Abstract

Background

The liver and bones are both active endocrine organs that carry out several metabolic functions. However, the link between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and bone mineral density (BMD) is still controversial. The goal of this study was to discover if there was a link between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and bone mineral density in US persons aged 20 to 59 years of different genders and races.

Methods

Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017–2018, multivariate logistic regression models were utilized to investigate the association between NAFLD and lumbar BMD. Fitted smoothing curves and generalized additive models were also used.

Results

The analysis included a total of 1980 adults. After controlling for various variables, we discovered that NAFLD was negatively linked with lumbar BMD. The favorable connection of NAFLD with lumbar BMD was maintained in subgroup analyses stratified by sex, race and age in men, other race and aged 20-29 years. The relationship between NAFLD and lumbar BMD in blacks and people aged 40-49 years was a U-shaped curve with the inflection point: at 236dB/m and 262dB/m. Furthermore, we discovered that liver advanced fibrosis and liver cirrhosis were independently connected with higher BMD, while no significant differences were detected in severe liver steatosis and BMD.

Conclusions

Our study found an independently unfavorable relationship between NAFLD and BMD in persons aged 20 to 59. We also discovered a positive link between BMD and advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. More research is needed to back up the findings of this study and to look into the underlying issues.

Keywords: bone mineral density, osteoporosis, NHANES, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cross-sectional study, hepatic steatosis

Background

Osteoporosis is a long-term disorder marked by reduced bone mineral density (BMD) that affects a huge number of people (1). According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation, more than 30 percent of women and more than 20 percent of men over the age of 50 have osteoporosis or osteopenia, putting them at risk for osteoporotic fractures (2). Simultaneously, the prevalence of osteoporosis continues to climb as the population ages and expands (3). Apart from genetics, age, and gender, other variables that affect bone metabolisms, such as food intake and lifestyle, have lately received a lot of attention (4–6). Meanwhile, scientists are working to discover novel ways to prevent and treat osteoporosis.

NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) is the most common chronic liver disease and one of the leading causes of severe liver disease across the world. In the absence of severe alcohol consumption or secondary reasons, NAFLD is characterized as excessive fat infiltration into the liver. Currently, the prevalence in Asia is about one out of four people with NAFLD, which is comparable to many Western countries (7). In addition, a physically inactive lifestyle and a rising trend of metabolic diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and obesity are associated with the prevalence and development of NAFLD (8).

Both the bone and the liver are active endocrine organs with a variety of metabolic functions (9, 10). A growing body of research implies a relationship between NAFLD and low BMD (11–14). According to various studies, patients with NAFLD are more likely to have low BMD and an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures, and the underlying mechanism is convoluted and unknown (11). The occurrence of significant liver fibrosis as determined by vibration controlled and transient elastography (VCTE) was connected to poor BMD in NAFLD in a small number of studies (15). The link between low BMD and NAFLD has only been studied in a few large-scale longitudinal investigations. Furthermore, the mechanism underlying this is unknown, but Circulating molecules, insulin resistance, TNF-α and vitamin D insufficiency appear to be potential linkages (16). As a result, we assessed the connection of NAFLD with BMD in adults in this study using a comprehensive fraction of individuals aged 20 to 59 from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Population

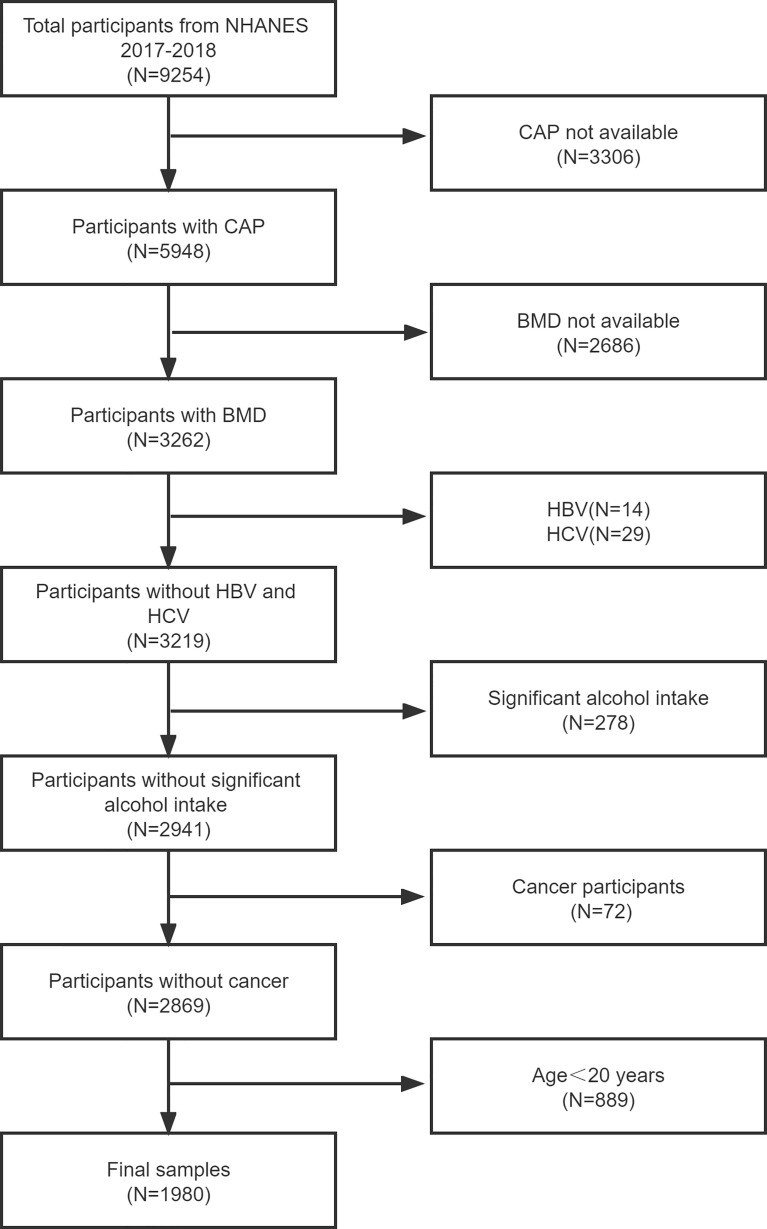

The NHANES is a major, continuing cross-sectional survey in the United States that aims to give objective statistics on health issues and address emerging public health concerns among the general public. The NHANES datasets were utilized for this investigation from 2017 to 2018. The participants in the research had to be between the ages of 20 and 59. Among the 1980 eligible adults, we excluded 3306 individuals with missing Median CAP data, 2686 with missing BMD data, 752 participants with significant alcohol consumption, 889 individuals younger than 20 years, 14 hepatitis B antigen-positive and 29 hepatitis C antibody-positive or hepatitis C RNA-positive samples, and 72 individuals with cancer diagnoses. Finally, 1980 people were enrolled in the study. Finally, 1980 people were enrolled in the study ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants selection. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; BMD, bone mineral density; hepatitis B virus, HBV; hepatitis C virus, HCV.

Ethics Statement

The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board authorized the protocols for the NHANES and got signed informed consent. After anonymization, the NHANES data is available to the public. This enables academics to transform data into a study-able format. We agree to follow the study’s data usage guidelines to guarantee that data is only utilized for statistical analysis and that all experiments are carried out in compliance with applicable standards and regulations.

Study Variables

Clinicians use VCTE as a noninvasive approach to determine the prevalence and severity of NAFLD in clinical practice, and it has been found to be trustworthy. NHANES staff used FibroScan® model 502 V2 Touch equipped to conduct VCTE evaluations on participants throughout the 2017-2018 period. According to a recent landmark study, controlled attenuation parameter values, which also be called CAP, ≥274 dB/m was considered suggestive of NAFLD status since had 90% sensitivity in detecting all degrees of liver steatosis (17). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was performed using a Hologic QDR 4500A device and Apex software version 3.2 by qualified radiology technologists to assess lumbar BMD. Covariates in multivariate models may cause the correlations between urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites and lumbar BMD to be muddled. Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, diabetes status, waist circumference, Glycated hemoglobin, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were all covariates in this study. The NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/) has a thorough explanation of how these variables are calculated.

Statistical Analysis

We used R (http://www.r-project.org) and EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com) for all statistical analyses, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Because the goal of NHANES is to produce data that is representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized population in the United States, all estimates were calculated using sample weights in accordance with NCHS’s analytical guidelines. Model 1 had no variables adjusted, model 2 had age, gender, and race adjusted, and model 3 had all of the covariates listed in Table 1 adjusted. There were also subgroup analyses performed. A weighted generalized additive model and smooth curve fitting were employed to deal with non-linearity.

Table 1.

Weighted characteristics of the study population based on CAP.

| Non-NAFLD | NAFLD | Severe steatosis | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CAP<274, n = 1210) | (274≤CAP<302, n = 281) | (CAP≥302, n = 489) | ||

| Age (years) | 36.835 ± 11.891 | 40.665 ± 11.886 | 41.183 ± 10.901 | <0.00001 |

| Gender (%) | <0.00001 | |||

| Male | 44.600 | 53.731 | 61.260 | |

| Female | 55.400 | 46.269 | 38.740 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | <0.00001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 57.645 | 48.903 | 56.806 | |

| Non- Hispanic Black | 13.689 | 11.455 | 9.606 | |

| Mexican American | 7.567 | 15.343 | 14.303 | |

| Other Race | 21.099 | 24.300 | 19.285 | |

| Diabetes (%) | <0.00001 | |||

| Yes | 1.735 | 5.032 | 11.909 | |

| No | 98.265 | 94.968 | 88.091 | |

| Moderate activities | 0.09520 | |||

| Yes | 52.879 | 49.436 | 49.004 | |

| No | 47.121 | 50.564 | 50.996 | |

| Smoke at least 100 cigarettes | 0.30105 | |||

| Yes | 32.692 | 33.267 | 33.097 | |

| No | 67.308 | 66.733 | 66.903 | |

| Broken or fractured a hip | 0.54585 | |||

| Yes | 0.327 | 1.328 | 0.368 | |

| No | 99.673 | 98.672 | 99.632 | |

| Broken or fractured a wrist | 0.03451 | |||

| Yes | 17.919 | 11.184 | 8.346 | |

| No | 82.081 | 88.816 | 91.654 | |

| Broken or fractured spine | 0.73514 | |||

| Yes | 4.079 | 3.601 | 1.686 | |

| No | 95.921 | 96.399 | 98.314 | |

| Ever taken prednisone or cortisone daily | 0.39680 | |||

| Yes | 10.170 | 8.125 | 5.263 | |

| No | 89.830 | 91.875 | 94.737 | |

| Income to poverty ratio | 3.063 ± 1.659 | 3.069 ± 1.601 | 2.995 ± 1.591 | 0.74727 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.484 ± 5.634 | 30.883 ± 5.703 | 34.975 ± 7.195 | <0.00001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.845 ± 14.221 | 102.653 ± 12.657 | 112.635 ± 15.418 | <0.00001 |

| Laboratory features | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.327 ± 0.552 | 5.624 ± 0.907 | 5.842 ± 1.061 | <0.00001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.753 ± 0.953 | 4.965 ± 0.965 | 5.049 ± 0.935 | <0.00001 |

| Triglyceride(mmol/L) | 1.015 ± 0.658 | 1.647 ± 1.629 | 1.921 ± 1.709 | <0.00001 |

| LDL- cholesterol(mmol/L) | 2.787 ± 0.853 | 2.976 ± 0.909 | 3.055 ± 0.833 | 0.00022 |

| HDL- cholesterol(mmol/L) | 1.467 ± 0.382 | 1.270 ± 0.367 | 1.190 ± 0.305 | <0.00001 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 19.855 ± 13.137 | 26.308 ± 17.980 | 31.708 ± 22.117 | <0.00001 |

| AST (IU/L) | 21.072 ± 11.305 | 21.365 ± 8.724 | 24.567 ± 13.545 | <0.00001 |

| ALP(IU/L) | 71.010 ± 22.289 | 75.605 ± 19.544 | 78.627 ± 21.957 | <0.00001 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 23.071 ± 26.912 | 31.363 ± 30.740 | 37.902 ± 34.435 | <0.00001 |

| Serum creatinine (umol/L) | 75.129 ± 17.899 | 75.437 ± 20.164 | 75.237 ± 18.139 | 0.77658 |

| Serum iron(umol/L) | 17.028 ± 7.614 | 15.618 ± 5.559 | 15.196 ± 5.879 | <0.00001 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 217.329 ± 36.446 | 287.384 ± 7.872 | 341.624 ± 30.199 | <0.00001 |

| LSM (kPa) | 4.676 ± 1.981 | 6.121 ± 6.987 | 7.500 ± 8.264 | <0.00001 |

| Lumbar bone mineral density (g/cm2) | 1.058 ± 0.151 | 1.034 ± 0.137 | 1.039 ± 0.150 | 0.00935 |

Mean+SD for continuous variables: P value was calculated by weighted linear regression model.

% for Categorical variables: P value was calculated by weighted chi-square test.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The demographic and laboratory data of the participants (1210 Non-NAFLD, 281 NAFLD and 489 Severe steatosis) are presented in Table 1 . Compared to Non-NAFLD participants, NAFLD participants and Severe steatosis participants were more likely to be male, Mexican American, and diabetic populations. Participants with NAFLD and Severe steatosis had significantly higher BMI, waist circumference and higher wrist fractured rate, and significantly higher levels of Glycated hemoglobin, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, CAP, and LSM, while HDL- cholesterol, and Serum iron, and Lumbar bone mineral density were lower. The weighted characteristics of the study population based on LSM are shown in Table S1 .

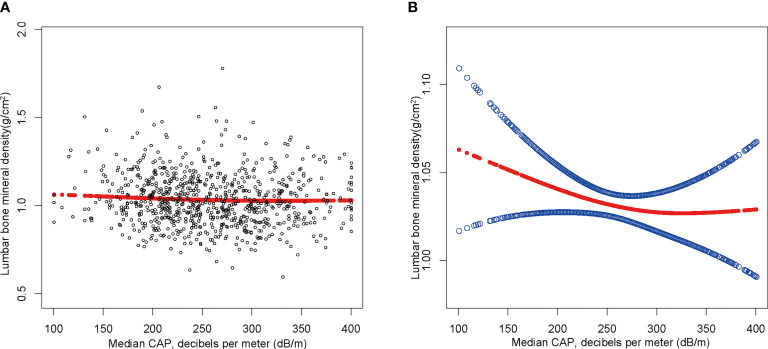

Relationship Between NAFLD and BMD

The findings of the multivariate regression analysis are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2 . NAFLD was negatively linked with lumbar BMD in the unadjusted model [-0.022 (-0.035, -0.008)]. However, this significant correlation becomes insignificant after adjusting for the covariates in Model 2[-0.012 (-0.026, 0.001)] and Model 3[-0.013 (-0.049, 0.023)]. With the point of inflection discovered by two-piecewise linear regression model, at 367(dB/m) ( Table 5 ).

Table 2.

Association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density (g/cm2) stratified by gender.

| Model 1:β(95% CI), p | Model 2:β(95% CI), p | Model 3:β(95% CI), p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.022 (-0.035, -0.008) 0.00206 | -0.012 (-0.026, 0.001) 0.07913 | -0.039 (-0.081, 0.003) 0.07250 |

| Males | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.029 (-0.048, -0.009) 0.00495 | -0.020 (-0.040, 0.000) 0.05423 | -0.021 (-0.050, 0.062) 0.08322 |

| Females | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.014 (-0.033, 0.005) 0.15842 | -0.003 (-0.022, 0.016) 0.72778 | -0.017 (-0.052, 0.039) 0.06461 |

Model 1: No covariates were adjusted. Model 2: Age, gender, race were adjusted.

Model 3: Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, smoking behavior, Moderate activities, Diabetes status, Waist circumference, HbA1c (%), Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

*In the subgroup analysis stratified by gender or race, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable itself.

Figure 2.

The association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density. (A) Each black point represents a sample. (B) The solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit. Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, diabetes status, waist circumference, Glycated hemoglobin, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

Table 5.

Threshold effect analysis of NAFLD on lumbar bone mineral density using two-piecewise linear regression model.

| Lumbar bone mineral density | Adjusted β(95%CI) |

|---|---|

| P value | |

| NAFLD | |

| Inflection point | 367 |

| CAP<236(dB/m) | -0.000 (-0.000, 0.000) |

| 0.7497 | |

| CAP>236(dB/m) | 0.001 (-0.001, 0.003) |

| 0.3573 | |

| Log likelihood ratio | 0.342 |

| Non-Hispanic black | |

| Inflection point | 236 |

| CAP<236(dB/m) | -0.005 (-0.008, -0.001) |

| 0.0101 | |

| CAP>236(dB/m) | -0.000 (-0.001, 0.001) |

| 0.8620 | |

| Log likelihood ratio | 0.009 |

| Aged 40-49 | |

| Inflection point | 262 |

| CAP<262(dB/m) | 0.000 (-0.000, 0.001) |

| 0.8448 | |

| CAP>262(dB/m) | -0.004 (-0.006, -0.001) |

| 0.0015 | |

| Log likelihood ratio | 0.028 |

Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, smoking behavior, Moderate activities, Diabetes status, Waist circumference, HbA1c (%), Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

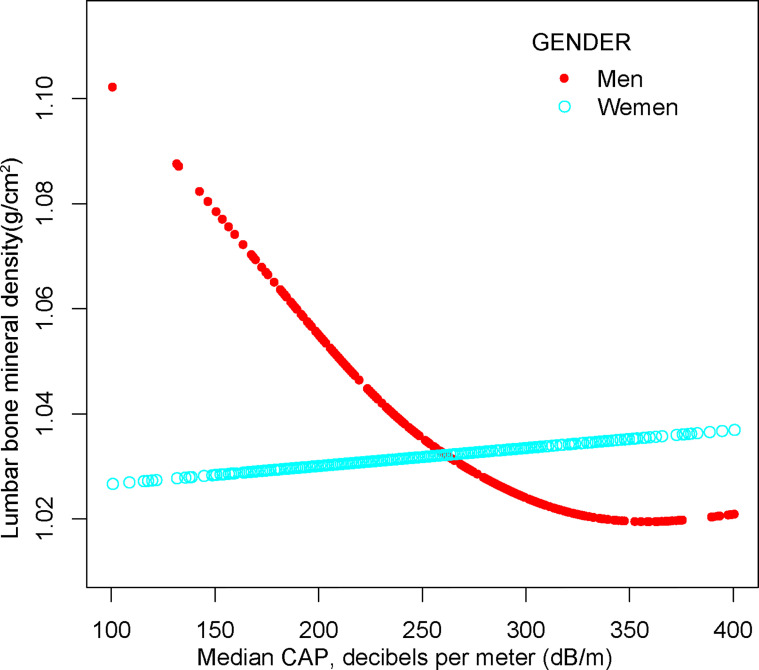

Subgroup Analysis

After adjusting for covariates, the results of subgroup analysis, smooth curve fittings and generalized additive models showed that the association among NAFLD and BMD was mainly present in males, other race and participants aged 20 to 29. Detailed information on the subgroup analysis is shown in Tables 2 – 4 .

Table 4.

Association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density (g/cm2) stratified by age.

| Age | Model 1:β(95% CI), p | Model 2:β(95% CI), p | Model 3:β(95% CI), p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (20-29) | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.064 (-0.089, -0.038) <0.00001 | -0.050 (-0.076, -0.025) 0.00013 | -0.051 (-0.139, 0.011) 0.05521 |

| Age (30-39) | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.017 (-0.041, 0.007) 0.17505 | -0.010 (-0.034, 0.015) 0.44259 | -0.028 (-0.078, 0.032) 0.63545 |

| Age (40-49) | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.008 (-0.037, 0.020) 0.56467 | -0.001 (-0.029, 0.027) 0.94431 | 0.020 (-0.055, 0.109) 0.62401 |

| Age (50-59) | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | 0.011 (-0.020, 0.042) | 0.004 (-0.028, 0.035) | 0.029 (-0.048, 0.107) |

| 0.49400 | 0.82339 | 0.45933 |

Model 1: No covariates were adjusted. Model 2: Age, gender, race were adjusted.

Model 3: Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, smoking behavior, Moderate activities, Diabetes status, Waist circumference, HbA1c (%), Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

*In the subgroup analysis stratified by gender or race, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable itself.

For males, NAFLD exhibited a significant inverse association with BMD in Model 1[-0.029 (-0.048, -0.009)], but not in Model 2[-0.020 (-0.040, 0.000)] and Model3[-0.004 (-0.060, 0.052)]. In addition, the nonlinear relationship was characterized by smooth curve fittings and generalized additive models ( Table 2 and Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

The association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density stratified by gender. Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, diabetes status, waist circumference, Glycated hemoglobin, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

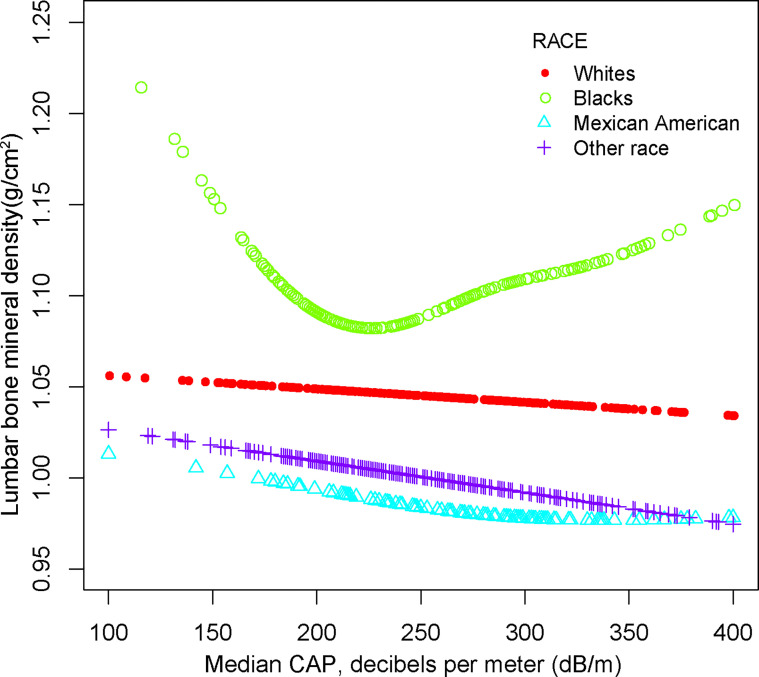

For other race, the adverse association as same as males in Model 1[-0.024 (-0.046, -0.003)], but not in Model 2[-0.012 (-0.026, 0.001)] and Model3[-0.013 (-0.049, 0.023)]. Of note, when stratified by race, we found a U-shape relationship between NAFLD and BMD in blacks ( Table 3 and Figure 4 ). With the point of inflection discovered by two-piecewise linear regression model, at 236(dB/m) ( Table 5 ).

Table 3.

Association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density (g/cm2) stratified by race.

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | Model 1:β(95% CI), p | Model 2:β(95% CI), p | Model 3:β(95% CI), p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.013 (-0.039, 0.013) 0.32101 | -0.008 (-0.035, 0.018) 0.54638 | -0.016 (-0.082, 0.042) 0.51292 |

| Non- Hispanic Black | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.005 (-0.039, 0.030) 0.77792 | 0.003 (-0.033, 0.038) | 0.030 (-0.078, 0.118) |

| 0.88626 | 0.46515 | ||

| Mexican American | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.021 (-0.049, 0.006) 0.12916 | -0.021 (-0.049, 0.007) 0.14525 | -0.041 (-0.128, 0.011) 0.31224 |

| Other Race | |||

| Non-NAFLD | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NAFLD | -0.024 (-0.046, -0.003) 0.02556 | -0.012 (-0.026, 0.001) 0.07913 | -0.011 (-0.090, 0.068) 0.78868 |

Model 1: No covariates were adjusted. Model 2: Age, gender, race were adjusted.

Model 3: Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, smoking behavior, Moderate activities, Diabetes status, Waist circumference, HbA1c (%), Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

*In the subgroup analysis stratified by gender or race, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable itself.

Figure 4.

The association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density stratified by race. Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, diabetes status, waist circumference, Glycated hemoglobin, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

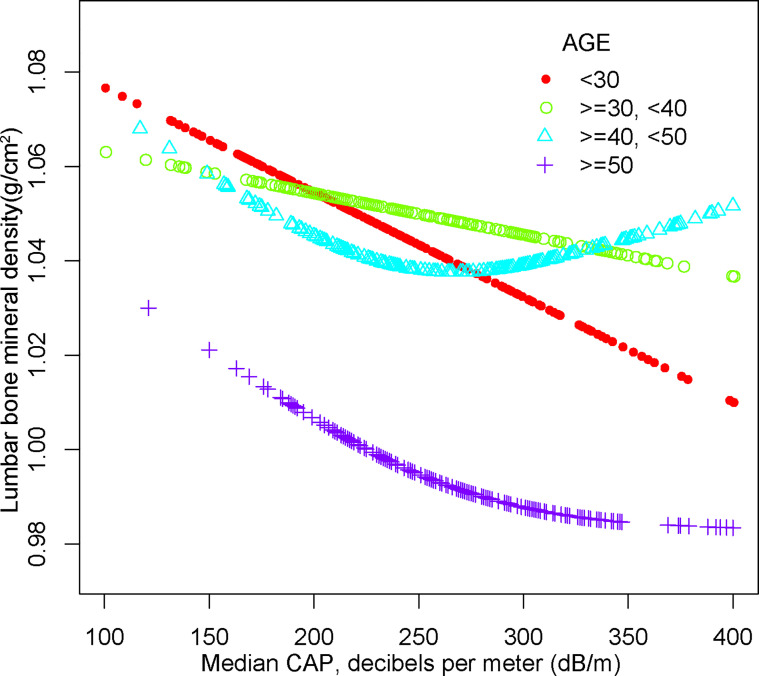

For people aged 20-29, there is a significant negative association with NAFLD and BMD in Model 1[-0.064 (-0.089, -0.038)], Model 2[-0.050 (-0.076, -0.025)] but not in Model3[-0.058 (-0.119, 0.003)]. Furthermore, we found a U-shape relationship between NAFLD and BMD in people aged 40-49 years, when stratified by age in Table 4 and Figure 5 . With the point of inflection identified using a two-piecewise linear regression model, at 262(dB/m) ( Table 5 ).

Figure 5.

The association between NAFLD and lumbar bone mineral density stratified by age. Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, diabetes status, waist circumference, Glycated hemoglobin, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

Relationship Between Degree of Hepatic Steatosis and BMD

We further investigated the connection among degree of hepatic steatosis and BMD in adults with NAFLD, we found a significant positive association between advanced liver fibrosis and BMD in Model1[-0.064 (-0.089, -0.038)], Model2[-0.064 (-0.089, -0.038)] but not in Model3[-0.064 (-0.089, -0.038)]. And there is a significant positive association between liver cirrhosis and BMD in Model1[0.067 (0.021, 0.112)], Model2[0.068 (0.024, 0.112)] and Model3[0.153 (0.032, 0.274)]. However, no significant differences were found in severe liver steatosis with BMD as well as Significant liver fibrosis with BMD. Table 6 provide more details on the subgroup analysis.

Table 6.

Association between degree of hepatic steatosis and lumbar bone mineral density (g/cm2).

| Exposure | Model 1:β(95% CI), p | Model 2:β(95% CI), p | Model 3:β(95% CI), p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe steatosis | |||

| CAP<302 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| CAP≥302 (n = 489) | -0.015 (-0.030, 0.001) 0.05991 | -0.008 (-0.023, 0.008) 0.33794 | -0.020 (-0.051, 0.020) 0.35510 |

| Significant fibrosis | |||

| LSM<8.0 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| LSM≥8.0 (n = 59) | 0.011 (-0.015, 0.037) | 0.013 (-0.013, 0.039) | -0.013 (-0.065, 0.046) 0.78231 |

| 0.40881 | 0.31822 | ||

| Advanced fibrosis | |||

| LSM<9.7 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| LSM≥9.7 (n = 39) | 0.049 (0.014, 0.084) | 0.051 (0.017, 0.086) | 0.059 (-0.054, 0.101) |

| 0.00631 | 0.00367 | 0.13638 | |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| LSM<13.6 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| LSM≥13.6 (n = 33) | 0.067 (0.021, 0.112) | 0.068 (0.024, 0.112) | 0.150 (0.031, 0.264) |

| 0.00387 | 0.00256 | 0.02010 |

Model 1: No covariates were adjusted. Model 2: Age, gender, race were adjusted.

Model 3: Age, gender, race, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, education, smoking behavior, Moderate activities, Diabetes status, Waist circumference, HbA1c (%), Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST, Serum creatinine, Serum iron, Lumbar bone mineral density, CAP and LSM were adjusted.

*In the subgroup analysis stratified by gender or race, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable itself.

Discussion

In this study of individuals aged 20-59 years, we demonstrated the negative association between NAFLD and BMD. In addition, on subgroup analysis, however, we discovered a U-shaped relationship among other studies of NAFLD and BMD in other races and people aged 20-29. Moreover, based on the non-invasive fibrosis markers, we found a positive correlation between BMD and Advanced fibrosis and Cirrhosis.

Clinical studies on the relationship between NAFLD and BMD in adults are still inconclusive. And the majority of these epidemiological studies are centered on Asian and menopausal female populations, with only a handful focusing on European and American males. There was no notable change in BMD among patients with NAFLD and controls, according to a recent meta-analysis of five cross-sectional studies (18). NAFLD was likewise linked to self-reported osteoporotic fractures in the other meta-analysis, but not to poor BMD (14). Other studies, on the other hand, refuted this conclusion. The findings of cohort research involving 4318 Chinese with NAFLD and 17,272 Chinese without NAFLD revealed that NAFLD may enhance the risk of new-onset osteoporosis (19). A Korean cross-sectional study of 3739 premenopausal women discovered a negative link between NAFLD and BMD (12). Other Korean and Chinese cross-sectional investigations backed up the same conclusion (20–24), as well as a cohort study from America (25). NAFLD was strongly connected to an increased risk of low BMD in men but not in women, and in other race but not in whites, blacks, or Mexican Americans, according to our findings. According to previous studies, NAFLD is a hermaphroditic dimorphic condition that is more frequent in males and postmenopausal women, whereas inadequate bone mineral density is more frequent in postmenopausal women (26, 27). However, there are few studies on racial differences in NAFLD and BMD and further epidemiological studies based on racial stratification analysis are needed to clarify the causes.

Clinical investigations on the link between steatosis severity and BMD are scarce and controversial. Kim et al. discovered that substantial liver fibrosis as measured by hepatic transient elastography is independently linked with low BMD in a cross-sectional study of 231 asymptomatic Korean participants (15). A new study in NAFLDs looked at the relationship between liver fibrosis and BMD (28). They discovered that NAFLD-related hepatic fibrosis was linked to lower BMD in postmenopausal women with T2DM or IGR. According to a remarkable study (17), severe steatosis defined as CAP ≥ 302, advanced fibrosis defined as LSM ≥ 9.7 kPa, and cirrhosis defined as LSM ≥ 13.6 kPa were noticed. We investigated the association between steatosis severity and BMD by this definition (29). In contrast to previous findings, we discovered that liver advanced fibrosis and liver cirrhosis were independently connected with higher BMD, while no significant differences were detected in severe liver steatosis and BMD.

The mechanisms behind the relationship between NAFLD and BMD are unclear. There are various probable causes for this phenomenon, according to relevant studies. NAFLD can worsen insulin resistance and trigger the production of a slew of pro-inflammatory cytokines and bone-influencing molecules, all of which can contribute to bone demineralization and osteoporosis (30, 31). In addition to this, there is growing evidence that NAFLD causes alterations in the production of several molecular coordinators that may be detrimental to bone health, such as overproduction of TNF-a (32) and deficiencies in vitamin D (33), osteopontin (34) and osteoprotegerin (35). Moreover, circulating molecules may have different effects on bone metabolism by affecting early childhood obesity (36) or the progression of NAFLD (37). However, it is reasonable to believe that increased body weight is a prevalent trait of people with NAFLD (38), may help to prevent bone loss by increasing mechanical loads and improving cortical bone growth. Observations in people with obesity or type 2 diabetes are similar (39). Long-term fracture risk in patients with NAFLD may be underestimated by BMD values alone. It is conceivable to assume, based on the findings of this study, that NAFLD may have a sex-related differential influence on fracture risk. However, given that an increased risk of self-reported osteoporotic fractures among patients with NAFLD has only been seen in two cross-sectional studies conducted in China, it is still unclear if these findings can be generalized to other ethnic communities (22, 23). Furthermore, sex hormone levels and body fat deposition might be plausible causes for the discrepancies between men and women. In postmenopausal women, estrogen insufficiency is believed to be the leading cause of low bone mineral density (40, 41). Estrogen works to retain bone mass by reducing bone resorption by regulating osteoclast activity through the estrogen receptor (42, 43). NAFLD and the effect of estrogen insufficiency in women may contribute to the development of low BMD in an additive or synergistic manner. More research is needed to properly understand the function of NAFLD in the development of bone loss, taking into account the fact that various effects exist depending on gender. However, we feel that further prospective studies and mechanistic research are needed to better understand this crucial subject, particularly in non-Asian populations.

Most cohort and cross-sectional research have focused on postmenopausal women and Asians to yet. Little is known regarding the relationship between NAFLD and BMD in non-Asian, younger populations. Our findings are extremely relevant to the entire population since we used a nationally representative sample. We were also able to undertake subgroup analyses of NAFLD and lumbar spine BMD across gender and ethnicity, and evaluate the relationship between the degree of hepatic steatosis and bone mineral density, thanks to our large sample size. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the study’s limitations. First, our study’s cross-sectional design makes it hard to conclude a causal association between NAFLD and lumbar BMD in adults. To understand the specific mechanism of the relationship between NAFLD and BMD, further fundamental mechanistic research and large sample prospective studies are required. Second, NAFLD was diagnosed based on vibration controlled and transient elastography, which may have understated the prevalence of the disease. Third, the part of missing data from the NHANES database 2017-2018 on the usage of medication, history of fracture that can alter BMD could have skewed the results. Fourth, due to the limitations of the NHANES database, we were unable to obtain data on T score or Z score, which could also affect our assessment of the participants’ osteoporosis.

Conclusion

Our study found an independently unfavorable relationship between NAFLD and lumbar BMD in persons aged 20 to 59. This connection followed a U-shaped pattern among blacks and persons aged 40-49 years. We also discovered a positive link between BMD and advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Our findings may provide insight into prospective osteoporosis preventative and treatment approaches. More high-quality prospective studies are needed to corroborate or refute our findings on this research issue, as well as a more in-depth analysis of gender and ethnic disparities.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

RX and ML designed the research. RX collected, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. RX and ML revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study Funded by the Scientific Research Project of Hunan Health and Family Planning Commission to ML (A2017018).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.857110/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

NAFLD, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; BMD, bone mineral density; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; VCTE, vibration controlled and transient elastography; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; BMI, body mass index.

References

- 1. Ensrud K, Crandall C. Osteoporosis. Ann Internal Med (2017) 167:ITC17–32. doi: 10.7326/AITC201708010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright N, Looker A, Saag K, Curtis J, Delzell E, Randall S, et al. The Recent Prevalence of Osteoporosis and Low Bone Mass in the United States Based on Bone Mineral Density at the Femoral Neck or Lumbar Spine. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res (2014) 29:2520–6. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alejandro P, Constantinescu F. A Review of Osteoporosis in the Older Adult: An Update. Rheum Dis Clinics North Am (2018) 44:437–51. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nomura S, Kitami A, Takao-Kawabata R, Takakura A, Nakatsugawa M, Kono R, et al. Teriparatide Improves Bone and Lipid Metabolism in a Male Rat Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrinology (2019) 160:2339–52. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gajewska J, Weker H, Ambroszkiewicz J, Szamotulska K, Chełchowska M, Franek E, et al. Alterations in Markers of Bone Metabolism and Adipokines Following a 3-Month Lifestyle Intervention Induced Weight Loss in Obese Prepubertal Children. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes: Off J German Soc Endocrinol German Diabetes Assoc (2013) 121:498–504. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1347198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Villareal D, Shah K, Banks M, Sinacore D, Klein S. Effect of Weight Loss and Exercise Therapy on Bone Metabolism and Mass in Obese Older Adults: A One-Year Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2008) 93:2181–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fan J, Kim S, Wong V. New Trends on Obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J Hepatol (2017) 67:862–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farrell G, Wong V, Chitturi S. NAFLD in Asia–as Common and Important as in the West. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2013) 10:307–18. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. VanWagner L, Rinella M. Extrahepatic Manifestations of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr Hepatol Rep (2016) 15:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s11901-016-0295-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiGirolamo D, Clemens T, Kousteni S. The Skeleton as an Endocrine Organ. Nat Rev Rheumatol (2012) 8:674–83. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pardee P, Dunn W, Schwimmer J. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease is Associated With Low Bone Mineral Density in Obese Children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2012) 35:248–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04924.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee D, Park J, Hur K, Um S. Association Between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women. Climacteric: J Int Menopause Soc (2018) 21:498–501. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2018.1481380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Umehara T. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Elevated Alanine Aminotransferase Levels is Negatively Associated With Bone Mineral Density: Cross-Sectional Study in U.S. Adults. PloS One (2018) 13:e0197900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mantovani A, Gatti D, Zoppini G, Lippi G, Bonora E, Byrne C, et al. Association Between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Reduced Bone Mineral Density in Children: A Meta-Analysis. Hepatol (Baltimore Md.) (2019) 70:812–23. doi: 10.1002/hep.30538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim G, Kim K, Rhee Y, Lim S. Significant Liver Fibrosis Assessed Using Liver Transient Elastography is Independently Associated With Low Bone Mineral Density in Patients With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PloS One (2017) 12:e0182202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Targher G, Lonardo A, Rossini M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Decreased Bone Mineral Density: Is There a Link? J Endocrinol Invest (2015) 38:817–25. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0315-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eddowes P, Sasso M, Allison M, Tsochatzis E, Anstee Q, Sheridan D, et al. Accuracy of FibroScan Controlled Attenuation Parameter and Liver Stiffness Measurement in Assessing Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology (2019) 156:1717–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Upala S, Jaruvongvanich V, Wijarnpreecha K, Sanguankeo A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Osteoporosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Bone Miner Metab (2017) 35:685–93. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0807-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen H, Yang H, Hsueh K, Shen C, Chen R, Yu H, et al. Increased Risk of Osteoporosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicine (2018) 97:e12835. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahn S, Seo D, Kim S, Nam M, Hong S. The Relationship Between Fatty Liver Index and Bone Mineral Density in Koreans: KNHANES 2010-2011. Osteoporos Int: J Established Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA (2018) 29:181–90. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4257-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen D, Xu Q, Wu X, Cai C, Zhang L, Shi K, et al. The Combined Effect of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Metabolic Syndrome on Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Females in Eastern China. Int J Endocrinol (2018) 2018:2314769. doi: 10.1155/2018/2314769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cui R, Sheng H, Rui X, Cheng X, Sheng C, Wang J, et al. Low Bone Mineral Density in Chinese Adults With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Endocrinol (2013) 2013:396545. doi: 10.1155/2013/396545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Y, Wen G, Zhou R, Zhong W, Lu S, Hu C, et al. Association of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Osteoporotic Fractures: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study of Chinese Individuals. Front Endocrinol (2018) 9:408. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang H, Shim S, Ma B, Kwak J. Association of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Bone Mineral Density and Serum Osteocalcin Levels in Korean Men. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2016) 28:338–44. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shen Z, Cen L, Chen X, Pan J, Li Y, Chen W, et al. Increased Risk of Low Bone Mineral Density in Patients With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cohort Study. Eur J Endocrinol (2020) 182:157–64. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Filip R, Radzki R, Bieńko M. Novel Insights Into the Relationship Between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Osteoporosis. Clin Interventions Aging (2018) 13:1879–91. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S170533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ballestri S, Nascimbeni F, Baldelli E, Marrazzo A, Romagnoli D, Lonardo A. NAFLD as a Sexual Dimorphic Disease: Role of Gender and Reproductive Status in the Development and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Inherent Cardiovascular Risk. Adv Ther (2017) 34:1291–326. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0556-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhu X, Yan H, Chang X, Xia M, Zhang L, Wang L, et al. Association Between Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-Associated Hepatic Fibrosis and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women With Type 2 Diabetes or Impaired Glucose Regulation. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care (2020) 8:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ciardullo S, Perseghin G. Statin Use is Associated With Lower Prevalence of Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Metabol: Clin Exp (2021) 121:154752. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yilmaz Y. Review Article: Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Osteoporosis–Clinical and Molecular Crosstalk. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2012) 36:345–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guañabens N, Parés A. Osteoporosis in Chronic Liver Disease. Liver Int: Off J Int Assoc Study Liver (2018) 38:776–85. doi: 10.1111/liv.13730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zou W, Hakim I, Tschoep K, Endres S, Bar-Shavit Z. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Mediates RANK Ligand Stimulation of Osteoclast Differentiation by an Autocrine Mechanism. J Cell Biochem (2001) 83:70–83. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chun L, Yu E, Sawh M, Bross C, Nichols J, Polgreen L, et al. Hepatic Steatosis is Negatively Associated With Bone Mineral Density in Children. J Pediatr (2021) 233:105–11.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Syn W, Choi S, Liaskou E, Karaca G, Agboola K, Oo Y, et al. Osteopontin is Induced by Hedgehog Pathway Activation and Promotes Fibrosis Progression in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatol (Baltimore Md.) (2011) 53:106–15. doi: 10.1002/hep.23998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yilmaz Y, Yonal O, Kurt R, Oral A, Eren F, Ozdogan O, et al. Serum Levels of Osteoprotegerin in the Spectrum of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest (2010) 70:541–6. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2010.524933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iacomino G, Russo P, Marena P, Lauria F, Venezia A, Ahrens W, et al. Circulating microRNAs are Associated With Early Childhood Obesity: Results of the I.Family Study. Genes Nutr (2019) 14:2. doi: 10.1186/s12263-018-0622-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnson K, Leary P, Govaere O, Barter M, Charlton S, Cockell S, et al. Increased Serum miR-193a-5p During Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Progression: Diagnostic and Mechanistic Relevance. JHEP Rep: Innovation Hepatol (2022) 4:100409. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Younossi Z, Anstee Q, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global Burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, Predictions, Risk Factors and Prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2018) 15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Keefe J, Bhatti S, Patil H, DiNicolantonio J, Lucan S, Lavie C. Effects of Habitual Coffee Consumption on Cardiometabolic Disease, Cardiovascular Health, and All-Cause Mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol (2013) 62:1043–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moon S, Lee Y, Kim S. Association of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Low Bone Mass in Postmenopausal Women. Endocrine (2012) 42:423–9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9639-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xia M, Lin H, Yan H, Bian H, Chang X, Zhang L, et al. The Association of Liver Fat Content and Serum Alanine Aminotransferase With Bone Mineral Density in Middle-Aged and Elderly Chinese Men and Postmenopausal Women. J Trans Med (2016) 14:11. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0766-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Melville K, Kelly N, Khan S, Schimenti J, Ross F, Main R, et al. Female Mice Lacking Estrogen Receptor-Alpha in Osteoblasts Have Compromised Bone Mass and Strength. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res (2014) 29:370–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kodama I, Niida S, Sanada M, Yoshiko Y, Tsuda M, Maeda N, et al. Estrogen Regulates the Production of VEGF for Osteoclast Formation and Activity in Op/Op Mice. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res (2004) 19:200–6. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.