Abstract

The topical efficacies of foscarnet and acyclovir incorporated into a polyoxypropylene-polyoxyethylene polymer were evaluated and compared to that of 5% acyclovir ointment (Zovirax) by use of a murine model of cutaneous herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. All three treatments given three times daily for 4 days and initiated 24 h after infection prevented the development of the zosteriform rash in mice. The acyclovir formulation and the acyclovir ointment reduced the virus titers below detectable levels in skin samples from the majority of mice, whereas the foscarnet formulation has less of an antiviral effect. Reducing the number of treatments to a single application given 24 h postinfection resulted in a significantly higher efficacy of the formulation of acyclovir than of the acyclovir ointment. Acyclovir incorporated within the polymer was also significantly more effective than the acyclovir ointment when treatment was initiated on day 5 postinfection. The higher efficacy of the acyclovir formulation than of the acyclovir ointment is attributed to the semiviscous character of the polymer, which allows better penetration of the drug into the skin.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV type 2 (HSV-2) have the ability to become latent in sensory ganglia and to induce recurrent infections following reactivation (23). The frequencies of recurrent herpetic infections in the U.S. population are estimated to be 50 to 70% for HSV-1 and 23% for HSV-2 (36). Mucosal or skin surfaces are the usual sites of primary infection. Recurrent herpes labialis and herpes genitalis represent the most common clinical manifestations associated with HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections, respectively. Most recurrences are asymptomatic infections, and the shedding of herpesvirus under these conditions represents the most common form of transmission of this disease. Recurrences are associated with physical or emotional stress, fever, exposure to UV light, tissue damage, and immune suppression. The frequency of recurrences has also been correlated with the severity and duration of the initial infection (36). Although herpes is usually a mild disease in immunocompetent individuals, mucocutaneous herpetic infections are troublesome, especially for patients with frequent episodes. Moreover, immunocompromised patients have an increased risk of developing severe and more frequent herpetic infections.

During the past several decades, acyclovir has been the drug of choice for the treatment of herpetic infections. However, the emergence of acyclovir-resistant HSV isolates has been reported for immunocompromised patients (9) as well as for organ and bone marrow recipients (16, 33). Recurrent acyclovir-resistant genital herpes has also been described for an immunocompetent host (13). Foscarnet (trisodium phosphonoformate) has a broad antiviral spectrum and in vitro activity against all human viruses of the herpesvirus family, including cytomegalovirus, HSV, and varicella-zoster virus (5, 20). This drug is also effective against acyclovir-resistant HSV and varicella-zoster virus (4, 10, 25–27). Moreover, acyclovir-resistant HSV strains that become resistant to foscarnet may once again be susceptible to acyclovir (28). Because the intravenous administration of foscarnet is limited by the occurrence of nephrotoxic reactions, the development of topical formulations represents an attractive approach for the treatment of mucocutaneous herpetic infections, especially for those caused by acyclovir-resistant strains.

Topical formulations currently available for the treatment of mucocutaneous herpetic infections include 5% acyclovir ointment (Zovirax) and penciclovir cream formulation (Vectavir cold sore cream or Denavir cream in the United States). The currently available treatment, either topical or systemic, has only limited efficacy, particularly against symptomatic recurrent herpes. Treatment of recurrent herpes with topical acyclovir demonstrated no or only limited clinical benefit (6, 18, 22, 30). Wallin et al. demonstrated a limited but significant effect of topical foscarnet cream on time to healing for recurrent genital herpes (34). Conversely, no significant improvements in time to healing or loss of symptoms were observed for recurrent genital herpes in two other clinical trials (2, 24). Patients who received treatment in the prevesicular stage had a slightly reduced number of days with lesions (14). Treatment of herpes labialis in immunocompetent patients with penciclovir cream was reported beneficial for treatment started in the prodrome and erythema stages as well as in the papule and vesicle lesion stages (32).

In this study, we used a polymer composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene as a new vehicle for acyclovir and foscarnet to evaluate if the semiviscous character of this galenic form could allow efficient drug penetration into the skin, thereby increasing the efficacies of these drugs against HSV-1 cutaneous lesions in mice. The topical efficacies of acyclovir and foscarnet incorporated into the polymer matrix were also compared with that of the commercially available 5% acyclovir ointment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs.

Acyclovir (9-[(2-hydroxyethoxy)methyl]guanine) and foscarnet (trisodium phosphonoformate) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). [14C]foscarnet and [3H]acyclovir were obtained from Moravek (Brea, Calif.). The commercially available 5% acyclovir ointment was obtained from our local hospital pharmacy.

Preparation of the topical formulations.

For the formulations of acyclovir and foscarnet, we used a polymer (gel) composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene suspended in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 6.0) at a concentration of 18% (wt/wt). We selected a pH of 6.0 to correspond with the pH of the skin. For the formulation of foscarnet, the drug was first dissolved in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 6.0) at a concentration of 6 or 1% (wt/wt). The pH of the solution was then readjusted to 6.0 by adding a small amount of 1 N HCl. The solution was then mixed under agitation at 4°C with an equal volume of the polymer solution prepared in the same buffer to obtain a final foscarnet concentration of 3 or 0.5% (wt/wt). For the formulation of acyclovir, the antiviral agent was first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then mixed at 4°C with the polymer powder and phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 6.0) to obtain a final drug concentration of 5, 3, or 1% (wt/wt). The pH of the formulation of acyclovir was then readjusted to 6.0. The final amount of DMSO present in the formulation was 12.5%.

Virus strain.

HSV-1 strain F (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) was propagated in Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells (American Type Culture Collection) in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Canadian Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) supplemented with 0.22% sodium bicarbonate, 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 2% fetal bovine serum (EMEM + 2% FBS) to obtain a viral inoculum of 1.5 × 106 PFU/ml.

Plaque reduction assay.

Vero cells seeded in 24-well plates (Costar, Montréal, Québec, Canada) were infected with approximately 100 PFU of HSV-1 strain F in 0.5 ml of EMEM + 2% FBS for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell sheets were washed twice with fresh culture medium, overlaid with 0.5 ml of 0.6% SeaPlaque agarose (Marine Colloids, Rockland, Maine) in EMEM + 2% FBS containing increasing amounts of the drug under study, and incubated for 2 days at 37°C. Cells were then fixed with 10% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 20 min, washed with deionized water, and stained with 0.05% methylene blue.

Animal model.

Female hairless mice (SKH1; 5 to 7 weeks old; Charles River Breeding Laboratories Inc., St. Constant, Québec, Canada) were used throughout this study. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture containing 70 mg of ketamine hydrochloride (Rogar/STB Inc., Montréal, Québec, Canada) and 11.5 mg of xylazine (Miles Canada Inc., Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada) per kg of body weight. The virus was inoculated on the lateral side of the body in the left lumbar skin area. The skin was scratched six times in a crossed-hatch pattern with a 27-gauge needle held vertically. A viral suspension (5 × 105 PFU/50 μl) was rubbed for 10 to 15 s on the scarified skin area with a cotton-tipped applicator saturated with EMEM + 2% FBS. The scarified area was protected with a corn cushion (Schering-Plough Canada Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), which was held on the mouse body with surgical tape. The porous inner wall of the aperture of the corn cushion was made impermeable with tissue adhesive (Vet-bond, St. Paul, Minn.) prior to use to prevent drug absorption by the patch, which could act as a reservoir due to the accumulation of drug formulations. The aperture of the corn cushion was also closed with surgical tape. Mice were then returned to their cages and observed twice daily.

Treatments.

Different treatment regimens were evaluated in this study. For treatments initiated 24 h after infection (i.e., prior to the appearance of the zosteriform rash), the surgical tape closing the aperture of the corn cushion was removed and the scarified area was cleaned with a cotton-tipped applicator saturated with cold water to remove gel or ointment remaining from the last application. Fifteen microliters of the polymer alone, of the polymer containing foscarnet or acyclovir or a similar amount of acyclovir ointment was applied to the scarified area. The aperture of the corn cushion was closed with surgical tape to avoid systemic administration that could result from licking and grooming. For treatments initiated 5 days after infection (i.e., at the onset of the zosteriform rash), the corn cushion was removed. The entire zosteriform lesion was treated with 50 μl of the foscarnet or acyclovir formulation or a similar amount of acyclovir ointment. The treated area was protected with adhesive tape (Tegaderm; 3M Canada, London, Ontario, Canada) to prevent accidental systemic treatment that could occur due to licking of drug on the treated lesion. The treated area was cleaned with a cotton-tipped applicator saturated with cold water to remove gel or ointment remaining from the last application. Three daily treatments were given at 8:00 a.m., 2:00 p.m., and 9:00 p.m., as these times represent convenient times for self-application by patients. Seven to 13 animals per group were used for all experiments. The efficacies of the different treatments were evaluated by use of lesion scores, survival rates, and viral titers in skin samples. No blind evaluations between treatment groups were undertaken in this study.

Determination of viral titers in skin samples.

The extent of inhibition of HSV-1 replication in skin samples of mice was determined 5 days after virus inoculation. Preliminary experiments showed that viral titers in skin samples were maximum on days 4 and 5 postinfection. In brief, mice were sacrificed, and the site of virus inoculation and the lower flank (a skin area located between the virus inoculation site and the ventral midline but not touching the inoculation site) were excised. Skin samples were maintained in Hank's balanced salt solution (Canadian Life Technologies) at 4°C, blotted, weighed, and diluted with 1 ml of EMEM + 2% FBS. Viruses were released from skin samples by three cycles of sonication for 10 s each with a 5-s interval. The suspension obtained was centrifuged (1,100 × g for 15 min at 4°C). The supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until use. Titration of viruses in skin samples was done by determining PFU on Vero cells in cultures. We used a method essentially similar to that described for the plaque reduction assay, except that infection of cells with viruses extracted from skin samples was done by centrifuging the plates (750 × g for 45 min at 20°C).

In vivo skin penetration studies.

Mice were infected cutaneously with HSV-1 in order to obtain a fully developed zosteriform rash. On day 5 postinfection, a corn cushion was placed on the inoculation site of infected mice. A corn cushion was also placed on the left lumbar skin area of control uninfected mice. Fifteen microliters of 3% foscarnet or 5% acyclovir, incorporated in a solution or in the polymer matrix, each containing 1.8 μCi of the corresponding radiolabeled antiviral agent, was deposited into the aperture of the corn cushion as described above. Twenty-four hours following treatment, mice were sacrificed, and blood was withdrawn into heparinized tubes and centrifuged (10,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C) to separate plasma. Patches were removed carefully, and the test area was cleaned with a humidified cotton-tipped applicator and then dried with sterile gauze to remove formulations or ointment remaining from the application. The test area was tape stripped 15 times with approximately 1 cm of adhesive tape (Transpore Surgical Tape; 3M, St. Paul, Minn.) to remove the stratum corneum. Afterward, the skin was excised (approximately 2 cm2), and the epidermis and dermis were separated by heat splitting at 60°C in a water bath. Tissues were treated with tissue solubilizer (BTS-450; Beckman Instruments Inc., Irvine, Calif.), decolorized with hydrogen peroxide, and neutralized with glacial acetic acid. The radioactivity associated with plasma and each tissue sample was determined with a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Statistical analysis.

The areas under the curve (AUC) of the mean lesion scores for the different treatment groups between days 4 and 10 were compared by use of a one-way analysis of variance, followed as appropriate by a t test with Fisher's corrections for multiple simultaneous comparisons. The significance of the differences in the mortality rates between infected control and drug-treated groups was evaluated by use of a chi-square test. The significance of the differences in the viral titers between infected control and drug-treated groups was analyzed by use of a one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. The significance of differences between concentrations of acyclovir and foscarnet in stratum corneum tape strips was evaluated by comparing the AUC by use of an unpaired t test. The significance of differences between the levels of accumulation of acyclovir and foscarnet in the epidermis, the dermis, and plasma was determined by use of an unpaired t test. All statistical analyses were performed with a computer package (Statview+SE Software; Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, Calif.). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effective doses.

HSV-1 strain F is susceptible to both acyclovir and foscarnet when tested in Vero cells by a plaque reduction assay. The 50%, 90%, and 99% effective doses for acyclovir were 0.21, 0.38, and 0.42 μg/ml, whereas the corresponding values for foscarnet were 21.96, 41.55, and 45.95 μg/ml. This strain was approximately 100-fold less susceptible to foscarnet than to acyclovir.

Efficacy of treatments given three times daily for 4 days at 24 h postinfection.

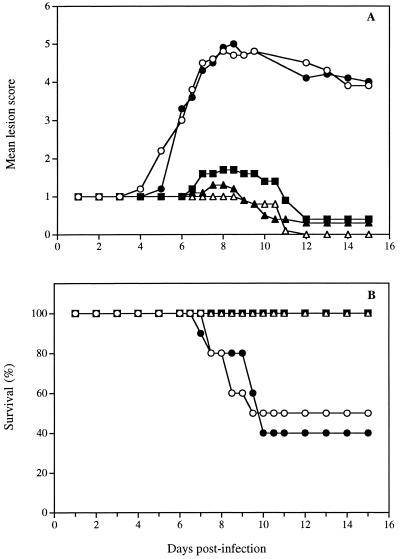

Figure 1A shows the time evolution of mean lesion scores for untreated infected mice and for infected mice treated with the polymer alone, with the polymer containing 3% foscarnet or 5% acyclovir, or with the acyclovir ointment. The evaluation of the lesion score was performed according to the criteria presented in Table 1. In untreated infected mice, no pathological signs of cutaneous infection were visible during the first 4 days following infection, and only the scarified area remained apparent. On day 5, herpetic skin lesions began to appear on some mice in the form of small vesicles distant from the inoculation site. On day 6, almost all untreated infected mice developed herpetic skin lesions in the form of a 4- to 5-mm-wide band extending from the spine to the ventral midline of the infected dermatome, similar to zoster-like infections. A maximal mean lesion score was observed on day 8. The mean lesion score decreased thereafter from day 12 to day 15 because of spontaneous regression of cutaneous lesions in some mice. For mice treated with the polymer alone, we observed a pattern largely similar to that for untreated infected mice, suggesting that the polymer alone had no therapeutic effect on the development of lesions. However, infected mice treated with all three drug formulations showed a significant reduction of the mean lesion score compared to untreated infected mice and mice treated with the polymer alone (Table 2). The decrease in the mean lesion score was less pronounced in mice receiving the polymer containing 0.5% foscarnet (data not shown). Acyclovir incorporated into the polymer at concentrations of 1, 3, and 5% demonstrated a dose-dependent effect in reducing the mean lesion score of infected mice, but the differences between doses were not significant (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Time evolution of the mean lesion score and survival of hairless mice infected cutaneously with HSV-1 strain F and treated soon after infection with the polymer alone (●), the polymer containing 3% foscarnet (■), the polymer containing 5% acyclovir (▴), or the acyclovir ointment (▵). Untreated infected mice (○) were used as controls. Treatment was started 24 h after the infection and was repeated three times daily for 4 days. Values represent the means for 7 to 10 animals per group.

TABLE 1.

Criteria used for the evaluation of herpetic cutaneous lesionsa

| Score | Appearance of the lesion |

|---|---|

| 0 | No visible infection |

| 1 | Infection at inoculation site in scarification area only |

| 2 | Infection at inoculation site only, with swelling, crusts, and erythema |

| 3 | Infection at inoculation site, with discrete lesions forming away from inoculation site |

| 4 | Rash visible around half of body but not yet confluent |

| 5 | Rash confluent but not yet necrotic or ulcerated |

| 6 | Complete rash with necrosis or ulceration, hind limb paralysis, bloating, and death |

Adapted from Lobe et al. (17).

TABLE 2.

Effects of topical treatment given with various schedules of administration on the development of herpetic cutaneous lesions in infected mice

| Schedulea | Treatmentb | AUCc |

P (compared to the following group)d:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | |||

| tid for 4 days starting 24 h postinfection | None | 33.78 ± 3.89 | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Gel alone | 35.23 ± 4.21 | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Gel with 5% ACV | 11.60 ± 2.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | NS | NS | ||

| Acyclovir ointment | 10.60 ± 0.28 | <0.01 | <0.01 | NS | NS | ||

| Gel with 3% PFA | 15.30 ± 2.88 | <0.01 | <0.01 | NS | NS | ||

| qd for 1 day starting 24 h postinfection | None | 38.12 ± 4.81 | <0.01 | NS | NS | ||

| Gel with 5% ACV | 20.81 ± 3.97 | <0.01 | <0.05 | NS | |||

| Acyclovir ointment | 32.15 ± 5.71 | NS | <0.05 | NS | |||

| Gel with 3% PFA | 34.75 ± 8.08 | NS | NS | NS | |||

| tid for 4 days starting 5 days postinfection | None | 54.00 ± 2.21 | NS | <0.01 | NS | NS | |

| Gel alone | 27.71 ± 8.28 | NS | <0.05 | NS | NS | ||

| Gel with 5% ACV | 17.08 ± 4.33 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | ||

| Acyclovir ointment | 36.17 ± 8.08 | NS | NS | <0.05 | NS | ||

| Gel with 3% PFA | 34.20 ± 8.11 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

tid, three times daily; qd, once daily.

ACV, acyclovir; PFA, foscarnet.

Values are means ± standard errors of the means, calculated as [(score on day 4 + score on day 10)/2] + sum of all scores between day 4 and day 10.

NS, not significant (i.e., P > 0.05). a, infected untreated mice; b, infected mice treated with the gel alone; c, infected mice treated with the gel containing 5% ACV; d, infected mice treated with the acyclovir ointment; e, infected mice treated with the gel containing 3% PFA.

Figure 1B shows the corresponding survival rates of the animal groups mentioned above. Fifty percent of untreated infected mice died from encephalitis between day 7 and day 10. In mice receiving the polymer alone, the lethality of infection was 60%, suggesting once again that the polymer alone had no therapeutic effect against the infection. On the other hand, all mice treated with the polymer containing 3% foscarnet or 5% acyclovir or with the acyclovir ointment survived the infection. In mice treated with a formulation containing 0.5% foscarnet, the survival rate was 90% (P, <0.001), whereas the survival rates of mice treated with topical formulations containing 1 and 3% acyclovir were 90% (P, <0.05) and 100% (P, < 0.001), respectively (data not shown).

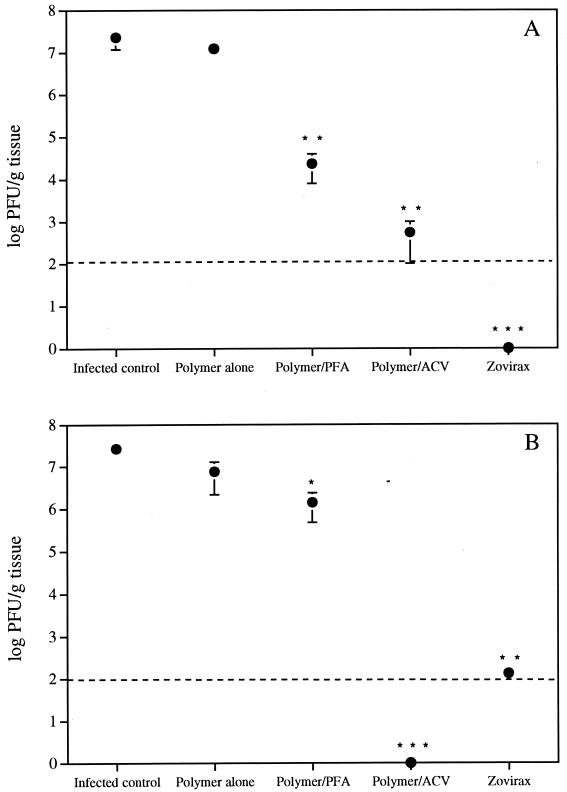

Figure 2 shows viral titers measured in skin samples corresponding to the inoculation site (Fig. 2A) and to the lower flank (Fig. 2B) on day 5 postinfection. The polymer alone could not significantly reduce the virus content either at the site of inoculation or in the lower flank. Treatment with the polymer containing 3% foscarnet resulted in a significant decrease in the virus content in skin samples. This decrease was more pronounced at the inoculation site than in the lower flank. Of prime interest, acyclovir incorporated into the polymer and acyclovir ointment caused a marked and significant reduction (often below the limit of detection of the assay) of the viral titers both at the inoculation site and in the lower flank.

FIG. 2.

Effect of formulations on titers of HSV-1 in the skin of hairless mice. Treatment was started 24 h after the infection and was repeated three times daily for 4 days. Viral titers in skin samples corresponding to the inoculation site (A) and to the lower flank (B) were determined on day 5 postinfection. Broken lines show the limit of detection of the assay. PFA, foscarnet; ACV, acyclovir. Values represent the means ± standard errors of the means for 7 to 10 animals per group. P values were <0.05 (∗), <0.005 (∗∗), and <0.001 (∗∗∗).

Effect of reducing the number of treatments.

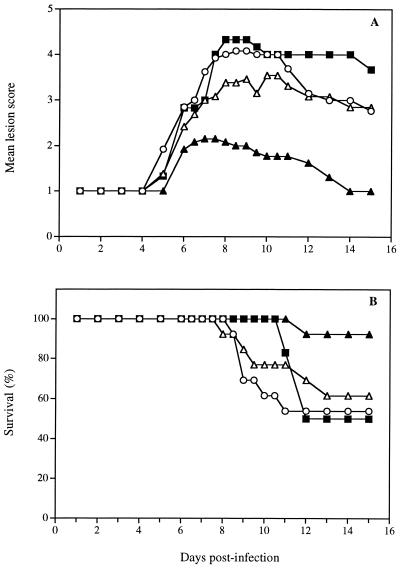

Figure 3A shows the time evolution of the mean lesion scores for untreated infected mice and for infected mice treated with a single application of polymer containing 3% foscarnet or 5% acyclovir or with the acyclovir ointment given at 24 h postinfection. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that the polymer alone did not exert any effect on the development of herpetic cutaneous lesions in this treatment regimen (data not shown). For mice treated with the formulation containing 3% foscarnet, the evolution of the mean lesion score was similar to that observed for untreated infected mice. Of prime interest, the topical formulation containing 5% acyclovir reduced significantly the development of cutaneous lesions compared to the results for untreated infected mice and mice treated with the acyclovir ointment (Table 2), which exerted only a modest effect. The formulation containing 3% foscarnet given only once delayed mortality but could not increase the survival rate compared to that of untreated infected mice (Fig. 3B). However, 5% acyclovir incorporated into the polymer significantly reduced the lethality of the infection (P, <0.001), but the acyclovir ointment did not. On the other hand, viral titers determined at the inoculation site and in the lower flank of mice treated with a single application of the polymer alone, polymer containing 3% foscarnet or 5% acyclovir or with 5% acyclovir ointment on day 5 postinfection were not markedly decreased compared to those in untreated infected mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Time evolution of the mean lesion score and survival of hairless mice infected cutaneously with HSV-1 strain F and treated 24 h postinfection with a single application of the polymer containing 3% foscarnet (■), the polymer containing 5% acyclovir (▴), or the acyclovir ointment (▵). Untreated infected mice (○) were used as controls. Values represent the means for 7 to 13 animals per group.

The topical efficacies of the different treatments were also evaluated after daily treatment for 4 days starting at 24 h postinfection. No major differences in efficacy could be seen between the polymer formulations containing 5% acyclovir or 3% foscarnet and the acyclovir ointment (data not shown). In addition, all topical treatments used in this regimen significantly increased survival rates (P, <0.05).

Effect of delaying the treatments.

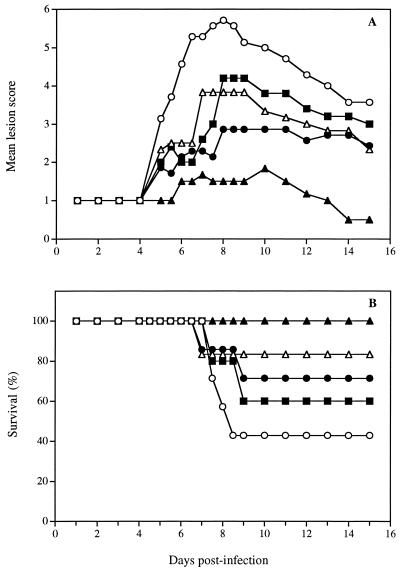

Figure 4 shows the time evolution of the mean lesion score (Fig. 4A) and survival (Fig. 4B) for untreated infected mice and for infected mice treated three times daily for 4 days starting on day 5 postinfection with the polymer alone, with the polymer containing 3% foscarnet or 5% acyclovir, or with the acyclovir ointment. The results showed that treatment with the polymer alone, with the polymer containing 3% foscarnet, or with the acyclovir ointment exerted a modest but not significant effect compared to the results obtained for untreated infected mice. In contrast, a significant reduction of the mean lesion score was observed for mice treated with the polymer containing 5% acyclovir compared to untreated infected mice and mice treated with the polymer alone or the acyclovir ointment (Table 2). Treatment with the 3% foscarnet formulation or with the acyclovir ointment significantly increased the survival rates of infected mice (P, <0.05). Of prime interest, all mice treated with the polymer containing 5% acyclovir survived the infection (P, <0.001).

FIG. 4.

Time evolution of the mean lesion score and survival of hairless mice infected cutaneously with HSV-1 strain F and treated later after infection with the polymer alone (●), the polymer containing 3% foscarnet (■), the polymer containing 5% acyclovir (▴), or the acyclovir ointment (▵). Untreated infected mice (○) were used as controls. Treatment was started on day 5 postinfection and was repeated three times daily for 4 days. Values represent the means for 7 to 10 animals per group.

In vivo skin penetration of antiviral agents.

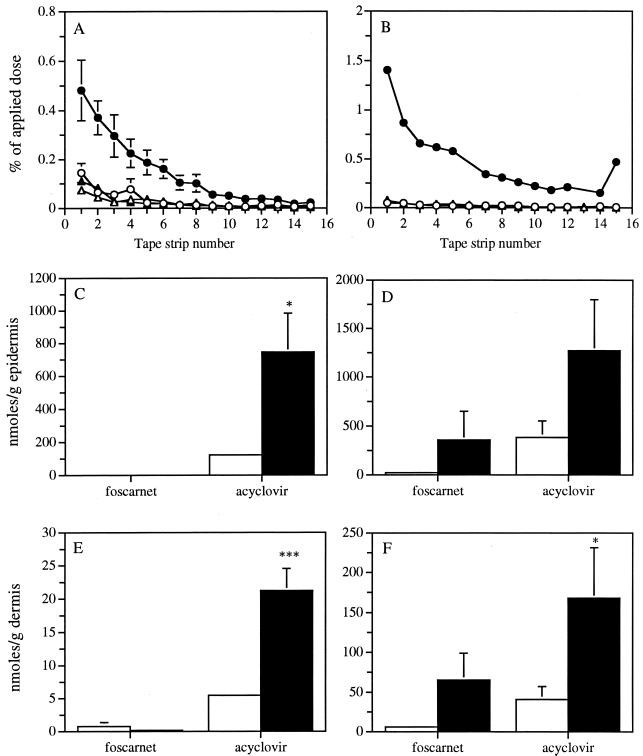

Figure 5 shows the distributions of foscarnet and acyclovir in skin tissues of uninfected (Fig. 5A, C, and E) and infected (Fig. 5B, D, and F) mice at 24 h after topical application either in phosphate buffer or in the polymer matrix to determine whether the polymer could increase the penetration of antivirals into the skin. The distributions of both formulations of foscarnet and of the buffered solution of acyclovir in the stratum corneum tape strips of uninfected and infected mice were similar. In contrast, the incorporation of acyclovir into the polymer matrix markedly increased the amount of drug recovered in the stratum corneum of both uninfected (P, <0.05) and infected (P, <0.005) mice, the increased drug penetration being more pronounced in infected mice. No or negligible amounts of foscarnet were found in the underlying epidermis and dermis of uninfected mice irrespective of the carrier used for the drug application. The concentrations of foscarnet in the epidermis and dermis of infected mice were higher when the drug was incorporated into the polymer, but a high variability between mice was observed. The concentrations of acyclovir were higher than those of foscarnet in the epidermis and dermis of both uninfected and infected mice irrespective of the carrier used. The concentrations of acyclovir incorporated into the polymer were 6.1- and 3.3-fold higher than that of the drug in the buffered solution in the epidermis of uninfected and infected mice, respectively. The concentrations of acyclovir administered in the polymer matrix were 3.9- and 4.1-fold higher than that of the drug in the buffered solution in the dermis of uninfected and infected mice, respectively. Infection of mice did not significantly increase the amount of acyclovir in the epidermis or in the dermis.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of foscarnet (▵ and ▴) and acyclovir (○ and ●) in skin tissues of uninfected (A, C, and E) and infected (B, D, and F) mice at 24 h after topical application either in phosphate buffer (open symbols) or in the polymer matrix (filled symbols). (A and B) Distributions of foscarnet and acyclovir in the stratum corneum tape strips. (C and D) Concentrations of foscarnet and acyclovir in the epidermis. (E and F) Concentrations of foscarnet and acyclovir in the dermis. Values represent the means for four to six animals per group. Error bars show standard errors of the means. P values were <0.05 (∗) and <0.001 (∗∗∗).

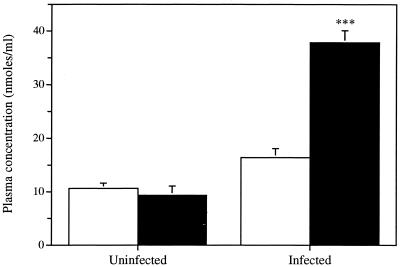

Figure 6 shows the concentration of acyclovir in the plasma of uninfected and infected mice at 24 h after topical application either in phosphate buffer or in the polymer matrix. Similar concentrations of acyclovir were found in the plasma of uninfected mice for both formulations. The concentration of acyclovir in the plasma of infected mice was 2.3-fold higher when the drug was incorporated into the polymer matrix than when it was present in the buffered solution. Infection of mice resulted in a fourfold increase in the concentration in plasma of acyclovir administered within the polymer matrix. No or negligible amounts of foscarnet were recovered in the plasma of uninfected or infected mice, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Concentration of acyclovir in plasma of uninfected and infected mice at 24 h after topical application either in phosphate buffer (open bars) or in the polymer matrix (filled bars). Values represent the means for four to six animals per group. Error bars show standard errors of the means. The P value was <0.001 (∗∗∗).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have evaluated the efficacies of foscarnet and acyclovir incorporated within a polymer matrix in comparison with that of acyclovir ointment in a murine model of cutaneous HSV-1 infection. The zosteriform model, even though it involves only the primary infection, provides a useful analog of recurrent disease (3). In this model, the virus is inoculated in the skin, where the primary infection occurs. From this site, the virus spreads, probably by retrograde axonal flow, to sensory ganglia and the central nervous system. Thereafter, the virus reaches axons that innervate skin within the same dermatome as the inoculation site, spreads via orthograde flow to the skin, and produces herpetic lesions within the affected dermatome. In our model, viral titers measured 24 h postinfection at the inoculation site of untreated infected mice were below the detectable level (data not shown), suggesting that the virus was disseminated to sensory ganglia. Thereafter, the virus returned to the skin and was again detectable at the inoculation site on day 2 postinfection. Ijichi et al. (11) also reported that viral titers measured at the inoculation site gradually decreased and were undetectable 12 h after infection, whereas high viral titers were recovered 24 h postinfection. Viral titers determined both at the inoculation site and in the lower flank reached a maximum value on day 5 postinoculation and then rapidly decreased on day 7. Virus clearance in cutaneous HSV infections is mediated by the host immune system and is essentially a property of CD4+ T cells (19). In spite of the complete clearance of the virus by day 7, severe ulcerations continued from day 6 to day 12 and might have been partly due to nonspecific cellular immune responses of infected mice (29). If adequate virus clearance does not occur, the virus spreads into the central nervous system, and mice develop encephalitis and ultimately die. Viral titers were detectable in the brains of some mice as soon as day 6 postinfection (data not shown), and mice began to die at about day 7.

All treatments given three times daily for 4 days and initiated 24 h postinfection demonstrated a marked therapeutic effect on the development of herpetic cutaneous infections, on the basis of mean lesion scores. The formulation of acyclovir within the polymer matrix and the acyclovir ointment reduced viral titers in skin samples below detectable levels, whereas the formulation of foscarnet within the polymer matrix exerted less of an effect on this parameter. Because in our model, virus returns to the skin between 24 and 48 h after inoculation, the marked therapeutic effect observed with all topical treatments given 24 h postinfection should correspond to an inhibition of secondary virus dissemination. This type of treatment could thus mimic the situation in which a patient initiates therapy at the onset of the prodrome phase. Reducing the treatment to a single application of topical formulations given 24 h after the infection resulted in a significantly higher efficacy of acyclovir incorporated within the polymer matrix than of the acyclovir ointment.

A delay in the initiation of topical treatments to 5 days postinfection was characterized by an increase in the mean lesion score and an increase in the mortality of infected mice treated with the formulation of foscarnet and with the acyclovir ointment given three times daily for 4 days. Many authors suggest that the observed lack of efficacy of topical treatments in delayed therapy could be due to the fact that the phase of virus replication in the zosteriform model occurs before the appearance of symptoms and the initiation of treatment. Kristofferson et al. reported that topical treatments with foscarnet initiated 12, 24, and 48, or 72 h after infection were markedly effective, moderately effective, and ineffective, respectively (14). Lee et al. (15) also showed that the topical efficacy of acyclovir in 1- and 2-day-delayed treatments was essentially the same as that for treatment started immediately after infection, while the topical efficacy of a 3-day-delayed treatment was much lower. Ijichi et al. (11) also showed reduced effects of late therapy with 1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-E-5-(2-bromovinyl)uracil cream. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, a lack of therapeutic effect on disease development was reported when treatment was initiated on the appearance of the first clinical signs of infection in clinical trials. Interestingly, the results clearly showed that the application of acyclovir incorporated within the polymer on day 5 postinfection was significantly more efficacious than the acyclovir ointment, as evidenced by the reduced mean lesion scores. At this time, the zosteriform rash has started to develop and large amounts of virus have reached the skin. This type of treatment could thus mimic the situation in which a patient initiates therapy at the appearance of lesions. We could not, however, determine viral titers in skin samples of treated animals because untreated infected mice began to die at about day 7 or 8 postinfection. In addition, in untreated infected mice that survived the infection, virus tended to disappear from the skin after day 7, making the interpretation of results difficult (data not shown).

An important consideration in the treatment of herpetic mucocutaneous infections is the delivery of adequate amounts of drugs at the site(s) of infection (31). It is well known that DMSO, at a concentration of higher than 70%, has the ability to accelerate the skin penetration of a variety of substances mainly because it elutes components of the stratum corneum, delaminates the horny layer, and denatures proteins (35). However, the small amount of DMSO (12.5%) in the formulation of acyclovir could not explain its better efficacy. Skin penetration studies revealed that the concentrations of acyclovir recovered in different parts of the skin (stratum corneum, epidermis, and dermis) were significantly higher when the drug was administered in the polymer matrix than when it was administered in a buffered solution. We thus proposed that the incorporation of acyclovir into the polyoxypropylene-polyoxyethylene polymer could lead to a better targeting of sites of viral replication, most probably because of the semiviscous character of this galenic form, which could allow efficient drug penetration into the smallest irregularities of the skin. In infected mice, the presence of crusts due to the scarification and to the zosteriform rash resulted in a significantly higher concentration of acyclovir in the stratum corneum compared to uninfected mice. In addition, we observed an increase in the systemic concentration of acyclovir, which could treat encephalitis or a disseminated disease and might therefore explain the difference in mortality observed with the polymer formulation.

We previously showed that the incorporation of foscarnet into the polymer matrix markedly increased its efficacy over that of the drug contained in a buffered solution (21). However, the efficacy of the formulation of foscarnet was lower than that of acyclovir, irrespective of the schedules of administration tested. This result can be attributed to its high anionic character, which limits its intracellular penetration and thereby limits its efficacy compared to that of acyclovir, which is neutral at a physiological pH (8). In that respect, studies performed in our laboratory with Franz diffusion cells and a polytetrafluoroethylene membrane (pore size, 5 μm), which mimics the hydrophobic property of human skin (12, 37), have indicated that acyclovir incorporated within the polymer diffuses at least 30 times more efficiently than foscarnet through such a membrane (data not shown). This result suggests that differences in interactions between the polymer matrix and these two antiviral agents could markedly influence their penetration into the skin. Skin penetration studies indeed revealed that the concentrations of foscarnet in the different skin layers as well as in the plasma were lower than those of acyclovir irrespective of the carrier used for drug administration. Moreover, the difference in the sensitivities of HSV-1 strain F to both drugs may also contribute to the better efficacy of the formulation of acyclovir. Descamps et al. reported a similar ranking for the topical efficacies of these two drugs given as a 1% water-soluble ointment against cutaneous HSV-1 infections in mice (7). Conversely, Alenius et al. showed that acyclovir, both in DMSO and in propylene glycol, is consistently less active than a foscarnet cream when tested on HSV-1 cutaneous lesions in guinea pigs (1).

In conclusion, our results showed that a polymer composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene could represent a suitable vehicle for antiviral agents for topical treatments of herpetic cutaneous lesions. Such an approach could also be convenient for the treatment of genital herpes. Studies should now be undertaken to define the respective roles of topical efficacy, which takes place in basal skin or mucosal layers, and systemic efficacy in treating herpetic lesions either prior to or at the time of the appearance of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from Infectio Recherche Inc.

We thank Rabeea F. Omar and Guy Boivin for constructive comments and helpful discussions. We also thank Hélène Cormier for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alenius S, Berg M, Froberg F, Eklind K, Lindborg B, Öberg B. Therapeutic effects of foscarnet sodium and acyclovir on cutaneous infections due to herpes simplex virus type 1 in guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:569–573. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton S E, Munday P E, Kinghorn G R, van der Meijden W I, Stolz E, Notowicz A, Rashid S, Schuller J L, Essex-Cater A J, Kuijpers M H M, Chanas A C. Topical treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infections with trisodium phosphonoformate (foscarnet): double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre study. Genitourin Med. 1986;62:247–250. doi: 10.1136/sti.62.4.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blyth W A, Harbour D A, Hill T J. Pathogenesis of zosteriform spread of herpes simplex virus in the mouse. J Gen Virol. 1984;65:1477–1486. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-9-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatis P A, Miller C H, Schrager L E, Crumpacker C S. Successful treatment with foscarnet of an acyclovir-resistant mucocutaneous infection with herpes simplex virus in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:297–300. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902023200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chrisp P, Clissold P. Foscarnet: a review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Drugs. 1991;41:104–129. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199141010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corey L, Nahmias A J, Guinan M E, Benedetti J K, Critchlow C W, Holmes K K. A trial of topical acyclovir in genital herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1313–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206033062201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Descamps J, De Clercq E, Barr P J, Jones A S, Walker R T, Torrence P F, Shugar D. Relative potenties of different antiherpes agents in the topical treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex virus infection of athymic nude mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:680–682. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.5.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dusserre N, Lessard C, Paquette N, Perron S, Poulin L, Tremblay M, Beauchamp D, Désormeaux A, Bergeron M G. Encapsulation of foscarnet in liposomes modifies drug intracellular accumulation, in vitro anti-HIV-1 activity, tissue distribution, and pharmacokinetics. AIDS. 1995;9:833–841. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Englund J A, Zimmerman M E, Swierkosz E M, Goodman J L, Scholl D R, Balfour H H. Herpes simplex virus resistant to acyclovir. A study in a tertiary care center. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:416–422. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-3-112-6-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erlich K S, Jacobson M A, Koehler J E, Follansbee S E, Drennan D P, Gooze L, Safrin S, Mills J. Foscarnet therapy for severe acyclovir-resistant herpes virus type-2 infections in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). An uncontrolled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:710–713. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ijichi K, Ashida N, Varia S, Machida H. Topical treatment with BV-araU of immunosuppressed and immunocompetent shaved mice cutaneously infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. Antiviral Res. 1993;21:47–57. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90066-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juhász J, Mahashabde S, Sequeira J. Comparison of in vitro release rates of nitroglycerin by diffusion through a Teflon membrane to the USP method. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1996;22:1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kost R G, Hill E L, Tigges M, Strauss S E. Brief report: recurrent acyclovir-resistant genital herpes in an immunocompetent patient. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1777–1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristofferson A, Ericson A-C, Sohl-Åkerlund A, Datema R. Limited efficacy of inhibitors of herpes simplex virus DNA synthesis in murine models of recrudescent disease. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1157–1166. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-6-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee P H, Su M H, Kern E R, Higuchi W I. Novel animal model for evaluating topical efficacy of antiviral agents: flux versus efficacy correlations in the acyclovir treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex virus type 1 (HVS-1) infections in hairless mice. Pharm Res. 1992;9:979–989. doi: 10.1023/a:1015838007864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljungman P, Ellis M N, Hackman R C, Shepp D H, Meyers J D. Acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus causing pneumonia after marrow transplantation. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:244–248. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lobe D C, Spector T, Ellis N. Synergistic topical therapy by acyclovir and A1110U for herpes simplex virus induced zosteriform rash in mice. Antiviral Res. 1991;15:87–100. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90027-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luby J P, Gnann J W, Alexander W J, Hatcher V A, Friedman-Kien A E, Klein R J, Keyserling H, Nahmias A, Mills J, Schachter J, Douglas J M, Corey L, Sacks S L. A collaborative study of patient-initiated treatment of recurrent genital herpes with topical acyclovir or placebo. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:1–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manickan E, Rouse B T. Roles of different T-cell subsets in control of herpes simplex virus infection determined by using T-cell-deficient mouse models. J Virol. 1995;69:8178–8179. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8178-8179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Öberg B. Antiviral effects of phosphonoformate. Pharmacol Ther. 1989;19:387–415. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(82)90074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piret J, Gourde P, Cormier H, Désormeaux A, Beauchamp D, Tremblay M J, Juhász J, Bergeron M G. Efficacy of gel formulations containing free or liposomal foscarnet in a murine model of cutaneous herpes simplex type-1 infection. J Liposome Res. 1999;9:181–198. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reichman R C, Badger G J, Guinan M E, Nahmias A J, Keeney R E, Davis L G, Ashikaga T, Dolin R. Topically administered acyclovir in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex genitalis: a controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:336–340. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roizman B, Sears A E. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Chanock R M, Hirsch M S, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, editors. Fields virology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1795–1841. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacks S L, Portnoy J, Lawee D, Schlech W, Aoki F Y, Tyrrell D L, Poisson M, Bright C, Kaluski J. Clinical course of recurrent genital herpes and treatment with foscarnet cream: results of a Canadian multicenter trial. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:178–186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safrin S, Assaykeen T, Follansbee S, Mills J. Foscarnet therapy for acyclovir-resistant mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus infection in 26 AIDS patients: preliminary data. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1078–1084. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safrin S, Berger T G, Gilson I, Wolfe P R, Wolfsy C B, Mills J, Biron K K. Foscarnet therapy in five patients with AIDS and acyclovir-resistant varicella-zoster virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:19–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safrin S, Crumpacker C, Chatis P, Davis R, Hafner R, Rush J, Kessler H A, Landry B, Mills J. A controlled trial comparing foscarnet with vidarabine for acyclovir-resistant mucocutaneous herpes simplex in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. The AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:551–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108223250805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safrin S, Kemmerly S, Plotkin B, Smith T, Weissbach N, De Veranez D, Phan L D, Cohn D. Foscarnet-resistant herpes simplex virus infection in patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:193–196. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simmons A, Nash A A. Zosteriform spread of herpes simplex virus as a model of recrudescence and its use to investigate the role of immune cells in prevention of recurrent disease. J Virol. 1984;52:816–821. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.816-821.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spruance S L, Crumpacker C S. Topical 5 percent acyclovir in polyethylene glycol for herpes simplex labialis: antiviral effect without clinical benefit. Am J Med. 1982;73:315–319. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spruance S L, Freeman D J. Topical treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections. Antiviral Res. 1990;14:305–321. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(90)90050-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spruance S L, Rea T L, Thoming C, Tucker R, Saltzman R, Boon R. Penciclovir cream for the treatment of herpes simplex labialis. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Topical Penciclovir Collaborative Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277:1374–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verdonck L F, Cornelissen J J, Smit J, Lepoutre J, de Gast G C, Dekker A W, Rozenberg-Arska M. Successful foscarnet therapy for acyclovir-resistant mucocutaneous infection with herpes simplex virus in a recipient of allogeneic BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;11:177–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallin J, Lemestedt J O, Ogenstad S, Lycke E. Topical treatment of recurrent genital herpes infections with foscarnet. Scand J Infect Dis. 1985;17:165–172. doi: 10.3109/inf.1985.17.issue-2.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walters K A. Penetration enhancers and their use in transdermal therapeutic systems. In: Hadgraft J, Guy R H, editors. Transdermal drug delivery: developmental issues and research initiatives. Vol. 35. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1989. pp. 197–245. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitley R J. Herpes simplex viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Chanock R M, Hirsch M S, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, editors. Fields virology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1843–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu S T, Shiu G K, Simmons J E, Bronaugh R L, Skelly J P. In vitro release of nitroglycerin from topical products by use of artificial membranes. J Pharm Sci. 1992;81:1153–1156. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600811204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]