Abstract

We report that astrocytic insulin signaling co-regulates hypothalamic glucose sensing and systemic glucose metabolism. Postnatal ablation of insulin receptors (IRs) in Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-expressing cells affected hypothalamic astrocyte morphology, mitochondrial function and circuit connectivity. Accordingly, astrocytic IR ablation reduced glucose-induced activation of hypothalamic Pro-opio-melanocortin (POMC) neurons and impaired physiological responses to changes in glucose availability. Hypothalamus-specific knock out of astrocytic IRs as well as postnatal ablation by targeting glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST)-expressing cells replicated such alterations. A normal response to altering CNS glucose levels in mice lacking astrocytic IRs indicated a role in glucose transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This was confirmed in vivo in GFAP-IR KO mice using positron emission tomography as well as glucose monitoring in cerebral spinal fluid. We conclude that insulin signaling in hypothalamic astrocytes co-controls CNS glucose sensing and systemic glucose metabolism via regulation of glucose uptake across the BBB.

Keywords: hypothalamus, astrocytes, insulin receptor, glucose uptake

In Brief

Insulin sensing by hypothalamic astrocytes co-regulates brain glucose sensing and systemic glucose metabolism.

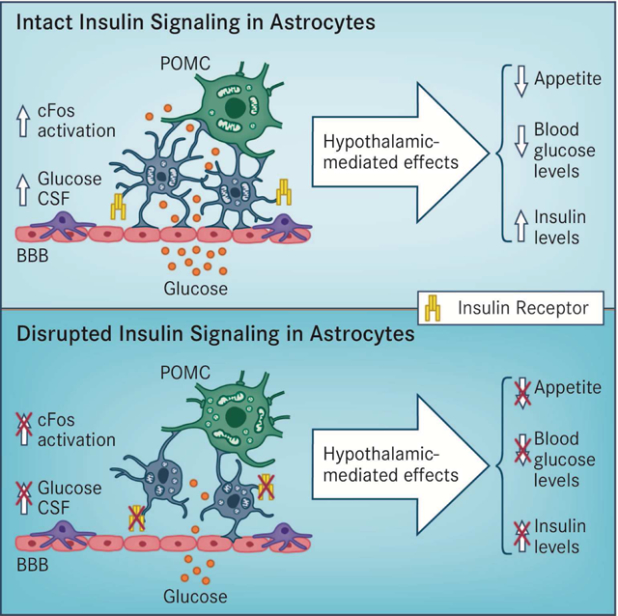

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Glucose availability in the Central Nervous System (CNS) is critical for neuronal function, and glucose levels in the brain regulate local neuronal activity as well as whole-body energy metabolism. Although glucose handling in the brain has been considered an insulin-independent process (Cranston et al., 1998; Hasselbalch et al., 1999), an open debate exists about the role of insulin action in controlling cerebral glucose metabolism. Several lines of evidence suggest that insulin signaling regulates central and systemic metabolic homeostasis (Bruning et al., 2000; Woods et al., 1979). However, the molecular mechanisms and the main cellular targets mediating central actions of insulin are far from being completely understood.

Interestingly, alterations in the insulin-CNS axis have been associated with the progression of some neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (Kleinridders et al., 2014; Koch et al., 2008), indicating that an appropriate control of central insulin signaling might be relevant for pathological conditions affecting neuronal integrity and function. IRs are widely distributed in the CNS (Havrankova et al., 1978) and abundantly expressed in epithelial cells in the choroid plexus and in brain endothelial cells (Frank et al., 1986). Cerebral blood vessels are ensheathed by endothelial cells that interact with adjacent astrocytes, the combination regulating the entry of nutrients such as glucose by changes in BBB permeability (Alvarez et al., 2013). Importantly, regulation of blood glucose supply to and within the brain is controlled via glucose transporter (GLUT)-1 (Abbott et al., 2006; Armulik et al., 2010). Although GLUT-1 is highly expressed along the BBB in both endothelial cells and astrocytes (Barros et al., 2007; Simpson et al., 2001), it is more abundant in astrocytes (Simpson et al., 1999). Astrocytes are the most abundant cells in the brain, and they provide a nurturing environment regulating all aspects of neuronal function including synaptic plasticity, survival, development, metabolism and neurotransmission, among others. In fact, astrocytes are able to respond to local levels of nutrients, acting as metabolic sensors and expressing specific receptors and transporters extending throughout their membrane surface (Garcia-Caceres et al., 2012). Consistent with this, astrocytes are located at the interface between vessels and neurons, putting them in a privileged position to control glucose fluxes between the periphery and the CNS. However, the possibility that insulin signaling in astrocytes plays a functional role in systemic metabolism has never been studied. We therefore used a series of glia-specific loss-of-function models to uncover the function of astrocytic insulin signaling in the brain, and more specifically for hypothalamic glucose sensing.

Results

Postnatal ablation of insulin receptors from astrocytes

To uncover the role of IRs in astrocytes, we used a Cre/lox approach to genetically remove IRs exclusively from human GFAP (hGFAP)- and GLAST-positive cells. Because glial cells act as neuronal progenitor cells during brain development (Goldman, 2003), we generated tamoxifen-inducible transgenic hGFAP-CreERT2 (Ganat et al., 2006) and knock-in GLASTCreERT2 (Buffo et al., 2008; Mori et al., 2006) mouse models to achieve time-specific IR flox/flox (f/f) deletion in adult mice. Using Rosa26 ACTB-tdTomato/EGFP (tdTomato/eGFP) reporter mice, we confirmed that Cre-mediated recombination occurred following intraperitoneal (ip) tamoxifen (Tx) injection (Fig.S1A). In agreement with previous studies demonstrating that both hGFAPCreERT2 (Kim et al., 2014) and GLASTCreERT2 (Mori et al., 2006) mouse models are suitable to achieve Cre-mediated recombination in astrocytes, we observed that virtually all of the Cre-recombined cells in the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) exhibited the stellated morphology characteristic of astrocytes as well as immunoreactivity for GFAP and S100β after Tx administration (Fig. S1B and Table 1). To demonstrate IR deletion in cells undergoing Cre-recombination, we crossed hGFAP-CreERT2:IRf/f and IRf/f mice with hGFAP-eGFP mice in which the fluorescent protein GFP was placed under control of the human GFAP promoter (Nolte et al., 2001). Using this reporter mouse model, we purified hGFAP-GFP+ cells from brains of adult mice by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and confirmed that IR expression was significantly reduced exclusively in the brains of hGFAP-CreERT2:IRf/f mice treated with Tx (named GFAP-IR KO mice; Fig.1A). IR mRNA expression was absent from GFP-targeted astrocytes in the hypothalamus of GLAST-IR KO mice (GLASTCreERT2:IRf/f mice injected with Tx) and crossed with tdTomato/eGFP mice; whereas IR mRNA was present in astrocytes of GLAST-IR WT mice (Fig.1B and S1C).

Table 1.

Related to Figure 1.

| Specificity (%/section) | Hypothalamus (%) |

| % GFAP/GFP | 61.8 ± 6.5 (n=11) |

| % S100β/GFP | 45.7 ± 2.4 (n=9) |

| Efficiency (%/section) | Hypothalamus (%) |

| % GFP/GFAP | 27.0 ± 8.5 (n=11) |

| % GFP/ S100β | 54.9 ± 3.3 (n=21) |

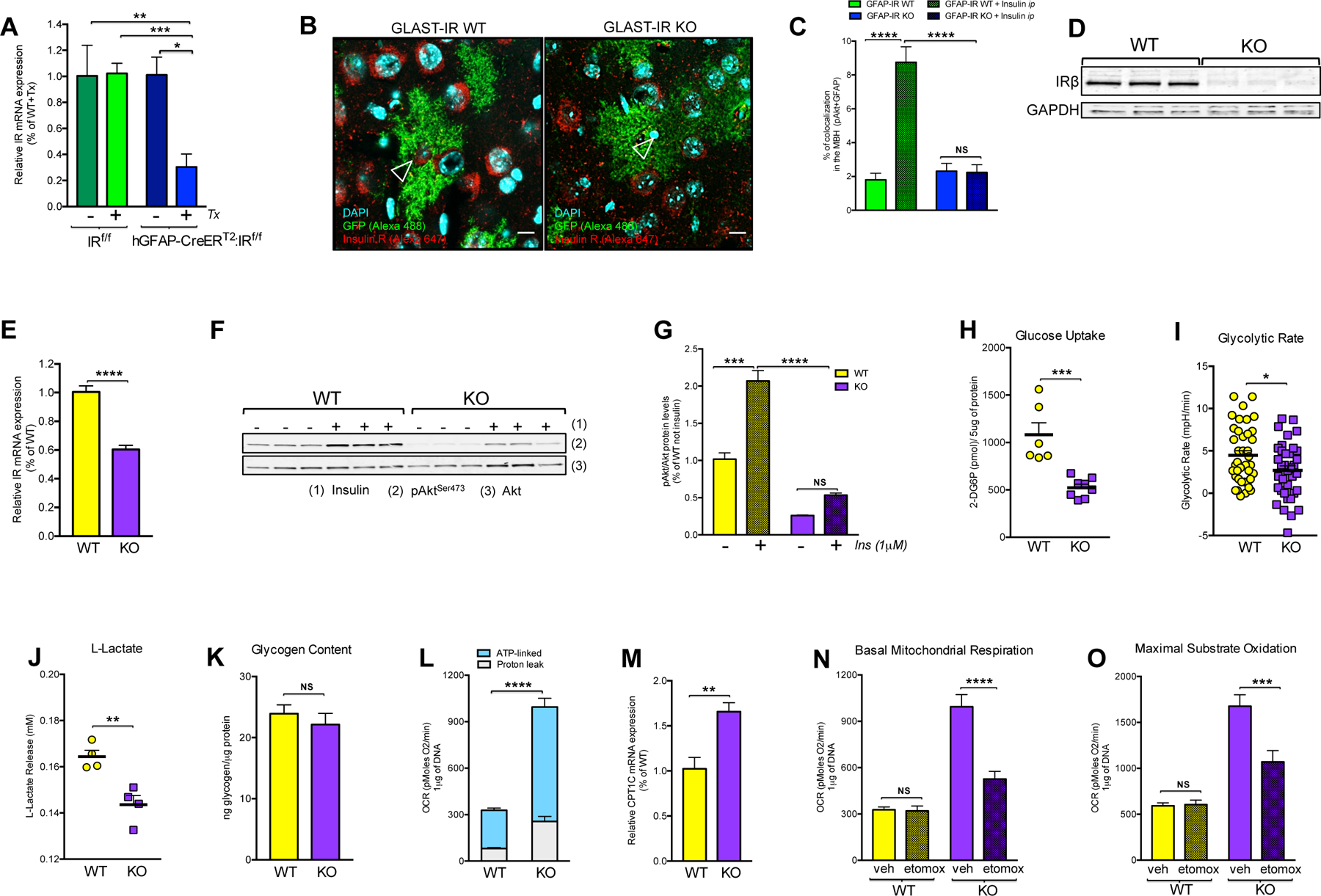

Figure 1. In vivo and ex vivo ablation of astrocytic IRs reduces insulin signaling and glucose availability in astrocytes.

(A) Insulin receptor (IR) mRNA expression levels in purified GFAP-positive cells from brains of adult IR flox/flox (f/f) mice or hGFAP-CreERT2:IRf/f mice after administration with (+) or without (−) tamoxifen (Tx) injection (n=3–10/group). (B) In situ hybridization combined with immunofluorescence for the visualization of IR mRNA (empty arrows; red, Alexa 647) in the GFP-expressing astrocytes under the promoter of GLAST (green fluorescence) from hypothalamic sections of GLAST-IR WT mice and GLAST-IR KO mice crossed with tdTomato/eGFP reporter mice (see also Fig. S1 and Table 1). (C) Percentage of positive colocalization of pAkt and GFAP-positive cells quantified in the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice 15 min after vehicle (saline) or insulin injection (ip; 3 IU/kg bw) (n= 4 mice/group)(see also Fig. S2 for peripheral tissue). (D) Protein levels of IRβ and GAPDH in primary hypothalamic astrocytes of IRf/f male mice treated with Adenovirus driven-GFP expression (WT; n=3) or driven-Cre recombinase with GFP expression (KO; n=3). (E) IR mRNA expression levels in primary hypothalamic astrocytes with (WT) or without (KO) IRs (n=6/ group). (F) Western blots and (G) quantification of the ratio between phosphorylated Akt in Serine 473 (pAktSer473) and total Akt protein levels in primary hypothalamic astrocytes with (WT) or without (KO) IRs 5 min after vehicle or insulin stimulation (1μM; n=3/group). (H) Cellular accumulation of 2-DG6P (in pmol/5 μg of protein; n=6–8/group), (I) glycolytic rate (n=35 replicates/group from 4 different experimental cultures), (J) L-Lactate production levels in medium (in mM; n=4/group) and (K) glycogen content (ng of glycogen/μg of protein; n=4/group) in primary hypothalamic astrocytes with (WT) or without (KO) IRs. (L) Basal mitochondrial respiration (OCR; pMoles of oxygen/min per 1 μg of DNA: n=35 replicates/group from 4 different experimental cultures) and (M) CPT1C expression levels (n=4/group) in primary hypothalamic astrocytes with (WT) or without (KO) IRs. Etomoxir effect on (N) basal mitochondrial respiration (OCR) or (O) maximal substrate oxidation (pMoles of oxygen/min per 1 μg of DNA) in hypothalamic astrocytes with (WT) or without (KO) IRs treated with vehicle (veh) or etomoxir (etomox: 40 μm) (n=12–36 replicates/ 4 different experimental cultures) (see also Fig. S3A). Akt: protein Kinase B; CPT1C: carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; GLAST: glutamate aspartate transporter; IR: insulin receptor; OCR: oxygen consumption rate; pAkt: phosphorylation in Serine 473 of Akt; Tx: tamoxifen. P values= ****p<0.0001; ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Finally, we confirmed that insulin treatment enhanced protein kinase B (Akt) activation in hypothalamic GFAP-positive cells of GFAP-IR WT mice (IRf/f mice treated with Tx); but not in GFAP-IR KO mice (Fig. 1C). In contrast, similar levels of Akt activation were observed in peripheral insulin-sensitive tissues (e.g., liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue) of mice with or without IRs in astrocytes (Fig. S2), demonstrating that the loss of IRs in astrocytes reduced insulin signaling activation uniquely in astrocytes of the brain.

Insulin Receptors control glucose availability in astrocytes

Next, we assessed the impact of IR ablation on glucose availability in astrocyte cultures from the hypothalamus of IRf/f male pups at postnatal day 1 in which IR deletion was induced by Adenovirus Cre-mediated recombination. First, we confirmed that adenoviral-based vectors mediated Cre-recombination widely in astrocyte cultures, succeeding in reducing IRβ protein levels (Fig. 1D), IR expression levels (Fig. 1E) and the ability of astrocytes to phosphorylate Akt following insulin administration (Figs. 1F and 1G). Moreover, the loss of IRs in astrocytes resulted in a lower glucose uptake upon stimulation with glucose (Fig. 1H), consistent with a reduced glycolytic rate (Fig.1I), lower GLUT-1 expression levels (WT: 1.00 ± 0.09, N=6 vs KO: 0.63 ± 0.09 % of WT values, N=6; p<0.02) and decreased L-lactate efflux (Fig. 1J) in those glial cells. However no differences were observed in cellular glycogen content among experimental groups (Fig.1K). Despite having a lower glycolytic flux, astrocytes without IRs exhibited higher basal mitochondrial respiration (Fig.1L), and this was associated with higher expression levels of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C (CPT1C), the key enzyme responsible for long-chain fatty acid transport into mitochondria (Fig.1M). To corroborate that the lack of IRs in astrocytes elevated mitochondrial fatty acid (beta)-oxidation for compensation of reduced glucose uptake, we used etomoxir to inhibit CPT1C and thus fatty acid oxidation. Indeed, etomoxir reduced basal mitochondrial respiration (Fig.1N) and maximal substrate oxidation (Fig.1O), without causing changes in glycolytic rate (Fig. S3A).

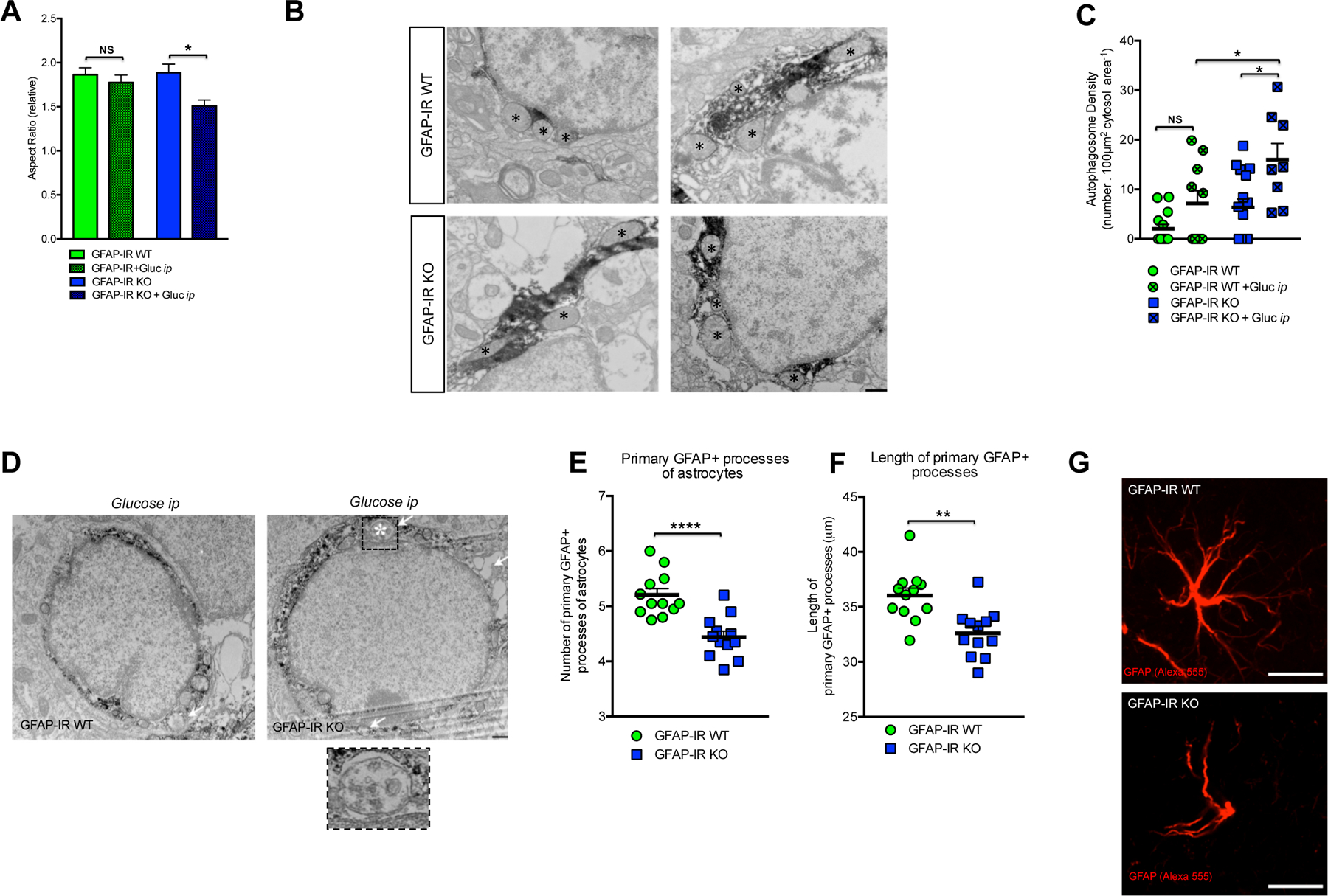

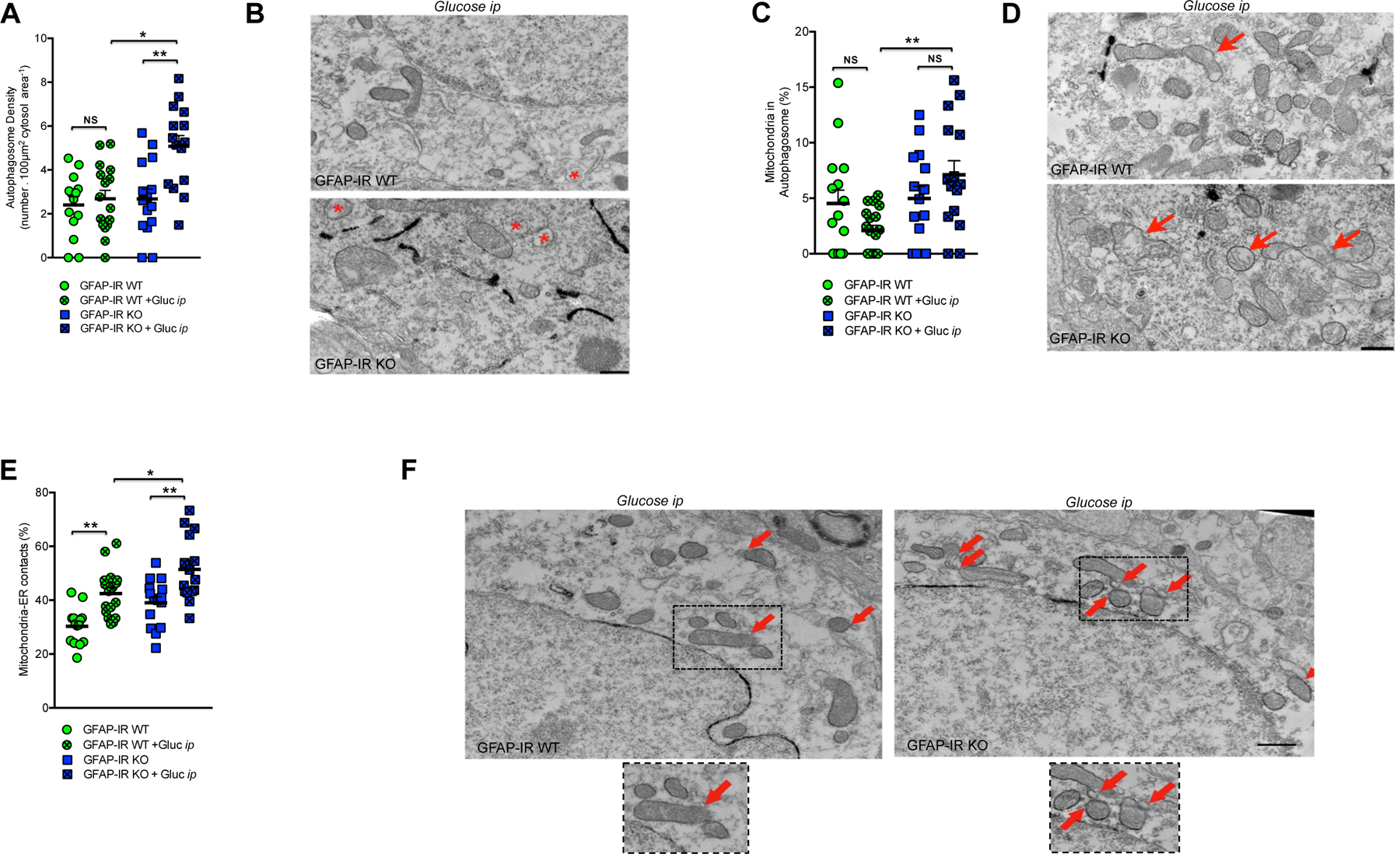

We next examined whether insulin signaling in astrocytes controls mitochondrial responses to glucose. We found that hypothalamic astrocytes of GFAP-IR WT mice responded to elevated systemic glucose levels by reducing the overall mitochondrial area; whereas there was no such significant change in hypothalamic astrocytes of GFAP-IR KO mice (Fig. S3B). Despite having no reduced cytosolic mitochondria area, astrocytes from the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR KO mice did have a reduced mitochondrial aspect ratio, a parameter reflecting mitochondrial length, due to fewer elongated mitochondria (asterisks; Fig. 2A and 2B), and an increase in the presence of autophagosomes (arrows; Fig. 2C and 2D) in response to elevated blood glucose. Both parameters remained unchanged in GFAP-IR WT mice.

Figure 2. Astrocytic insulin signaling regulates mitochondria-network and structural changes in hypothalamic astrocytes.

(A) Quantification and (B) electron microscopic images depicting the mitochondrial aspect ratio (asterisks → mitochondria) in astrocytes from the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice 30 min after ip glucose injection (n=3–4 brains per group) (see also Fig. S3B). (C) Quantification and (D) electron microscopic images depicting mitochondrial autophagosome density (arrow→ autophagosome) in astrocytes from the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice 30 min after ip glucose injection (n= 3–4 brains per group). Quantification of (E) the number of primary projections and (F) the length of their astrocyte processes in the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR WT versus GFAP-IR KO mice (n=20 brain sections/group)(see also Fig. S3C and S3D for the hippocampus). (G) High magnification image depicting the morphological differences between GFAP-positive cells (red, Alexa 555) from the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR WT mice versus those from GFAP-IR KO mice. GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; IR: insulin receptor. P values= ****p<0.0001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bars: (B and D): 500 nm; (G): 10 μm.

Astrocyte-specific loss of Insulin Receptors affects astroglial morphology

To verify a morphological impact following loss of astrocytic IRs in vivo, and given the effect of insulin-related peptides on astroglial differentiation (Toran-Allerand et al., 1991), we analyzed whether the morphology of hypothalamic astrocytes was affected following loss of IRs in vivo. While postnatal astrocyte-specific loss of IRs did not alter the total number of hypothalamic GFAP-positive cells (GFAP-IR WT: 93.7 ± 4.4: n=39 vs. GFAP-IRKO: 80.7 ± 5.6: n=39 astrocyte number /field), fewer (Fig. 2E) and shorter (Fig.2F) primary astrocyte processes were quantified in GFAP-IR KO mice compared to levels in GFAP-IR WT mice (Fig. 2G), indicating a potentially altered interaction with surrounding cells. A comparable reduction in the number of primary projections was also seen in extra-hypothalamic areas such as the hippocampus (Suppl. Fig. 3C); whereas no changes were detected in the length of the astrocyte processes in this area (Suppl. Fig. 3D).

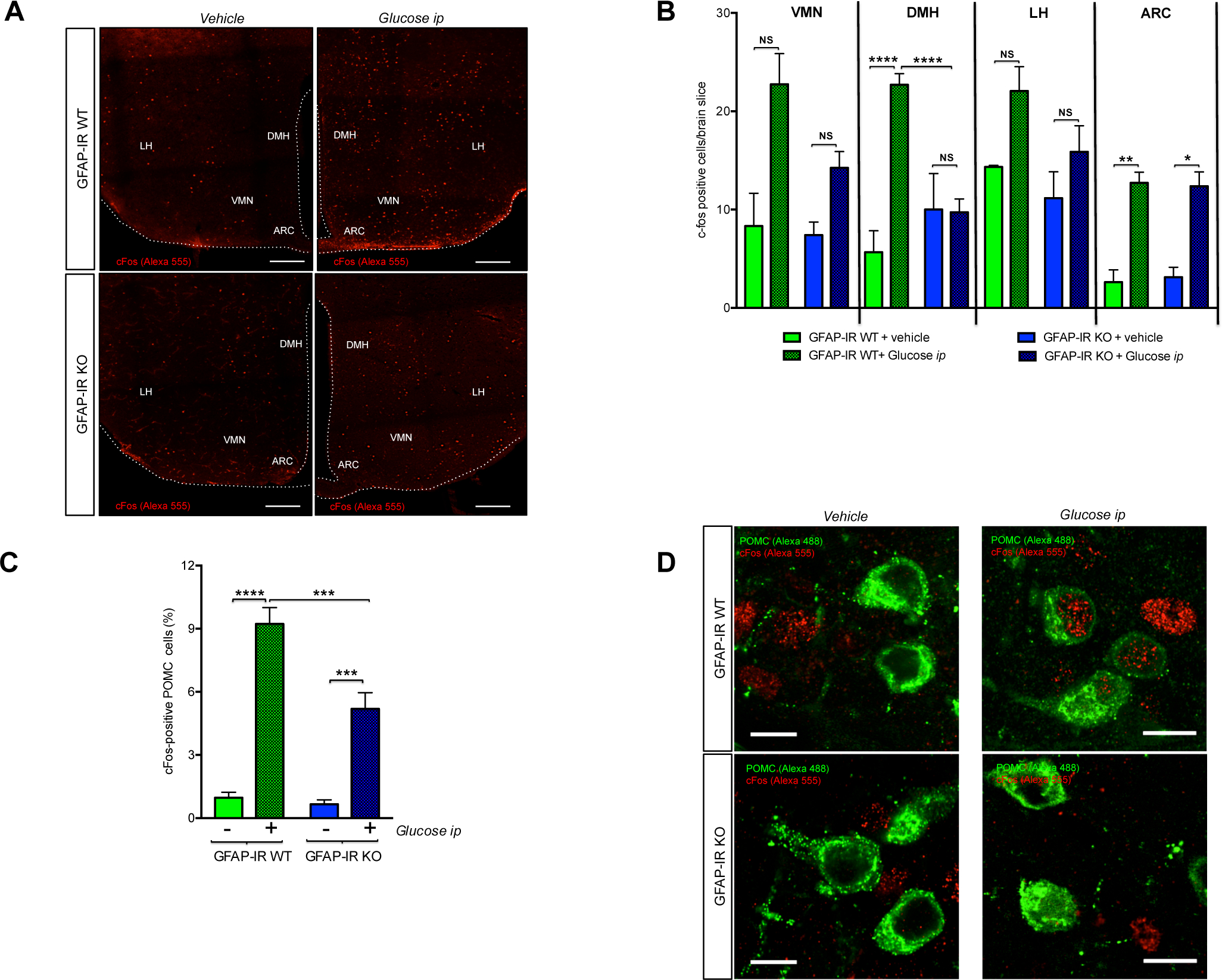

Astrocyte-specific loss of Insulin Receptors reduces glucose sensing in specific hypothalamic brain nuclei and POMC neurons

To evaluate glucose sensing in the hypothalamus in response to systemic glucose fluctuations, we examined c-Fos immunoreactivity in specific hypothalamic areas following ip glucose injection. GFAP-IR KO mice had a reduced number of glucose-induced, activated (c-Fos) cells in the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH) (Fig. 3A and 3B). No significant differences were observed in response to elevated blood glucose levels in the number of c-Fos immunoreactive cells in other hypothalamic areas analyzed, including the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), lateral hypothalamus (LH) and the arcuate nucleus (ARC) (Fig. 3B). Even though peripheral glucose injection increased the total number of c-Fos-labeled cells in the ARC of both groups, mice lacking astrocytic IRs had less of an increase in the number of glucose-activated POMC neurons (c-Fos-immunoreactive) in response to ip glucose (Fig. 3C and 3D).

Figure 3. Insulin receptors in astrocytes control glucose-induced c-Fos activation in hypothalamic POMC neurons.

(A) Brain sections depicting c-Fos immunoreactive cells (red, Alexa 555) in specific glucose-sensing hypothalamic nuclei of GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice 2 h after vehicle or ip glucose injection. (B) The number of c-Fos immunoreactive cells found in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMN), dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), lateral hypothalamus (LH) and arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) of GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice 2 h after vehicle or ip glucose (n=3–4 brains/group). (C) Analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in POMC neurons 2 h after vehicle or ip glucose injection in GFAP-IR WT mice versus GFAP-IR KO mice (n=3–4 mice/group). Data are expressed as percentage of total POMC cells having c-Fos immunoreactivity per section. (D) Images depicting POMC (green; Alexa 488) and c-Fos (red; Alexa 555)-positive cells in GFAP-IR WT mice vs GFAP-IR KO mice 2 h after vehicle or ip glucose injection. ARC: the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus; DMN: the dorsomedial hypothalamus; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; IR: Insulin receptor; LH: the lateral hypothalamus; VMN: the ventromedial hypothalamus. P values= ****p<0.0001; ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Scale Bar: (A): 200 μm; (D): 10 μm.

Astrocyte specific-loss of Insulin Receptors affects mitochondrial integrity and mitochondria-ER contacts in POMC neurons

Cellular adaptations to fluctuations in nutrient availability involve the regulation of mitochondrial function, a process that is intimately associated with changes in neuron-mitochondrial network complexity (Baltzer et al., 2010; Mandl et al., 2009). Indeed, we found that POMC neurons of mice lacking IRs in astrocytes had reduced mitochondrial density (Fig. S3E) and mitochondrial coverage (Fig. S3F) in response to high peripheral glucose levels whereas no differences were found in GFAP-IR WT mice. Both groups had an elevated mitochondrial aspect ratio in POMC neurons in response to ip glucose injection (Fig. S3G). GFAP-IR KO mice had an increase in the number of autophagosomes (asterisks; Fig. 4A and 4B) and disrupted mitochondria (arrows; mitochondria in autophagic processes) in the cytosol of POMC neurons (Fig. 4C and 4D).

Figure 4. Postnatal ablation of astrocytic IRs alters mitochondria-ER network adaptations to glucose in POMC neurons.

(A) Quantification and (B) electron microscopic images depicting autophagosomes (asterisk→ autophagosome) in POMC neurons of GFAP-IR WT mice and/or GFAP-IR KO mice (n=14–16 measurements from 3–4 mice/group). (C) Quantification and (D) electron microscopic images depicting mitochondria in autophagosomes (arrow→ disrupted mitochondrion or loss of mitochondrial membrane integrity) in POMC neurons of GFAP-IR WT mice and/or GFAP-IR KO mice (n=14–16 measurements from 3–4 mice/group) (see also Fig. S3E–S3G). (E) Quantification and (F) electron microscopic images depicting mitochondria-ER contacts (arrow mitochondrion in direct contact with ER processes) in the cytosol of POMC neurons of GFAP-IR WT mice and/or GFAP-IR KO mice (n=14–16 measurements from 3–4 mice/group). GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; IR: insulin receptor; POMC: pro-opio-melanocortin. P values= **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bars: 500 nm.

Finally, we examined the number of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondrial contacts of POMC neurons, contacts which are essential for structural support and functional interorganellar communication regulating Ca2+ homeostasis, metabolism of glucose, phospholipids, and cholesterol (Tubbs et al., 2014). After peripheral glucose administration, GFAP-IR KO mice had higher number of ER-mitochondrial contacts in POMC neurons relative to GFAP-IR WT mice (arrows; Fig. 4E and 4F). Taken together these findings suggest that the lack of IRs in astrocytes induces alterations in neural-mitochondrial network responses to glucose, which may impair POMC neurons to appropriately respond to cellular metabolic needs.

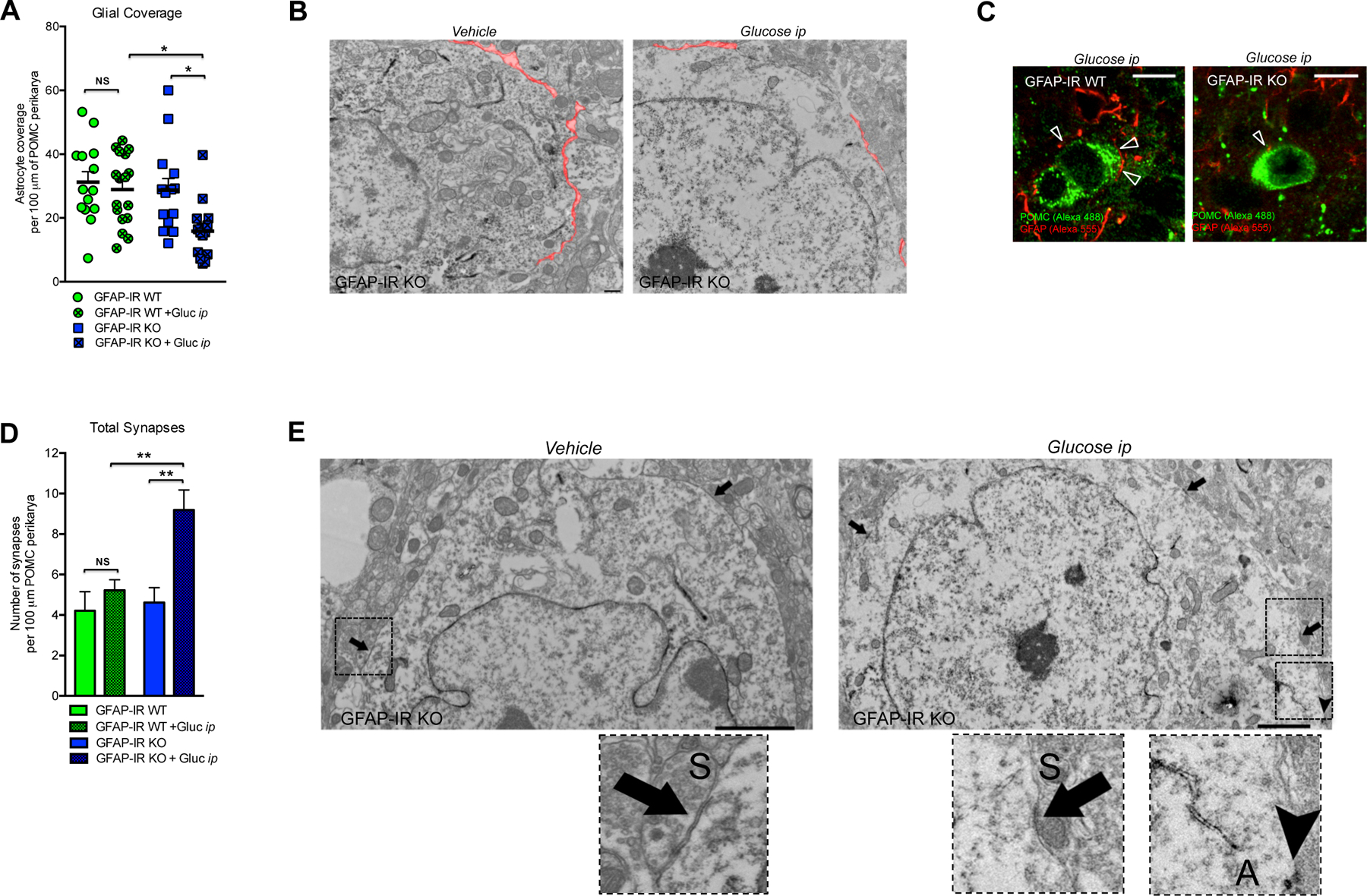

Astrocyte specific-loss of Insulin Receptors alters glial coverage remodeling and synaptic input organization on hypothalamic POMC neurons

To evaluate whether our observed changes in astrocyte morphology and c-Fos activation affect hypothalamic neural circuits controlling systemic glucose homeostasis, we analyzed the patterns of glial ensheathment of perikaryal membranes of immunoreactive POMC neurons in the hypothalamus. Mice lacking IRs exclusively in astrocytes responded to peripheral glucose injection by less glial coverage of POMC neurons than occurred in control mice (Fig. 5A), as indicated by using electron (Fig. 5B) or confocal microscopy (Fig. 5C; GFAP-IR WT + glucose ip: 26.81 ± 2.2; n=15 vs GFAP-IR KO + Glucose ip: 11.8 ± 1.9 % of astrocyte coverage per POMC cell; n=12; p<0.002). Finally, we analyzed the impact of glial coverage changes on the number and type of synaptic profiles on POMC neurons. There was an increase in the number of symmetric synapses (Fig. S3H) and no change in the number of asymmetric synapses (Fig. S3I) in response to peripheral glucose injection in both groups. However, the overall changes in the synaptic profile of POMC neurons in GFAP-IR KO mice resulted in an elevated number of total synapses on POMC perikarya (Fig. 5D and 5E).

Figure 5. Insulin signaling in astrocytes regulates glial coverage and synaptic profile of POMC neurons in response to elevated systemic glucose levels.

(A) Quantification and (B) electron microscopic images depicting glial coverage onto the membrane of hypothalamic POMC neurons of GFAP-IR WT mice and/or GFAP-IR KO mice 30 min after vehicle or ip glucose injection (n=3–4 mice/group). (C) Hypothalamic images depicting GFAP-labeled processes (red, Alexa 555) in direct contact (arrows) with the membrane of POMC neurons (green, Alexa 488) in the hypothalamus of GFAP-IR WT mice versus GFAP-IR KO mice 30 min after ip glucose injection. (D) Quantification and (E) electron microscopic images depicting the total number of synapses onto the membrane of hypothalamic POMC neurons of GFAP-IR WT mice and/or GFAP-IR KO mice 30 min after vehicle or ip glucose injection (n=3–4 mice/group). Symmetric synapses (S) → arrows. Asymmetric synapses (A) → head-arrow (see for synapses quantifications Fig. S3H and S3I). GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; IR: insulin receptor; POMC: pro-opio-melanocortin. P values= **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bars: (B): 500 nm; (C): 10 μm; (E): 2 microns.

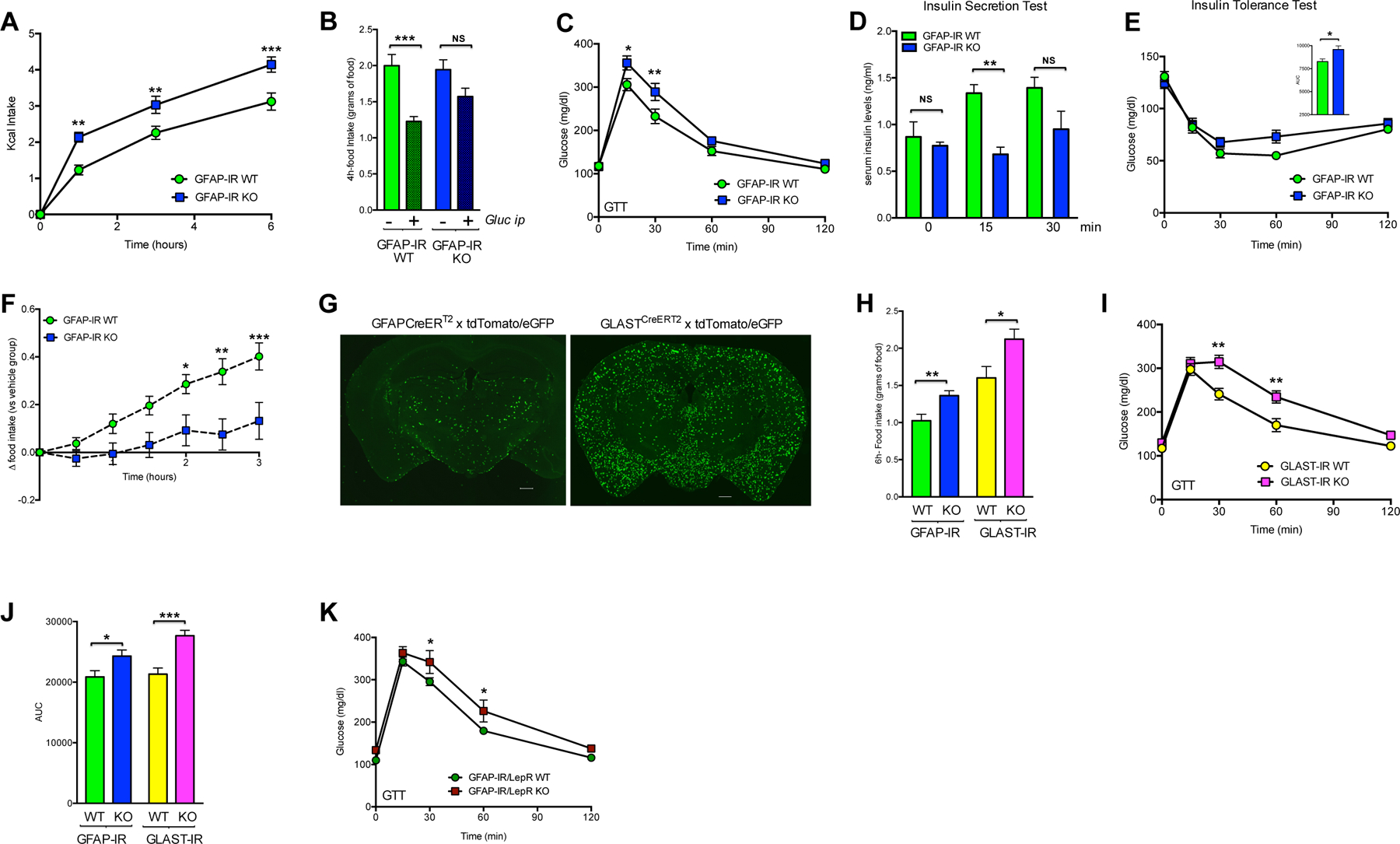

Astrocytic insulin signaling controls systemic glucose homeostasis

To determine whether astrocyte-specific IRs are involved in maintaining glucose homeostasis, we examined dynamic feeding behavior and glucose regulatory responses to altered systemic glucose availability. First, mice with or without astrocytic IRs were subjected to a fasting-induced hyperphagia paradigm to generate a physiological situation of increased glucose availability. GFAP-IR KO mice were unable to appropriately curb the hyperphagic response to fasting, likely due to insufficient availability or delayed appearance of glucose in the brain (Fig. 6A). Consistent with that possibility, GFAP-IR KO mice had a reduced suppression of fasting-induced hyperphagia in response to the administration of peripheral glucose (Fig. 6B), a finding which may reflect reduced activation of POMC neurons. We also observed that GFAP-IR KO mice failed to efficiently readjust systemic glucose levels when subjected to hyperglycemia induced by peripheral glucose injection (Fig. 6C). This effect was associated with a delayed response to increased peripheral insulin levels (Fig. 6D). Consistent with that, those mice exhibited a higher area under the curve (AUC) of blood glucose levels in response to peripheral insulin injection (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Insulin receptors in GFAP and GLAST-expressing astrocytes control CNS glucose sensing and systemic glucose metabolism.

(A) Food intake (Kcal) in response to fasting in GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice (n=8/group). (B) 4-h accumulated food intake in GFAP-IR WT and GFAP-IR KO mice after fasting and ip injection with vehicle or glucose (n=8/group). Blood glucose (C) and serum insulin (D) levels in GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice after peripheral glucose injection (n=8/group). (E) Insulin Tolerance Test in GFAP-IR WT mice versus GFAP-IR KO mice (n=8/group) after peripheral insulin injection. (F) Increase in food intake elicited by ip 2-DG in GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice (n=8/group). (G) Images (coronal sections) of brains corresponding to hGFAP-CreERT2 mice or GLASTCreERT2 mice, which were crossed with tdTomato/eGFP mice after tamoxifen injection. (H) 6-h accumulated food intake in the refeeding phase between GLAST-IR WT mice and GLAST-IR KO mice (n=5–8 mice/group) and between GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice (n=10–12 mice/group). (I) Blood glucose in GLAST-IR WT mice or GLAST-IR KO mice in response to ip glucose (n=5–8 mice per group). (J) Glucose Tolerance Test in GFAP-IR WT mice versus GFAP-IR KO mice (n=10–12 mice per group) and GLAST-IR WT or GLAST-IR KO mice (n=5–8 mice per group). (K) Blood glucose levels of GFAP-IR/LepR WT mice (n=12) versus GFAP-IR/LepR KO mice (n=5) in response to ip glucose. AUC: area under the curve; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; hGFAP: human glial fibrillary acidic protein; GLAST: glutamate aspartate transporter; GTT: glucose tolerance test; IR: insulin receptor; LepR: leptin receptor; 2DG: 2-deoxy-D-glucose. P values= ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bars: 500 μm.

Next, we evaluated feeding in response to a peripheral glucose deficiency elicited by the glucoprivic agent, 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) (Smith and Epstein, 1969). The expected physiological hyperphagic response was absent in mice lacking astrocytic insulin signaling (Fig.6F), demonstrating that astrocyte-specific loss of IRs impacts in vivo glucose metabolism.

GFAP-positive astrocytes only represent one sub-population of astrocytes in the brain. We assessed whether the functional role of astrocytic insulin signaling in regulating glucose metabolism is restricted to the GFAP astrocyte-specific population or is also relevant for other astroglial populations such as GLAST-expressing astrocytes. To accomplish that, we ablated IRs in astrocytes from adult GLASTCreERT2 mice (Fig. 6G), and replicated the systemic glucose metabolic phenotype. GLAST-IR KO mice had an exaggerated fasting-induced hyperphagia comparable to that observed when we targeted IRs of GFAP-expressing cells (Fig. 6H). In addition, those mice also had impaired regulation of systemic glucose levels in response to hyperglycemia (Fig. 6I). Thus, both astrocyte-specific KO models had a significantly increased glucose AUC when compared to their respective WT groups (Fig. 6J). Taken together, these findings confirm the relevance of a functional contribution of insulin signaling in astrocytes to systemic glucose control.

Mice lacking Insulin Receptors in astrocytes exhibit a systemic glucose metabolic phenotype that is not a direct consequence of mitochondrial alterations in hypothalamic astrocytes

To evaluate whether the alterations in systemic glucose metabolism may simply be due to mitochondrial alterations in hypothalamic astrocytes of GFAP-IR KO mice, we generated a mouse model in which we altered astrocytic mitochondrial function by ablating Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in GFAP-positive cells of adult mice (named GFAP-UCP2 KO). Mice lacking UCP2 in astrocytes had a higher overall mitochondrial area in the cytosol of hypothalamic GFAP-positive cells (Fig. S3J), and this was not associated with changes in their mitochondrial aspect ratio (aspect ratio; Fig. S3K and S3L). Despite mice having mitochondrial deregulation in astrocytes caused by the lack of UCP2, they did not exhibit altered glucose handling (Fig. S3M), as we had observed in GFAP-IR KO mice. Thus, astrocytic mitochondrial changes per se, are unlikely cause of altered glucose control of astrocyte-specific IR conditional KO mice, but rather represent an adaptive consequence of altered glucose availability.

Integration of energy-related signals in astrocytes contributes to regulate systemic glucose metabolism

Leptin and insulin are fundamental energy-related peripheral signals that have complementary yet distinct action in the brain. In order to dissect how both signals are integrated at the level of the astrocyte, we generated a specific adult double-knock out mouse model to simultaneously ablate both the insulin and leptin receptors (IR/LepR) in GFAP-positive cells of adult mice. Mice lacking both IR/LepR in astrocytes (hGFAP-CreERT2- IRf/f/LepRf/f treated with Tx) had a glucose intolerance phenotype compared to their control littermates (Fig. 6K). These mice also exhibited elevated basal blood glucose levels (GFAP-IR/LepR WT mice: 109.8 ± 3.4; n=12 vs GFAP-IR/LepR KO mice: 133.8 ± 6.8 mg/dl; n=5; p<0.004), thus not only showing replication, but enhancement, of the glucose metabolic phenotype of astrocyte-specific IR knock out mice. These findings corroborate that hormone signaling in astrocytes has an important and previously under-appreciated role in the control of systemic glucose metabolism.

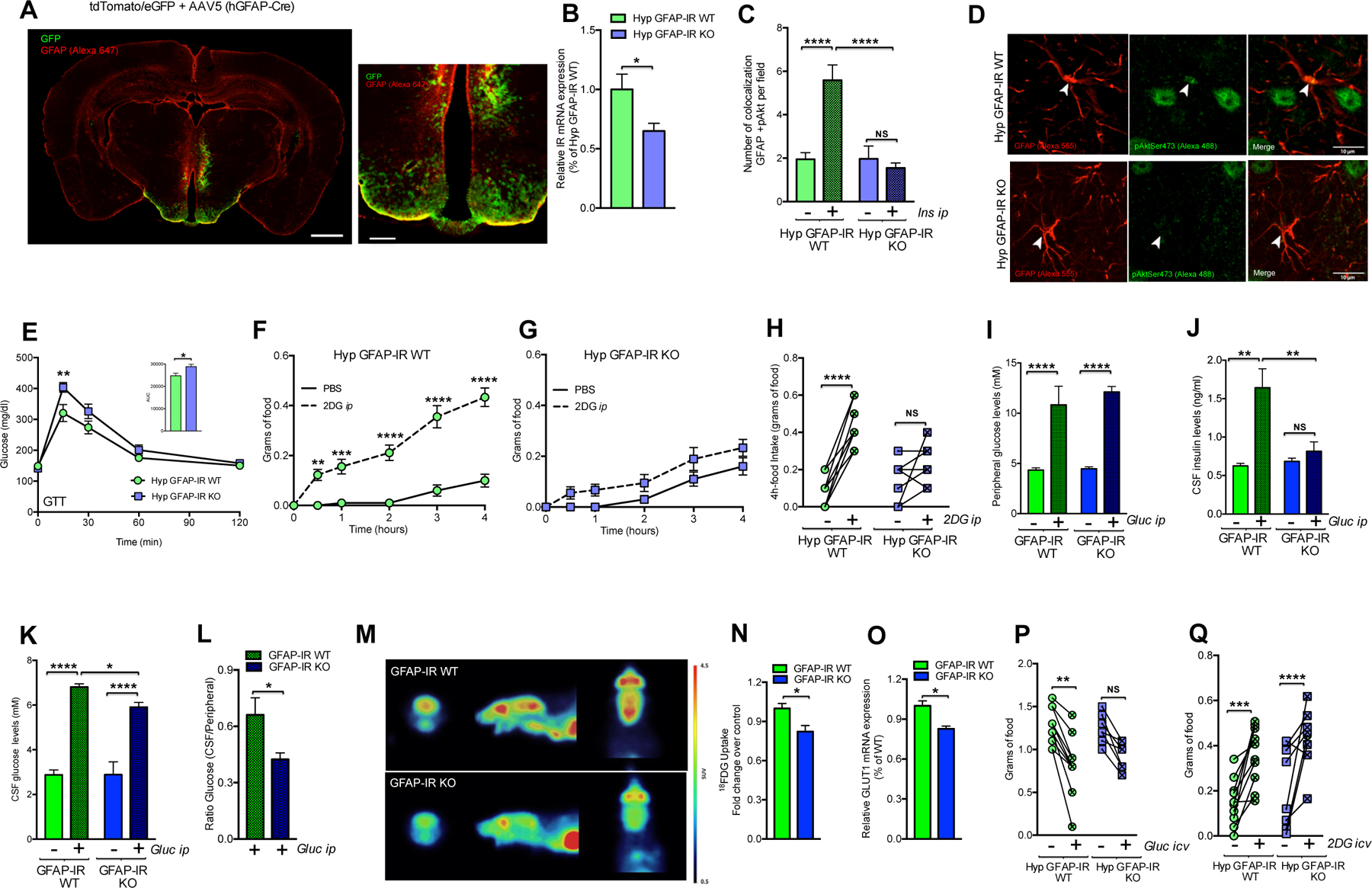

Insulin signaling in hypothalamic astrocytes is required for systemic glucose homeostasis

Given that GFAP expression is also observed in non-CNS tissues (Sofroniew and Vinters, 2010) and that the hypothalamus plays a pivotal role in the central control of glucose homeostasis, we used a viral-mediated Cre/lox system approach to delete IRs exclusively in astrocytes located in the MBH. Using tdTomato/eGFP mice, we confirmed that viral delivery of Cre-recombination in hypothalamic GFAP-IR KO mice occurred specifically in astrocytes located in the infected area of the hypothalamus, which also exhibited immunoreactivity to both GFAP and S100β (Fig. 7A and Fig. S3N and Table 2). Mice lacking IRs in hypothalamic astrocytes also had significantly decreased IR mRNA levels (Fig. 7B) and failed to increase activation of Akt in MBH astrocytes in response to ip insulin injection (Fig. 7C and 7D). Hypothalamic disruption of IRs in astrocytes of adult mice led to a phenotype that corresponded to that of GFAP-IR KO mice. Specifically, virus-assisted IR knock out in astrocytes of the MBH significantly impaired the systemic regulatory response to a peripheral glucose challenge (Fig. 7E). Consistent with that observation, there was a reduction in 2DG-induced hyperphagia in those mice compared with littermate controls (Fig. 7F–7H). Collectively these data suggest that insulin signaling in hypothalamic astrocytes is required for efficient brain glucose handling.

Figure 7. Hypothalamic insulin receptors in astrocytes regulate feeding responses to adapt to systemic glucose availability and mediate proper glucose and insulin entry to the brain.

(A) Mouse brain overview and high magnification depicting the localization of the area infected by AAV5 hGFAP-Cre (GFP-recombined cells under the control of the promoter of hGFAP) and showing GFAP immunoreactivity (red; Alexa 647) in tdTomato/eGFP mice (see also Fig. S3N and Table 2). (B) IR mRNA expression levels corresponding to the hypothalamic region containing virus-targeted astrocytes from C57BL6J mice (n=6) or IRf/f mice (n=5) crossed with tdTomato/eGFP mice, which were injected with AAV-hGFAP-Cre in the MBH. (C) Number of GFAP-positive cells that (co)localize with pAkt in the hypothalamus of IRf/f mice injected with AAV-hGFAP-GFP (Hyp GFAP-IR WT) or AAV-hGFAP-Cre mice (Hyp-GFAP-IR KO) in the MBH 15 min after vehicle (PBS) or insulin injection peripherally (3 U/kg bw; n= 4 mice/group). (D) Images depicting GFAP-positive cells (red; Alexa 555) and pAkt Ser473 (green; Alexa 488) in the hypothalamus of Hyp GFAP-IR WT mice versus Hyp-GFAP-IR KO mice. (E) Blood glucose in Hyp GFAP-IR WT mice (n=9) or Hyp-GFAP-IR KO mice (n=8) after ip glucose. Food intake over the following 4 h in Hyp GFAP-IR WT (F) or Hyp GFAP-IR KO (G) mice in response to vehicle or ip 2DG (n=9–10/group). (H) 4-h accumulated individual changes in food intake after vehicle or ip 2DG in Hyp GFAP-IR WT mice and Hyp GFAP-IR KO mice (n=9–10/group). (I) Glucose and (J) insulin content in blood, (K) glucose content in the CSF and (L) the ratio of glucose between CSF versus blood 30 min after ip vehicle or glucose in GFAP-IR WT mice versus GFAP-IR KO mice (n=4–8/group). (M) 18FDG accumulation in the brain of GFAP-IR WT mice versus GFAP-IR KO mice assessed by positron emission tomography (PET). (N) 18FDG fold change and (O) relative mRNA expression levels of GLUT-1 observed in the brain of GFAP-IR WT mice or GFAP-IR KO (n=4–8/group). (P) Individual changes of 4-h food intake after fasting and icv injection of vehicle (aCSF) or glucose (1 mg) and (Q) individual changes of 4-h food intake after icv injection of vehicle (aCSF) or 2-DG (1 mg) in mice with IR expression in astrocytes in the MBH (Hyp GFAP-IR WT mice; n=10) or without (Hyp GFAP-IR KO mice; n=10). AAV: adeno-associated virus; aCSF: artificial cerebrospinal fluid; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; GLUT-1: glucose transporter-1; GTT: glucose tolerance test; hGFAP: human glial fibrillary acidic protein; Hyp: hypothalamic; IR: insulin receptor; MBH: the mediobasal hypothalamus; 2DG: 2-deoxy-D-glucose; 18FDG: [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose. P values= ****p<0.0001; ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05. NS: No significant differences between groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bars: (A): left panel: 1 mm and right panel: 250 μm; (D): 10 μm.

Table 2.

Related to Figure 7.

| Specificity (%/section) | Hypothalamus (%) |

| % GFAP/GFP | 52.2 ± 3.9 (n=11) |

| % S100β/GFP | 66.2 ± 2.1 (n=19) |

| Efficiency (%/section) | Hypothalamus (%) |

| % GFP/GFAP | 59.4 ± 7.0 (n=8) |

| % GFP/ S100β | 53.4 ± 3.8 (n=16) |

Astrocytic insulin signaling is required for adequate insulin and glucose uptake into the brain

To assess if astrocytic insulin signaling, in addition to being required for the CNS control of peripheral glucose homeostasis, also participates in the brain control of systemic energy balance, we compared the energy metabolic phenotype between GFAP-IR KO and GFAP-IR WT mice. No differences in body weight or weekly food intake were detected on either standard chow or on a high-fat, high-sugar (HFHS) diet between groups (Fig. S3O). We next determined whether astrocytic insulin signaling may be directly required for CNS glucose availability. As a first step, we determined the impact of astroglial IR ablation on glucose uptake into the brain. Both GFAP-IR WT mice and GFAP-IR KO mice had comparably elevated systemic glucose levels after glucose challenge (Fig. 7I). However, GFAP-IR KO mice failed to increase insulin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and a lower increase in CSF glucose was observed (Fig. 7J and 7K). Accordingly, a lower glucose CSF/peripheral glucose ratio was found in mice lacking astrocytic insulin receptors exposed to elevated systemic glucose levels (Fig. 7L). To corroborate these observations, we used in vivo 18FDG positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to visualize and quantify glucose accumulation in the CNS. GFAP-IR KO mice had reduced brain glucose appearance in response to increased peripheral glucose levels (Fig. 7M and 7N). Interestingly, the reduced brain glucose availability in GFAP-IR KO mice was associated with lowered brain expression of glucose transporter (GLUT)-1 (Fig. 7O). Altogether these data indicate key role for astrocytic insulin signaling in mediating proper glucose and insulin entry to the brain.

Astrocytic insulin signaling is expendable for glucose handling within the brain

Astrocytes are well-positioned to act as primary regulators of local CNS blood flow, nutrient flux and synaptic function since they are in direct contact with both blood vessels and neurons (Magistretti and Pellerin, 1999; Nedergaard et al., 2003; Sofroniew and Vinters, 2010). To determine whether insulin signaling in astrocytes, in addition to regulating glucose influx into the brain, also directly modifies the responsiveness of hypothalamic neurons to CNS glucose availability, we assessed the feeding responses of mice to direct manipulations of CSF glucose concentrations. Although mice lacking IRs in hypothalamic astrocytes decreased their food intake following icv glucose injection, there was no interaction between genotype and the glucose response between groups (Fig. 7P). Accordingly, we found that, comparable to what occurred in hypothalamic GFAP-IR WT mice, hypothalamic GFAP-IR KO mice had a normal hyperphagic response when subjected to selective central glucose deprivation by icv 2DG injection (Fig. 7Q). These data indicate that the lack of insulin signaling in astrocytes does not affect glucose responsiveness or the counter-regulatory impact of hypothalamic neurons when glucose fluctuations originate within the BBB. Collectively, our data demonstrate that astrocytic insulin signaling regulates hypothalamic glucose sensing and systemic metabolism via the control of glucose uptake into the brain.

Discussion

Here we propose a novel model for the functional role of insulin action in the brain. We demonstrated that insulin signaling in astrocytes is required for efficient glucose uptake into the brain in response to changes in systemic glucose availability. In situations of impaired astroglial insulin signaling, such as in our genetically-engineered models or during diet-induced systemic insulin resistance, brain glucose uptake becomes less efficient, thereby compromising hypothalamic glucose sensing and consequently impairing CNS control of systemic glucose homeostasis. For decades, intense efforts have been made to dissect the exact neuronal circuits responsible for glucose sensing in the brain. A potential role for non-neuronal cells such as astrocytes, however, remained understudied. To uncover a potential role for insulin action on non-neuronal cells in the brain, we used a series of ex vivo and in vivo loss-of-function models to dissect IR function uniquely in astrocytes and to ascertain its relevance for the CNS control of systemic glucose homeostasis. We discovered that insulin signaling in astrocytes plays a key role in allowing efficient hypothalamic neuronal responses in order to appropriately counter fluctuations in systemic glucose availability. Genetic ablation of IRs from GFAP-expressing cells of adult mice altered hypothalamic cellular adaptations corresponding to changes in glucose accessibility in both astrocytes and POMC neurons. In response to elevated blood glucose levels, mice with reduced insulin signaling in GFAP-positive cells had hypothalamic astrocytes with fewer and smaller mitochondria but increased autophagy-related organelles relative to controls. These cellular adaptations are consistent with decreased intracellular glucose availability and lactate release caused by the reduced glucose-uptake capabilities of astrocytes lacking insulin receptors, as we had demonstrated ex vivo. Such metabolic response patterns may seem counterintuitive for astrocytes facing a relative intracellular glucose deficit, but have actually been previously observed, even in situations of glucose depletion (Brown and Ransom, 2007). Beta-oxidation of fatty acids was elevated by the lack of IRs, and was reflected in increased CPT1C expression and elevated etomoxir-sensitive mitochondrial respiration.

Changes in mitochondrial number and architecture were also found in hypothalamic POMC neurons, resulting in an elevated number of disrupted mitochondria and ER-mitochondrial contacts. Recent reports (Dietrich et al., 2013; Schneeberger et al., 2013) indicate that cells regulate mitochondrial function and architecture as a cellular mechanism of adaptation to energy deficits. That suggests that these glial and neuronal modifications of mitochondrial function might be caused by reduced cellular glucose availability. In addition, we found that unlike what occurs in control mice when exposed to high blood glucose levels, mice lacking IRs in astrocytes have altered hypothalamic glial and neuronal activity and remodeling, entailing changes in hypothalamic astroglial morphology. Further, a lower activation of POMC neurons was associated with a shift in their synaptic profile.

The CNS constantly responds to hormones and nutrients including glucose through a rapid rearrangement of hypothalamic connectivity, evoking the signal transduction necessary for regulating energy homeostasis (Pinto et al., 2004; Zeltser et al., 2012). Therefore, the differences in glial coverage and POMC activity and synaptology that we found might predict alterations in the regulation of feeding behavior and whole-body glucose metabolism that arise as a consequence of deficient astrocytic insulin signaling. Previous studies have indeed reported that changes in the glial distribution around hypothalamic POMC neurons can affect their capacity to respond to variations of glucose (Fuente-Martin et al., 2012).

To corroborate whether IRs in astrocytes are involved in maintaining glucose homeostasis, we examined dynamic responses to altered systemic glucose availability. As expected, mice lacking astrocytic IRs were unable to appropriately curb the normal hyperphagic responses to fasting or glucoprivation. Likewise, exogenous glucose did not suppress hyperphagia and failed to increase c-Fos activity in glucose-sensitive hypothalamic areas. Consistent with this observation, mice lacking astrocytic IRs were also unable to efficiently readjust systemic glucose levels when subjected to hyperglycemia, even when IRs in astrocytes were deleted selectively in the hypothalamus. Similar impairment of systemic glucose metabolism was also found after postnatal ablation of IRs in GLAST-expressing astrocytes. This astrocyte population partially overlaps with GFAP-positive astrocytes and GLAST is almost undetectable in neurons or oligodendrocytes (Mori et al., 2006). This independent set of studies shows that the functional relevance of astrocytic insulin signaling in regulating systemic glucose homeostasis is relevant for more than one population of astrocytes in the brain.

To explore further whether mice failed to curb overfeeding in response to glucose due to insufficient cellular sensing or inefficient uptake of glucose into the brain, we measured brain glucose accumulation in the CSF following peripheral glucose administration. Glucose and insulin availability were both reduced in the CSF in mice lacking astrocytic insulin receptors when subjected to elevated blood glucose levels. Likewise, brain glucose accumulation was also diminished when brain glucose levels where monitored using PET imaging. These observations were paralleled by reduced expression of GLUT-1, the predominant transporter responsible for facilitation of glucose transport across the BBB (Klepper and Voit, 2002).

Cerebral blood vessels are ensheathed by endothelial cells that interact with adjacent astrocytes, the combination regulating the entry of nutrients such as glucose by changes in BBB permeability (Alvarez et al., 2013). Although GLUT-1 is highly expressed along the BBB in both endothelial cells and astrocytes (Barros et al., 2007; Simpson et al., 2001), it is more abundant in astrocytes (Simpson et al., 1999). Previous reports indicate that GLUT-1 deficiency leads to restricted delivery of glucose into the brain (Barros et al., 2007; Klepper and Voit, 2002), suggesting that the reduced expression of GLUT-1 observed in the brain of mice without IRs in astrocytes likely decreases glucose transport across the BBB resulting in lower CSF glucose concentrations. Recently, alterations in GLUT-1 expression at the BBB were associated with the development of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimeŕs Disease (AD). In fact, early reductions in GLUT-1 at the BBB have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, promoting neuro-vascular dysfunction associated with AD progression (Winkler et al., 2015). Indeed, a link between AD and insulin resistance is currently emerging in a model where insulin signaling deficiencies contribute to develop the neuropathy and cognitive decline associated with the development of AD (De Felice and Ferreira, 2014; Ferreira et al., 2014). Therefore, insulin signaling/GLUT-1 interventions in astrocytes might represent useful therapeutic targets to prevent or slow down neurodegeneration and cognitive defects associated with the progression of AD. Finally, we found that insulin signaling in astrocytes is expendable for central glucose responsiveness when glucose fluctuations originate inside the BBB. Central manipulations of glucose reversed the phenotype of mice lacking astrocytic IR. That said, it is unknown if the long-lasting effects of a glucose-transport deficiency into the brain might increase the risk to elicit alterations in glucose-sensitivity. Collectively, our findings indicate that insulin signaling in astrocytes is required to interlink CNS glucose levels with systemic nutrient availability and is therefore indispensable for an appropriate regulation of systemic glucose homeostasis.

Conclusion

Here, we demonstrate that insulin signaling in astrocytes co-regulates behavioral responses and metabolic processes via control of brain glucose uptake to maintain systemic glucose homeostasis. Specifically, our findings uncover a role for insulin action in non-neuronal cells of the hypothalamus to regulate glucose entry into the CNS. Consistent with a model where astrocytes are functionally involved in both nutrient sensing and the CNS control of systemic metabolism, we recently reported that astrocytes respond to another afferent metabolic hormone, leptin. Astrocytic leptin deficiency also affects glial structure, ensheathment of hypothalamic POMC neurons and feeding responses (Kim et al., 2014). We therefore propose a model where similar to neurons; astrocytes respond directly to a plethora of nutrient and endocrine signals and in turn contribute to adjusting CNS control of systemic metabolism according to nutrient availability. This model may offer improved strategies for the discovery of novel therapeutics for metabolic as well as neurodegenerative diseases.

Material and Methods

Animals

hGFAP-CreERT2 are Tx-inducible transgenic mice in which the Cre transgene is expressed under the control of the hGFAP promotor. These mice were generated on a C57BL/6J background (provided by F.M. Vaccarino, Yale University School of Medicine) and were mated with mice having the sequence of the IR gene flanked by loxP sites (IRf/f) (generated by Ronald Kahn, Joslin Diabetes Center). Mouse cohorts for experiments were generated by mating IRf/f and hGFAP-CreERT2:IRf/f mice.

In parallel, GLAST CreERT2, a knock-in mouse line, was obtained and crossed with IRf/f mice. In this model, the CreERT2 allele is expressed in the locus of the control of the astrocyte-specific glutamate-aspartate transporter (GLAST) locus (Mori et al., 2006). Mice were generated by mating GLASTCreERT2 mice and GLASTCreERT2: IRf/f mice. All experiments with GLAST-specific KO mouse models were performed with the GLASTCreERT2 allele in heterozygotes.

To evaluate whether astrocytic mitochondrial or energy-signals deregulation causes systemic glucose metabolic alterations, we crossed hGFAPCreERT2 mice with UCP2f/f mice (Jackson Laboratory, Stock No. 022394, Bar Harbor, ME USA) or double combination of IRf/f mice and LepRf/f mice (McMinn et al., 2005). Cohorts of mice were generated by mating UCP2f/f mice and hGFAP-CreERT2:UCP2f/f mice or IRf/f:LepRf/f mice and hGFAP-CreERT2:IRf/f:LepRf/f mice, respectively.

To excise loxP sites by Cre recombination (see also Supplemental information), 6 weeks old male mice were injected daily with Tx (10 mg per kg of bw, ip) for 5 days. Tx (Sigma) was dissolved in sunflower oil at a final concentration of 10 mg/ml at 37°C, and then filter-sterilized and stored for up to 7 d at 4°C in the dark.

All mice were housed on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle at 22°C with free access to food and water, unless indicated otherwise. They were maintained on a pelleted chow diet (5.6% fat; LM-485, Harlan Teklad) until 12 weeks of age. Subsequently, the mice were either maintained on chow or switched to high-fat, high-sugar (HFHS: 58% kcal fat w/sucrose; Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) diet for 12 weeks. All studies were approved by and performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cajal Institute (Madrid, Spain), Yale University (New Haven, CT, USA) and the Helmholtz Centre Munich (Germany).

Glucose tolerance test (GTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT) and insulin secretion test (IST)

Mice were subjected to 6 h of fasting and then injected ip with glucose (2 g/kg bw of D-glucose in 0.9% saline) for the GTT and 0.75 U/kg bw of insulin (0.1 U/ml; Humolog Pen, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for the ITT. Tail-blood glucose levels (mg/dl) were measured with a handheld glucometer (TheraSense Freestyle) at the following time-points: 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after injection. For the IST, blood samples were collected at 0, 15 and 30 min after glucose injection (2 g of glucose /kg bw) for insulin determination by ELISA.

Feeding Experiments

For all feeding experiments, mice (3 months of age) were individually housed and fed a chow diet (see also Supplemental information).

Astrocyte-specific Cre-mediated recombination by adeno-associated Virus (AAV) bilaterally injected into the MBH

In order to ablate IRs specifically in astrocytes, we used AAV viral particles (serotype 2/5) expressing GFP or Cre protein under control of the hGFAP promoter (Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA, USA). We stereotaxically injected AAV-hGFAP-GFP (hypothalamic GFAP-IR WT) or AAV–hGFAP-Cre (hypothalamic GFAP-IR KO) particles bilaterally (2×109 viral genome particles per side) into the MBH of IRf/f littermates by using a motorized stereotaxic device (Neurostar, Tubingen, Germany). Stereotaxic coordinates were −1.5 mm posterior and −0.3 mm lateral to bregma, and −5.8 mm ventral from the dura. Surgeries were performed using a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg and 7 mg/kg, respectively) as anesthetic agents and Metamizol (50 mg/kg, s.c) followed by Meloxicam (1 mg/kg, on 3 consecutive days s.c.) for postoperative analgesia.

Primary Astrocyte Cultures Collection & Adenovirus-Cre in vitro infection mediated IR knockout

Hypothalami and cortices were extracted from IRf/f male mice at Postnatal Day 1 and were dissociated to single cells as previously described (Fuente-Martin et al., 2012).

Hypothalamic or cortical astrocyte cultures were seeded onto 6-well plates in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotic (penicillin 100 IU/ml and streptomycin 100 micro-g/ml) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were incubated with Adenovirus-GFP (AAV(5)-GFAP(2.2)-GFP, 1× 1013 gc/ml; WT) or Adenovirus-Cre-mediated deletion of allele with loxP sites coexpressed with GFP (AAV(5)-GFAP(2.2)-iCre, 1× 1013 gc/ml; KO) from Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX, USA) in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 1 % FBS for 6 h in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. To increase the binding of adenovirus to the cell surface, we added 0.25% of AdenoBOOST™ (Sirion Biotech, Planegg, Germany). After extensive washing in PBS, cells were incubated in DMEM-F12 with 10% FBS for 3 d.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. Two groups were compared by using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Two-way ANOVA was performed to detect significant interactions between genotype and treatment (tamoxifen, glucose, insulin or 2DG), and multiple comparisons were analyzed following Bonferronís post hoc tests. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed to detect significant interactions between genotype and time, and multiple comparisons were analyzed following Bonferronís post hoc tests. P values lower than 0.05 were considered significant. All results are presented as means ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Astrocytic IRs control glucose-induced activation of hypothalamic POMC neurons.

Hypothalamic IRs in astrocytes regulate CNS and systemic glucose metabolism.

Astrocytic IRs in mediating proper glucose and insulin entry to the brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Heicko Lickert and Silke Morin for helpful discussion and support, and Lewis Norris, Clarita Mergen, Veronica Casquero García, Olavi Järvinen and Nicole Wiegert for excellent technical assistance. This work was funded (in part) by the Helmholtz Alliance ICEMED – Imaging and Curing Environmental Metabolic Diseases, the Humboldt Foundation (MH. Tschöp), through the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association and Deutsches Zentrum für DiabetesForschung (DZD). DFG funding included SFB 1123 to MH. Tschöp as well as SFB 870 and SPP 1757 to M. Götz.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, and Hansson E (2006). Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 7, 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JI, Katayama T, and Prat A (2013). Glial influence on the blood brain barrier. Glia 61, 1939–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, et al. (2010). Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 468, 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltzer C, Tiefenbock SK, and Frei C (2010). Mitochondria in response to nutrients and nutrient-sensitive pathways. Mitochondrion 10, 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros LF, Bittner CX, Loaiza A, and Porras OH (2007). A quantitative overview of glucose dynamics in the gliovascular unit. Glia 55, 1222–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, and Ransom BR (2007). Astrocyte glycogen and brain energy metabolism. Glia 55, 1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, Klein R, Krone W, Muller-Wieland D, and Kahn CR (2000). Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science 289, 2122–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffo A, Rite I, Tripathi P, Lepier A, Colak D, Horn AP, Mori T, and Gotz M (2008). Origin and progeny of reactive gliosis: A source of multipotent cells in the injured brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 3581–3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranston I, Marsden P, Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, Sonksen P, Maisey M, and Amiel SA (1998). Regional differences in cerebral blood flow and glucose utilization in diabetic man: the effect of insulin. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 18, 130–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, and Ferreira ST (2014). Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as common molecular denominators connecting type 2 diabetes to Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 63, 2262–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich MO, Liu ZW, and Horvath TL (2013). Mitochondrial dynamics controlled by mitofusins regulate Agrp neuronal activity and diet-induced obesity. Cell 155, 188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira ST, Clarke JR, Bomfim TR, and De Felice FG (2014). Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10, S76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank HJ, Pardridge WM, Morris WL, Rosenfeld RG, and Choi TB (1986). Binding and internalization of insulin and insulin-like growth factors by isolated brain microvessels. Diabetes 35, 654–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuente-Martin E, Garcia-Caceres C, Granado M, de Ceballos ML, Sanchez-Garrido MA, Sarman B, Liu ZW, Dietrich MO, Tena-Sempere M, Argente-Arizon P, et al. (2012). Leptin regulates glutamate and glucose transporters in hypothalamic astrocytes. The Journal of clinical investigation 122, 3900–3913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganat YM, Silbereis J, Cave C, Ngu H, Anderson GM, Ohkubo Y, Ment LR, and Vaccarino FM (2006). Early postnatal astroglial cells produce multilineage precursors and neural stem cells in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 26, 8609–8621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Caceres C, Fuente-Martin E, Argente J, and Chowen JA (2012). Emerging role of glial cells in the control of body weight. Mol Metab 1, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S (2003). Glia as neural progenitor cells. Trends in neurosciences 26, 590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbalch SG, Knudsen GM, Videbaek C, Pinborg LH, Schmidt JF, Holm S, and Paulson OB (1999). No effect of insulin on glucose blood-brain barrier transport and cerebral metabolism in humans. Diabetes 48, 1915–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havrankova J, Roth J, and Brownstein M (1978). Insulin receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system of the rat. Nature 272, 827–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JG, Suyama S, Koch M, Jin S, Argente-Arizon P, Argente J, Liu ZW, Zimmer MR, Jeong JK, Szigeti-Buck K, et al. (2014). Leptin signaling in astrocytes regulates hypothalamic neuronal circuits and feeding. Nature neuroscience 17, 908–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinridders A, Ferris HA, Cai W, and Kahn CR (2014). Insulin action in brain regulates systemic metabolism and brain function. Diabetes 63, 2232–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepper J, and Voit T (2002). Facilitated glucose transporter protein type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency syndrome: impaired glucose transport into brain-- a review. Eur J Pediatr 161, 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch L, Wunderlich FT, Seibler J, Konner AC, Hampel B, Irlenbusch S, Brabant G, Kahn CR, Schwenk F, and Bruning JC (2008). Central insulin action regulates peripheral glucose and fat metabolism in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 118, 2132–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti PJ, and Pellerin L (1999). Cellular mechanisms of brain energy metabolism and their relevance to functional brain imaging. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 354, 1155–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl J, Meszaros T, Banhegyi G, Hunyady L, and Csala M (2009). Endoplasmic reticulum: nutrient sensor in physiology and pathology. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 20, 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMinn JE, Liu SM, Liu H, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P, Ludwig T, Boozer CN, and Chua SC Jr. (2005). Neuronal deletion of Lepr elicits diabesity in mice without affecting cold tolerance or fertility. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289, E403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Tanaka K, Buffo A, Wurst W, Kuhn R, and Gotz M (2006). Inducible gene deletion in astroglia and radial glia--a valuable tool for functional and lineage analysis. Glia 54, 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M, Ransom B, and Goldman SA (2003). New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends in neurosciences 26, 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte C, Matyash M, Pivneva T, Schipke CG, Ohlemeyer C, Hanisch UK, Kirchhoff F, and Kettenmann H (2001). GFAP promoter-controlled EGFP-expressing transgenic mice: a tool to visualize astrocytes and astrogliosis in living brain tissue. Glia 33, 72–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto S, Roseberry AG, Liu H, Diano S, Shanabrough M, Cai X, Friedman JM, and Horvath TL (2004). Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science 304, 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger M, Dietrich MO, Sebastian D, Imbernon M, Castano C, Garcia A, Esteban Y, Gonzalez-Franquesa A, Rodriguez IC, Bortolozzi A, et al. (2013). Mitofusin 2 in POMC neurons connects ER stress with leptin resistance and energy imbalance. Cell 155, 172–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Appel NM, Hokari M, Oki J, Holman GD, Maher F, Koehler-Stec EM, Vannucci SJ, and Smith QR (1999). Blood-brain barrier glucose transporter: effects of hypo- and hyperglycemia revisited. J Neurochem 72, 238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Vannucci SJ, DeJoseph MR, and Hawkins RA (2001). Glucose transporter asymmetries in the bovine blood-brain barrier. J Biol Chem 276, 12725–12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GP, and Epstein AN (1969). Increased feeding in response to decreased glucose utilization in the rat and monkey. The American journal of physiology 217, 1083–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew MV, and Vinters HV (2010). Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol 119, 7–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD, Bentham W, Miranda RC, and Anderson JP (1991). Insulin influences astroglial morphology and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression in organotypic cultures. Brain research 558, 296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs E, Theurey P, Vial G, Bendridi N, Bravard A, Chauvin MA, Ji-Cao J, Zoulim F, Bartosch B, Ovize M, et al. (2014). Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) integrity is required for insulin signaling and is implicated in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 63, 3279–3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler EA, Nishida Y, Sagare AP, Rege SV, Bell RD, Perlmutter D, Sengillo JD, Hillman S, Kong P, Nelson AR, et al. (2015). GLUT1 reductions exacerbate Alzheimer’s disease vasculo-neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. Nature neuroscience 18, 521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SC, Lotter EC, McKay LD, and Porte D Jr. (1979). Chronic intracerebroventricular infusion of insulin reduces food intake and body weight of baboons. Nature 282, 503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltser LM, Seeley RJ, and Tschop MH (2012). Synaptic plasticity in neuronal circuits regulating energy balance. Nature neuroscience 15, 1336–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.