Abstract

In conventional adaptive immune responses, upon recognition of foreign antigens, naive CD4+ T lymphocytes are activated to differentiate into effector/memory cells. In addition, emerging evidence suggests that in the steady state, naive CD4+ T cells spontaneously proliferate in response to self-antigens to acquire a memory phenotype (MP) through homeostatic proliferation. This expansion is particularly profound in lymphopenic environments but also occurs in lymphoreplete, normal conditions. The ‘MP T lymphocytes’ generated in this manner are maintained by rapid proliferation in the periphery and they tonically differentiate into T-bet-expressing ‘MP1’ cells. Such MP1 CD4+ T lymphocytes can exert innate effector function, producing IFN-γ in response to IL-12 in the absence of antigen recognition, thereby contributing to host defense. In this review, we will discuss our current understanding of how MP T lymphocytes are generated and persist in steady-state conditions, their populational heterogeneity as well as the evidence for their effector function. We will also compare these properties with those of a similar population of innate memory cells previously identified in the CD8+ T lymphocyte lineage.

Keywords: CD4+ T lymphocytes, memory, homeostasis

Features and functions of ‘memory-phenotype’ CD4+ T cells

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

CD4+ T lymphocytes are essential for functional adaptive immune responses. In response to infection, naive CD4+ T cells that recognize specific foreign antigens robustly proliferate to give rise to effector cells that contribute to host defense. After pathogen elimination, most effector T lymphocytes die, leaving a small residual population of foreign-antigen-specific memory cells that survive long enough to provide the host with immunological memory. Under steady-state conditions where overt, ongoing infection is absent, CD4+ T lymphocytes are thought to occupy both naive and memory compartments. Their homeostasis is strictly regulated by various mechanisms provided through T-cell receptor (TCR), co-stimulatory and cytokine signaling (1).

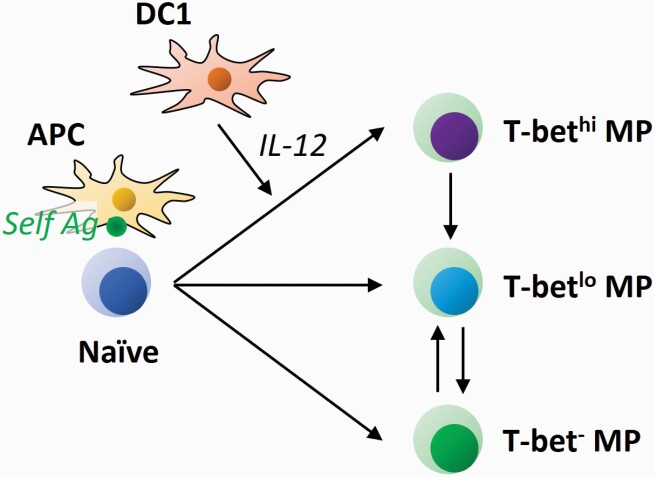

In addition to conventional T-cell activation that is driven by overt stimulation with foreign antigens, there is accumulating evidence suggesting that naive CD4+ T lymphocytes can spontaneously acquire a memory phenotype (MP, i.e. CD44hi) independent of explicit foreign antigens, being presumably induced by recognition of self-antigens in the steady state (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, these ‘MP cells’ can exert innate immune function, i.e. producing IFN-γ in response to IL-12 (an inflammatory cytokine) in the absence of antigen recognition and augmenting the later development of antigen-specific immune responses, thereby contributing to host protection from pathogen infection (2, 3). We have proposed that together with their CD8+ counterparts (some of which are also referred to as innate and virtual memory cells), CD4+ MP cells significantly contribute to the lymphocyte-mediated innate immunity provided by NK cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) (4–6).

Fig. 1.

Two activation pathways of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes. T cells are originally generated in the thymus. In positive selection, thymocytes are tested for their self-reactivity and only those with mild TCR affinity to self-antigen (Ag) are signaled to survive as naive T cells. In peripheral lymphoid tissues, mature naive CD4+ T cells that strongly recognize foreign antigens are activated to differentiate into effector/memory cells. On the other hand, those that weakly react with self-antigens mildly proliferate to give rise to MP cells.

In this article we discuss recent progress in our understanding on how MP CD4+ T lymphocytes are generated and maintained in the periphery as well as their phenotypic and functional properties.

Definition of MP T lymphocytes

Conventional CD4+ T lymphocytes are composed of naive (CD44lo CD62Lhi) and memory (CD44hi CD62Llo–hi) cell compartments at homeostasis (1). The existence of the latter cell population in unimmunized, normal mice has been known for >30 years (7, 8). In young animals, this population accounts for ~10% of the total CD4+ T lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid tissues and increases in size with age (2). Because its phenotype closely resembles that of foreign-antigen-specific ‘authentic’ memory cells, it was tacitly assumed that the same population represents conventional memory T lymphocytes specific for commensal and/or food antigens.

However, this simple assumption has been now called into question on several counts. First, CD44hi CD4+ T lymphocytes can be generated independent of explicit foreign antigen stimulation. Thus, this cell population is present in a similar frequency in specific pathogen-free (SPF), germ-free (GF) and antigen-free (AF) mice; the AF mice being deprived of both commensal and food antigens (2, 7–9). Similarly, TCR-transgenic CD4+ T lymphocytes that are specific for foreign antigens maintain a CD44hi fraction even in unimmunized mice where the same antigens are absent (3, 10). These observations strongly suggest that self-antigens rather than foreign antigens are the dominant driving force for the steady-state generation of CD44hi CD4+ T cells although it does not rule out the possible minor contribution of environmental antigens derived from commensal microbiota and/or food. This hypothesis is further supported by the finding that, in the steady state, CD44hi CD4+ T cells have higher expression levels of CD5, a marker that reflects the strength of TCR affinity to self-antigens (11), than do their naive counterparts (T. Kawabe, unpublished observation). The notion that the former T-cell population is driven by self-antigens is thus not surprising given that all foreign-antigen-recognizing CD4+ T lymphocytes by definition should possess TCRs with mild affinity to self-antigens because of thymic positive selection (12).

The second argument that CD44hi CD4+ T cells at homeostasis are distinct from conventional memory cells lies in the differing mechanisms they employ for their maintenance. Thus, conventional memory cells are thought to be generally quiescent (13, 14). On the other hand, ~30% of CD44hi CD4+ T cells seen in uninfected animals are in cell cycle at any given time point during homeostasis (14), and over a 4-week period ~60% have divided at least once (15). In this regard, CD4+ T lymphocytes that have an activated phenotype and display tonic proliferation also exist in human cord blood and the fetus as CD45RAlo CD45ROhi Ki67+ cells (16, 17). Because in these tissues encounter with foreign antigens is likely to be very limited or non-existent, such human cells may be driven by self-antigen recognition.

On the basis of the above observations, explicit foreign-antigen-independent CD44hi CD4+ T cells are now thought to belong to a population distinct from conventional memory T lymphocytes; we have been referring to the former population as ‘MP T lymphocytes’. As summarized above, a majority of CD4+ MP cells seem to develop from naive precursors in a self-antigen recognition-dependent manner and are maintained in the periphery during adult life (Fig. 1).

In the case of CD8+ MP T lymphocytes, two sub-populations—virtual memory T cells (TVM cells) and innate memory T cells (TIM cells)—have been previously described (18–21). Both have a similar CD44hi phenotype and thus it is difficult to precisely distinguish these two populations in the periphery. However, their sites of development are different; TVM cells are generated in an IL-15-dependent manner from peripheral naive precursors (22, 23), whereas TIM cells are induced in the thymus in a manner dependent on NKT cell-derived IL-4 (21). Whether similar distinctions apply to CD4+ MP cells remains to be determined.

Interestingly, CD8+ MP T lymphocytes are largely CD44hi CD62Lhi, a phenotype that sharply contrasts with that of CD4+ MP cells where the CD44hi CD62Llo sub-population dominates (2, 24). The explanation for this distinction is currently unclear but may reflect differences in responsiveness to the cytokines IL-7 and IL-15 that play essential roles in memory T-cell maintenance (1). In this regard, CD8+ MP cells have higher levels of CD122 (a subunit of the IL-15 receptor) than do their CD4+ counterparts (25) and, as a result, the former population may be maintained more efficiently as the most differentiated form of ‘central memory’-phenotype cells. Thus, in the case of CD4+ MP cells, because CD122 expression is relatively low (25) and IL-7 availability is limited in the steady state (26), their terminal differentiation as memory cells may be inhibited. In that situation responses to available antigens including self may dominate, which could account for their CD44hi CD62Llo phenotype as well as more rapid proliferation.

Role of homeostatic proliferation in MP cell generation

The mechanisms of generation of MP CD4+ T lymphocytes have been traditionally studied using mouse models where CD4+ T cells are transferred into congenic, lymphopenic mice. In such lymphopenic environments, donor cells exhibit proliferative behavior called ‘homeostatic proliferation (HP)’ in order to recover lymphosufficiency (27, 28). Because this response occurs in various types of lymphopenic mice including irradiated, CD90 monoclonal antibody-treated and Rag1/2-deficient animals, lymphopenia itself is thought to be the trigger for the observed proliferation.

To analyze HP, naive CD4+ T lymphocytes are typically labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and transferred into recipient mice. In such conditions donor cells exhibit two types of cell division: slow (homeostatic) and fast (spontaneous) (Fig. 2). The former response is defined as a cell division every 2–3 days, whereas the latter is defined as one or more division(s) a day (29, 30). Through slow HP, naive CD4+ T cells only minimally up-regulate CD44 without altering expression levels of CD62L, CD69 or CD25, suggesting that the same response largely contributes to their own turnover (30). Slow proliferation of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes is typically driven by recognition of self-antigens. Thus, such proliferation is equally present in lymphopenic mice raised under SPF, GF or AF conditions (29, 31) but is almost absent in major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II)-deficient animals (27, 32, 33). It has also been reported that CD5hi naive cells proliferate more rapidly than their CD5lo counterparts (within the slow proliferating population) (34), suggesting a critical role for self-recognition in slow HP.

Fig. 2.

Slow and fast HP of naive CD4+ T cells. In lymphopenic environments, some naive CD4+ T lymphocytes slowly proliferate to give rise to CD44lo–int CD62Lhi T cells, whereas a few clones divide more rapidly to acquire a CD44hi CD62Llo phenotype. The different colors reflect different T-cell clones.

In addition to self-antigens, slow HP is dependent on IL-7 homeostatically produced by radioresistant cells including fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) in lymph nodes (1, 26, 30, 32, 35). Indeed, in aged mice where lymph node structure is altered and access to FRCs is limited, this slow proliferation is hampered (36). Moreover, slow proliferation is known to be independent of CD28 co-stimulation as well as being independent of regulatory T cell (Treg cell)-mediated suppression (37–40).

On the other hand, fast proliferation converts naive CD4+ T cells into cells with an MP (30) and is known to be regulated quite differently. Similar to slow proliferation, fast HP requires host-derived MHC II expression (27, 32, 33), and dendritic cells (DCs) play a critical role in their response (41). This suggests the importance of antigen recognition in rapid proliferation. However, in contrast to slow HP, fast proliferation is significantly promoted by co-stimulatory CD28 and OX40 signaling (37, 40, 42) and, in the case of CD8+ T cells, by IL-15 and/or IL-2 (43–45). Moreover, fast HP is inhibited by Treg cells and TGF-β (31, 46–49), arguing that the cells undergoing fast versus slow cell division are qualitatively distinct.

The nature of the antigens that stimulate fast proliferation is an important issue. A clue to this problem was obtained by transferring naive CD4+ T lymphocytes to T and B lymphocyte-empty hosts raised in GF and, more recently, AF environments. The fast-dividing cells were partially and significantly reduced in GF and AF hosts although a residual fast population was reproducibly detected in these animals (26, 29, 31). A subsequent study showed that the fast population is divided into two sub-populations: commensal-bacteria-driven α 4β 7+ IL-17+ and commensal-bacteria-independent α 4β 7− IFN-γ + cells (42). Therefore, antigens derived from both commensal bacteria and self seem to contribute to fast proliferation in lymphopenic settings. Nevertheless, in non-lymphopenic, physiological settings, self-antigens appear to be sufficient for generation of the same response. This issue will be discussed further below.

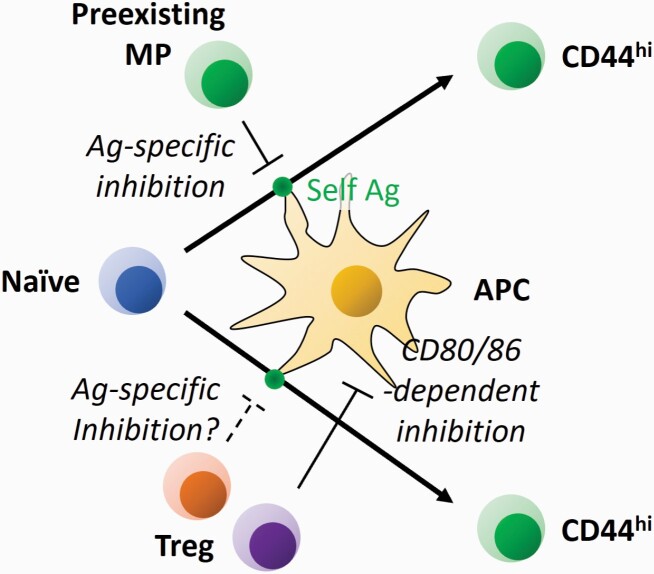

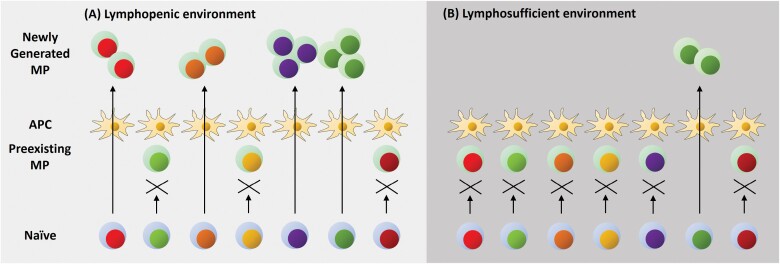

Interestingly, the ratio of slow versus fast proliferation is influenced by the type of lymphopenic host employed in these studies (27, 30, 33). Thus, in acutely and temporarily lymphopenic animals such as sub-lethally irradiated or CD90 monoclonal antibody-treated mice, slow division plays a dominant role in HP. On the other hand, in chronically lymphopenic animals such as Rag1/2, Tcra or Cd3e-deficient mice, fast proliferation is dominant. Two mutually non-exclusive explanations for this behavior seem likely. First, mucosal memory cells play important roles in host protection against intestinal microbes, and in the complete and chronic absence of T lymphocytes microbe-derived antigens and other components may leak into the body (1). Under such situations where abundant foreign antigens and co-stimulatory signals are present in the periphery, excess levels of fast proliferation may be induced. Second, fast proliferation may be induced to fill a ‘hole’ in the MP cell repertoire normally inhibited by pre-existing MP cells with the same TCR specificity (Figs 3 and 4) (50). This outcome may be achieved at least in part through an IL-27-dependent mechanism, where a pre-existing MP cell with a given specificity induces IL-27 on a CD8α-expressing type 1 DC (DC1) presenting its cognate antigen and renders the same DC unable to activate naive cells recognizing antigens on that DC (51). In addition, Treg cells can also inhibit fast proliferation (Fig. 3) (31, 46–48, 52). Indeed, Treg cells have been shown to remove the complex of antigen and MHC II from the surface of DCs to reduce their capacity for antigen presentation (53), possibly inhibiting fast proliferation of naive cells with the same TCR specificity. Treg cells are also known to inhibit CD80/CD86 expression by DCs (31, 54) and this can inhibit rapid proliferation in an antigen-unspecific manner. On the basis of the above considerations, in irradiated or other transiently lymphopenic animals where a residual fraction of host-derived T lymphocytes is present, these pre-existing MP and/or Treg cells may inhibit fast proliferation.

Fig. 3.

Regulation of fast HP of naive CD4+ T cells by pre-existing T lymphocytes. When naive CD4+ T lymphocytes in the periphery recognize available antigen (Ag) presented on APCs including DCs, they proliferate to acquire a CD44hi CD62Llo phenotype. This response can be inhibited by pre-existing MP cells with the same TCR specificity in an IL-27-dependent manner. In addition, the same pathway can be repressed by Treg cells in a CD80/CD86-dependent and possibly in an antigen-specific manner.

Fig. 4.

MP cell generation occurs in lymphopenic as well as lymphosufficient environments. (A) In an acutely and partially lymphopenic setting, naive precursors can give rise to MP cells upon recognition of antigens presented on APCs. In some cases when the antigens are occupied by pre-existing T lymphocytes with the same TCR specificity, this activation pathway is inhibited. (B) In a lymphosufficient condition, the above activation pathway generating MP cells is dampened to a significant degree because of antigen-occupying MP cells. However, sometimes a hole in the repertoire of MP cells appears since they exhibit rapid turnover. When this occurs, a naive precursor that can recognize the exposed antigen can rapidly proliferate to generate a new MP clone. Blue and green coloring of the cytosol represents naive and MP cells, respectively, whereas the different colors in nuclei indicate different TCR specificities.

This discussion raises the important issue of whether or not HP occurs under physiological conditions. Two early studies showed that newborn mice are lymphopenic and that the neonatal environment supports lymphopenia-induced HP in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (55, 56). More recently, we and other groups showed that the same proliferative response by CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes occurs even in lymphocompetent adult mice, although at a slower rate than in lymphopenic animals (2, 23). Thus, when naive CD4+ T lymphocytes are transferred into congenic, lymphosufficient mice, some donor cells rapidly proliferate to acquire an MP in a TCR and CD28 signaling-dependent manner. Because this fast proliferation or MP acquisition does not require stimulation with foreign antigens, the resultant cells are thought to be self-antigen-dependent rather than foreign-antigen-dependent MP cells although a minor contribution of commensal antigens and/or food antigens in these responses cannot be ruled out. This notion is further supported by the previously mentioned finding that CD5hi naive cells generate more MP cells than do their CD5lo counterparts for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

The fact that fast-dividing cells generated in lymphoreplete conditions are less prominent than those arising in lymphopenic settings may be due to pre-formed MP and/or Treg cells present in lymphoreplete, adult animals that can directly or indirectly inhibit fast proliferation as described above. Nevertheless, the ‘gate’ allowing the transition from naive to MP cells appears to remain open in lymphosufficient conditions (Fig. 4). On the basis of this cumulative evidence, we propose that fast proliferation of naive CD4+ as well as CD8+ T lymphocytes is a process occurring under both physiologic and lymphopenic conditions and is essential for generation of MP T cells.

Role of proliferation in MP cell maintenance

When transferred into lymphopenic hosts, MP cells themselves exhibit HP and this response is thought to be the major mechanism responsible for their maintenance. In the case of CD4+ MP cells, they give rise to both slowly and fast-dividing populations. The slow cell division is dependent on IL-7 but not MHC II (25, 32) and this response generates IFN-γ-producing MP cells (57). On the other hand, fast proliferation requires antigen stimulation as well as co-stimulation provided by DCs and generates IL-17-producing cells (25, 41, 57). This suggests heterogeneity of CD4+ MP cells in terms of maintenance, which is in contrast to CD8+ MP cells where fast proliferation is largely absent (32). The mechanistic basis of this distinction is unclear but may reflect a difference in TCR affinity to self-antigens in CD4+ versus CD8+ T lymphocytes. Indeed, CD4+ T lymphocytes are reported to have higher CD5 levels than CD8+ T cells (58), supporting this hypothesis.

Consistent with the above observations in lymphopenic environments, CD4+ MP cells are also known to be maintained in at least two distinct forms in the steady state, consisting of proliferating Ki67+ and quiescent Ki67− sub-populations (14, 25). Whether these Ki67+ and Ki67− cells are maintained as fast and slowly dividing cells by mechanisms analogous to those observed under lymphopenic settings is unclear. Interestingly, however, proliferation of the former sub-population has been shown to be heavily dependent on CD28 co-stimulation (2). This suggests that at least a portion of tonically dividing MP cells are maintained in a similar manner to the fast HP seen in lymphopenic settings.

Steady-state differentiation of MP cells and its functional significance

In the case of conventional CD4+ T lymphocytes, upon recognition of foreign antigen, naive CD4+ T cells differentiate into distinct subsets including Th1, Th2 and Th17. This fate decision is mainly, if not exclusively, made by environmental cues from cytokines (59). Thus, in the presence of IL-12, naive precursors differentiate into IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells, whereas under the influence of IL-4 they become Th2 cells. Similarly, Th17 cells are driven by IL-6 and TGF-β. Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells express master transcriptional factors T-bet, Gata3 and RORγt, respectively, which define their cytokine responsiveness. Specifically, upon foreign antigen recognition, Th1 cells respond to IL-12/IL-18 to produce IFN-γ, whereas Th2 cells are driven to express IL-4/IL-5/IL-13 by TSLP and IL-33. Th17 cells produce IL-17A in response to IL-23/IL-1.

In lymphopenia-induced HP, many previous reports have shown that rapidly but not slowly proliferating cells in the spleen produce IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 when stimulated ex vivo (29, 30, 37, 47, 56), suggesting that fast proliferation generates a predominantly Th1 response. In addition, a minor fraction in the fast population can produce IL-17, and this IL-17+ sub-population is more profound in gut-associated lymphoid tissues (42). As expected, when commensal bacteria are deleted by antibiotic treatment, the IL-17-producing population (marked by α 4β 7) is significantly reduced, whereas the IFN-γ + population remains largely intact. This finding strongly suggests that lymphopenia-driven, self-antigen-directed fast proliferation promotes a Th1-like cytokine expression profile.

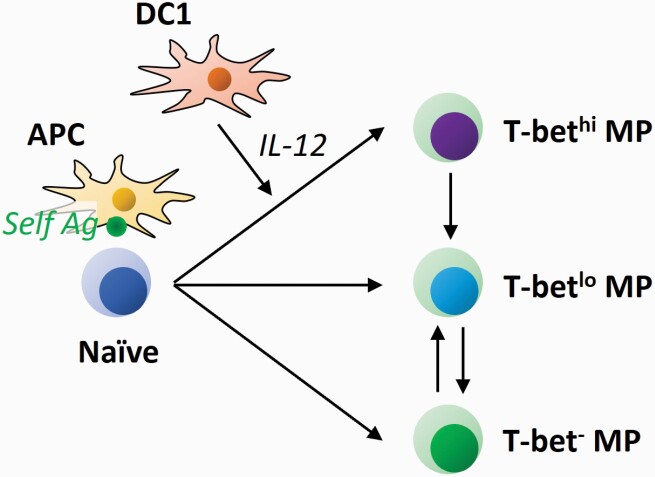

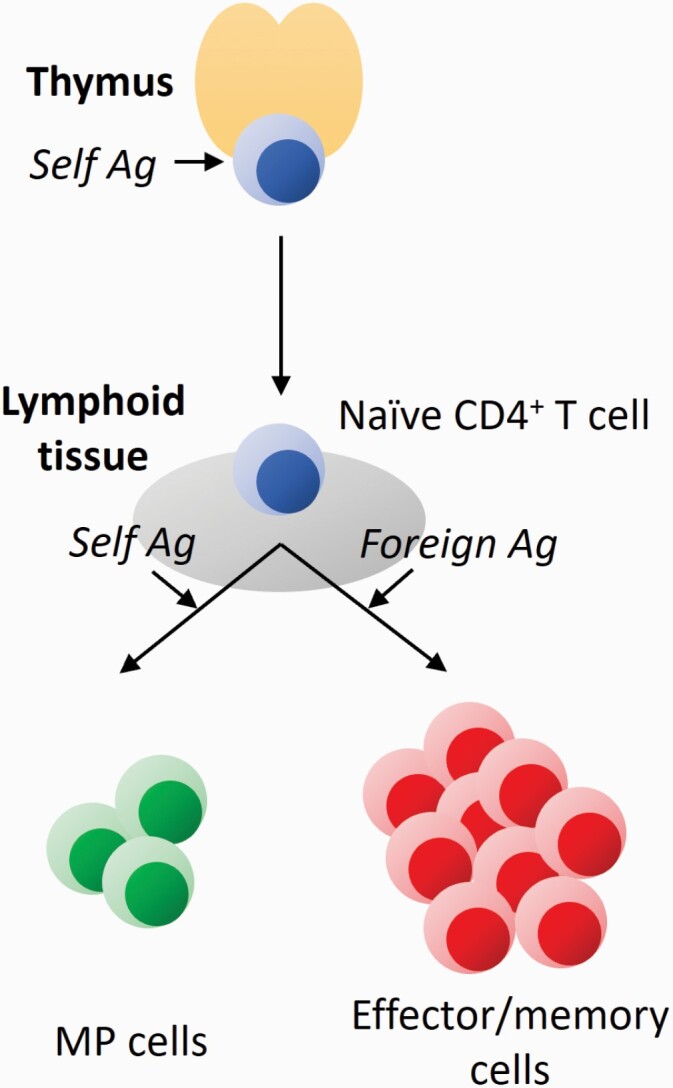

Under steady-state conditions, more than a half of MP CD4+ T lymphocytes tonically express T-bet and this T-bet+ sub-population can produce IFN-γ when appropriately stimulated (2). This fraction is equally present in SPF, GF and AF environments (3), supporting the above notion that self-directed responses drive a Th1-type differentiation. Intriguingly, this T-bet+ ‘MP1’ population consists of T-bethi and T-betlo fractions, and their homeostasis is dynamically maintained in the steady state (Fig. 5) (3). Thus, naive CD4+ T cells can homeostatically generate T-bethi, T-betlo and T-bet− MP cells. Whereas T-bet+ MP cells gradually decrease their T-bet expression with time, their T-bet− counterparts only give rise to T-betlo but not T-bethi cells. Given that T-bethi cells are homeostatically maintained throughout an animal’s life, we speculate that the window for their generation from naive precursors is likely to be very brief.

Fig. 5.

Tonic differentiation of MP CD4+ T lymphocytes. Naive CD4+ T cells recognize cognate self-antigen (Ag) on APCs to convert to MP cells. Under the influence of IL-12 that is homeostatically produced by DC1s, the MP cells further differentiate into the T-bethi MP1 subset. In equilibrium, T-bet+ MP cells gradually decrease their T-bet levels; in addition, T-bet− MP cells can acquire a T-betlo but not a T-bethi phenotype.

IL-12 plays an essential role as a determining factor for T-bethi MP1 differentiation during homeostasis (Fig. 5) (3). Bioactive IL-12 appears to be tonically produced by DC1s at a minimal level and these DCs appear to be different from the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that drive the generation of MP cells themselves because MP cells arise normally in the absence of DC1s.

The homeostatic production of IL-12 by DC1s appears to be basally primed by TLR2, TLR7 and/or TLR9 signaling. Since this pathway is unaltered in GF and AF conditions, self-derived agonists are thought to be involved in its activation. Indeed, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), β-defensin, surfactant protein A and D, and serum amyloid A can bind to TLR2 (60–66), whereas single-strand RNA and IgG–chromatin complexes are known to activate TLR7 and TLR9, respectively (67, 68). Once MP cells are exposed to relatively high levels (but within the normal physiological range) of IL-12, T-bet expression initially induced by TCR and CD28 signaling in the steady state may be further up-regulated via a feed-forward loop of the T-bet pathway (2, 3, 69–71).

Importantly, we have demonstrated that once T-bethi MP1 cells fully develop, they can exert innate-like effector function. Thus, in Toxoplasma and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, MP1 cells produce IFN-γ in response to IL-12 in the absence of antigen recognition and further support later development of antigen-specific adaptive Th1 responses, contributing to host protection (2). In parallel, CD8+ TVM cells can exert a similar innate-like effector function dependent on IL-15 (23), a finding that is in line with previous reports showing that antigen-specific conventional CD8+ memory cells can provide bystander host protection (72–75). We therefore have proposed that CD4+ and CD8+ MP cells contribute to the innate immune layer of protection mediated by NK cells and ILCs. The division of labor among these cell populations is currently unclear and needs further investigation.

It is unclear whether self-driven type 2 and/or type 17 MP lymphocytes also exist. In this regard, we previously showed that MP cells express some Th2- and Th17-associated genes at the mRNA level (2). Consistent with this observation, we have also detected small populations of IL-13+ as well as IL-17+ cells among MP CD4+ T lymphocytes when appropriately stimulated in vitro (T. Kawabe, unpublished observation). Given that foreign-antigen-specific Th2 cells can exert bystander effector function (76), it is possible that these hypothetical ‘MP2’ and/or ‘MP17’ cells have similar innate immune activity.

It is important to note that CD8+ TVM cells have been shown to exert adaptive immune responses as well. Specifically, TCR-transgenic CD8+ MP cells generated in lymphopenic mice provide antigen-specific protection (77). By the same token, TVM cells defined by tetramer staining rapidly respond to antigen stimulation (20). Moreover, although the antigen-specific response by TVM cells is weaker than that by antigen-driven memory cells, the former generates central memory cells, thereby leading to efficient pathogen control (24). Together these observations support the hypothesis that ‘pre-immune’ CD8+ T lymphocytes with an MP can provide antigen-specific immune responses. Whether this concept applies to CD4+ MP cells is unclear and needs further investigation (78).

Conclusions

Although the CD44hi CD62Llo CD4+ T lymphocytes that are present in unimmunized normal mice were presumed to all represent foreign-antigen-specific conventional memory cells in the past, it is now clear that such ‘MP cells’ are different from the latter population in several respects. Thus, MP cells are generated from peripheral naive precursors via recognition of self-antigens and further differentiate into T-bet+ ‘MP1’ cells in the presence of DC1-derived IL-12 in the steady state. These MP1 cells can exert innate-like effector function by responding to augmented levels of IL-12 in the absence of foreign-antigen recognition to produce IFN-γ thereby contributing to host protection. On the basis of these observations, we propose the concept that homeostatic generation, proliferation and differentiation of CD4+ as well as CD8+ T lymphocytes that are driven by self-derived rather than foreign-derived agonists are defining features of innate-like MP as compared with conventional memory T lymphocytes.

Despite significant advances in this field, many questions remain to be answered. First, phenotypic markers or transcription factors defining MP CD4+ T cells have not been established. Because the pathways of their development and maintenance are distinct from conventional, foreign-antigen-specific memory cells, MP cells should possess unique phenotypic features. In this regard, we have identified several cell-surface as well as intracellular proteins differentially expressed in MP versus conventional memory cells (T. Kawabe, manuscript submitted). If these molecules can be confirmed as markers that distinguish these two populations, it will enable us to specifically delete MP cells to directly test their physiological significance in mice.

Second, MP cells in humans have not been identified although a cell population with rapid turnover that develops in the absence of foreign antigens has been observed in human cord blood and the fetus (16, 17). If human MP cell markers become available, it will be important to investigate the phenotypic characteristics as well as function of these MP-like cells.

Lastly, given the self-specificity of MP cells, consideration should be given to their possible contribution to autoimmune or inflammatory pathology. Our recent observations suggest that MP1 cells can induce inflammation in the absence of Treg cells (T. Kawabe, unpublished observation). If such a role can be confirmed at a broader level, inhibition of MP cell generation, proliferation, differentiation and/or effector function could serve as a therapeutic strategy for patients suffering from these conditions.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the late W. E. Paul and C. D. Surh for their invaluable contributions to this field. We also thank J. Sprent for thoughtful discussions as well as N. Ishii for his critical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (T.K.) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (A.S.).

Conflicts of interest statement: the authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Kawabe, T., Yi, J. and Sprent, J. 2021. Homeostasis of naive and memory T lymphocytes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 13:a037879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kawabe, T., Jankovic, D., Kawabe, S.et al. 2017. Memory-phenotype CD4(+) T cells spontaneously generated under steady-state conditions exert innate TH1-like effector function. Sci. Immunol. 2:eaam9304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kawabe, T., Yi, J., Kawajiri, A.et al. 2020. Requirements for the differentiation of innate T-bethigh memory-phenotype CD4+ T lymphocytes under steady state. Nat. Commun. 11:3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Artis, D. and Spits, H. 2015. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature 517:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. White, J. T., Cross, E. W. and Kedl, R. M. 2017. Antigen-inexperienced memory CD8+ T cells: where they come from and why we need them. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17:391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawabe, T., Zhu, J. and Sher, A. 2018. Foreign antigen-independent memory-phenotype CD4+ T cells: a new player in innate immunity? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pereira, P., Forni, L., Larsson, E. L.et al. 1986. Autonomous activation of B and T cells in antigen-free mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 16:685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dobber, R., Hertogh-Huijbregts, A., Rozing, J.et al. 1992. The involvement of the intestinal microflora in the expansion of CD4+ T cells with a naive phenotype in the periphery. Dev. Immunol. 2:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim, K. S., Hong, S. W., Han, D.et al. 2016. Dietary antigens limit mucosal immunity by inducing regulatory T cells in the small intestine. Science 351:858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vrisekoop, N., Artusa, P., Monteiro, J. P.et al. 2017. Weakly self-reactive T-cell clones can homeostatically expand when present at low numbers. Eur. J. Immunol. 47:68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mandl, J. N., Monteiro, J. P., Vrisekoop, N.et al. 2013. T cell-positive selection uses self-ligand binding strength to optimize repertoire recognition of foreign antigens. Immunity 38:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klein, L., Kyewski, B., Allen, P. M.et al. 2014. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don’t see). Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lenz, D. C., Kurz, S. K., Lemmens, E.et al. 2004. IL-7 regulates basal homeostatic proliferation of antiviral CD4+ T cell memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101:9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Younes, S. A., Punkosdy, G., Caucheteux, S.et al. 2011. Memory phenotype CD4 T cells undergoing rapid, nonburst-like, cytokine-driven proliferation can be distinguished from antigen-experienced memory cells. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tough, D. F. and Sprent, J. 1994. Turnover of naive- and memory-phenotype T cells. J. Exp. Med. 179:1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Byrne, J. A., Stankovic, A. K. and Cooper, M. D. 1994. A novel subpopulation of primed T cells in the human fetus. J. Immunol. 152:3098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szabolcs, P., Park, K. D., Reese, M.et al. 2003. Coexistent naïve phenotype and higher cycling rate of cord blood T cells as compared to adult peripheral blood. Exp. Hematol. 31:708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Atherly, L. O., Lucas, J. A., Felices, M.et al. 2006. The Tec family tyrosine kinases Itk and Rlk regulate the development of conventional CD8+ T cells. Immunity 25:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Broussard, C., Fleischacker, C., Fleischecker, C.et al. 2006. Altered development of CD8+ T cell lineages in mice deficient for the Tec kinases Itk and Rlk. Immunity 25:93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haluszczak, C., Akue, A. D., Hamilton, S. E.et al. 2009. The antigen-specific CD8+ T cell repertoire in unimmunized mice includes memory phenotype cells bearing markers of homeostatic expansion. J. Exp. Med. 206:435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weinreich, M. A., Odumade, O. A., Jameson, S. C.et al. 2010. T cells expressing the transcription factor PLZF regulate the development of memory-like CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 11:709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kennedy, M. K., Glaccum, M., Brown, S. N.et al. 2000. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 191:771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. White, J. T., Cross, E. W., Burchill, M. A.et al. 2016. Virtual memory T cells develop and mediate bystander protective immunity in an IL-15-dependent manner. Nat. Commun. 7:11291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee, J. Y., Hamilton, S. E., Akue, A. D.et al. 2013. Virtual memory CD8 T cells display unique functional properties. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110:13498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purton, J. F., Tan, J. T., Rubinstein, M. P.et al. 2007. Antiviral CD4+ memory T cells are IL-15 dependent. J. Exp. Med. 204:951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martin, C. E., Spasova, D. S., Frimpong-Boateng, K.et al. 2017. Interleukin-7 availability is maintained by a hematopoietic cytokine sink comprising innate lymphoid cells and t cells. Immunity 47:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ernst, B., Lee, D. S., Chang, J. M.et al. 1999. The peptide ligands mediating positive selection in the thymus control T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery. Immunity 11:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Viret, C., Wong, F. S. and Janeway, C. A., Jr. 1999. Designing and maintaining the mature TCR repertoire: the continuum of self-peptide:self-MHC complex recognition. Immunity 10:559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kieper, W. C., Troy, A., Burghardt, J. T.et al. 2005. Recent immune status determines the source of antigens that drive homeostatic T cell expansion. J. Immunol. 174:3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Min, B., Yamane, H., Hu-Li, J.et al. 2005. Spontaneous and homeostatic proliferation of CD4 T cells are regulated by different mechanisms. J. Immunol. 174:6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yi, J., Jung, J., Hong, S. W.et al. 2019. Unregulated antigen-presenting cell activation by T cells breaks self tolerance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tan, J. T., Ernst, B., Kieper, W. C.et al. 2002. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7 jointly regulate homeostatic proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells but are not required for memory phenotype CD4+ cells. J. Exp. Med. 195:1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin, B., Bourgeois, C., Dautigny, N.et al. 2003. On the role of MHC class II molecules in the survival and lymphopenia-induced proliferation of peripheral CD4+ T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100:6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kassiotis, G., Zamoyska, R. and Stockinger, B. 2003. Involvement of avidity for major histocompatibility complex in homeostasis of naive and memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 197:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan, J. T., Dudl, E., LeRoy, E.et al. 2001. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98:8732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Becklund, B. R., Purton, J. F., Ramsey, C.et al. 2016. The aged lymphoid tissue environment fails to support naïve T cell homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 6:30842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gudmundsdottir, H. and Turka, L. A. 2001. A closer look at homeostatic proliferation of CD4+ T cells: costimulatory requirements and role in memory formation. J. Immunol. 167:3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Prlic, M., Blazar, B. R., Khoruts, A.et al. 2001. Homeostatic expansion occurs independently of costimulatory signals. J. Immunol. 167:5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McHugh, R. S. and Shevach, E. M. 2002. Cutting edge: depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is necessary, but not sufficient, for induction of organ-specific autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 168:5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hagen, K. A., Moses, C. T., Drasler, E. F.et al. 2004. A role for CD28 in lymphopenia-induced proliferation of CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 173:3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Do, J. S. and Min, B. 2009. Differential requirements of MHC and of DCs for endogenous proliferation of different T-cell subsets in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106:20394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kawabe, T., Sun, S. L., Fujita, T.et al. 2013. Homeostatic proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes generates gut-tropic Th17 cells. J. Immunol. 190:5788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cho, J. H., Boyman, O., Kim, H. O.et al. 2007. An intense form of homeostatic proliferation of naive CD8+ cells driven by IL-2. J. Exp. Med. 204:1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramsey, C., Rubinstein, M. P., Kim, D. M.et al. 2008. The lymphopenic environment of CD132 (common gamma-chain)-deficient hosts elicits rapid homeostatic proliferation of naive T cells via IL-15. J. Immunol. 180:5320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cho, J. H., Kim, H. O., Surh, C. D.et al. 2010. T cell receptor-dependent regulation of lipid rafts controls naive CD8+ T cell homeostasis. Immunity 32:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bourgeois, C. and Stockinger, B. 2006. CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells and memory T cells prevent lymphopenia-induced proliferation of naive T cells in transient states of lymphopenia. J. Immunol. 177:4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Winstead, C. J., Fraser, J. M. and Khoruts, A. 2008. Regulatory CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells selectively inhibit the spontaneous form of lymphopenia-induced proliferation of naive T cells. J. Immunol. 180:7305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bolton, H. A., Zhu, E., Terry, A. M.et al. 2015. Selective Treg reconstitution during lymphopenia normalizes DC costimulation and prevents graft-versus-host disease. J. Clin. Invest. 125:3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang, N. and Bevan, M. J. 2012. TGF-β signaling to T cells inhibits autoimmunity during lymphopenia-driven proliferation. Nat. Immunol. 13:667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Min, B., Foucras, G., Meier-Schellersheim, M.et al. 2004. Spontaneous proliferation, a response of naive CD4 T cells determined by the diversity of the memory cell repertoire. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101:3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Do, J. S., Visperas, A., Oh, K.et al. 2012. Memory CD4 T cells induce selective expression of IL-27 in CD8+ dendritic cells and regulate homeostatic naive T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 188:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yi, J., Kawabe, T. and Sprent, J. 2020. New insights on T-cell self-tolerance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 63:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Akkaya, B., Oya, Y., Akkaya, M.et al. 2019. Regulatory T cells mediate specific suppression by depleting peptide-MHC class II from dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 20:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim, J. M., Rasmussen, J. P. and Rudensky, A. Y. 2007. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat. Immunol. 8:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ichii, H., Sakamoto, A., Hatano, M.et al. 2002. Role for Bcl-6 in the generation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 3:558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Min, B., McHugh, R., Sempowski, G. D.et al. 2003. Neonates support lymphopenia-induced proliferation. Immunity 18:131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yamaki, S., Ine, S., Kawabe, T.et al. 2014. OX40 and IL-7 play synergistic roles in the homeostatic proliferation of effector memory CD4+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 44:3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matson, C. A., Choi, S., Livak, F.et al. 2020. CD5 dynamically calibrates basal NF-κB signaling in T cells during thymic development and peripheral activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117:14342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhu, J., Yamane, H. and Paul, W. E. 2010. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murakami, S., Iwaki, D., Mitsuzawa, H.et al. 2002. Surfactant protein A inhibits peptidoglycan-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion in U937 cells and alveolar macrophages by direct interaction with toll-like receptor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 277:6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Park, J. S., Svetkauskaite, D., He, Q.et al. 2004. Involvement of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279:7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ohya, M., Nishitani, C., Sano, H.et al. 2006. Human pulmonary surfactant protein D binds the extracellular domains of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 through the carbohydrate recognition domain by a mechanism different from its binding to phosphatidylinositol and lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry 45:8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Park, J. S., Gamboni-Robertson, F., He, Q.et al. 2006. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290:C917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Funderburg, N., Lederman, M. M., Feng, Z.et al. 2007. Human -defensin-3 activates professional antigen-presenting cells via Toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104:18631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cheng, N., He, R., Tian, J.et al. 2008. Cutting edge: TLR2 is a functional receptor for acute-phase serum amyloid A. J. Immunol. 181:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. He, R. L., Zhou, J., Hanson, C. Z.et al. 2009. Serum amyloid A induces G-CSF expression and neutrophilia via Toll-like receptor 2. Blood 113:429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Leadbetter, E. A., Rifkin, I. R., Hohlbaum, A. M.et al. 2002. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature 416:603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vollmer, J., Tluk, S., Schmitz, C.et al. 2005. Immune stimulation mediated by autoantigen binding sites within small nuclear RNAs involves Toll-like receptors 7 and 8. J. Exp. Med. 202:1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mullen, A. C., High, F. A., Hutchins, A. S.et al. 2001. Role of T-bet in commitment of TH1 cells before IL-12-dependent selection. Science 292:1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Afkarian, M., Sedy, J. R., Yang, J.et al. 2002. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naïve CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 3:549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhu, J., Jankovic, D., Oler, A. J.et al. 2012. The transcription factor T-bet is induced by multiple pathways and prevents an endogenous Th2 cell program during Th1 cell responses. Immunity 37:660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Berg, R. E., Crossley, E., Murray, S.et al. 2003. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J. Exp. Med. 198:1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Soudja, S. M., Ruiz, A. L., Marie, J. C.et al. 2012. Inflammatory monocytes activate memory CD8(+) T and innate NK lymphocytes independent of cognate antigen during microbial pathogen invasion. Immunity 37:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chu, T., Tyznik, A. J., Roepke, S.et al. 2013. Bystander-activated memory CD8 T cells control early pathogen load in an innate-like, NKG2D-dependent manner. Cell Rep. 3:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schenkel, J. M., Fraser, K. A., Beura, L. K.et al. 2014. T cell memory. Resident memory CD8 T cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science 346:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Guo, L., Huang, Y., Chen, X.et al. 2015. Innate immunological function of TH2 cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 16:1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hamilton, S. E., Wolkers, M. C., Schoenberger, S. P.et al. 2006. The generation of protective memory-like CD8+ T cells during homeostatic proliferation requires CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 7:475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kawabe, T., Suzuki, N., Yamaki, S.et al. 2016. Mesenteric lymph nodes contribute to proinflammatory Th17-cell generation during inflammation of the small intestine in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 46:1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]