Abstract

Clinical pharmacogenomic testing typically uses targeted genotyping, which only detects variants included in the test design and may vary among laboratories. To evaluate the potential patient impact of genotyping compared with sequencing, which can detect common and rare variants, an in silico targeted genotyping panel was developed based on the variants most commonly included in clinical tests and applied to a cohort of 10,030 participants who underwent sequencing for CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, DPYD, SLCO1B1, TPMT, UGT1A1, and VKORC1. The results of in silico targeted genotyping were compared with the clinically reported sequencing results. Of the 10,030 participants, 2780 (28%) had at least one potentially clinically relevant variant/allele identified by sequencing that would not have been detected in a standard targeted genotyping panel. The genes with the largest number of participants with variants only detected by sequencing were SLCO1B1, DPYD, and CYP2D6, which affected 13%, 6.3%, and 3.5% of participants, respectively. DPYD (112 variants) and CYP2D6 (103 variants) had the largest number of unique variants detected only by sequencing. Although targeted genotyping detects most clinically significant pharmacogenomic variants, sequencing-based approaches are necessary to detect rare variants that collectively affect many patients. However, efforts to establish pharmacogenomic variant classification systems and nomenclature to accommodate rare variants will be required to adopt sequencing-based pharmacogenomics.

Clinical pharmacogenomic testing has been available since the early 2000s. In recent years, technological advancements have allowed for more cost-effective testing, leading to an increase in the number of laboratories that offer this service.1, 2, 3 The current strategy for most pharmacogenomic assays entails targeted genotyping designed to detect specific variants that have been well characterized for their effect on drug metabolism. The field of pharmacogenomics has quickly expanded in scope and knowledge, and until recently there were few large-scale, coordinated efforts to standardize assays. Therefore, historically there has been significant interlaboratory variability in both the genes tested and the specific variants or alleles included in clinical test design.

To reduce testing variability that might negatively affect patient care, the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), in collaboration with other professional societies, has recommended a minimum list of alleles to be included in clinical testing for pharmacogenes.4, 5, 6, 7 These guidelines ensure that targeted genotyping assays cover the most common clinically relevant alleles. However, most genes that encode for drug-metabolizing enzymes are highly polymorphic, and rare variants are collectively common.8, 9, 10 Thus, testing via targeted genotyping may miss rare but potentially clinically relevant variants.11 This is particularly true among populations that have been historically underrepresented in research and genetic sequencing cohorts.12,13 Therefore, even common variants may be excluded from targeted analyses from some laboratories if they are specific to an underrepresented population.14 A false-negative result attributable to the presence of a variant or allele that was not included in the test design can lead to inappropriate genotype assignment and therapeutic recommendations. Therefore, the limitations of targeted genotyping raise the question of whether a sequencing-based approach to both testing and interpretation would lead to both improved and more inclusive patient care.

Sequencing-based approaches allow for detection of both common and rare variants within the region of interest, providing an assessment of each gene included in a pharmacogenomic test with less bias attributable to test design than a targeted genotyping-based test. In addition, sequencing-based approaches have the advantage of future reanalysis with the most up-to-date information for any variants that were poorly characterized at the time of initial testing. These benefits may improve patient care. Furthermore, sequencing-based approaches have good concordance with chip-based approaches for known pharmacogenomic variants.15 However, in the context of pharmacogenomics, sequencing, particularly by short-read next-generation sequencing (NGS), may not be the most practical approach. The technology is still costly, and the complexity of pharmacogenomic data may require specialized algorithms, particularly for CYP2D6 (eg, Aldy, Astrolable, CNVAR, Hubble, Stargazer).16, 17, 18 In addition, the field of clinical pharmacogenomics lacks standardized nomenclature to describe rare variants in the context of the star allele system (eg, when a rare variant is found along with a group of other variants that comprise a known star allele). Furthermore, variant interpretation guidelines are not designed for pharmacogenomics, complicating interpretation for rare variants.19 The current study aimed to compare an NGS-based testing method with a targeted genotyping approach to determine how frequently genetic variants and haplotypes with potential clinical significance are missed by typical targeted genotyping–based assays.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Study participants from the Right Drug, Right Dose, Right Time: Using Genomic Data to Individualize Treatment (RIGHT 10K) study were included, details of which have been reported previously.20,21 Briefly, 10,074 patients in the Mayo Clinic Biobank participated in a study aimed at understanding the effect of genomic variation on therapeutic outcomes. After exclusion of patients who had undergone liver transplantation or withdrew consent, the final cohort for this study was 10,030 participants. Each RIGHT 10K participant underwent clinical NGS testing for a panel of PGx genes, and the sequencing-based PGx results were deposited into the patients' electronic health record for consideration in clinical care. At study enrollment, written informed consent was also provided to allow access to the participants' pharmacogenetic data and electronic health records in future research. The RIGHT 10K Study was approved by the institutional review board at the Mayo Clinic and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Pharmacogenetic Sequencing

Sequencing was performed by the Baylor College of Medicine's Human Genome Sequencing Center using PGx-seq, the third iteration of a targeted capture sequencing panel that features 77 pharmacogenetic genes first developed by the Pharmacogenomics Research Network.22 This capture includes all exons, splice junctions, upstream and downstream regulatory regions for each gene, as well as probes corresponding to additional sites present on several commercial pharmacogenetic microarray platforms. Analyses for the current study focused on 11 genes with established clinical utility: CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, DPYD, SLCO1B1, TPMT, UGT1A1, and VKORC1. Although the RIGHT 10K Study also evaluated specific HLA-A and HLA-B alleles, these were not included in the current study because these genes were interpreted and reported as targeted genotyping (ie, rather than reporting the specific HLA allele detected, the results were reported as positive or negative for HLA-A∗31:01, HLA-B∗15:02, HLA-B∗57:01, and HLA-B∗58:01).

Sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (San Diego, CA) generating 101-bp paired end reads followed by analysis using the Mercury version 3.2 pipeline.23 The output data were converted to individual FastQ files by Illumina BCL2FASTQ version 1.8.3 software and mapped to the hg19 human genome reference using the Burrow-Wheeler Aligner (specifically, BWA-MEM version 0.7.15).24 The variant calls and annotations were performed using Atlas2 version 1.4.3 (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; https://www.hgsc.bcm.edu/software). The mean quality control metrics of the sequencing data were >70% of reads aligned to target, >99% target bases covered at >20 times, >98% target bases covered at >40 times, and mean coverage of target bases >200 times. Samples were confirmed with a Fluidigm SNP Trace panel to ensure correct sample identification.25

Sequencing Data Interpretation

Genotypes and phenotypes were assigned using look-up tables of common haplotypes created by the Mayo Clinic Personalized Genomics Laboratory. Proprietary software developed at Mayo Clinic (CNVAR version 1.0) was used to generate the CYP2D6 genotype and phenotype using short-read NGS data. This software was developed outside the study described in this article, without use of NIH funding, and is not currently publicly available. CNVAR was validated using a set of 500 samples with known CYP2D6 genotypes based on a combination of targeted genotyping, copy number variation analysis, and Sanger sequencing. The software analyzes the raw sequencing data to identify sequence variants and corresponding variant allele fraction, as well as the read depth for all exons and the promoter region of CYP2D6 and CYP2D7. Statistical methods are applied to determine the best fit for possible genotype solutions. Unexpected variants, including rare variants described in this study, are flagged for manual review. A small number of samples (approximately 1%) with ambiguous CNVAR results were reflexed through the Mayo Clinic CYP2D6 cascade testing, which includes long-range PCR to isolate specific alleles followed by Sanger sequencing, to determine an accurate genotype and phenotype. All variants that were detected and not included in the standard tables were reviewed by laboratory directors with pharmacogenetic experience at Mayo Clinic.

The Pharmacogene Variation Consortium (www.pharmvar.org, last accessed October 8, 2021), TPMT nomenclature database26 (https://liu.se/en/research/tpmt-nomenclature-committee, last accessed October 8, 2021), and UGT1A1 allele nomenclature database (https://www.pharmacogenomics.pha.ulaval.ca, last accessed October 8, 2021) were queried, both as variants were identified and reported and at the time of writing (April 2021), to determine if the variant(s) had been assigned a star allele (for applicable genes). Variants/alleles with unknown function were evaluated using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria for variant interpretation with modifications.19 Variants that were classified as benign or likely benign were not reported, whereas variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) and those expected to affect protein quantity or function were included in clinical reports. Reportable variants without a corresponding star allele were reported using Human Gene Variation Society nomenclature. Nomenclature was developed to report variants found on the background of known star allele(s). Specifically, when the cis/trans status was known, the variant was reported along with the star allele and the word with (eg, ∗2/∗6 with a heterozygous c.307C>T, p.Pro103Ser). When the cis/trans status was unknown, a semicolon was used (eg, ∗2/∗6; a heterozygous c.307C>T, p.Pro103Ser was detected).

Genotypes were used to predict phenotypes, including poor (ie, no to very little enzyme activity), intermediate (ie, typically approximately half of the enzyme activity of a patient with two wild-type alleles), normal, rapid, or ultrarapid (ie, increased enzyme activity) metabolizer based on the clinical methods used in the Mayo Clinic Personalized Genomics Laboratory. When a VUS was reported, a phenotype range was provided (eg, one nonfunctional allele and one VUS led to a report of poor to intermediate metabolizer).

Comparison of Targeted Genotyping versus NGS Approach

An in silico representative targeted genotyping panel was created by reviewing the alleles included by clinical laboratories listed in the Genetic Testing Registry (GTR; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr, last accessed April 6, 2020) as of April 6, 2020 (Table 1). This process included review of 30 College of American Pathologists–accredited, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories based in the United States. Information regarding the variants included in targeted genotyping was identified for 23 of the 30 laboratories. Variants were included in the in silico panel if at least 50% of these laboratories’ current clinical tests contained the variant (Supplemental Table S1). This analysis was performed independently for each individual gene, and the percentage of laboratories that included the variant was calculated by dividing the number of laboratories that included the variant by the number of laboratories that tested that gene.

Table 1.

Summary of in Silico Panel and Nonpanel Variants Identified by Sequencing

| Gene | In silico targeted panel alleles | Participants with nonpanel variants, n (%) | Nonpanel variants/alleles identified, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | ∗1C, ∗1D, ∗1E, ∗1F, ∗1K | 203 (2.0) | 74 |

| CYP2C19 | ∗2, ∗3, ∗4, ∗5, ∗6, ∗7, ∗8, ∗9, ∗10, ∗17 | 121 (1.2) | 63 |

| CYP2C9 | ∗2, ∗3, ∗4, ∗5, ∗6, ∗8, ∗11 | 205 (2.0) | 65 |

| CYP2D6 | ∗2, ∗3, ∗4, ∗5 (deletion), ∗6, ∗7, ∗8, ∗9, ∗10, ∗11, ∗12, ∗14, ∗15, ∗17, ∗29, ∗35, ∗41, ∗114, duplications | 350 (3.5) | 103 |

| CYP3A4 | ∗22 | 127 (1.3) | 61 |

| CYP3A5 | ∗3, ∗6, ∗7 | 11 (0.1) | 11 |

| DPYD | c.1905+1G>A (∗2A); c.1679T>G (∗13); c.2846A>T (rs67376798) | 630 (6.3) | 112 |

| SLCO1B1 | ∗5 | 1292 (12.9) | 68 |

| TPMT | ∗2, ∗3A, ∗3B, ∗3C, ∗4 | 30 (0.3) | 14 |

| UGT1A1 | ∗28 (TA7), ∗36 (TA5) | 116 (1.2) | 35 |

| VKORC1 | c.-1639G>A | 96 (1.0) | 18 |

This representative in silico targeted genotyping panel was then retrospectively applied to the full sequencing data generated in the RIGHT 10K Study, followed by comparison of results and phenotype interpretation between sequencing and targeted genotyping approaches. In addition, sequencing results were evaluated compared with the AMP tier 1 and tier 2 alleles for applicable genes (Table 2). To ensure clinical relevance of the comparison, only clinically reported sequencing variants were included (ie, known pathogenic variants, likely pathogenic variants, and VUSs). Alleles predicted to have normal activity, as well as those unlikely to further affect function or the patient's phenotype, were excluded (eg, rare variant on background of null allele, CYP2D6 hybrid alleles, a frameshift variant in a patient who was considered a poor metabolizer based on other variants present). The final data set of variants that would be missed by the in silico panel or by a panel that included the AMP-recommended alleles represents only cases in which a patient result would be affected.

Table 2.

Participants with Variants That Would Not Be Detected by Laboratories That Are Testing the Association for Molecular Pathology Tier 1 and Tier 2 Alleles

| Gene | Alleles included | Participants with a variant not in tier 1, n (%) | Participants with a variant not in tier 1 or tier 2, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C96 | Tier 1: ∗2, ∗3, ∗5, ∗6, ∗8, ∗11 | 205 (2.0) | 131 (1.3) |

| Tier 2: ∗12, ∗13, ∗15 | |||

| CYP2C197 | Tier 1: ∗2, ∗3, ∗17 | 207 (2.0) | 115 (1.1) |

| Tier 2: ∗4A, ∗4B, ∗5, ∗6, ∗7, ∗8, ∗9, ∗10, ∗35 | |||

| CYP2D64 | Tier 1: ∗2, ∗3, ∗4, ∗5, ∗6, ∗9, ∗10, ∗17, ∗29, ∗41, xN | 459 (4.6) | 302 (3.0) |

| Tier 2: ∗7, ∗8, ∗12, ∗14, ∗15, ∗21, ∗31, ∗40, ∗42, ∗49, ∗56, ∗59, hybrid alleles | |||

| VKORC15 | Tier 1: c.-1639G>A | 96 (1.0) | 78 (0.8) |

| Tier 2: c.106G>T, c.196G>A |

Results

The alleles included in the in silico panel are listed in Table 1, and details regarding the number of laboratories in the GTR that test each allele are included in Supplemental Table S1. Similar to the findings of other studies, significant interlaboratory variability was observed in alleles included in clinical tests.27,28 The in silico panel included all the tier 1 must-test alleles for CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and VKORC1 based on the recommendations of the AMP Pharmacogenetics Working Group.4, 5, 6, 7 However, several CYP2C9 alleles were not tested by all laboratories. Specifically, CYP2C9∗5, ∗6, ∗8, and ∗11 were included in the clinical tests of 87.5%, 81.3%, 62.5%, and 68.8% of the sampled laboratories, respectively (Supplemental Table S1). This finding is particularly important given that these alleles are more common in populations of African descent than those of European descent. Similarly, CYP2D6 tier 1 alleles ∗3, ∗5/copy number variation, ∗9, and ∗29 were each included in 93.3% of laboratories' tests. The other tier 1 alleles were included in all laboratory tests sampled. In addition, the in silico panel included all CYP2C19 tier 2 alleles except ∗35 and included the ∗7, ∗8, ∗12, ∗14, and ∗15 CYP2D6 tier 2 alleles. The CYP2C9 and VKORC1 tier 2 alleles were not included, reflecting their presence in <50% of the laboratory tests listed in the GTR.

In the cohort, 2780 of 10,030 participants (28%) had a potentially clinically significant variant or allele identified by sequencing that would not have been detected in most current clinical targeted genotyping panels. In a portion of these participants, more than one gene was found with a rare and potentially relevant variant not featured in most targeted assays (2 genes: n = 344, 3 genes: n = 27, 5 genes: n = 1). The number of participants found by sequencing to have potentially clinically relevant variants not included in the in silico panel are listed in Table 1. In addition, if all laboratories adopted the AMP guidelines for CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and VKORC1, potentially clinically relevant variants would continue to be missed (Table 2). Of note, when comparing the in silico panel with the AMP tier 1, the same (CYP2C9 and VKORC1) or more (CYP2C19 and CYP2D6) participants with a potentially significant variant would not have been identified. However, if the tier 2 alleles were also clinically implemented, fewer participants would have a variant that was not detected.

All genes studied had variants missed by a targeted genotyping–based approach that are of potential clinical significance. Potentially significant variants/alleles that could result in misclassification of the phenotype were identified most frequently in SLCO1B1 (n = 1292), DPYD (n = 630), and CYP2D6 (n = 350). The genes with the lowest number of participants with clinically significant variants missed were TPMT (n = 30) and CYP3A5 (n = 11).

The number of individual variants or alleles that were not detected also varied by gene. DPYD (n = 112) and CYP2D6 (n = 103) had the largest number of unique variants missed by targeted genotyping, whereas the fewest unique variants were missed in CYP3A5 (n = 11), and TPMT (n = 14) (Table 1). There were several variants that were found in many participants (Table 3).

Table 3.

Commonly Encountered Nonpanel Variants in This Predominantly White Population and Their Functional Impact

| Gene | Variant/allele | MAF, % | Functional impact | Laboratories testing variant, n/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CYP1A2 (NM_000761.4) |

c.841C>T/p.Arg281Trp | 0.184 | VUS | 0/10 |

| c.1291C>T (∗6)/p.Arg431Trp | 0.105 | No expression29 | 4/10 | |

|

CYP2C19 (NM_000769.4) |

c.527A>G/p.Arg186Cys | 0.050 | VUS | 0/16 |

| [c.332-23A>G; c.991A>G] (∗35)/[p.?;p.Ile331Val] | 0.035 | No function | 2/16 | |

|

CYP2C9 (NM_000771.3) |

c.1324G>A/p.Gly442Ser | 0.060 | VUS | 0/16 |

| c.1465C>T (∗12)/p.Pro489Ser | 0.379 | Decreased function | 2/16 | |

|

CYP2D6 (NM_000106.6) |

c.82C>T (∗22)/p.Arg28Cys | 0.229 | VUS | 0/15 |

| [c.19G>A;c.451C>G; c.886C>T;c.1457G>C] (∗28)/[p.Val7Met;p.Gln151Glu; p.Arg296Cys;p.Ser486Thr] | 0.150 | VUS | 0/15 | |

| [c.886C>T;c.975G>A; c.1457G>C] (∗59)/[p.Arg296Cys;p.Pro325 = ;p.Ser486Thr] (p.Pro325 = results in splice defect) | 0.060 | Decreased function | 2/15 | |

|

CYP3A4 (NM_017460.5) |

c.389G>A (∗8)/p.Arg130Gln | 0.080 | Decreased function30 | 1/14 |

| c.1461dup (∗20)/p.Pro488Thrfs∗7 | 0.060 | No function | 1/14 | |

|

DPYD (NM_000110.4) |

c.1129-5923C>G/p.? (HapB3) | 2.433 | Decreased function | 1/11 |

|

SLCO1B1 (NM_006446.4) |

c.-910G>A (∗21)/p.? | 5.937 | Possibly reduced transport,31 found with c.521 as ∗17 in >91 participants | 3/11 |

| c.1738C>T/p.Arg580∗ | 0.075 | No function, all found on ∗5 background | 0/11 | |

|

TPMT (NM_000367.4) |

c.356A>C (∗9)/p.Lys119Thr | 0.030 | VUS32 | 0/14 |

| c.374C>T (∗12)/p.Ser125Leu | 0.040 | Decreased function32 | 1/14 | |

|

UGT1A1 (NM_000463.2) |

c.211G>A (∗6)/p.Gly71Arg | 0.294 | Decreased function33 | 3/9 |

| c.748T>C/p.Ser250Pro | 0.060 | VUS | 0/9 | |

|

VKORC1 (NM_024006.5) |

c.106G>T/p.Asp36Tyr | 0.085 | Warfarin resistance34 | 1/13 |

| c.358C>T/p.Leu120Leu | 0.229 | Possible warfarin resistance35 | 1/13 |

The variants are described using Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature, along with the star allele (when applicable). The expected functional impact is provided for each variant from PharmVar, unless the variant was of uncertain significance or a reference is provided. Finally, the number of laboratories represented in the Genetic Testing Registry that test for the variant is indicated. With greater population diversity, a larger number and different subsets of nonpanel variants would be expected. The cDNA numbering for each gene is based on the reference transcript sequence indicated by the accession number (NM) provided in parentheses for each gene. Reference transcript sequences are available from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (last accessed November 8, 2021). MAF, minor allele frequency; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

DPYD c.1129-5923C>G, which was only included in the test of 1 of 11 laboratories (9.1%), was found in 480 participants, including eight homozygotes for a minor allele frequency (MAF) in the patient cohort of 2.43%. UGT1A1∗6 was included in the test design by 3 of 9 laboratories (33.3%) and was identified in 55 participants, including four homozygotes for an MAF of 0.30% in the patient cohort. This variant accounted for 47.4% of the UGT1A1 variants not detected by genotyping. CYP2C9∗12 was identified in 76 participants (cohort MAF = 0.38%). This allele was not in the in silico panel because it was only included in the test design for 2 of 16 laboratories (12.5%) with available data in the GTR. A list of the most common variants identified in each gene as well as the number of laboratories that include that allele in their targeted genotyping assay are provided in Table 3.

Discussion

Pharmacogenetic results were compared for a cohort of participants generated using both a sequencing-based approach and a targeted genotyping–based approach.21 The results indicated that 28% of participants had at least one potentially clinically relevant variant/allele identified by sequencing that would not have been detected in a targeted genotyping panel based on the in silico panel composed of variants currently included by at least 50% of clinical laboratories listed in the GTR. Although many of these variants are VUSs, this finding is concerning considering the RIGHT 10K Study participants are predominantly of European descent, on which targeted genotyping assays were historically based, and suggests not only that a subset of clinically actionable variants are going undetected but also that individuals have many variants for which the function is not yet known. However, this is not entirely surprising, given that recent reports have suggested that individual genomes harbor >100 single-nucleotide variants in pharmacogenomic loci and that >90% of these single-nucleotide variants are rare (MAF <1%).36 Higher rates of undetected variants/alleles with potential clinical significance may be expected in other populations, particularly those who have not historically been included in large-scale sequencing initiatives.

A sequencing-based approach has several advantages. It is a more inclusive testing strategy to detect common and rare variants across race/ethnic groups and may decrease interlaboratory variability of variants detected. Although this approach may yield more VUSs, this may also be an advantage, given the possibility of reanalysis with new scientific information. Pharmacogenetic research is ongoing. Newer techniques for high-throughput functional studies, such as deep mutational scanning, are now available and may contribute to variant classification.37,38 Insurance coverage for pharmacogenetic testing remains limited, and often when testing is considered medically necessary, testing may only be covered once. Although a particular VUS may not offer clinical guidance at the time of detection, the possibility remains that clinical significance will become established with time and, if appropriate, incorporated into guidelines. In contrast, targeted genotyping panels with only established variants will not detect VUSs; therefore, the potential for reanalysis in the setting of new pharmacogenetic information is limited. Furthermore, NGS-based testing, including exomes and genomes, for a variety of indications has become more commonly used. When the capture includes pharmacogenes, it may be feasible to generate a pharmacogenetic interpretation alongside other testing. However, the challenges and cost associated with NGS testing are not without mention. Similar to targeted genotyping, a sequencing panel can only provide information on the genes and regions included in the tests. Pharmacogenes are highly polymorphic because they may have undergone very minimal or no selection against variation, in contrast to most disease-associated genes for which the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics variant interpretation guidelines were constructed. This creates challenges for variant interpretation. For instance, several criteria typically assessed, including variant MAF and evolutionary conservation, may be of limited value. Therefore, sequencing-based pharmacogenetic testing is likely to yield many VUSs for which there is no established translation to phenotype.

The likelihood of uncovering more than one clinically relevant variant also means that accurate phenotype prediction would require determining cis/trans status (phase), which is not always possible with short-read NGS technology. Furthermore, there is no standardized nomenclature for reporting genotypes in the context of identification of a rare variant on the background of known star alleles traditionally used. In the research setting, when a new allele is identified, the laboratory can contact PharmVar and a new star allele may be created; however, clinical reporting requires an immediate nomenclature solution. Pharmacogenetic nomenclature is already considerably complex, with highly polymorphic pharmacogenes, such as CYP2D6, requiring specialized and sometimes proprietary algorithms to accurately call genotypes and infer phenotypes. The routine addition of VUSs and rare alleles with limited data may further complicate matters. However, having a system to classify pharmacogenetic variants and consistently convey both the genotype and phenotype information along with any uncertainty present would make this feasible for both health care professionals and laboratories.

The results of this study demonstrate improved clinical yield with sequencing compared with standard targeted genotyping in pharmacogenomic testing. However, for the reasons outlined above, sequencing may not yet be feasible or practical for many clinical testing laboratories. In such cases, certain considerations may improve targeted test design. Sequencing yielded minimal increased benefit for several genes. For example, UGT1A1 and SLCO1B1 each had a single variant that explained most of the false-negative results [∗6 in UGT1A1 (55 of 116 missed variants) and ∗21 in SLCO1B1 (1191 of 1292 missed variants)]. The UGT1A1∗6 variant is particularly common in populations of East Asian descent (MAF = 15.3%) compared with those of non-Finnish European descent (0.20%).39 Therefore, simply adding this variant to targeted genotyping panels is a reasonable approach to increasing sensitivity. The clinical effect of the SLCO1B1∗21 allele is less well established, although the defining variant, c.-910G>A (NM_006446.4), may affect the efficacy of pravastatin.31,40 Additional studies to understand the clinical significance of this variant on the many medications that are transported by OATP1B1, which is encoded by SLCO1B1, will be important, especially given the frequency of this variant. Of note, this variant may not be present in an NGS capture designed for nonpharmacogenomic purposes because of its position far upstream of SLCO1B1. Furthermore, limited variation was observed within TPMT, which is highly conserved and has no known natural substrate. In addition, loss of function alleles in CYP3A5 are common in individuals of European descent, and additional variants uncovered in individuals already considered poor metabolizers were not expected to alter the phenotype further. Therefore, a transition to sequencing-based testing may have a smaller effect on these genes.

In contrast, DPYD and CYP2D6 had a high number of unique potentially clinically relevant variants that would have been missed by standard targeted genotyping. Approximately 6% of the patient cohort (n = 631) carried a DPYD variant missed by the in silico targeted genotyping panel. Of note, the deeply intronic splice site variant, c.1129-5923C>G, was identified in the patient cohort at an MAF of 2.4%, including eight homozygotes. The c.1129–5923C>G is the functional variant within the hapB3 genotype and a known contributor to severe fluorouracil toxicity in white populations.41,42 Although adding the DPYD c.1129-5923C>G variant would improve targeted genotyping, there were >100 additional variants each found in one or a few patients. Similarly, many variants in CYP2D6 were found in a small number of individuals. A total of 350 individuals (3.5%) in the patient cohort had CYP2D6 variants that would have been missed by targeted genotyping. Although there were several recurrent variants, such as ∗22, ∗28, and ∗59, which affected 45, 29, and 12 participants, respectively, 76 of the 103 CYP2D6 variants/alleles were only identified in one individual. Because CYP2D6 is highly polymorphic, patients would benefit from sequencing over targeted testing; however, specialized algorithms are often necessary for accurate CYP2D6 genotyping by NGS because of the high homology with CYP2D7. Of note, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and SLCO1B1 also had many variants found in only one or a few individuals, suggesting that sequencing would be a more sensitive approach than genotyping; however, in the case of SLCO1B1 in particular, the bulk of the variants are VUSs, and additional research is needed to understand the significance of variants identified.

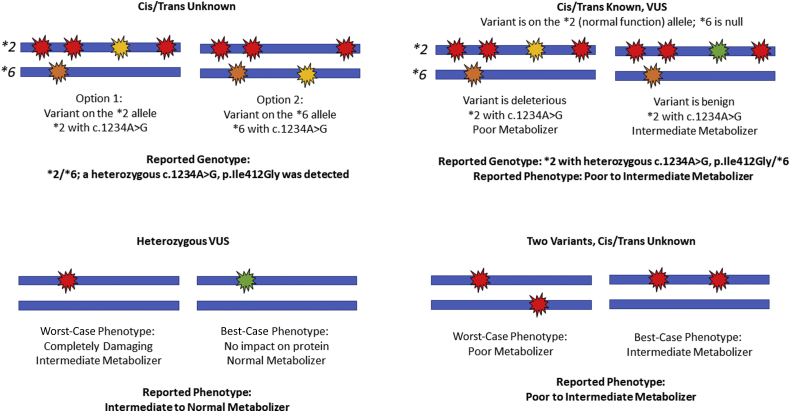

To overcome several challenges of NGS reporting, a novel system of nomenclature was developed and tested for this study (Figure 1). This system may overcome some of the barriers to use of a sequencing-based approach. Specifically, terms were developed to report the rare variants/alleles that do not have a corresponding star name. When the cis/trans status was known, the star allele is listed corresponding to the other variants present (if any) in cis followed by the word “with” along with the additional variant(s) described using the Human Gene Variation Society nomenclature. When the cis/trans status was unknown, the diplotype is listed, followed by a semicolon and the additional variant(s) identified. To overcome ambiguous phenotypes because of VUS and unknown cis/trans status, a phenotype range was used. For example, if the variant is a VUS or the cis/trans configuration with another reportable variant is unknown, a worst-case phenotype and a best-case phenotype were used to report a phenotype range (eg, poor to intermediate metabolizer). After explaining this system, end users, including pharmacists, thought that the nomenclature was understandable. Therefore, this may be a viable solution for clinical laboratories, which could be adopted when routine assays are converted from targeted genotyping to NGS.

Figure 1.

Example genotype and phenotype nomenclature for challenging scenarios. Each panel depicts two alleles (blue bars) with variants (red, yellow, orange, or green markers). In each case, the configuration and/or clinical significance of the variants is unknown, resulting in two possible genotypes and/or phenotypes. The asterisk denotes a star allele (haplotype). VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

In conclusion, the limited scope of targeted genotyping in pharmacogenetics means clinically relevant variants are often missed, especially in historically understudied populations. A sequencing-based approach offers improved variant detection and therefore more accurate patient metabolizer phenotype classification. However, many challenges remain for NGS implementation, including increased cost, technical aspects, and interpretation and reporting of novel variants. Therefore, expansion of the scope of targeted assays may be a more practical short-term solution for some clinical testing laboratories. In the long term, as sequencing data become more widely available, it will be important to have systems in place to analyze and report pharmacogenetic information generated by sequencing-based approaches.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Personalized Genomics Laboratory at Mayo Clinic for performing CYP2D6 follow-up testing and variant confirmation as needed, as well as Richard Gibbs, Donna Muzny, Xiang Qin, and the staff at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center, and the Center for Individualized Medicine at the Mayo Clinic for their roles in the RIGHT 10K Study.

Footnotes

Supported by the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, and NIH grants U19 GM61388 (Pharmacogenomics Research Network) (S.E.S., L.W., and R.M.W.), R01 GM28157 (L.W. and R.M.W.), U01 HG005137 (R.M.W.), R01 GM125633 (L.W.), R01 AG034676 (Rochester Epidemiology Project), U01 HG06379 and U01 HG06379 (Electronic Medical Record and Genomics Network) (S.J.B.), and T32 HL007111 (G.S.L.).

Disclosures: J.L.B., L.W., R.M.W., and the Mayo Clinic have stock ownership and licensed intellectual property to OneOme LLC and receive royalties. J.L.B. and the Mayo Clinic have licensed intellectual property to AssureX Health, and J.L.B. declares stock and royalties from AssureX Health. Mayo Clinic Laboratories offers pharmacogenomic testing.

Current address of J.L.L., Division of Human Genetics, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH; of G.S.L., Premier Applied Sciences, Premier Inc., Charlotte, NC.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2021.11.008.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Johnson J.A. Pharmacogenetics in clinical practice: how far have we come and where are we going? Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:835–843. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahawi S., Naik H., Blake K.V., Owusu Obeng A., Wasserman R.M., Seki Y., Funanage V.L., Oishi K., Scott S.A. Knowledge and attitudes on pharmacogenetics among pediatricians. J Hum Genet. 2020;65:437–444. doi: 10.1038/s10038-020-0723-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer A.M., Caraballo P.J. The challenges of implementing pharmacogenomic testing in the clinic. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17:567–577. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2017.1385395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratt V.M., Cavallari L.H., Del Tredici A.L., Gaedigk A., Hachad H., Ji Y., Kalman L.V., Ly R.C., Moyer A.M., Scott S.A., van Schaik R.H.N., Whirl-Carrillo M., Weck K.E. Recommendations for clinical CYP2D6 genotyping allele selection: a joint consensus recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, College of American Pathologists, Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group of the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association, and European Society for Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Therapy. J Mol Diagn. 2021;23:1047–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2021.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratt V.M., Cavallari L.H., Del Tredici A.L., Hachad H., Ji Y., Kalman L.V., Ly R.C., Moyer A.M., Scott S.A., Whirl-Carrillo M., Weck K.E. Recommendations for clinical warfarin genotyping allele selection: a report of the Association for Molecular Pathology and the College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn. 2020;22:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2020.04.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt V.M., Cavallari L.H., Del Tredici A.L., Hachad H., Ji Y., Moyer A.M., Scott S.A., Whirl-Carrillo M., Weck K.E. Recommendations for clinical CYP2C9 genotyping allele selection: a joint recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn. 2019;21:746–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratt V.M., Del Tredici A.L., Hachad H., Ji Y., Kalman L.V., Scott S.A., Weck K.E. Recommendations for clinical CYP2C19 genotyping allele selection: a report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2018;20:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drogemoller B.I., Wright G.E., Warnich L. Considerations for rare variants in drug metabolism genes and the clinical implications. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10:873–884. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2014.903239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozyra M., Ingelman-Sundberg M., Lauschke V.M. Rare genetic variants in cellular transporters, metabolic enzymes, and nuclear receptors can be important determinants of interindividual differences in drug response. Genet Med. 2017;19:20–29. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinshilboum R., Wang L. Pharmacogenomics: bench to bedside. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:739–748. doi: 10.1038/nrd1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizzi C., Peters B., Mitropoulou C., Mitropoulos K., Katsila T., Agarwal M.R., van Schaik R.H., Drmanac R., Borg J., Patrinos G.P. Personalized pharmacogenomics profiling using whole-genome sequencing. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1223–1234. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solus J.F., Arietta B.J., Harris J.R., Sexton D.P., Steward J.Q., McMunn C., Ihrie P., Mehall J.M., Edwards T.L., Dawson E.P. Genetic variation in eleven phase I drug metabolism genes in an ethnically diverse population. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:895–931. doi: 10.1517/14622416.5.7.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mapes B., El Charif O., Al-Sawwaf S., Dolan M.E. Genome-wide association studies of chemotherapeutic toxicities: genomics of inequality. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:4010–4019. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y., Ingelman-Sundberg M., Lauschke V.M. Worldwide distribution of cytochrome P450 alleles: a meta-analysis of population-scale sequencing projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102:688–700. doi: 10.1002/cpt.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng D., Hong C.S., Singh L.N., Johnston J.J., Mullikin J.C., Biesecker L.G. Assessing the capability of massively parallel sequencing for opportunistic pharmacogenetic screening. Genet Med. 2017;19:357–361. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Schaik R.H.N., Muller D.J., Serretti A., Ingelman-Sundberg M. Pharmacogenetics in psychiatry: an update on clinical usability. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:575540. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.575540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S.B., Wheeler M.M., Patterson K., McGee S., Dalton R., Woodahl E.L., Gaedigk A., Thummel K.E., Nickerson D.A. Stargazer: a software tool for calling star alleles from next-generation sequencing data using CYP2D6 as a model. Genet Med. 2019;21:361–372. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Twesigomwe D., Wright G.E.B., Drogemoller B.I., da Rocha J., Lombard Z., Hazelhurst S. A systematic comparison of pharmacogene star allele calling bioinformatics algorithms: a focus on CYP2D6 genotyping. NPJ Genom Med. 2020;5:30. doi: 10.1038/s41525-020-0135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., Voelkerding K., Rehm H.L., Committee A.L.Q.A. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bielinski S.J., Olson J.E., Pathak J., Weinshilboum R.M., Wang L., Lyke K.J., Ryu E., Targonski P.V., Van Norstrand M.D., Hathcock M.A., Takahashi P.Y., McCormick J.B., Johnson K.J., Maschke K.J., Rohrer Vitek C.R., Ellingson M.S., Wieben E.D., Farrugia G., Morrisette J.A., Kruckeberg K.J., Bruflat J.K., Peterson L.M., Blommel J.H., Skierka J.M., Ferber M.J., Black J.L., Baudhuin L.M., Klee E.W., Ross J.L., Veldhuizen T.L., Schultz C.G., Caraballo P.J., Freimuth R.R., Chute C.G., Kullo I.J. Preemptive genotyping for personalized medicine: design of the right drug, right dose, right time-using genomic data to individualize treatment protocol. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bielinski S.J., St Sauver J.L., Olson J.E., Larson N.B., Black J.L., Scherer S.E., et al. Cohort profile: the Right Drug, Right Dose, Right Time: Using Genomic Data to Individualize Treatment Protocol (RIGHT Protocol) Int J Epidemiol. 2019;49:23–24k. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon A.S., Fulton R.S., Qin X., Mardis E.R., Nickerson D.A., Scherer S. PGRNseq: a targeted capture sequencing panel for pharmacogenetic research and implementation. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2016;26:161–168. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid J.G., Carroll A., Veeraraghavan N., Dahdouli M., Sundquist A., English A., Bainbridge M., White S., Salerno W., Buhay C., Yu F., Muzny D., Daly R., Duyk G., Gibbs R.A., Boerwinkle E. Launching genomics into the cloud: deployment of Mercury, a next generation sequence analysis pipeline. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang-Chu M.M., Yu M., Haverty P.M., Koeman J., Ziegle J., Lee M., Bourgon R., Neve R.M. Human biosample authentication using the high-throughput, cost-effective SNPtrace(TM) system. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appell M.L., Berg J., Duley J., Evans W.E., Kennedy M.A., Lennard L., Marinaki T., McLeod H.L., Relling M.V., Schaeffeler E., Schwab M., Weinshilboum R., Yeoh A.E., McDonagh E.M., Hebert J.M., Klein T.E., Coulthard S.A. Nomenclature for alleles of the thiopurine methyltransferase gene. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2013;23:242–248. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835f1cc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalman L.V., Agundez J., Appell M.L., Black J.L., Bell G.C., Boukouvala S., et al. Pharmacogenetic allele nomenclature: International workgroup recommendations for test result reporting. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:172–185. doi: 10.1002/cpt.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moyer A.M., Rohrer Vitek C.R., Giri J., Caraballo P.J. Challenges in ordering and interpreting pharmacogenomic tests in clinical practice. Am J Med. 2017;130:1342–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou H., Josephy P.D., Kim D., Guengerich F.P. Functional characterization of four allelic variants of human cytochrome P450 1A2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;422:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X.Y., Hu X.X., Wang C.C., Lu X.R., Chen Z., Liu Q., Hu G.X., Cai J.P. Enzymatic activities of CYP3A4 allelic variants on quinine 3-hydroxylation in vitro. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:591. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niemi M., Schaeffeler E., Lang T., Fromm M.F., Neuvonen M., Kyrklund C., Backman J.T., Kerb R., Schwab M., Neuvonen P.J., Eichelbaum M., Kivisto K.T. High plasma pravastatin concentrations are associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes of organic anion transporting polypeptide-C (OATP-C, SLCO1B1) Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:429–440. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000114750.08559.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L., Pelleymounter L., Weinshilboum R., Johnson J.A., Hebert J.M., Altman R.B., Klein T.E. Very important pharmacogene summary: thiopurine S-methyltransferase. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:401–405. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283352860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbarino J.M., Haidar C.E., Klein T.E., Altman R.B. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for UGT1A1. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014;24:177–183. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahin M.H., Cavallari L.H., Perera M.A., Khalifa S.I., Misher A., Langaee T., Patel S., Perry K., Meltzer D.O., McLeod H.L., Johnson J.A. VKORC1 Asp36Tyr geographic distribution and its impact on warfarin dose requirements in Egyptians. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109:1045–1050. doi: 10.1160/TH12-10-0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell C., Gregersen N., Krause A. Novel CYP2C9 and VKORC1 gene variants associated with warfarin dosage variability in the South African black population. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:953–963. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauschke V.M., Ingelman-Sundberg M. Requirements for comprehensive pharmacogenetic genotyping platforms. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17:917–924. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2016-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L., Sarangi V., Ho M.F., Moon I., Kalari K.R., Wang L., Weinshilboum R.M. SLCO1B1: application and limitations of deep mutational scanning for genomic missense variant function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2021;49:395–404. doi: 10.1124/dmd.120.000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L., Sarangi V., Moon I., Yu J., Liu D., Devarajan S., Reid J.M., Kalari K.R., Wang L., Weinshilboum R. CYP2C9 and CYP2C19: deep mutational scanning and functional characterization of genomic missense variants. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:727–742. doi: 10.1111/cts.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alfoldi J., Wang Q., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niemi M., Neuvonen P.J., Hofmann U., Backman J.T., Schwab M., Lutjohann D., von Bergmann K., Eichelbaum M., Kivisto K.T. Acute effects of pravastatin on cholesterol synthesis are associated with SLCO1B1 (encoding OATP1B1) haplotype ∗17. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:303–309. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Froehlich T.K., Amstutz U., Aebi S., Joerger M., Largiader C.R. Clinical importance of risk variants in the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene for the prediction of early-onset fluoropyrimidine toxicity. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:730–739. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meulendijks D., Henricks L.M., van Kuilenburg A.B., Jacobs B.A., Aliev A., Rozeman L., Meijer J., Beijnen J.H., de Graaf H., Cats A., Schellens J.H. Patients homozygous f or DPYD c.1129-5923C>G/haplotype B3 have partial DPD deficiency and require a dose reduction when treated with fluoropyrimidines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:875–880. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.