As China’s signature foreign policy initiative in the 21st century, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is rapidly becoming a global undertaking. Initially launched in 2013 as an international infrastructure project, BRI harkened back to the Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes connecting the East and the West. At first, BRI focused on two distinct prongs: a “belt” of overland economic corridors across Eurasia and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes through Southeast Asia to South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. By early 2021, however, BRI encompassed more than 140 countries representing close to 40% of global output and 63% of the world’s population.

Through the Health Silk Road (HSR), China has used BRI transportation networks—railroads, ports, airports, and logistics hubs—to provide medical and health care assistance to partner countries and assert China’s leadership in global health. The rapid expansion and global scope of BRI and HSR, examined in the Council on Foreign Relations independent task force report China’s Belt and Road: Implications for the United States, have been significant causes of concern for the Biden administration.1 Against the backdrop of COVID-19, HSR is set to further advance China’s role in global health governance; however, this does not justify an alarmist response from the United States.

ORIGINS OF THE HEALTH SILK ROAD

The term “Health Silk Road” first appeared in an October 2015 document issued in China by the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the predecessor of today’s National Health Commission, as a response to the central government’s requirements to contribute to the implementation of BRI.2 President Xi Jinping officially put forward the HSR concept in a 2016 visit to Uzbekistan. The following year, Beijing signed a memorandum of understanding with the World Health Organization committing to support HSR and improve health outcomes in BRI countries.

Despite the blessing of President Xi and the World Health Organization, HSR remained largely an undefined initiative with a wish list of projects prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Some of the proposed projects (e.g., providing personal protective equipment, medical supplies, and emergency medical assistance to BRI countries) had yet to materialize by March 2020. Other projects included under HSR, such as the Greater Mekong Subregion Disease Surveillance Network, had begun as part of joint disease prevention and control programs in Southeast Asia before the debut of HSR.

HEALTH SILK ROAD BUILDING DURING COVID-19

Although initially seen as a weakness, these amorphous arrangements have given HSR the flexibility to respond to new global health challenges. As China managed to curtail domestic transmission of COVID-19 and branded itself a winner in the fight against the pandemic, HSR opened “new cooperation space for BRI.”3 In a telephone call with Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte on March 16, 2020, for instance, Xi explicitly linked HSR to the pandemic: “China is ready to work with Italy to contribute to international cooperation on epidemic control and to the building of a ‘Health Silk Road.’ ”4 As a leading producer of personal protective equipment and COVID-19 vaccines, China focuses on providing medical supplies and equipment to build HSR during the pandemic. By late October 2020, it had sent more than 179 billion face masks and 1.73 billion protective suits to 150 countries.5 By late November 2021, it also had committed 1.6 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines to more than 100 countries.6 Roughly 40% of Chinese vaccines have been delivered to Southeast Asia, the preferred region for BRI and HSR construction.

China’s approach features multiple bilateral efforts under the BRI networks, which appear to be more efficient than the multilateral approach favored by the Western countries in global vaccine distribution. Chinese vaccine makers seem keener than their Western counterparts to help partner countries expand domestic vaccine manufacturing capabilities. They have built vaccine filling and finishing plants in Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco), Europe (Hungary, Serbia), Latin America (Brazil, Chile, Mexico), the Middle East (Turkey, United Arab Emirates), South Asia (Pakistan), and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia). Today, Chinese COVID-19 vaccines have claimed the largest market share in much of Asia and South America.7 These efforts have also boosted China’s international image. According to the Council on Foreign Relations report, following China’s delivery of critical medical products “BRI partners closely aligned with Beijing . . . have been more willing to give China the praise it seeks.”1

Still, China’s HSR building thus far has not fundamentally challenged US leadership in health-related development assistance. The China’s Belt and Road report discussed how substandard products and clumsy propaganda tarnished China’s early efforts to supply medical equipment and testing kits. Using health aid to expand the market share of Chinese medical products also makes Beijing’s rhetoric of distributing its vaccines as a “global public good” somewhat disingenuous.

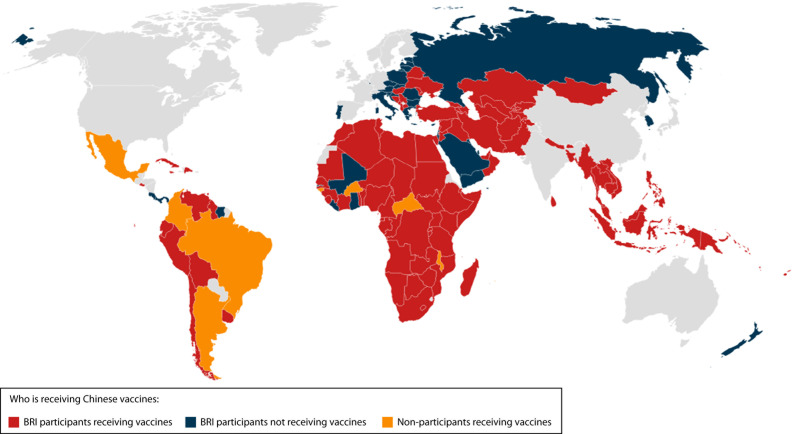

Unlike the United States, which shares vaccines primarily through donations, China sends most of its vaccines abroad as commercial supplies, which are in some cases more expensive than Western ones. As of November 30, 2021, only 7% of China’s vaccines that shipped overseas—119 million doses—involved grant assistance (i.e., donations).6 The relatively low efficacy rate of Chinese vaccines and the lack of transparency in revealing phase 3 clinical trial data have also undermined China’s vaccine diplomacy and the effectiveness of HSR in promoting BRI. Despite calls for prioritizing BRI countries to receive Chinese vaccines,8 37 of the 144 BRI countries are not currently receiving these vaccines (Figure 1). A growing number of countries, including those in Southeast Asia, are shifting away from Chinese vaccines.9

FIGURE 1—

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China’s Vaccine Diplomacy

THE US RESPONSE

The Biden administration views HSR, which seeks to expand both market share and international influence, as a clear geopolitical challenge to the United States. To counter China’s influence, the United States partnered with Australia, India, and Japan through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in March 2021 to finance, manufacture, and distribute at least 1 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines by the end of 2022.10

Theoretically, US–China competition in vaccine distribution helps build and sustain momentum for achieving a pandemic-free world. In reality, the vaccine diplomacy of the United States and its allies targets regions or countries that are strategically important to and prioritized by China’s HSR (e.g., Southeast Asia); relatively little interest is shown in satisfying the vaccine needs of low-income countries, where only 6% of people had received one dose of vaccine by the end of November 2021.11

Equally important, the overemphasis on US–China competition in terms of geopolitical influence and global leadership has led the Biden administration to forsake opportunities for cooperation between the countries. The US government could support the licensing of Chinese vaccine makers to mass produce mRNA vaccines, which would significantly increase the global vaccine supply. Also, building on the memorandum of understanding signed in November 2016, the United States and China could jointly support disease surveillance and response capacity building in the developing world. Framing the bilateral relationship in terms of strategic competition leaves little room for expanding cooperation in these areas.

FUTURE OF THE HEALTH SILK ROAD

On August 31, 2021, China unveiled new foreign aid guidelines that highlight BRI building as a main objective of aid provision.12 In the future, China may use partnerships forged during the pandemic to increase its health aid and expand the international market share of Chinese medical products. It may also invoke HSR to invest in additional global health projects, especially those that help BRI countries build core disease surveillance and response capacity. Whether this will lead to substantial investment in broader health-related development assistance projects, such as universal health coverage, remains to be seen.

Unless Beijing’s HSR agenda rules out cooperation with Washington, however, it is not in the interest of the United States to pursue an alarmist approach premised on US–China strategic competition. In developing initiatives to rival HSR, the Biden administration should consider tapping the large potential for cooperation between the two countries, from which the developing world would benefit immensely not only in terms of the present pandemic but in efforts to improve health security and strengthen health systems for future crises.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Samantha Kiernan for her research assistance and Dan Fox and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on earlier versions of the editorial.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lew JJ, Roughead G, Hillman J, Sacks D.2021. https://www.cfr.org/report/chinas-belt-and-road-implications-for-the-united-states/

- 2.China National Health and Family Planning Commission. [National Health and Family Planning Commission’s implementation plan for promoting “Belt and Road Initiative” health exchanges and cooperation. 2021. https://www.imsilkroad.com/news/p/97802.html

- 3.Zheng D.2021. http://www.qstheory.cn/llwx/2020-09/11/c_1126481118.htm

- 4.Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. President Xi Jinping’s telephone conversation with Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte. 2022. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/cevu/eng/zgdt/t1756887.htm

- 5.Xi J.2021. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1829373.shtml

- 6.Bridge Consulting. China COVID-19 vaccine tracker. 2021. http://bridgebeijing.com/our-publications/our-publications-1/china-covid-19-vaccines-tracker

- 7.Airfinity. 2021. http://airfinity.com/insights/sinovac-is-the-most-used-vaccine-in-the-world-with-943m-doses-delivered

- 8.Bo Y.2021. https://www.imsilkroad.com/news/p/444189.html

- 9.Mahtani S.2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/covid-vaccines-delta-china-asia/2021/08/10/24d0df60-f664-11eb-a636-18cac59a98dc_story.html

- 10.Biden J, Modi N, Morrison S, Suga Y.2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/03/12/remarks-by-president-biden-prime-minister-modi-of-india-prime-minister-morrison-of-australia-and-prime-minister-suga-of-japan-in-virtual-meeting-of-the-quad/

- 11.Kiernan S, Tohme S, Song G.2021. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/billions-committed-millions-delivered

- 12.Xie Y, Yu S.2021. http://www.cidca.gov.cn/2021-08/31/c_1211351312.htm