An abundance of past research has indicated that individuals with a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) engage in less frequent weekly exercise than individuals with a lower BMI (e.g. Spees, Scott, & Taylor, 2012). Although frequent exercise can aid weight loss efforts, it is also possible that the relationship between exercise and BMI is bi-directional, and that having a higher BMI leads individuals to engage in less physical activity. Given the known health benefits of exercise (e.g. King, Hopkins, Caudwell, Stubbs, & Blundell, 2009), it is important for people across the weight spectrum to exercise regularly, and therefore it is important to understand the complex relation between exercise and BMI. The focus of our research is to understand the direction of and mechanisms for the observed relation between BMI and exercise frequency.

One mechanism that has been suggested as an explanation for the negative relation between BMI and exercise is weight stigma. Individuals who have higher body weight frequently experience stigma and prejudice related to their weight (Puhl & Heurer, 2010), in the form of, for example, bullying and taunts, or outright discrimination in terms of jobs, education, or relationships. These experiences have been shown to be related to reduced exercise levels and increased motivation to avoid exercise (Vartanian & Shaprow, 2008), as well as a variety of other negative mental and physical health outcomes, including unhealthy eating patterns, depression and anxiety (Hunger & Major, 2015; Major, Eliezer, & Rieck, 2012; Puhl & Heuer, 2012; Durso & Latner, 2008), and even weight gain (Durso et al., 2012; Sutin &Terracciano, 2013).

Although the link between weight stigma experiences and reduced exercise among individuals with a higher body weight has been repeatedly documented (Pearl, Puhl & Dovido, 2015; Vartanian & Novak, 2011; Vartanian & Shaprow, 2008; Han, Agostini, Brewis, & Wutich, 2018), the distinct psychological processes that explain how stigma actually causes an individual to avoid exercise remain unclear. For example, in a of patients after bariatric surgery, higher levels of self-reported experience with stigmatizing weight-related situations and higher weight-bias internalization were shown to be indirectly related to reduced physical activity via exercise avoidance motivation (Han, Agostini, Brewis, & Wutich, 2018). However, it still remains unclear how these lifetime experiences are related to exercise avoidance motivation.

In another study, internalization of anti-fat attitudes and societal standards of attractiveness have been shown to be related to exercise avoidance (Vartanian & Novak, 2011), suggesting that the more someone accepts or believes these cultural attitudes related to weight and thinness, the more likely they are to avoid exercise. But weight bias internalization, although important, only partially mediates the relation between weight stigma experiences and exercise behavior. The direct path from weight stigma experiences to exercise behavior remains significant (Pearl, Puhl and Dovido, 2015), allowing for the possibility that other variables may more fully explain the relation.

Our research examines another potential mediator of the relation between BMI and exercise frequency, social physique anxiety. Social physique anxiety (SPA) is the extent to which individuals worry about being negatively evaluated or judged by others because of their body or physical appearance. Rather than measuring the frequency of stigma one has experienced or the intensity of one’s internalization of societal standards of thinness, SPA assesses the affect associated with perceived negative social evaluation of one’s body. SPA is not a measure of weight stigma per se, but past studies have found an association between perceived social unacceptability of one’s weight, weight stigma, and body image concerns for individuals with a higher body weight (Annis, Cash, Hrabosky, 2004; Farrow & Tarrant, 2009).

There is also evidence that SPA is associated with individual’s particular reasons for exercising. For example, for females, SPA is more highly associated with exercising to enhance one’s appearance (e.g., for weight control, body tone, or attractiveness) relative to other reasons such as exercising for health (Crawford & Eklund, 1994; Eklund & Crawford, 1994). Women with high SPA are also more likely to exercise privately than women with low SPA (Spink, 1992), which may help explain why individuals with high BMI exercise less often, at least in public places.

Given that SPA encompasses both internalization of the thin ideal and fear of being judged against this ideal, we believe it is likely an important mediator of the relation between BMI and exercise. Specifically, SPA may be more proximally related to exercise decisions and play a more direct role in behavioral outcomes than weight stigma or weight bias internalization. The current studies are the first to test the hypothesis that the association between BMI and exercise is mediated by social physique anxiety. We tested this hypothesis using two online surveys, first as an exploratory hypothesis, and then as a pre-registered hypothesis in a confirmatory study.

Study 1

We used an online survey to examine whether SPA mediates the relation between BMI and weekly exercise. We hypothesized that higher BMI would be associated with decreased exercise specifically because those with higher BMIs worry more about negative judgements of their body from others, thus decreasing their willingness to be seen exercising. We also examined the relation between BMI and beliefs in the importance of fitness and in the importance of health, to rule out the frequently proposed possibility that differences in levels of physical activity were related to differences in these beliefs.

Study 1 Methods

Participants and Procedure

All study procedures and materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Ninety-seven American adults (age: M = 37.67 years, SD = 11.74; gender: 51.5% male, 48.5% female; race/ethnicity: 78.4% White, 9.3% Mixed Race/Other, 7.2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5.2% Black/African American) were surveyed through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform for surveys and simple tasks that has been shown to elicit samples that are as diverse as other internet samples, and more diverse than college samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). Eight of the original 105 participants did not answer questions on BMI, SPA, or weekly exercise, and were excluded. Participants’ BMI (M= 25.97, SD = 4.71) was calculated using self-reported height and weight.

Measures

Weekly exercise

Participants were asked: “In a typical week, how many days do you do any physical activity or exercise of at least a moderate intensity (e.g. brisk walking, running, bicycling, swimming, weight-lifting, yoga)?” They chose the number of days per week ranging from 0 days to 7 days.

Social physique anxiety

We measured SPA using the original 11-item scale (Hart, Leary, & Rejeski, 1989). The items include “In the presence of others, I feel apprehensive about my physique or figure,” and “Unattractive features of my physique make me nervous in certain social settings.” Participants rated each item from (1) not at all characteristic of me to (5) very characteristic of me, and a higher score indicates higher levels of SPA. The reliability of the scale in this study was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94).

Fitness and health importance

Participants rated the following two face-valid statements on a scale from (1) strongly disagree to (6) strongly agree: “Maintaining a certain fitness level is important to me” and “Maintaining a healthy weight is important to me.”

Analysis

We tested whether SPA mediated the effect of BMI on exercise frequency. The psych package in R Statistical software was used to test for mediation, which uses least squares linear regression to calculate the total effect of BMI on exercise as well as the direct effects of BMI on SPA, SPA on exercise, and the indirect effect of BMI on exercise through SPA. The confidence interval for the indirect effect was calculated using bootstrap analysis with replacement (n iterations = 5000) because it does not require that the data are normally distributed and is particularly useful for small sample sizes. We conducted analyses controlling for sex, age, and race/ethnicity, but these variables were ultimately removed as they did were not significant predictors of the total nor direct effects (p > 0.05).

Study 1 Results

Descriptives

Means and standard deviations of all variables are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study 1 and Study 2 Descriptive Statistics

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||

| BMI | 25.85 | 4.69 |

| SPA | 2.54 | 1.08 |

| Exercise | 4.41 | 1.88 |

| Fitness & Health Importance | 4.79 | 0.96 |

| Study 2 | ||

| BMI | 25.89 | 6.67 |

| SPA | 2.93 | 0.99 |

| Exercise | 4.37 | 1.83 |

| Gym-goers | 3.60 | 1.04 |

| Body Concern | 2.83 | 1.42 |

| Gym Environment | 3.07 | 0.89 |

| Athletic Apparel | 2.16 | 1.24 |

| Tech. Knowledge | 2.66 | 1.14 |

| Tech. Judgment | 3.39 | 1.21 |

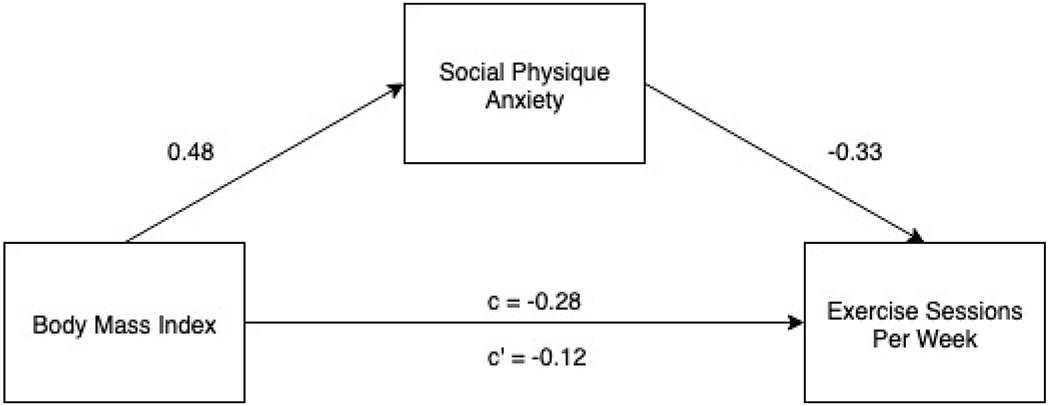

Test of the mediation model

Results of our mediation analysis to test the hypothesis that social physique anxiety mediates the effect of BMI on exercise frequency (See Figure 1) indicated that BMI was a significant predictor of SPA (b=.46, se=.09, p<.001), and that SPA was a significant predictor of exercise sessions per week (b=−.33 , se=.10, p<.001). BMI was no longer a significant predictor of exercise per week after controlling for SPA (b = −.12, se =.10, p=.26). These results support the mediational hypothesis. Approximately 17% of the variance was accounted for by the predictors (r2 = .167, F (2, 94) = 9.45, p < 0.001). The indirect effect was tested using a bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 samples. These results indicated the indirect coefficient was significant (b=−.16 , se=.06, 95% CI = [−.27 −.05]). Therefore, higher BMI is associated with increased SPA, which, in turn, is associated with decreased weekly exercise.

Figure 1.

Study 1 Mediation Model

Test of relation between BMI and exercise and fitness importance

In line with our prediction and in opposition to popular belief, bivariate correlations revealed that neither fitness importance (r = −.15, p = .13) nor exercise importance (r = −.07, p = .47) were significantly related to BMI. People with higher BMI levels do not view fitness and exercise as less important than people with lower BMI levels.

Study 1 Discussion

The results from Study 1 provided initial evidence that the relationship between BMI and exercise is mediated by SPA, and also fail to support the popular notion that individuals with high BMI lack a concern for their health and weight. Along with social physique anxiety, individuals’ perceptions of exercise culture may also play a role in the relation between BMI and exercise. For example, women in rehabilitation settings who reported stronger preferences for private rehabilitation areas also tended to report higher SPA (Driediger, McKay, & Hall, 2017). This conception of the exercise environment extends beyond the physical environment to people’s perceptions of others who exercise and to views about commonly worn exercise apparel. For example, women who report higher SPA also tend to report an increased preference for all-female environments and apparel that obscures one’s body (Driediger at al., 2017). Finally, nursing students with higher SPA were found to be more likely to exercise in private spaces compared to students with lower SPA (Spink, 1992). We suggest that individuals’ perceptions of exercise culture and environments may help explain not only the relation between BMI and exercise, but also may provide insight into the variety of thought processes that lead individuals with high SPA to engage in exercise less frequently.

Study 2

Study 2 uses a parallel convergent mixed methods design in which quantitative and qualitative data are simultaneously collected (Fetters, Curry, & Creswell, 2013. The primary aims of Study 2 were 1) to examine whether the mediation model from Study 1 was replicated in a new sample and 2) to examine a variety of contextual variables (e.g., one’s perception of gym culture or one’s feelings about exercise clothing) that might provide further insight into the relation between SPA and weekly exercise. We were interested in whether the relation between SPA and exercise differed based on these contextual variables, and we explored them using both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For example, is the association between SPA and exercise stronger among those who perceive the gym environment to be more hostile? Is this association weaker among those who perceive the gym environment to be more welcoming? Understanding these associations may shed light on more specific concerns individuals may have as they are choosing whether to exercise. We also asked participants to report their perception of the direction of the relation between worrying about their body and engaging in exercise.

Preregistration and Hypotheses

The Study 2 protocol and hypotheses were preregistered prior to collecting the data (osf.io/d86jw/). This preregistration is a timestamped, watermarked file documenting our hypotheses, and it was submitted prior to data collection. This study follows our preregistered protocol with one exception1. Our primary hypothesis was that we would replicate the mediational findings from Study 1. The remaining findings are exploratory in nature. We examined six categories of contextual variables (i.e. friends, peers, body, gyms, apparel, and technique) we believed would help us to better understand the relation between SPA and exercise behavior. First, we examined each of these variables as a moderator of the relation between SPA and exercise. Participants were also prompted to describe a personal experience related to their response for each contextual variable. We used these open-ended responses as a means of more richly understanding the nature of each contextual factor. Finally, participants reported whether they thought that body-related anxiety was a reason someone does not exercise, was the result of not exercising, both of these options, or neither of these options.

Study 2 Methods

Participants and Procedure

All study procedures and materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Two hundred and ninety-two American adults with a mean age of 33.98 years (SD = 10.5) participated in the study. Of the participants, 58.8% identified as male, 41.5% as female, and 0.7% of respondents selected that their gender was not listed. The sample was 64.6% White, 21.6% Asian/Pacific Islander, 7.6% Black/African American, and 6.2% Mixed Race/Other. The mean BMI was 26.05 (SD = 6.71). Of the original 307 participants, 15 were excluded because they did not answer questions on BMI, SPA, or weekly exercise. Like Study 1, the survey was conducted through Amazon Mechanical Turk. Turk Prime, an extension of Amazon Mechanical Turk, was used to ensure that the same participants did not participate in both studies.

Measures

SPA and exercise frequency

The measures of SPA (Study 2 Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92) and exercise frequency are the same as those described in Study 1.

Aspects of the exercise context

All aspects of the exercise context were measure by rating items on scales from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

Perception of other gym-goers.

Participants rated three items about how they perceive others in exercise settings, with higher numbers reflecting feeling more welcomed by other gym-goers. The items were related to how frequent gym-goers viewed people new to the gym, and how welcoming people were of all body types at the gym. For example, participants were presented with the following: “Most people who go to the gym feel that people of all body types and levels of fitness should be welcome at the gym.”

Body concern.

Participants rated three items about how they think about their body in exercise settings, with higher numbers reflecting more body concerns at the gym. The questions were related to the embarrassment participants may have felt about the shape of their body while exercising. For example, “The shape of my body makes me embarrassed to exercise.”

Perception of the gym environment.

Participants responded to five items related to how comfortable they have felt while working out in gyms, how inclusive an atmosphere that gyms try to create, and gym staff’s behavior towards people who are out of shape. Higher numbers indicate more concerns about the gym environment. For example, “Gyms cater to those who are already in shape.”

Comfort in athletic apparel.

Participants rated three items about their feelings when wearing exercise clothing and how comfortable the fit of exercise clothing is for them. For example, “I worry about how I look in exercise clothing.”

Technical knowledge.

Participants rated two items about their confidence in their exercise technique and their perceived knowledge of proper exercise technique. For instance, “I am familiar with proper exercise techniques used for most of the activities I do.”

Technical judgement.

Participants rated two items about their views of others who do not use proper exercise technique and how knowing technique better would change how often they worked out. For example, “People who do not exercise using proper form look out of place or awkward.”

Perception of the relationship between SPA and exercise

Participants selected whether they believed that worrying about their body shape led them to not exercise, whether not exercising led them to worry about their body shape, whether both statements applied to them, or whether neither of the statements applied to them. They were then asked to explain their choice of statement in an open-ended format.

Analysis

The same mediation analysis as Study 1 was used for Study 2. Mixed-methods analysis was used to examine the potential moderator variables. We first tested each variable quantitatively as a moderator. Specifically, we used linear regression to examine whether the interaction between each variable, entered as a continuous variable, and SPA was significantly related to exercise above and beyond the main effects. We then probed significant reactions to examine the simple slopes one standard deviation above and one standard deviation below the mean. Each of the open-ended responses of the significant moderators was then examined to better understand participants’ thought processes about each moderator and how it relates to their willingness to exercise. These open-ended responses are used to descriptively highlight the significant quantitative findings that we report. Finally, participant perceptions of the relation between SPA and exercise were examined descriptively. Open-ended responses were again used to better understand participant responses.

Study 2 Results

Descriptives

Means and standard deviations of all variables are in Table 1.

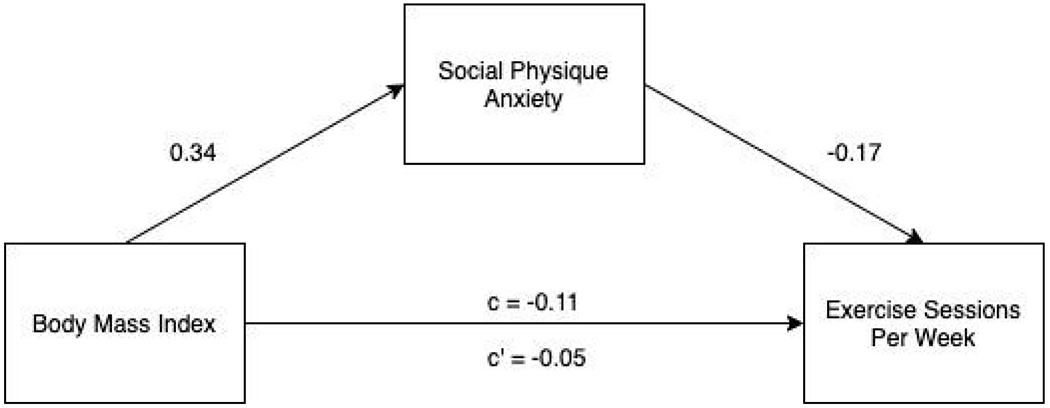

Replication of the mediation model

Like study 1, the psych package in R Statistical Software was used to test the hypothesis that social physique anxiety mediates the effect of BMI on exercise frequency (see Figure 2). Results supported our preregistered hypothesis that BMI was a significant predictor of SPA (b = .34, SE = .06, p < .001) and that SPA was a significant predictor of exercise sessions per week (b = −.17, SE = .06 p < .01). BMI was no longer a significant predictor of exercise per week after controlling for SPA (b = −.05, se =.06, p =.38), which is consistent with evidence of mediation, as we hypothesized. These results replicate Study 1. Approximately 4% of the variance was accounted for by the predictors (R2=.04). The indirect effect was tested using a bootstrap estimation approach with 1000 samples. These results indicated the indirect coefficient was significant (b = −.06, sd = 0.02, 95% CI = [−.11 −.01]). Therefore, higher BMI is associated with increased SPA, which, in turn, is related to decreased weekly exercise.

Figure 2.

Study 2 Mediation Model

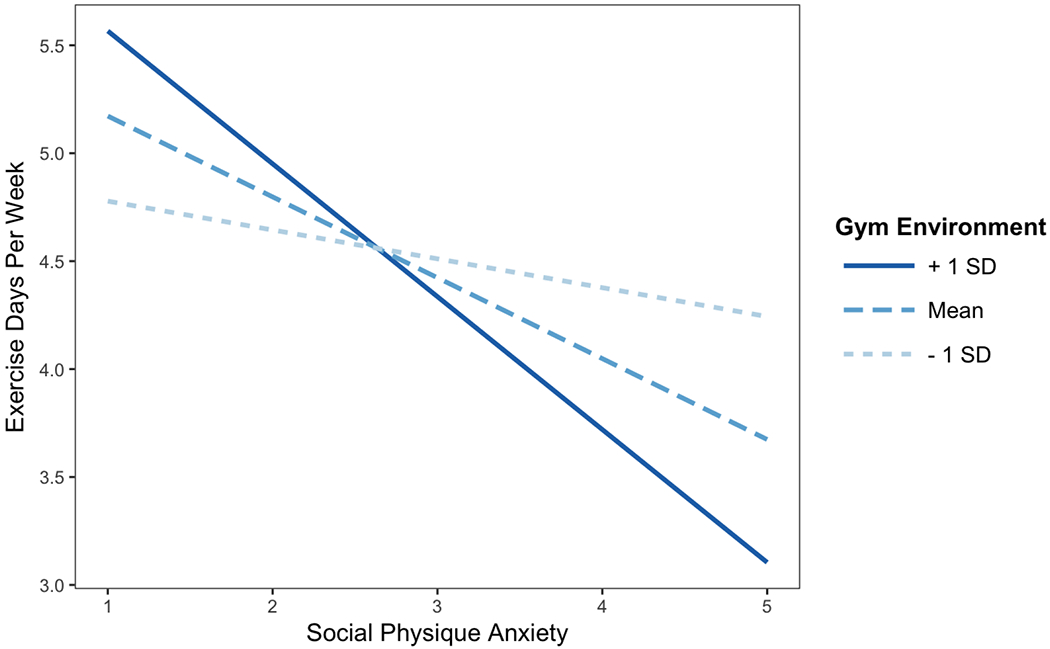

Test of moderation for each contextual variable

The 1m package in R was used to test for moderation. We separately entered each of the six contextual variables as potential moderators of the relation between SPA and exercise. The interaction for SPA and gym environment (b = −0.26, p <0.05) was significant (see Figure 3). The interactions for SPA and discomfort with body while exercising (b = −0.13, p = 0.05) and perception of gym-goers (b = 0.14, p = 0.09) were each marginally significant moderators of the relation between SPA and exercise. The interactions between SPA and gym-related technical knowledge (b = −0.00, p = 0.99), gym-related technical judgment (b = −0.04, p = 0.63), and comfort in athletic apparel (b = −0.02, p = 0.82) each fell short of statistical significance.

Figure 3.

The interaction between SPA and perceived gym environment on exercise per week

Using the jtools package in R, the significant and marginal interactions were probed by testing the conditional effects at three levels of each variable (one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean). For gym environment and discomfort with body, SPA was significantly related to weekly exercise at one standard deviation above the mean (gym: b = −0.62, p < .001; body: b = −0.51, p < 0.01) and at the mean (gym: b = −0.37, p < 0.001; body: b = −0.31, p < 0.05), but not at one standard deviation below the mean (gym: b = −0.13, p =0.32; body: b = −0.11, p =0.46). This suggests that increased social physique anxiety is related to reduced exercise frequency when concerns about the gym environment are high or average, but not when those concerns are low. The same relationship was found with discomfort with one’s body. For perception of other gym-goers, SPA was significantly related to weekly exercise at one standard deviation below the mean (b = −0.29, p < 0.05), but not at the mean (b = −0.14, p =0.24) or above the mean (b = 0.01, p = 0.92), indicating that social physique anxiety is related to reduced exercise frequency when individuals feel uncomfortable with other gym-goers, but not at average or high levels of comfort with other gym-goers.

Qualitative results for significant moderators

Perception of the gym environment.

Perceptions of the gym environment moderated the relationship between SPA and weekly exercise, and it is again evident from differences in qualitative responses between those with high and low SPA. For example, responses from individuals high in SPA included the following: “I used to avoid gyms because I was very overweight. I was ashamed and didn’t feel like I fit in at a gym,” and “I left a gym because of the rude behavior of the staff. They pretend that I am too fat, and I can’t be slim. They don’t pay attention to me. It hurts a lot to me.” In contrast, those low in SPA responded by writing, for example, “I have always felt comfortable in a gym and haven’t paid much attention to the others around,” and “I have never felt obese or too overweight to be a part of a gym. However, I have been a part of gyms where I could see a stark difference in gym goers and the general population, and an intimidation aspect was definitely present.”

Body concern.

Qualitative responses again differed between those high and low in SPA. For example, respondents high in SPA wrote, “I was once in shape, but then I didn’t care and got fat, now that I’m fat, I care but not brave enough to exercise” and “If I was more in shape, I would probably work out more. It would be easier to do so. But in order to get there, you must exercise more. It’s a vicious cycle.” Interestingly, although individuals with low SPA do not experience the same body judgement, they do recognize its existence and its implications. For example, an individual low in SPA wrote, “The reality is that most people at the gym are just there to work out. But the perception of judgement still feels very real for a lot of people who are new to fitness. Planet Fitness even addresses this fear in their slogan: ‘no judgments.’”

Perception of other gym-goers.

The test for moderation showed that views of gym-goers moderated the relation between SPA and exercise. Qualitative responses further revealed the ways in which individuals with high SPA described other gym-goers. For example, one individual wrote, “I don’t currently work out at a gym; when I did belong to a gym, it was intimidating to be around really fit people - though I doubt they even notice anybody else.” Another wrote, “I often feel extremely self-conscious at the gym because I feel like people look at me and think I look fat and gross. I have NEVER had anyone look at me funny or say anything nasty to me at the gym as a matter of fact everyone is always nice and encouraging but I still feel ashamed of my body and weight.”. Moreover, one participant wrote, “I went to a gym to jump start my weight loss program. The place was full of ‘gym rats’ and bodybuilders who looked like they spent every waking moment there! I felt very uncomfortable when I tried to use certain equipment. I almost felt that I was stealing it from some of the patrons and that I didn’t deserve to be using it. One time, a woman stood right next to the apparatus I was on until I got off--she was very impatient.” In contrast, qualitative responses of individuals low in SPA tended to reflect more positive experiences with other gym-goers. For example, their explanations included the following: “I don’t think they really pay attention to be honest”, “No I don’t [worry about other gym-goers] because I’m not fat or overly out of shape,” and “I don’t feel as though I’m being judged by others who work out. I think about it like this, if I’m going to the gym to work out, regardless if I’m overweight or obese, I should be looked at as a person who has enough willpower to get up and do something about my weight.”

Perception of the relationship between SPA and exercise

Participants’ intuitions about the relation between SPA and exercise did not correspond with the quantitative findings from these studies, indicating that these processes may be acting subconsciously. Only 7.5% of participants believe that, “Worry about [their] body shape or size leads [them] to not exercise.” Many more participants (45.3%) endorsed the reverse relation, that not exercising led them to worry about their body. However, we did not find mediation for this alternative model with exercise days per week as the mediator and social physique anxiety as the outcome in Study 1 nor Study 2. An additional 10.7% of participants reported that they believed that both worry about their body shape or size led them not to exercise and that not exercising led them to worry about their body shape or size, and 36.5% reported that neither statement was true of them. One participant who thought not exercising led to worry said, “I feel that not exercising would make me fat and out of shape,” while another participant who thought their exercise and anxiety were unrelated said, “I am fine with the way my body looks and I exercise because I want to stay healthy.”

Study 2 discussion

Study 2 replicated the mediation model from Study 1 with a larger sample size, supporting our hypothesis that SPA mediates the relationship between BMI and weekly exercise. In addition, Study 2 provided evidence that gym environment, perception of gym-goers, and discomfort with body while exercising may moderate the relation between SPA and exercise. Qualitative responses further revealed differences in the experiences of those high and low in SPA. Those high in SPA talk about wanting to be in shape in order to work out and avoiding the gym because of feelings of judgement from other gym-goers, and even feeling as though they are in the way of other more fit patrons. In contrast, although some individuals lower in SPA do realize that gyms can be places of judgement, they seem to rationalize this by saying that people should be looked at as a person with willpower simply because they made it to the gym. Although this is a nice sentiment, it is clear that it is not how those high in SPA experience the gym environment. Finally, and interestingly, most participants do not believe that worry about their body leads them to avoid exercise. Perhaps when people believe they are too tired, too sick, too overwhelmed, or too stressed to go to the gym, they may be partly experiencing worry about being judged for their body.

General Discussion

Our two studies suggest that SPA may mediate the relation between BMI and weekly exercise. Furthermore, Study 2 suggested specific contextual variables that may moderate the relation between SPA and weekly exercise, contributing to our understanding of the role of the gym environment itself in increasing or decreasing the relation between SPA and exercise. Our results contribute to the literature on the relation between BMI and exercise as they demonstrate SPA mediates the relationship between BMI and exercise more robustly than variables such as lifetime weight stigma experiences or weight bias internalization (Vartanian & Novak, 2011; Vartanian & Shaprow, 2008).

These results are the first to examine the psychological mechanisms that explain how weight stigma and weight bias internalization lead to decreased exercise behavior. Feeling like an outsider, feeling vulnerable, or feeling uncomfortable are all feelings that most people would prefer to avoid experiencing. Our research suggests that for someone who has a higher body weight, going to the gym can be a vulnerable, uncomfortable experience in which they worry that people will judge them as unworthy of being in the gym. Furthermore, these studies provide evidence that health and fitness importance may not vary by body weight, yet the more someone weighs, the less apt they are to actually exercise.

Limitations

A primary limitation to this study is that it is cross-sectional and uses somewhat modest online samples of 100-300 individuals. Given the complicated nature of weight, there are likely many reasons that people of a certain body shape or size are more or less likely to exercise. However, our goal is to highlight one important mechanism by which this effect occurs, and to what extent. We believe this research is a sound contribution to the literature on stigma, body shame, and health behavior in applied contexts. Another limitation is that weight and height were self-reported in this research instead of being measured, potentially reducing their validity. And BMI itself is only a height to weight ratio and therefore cannot account for actual muscle mass or adiposity. However, like most work in this area, we were limited to using BMI. The measures we used for the contextual variables, although face valid, are not validated measures.

Although our research suggests that SPA is one of the main mechanisms that explains the connection between BMI and exercise frequency, we are by no means suggesting that individuals are necessarily consciously aware that SPA is leading them to avoid exercise. Instead, we are suggesting that when people decide that they are too tired, too sick, too busy, or just get a feeling that they really do not want to go to the gym, they may actually be avoiding an anxiety-provoking experience. Findings from Study 2 suggest a possible solution, however. Individuals may be more likely to work out despite their high SPA as long as it is in an environment in which feelings of inclusivity of all body types is promoted, and feelings of body judgement and judgement from other gym-goers are limited.

Future Research, Conclusions, and Implications

Future researchers might examine the effect of SPA on exercise using an in-person study design in which exercise behavior and psychological stress can be measured in real time. A longitudinal study design could be employed that would allow researchers to examine individual differences in mediating and moderating psychological mechanisms over time.

Future research may also explore some of the avenues for intervention suggested by this work. There is currently an abundance of attention in the media and in the weight loss industry on the idea that exercise leads to weight loss, decreased instances of heart disease, and decreased risk of Type II Diabetes. Our research shows that lack of information about the importance of exercise may not be the mechanism that should be addressed. More attention should be focused on trying to mitigate the harmful effects of weight stigma and social physique anxiety. In particular, more effort is needed to ensure that people feel welcome and comfortable at the gym, since social physique anxiety is a hurdle to exercise. Perhaps employee training at gyms, especially gyms targeting clients with a higher body weight, should focus on making individuals of all body types feel welcome. Creating small side rooms with only a few pieces of equipment where people feel as though their body is less on display might be helpful in decreasing SPA. Gyms could also create classes specifically for beginners in which people feel more comfortable having no knowledge of exercise or being out of shape. Small changes in workout settings, such as the ones proposed here, may go a long way toward promoting exercise among individuals who stand to benefit from – and even want to – exercise, but who avoid it out of anxiety over being judged by others. We believe this is a sensible way to promote healthy exercise while we continue to engage in the long, slow process of eliminating weight stigma entirely.

Footnotes

A measure of anti-fat attitudes was included in both studies. Based on an erroneous analysis of Study 1 data, we preregistered the hypothesis that anti-fat attitudes would also be a mediator. Upon realizing our error in the Study 1 analysis, we no longer focused on this hypothesis.

Reference

- Annis NM, Cash TF, & Hrabosky JI (2004). Body image and psychosocial differences among stable average weight, currently overweight, and formerly overweight women: The role of stigmatizing experiences. Body Image, 1, 155–167. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2003.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, & Gosling SD (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. 10.1177/1745691610393980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, & Watson AC (2006). The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 35–53. 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford S, & Eklund RC (1994). Social physique anxiety, reasons for exercise, and attitudes toward exercise settings. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16, 70–82. 10.1123/jsep.16.1.70 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl NS, Johnson CE, Rogers RL, & Petrie T,A (1998). Social physique anxiety and eating disorders: What’s the connection. Addictive Behaviors, 23, 1–6. 10.1016/S0306-4603(97)00003-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driediger MV, McKay CD, & Hall CR (2017). An examination of women’s self-presentation, social physique anxiety, and setting preferences during injury rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Research and Practice. 2017, 1–8. 10.1155/2017/6126509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, & Latner JD (2008). Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity, 16, S80–S86. 10.1038/oby.2008.448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, Latner JD, White MA, Masheb RM, Blomquist KK, Morgan PT, & Grilo CM (2012). Internalized weight bias in obese patients with binge eating disorder: Associations with eating disturbances and psychological functioning. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 423–427. 10.1002/eat.20933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund RC, & Crawford S (1994). Active women, social physique anxiety, and exercise. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 16, 431–448. 10.1123/jsep.16.4.431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow CV, & Tarrant M (2009) Weight-based discrimination, body dissatisfaction and emotional eating: The role of perceived social consensus. Psychology & Health, 24, 1021–1034. 10.1080/08870440802311348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetters MD, Curry LA, & Creswell JW (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48, 2134–2156. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Agostini G, Brewis AA, & Wutich A (2018). Avoiding exercise mediates the effects of internalized and experienced weight stigma on physical activity in the years following bariatric surgery. BMC Obesity, 5, 18. 10.1186/s40608-018-0195-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart EA, Leary MR, & Rejeski WJ (1989). The measurement of social physique anxiety. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11, 94–104. 10.1123/jsep.11.1.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunger JM, & Major B (2015). Weight stigma mediates the association between BMI and self-reported health. Health Psychology, 34, 172–175. 10.1037/hea0000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NA, Hopkins M, Caudwell P, Stubbs RJ, & Blundell JE (2009). Beneficial effects of exercise: Shifting the focus from body weight to other markers of health. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43, 924–927. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.065557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruisselbrink D, Dodge AM, Swanburg SL, & MacLeod AL (2004). Influence of same-sex and mixed-sex exercise settings on the social physique anxiety and exercise intentions of males and females. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26, 616–622. 10.1123/jsep.26.4.616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Eliezer D, & Rieck H (2012). The psychological weight of weight stigma. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 651–658. 10.1177/1948550611434400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl RL, Puhl RM, & Dovidio JF (2015). Differential effects of weight bias experiences and internalization on exercise among women with overweight and obesity. Journal of Health Psychology, 20, 1626–1632. 10.1177/1359105313520338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, & Heuer CA (2010). Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1019–1028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, & Heuer CA (2012). The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity, 17, 941–964. 10.1038/oby.2008.636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spees CK, Scott JM, & Taylor CA (2012). Differences in the amounts and types of physical activity by obesity status in US adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 36, 56–65. 10.5993/AJHB.36.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spink KS (1992). Relation of anxiety about social physique to location of participants in physical activity. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 74, 1075–1078. 10.2466/pms.1992.74.3c.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, & Terracciano A (2013). Perceived weight discrimination and obesity. PLoS ONE, 8, e70048. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR, & Novak SA (2011). Internalized societal attitudes moderate the impact of weight stigma on avoidance of exercise. Obesity, 19, 757–762. 10.1038/oby.2010.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR, & Shaprow JG (2008). Effects of weight stigma on exercise motivation and behavior: A preliminary investigation among college-aged females. Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 131–138. 10.1177/1359105307084318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z (2001). Setting for exercise and concerns about body appearance for women who exercise. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 93, 851–855. 10.2466/pms.2001.93.3.851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]