Abstract

Emivirine (EMV), formerly known as MKC-442, is 6-benzyl-1-(ethoxymethyl)-5-isopropyl-uracil, a novel nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor that displays potent and selective anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) activity in vivo. EMV showed little or no toxicity towards human mitochondria or human bone marrow progenitor cells. Pharmacokinetics were linear for both rats and monkeys, and oral absorption was 68% in rats. Whole-body autoradiography showed widespread distribution in tissue 30 min after rats were given an oral dose of [14C]EMV at 10 mg/kg of body weight. In rats given an oral dose of 250 mg/kg, there were equal levels of EMV in the plasma and the brain. In vitro experiments using liver microsomes demonstrated that the metabolism of EMV by human microsomes is approximately a third of that encountered with rat and monkey microsomes. In 1-month, 3-month, and chronic toxicology experiments (6 months with rats and 1 year with cynomolgus monkeys), toxicity was limited to readily reversible effects on the kidney consisting of vacuolation of kidney tubular epithelial cells and mild increases in blood urea nitrogen. Liver weights increased at the higher doses in rats and monkeys and were attributed to the induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes. EMV tested negative for genotoxic activity, and except for decreased feed consumption at the high dose (160 mg/kg/day), with resultant decreases in maternal and fetal body weights, EMV produced no adverse effects in a complete range of reproductive toxicology experiments performed on rats and rabbits. These results support the clinical development of EMV as a treatment for HIV-1 infection in adult and pediatric patient populations.

The discoveries in 1990 (25) that nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) could inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication in vitro and that their activities were potent and selective for the RT of HIV-1 (2, 11, 14) signaled an important advance for the treatment of HIV infection. In contrast to the nucleoside inhibitors of HIV-1 RT (NRTIs), the NNRTIs inhibited HIV-1 RT in a noncompetitive fashion and at a site on the RT distinct from the site inhibited by NRTIs (12). Clinical experience with NRTIs demonstrated that these compounds were able to reduce the morbidity associated with progression of HIV-1 infection. Nonetheless, due to acute and chronic toxicities, various degrees of antiviral activity, and, most significantly, the development of resistance when used in monotherapy, the NRTIs were limited in their ability to provide durable suppression of HIV-1 replication (22). The identification of NNRTIs, and likewise protease inhibitors, as potent inhibitors of HIV-1 replication that acted in a manner distinct from that of the NRTIs provided the basis for combination or “coactive” therapy (11). By inhibiting HIV-1 through distinct mechanisms, various combinations of NRTIs, protease inhibitors, and NNRTIs have yielded potent coactive regimens that have demonstrated durable suppression of HIV-1 replication (5, 34) and greatly improved clinical benefit.

The NNRTIs of the HIV-1-encoded RT are a chemically diverse set of structures that show extremely potent and selective antiviral activities (2, 3, 5, 12, 14). Despite the structural diversity seen in this group of inhibitors, X-ray crystallography studies of HIV-1 RT complexed with a number of different NNRTIs have shown all of these compounds to bind to a single allosteric site, approximately 10 Å from the polymerase catalytic site (13, 21). This binding site, which is predominantly hydrophobic, is located in the p66 palm domain of the p66/p51 heterodimer between the β-sheet comprising β4, β7, and β8 and the sheet comprising β9, β10, and β11 (21).

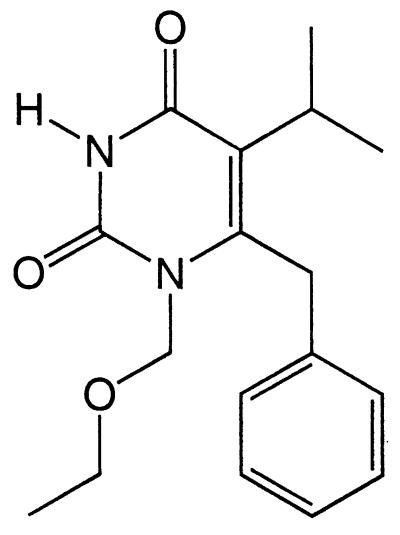

Emivirine (EMV) [6-benzyl-1-(ethoxymethyl)-5-isopropyl-uracil] belongs to the hydroxyethyl phenyl thymine (HEPT) series of NNRTIs (Fig. 1). This HEPT derivative is in a different class of compounds from nevirapine (26, 29), delaviridine (12), and efavirenz (17), the three NNRTIs currently approved for HIV-1 treatment. EMV is structurally similar to nucleoside analogs, but it has been shown to be a potent, noncompetitive inhibitor of HIV-1 RT (3, 16), with Ki values of 0.20 and 0.01 μM for dTTP- and dGTP-dependent DNA or RNA polymerase activity, respectively (37). Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50) and IC90 against laboratory-adapted strains of HIV-1 ranged from 1.6 to 19 nM and from 7.9 to 98 nM, respectively (3, 7). Against clinical isolates, the IC50 for EMV ranged from 2 to 40 nM (3, 7, 32). EMV was also effective against HIV-1 when it was combined with other therapeutic agents in vitro (16, 27, 31). EMV has been shown to bind strongly to human plasma proteins, with the extent of binding ranging from 78 to 96% at concentrations in human serum from 10 to 100% (4). The addition of 30% human serum to the extracellular medium resulted in a twofold increase in IC50, while the addition of 50% human serum resulted in a fivefold increase. However, protein binding is typically a saturable process and EMV has demonstrated activity in clinical trials (C. P. Moxham, K. Borroto-Esoda, D. Noel, P. A. Furman, G. M. Szczech, and D. W. Barry, Abstr. 10th Int. Conf. Antivir. Res., abstr. A44, 1997). EMV is also specific for HIV-1 RT and was without effect on HIV-2 (3, 5, 32). In this paper, we present the results of a preclinical safety and pharmacokinetic assessment of EMV. The results are in support of the rapid development of EMV as a potential agent for the treatment of HIV infection.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of EMV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytotoxicity.

Human bone marrow cells collected from normal healthy volunteers were used to assess bone marrow stem cell cytotoxicity. The mononuclear cells were isolated from whole heparinized marrow by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation as described previously (33). Cells were washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution and counted with a hemocytometer, and viability was assessed by Trypan blue dye exclusion. The cells were then plated in a bilayer of soft agar or methylcellulose (105/plate), and treated with a 0, 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 μM concentration of either EMV or zidovudine (AZT). After 14 days of incubation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, colonies (≥50 cells) were counted with an inverted microscope.

Mitochondrial toxicity.

Toxicity towards mitochondria was evaluated with HepG2 cells by measuring cell growth, the production of lactic acid in extracellular medium, mitochondrial DNA content, and structural changes in the mitochondria as previously described (10). HepG2 cells (2.5 × 104 cells/ml), grown in minimal medium with nonessential amino acids and supplemented with 10% serum, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, were plated in 12-well culture dishes and treated with various concentrations (0, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM) of EMV. After 4 days of incubation, cell growth was assessed by counting the number of cells. The medium was collected, and lactic acid was measured with an assay kit purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Corp. (Mannheim, Germany).

To determine the effect of EMV on mitochondrial DNA synthesis, HepG2 cells (5 × 104 cells) were treated with the above-named concentrations of EMV and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 14 days. The cells were then collected and heated at 100°C for 10 min in 0.4 M NaOH–10 mM EDTA. The extracted DNA was immobilized on a Zeta-Probe membrane with a slot blot apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). To detect mitochondrial DNA, an [α-32P]dATP-labeled specific human oligonucleotide mitochondrial probe, spanning nucleotides 4212 to 4242, was used at 2.5 × 106 dpm/ml (10). After autoradiography, the mitochondrial probe was removed by washing the membrane twice in 0.1 × SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and then in 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min. The total cellular DNA loaded on the membrane was standardized with a 625-bp fragment of a human β-actin cDNA plasmid probe labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (5 × 106 dpm/ml). Autoradiograms were scanned with a model CS9000U dual-wavelength flying-spot densitometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). The amount of mitochondrial DNA in each sample was expressed as a ratio of the mitochondrial oligonucleotide probe radioactive signal and the β-actin probe radioactive signal that was independent of DNA load.

The morphology of the HepG2 mitochondria was assessed by electron microscopy, as described previously (10). Briefly, HepG2 cells (2.5 × 104 cells/ml) were grown on 35-mm-diameter culture dishes in the presence of 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM EMV. Following a 4-day incubation period, the medium (with and without compound) was changed every other day. At day 8, the medium was removed and cells were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde for 1 h, rinsed in sodium phosphate buffer, and fast-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h. The cells were then gradually dehydrated with graded concentrations of ethanol (from 50 through 100%) to propylene oxide. The cells were then slowly infiltrated and embedded in epon. Thin sections were prepared with a Reichter-Jung ultramicrotome, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a Hitachi model 7000 electron microscope.

EMV measurement.

A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method for the quantification of EMV in plasma was developed and validated. The HPLC system consisted of a Waters Millennium System, Waters 717 WISP with refrigerated autosampler, Varian 9010 ternary pump, HPLC column heater, and Applied Biosystems model 783A programmable absorbance detector. EMV was extracted from plasma with diethyl ether after addition of 0.1 M boric acid and sodium hydroxide buffer, pH 10. The organic layer was transferred to a glass tube and evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen at room temperature. The residue was reconstituted in 250 μl methanol-acetonitrile-H2O (7:45:48, vol/vol/vol) and transferred to HPLC vials. A structural analog of EMV was used as an internal standard, and it was added to the plasma samples before extraction to correct for any variations in recovery. EMV was separated from the internal standard with a TSK-GEL ODS-80TM, 150- by 4.6-mm column (Tosohaas, Montgomeryville, Pa.) with an in-line frit filter under gradient conditions. The retention times for EMV and the internal standard were 8 to 10 and 12 to 15 min, respectively. The peaks were detected by UV absorbance at a 268-nm wavelength and integrated to quantify the EMV levels against the known internal standard. With an injection volume of 100 μl and a sample volume of 1.0 ml, EMV concentrations in plasma samples from mouse, rat, rabbit, and monkey ranged from 5 to 800 ng/ml. The standard curve was linear in the range of 2.5 to 1,000 ng/ml.

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion.

To guide the selection of an appropriate nonrodent animal model for EMV toxicology experiments, male Sprague-Dawley rats, beagle dogs, and cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) monkeys were given oral doses of the compound. EMV was suspended in 0.5% tragacanth gum, and a single dose of 50 mg/kg of body weight was given by gavage to seven groups of five male rats (body weight, 128 to 200 g) and to a group of four fasted male cynomolgus monkeys weighing 3.1 to 3.9 kg. Blood samples were collected from the rats at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h postdose and from the monkeys at 0.5, 1, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h postdose. For the dogs, EMV was placed in gelatin capsules and a single dose was given to four fasted males. Blood samples were collected at 5 min and 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h postdose. The blood samples were spun to separate the plasma, which was then analyzed for concentrations of EMV by the HPLC method described above. In this experiment, additional groups of male rats were given a single dose of EMV by injection into the caudal vein (0.88 mg/kg), by gavage (5 mg/kg), by intrarectal infusion (5 mg/kg) while the rats were anesthetized with urethane, and by infusion into the portal vein (0.25 mg/kg), again while the rats were anesthetized. The vehicles were 0.5% tragacanth gum in the cases of the oral and intrarectal doses and plasma (filtrate collected from untreated animals) in the cases of the intravenous and intraportal vein doses. Blood samples were collected at 5 min and 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after the intravenous dose; at 5 min and 0.25, 0.5, and 1 h after the intraportal vein dose; and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after the oral or intrarectal dose. Concentrations of EMV in plasma harvested from the blood samples were measured as described above to study absorption and first-pass metabolism in rats.

Absorption, tissue distribution, and excretion of EMV in male Sprague-Dawley rats were studied with [14C]EMV prepared by Mitsubishi Chemical Corp. EMV was labeled with 14C at the benzylic position attached to C-6. The specific activity was 2,029 MBq/mmol, and the radiochemical purity was 99.5%. A group of three rats, weighing 250 to 330 g, were given a single oral dose of [14C]EMV suspended in 0.5% tragacanth gum at a dose of 4,430 kBq 10 mg−1 kg−1. Blood samples were collected at 19 intervals from 5 min to 120 h postdose and analyzed for radioactivity. Seven male rats given [14C]EMV as described above were scanned for whole-body autoradiograms. One rat was used for an autoradiogram at 0.5, 1, 4, 8, 24, 96, and 240 h postdose. We studied excretion of EMV into urine and feces in five male rats given an oral dose of [14C]EMV of 364 kBq 10 mg−1 kg−1. They were placed in individual metabolism cages after the dose was administered. Urine was collected at 0 to 8 and 8 to 24 h postdose and every 24 h thereafter until 10 days postdose. Feces were collected every 24 h for 10 days postdose, lyophilized, weighed, and pulverized. 14CO2 in expired air was collected in a 20% solution of monoethanolamine for 24 h postdose. The radioactivity in urine was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (Tri-Carb 4530; Packard). Carbo-Sorb (Packard) was used to absorb the expired air collected, and the samples were counted after a liquid scintillator (Permafluor; Packard) was added. The blood and feces samples were weighed and placed into a Combusto-cone (Packard) and combusted in a Packard 360 sample oxidizer. Radioactivity was then determined by scintillation spectrometry.

We studied the biliary excretion of EMV in eight male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 229 to 244 g and having a surgically implanted bile duct cannula. [14C]EMV (814 MBq/mmol), prepared by Mitsubishi Chemical Corp., was suspended in 0.5% tragacanth gum, and a single dose was administered by gavage at 10 mg/kg of body weight (6.4 MBq or 173 μCi/kg). Bile samples were collected at 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h postdose. Urine samples were collected at 8, 24, and 48 h postdose, and feces samples were collected at 24 and 48 h postdose. Radioactivity in these samples and in water used to wash the individual cages was measured by scintillation spectrometry as described above. The cumulative excretion of radioactivity was expressed as a percentage of the dose administered.

For the distribution of EMV into brain, the compound was suspended in 0.5% tragacanth gum and given orally to male Sprague-Dawley rats (four per time point) at a dose of 250 mg/kg of body weight. The rats were anesthetized, and blood and brain samples were collected at 5 and 10 min and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h postdose. Plasma and brain, the latter homogenized in a fourfold volume of 1.15% KCl, were extracted and analyzed for concentrations of EMV by HPLC.

In vivo metabolism.

To study the effects of EMV on hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes, groups of five male Sprague-Dawley rats were given 0 (tragacanth vehicle), 15, 50, or 150 mg of EMV kg−1 day−1 by gavage for 14 days. The daily dose was divided and given in two equal installments separated by approximately 6 h, similar to the procedure in the rat toxicology experiments described below. Another group of four rats was given phenobarbital once a day at 80 mg kg−1 day−1 for 14 days as a positive control. Following necropsy, livers from the rats were perfused with 10 ml of saline via the portal vein, removed, and weighed. An aliquot (2.5 g) from the left lateral lobe was homogenized in 0.25 M sucrose on ice, and microsomes were isolated (20). Protein content, cytochrome b5 and P450 levels, and the activities of NADPH-cytochrome c reductase, aniline hydroxylase, aminopyrine N-demethylase, UDP-glucuronyltransferase, and 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylase were measured by standard spectrophotometric assays. Statistical differences were calculated by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's critical difference test (8) or, in the case of phenobarbital, Student's t test.

In vitro metabolism.

Three experiments designed to determine species-related differences in the microsomal oxidative metabolism of EMV and to identify the principal (human) cytochrome P450 enzymes involved were performed in vitro. First, liver microsomes from four humans, four cynomolgus monkeys, and four Wistar rats, all males, were isolated (20) and incubated for 25 min at 37°C with seven concentrations of EMV, ranging from 3 to 300 μM. Reactions were stopped by adding acetonitrile to the mixture. The samples were then extracted and analyzed by HPLC for EMV and its dealkylated product. Km values and maximum rates of metabolism (Vmax) were determined by the Gauss Newton method from Lineweaver-Burk plots. Second, pooled liver microsomes (0.2 mg of protein) isolated from male rats, male cynomolgus monkeys, and male humans were incubated for 0 to 60 min at 37°C with 100 μM EMV. The incubation times were selected to be higher and lower than the 25 min used in the first experiment. Reactions were stopped with cold perchloric acid (30%), and protein was precipitated by centrifugation. The supernatants were then analyzed by the HPLC-mass spectrometry (MS) method described below. Third, liver microsomes from 10 to 14 individual human donors were incubated for 0 or 15 min at 37°C with EMV at concentrations of 10 and 100 μM. Samples were prepared and analyzed by HPLC-MS. Some of the human samples were incubated with troleandomycin (20 or 100 μM) or nifedipine (20 μM), inhibitors of many cytochrome P450 3A-catalyzed reactions, or 5 μM furafylline, a cytochrome P450 1A2 inhibitor, to obtain chemical inhibition data for correlation analyses. The experiments were controlled by using microsomes with certified activity, by running samples in duplicate or triplicate, by using zero protein blanks, by comparing interindividual variation in the rates of EMV metabolism among samples of liver microsomes from 14 humans, and by using a Pearson product-moment correlation (8) to calculate regression coefficients between the metabolic data for EMV and several standard probe drugs.

EMV and its major oxidative metabolites were separated with a Zorbax XDB-C8 column (5.0 cm by 2.1 mm, 5-μm particle size; Chromatographic Specialties, Brockville, Canada) on a Hewlett-Packard model 1090 HPLC (Palo Alto, Calif.). The solvent system was a binary mobile phase consisting of 0.2% aqueous acetic acid (phase A) and 80/20 (vol/vol) methanol–0.2% aqueous acetic acid (phase B) and run with the following gradient: 50 to 100% phase B from 0.0 to 6.0 min, followed by 50% phase B from 6.1 to 7.5 min. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and the sample injection volume was 25 μl. The peaks were eluted onto an API 300 triple-quadrupole MS (Perkin-Elmer/Sciex, Concord, Canada) equipped with an APCI source operating in the positive ion mode. The heated nebulizer was set at 350°C with a pressure of 80 lb/in2 and an auxiliary flow of 1 liter/min. Perkin-Elmer/Sciex software was used for data analysis and integration. Selected ion monitoring (dwell time, 100 ms) of eight characteristic ions (m/z 243, 245, 257, 261, 273, 289, 303, and 319) was used to determine relative percentages of EMV and putative metabolites formed.

Safety pharmacology experiments.

Experiments performed to detect potential pharmacologic effects of EMV are listed in Table 1. EMV was suspended in 0.5% tragacanth gum and administered orally to mice and rats (3 to 10/group) at the concentrations indicated in Table 1. Male and female beagle dogs (five/group), anesthetized with pentobarbital, were given EMV intraduodenally to study a range of cardiovascular parameters. Isolated strips of ileum collected from male Hartley guinea pigs (five/group) were exposed in vitro to concentrations of EMV as large as 106 μM in an effort to detect potential pharmacologic effects on smooth muscle. Other parameters studied are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Safety pharmacology experiments performed with single doses of EMV

| Expt | Species | Route | EMV doses |

|---|---|---|---|

| General signs, activity | Mice | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| General signs, activity | Rats | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Spontaneous movement | Mice | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Hexobarbital sleeping time | Mice | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Electroconvulsive threshold | Mice | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Pentetrazole convulsive threshold | Mice | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Analgesic activity | Rats | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Effect on rectal temperature | Rats | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| In vitro effects on smooth muscle from ileum | Guinea pigs | 10−5, 10−6, 10−7 M | |

| Cardiovascular function in anesthetized beagle dogs | Dogs | Intraduodenal | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Gastrointestinal transit time | Mice | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

| Kidney function | Rats | Oral | 0, 30, 100, 300 mg/kg |

Toxicology experiments.

The acute toxicities of EMV and one of its putative metabolites, 6-benzyl-5-isopropyl-uracil (BIU), were assessed in CD male and female rats. Briefly, EMV and BIU were synthesized, suspended in 0.5% tragacanth gum, and administered to groups of five male and five female rats as single doses of 0, 2,083, 2,500, and 3,000 mg/kg. Animals were observed for 14 days, and body weights were recorded. In addition, preclinical safety evaluation experiments were performed with mice, rats, and cynomolgus monkeys as listed in Table 2. In all the experiments, EMV was delivered orally. The vehicle in the 1-month experiments was 0.5% tragacanth gum, and that in the subchronic and chronic experiments was 0.5% methylcellulose. The daily doses shown in Table 2 were given in two equal portions with 6 to 12 h between doses. The animals were bled at five to seven timed intervals to provide toxicokinetic data. In each subchronic experiment, the bleeding was performed on dose day 1 or 2 and repeated at the end of the dose period. In the chronic (6-month) rat study, bleeding was at dose day 1 and weeks 13 and 26. Monkeys in the 1-year experiment were bled at dose day 1 and weeks 4, 13, 26, and 52. Plasma was separated from the blood, extracted, and analyzed by HPLC for concentrations of EMV.

TABLE 2.

Toxicology experiments performed with EMV given by gavage

| Expt | EMV dose tested (mg/kg/day) | Dose(s) and/or effect

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Livera | Kidneyb | ||

| 3-month mouse | 0, 10, 40, 160 | 160 | 160 |

| 1-month rat | 0, 15, 50, 150, 500 | 150, 500 | 150, 500 |

| 6-month rat (3-month interim) | 0, 10, 40, 160 | 40, 160 | 160 |

| 1-month monkey | 0, 40, 200, 1000 | 200, 1000 | 200, 1000 |

| 3-month monkey | 0, 20, 60, 180 | 60, 180 | 180 |

| 1-year monkey | 0, 20, 60, 180 | 60, 180 | None |

| Rat fertility | 0, 10, 40, 160 | No effects at any dose | |

| Rat developmental toxicology | 0, 10, 40, 160 | Dam wt decreased at 160-mg/kg dose | |

| Rabbit developmental toxicology | 0, 10, 40, 160 | Dam wt decreased at 160-mg/kg dose | |

| Rat pre- and postnatal | 0, 10, 40, 160 | Dam and pup wt decreased at 160-mg/kg dose | |

Functional change in liver was attributed to enzyme induction.

Mild kidney effects were characterized by inconsistent increases in BUN, vacuolation, and degeneration of kidney tubular epithelial cells observed by light microscopy.

A 14-day preliminary experiment performed with groups of two (one male and one female) cynomolgus monkeys at EMV doses of 0, 30, 300, and 3,000 mg kg−1 day−1 was used to identify doses appropriate for further testing. One-month, subchronic, and chronic experiments of conventional design for CD (Sprague-Dawley strain) rats and cynomolgus monkeys, which included the use of reversibility groups, toxicokinetics, and histopathology, were performed according to the International Conference on Harmonization and Good Laboratory Practice guidelines. The chronic experiment with rats included an interim necropsy and histopathology at dose week 13 in addition to the necropsy and histopathology at 6 months. Dosing in the chronic monkey experiment continued for 1 year. A 3-month toxicology experiment was also performed with CD-1 mice to provide data to assist with the dose selection for the planned lifetime mouse carcinogenesis bioassay.

Reproductive toxicity tests with EMV included a rat fertility experiment, dose-range-finding experiments with pregnant rats and rabbits, developmental toxicology (teratology) experiments with rats and rabbits, and a pre- and postnatal experiment with rats. These experiments were also performed according to Good Laboratory Practice and International Conference on Harmonization guidelines. The vehicle in all of these studies was 0.5% methylcellulose. The daily doses tested (Table 2) were given in two equal installments with approximately 6 h between doses.

Three genetic toxicology experiments were performed with EMV. A reverse-mutation assay with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (1) used TA94, TA98, TA100, and TA2637 strains to test EMV at concentrations up to 5 mg/plate, with and without metabolic activation. A stock solution of 50 mg of EMV per ml, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, was used for the assay; the solvent was also used as a negative control. An in vitro assay for chromosomal aberrations (23) was performed with Chinese hamster ovary cells incubated with EMV at concentrations up to 150 μg/ml for 17.8 h without metabolic activation. Incubation conditions for a 3-h exposure included EMV at concentrations up to 200 μg/ml without metabolic activation (150 μg/ml with metabolic activation). Finally, an in vivo micronucleus assay (19) was performed with groups of five male CD rats given an oral dose of EMV of 0, 500, 1,000, or 2,000 mg kg−1 day−1, administered as two equal doses separated by 6 h. Numbers of micronuclei were counted by light microscopy of fluorescein-stained preparations from bone marrow at 24 and 48 h postdose.

Preclinical pharmacokinetics and toxicokinetics.

The comparative (rat, dog, and cynomolgus monkey) experiment was used to define pharmacokinetic parameters for laboratory animals. Calculation of the maximum concentration of a drug in serum (Cmax) and time to Cmax (Tmax) was achieved by the use of standard formulas applied to values derived with the concentrations of EMV measured in plasma as described earlier. Values for the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) were calculated by extrapolating the measured concentrations in plasma to infinity (AUC∞) and applying the trapeziodal rule. Bioavailability in rats was calculated from the ratios of AUC values to doses for the various dose routes (oral, intrarectal, and intra-portal vein) compared to the AUC for the intravenous dose of EMV and is expressed as percent bioavailability.

Toxicokinetic analyses were conducted with the concentrations of EMV for each individual monkey and for the groups of rats and mice in the toxicology experiments. The model-independent determinations of Cmax, Tmax, and AUC from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) were calculated with WinNonlin Professional software (version 1.5; Scientific Consulting, Inc., Cary, N.C.). Scheduled protocol times were used for the analyses. AUC values were determined by the linear-trapezoidal-rule method and extrapolated for daily exposures (AUC0–24) and are expressed as microgram-hours per milliliter.

RESULTS

Cytotoxicity.

Bone marrow toxicity has been associated with certain nucleoside analogs. Since EMV contains a substituted nucleobase, we examined the effect of the compound on bone marrow progenitor cells (Table 3). The results of these experiments demonstrated that EMV did not cause significant cytotoxicity compared with AZT (positive control). EMV was determined to have 50% cytotoxic concentrations of 30 and 50 μM for the erythroid (BFU-E) and granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM) progenitor cells, respectively. In these experiments AZT gave 50% cytotoxic concentrations of <0.1 μM for the BFU-E progenitor cells and 7 μM for the CFU-GM progenitor cells.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of AZT and EMV cytotoxicities on human bone marrow progenitor cells

| Compound | Concentration (μM) | % Survivala of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BFU-E | CFU-GM | ||

| None | 100 | 100 | |

| AZT | 0.1 | 46.4 ± 5.0 | 76.6 ± 6.6 |

| 1 | 34.8 ± 4.5 | 71.0 ± 6.0 | |

| 10 | 16.1 ± 5.2 | 41.0 ± 3.9 | |

| 100 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 11.3 ± 3.0 | |

| EMV | 0.1 | 92.3 ± 4.9 | 93.6 ± 3.7 |

| 1 | 83.3 ± 10.6 | 91.6 ± 5.6 | |

| 10 | 68.9 ± 8.9 | 81.6 ± 9.4 | |

| 100 | 22.9 ± 8.4 | 26.8 ± 4.1 | |

Values are from three separate experiments. Data are mean percent ± SD.

Mitochondrial toxicity.

The effect of EMV on mitochondrial functions was examined in exponentially growing HepG2 cells (Table 4). After the HepG2 cells were incubated with EMV at concentrations of 0.1 to 10 μM, no effect on cell growth, lactic acid production, mitochondrial DNA synthesis, or mitochondrial structure was seen compared to what occurred with untreated HepG2 cells.

TABLE 4.

Mitochondrial function in HepG2 cells exposed in vitro to EMVa

| EMV concn (μM) | Cell density (104/ml)b | l-Lactate (mg/104 cells)b | Mitochondrial DNA (% of control DNA)b | Lipid droplet formation | Mitochondrial morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 2.46 ± 0.05 | 100 | None | Normal |

| 0.1 | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 2.49 ± 0.06 | 104 ± 12 | NDc | ND |

| 1.0 | 15.9 ± 0.3 | 2.48 ± 0.04 | 98 ± 9 | ND | ND |

| 10 | 15.9 ± 0.6 | 2.50 ± 0.07 | 96 ± 11 | None | Normal |

Cells were exposed to EMV for 4 to 14 days.

Values are means ± SD of results from three separate experiments.

ND, not determined.

Preclinical pharmacokinetics and toxicokinetics.

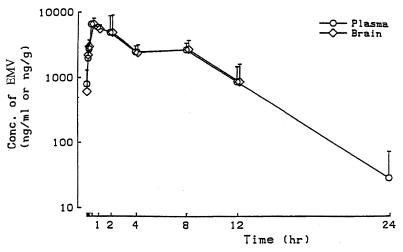

Pharmacokinetic experiments identified rats and monkeys as appropriate for toxicology experiments (Table 5). In dogs, levels of EMV in plasma declined rapidly and were undetectable by 1 h postdose. Autoradiography demonstrated that [14C]EMV was widely distributed to tissues of rats given 10 mg/kg by gavage, and at 0.5 h postdose, radioactivity was noted in all tissues, including brain and spinal cord. At 96 h postdose, radioactivity was detected only in the contents of the gastrointestinal tract. The total excretion of EMV was 99% of the administered dose, with 38% of the radioactivity being excreted into urine and 61% being excreted into feces. In the rat biliary excretion experiment, 25% of the administered EMV was excreted into bile at 1 h postdose; 75% was excreted into bile after 8 h. At 48 h postdose, 87, 11, and 2% of the labeled compound was found in the bile, urine, and feces, respectively. In a separate experiment, concentrations of EMV in brains from rats given a dose of 250 mg/kg by gavage were the same as those in plasma over the interval of 0.5 to 12 h postdose (Fig. 2).

TABLE 5.

Average pharmacokinetic parameters for monkeys, rats, and dogs given an oral dose of EMV

| Species (n) | Dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (ng/ml) | Tmax (h) | AUC (ng · h/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat (5) | 50 | 3,090 | 0.25 | 5,064a |

| Monkey (4) | 50 | 60 | 1.0 | 935a |

| Dog (4) | 10 | 54 | 1.0 | 109b |

AUC0–∞.

AUC0–8.

FIG. 2.

Plasma and brain EMV concentrations in rats. Rats were given an oral dose of EMV (250 mg/kg of body weight). Plasma and brain tissues were collected at the time intervals indicated, the latter being homogenized in 1.15% KCl. EMV was extracted, and concentrations were measured by an HPLC assay described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) (number of mice/group, 4). Conc., concentration.

When rats were given EMV by gavage, by intrarectal infusion, intravenously, and by infusion into the hepatic portal vein, the oral absorption was 68%, but the data (Table 6) indicated that first-pass hepatic metabolism accounted for the lower oral bioavailability of 18%. The experiment with rats given EMV for 14 days showed that there was induction of hepatic microsomal drug-metabolizing enzymes (Table 7). At 150 mg kg−1 day−1, the relative weight of the liver was significantly increased (4.3 g/100 g of body weight, compared to 3.9 g for controls and 5.4 g for rats given 80 mg of phenobarbitol kg−1 day−1). Cytochrome P450 content increased with increasing doses of EMV, starting with 0.9 ± 0.1 nmol/mg of protein (control), and reached significance at the high dose, 1.4 ± 0.2 nmol/mg of protein (P < 0.01 relative to the value for the control). Significant increases in the activity of 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylase occurred at all doses of EMV (Table 7) compared to the activity in the control. Phenobarbital had positive responses for the parameters measured, as expected (Table 7).

TABLE 6.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of EMV in rat plasma

| Route of administration | Dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (ng/ml) | Tmax (h) | AUC0–∞ (ng · h/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous | 0.88 | 265 | ||

| Oral | 5 | 154 | 0.25 | 277 |

| Intrarectal | 5 | 397 | 0.25 | 826 |

| Intra-portal vein | 0.25 | 20.5 |

TABLE 7.

Liver enzyme activities in male rats treated orally with EMV for 14 days

| Exptl groupa | Mean enzyme activity (nmol min−1 mg of protein−1) ± SDb of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADPH-cytochrome c reductase | Aniline hydroxylase | Aminopyrine N-demethylase | 7-Ethoxycoumarin O-demethylase | p-Nitrophenol UDP-glucuronyl transferase | |

| Vehicle | 90 ± 8 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 3.02 ± 0.44 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 8 ± 2 |

| EMV at: | |||||

| 15 mg kg−1 day−1 | 91 ± 9 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 3.55 ± 0.35 | 0.09 ± 0.01* | 12 ± 3 |

| 50 mg kg−1 day−1 | 94 ± 12 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 3.68 ± 0.70 | 0.11 ± 0.01** | 9 ± 4 |

| 150 mg kg−1 day−1 | 88 ± 13 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 3.98 ± 0.49 | 0.14 ± 0.02** | 11 ± 1 |

| PB at 80 mg kg−1 day−1 | 123 ± 11*** | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 3.28 ± 0.49 | 0.24 ± 0.04*** | 10 ± 1 |

Number of animals per group, 4 to 5. PB, reference compound phenobarbital.

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, significantly different from the value obtained with the vehicle by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's test; ***, P < 0.01, significantly different from the value obtained with the vehicle by Student's t test.

In vitro metabolism.

When liver microsomes from rats, cynomolgus monkeys, and humans were incubated with EMV, the relative affinities of the drug (at 3 μM) for the microsomes were greater for humans than rats but greater for monkeys than humans while the Km/Vmax values were greater for rats than monkeys but significantly greater for humans than rats (Table 8), suggesting a much slower metabolism of EMV in humans. This was confirmed with additional in vitro experiments where human liver microsomes formed only about a third (8 nmol) of the total EMV metabolites measured for microsomes from rats (24 nmol) and monkeys (26 nmol) after 60 min of incubation under identical conditions. These in vitro experiments also showed that three putative metabolites, detected with m/z of 319, 245, and 261 by MS, were produced (although their identities have not yet been confirmed) by the three species, but in differing proportions. In the rat and monkey, 65% of the total metabolites formed was that with the m/z of 245, tentatively identified as BIU. The other two metabolites were approximately equal in amount. In contrast, that with an m/z of 319 was the predominant metabolite in human microsomes, accounting for 54% of the total metabolites measured, followed by the putative metabolite BIU (37%). The three species formed the m/z-319 and -261 metabolites at similar rates, but at 60 min, the rat and monkey microsomes had produced five times more BIU than the human samples. Comparison with results of standard cytochrome P450-associated reactions, such as testosterone 6β-hydroxylation for cytochrome P450 3A4 or -5, and inhibition experiments with nifedipine and troleandomycin showed that, in humans, EMV was metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzymes 3A4 and 3A5. However, at low, pharmacologic concentrations (10 μM) of EMV, 40% of the total BIU formed in human microsomes was not abolished by troleandomycin, a cytochrome P450 3A4- and P3A5-specific inhibitor. Coupled with the results of the correlation analysis of cytochrome P450 1A2 activity (7-ethoxyresorufin O-dealkylase) in the individual human samples, this result suggested that in humans, the formation of BIU was catalyzed, in part, by cytochrome P450 1A2. We then observed that furafylline, a cytochrome P450 1A2-specific inhibitor, inhibited BIU formation in human microsomes treated with 10 μM EMV by approximately 50%, without affecting the formation of the other two major metabolites.

TABLE 8.

Comparison of EMV Km and Vmax values obtained with liver microsomes from three speciesa

| Species (n = 4) | Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol min−1 mg of protein−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Human | 69.9 ± 15.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Monkey | 9.8 ± 4.2 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Rat | 28.7 ± 2.6 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

Values shown are means ± SD.

Safety pharmacology experiments.

There were no important or consistent pharmacologic effects of EMV in the wide variety of safety pharmacology experiments performed. A significant increase in the duration of anesthesia produced by hexobarbital was observed in mice given an oral dose at 300 mg/kg but not at 100 mg/kg. Similarly, EMV accelerated intestinal transit in mice at 300 mg/kg per os but not at 100 mg/kg. There was no effect on respiration rate, blood pressure, heart rate, or electrocardiographs in anesthetized dogs given EMV at 300 mg/kg of body weight.

Toxicology experiments.

In single-dose experiments, the approximate lethal oral dose of EMV for rats was ≥3 g/kg for males and 2.5 g/kg for females. BIU, a putative metabolite of EMV, did not produce death in rats given a single oral dose of 3 g/kg, indicating that it was no more toxic than EMV. The 1-month experiment with rats identified 50 mg/kg/day as a no-effect dose where average peak levels of EMV in plasma were 3,090 ng/ml and the average AUC∞ was 5,064 ng · h/ml, as determined in the pharmacokinetic experiment. At the next dose level (150 mg/kg/day 4), decreased body weights, increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN), vacuoles in kidney tubules, increased serum alanine aminotransferase activity, and hepatocellular hypertrophy were observed in the animals. The livers were normal by histopathology. The 1-month experiment with monkeys identified a no-effect dose of 40 mg/kg/day where average peak values for plasma EMV ranged from 5 to 67 ng/ml and the AUC ranged from 30 to 412 ng · h/ml. Inconsistent emesis, mild diarrhea, and liver and kidney effects similar to those in rats were also observed in the monkeys at the next-highest dose, 200 mg/kg/day. At this dose, average peak values for EMV in plasma ranged from 30 to 170 ng/ml and the AUC0–24 ranged from 324 to 1,912 ng · h/ml.

The no-effect doses in the 3-month and chronic toxicity experiments were the same as those in the 1-month experiments with rats and monkeys, as shown in Table 2. Again, signs of toxicity at the higher doses were essentially limited to effects on the kidney as noted above. The kidneys were histologically normal, as were related laboratory values, at 4 weeks postdose in all of the toxicologic experiments. In the 1-year monkey experiment, emesis and diarrhea occurred at the high dose (180 mg/kg/day), but were mostly limited to the first five weeks of dosing. There were also increased values for BUN and creatinine, in addition to minor increases in alanine aminotransferase activities and insignificant decreases in erythrocyte counts. In the 1-year experiment, one of six high-dose male monkeys was necropsied when it was moribund at week 5. This animal had protracted diarrhea that was unresponsive to treatment. Histopathology defined moderate to severe enteritis as the cause of the diarrhea. Toxicity was sufficient in several of the animals in the high-dose group and in one monkey in the mid-dose group to require brief (1-week) interruptions of dosing in the second to fourth dose months. However, there was no further indication of toxicity at any dose after the effects described above resolved. Sperm counts and motility were normal in rats given EMV for 3 months in the chronic rat experiment. Nerve conduction velocities were measured in the chronic monkey experiment at 6 months and at 1 year and were unaffected by treatment with EMV.

Toxicokinetic analyses were consistent with the expected induction of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes in both rats and monkeys because the level of exposure to the drug at 1 week was greater than those measured at later time points. However, in all experiments, exposures were proportional to dose. In the 6-month rat experiment, exposures to EMV were comparable at both weeks 13 and 26, suggesting that autoinduction of drug-metabolizing enzymes had reached a plateau. In the case of rats at the high dose (160 mg of EMV/kg/day), the AUC0–24 for males averaged 2.6 μg · h/ml at week 13 while the corresponding value for females was 16.6 μg · h/ml. A sex difference was not noted in the three-month monkey experiment or in the 1-year monkey experiment. In those experiments, the 180-mg/kg/day EMV dose on day 2 resulted in an AUC0–24 value of 1.1 μg · h/ml for male monkeys and 0.9 μg · h/ml for females. Corresponding values for week 13 averaged 0.2 μg · h/ml for both male and female monkeys, again indicating enzyme induction and first-pass metabolism of EMV.

In the rat and rabbit developmental toxicology experiments, there was no indication of adverse effects on fetal development. However, at the high dose, 160 mg/kg/day, maternal toxicity was sufficient to produce abortion and death in rabbits. Fertility was normal at all doses of EMV (10, 40, and 160 mg/kg/day) in the rat fertility experiment. In the rat pre- and postnatal experiment, doses of 10 and 40 mg/kg/day were no-effect levels. At 160 mg/kg/day, maternal feed consumption and body weights were significantly decreased and body weights of the offspring were significantly lower than control values (P < 0.01 by Dunnett's test [8]) throughout the lactation period. However, all other parameters measured in the offspring such as activity, learning, memory, and reproductive function were unaffected by treatment of EMV regardless of the dose given. There was no indication of genotoxicity in any of the genetic toxicology experiments outlined above.

DISCUSSION

The chronic treatment of HIV-1 infection requires the availability of active, tolerable, safe, and conveniently administered agents for potent coactive regimens. EMV is an NNRTI derived from the HEPT chemical series of NNRTIs, which are among the most active in inhibiting the replication of HIV-1. Although EMV functions as an NNRTI, structurally it resembles an NRTI (12). In order to address the potential for NRTI-like toxicities (36), in vitro experiments using human bone marrow progenitor cells were performed. When compared with AZT, EMV had no effect on inhibiting growth of human bone marrow progenitor cells at concentrations that exceeded those measured in plasma in animals given doses of EMV that produced the kidney and gastrointestinal toxicities already described. EMV also demonstrated low cytotoxicity when it was compared with other anti-HIV agents such as saquinavir (7, 16). Recent reports have indicated that mitochondrial toxicity plays a major role in the adverse effects related to some nucleoside analogs (10), suggesting that nucleoside analogs under development should be evaluated for potential mitochondrial dysfunction. EMV had no effect on HepG2 cells treated with a 10 μM concentration of the drug for several days. When other nucleoside analogs were tested in HepG2 cells at this concentration, toxic effects such as increased lactic acid production (ranging from 13 to 79%) and mitochondria that were swollen or had loss of cristae were produced (10).

Monkeys were selected as the appropriate nonrodent toxicology model for several reasons. In pharmacokinetic experiments, the disappearance of EMV from plasma in monkeys was more gradual than in rats and much more gradual than in dogs. Thus, compared to dogs, monkeys would be more likely to achieve the exposure to EMV needed for adequate safety assessment. Dose-limiting neurological toxicities have been encountered with the clinical use of nucleoside analogs, most notably dideoxycytidine (6) and dideoxyinosine (24). Monkeys are a good model for studying potential effects of new antiviral drugs on the peripheral nervous system because noninvasive techniques to measure the conduction velocity in peripheral nerves exist. Indeed, these techniques were used in the chronic monkey experiment with EMV. Finally, the enzyme systems in monkeys and humans are very similar, including those that phosphorylate deoxynucleosides (18).

Since HIV-1 replication can occur not only in plasma but also in sanctuary sites such as the lymphoreticular system (15, 28) and the central nervous system (30), the ability of antiretroviral agents to distribute to these sites is desirable. To this aim, the tissue distribution of EMV was examined in rats following oral administration of 14C-labeled EMV. There was widespread whole-body distribution of radioactivity at 0.5 h postadministration that decreased to negligible levels by 24 and 96 h postadministration. Rats readily absorbed EMV and excreted it into bile. Moreover, EMV was able to cross the blood-brain barrier by 0.5 h after oral dosing. This ability is important because one limitation of many HIV therapies is the failure to distribute to the central nervous and lymphoreticular systems, where replication is known to occur (35). The penetration of EMV into cerebral spinal fluid in HIV-infected volunteers is under examination in clinical trials.

In vitro experiments with liver microsomes from rats, cynomolgus monkeys, and humans revealed that EMV was a substrate for metabolism by liver enzymes. These experiments demonstrated that human hepatic microsomes metabolize EMV more slowly than those from rat or monkey, producing, in aggregate, far less of the three putative EMV metabolites detected than was produced by the other two species. The cytochrome P450 isozymes 3A4 and 3A5 appeared to account for the majority of EMV microsomal metabolism, with 1A2 playing a role at therapeutic concentrations. This contribution from another P450 enzyme, depending on the substrate concentration, has been demonstrated with a protease inhibitor (9) and with diazepam (36). EMV induction of the latter enzyme, cytochrome P450 1A2, was supported by in vivo experiments where levels of 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylase activity were elevated in liver microsomes isolated from rats treated with EMV. The in vitro findings were also consistent with the observation of substantial first-pass hepatic metabolism in rats, in which a total oral bioavailability of 18% was observed, compared with an oral absorption of 68%. In addition, the observation that plasma EMV levels in the monkey toxicology experiments were higher at dose week 1 than at subsequent times most likely reflects the induction of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes.

The results of the acute, chronic, genetic, and reproductive toxicology experiments have demonstrated an attractive therapeutic opportunity for EMV. The only toxicity observed in the toxicology experiments involved the kidney and was reversible and limited to high doses of EMV. The association of this toxicity to EMV or to its metabolites was not determined. Hepatocellular hypertrophy, without increases in diagnostic liver enzymes or additional histopathologic alterations, was judged to be a functional change associated with the induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes in both rats and monkeys. The safety profile of EMV in all of these experiments supported the initial phase I administration of EMV to humans (C. P. Moxham, G. M. Szczech, M. R. Blum, and D. W. Barry, Program Abstr. 4th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunist. Infect., abstr. 573, 1997) and permitted selection of oral doses of EMV for use in that study. Since the no-effect level was 30 mg/kg/day in both the rat and monkey 1-month toxicology experiments, a dose 10-fold lower (3 mg/kg or 150 mg for a 50-kg patient) was selected as the starting dose for the clinical program with EMV. The safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics from a multiple-dose study (Moxham et al., 10th ICAR) have supported the continued clinical investigation of EMV.

The results from the reproductive toxicology experiments have further demonstrated a positive preclinical safety profile for EMV. With the exception of decreases in maternal and fetal body weights at the highest dose, 160 mg/kg/day, there was no effect of EMV on developmental or reproductive parameters. Given that women represent a growing percentage of the HIV-infected population, the ability to administer to them safe and effective treatments for HIV-1, without potential harm to their unborn children, is important. Pilot perinatal transmission studies to examine the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of EMV in pregnant women and their infants have been initiated based on data from our reproductive toxicology experiments (T. B. Grizzle, F. S. Rousseau, C. P. Moxham, and G. M. Szczech, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother, abstr. I-22, 1998). The toxicological data, as well as the clinical safety profile for adults, also give additional support for the study of pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, and activity of EMV as part of coactive therapy in children.

In conclusion, the extensive study of EMV in the preclinical setting and its favorable preclinical profile have supported the continued development of EMV. These data have allowed for development of EMV beyond the initial administration to humans to large-scale clinical trials with adults and to pilot phase II studies of children, women, and pregnant women. EMV is currently under active development to examine its utility in coactive regimens for the treatment of HIV-1 infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Peter L. Bullock, Phoenix International Life Sciences, Inc., Montreal, Canada, performed the reported in vitro experiments with the EMV metabolites. Donna T. Staton, Triangle Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Kerry-Ann da Costa, medical writer, Chapel Hill, N.C., provided expert technical assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames B N, Lee F D, Durston W E. An improved bacterial test system for the detection and classification of mutagens and carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:782–786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba M, DeClerq E, Iida S. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activities and pharmacokinetics of novel 6-substituted acyclouridine derivatives. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2358–2363. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.12.2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba M, Shigeta S, Yuasa S, Takashima H, Sekiya K, Ubasawa M, Tanaka H, Miyasaka T, Walker R T, De Clercq E. Preclinical evaluation of MKC-442, a highly potent and specific inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:688–692. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baba M, Yuasa S, Niwa T, Yamamoto M, Yabuuchi S, Takashima H, Ubasawa M, Tanaka H, Miyasaka T, Walker R T, Balzarini J, De Clercq E, Shigeta S. Effect of human serum on the in vitro anti HIV-1 activity of 1-[(2-hydroxyethoxy)methyl]-6-(phenylthio)-thymidine (HEPT) derivatives as related to their lipophilicity and serum protein binding. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:2507–2512. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90232-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balzarini J, Pelemans H, Perez-Perez M-J, San-Felix A, Camarasa M-J, De Clercq E, Karlsson A. Marked inhibitory activity of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 when combined with (−)2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:882–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger A R, Arezzo J C, Schaumburg H H, Skowron G, Merigan T, Bozzette S, Richman D, Soo W. 2′,3′-Dideoxycytidine (ddC) toxic neuropathy: a study of 52 patients. Neurology. 1993;43:358–362. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan T M, Taylor D L, Bridges C G, Leyda J P, Tyms A S. The inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vitro by a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, MKC-442, alone and in combination with other anti-HIV compounds. Antivir Res. 1995;26:173–187. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(94)00074-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruning J L, Kintz B L. Computational handbook of statistics. 3rd ed. Glenview, Ill: Harper Collins Publishers; 1987. Pearson product-moment correlation; pp. 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiba M, Hensleigh M, Nishime J, Balani S, Lin J. Role of cytochrome P450 3A4 in human metabolism of MK-639, a potent human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui L, Schinazi S, Gosselin G, Imbach J-L, Chu C K, Rando R F, Revankar G R, Sommadossi J-P. Effect of β enantiomeric and racemic nucleoside analogs on mitochondrial functions in HepG2 cells: implications for predicting drug hepatotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1577–1584. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Clerq E. HIV-1-specific RT inhibitors: highly selective inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that are specifically targeted at the viral reverse transcriptase. Med Res Rev. 1993;13:229–258. doi: 10.1002/med.2610130303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Clerq E. The role of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in the therapy of HIV-1 infection. Antivir Res. 1998;38:153–179. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Clerq E. What can be expected from non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infections? Med Virol. 1996;6:97–117. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199606)6:2<97::AID-RMV168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Clerq E, Balzarini J. Knocking out human immunodeficiency virus through non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors used as single agents or in combinations: a paradigm for the cure of AIDS? Il Pharmaco. 1995;50:735–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Embretson J, Zupancic M, Ribas J L, Burke A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Haase A T. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes and macrophages by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Nature. 1993;362:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furman P A, Moxham C. MKC-442: a potent and selective non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Drugs Future. 1998;23:718–724. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graul A, Rabasseda X, Castañer J. Efavirenz. Drugs Future. 1998;23:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habteyesus A, Nordenskjold A, Bohman C, Eriksson S. Deoxynucleoside phosphorylating enzymes in monkey and human tissues show great similarities, while mouse deoxycytidine kinase has a different substrate specificity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:1829–1836. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi M, Morita T, Kodama Y, Sofuni T, Ishidate M. The micronucleus assay with mouse peripheral blood reticulocytes using acridine orange-coated slides. Mutat Res. 1990;245:245–249. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(90)90153-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi S, Noshiro M, Okuda K. Isolation of a cytochrome P-450 that catalyzes the 25-hydroxylation of vitamin D3 from rat liver microsomes. J Biochem. 1986;99:1753–1763. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins A L, Jingshan R, Esnouf R M, Willcox B E, Yvonne Jones E, Ross C, Miyasaka T, Walker R T, Tanaka H, Stammers D K, Stuart D I. Complexes of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with inhibitors of the HEPT series reveal conformational changes relevant to the design of potent non-nucleoside inhibitors. J Med Chem. 1996;39:1589–1600. doi: 10.1021/jm960056x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilby J M, Saag M S. Is there a role for non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in the treatment of HIV infection? Infect Agents Dis. 1994;3:313–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li A P, Carver J H, Choy W N, Hsie A W, Gupta R S, Loveday K S, O'Neill J P, Riddle J C, Stankowski L F, Yang L L. A guide for the performance of the Chinese hamster ovary cell hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase gene mutation assay. Mutat Res. 1987;189:135. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(87)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaren C, Datema R, Knupp C A, Buroker R A. Review: didanosine. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1991;2:321–328. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merluzzi V J, Hargrave K D, Labadia M, Grozinger K, Skoog M, Wu J C, Shih C-K, Eckner K, Hattox S, Adams J, Rosehthal A S, Faanes R, Eckner R J, Koup R A, Sullivan J L. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Science. 1990;250:1411–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1701568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy R L, Montaner J. Nevirapine: a review of its development, pharmacological profile and potential for clinical use. Exp Opin Investig Drugs. 1996;5:1183–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamoto M, Makino M, Yamada K, Nakade K, Yuasa S, Baba M. Complete inhibition of viral breakthrough by combination of MKC-442 with AZT during a long-term culture of HIV-1-infected cells. Antivir Res. 1996;31:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(96)00946-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Demarest J F, Butini L, Montroni M, Fox C H, Orenstein J M, Kotler D P, Fauci A S. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature. 1993;362:355–358. doi: 10.1038/362355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel S S, Benfield P. Nevirapine. Clin Immunother. 1996;6:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pialoux G, Fournier S, Moulignier A, Poveda J-D, Clavel F, Dupont B. Central nervous system as a sanctuary for HIV-1 infection despite treatment with zidovudine, lamivudine and indinavir. AIDS. 1997;11:1302–1303. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199710001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piras G, Nakade K, Yuasa S, Baba M. Three-drug combinations of MKC-442, lamivudine, and zidovudine in vitro: potential approach towards effective chemotherapy against HIV-1. AIDS. 1997;11:469–475. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199704000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seki M, Sadakata Y, Yuasa S, Baba M. Isolation and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants resistant to the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor MKC-442. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1995;6:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sommadossi J-P, Carlisle R, Schinazi R F, Zhou Z. Uridine reverses the toxicity of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine in normal human granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells in vitro without impairment of antiretroviral activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:997–1001. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.7.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swindells S, Gundelman H E. The new non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Infect Med. 1996;13:715–719. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wie X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;273:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasumori T, Nagata K, Yang S, Chen L, Murayama N, Yamazoe Y, Kato R. Cytochrome P450 mediated metabolism of diazepam in human and rat: involvement of human CYP2C in N-demethylation in a substrate concentration-dependent manner. Pharmacogenetics. 1993;3:291–301. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuasa S, Sadakata Y, Takashima H, Kouichi S, Inouye N, Ubasawa M, Baba M. Selective and synergistic inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase by a non-nucleoside inhibitor, MKC-442. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:895–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]