Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies decay but persist 6 months postvaccination; lower levels of neutralizing titers persist against Delta than wild-type virus. Of 227 vaccinated healthcare workers tested, only 2 experienced outpatient symptomatic breakthrough infections, despite 59/227 exhibiting serologic evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, defined as presence of nucleocapsid protein antibodies.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus disease, SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, viruses, respiratory infections, zoonoses, vaccine-preventable diseases, BNT162b2, healthcare workers, United States

Neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) and binding antibodies (bAbs) appear to be associated with protection against symptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (1,2). Early assessments of the Pfizer-BioNTech (https://www.pfizer.com) BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine observed >95% effectiveness against predominantly Alpha infections (3), but the potential effect of waning postvaccine neutralizing titers is an ongoing concern (4).

Apparent increases in vaccine-breakthrough infections may result from waning antibody titers, increases in exposure risk, and reduced vaccine effectiveness against Delta and other variants. In mid-2021, Delta became the dominant virus type in the United States (5). Delta appears to cause increased hospitalization rates and has increased transmissibility compared with Alpha and other pre-Delta variants (6; Bolze et al., unpub. data, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.20.21259195). We report bAb and nAb levels as well as clinically overt and asymptomatic breakthrough infections that occurred among US healthcare workers in the Prospective Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion (PASS) study (7), conducted during January–August 2021.

The Study

The PASS study protocol was approved by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Federalwide Assurance no. 00001628, US Department of Defense Assurance no. P60001) in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human participants. Written consent was obtained from all study participants.

For the PASS study, we enrolled and followed generally healthy, adult healthcare workers (HCWs) at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, MD, USA) who were seronegative for IgG to SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (spike) and had no history of COVID-19, as previously described (7). We collected participants’ serum samples monthly and screened them for IgG against SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid protein (NP) in multiplex microsphere-based immunoassays, as previously described (Appendix) (E.D. Laing, unpub. data, ). In addition, we asked participants to obtain nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing at a designated COVID-19 testing center if they experienced symptoms consistent with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

To quantify spike IgG bAbs in World Health Organization binding antibody units (BAU), we interpolated IgG levels against an internal standard curve calibrated to the Human SARS-CoV-2 Serology Standard (Appendix Figure 1). We assessed serum samples for nAbs against SARS-CoV-2 wild type and Delta as previously described by using a well-characterized SARS-CoV-2 lentiviral-pseudovirus neutralization assay (Appendix) (8).

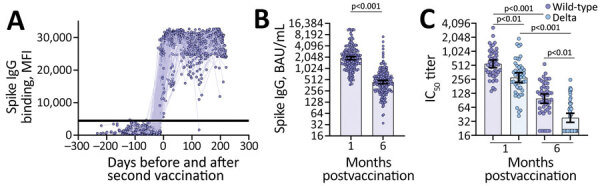

Figure 1.

Vaccine-induced binding and neutralizing antibody responses observed among US healthcare worker participants in the Prospective Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion (PASS) study, January–August 2021. A) MFI levels of vaccine-induced spike IgG binding before and after second vaccination in serum samples diluted 1:400 (n = 227 participants). Horizontal line indicates the positive or negative spike IgG threshold. B) Spike IgG binding antibodies (BAU/mL) quantified from serum samples collected 1 month (mean 36.9 days, range 23–81 days) and 6 months (mean 201.1 days, range 151–237 days) postvaccination (n = 187 participants). Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test performed; y-axis is log2-scale. C) Neutralizing antibody titers against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 wild-type and Delta variant from serum samples collected 1 month (mean 30.8 days, range 28–42 days) and 6 months (mean 200.1 days, range 189–219 days) postvaccination (n = 49 participants). Friedman ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons performed post-hoc; y-axis is log2-scale. All errors bars represent the geometric mean and 95% CIs. BAU, binding antibody units; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Excluding persons infected before January 31, 2021, the study followed 227 participants fully vaccinated with BNT162b2 vaccine and 17 unvaccinated participants. Participants were generally healthy, had a mean age of 41.7 (range 20–69) years, and were predominantly women (Table). Vaccinated and unvaccinated participants reported similar in-hospital time; >70% of each group worked in the hospital >15 days per month, and had similar rates of direct interaction with COVID-19 positive patients (monthly average of 47% for vaccinated and 45% for unvaccinated participants).

Table. Demographic characteristics of US healthcare worker participants in the Prospective Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion (PASS) study, January–August 2021*.

| Characteristic | BNT162b2 vaccinated | Vaccinated with 6-mo follow-up bAb | Vaccinated with 6-mo follow-up nAb titers | Unvaccinated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total |

227 (100) |

187 (100) |

49 (100) |

17 (100) |

| Sex | ||||

| F | 159 (70) | 131 (70) | 33 (67) | 13 (76) |

| M |

68 (30) |

56 (30) |

16 (33) |

4 (24) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 209 (92) | 175 (94) | 47 (96) | 16 (94) |

| Hispanic | 14 (6) | 10 (5) | 1 (2) | 1 (6) |

| Not reported |

4 (2) |

2 (1) |

1 (2) |

0 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 165 (73) | 139 (74) | 35 (71) | 9 (53) |

| Black | 26 (11.5) | 18 (9.5) | 4 (8) | 6 (35) |

| Asian | 23 (10) | 19 (10) | 8 (16) | 1 (6) |

| >2 races | 7 (3) | 6 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (6) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Not reported |

5 (2) |

4 (2) |

0 |

0 |

| Age, y, mean (range) | 41.7 (20–69) | 42.8 (21–69) | 44.7 (26–69) | 32.3 (19–50) |

*Values are no. (%) except as indicated. bAb, binding antibodies; nAb, neutralizing antibodies.

We observed seroconversion in all participants 1 month after the second vaccine dose (Figure 1, panel A). We quantified spike IgG bAbs at 1 and 6 months after full vaccination in the 187 vaccinated participants with serum samples collected at both timepoints. Spike IgG bAbs decreased from a geometric mean of 1,929 BAU/mL (95% CI 1,752–2,124 BAU/mL) at 1 month postvaccination to a geometric mean of 442 BAU/mL (95% CI 399–490 BAU/mL) at 6 months postvaccination (p<0.001) (Figure 1, panel B). Similarly, we observed decay of nAbs between the 1- and 6-month postvaccination timepoints. Peak SARS-CoV-2 wildtype nAbs decreased from a geometric mean titer (GMT) of 551 (95% CI 455–669 GMT) to 98 GMT (95% CI 78–124 GMT) 6 months after full vaccination (Figure 1, panel C). The GMTs of nAbs were significantly higher against wild-type compared with Delta SARS-CoV-2 at both timepoints after vaccination (Figure 1, panel C). In comparison, nAbs against Delta decayed from 279 GMT (95% CI 219–355 GMT) at peak to 38 GMT (95% CI 31–48 GMT) after 6 months. Quantitative IgG bAb (in BAU/mL) correlated with nAb titers (ρ = 0.70; p<0.001), demonstrating comparable decay of IgG bAbs and nAbs (Appendix Figure 2).

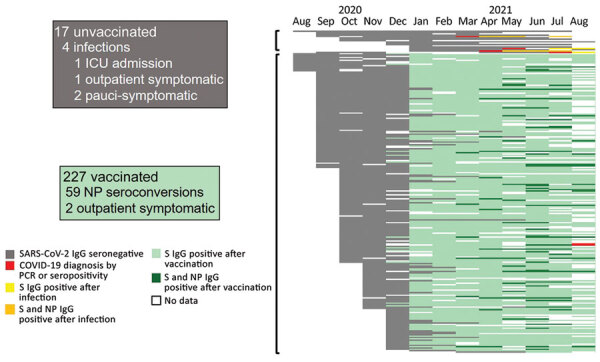

Figure 2.

Timeline of antibody responses and SARS-CoV-2 infections among US healthcare worker participants in the Prospective Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion (PASS) study, January–August 2021 (17 unvaccinated and 227 vaccinated participants). Each horizontal bar represents the infection, vaccination, and serologic status obtained monthly in all participants who had not been diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 by PCR or S protein IgG seroconversion by January 31, 2021. White spaces indicate no data. Gray bars represent negative S protein IgG. Red bars indicate month of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis by PCR positivity or S protein IgG seroconversion. Yellow bars indicate S protein IgG seroconversion after SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis in unvaccinated persons, and orange bars indicate presence of both S protein and NP antibodies in unvaccinated persons. Light green bars indicate S protein IgG seroconversion after vaccination. Dark green bars indicate detection of NP IgG in addition to S protein antibodies at timepoints postvaccination. S, spike protein; NP, nucleocapsid protein; ICU, intensive care unit; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

In addition to spike IgG bAbs, we also monitored for seroconversion of IgG bAbs to NP. Of vaccinated participants, 26.0% (59/227) had NP seroconversion during March–August 2021 (Figure 2). Only 2 had symptomatic, PCR-positive, vaccine-breakthrough infections, both of which were self-limited, outpatient cases. In the unvaccinated cohort, 4 participants had SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosed: 2 by PCR while experiencing symptomatic infection (1 outpatient case, 1 requiring intensive care) and 2 diagnosed by spike IgG seroconversion and who reported mild symptoms retrospectively. The frequency of NP seroconversions in the vaccinated population correlated with the frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infections diagnosed in the unvaccinated participants (23.5% [4/17]) (Figure 2), suggesting similar exposure rates.

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study of generally healthy, adult HCWs, we found that SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG bAbs and nAbs induced by BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination wane but remained detectable through 6 months after vaccination, corroborating results of another study (9). Consistent with another report (10), we observed significantly lower vaccine-induced nAb titers against Delta compared to wild-type virus. Asymptomatic infections determined by NP seroconversions were relatively frequent, but symptomatic infection was rare, and severe disease was absent.

We observed 1 of 17 unvaccinated persons have onset of severe COVID-19, versus no severe cases among 227 vaccinated participants. Of vaccinated persons, 2 had symptomatic, PCR-proven breakthrough infections, both of which were managed as outpatient cases. We observed that 26% of vaccinated participants developed antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 NP, suggesting that vaccinated persons experienced exposures to SARS-CoV-2 as frequently as the unvaccinated population, yet rarely had onset of overt clinical disease.

The strengths of the study include frequency of serologic assessments and use of variant specific nAb in addition to multiplexed antigen-specific IgG detection. Use of longitudinal serologic assessments (in addition to PCR testing when participants exhibited symptoms) enabled detection of asymptomatic and pauci-symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 exposures. Although our study was powered to show clear differences in antibody titers over time, limitations include the moderate size of the cohort and the small number of unvaccinated participants. Further, seasonal human coronavirus (HCoV) infections may drive cross-reactive IgG responses against SARS-CoV-2 NP. We mitigated the likelihood of HCoV-driven false-positives by using convalescent serum samples from persons with PCR-confirmed HCoV infections to establish the threshold for SARS-CoV-2 NP IgG positivity, which had a specificity of 94% in our multiplex assay (E.D. Laing et al., unpub. data). In a separate study, NP seroconversion reportedly occurred in only 71% of PCR-confirmed vaccine-breakthrough infections (11); thus, some instances of asymptomatic vaccine-breakthrough infections may have gone unnoticed.

We observed persistence of nAb titers against SARS-CoV-2 wild-type equal to or greater than the lowest dilution tested in 90% (44/49) of healthy adults 6 months after vaccination with BNT162b2. Neutralizing activity against Delta virus was lower,; only 47% (23/49) of participants maintained nAb titers above the lowest dilution at 6 months postvaccination. The decrease in nAb does not necessarily mean that persons have lost protection against severe COVID-19, however, given that nAb titers required for protection remain unknown and virus neutralization is only 1 function of antibodies. In addition, memory B cells and T cells have been detected 8–12 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, demonstrating that adaptive immune memory can be long-lasting (12,13). Further research is needed to understand the correlates of protection against moderate to severe COVID-19 for known and emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Even so, our results suggest that the BNT162b2 vaccine confers protection against severe clinical disease caused by the variants circulating in the United States through August 2021 for >6 months in generally healthy adults, even in the face of frequent exposures to the virus and waning antibody titers.

Additional information about durability of antibody response and frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infection 6 months after COVID-19 vaccination in healthcare workers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from the Defense Health Program and the CARES Act (grant nos. HU00012120067, HU00012120104, and HU00012120094) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (grant no. HU00011920111). The protocol was executed by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, a US Department of Defense program executed by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences through a cooperative agreement by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. This project has been funded in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (interagency agreement no. Y1-AI-5072).

E.D.L., C.D.W., W.W., R.V., T.C., K.M.H.-P., C.A.D., A.M.W.M., T.H.B., C.O., C.C.B., and E.M. are military service members or employees of the US government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C., §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the US government. Title 17, U.S.C., §101 defines a US government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the US government as part of that person’s official duties. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Naval Medical Research Center, the US Department of Navy, the US Department of Defense, the Henry. M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, the US Food and Drug Administration, or the US government. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the US government.

D.R.T., T.H.B., S.D.P., the Uniformed Services University Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Program (a US Department of Defense institution), and the Henry M. Jackson Foundation were funded under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement to conduct an unrelated Phase III COVID-19 monoclonal antibody immune-prophylaxis trial sponsored by AstraZeneca. The Henry M. Jackson Foundation, in support of the Uniformed Services University Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Program, was funded by the Department of Defense Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Defense to augment the conduct of an unrelated Phase III vaccine trial sponsored by AstraZeneca. Both these trials were part of the US government COVID-19 response. Neither is related to the work presented in this article.

Biography

Dr. Laing is an assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University, Bethesda. His primary areas of research are infectious and emerging zoonotic pathogens, with a focus on understanding mechanisms of virus virulence and co-evolutionary adaptations of bat immune responses to virus infections.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Laing ED, Weiss CD, Samuels EC, Coggins SA, Wang W, Wang R, et al. Durability of antibody response and frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infection 6 months after COVID-19 vaccination in healthcare workers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022 Apr [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2804.212037

References

- 1.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1205–11. 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert PB, Montefiori DC, McDermott AB, Fong Y, Benkeser D, Deng W, et al. Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science. 2021;375:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, Tyner H, Yoon SK, Meece J, et al. Prevention and attenuation of Covid-19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:320–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa2107058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowlkes A, Gaglani M, Groover K, Thiese MS, Tyner H, Ellingson K; HEROES-RECOVER Cohorts. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among frontline workers before and during B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant predominance—eight U.S. locations, December 2020–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1167–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker [cited 2021 September 15]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

- 6.Twohig KA, Nyberg T, Zaidi A, Thelwall S, Sinnathamby MA, Aliabadi S, et al. Hospital admission and emergency care attendance risk for SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) compared with alpha (B.1.1.7) variants of concern: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson-Thompson BM, Goguet E, Laing ED, Olsen CH, Pollett S, Hollis-Perry KM, et al. Prospective Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion (PASS) study: an observational cohort study of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination in healthcare workers. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:544. 10.1186/s12879-021-06233-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neerukonda SN, Vassell R, Herrup R, Liu S, Wang T, Takeda K, et al. Establishment of a well-characterized SARS-CoV-2 lentiviral pseudovirus neutralization assay using 293T cells with stable expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248348. 10.1371/journal.pone.0248348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas SJ, Moreira ED, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Six Month Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1761–73. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chia PY, Ong SWX, Chiew CJ, Ang LW, Chavatte J-M, Mak T-M, et al. Virological and serological kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant vaccine breakthrough infections: a multicentre cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;S1198-743X(21)00638-8; Epub ahead of print. 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollett SD, Richard SA, Fries AC, Simons MP, Mende K, Lalani T, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine breakthrough infection phenotype includes significant symptoms, live virus shedding, and viral genetic diversity. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab543; Epub ahead of print. 10.1093/cid/ciab543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:eabf4063. 10.1126/science.abf4063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner JS, Kim W, Kalaidina E, Goss CW, Rauseo AM, Schmitz AJ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces long-lived bone marrow plasma cells in humans. Nature. 2021;595:421–5. 10.1038/s41586-021-03647-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information about durability of antibody response and frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infection 6 months after COVID-19 vaccination in healthcare workers.