Defects in tubulin beta 2A class IIa (TUBB2A) are associated with a range of complex cerebral cortex dysplasias.1 Despite several studies reporting NM_001069.3:c.743C>T p.(Ala248Val) as a recurrent pathogenic mutation,1 2 it is listed in ClinVar with conflicting interpretations. To resolve these inconsistencies, we scanned data from the 100,000 Genomes Project3 (100KGP) and identified 58 individuals where p.(Ala248Val) had been called. Read alignment analysis suggested that the variant was genuine in 5/58 individuals, all of whom had a primary neurodevelopmental phenotype. In the remaining cases which spanned non-specific disease phenotypes, low allelic ratios (1%–19%) suggest recurrent mismapping artefacts.

Alpha and beta tubulins form heterodimers that polymerise to form microtubules, dynamic components of the cytoskeleton that play an important role in cell division, migration and intracellular transport. Variants in several tubulin genes are associated with a variety of cortical brain malformation phenotypes, including lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, microlissencephaly and simplified gyration, collectively termed ‘tubulinopathies’.4 5 A recently described tubulinopathy involving TUBB2A (MIM #615763) has been associated with brain phenotypes ranging from a normal cortex to extensive dysgyria.2 One particular TUBB2A variant, p.(Ala248Val), has been reported in several studies, in most cases arising de novo.1 2 6–8 Additional unpublished clinical cases also report a de novo origin (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/127101).

Multiple occurrences of the same de novo mutation in patients with overlapping phenotypes would typically provide strong evidence supporting pathogenicity. However, on closer inspection, p.(Ala248Val) becomes harder to interpret, particularly when applying the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) population allele frequency (AF) criteria PM2/BS1.9 The AF in gnomAD v2.1.1 is 8/237 044 in exomes and 79/15 882 in genomes, an unexpected skew for a coding variant. In gnomAD v3.1, the global AF of 400/111 804 rises to 342/24 540 (1.4%) in Africans, well above the normal threshold for a highly penetrant autosomal–dominant condition.

The p.(Ala248Val) variant fails quality control filters in the gnomAD genome datasets and is only visible when the ‘filtered variants’ checkbox is selected. In contrast, it is a PASS variant in the exome subset of gnomAD v2.1.1. This inconsistent AF data likely explains the conflicting interpretations in ClinVar—currently one benign, one likely benign, two likely pathogenic and two pathogenic assessments. This degree of conflict is unusual, as diagnostic laboratories apply ACMG guidelines conservatively and typically report variants as being of uncertain significance when doubt arises.

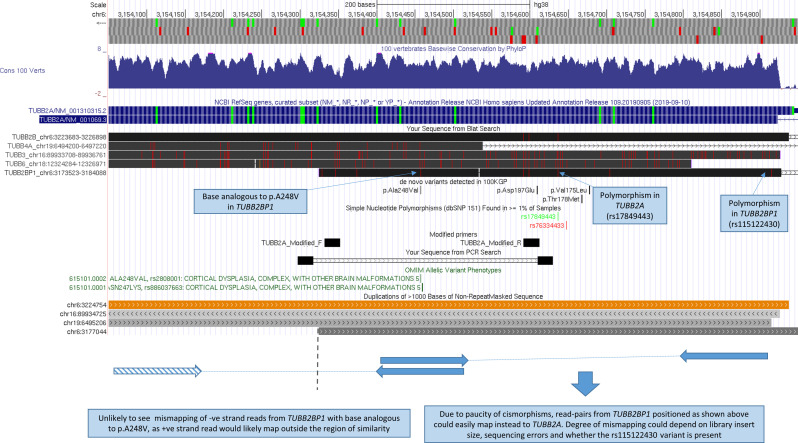

Segmental duplications are known to result in reads with low mapping quality on short-read sequencing, and this can cause mismapping artefacts. Indeed, several regions share similarity with TUBB2A. Although the highest identity is with TUBB2B, other beta tubulin genes (TUBB3/TUBB4A/TUBB6) and a pseudogene (TUBB2BP1) share >90% identity with TUBB2A exon 4 (online supplemental table S1). Notably, TUBB2BP1 contains the analogous base to p.(Ala248Val) in TUBB2A, and this ‘cismorphism’ is in a region relatively depleted for other cismorphisms (figure 1). Thus, we speculate that mismapping of reads from TUBB2BP1 may result in p.(Ala248Val) being called in TUBB2A as an artefact and thus the apparently high AF in gnomAD.

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp001.xlsx (13.5KB, xlsx)

Figure 1.

Relative positions of segmental duplications and hypothesis for strand bias associated with NC_000006.12:g.3154458G>A, p.(Ala248Val). Customised UCSC genome browser session highlighting the positions of segmental duplications showing at least 90% identity (interactive version at: https://genome.ucsc.edu/s/AlistairP/TUBB2A_v5). Region shown corresponds to a 900 bp section of exon 4. The RefSeq annotation corresponding to the canonical TUBB2A isoform is highlighted. The positions of primers used in the Cushion et al study are indicated by the in silico PCR track—the lack of cismorphisms at these sites suggests that TUBB2A and TUBB2B would both be amplified with an equal efficiency. The position of a modified reverse primer which contains mismatches with TUBB2B at the 3′ end is indicated. The position of the base in TUBB2BP1 that is analogous to p.(Ala248Val) is labelled. Cismorphisms at sites which are also polymorphic in TUBB2A or TUBB2BP1 are also labelled. Other de novo variants detected in 100KGP are indicated, although p.(Val49Met) and p.(Arg391His) are not shown as they lie outside the region shown. The schematic diagram below the UCSC session indicates relative positions of hypothetically mismapped read pairs from TUBB2BP1 (which lies 23 kb proximal to TUBB2A), which could explain the strand-bias observed. Negative strand reads from TUBB2BP1 that harbour the base analogous to p.(Ala248Val) are unlikely to mismap to TUBB2A as the corresponding +ve strand paired read then would lie outside the region of similarity. 100KGP, 100,000 Genomes Project; TUBB2A, beta-tubulin isotype 2A.

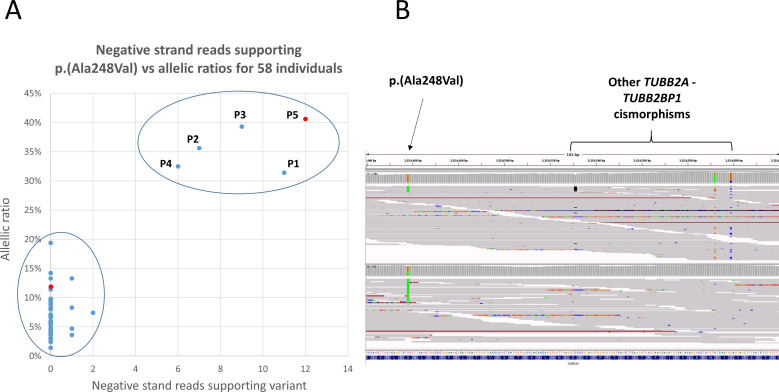

Searching data from 78 195 individuals sequenced as part of the 100KGP (online supplemental material, Methods section) uncovered 58 subjects apparently heterozygous for p.(Ala248Val). On reviewing read alignment statistics, two distinct clusters were seen. In 5/58 individuals, the p.(Ala248Val) variant appeared with allelic ratios of 31%–41%, supported by multiple reads across both strands. In contrast, for the remaining 53 individuals, the variant was observed at lower allelic fractions (1%–19%), almost exclusively on positive strand reads (figure 2A). The strand bias is similar to that seen in gnomAD v2.1.1 and could be explained if the variant was a mismapping artefact due to reads from TUBB2BP1, as the region of similarity extends distally by only 133 bp (figure 1). This mismapping hypothesis is also supported by three nearby TUBB2A-TUBB2BP1 cismorphisms, which can be observed in the same reads (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Allelic ratios for p.(Ala248Val) plotted against the number of negative strand reads supporting the variant in 58 individuals from the 100KGP. Five patients have an allelic fraction of >30%, and the variant is also supported by six or more of negative reads. These variants were considered to be real and form a discreet cluster compared with the 53 cases with low allelic fractions which are supported almost exclusively by +ve strand reads. Patients 1–5 are labelled P1–P5. (B) Read alignments shown in the Integrative Genomics Viewer for one case with likely artefact (upper) alongside the likely genuine variant in patient 5 (lower). The samples shown correspond to the red data points shown in panel A. Reads are sorted by base and shown using the squished option. Three other cismorphisms in the same reads are highlighted—the similarly low allelic fractions are consistent with a mismapping artefact. In the lower panel, as well as higher allelic fraction, multiple reads supporting the variant are seen on both strands. 100KGP, 100,000 Genomes Project; TUBB2A, beta-tubulin isotype 2A.

All five patients with apparently ‘genuine’ variants had neurodevelopmental presentations involving intellectual disability. Three patients were reported to have seizures (one with electroencephalogram showing hypsarrhythymia); three had hypoplasia of the corpus callosum; and three had asymmetric ventricules; the findings were not atypical of the clinical tubulinopathy spectrum (online supplemental table S2 and figure S1). In four of five of these cases, genome sequencing had been performed as parent–child trios, and in these, the variant was confirmed to have arisen de novo. The other 53 individuals spanned several disease areas and included unaffected family members, as well as germline samples from patients with cancer (online supplemental table S3).

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp002.xlsx (13KB, xlsx)

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp003.pdf (881.6KB, pdf)

Of the five patients where the variant was suspected to be genuine, three were white; one was Pakistani; and for one, ethnicity data were unavailable. Of the remaining 53 individuals, 34% were African/Caribbean; 30% were Asian; 13% were white; and for 23%, ethnicity data were not available. The increased prevalence of likely artefactual variant calls in individuals of African ethnicity mirrors the pattern seen in gnomAD. This may reflect TUBB2BP1 polymorphisms or additional tracts of common paralogous sequence in that population.

On a technical note, where Sanger sequencing is used for validation, primer design is critically important. In the original study by Cushion et al,1 a low allelic fraction was observed in the electropherogram. Rather than reflecting mosaicism, this was likely due to coamplification of TUBB2B (figure 1). We propose an alternative reverse primer (online supplemental table S4) that increases specificity towards TUBB2A and also demonstrate that poor primer design can lead to erroneous validation of NGS artefacts (online supplemental figure S2). Where similar methods are used, we recommend filtering p.(Ala248Val) variant calls at an allelic fraction of >20% and requiring >2 reads on both strands.

For one case, retrospective analysis of exome sequencing validated p.(Ala248Val) but further emphasised the impact of read lengths on mapping quality (online supplemental figure S3). Applying a similar analytical strategy on TUBB2B identified two patients from 100KGP with cortical brain malformations harbouring the corresponding p.(Ala248Val) variant (online supplemental material), with a similar clustering pattern observed (online supplemental figures S4, S5).

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp004.pdf (87KB, pdf)

Our cautionary tale highlights the difficulty in distinguishing bona fide gene-conversion events from mapping artefacts using short-read data. It is anticipated that increased uptake of long-read sequencing technologies will be beneficial to help fully resolve repetitive loci such as this.10 The value of plotting read-alignment statistics across a large cohort of individuals analysed using a uniform pipeline (eg, 100KGP) is also highlighted. It is likely that similar approaches may be useful for other genes where conversion events represent an important mutational mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Martin for performing Sanger validation in one of the families and the anonymous reviewer for suggesting we extend our analysis to include TUBB2B. We also thank the DDD study (www.ddduk.org) for sharing read alignment data for the overlapping case.

Footnotes

Twitter: @alistairp2011

Collaborators: Genomics England Research Consortium: J C Ambrose; P Arumugam; E L Baple; M Bleda; F Boardman-Pretty; J M Boissiere; C R Boustred; H Brittain; M J Caulfield; G C Chan; C E H Craig; L C Daugherty; A de Burca; A Devereau; G Elgar; R E Foulger; T Fowler; P Furió-Tarí; J M Hackett; D Halai; A Hamblin; S Henderson; J E Holman; T J P Hubbard; K Ibáñez; R Jackson; L J Jones; D Kasperaviciute; M Kayikci; A Kousathanas; L Lahnstein; K Lawson; S E A Leigh; I U S Leong; F J Lopez; F Maleady-Crowe; J Mason; E M McDonagh; L Moutsianas; M Mueller; N Murugaesu; A C Need; C A Odhams; C Patch; M B Pereira; D Perez-Gil; D Polychronopoulos; J Pullinger; T Rahim; A Rendon; P Riesgo-Ferreiro; T Rogers; M Ryten; K Savage; K Sawant; R H Scott; A Siddiq; A Sieghart; D Smedley; K R Smith; S C Smith; A Sosinsky; W Spooner; H E Stevens; A Stuckey; R Sultana; E R A Thomas; S R Thompson; C Tregidgo; A Tucci; E Walsh; S A Watters; M J Welland; E Williams; K Witkowska; S M Wood; M Zarowiecki.

Contributors: ATP and JCT conceived the work. VR, ATP and RLH performed data analysis. EG provided bioinformatics support and, along with MAMcC, gave critical comments. JRS, MS, AG, J-MC, DO and AEF recruited patients and reviewed clinical information. VR, ATP, MAMcC and JCT drafted the manuscript, which was revised and approved by all authors.

Funding: The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Programme and the Wellcome Trust (203141/Z/16/Z). This research was also made possible through access to the data and findings generated by the 100,000 Genomes Project. The 100,000 Genomes Project is managed by Genomics England Limited (a wholly owned company of the Department of Health and Social Care). The 100,000 Genomes Project is funded by the NIHR and National Health Service (NHS) England. The Wellcome Trust, Cancer Research UK and the Medical Research Council have also funded research infrastructure. The 100,000 Genomes Project uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Genomics England Research Consortium, J C Ambrose, P Arumugam, E L Baple, M Bleda, F Boardman-Pretty, J M Boissiere, C R Boustred, H Brittain, M J Caulfield, G C Chan, C E H Craig, L C Daugherty, A de Burca, A Devereau, G Elgar, R E Foulger, T Fowler, P Furió-Tarí, J M Hackett, D Halai, A Hamblin, S Henderson, J E Holman, T J P Hubbard, K Ibáñez, R Jackson, L J Jones, D Kasperaviciute, M Kayikci, A Kousathanas, L Lahnstein, K Lawson, S E A Leigh, I U S Leong, F J Lopez, F Maleady-Crowe, J Mason, E M McDonagh, L Moutsianas, M Mueller, N Murugaesu, A C Need, C A Odhams, C Patch, M B Pereira, D Perez-Gil, D Polychronopoulos, J Pullinger, T Rahim, A Rendon, P Riesgo-Ferreiro, T Rogers, M Ryten, K Savage, K Sawant, R H Scott, A Siddiq, A Sieghart, D Smedley, K R Smith, S C Smith, A Sosinsky, W Spooner, H E Stevens, A Stuckey, R Sultana, E R A Thomas, S R Thompson, C Tregidgo, A Tucci, E Walsh, S A Watters, M J Welland, E Williams, K Witkowska, S M Wood, and M Zarowiecki

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

HRA Committee East of England, Cambridge South (REC: 14/EE/1112).

References

- 1. Cushion TD, Paciorkowski AR, Pilz DT, Mullins JGL, Seltzer LE, Marion RW, Tuttle E, Ghoneim D, Christian SL, Chung S-K, Rees MI, Dobyns WB. De novo mutations in the beta-tubulin gene TUBB2A cause simplified gyral patterning and infantile-onset epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94:634–41. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brock S, Vanderhasselt T, Vermaning S, Keymolen K, Régal L, Romaniello R, Wieczorek D, Storm TM, Schaeferhoff K, Hehr U, Kuechler A, Krägeloh-Mann I, Haack TB, Kasteleijn E, Schot R, Mancini GMS, Webster R, Mohammad S, Leventer RJ, Mirzaa G, Dobyns WB, Bahi-Buisson N, Meuwissen M, Jansen AC, Stouffs K. Defining the phenotypical spectrum associated with variants in TUBB2A. J Med Genet 2021;58:33–40. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turnbull C, Scott RH, Thomas E, Jones L, Murugaesu N, Pretty FB, Halai D, Baple E, Craig C, Hamblin A, Henderson S, Patch C, O'Neill A, Devereau A, Smith K, Martin AR, Sosinsky A, McDonagh EM, Sultana R, Mueller M, Smedley D, Toms A, Dinh L, Fowler T, Bale M, Hubbard T, Rendon A, Hill S, Caulfield MJ, Genomes P, 100 000 Genomes Project . The 100 000 Genomes Project: bringing whole genome sequencing to the NHS. BMJ 2018;361:k1687. 10.1136/bmj.k1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bahi-Buisson N, Poirier K, Fourniol F, Saillour Y, Valence S, Lebrun N, Hully M, Bianco CF, Boddaert N, Elie C, Lascelles K, Souville I, Beldjord C, Chelly J, LIS-Tubulinopathies Consortium . The wide spectrum of tubulinopathies: what are the key features for the diagnosis? Brain 2014;137:1676–700. 10.1093/brain/awu082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Romaniello R, Arrigoni F, Fry AE, Bassi MT, Rees MI, Borgatti R, Pilz DT, Cushion TD. Tubulin genes and malformations of cortical development. Eur J Med Genet 2018;61:744–54. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cai S, Li J, Wu Y, Jiang Y. De novo mutations of TUBB2A cause infantile-onset epilepsy and developmental delay. J Hum Genet 2020;65:601–8. 10.1038/s10038-020-0739-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, Vitazka P, Millan F, Gibellini F, Vertino-Bell A, Smaoui N, Neidich J, Monaghan KG, McKnight D, Bai R, Suchy S, Friedman B, Tahiliani J, Pineda-Alvarez D, Richard G, Brandt T, Haverfield E, Chung WK, Bale S. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet Med 2016;18:696–704. 10.1038/gim.2015.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodan LH, El Achkar CM, Berry GT, Poduri A, Prabhu SP, Yang E, Anselm I. De novo TUBB2A variant presenting with anterior temporal Pachygyria. J Child Neurol 2017;32:127–31. 10.1177/0883073816672998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, Committee A, ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–23. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebbert MTW, Jensen TD, Jansen-West K, Sens JP, Reddy JS, Ridge PG, Kauwe JSK, Belzil V, Pregent L, Carrasquillo MM, Keene D, Larson E, Crane P, Asmann YW, Ertekin-Taner N, Younkin SG, Ross OA, Rademakers R, Petrucelli L, Fryer JD. Systematic analysis of dark and camouflaged genes reveals disease-relevant genes hiding in plain sight. Genome Biol 2019;20:97. 10.1186/s13059-019-1707-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp001.xlsx (13.5KB, xlsx)

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp002.xlsx (13KB, xlsx)

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp003.pdf (881.6KB, pdf)

jmedgenet-2020-107528supp004.pdf (87KB, pdf)