Abstract

Background/Aim

To clarify the clinical significance of the absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPI) treatment in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.

Patients and Methods

We performed a retrospective study, by reviewing the medical charts of 191 patients who were treated with ICPI monotherapy and 80 patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy during the period from February 2016 and April 2021.

Results

In patients treated with ICPI monotherapy, there was a significant difference in time to treatment failure (TTF) between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥ or <10%. Similarly, a significant difference was found in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥ or <1,500/μl. Factors related to both an increase in the number and percentage of peripheral eosinophils were "immune-related adverse effects (irAE) that did not lead to discontinuation of administration".

Conclusion

Some patients with irAE might have a 'favorable' absolute increase in peripheral eosinophils.

Keywords: Peripheral eosinophils, immune checkpoint inhibitor, non-small cell lung cancer patients, logistic regression analysis

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPIs), which can significantly contribute to prolonging survival, has revolutionized the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (1,2). However, researches on biomarkers of ICPIs that can predict therapeutic efficacy and duration of response have been delayed, and there is insufficient information on the selection of patients who will benefit from the treatment. Currently, programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) is used to predict the therapeutic effect of ICPIs. However, this indicator is not sufficient for assaying therapeutic efficacy (3,4). Therefore, research has focused on the identification of novel biomarkers and the predictive role of changes in peripheral blood cells has been examined (5-18). In most of the patients treated with ICPI, the fluctuation of peripheral eosinophils seemed to be relative to other leukocyte components (5,7,9,15,16). The role of eosinophils in cancer immunity is still under investigation (17-22). Furthermore, the biological and clinical significance of the increase in the absolute number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils with ICPI therapy is unknown. Although very rare, however, in clinical practice, there are patients who develop a significant increase in the absolute number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils with ICPI therapy. The response to ICPI treatment in these patients is also unclear. A retrospective study was conducted with the aim of clarifying the presence of these patients and their response to ICPI treatment. There are several definitions of eosinophilia (23-25). However, there is no definition of the absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils in ICPI treatment. In our previous study using the receiver operation curve analysis, 5% was an appropriate cutoff value (26). The absolute increase in the proportion of peripheral eosinophils in this study was set at 10%, which indicated twice the cutoff value determined in our previous study. With regard to the absolute increase in the number of peripheral eosinophils, we set 1500/μl as cutoff value with reference to the diagnostic criteria for hypereosinophilic syndrome (25).

Patients and Methods

Patients. We analyzed the medical records of all patients diagnosed with NSCLC in three tertiary hospitals in Japan (Mito Medical Center, University of Tsukuba–Mito Kyodo General Hospital, Ryugasaki Saiseikai Hospital, and Tsukuba University Hospital) between February 2016 and April 2021. Patients with NSCLC treated with ICPI monotherapy or combination of ICPI and chemotherapy during this period were included. NSCLC was diagnosed based on the World Health Organization classification. Tumor node metastasis staging (TNM Classification, 8th Edition) was performed in all patients prior to ICPI therapy initiation using head computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, bone scans, and ultrasonography and/or computed tomography of the abdomen. Patients with the following comorbidities and with a history of treatment for these conditions were excluded; parasitic infestations, allergic diseases, auto immune diseases and hematologic malignancies. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and those with bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap requiring systemic steroid use were also excluded. Particular attention was paid to adrenal insufficiency as an immune related adverse event (irAE). Patients who developed eosinophilia associated with adrenal insufficiency as an irAE were excluded from this study. Patient demographic data, including age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score for performance status (PS), histopathology, disease stage, PD-L1 expression, objective tumor response, and survival, were obtained from the patients’ medical charts. Tumor response was evaluated as complete response, partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (Version 1.1).

Peripheral eosinophil count and percentage measurement. Eosinophil counts and percentages were measured at the same time as complete blood count measurements before and during ICPI therapy. Results were obtained from the medical records of each patient. Counts for leukocyte subpopulations were measured by routine clinical laboratory analysis using a Sysmex XN 3000 analyzer (Sysmex Co., Ltd. Kobe, Japan). With reference to previous studies (25,26), the cut-off value for the absolute increase in proportion of peripheral eosinophils was set to 10%. The absolute increase in the number of peripheral eosinophils was set to 1500/μl or more.

Statistical analysis. The χ2 test was used to compare nominal variables. We used the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test to compare values with unknown population variance. By univariate analysis, we investigated the association between patient background factors (gender, PS, age, pathology, stage, driver genes, PD-L1, and irAE) and time to treatment failure (TTF). We adopted the definition of TTF that is commonly used in cancer treatment; the interval from initiation of therapy with ICPIs to treatment discontinuation or the last follow up visit. TTF was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log rank test. Logistic regression analysis was used for statistical analysis. ‘Eosinophils≥10%’ or ‘eosinophils ≥1,500/μl’ was selected as the objective variable and the other background factors were considered as independent variables. p-Values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics. This study conformed to the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Studies issued by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan. Written informed consent for a non-interventional retrospective study was obtained from each patient. The analysis of the medical records of patients with lung cancer was approved by the ethics committee of Mito Medical Center–University of Tsukuba Hospital (NO 20-57).

Results

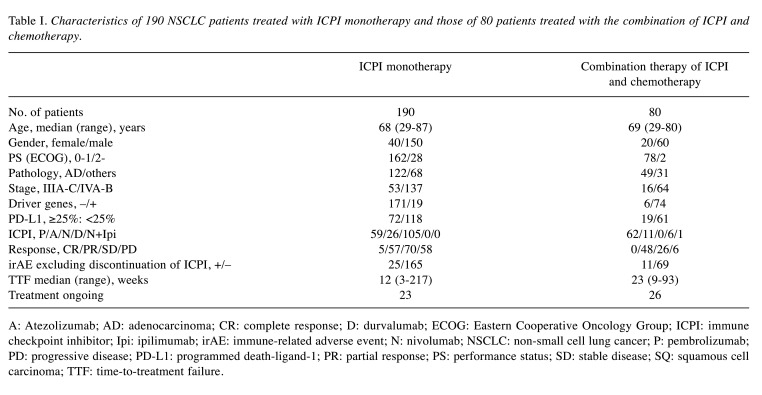

Characteristics of patients. Table I and Table II show the characteristics of patients treated with ICPI monotherapy and those of patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy. In 190 patients treated with ICPI monotherapy, 8 (4.2%) had eosinophils ≥10% and 30 (15.8%) had eosinophils ≥1,500/μl. Median (range) of TTF in these patients were 30 weeks (median=6-217 weeks) and 75 weeks (range=35-217 weeks), respectively. In 80 patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy, 3 (3.8%) had eosinophils ≥10% and 14 (17.5%) had eosinophils ≥1,500/μl. Median (range=35-217 weeks) of TTF in these patients were 30 weeks (median=24-75 weeks) and 36 weeks (range=6-75 weeks), respectively.

Table I. Characteristics of 190 NSCLC patients treated with ICPI monotherapy and those of 80 patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy.

A: Atezolizumab; AD: adenocarcinoma; CR: complete response; D: durvalumab; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICPI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; Ipi: ipilimumab; irAE: immune-related adverse event; N: nivolumab; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; P: pembrolizumab; PD: progressive disease; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand-1; PR: partial response; PS: performance status; SD: stable disease; SQ: squamous cell carcinoma; TTF: time-to-treatment failure.

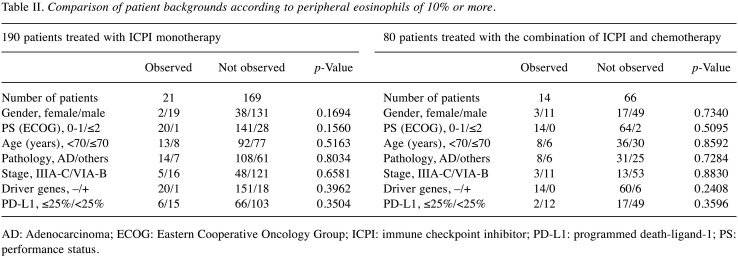

Table II. Comparison of patient backgrounds according to peripheral eosinophils of 10% or more.

AD: Adenocarcinoma; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICPI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand-1; PS: performance status.

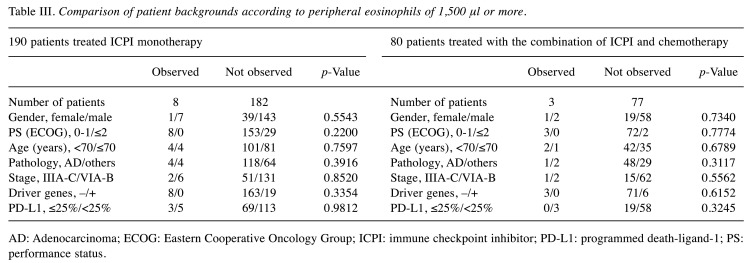

Table III and Table IV show the comparison of patients’ eosinophils ≥ or <10%, and that of eosinophils ≥ or <1,500/μl in both treatment groups. There were no statistical ly significant differences in patient background factors before treatment in both treatment groups.

Table III. Comparison of patient backgrounds according to peripheral eosinophils of 1,500 μl or more.

AD: Adenocarcinoma; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICPI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand-1; PS: performance status.

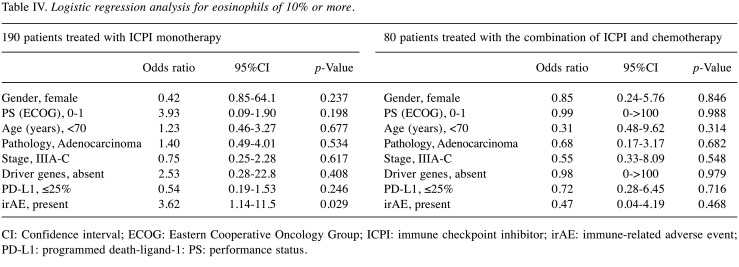

Table IV. Logistic regression analysis for eosinophils of 10% or more.

CI: Confidence interval; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICPI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; irAE: immune-related adverse event; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand-1: PS: performance status.

TTF in patients with eosinophils ≥10% and those with eosinophils ≥1,500/μl. In patients treated with ICPI monotherapy, there was a significant difference in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥ or <10% (p=0.0038). Similarly, a significant difference was found in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥ or <1,500/μl (p=0.0023). In patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy, there was no significant difference in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥ or <10% (p=0.2740). No significant difference was found in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥ or <1,500/μl (p=0.7574).

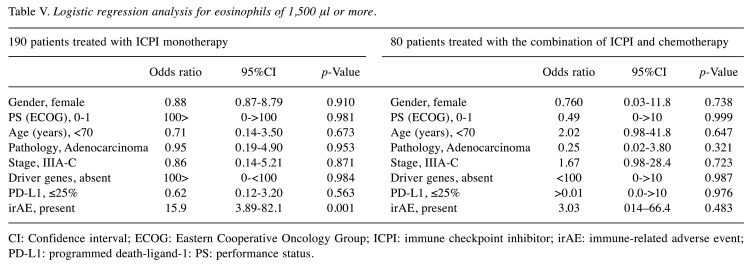

Factors associated with eosinophils ≥ 10% and eosinophils ≥1500/μl. Table IV and Table V show the results of logistic regression analysis in patients treated with ICPI monotherapy. In this analysis, there was no association of pretreatment background factors with ‘eosinophils ≥10%’. Furthermore, no pretreatment background factors associated with ‘eosinophils ≥1500/μl’. The appearance of irAE was associated with both ‘eosinophils ≥10%’ and ‘eosinophils ≥1,500/μl’ (p=0.029 and 0.001, respectively). In patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy, there were no pretreatment and treatment-related factors that were associated with ‘eosinophils ≥10%’. No such factor was found to be associated with ‘eosinophils ≥1,500/μl’ (Table IV and Table V).

Table V. Logistic regression analysis for eosinophils of 1,500 μl or more.

CI: Confidence interval; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICPI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; irAE: immune-related adverse event; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand-1: PS: performance status.

Discussion

There have been several studies mainly examining lymphocytes and eosinophils as biomarkers for ICPI therapy (5-18). Peripheral eosinophils are of interest although their involvement in cancer immunity remains unclear (5,7,9,15,16). We have also performed a few studies on this subject (26-28). In not a few patients, the relative increase rate of eosinophils due to fluctuations in other leukocyte components might be conceivable (5,7,9,15,16). However, with ICPI therapy, in clinical practice, although rare, there were patients who developed an absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils. Since there is need to provide medical care for these patients, we decided to carry out this study. We asked the following questions: how many patients had absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils? What were the characteristics of these patients? Was there TTF prolongation, and were there any factors associated with TTF prolongation? What were the patient background factors associated with the absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils? The purpose of this study was to obtain information to answer these questions.

In patients treated with ICPI monotherapy, the following four important results were obtained. 1) There were patients whose ≥10% or ≥1,500/μl eosinophils during the clinical courses. This might suggest that there were patients who had an absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils, rather than a relative increase. 2) There was no difference in patient background factors known before treatment between the two groups with eosinophils divided by ‘eosinophils ≥10%’ and between the two groups with eosinophils divided by ‘eosinophils ≥1,500/μl’. 3) There was a significant difference in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥10%. TTF was significantly different between the two groups divided by eosinophils 1,500/μl. 4) In the logistic analysis, there were no pretreatment background factors associated with ‘eosinophils ≥ 10%’. No pretreatment background factors were associated with ‘eosinophils ≥1,500/μl’. However, the appearance of irAE was associated with both ‘eosinophils ≥10%’ and ‘eosinophils ≥1500/μl’, although this was a factor that became apparent during the course of treatment.

In patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy, on the other hand, the following two results were obtained. 1) There were patients with eosinophils ≥10% and patients with eosinophils ≥1,500/μl during the clinical courses. 2) No difference was found in TTF between the two groups divided by eosinophils ≥10% and between those divided by eosinophils ≥1,500/μl. In the logistic analysis, there were no significant factors associated with ‘eosinophils ≥10%’. No factors were found to be significantly related to ‘eosinophils ≥1,500/μl’. The reason why no significant factor was found in patients treated with the combination of ICPI and chemotherapy was not clear. But it might be related to the small number of patients evaluated and the short follow-up period. However, it is estimated that there is a large influence of the cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs on peripheral white blood cells including eosinophils.

Although the above results are remarkable, there are certain limitations in this study. First, this study included patients from three tertiary hospitals, but their number was small. Second, this study included patients treated with any of the currently available ICPIs and also patients treated with various chemotherapy regimens. In addition, patients receiving ICPI treatment on any treatment line were included. It must be considered that the inclusion of various treatments affected the outcome. However, the information we want to obtain in the clinical setting might be more practical than the information we get in studies with strict selection criteria. Third, the validity of this research method of changing objective variables and repeating logistic analysis is questionable. Such limitations must be overcome in future studies.

Prior to ICPI therapy, finding factors associated with an absolute increase in the number and proportion of peripheral eosinophils is important in identifying biomarkers predicting long-term response of patients. Furthermore, it is important to explore the involvement of eosinophils in cancer immunity.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

HO and HS designed the study; SO, TS, KM, YS, GO, KK, SS, TK, and HS collected the data. HO, SO, KN, RN, HS and NH analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. All Authors approved the final version of the article.

References

- 1.Remon J, Passiglia F, Ahn MJ, Barlesi F, Forde PM, Garon EB, Gettinger S, Goldberg SB, Herbst RS, Horn L, Kubota K, Lu S, Mezquita L, Paz-Ares L, Popat S, Schalper KA, Skoulidis F, Reck M, Adjei AA, Scagliotti GV. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in thoracic malignancies: review of the existing evidence by an IASLC expert panel and recommendations. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(6):914–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiala O, Sorejs O, Sustr J, Kucera R, Topolcan O, Finek J. Immune-related adverse effects and outcome of patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(3):1219–1227. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantuejoul S, Sound-Tsao M, Cooper WA, Girard N, Hirsch FR, Roden AC, Lopez-Rios F, Jain D, Chou TY, Motoi N, Kerr KM, Yatabe Y, Brambilla E, Longshore J, Papotti M, Sholl LM, Thunnissen E, Rekhtman N, Borczuk A, Bubendorf L, Minami Y, Beasley MB, Botling J, Chen G, Chung JH, Dacic S, Hwang D, Lin D, Moreira A, Nicholson AG, Noguchi M, Pelosi G, Poleri C, Travis W, Yoshida A, Daigneault JB, Wistuba II, Mino-Kenudson M. PD-L1 testing for lung cancer in 2019: Perspective from the IASLC Pathology Committee. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(4):499–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams JB, Li S, Higgs EF, Cabanov A, Wang X, Huang H, Gajewski TF. Tumor heterogeneity and clonal cooperation influence the immune selection of IFN-γ-signaling mutant cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):602. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delyon J, Mateus C, Lefeuvre D, Lanoy E, Zitvogel L, Chaput N, Roy S, Eggermont AM, Routier E, Robert C. Experience in daily practice with ipilimumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: an early increase in lymphocyte and eosinophil counts is associated with improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(6):1697–1703. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubo S, Kobayashi N, Somekawa K, Hirata M, Kamimaki C, Aiko H, Katakura S, Teranishi S, Watanabe K, Hara YU, Yamamoto M, Kudo M, Kaneko T. Identification of biomarkers for non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3889–3896. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreira A, Leisgang W, Schuler G, Heinzerling L. Eosinophilic count as a biomarker for prognosis of melanoma patients and its importance in the response to immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9(2):115–121. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buder-Bakhaya K, Hassel JC. Biomarkers for clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment-a review from the melanoma perspective and beyond. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1474. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon SCS, Hu X, Panten J, Grees M, Renders S, Thomas D, Weber R, Schulze TJ, Utikal J, Umansky V. Eosinophil accumulation predicts response to melanoma treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1727116. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1727116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanizaki J, Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, Nakamura Y, Yonesaka K, Kudo K, Kaneda H, Hasegawa Y, Tanaka K, Takeda M, Ito A, Nakagawa K. Peripheral blood biomarkers associated with clinicaloutcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facchinetti F, Veneziani M, Buti S, Gelsomino F, Squadrilli A, Bordi P, Bersanelli M, Cosenza A, Ferri L, Rapacchi E, Mazzaschi G, Leonardi F, Quaini F, Ardizzoni A, Missale G, Tiseo M. Clinical and hematologic parameters address the outcomes of non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Immunotherapy. 2018;10(8):681–694. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsurada M, Nagano T, Tachihara M, Kiriu T, Furukawa K, Koyama K, Otoshi T, Sekiya R, Hazama D, Tamura D, Nakata K, Katsurada N, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi K, Nishimura Y. Baseline tumor size as a predictive and prognostic factor of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(2):815–825. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inomata M, Kado T, Okazawa S, Imanishi S, Taka C, Kambara K, Hirai T, Tanaka H, Tokui K, Hayashi K, Miwa T, Hayashi R, Matsui S, Tobe K. Peripheral PD1-positive CD4 T-lymphocyte count can predict progression-free survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(12):6887–6893. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soda H, Ogawara D, Fukuda Y, Tomono H, Okuno D, Koga S, Taniguchi H, Yoshida M, Harada T, Umemura A, Yamaguchi H, Mukae H. Dynamics of blood neutrophil-related indices during nivolumab treatment may be associated with response to salvage chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: A hypothesis-generating study. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10(2):341–346. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou Y, Marin-Acevedo JA, Vishnu P, Manochakian R, Dholaria B, Soyano A, Luo Y, Zhang Y, Knutson KL. Hypereosinophilia in a patient with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer treated with antiprogrammed cell death 1 (anti-PD-1) therapy. Immunotherapy. 2019;11(7):577–584. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alves A, Sucena I, Dias M, Coutinho D, Silva E, Costa T, Conde S, Barroso A, Campainha S. Eosinophilia in lung cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Lung cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2019.PA4664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh N, Lubana SS, Constantinou G, Leaf AN. Immunocheckpoint inhibitor- (Nivolumab-) associated hypereosinophilia in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2020;2020:7492634. doi: 10.1155/2020/7492634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hude I, Sasse S, Bröckelmann PJ, von Tresckow B, Momotow J, Engert A, Borchmann S. Leucocyte and eosinophil counts predict progression-free survival in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin Lymphoma patients treated with PD1 inhibition. Br J Haematol. 2018;181(6):837–840. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandit R, Scholnik A, Wulfekuhler L, Dimitrov N. Non-small-cell lung cancer associated with excessive eosinophilia and secretion of interleukin-5 as a paraneoplastic syndrome. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(3):234–237. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Osta H, El-Haddad P, Nabbout N. Lung carcinoma associated with excessive eosinophilia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3456–3457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rigoni A, Colombo MP, Pucillo C. Mast cells, basophils and eosinophils: From allergy to cancer. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon SCS, Utikal J, Umansky V. Opposing roles of eosinophils in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(5):823–833. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2255-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018(1):326–331. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF, Hellmann A, Metzgeroth G, Leiferman KM, Arock M, Butterfield JH, Sperr WR, Sotlar K, Vandenberghe P, Haferlach T, Simon HU, Reiter A, Gleich GJ. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):607–612.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okauchi S, Shiozawa T, Miyazaki K, Nishino K, Sasatani Y, Ohara G, Kagohashi K, Sato S, Kodama T, Satoh H, Hizawa N. Association between peripheral eosinophils and clinical outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;131(2):152–160. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osawa H, Okauchi S, Taguchi S, Kagohashi K, Satoh H. Immuno-checkpoint inhibitor-associated hyper-eosinophilia and tumor shrinkage. Tuberk Toraks. 2018;66(1):80–83. doi: 10.5578/tt.66667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osawa H, Shiozawa T, Okauchi S, Miyazaki K, Kodama T, Kagohashi K, Nakamura R, Satoh H, Hizawa N. Time-totreatment failure and peripheral eosinophils in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021 doi: 10.20452/pamw.16049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]