-21/. [Google Scholar]

- Shah R. (2014). Assessing the ‘true impact’ of development assistance in the Gaza Strip and Tokelau: ‘Most Significant Change’ as an evaluation technique. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 55(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/APV.12062. [Google Scholar]

- Shreffler J., Petrey J., Huecker M. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: A scoping review. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(5), 1059–1066. 10.5811/westjem.2020.7.48684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin K., Silver H., Pimentel J., Chomat A. M., Sarmiento I., Belaid L., Cockcroft A., Andersson N. (2021). How beneficiaries see complex health interventions; A practice review of the most significant change in ten countries. Archives of Public Health, 79(18). 18. 10.1186/s13690-021-00536-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp C. W., Østergaard S. D., Søndergaard S., Bech P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. 10.1159/000376585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M., Crinall K., McDonald R., Crinall W., Aridas J., Leung C., Quittner D., Hodges R.J., Rolnik D. (2000) ‘The kindness COVID-19 toolkit: a mixed methods evaluation of a workshop designed by doctors in training for doctors in training’. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M., McDonald R., Aridas J., Rolnick D. (2021). Start Up: Leading Kindness COVID-19 Toolkit. [Google Scholar]

- Willetts J.,, Crawford P. (2007). The most significant lessons about the Most Significant Change technique. Development in Practice, 17(3), 367–379. 10.1080/09614520701336907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]