Abstract

We have studied the in vivo activity of the new experimental triazole derivative SCH 56592 (posaconazole) against a variety of strains of the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas' disease, in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed murine hosts. The T. cruzi strains used in the study were previously characterized as susceptible (CL), partially resistant (Y), or highly resistant (Colombiana, SC-28, and VL-10) to the drugs currently in clinical use, nifurtimox and benznidazole. Furthermore, all strains are completely resistant to conventional antifungal azoles, such as ketoconazole. In the first study, acute infections with the CL, Y, and Colombiana strains in both normal and cyclophosphamide-immunosuppressed mice were treated orally, starting 4 days postinfection (p.i.), for 20 consecutive daily doses. The results indicated that in immunocompetent animals SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg of body weight/day provided protection (80 to 90%) against death caused by all strains, a level comparable or superior to that provided by the optimal dose of benznidazole (100 mg/kg/day). Evaluation of parasitological cure revealed that SCH 56592 was able to cure 90 to 100% of the surviving animals infected with the CL and Y strains and 50% of those which received the benznidazole- and nifurtimox-resistant Colombiana strain. Immunosuppression markedly reduced the mean survival time of untreated mice infected with any of the strains, but this was not observed for the groups which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day or benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day. However, the overall cure rates were higher for animals treated with SCH 56592 than among those treated with benznidazole. The results were confirmed in a second study, using the same model but a longer (43-dose) treatment period. Finally, a model for the chronic disease in which oral treatment was started 120 days p.i. and consisted of 20 daily consecutive doses was investigated. The results showed that SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day was able to induce a statistically significant increase in survival of animals infected with all strains, while benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day was able to increase survival only in animals infected with the Colombiana strain. Moreover, the triazole was able to induce parasitological cures in 50 to 60% of surviving animals, irrespective of the infecting strain, while no cures were obtained with benznidazole. Taken together, the results demonstrate that SCH 56592 has in vivo trypanocidal activity, even against T. cruzi strains naturally resistant to nitrofurans, nitroimidazoles, and conventional antifungal azoles, and that this activity is retained to a large extent in immunosuppressed hosts.

Chemotherapy of Chagas' disease (American trypanosomiasis), a parasitic disease caused by the kinetoplastid protozoan Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi which afflicts 16 to 18 million people in Latin America, remains an enormous scientific and social challenge, as the drugs currently available, nitrofurans (nifurtimox; Bayer) and nitroimidazoles (benznidazole; Roche, São Paulo, Brazil), have little or no activity in the prevalent chronic form of the disease and can also produce serious toxic effects in the host (7, 8, 24, 26). Like many fungi and yeasts, T. cruzi has a strict requirement of specific endogenous sterols for cell viability and growth and is extremely sensitive to sterol biosynthesis inhibitors in vitro (13, 16, 29, 31–33, 35, 36). However, currently available sterol biosynthesis inhibitors, which are highly successful in the treatment of fungal diseases, are not powerful enough to eradicate T. cruzi from experimentally infected animals or human patients (3, 18, 20). Recent work from our laboratories has shown that new azole derivatives (inhibitors of fungal cytochrome P-450-dependent C14 sterol demethylase), such as D0870 (Zeneca Pharmaceuticals) and SCH 56592 (Schering-Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, N.J.), are capable of inducing parasitological cures in murine models of both acute and chronic Chagas' disease (13, 29, 30, 33, 34) and are the first compounds ever to display such activity. It has been shown that this special antiparasitic activity results from the potent and selective anti-T. cruzi activity and special pharmacokinetic properties of these compounds, particularly their long terminal half-lives and large volumes of distribution (13, 29, 30, 33, 34). Although the development of D0870 has recently been discontinued, numerous studies have consistently shown that SCH 56592 has a potent and broad-spectrum antifungal activity in vivo and is well tolerated in a variety of animal models and in humans (6, 12, 14, 15, 21–23, 28; R. Petraitiene, V. Petraitis, A. Groll, M. Candelario, A. Field-Ridley, T. Sien, R. L. Schaufele, J. Bacher, and T. J. Walsh, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., p. 582, abstr. 2004, 1999; M. A. Pfaller, I. Zerva, S. A. Messer, and R. N. Jones, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F87, 1996; D. Skiest, D. Ward, A. Northland, J. Reynes, and W. Greaves, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., p. 491, abstr. 1162, 1999). Our recent studies with this compound (33) have shown that it is the most potent sterol biosynthesis and antiproliferative agent ever tested against T. cruzi, making it an attractive candidate for the treatment of human Chagas' disease.

It has been known for a number of years that T. cruzi strains differ widely in terms of their biological properties as well as their susceptibility to nitrofurans and nitroimidazoles (2). Filardi and Brener (10), in a study of a large number of clinical and natural isolates from different geographical areas, found three main groups characterized as susceptible, partially drug resistant, and highly drug resistant. Both nitrofuran/nitroimidazole-susceptible and -resistant strains have recently been shown to be resistant in vivo to conventional antifungal azoles, such as ketoconazole, also an inhibitor of the parasite's C14 sterol demethylase (1). In this work, as in a previous study (10), a strain is defined as resistant to a given drug if the drug is unable to induce a parasitological cure with an experimental protocol (inoculum, dose and duration of treatment) which produces sterilization of animals infected with reference (susceptible) strains.

Many studies have also been devoted to the characterization of the role of the immune system in the resistance of vertebrate hosts, including humans, to T. cruzi and its involvement in the pathogenesis of Chagas' disease, particularly in its chronic form (4, 25, 30). The crucial role of the immune system in the maintenance of the host-parasite balance in the indeterminate phase of Chagas' disease has been highlighted recently by reports of dramatic reactivation phenomena observed in chronic chagasic patients immunosuppressed due to AIDS or pharmacological intervention (9, 27). Finally, recent studies have demonstrated the participation of stimulatory cytokines such as gamma interferon or interleukin-12 (IL-12) in the antiparasitic activity of benznidazole in murine models of acute Chagas' disease (19).

In the present study we investigated the in vivo activity of SCH 56592 against a series of T. cruzi strains selected from among those previously characterized by Filardi and Brener (10) in a variety of murine models, including immunosuppressed hosts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

The CL, Y, Colombiana, SC-28, and VL-10 strains were previously characterized (10); the original isolates have been maintained as trypomastigotes in liquid nitrogen, periodically transferred to mice, and refrozen, with full retention of their biological and drug resistance characteristics. Handling of live T. cruzi was done according to established guidelines (11).

Models of acute infection.

The protocol developed by Filardi and Brener (10) was followed for studies of acute infections. Briefly, groups of 10 immunocompetent or immunosuppressed (see below) outbred female Swiss albino mice, weighing 18 to 20 g, were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 104 blood trypomastigotes of the different strains; oral treatment was initiated 4 days postinfection (p.i.) and given daily for a total of 20 doses. Surviving animals were monitored for 60 days. In a second study, normal (immunocompetent) animals were infected with the same inoculum (104) and treatment was started at 4 days p.i. but given daily for 28 days, followed by a 7-day rest and another 15 days of treatment (16, 29, 32–35). Surviving animals were monitored for up to 113 days p.i. SCH 56592 was suspended in aqueous 2% methylcellulose plus 0.5% Tween 80, while benznidazole was dissolved in water containing 1% arabic gum; both drugs were given by gavage. Control (untreated) animals received the vehicle as a placebo, which had no detectable toxic effects.

Model of chronic infection.

Outbred female Swiss albino mice weighing 18 to 20 g were inoculated i.p. with 30 blood trypomastigotes of the different strains to allow the development of a chronic, latent infection. After 120 days, surviving animals with no circulating parasites were randomly divided into different treatment groups (12 animals per group) and subjected to oral treatment for 20 consecutive days, as described above. Surviving animals were monitored for up to 191 days p.i.

Parasitological and serological tests.

Parasitemia was measured in a hemacytometer with tail blood. Hemocultures were carried out by inoculating 5 ml of liver infusion medium with 0.2 to 0.4 ml of blood obtained from the orbital sinuses of experimental animals. Cultures were incubated without agitation at 28°C and examined for the presence of proliferative epimastigote forms at 30 and 60 days. Xenodiagnosis was done with 10 second-stage Rodnius prolixus and Triatoma infectans nymphs per mouse; 30 to 40 days after feeding, the insect feces were analyzed for T. cruzi metacyclic forms. Antibodies against live T. cruzi were evaluated by the procedure of Martins-Filho et al. (17), with minor modifications. Briefly, 5 × 105 live trypomastigotes were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the presence of different dilutions (1:1,500 to 1:3,000) of serum from experimental animals. The parasites were then washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark in the presence of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody solution (Sigma Immunochemical Reagents, St. Louis, Mo.), diluted 200-fold with PBS containing 10% FBS. Each assay included a control in which parasites were not exposed to mouse serum but were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. FITC-labeled parasites were washed once with PBS containing 10% FBS and fixed at 4°C with FACS FIX solution (1% [wt/vol] paraformaldehyde, 0.01% sodium azide, 1% sodium cacodylate [pH 7.2]). Labeled parasites were analyzed by cytofluorometry in a Becton Dickinson FACScan interfaced to a digital Micro HP 9153C as described before (17).

Statistical analysis.

The Kaplan-Meier nonparametric method was used to estimate the survival functions of the different experimental groups and rank tests (log-rank and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon) were used to compare them. The analyses were done with the Survival Tools package for StatView 4.5 run on a Power Macintosh 6500/250 computer.

Immunosuppression.

Animals were immunosuppressed by treatment with two doses of cyclophosphamide given i.p. at 50 mg/kg of body weight/day 2 days and 1 day before infection.

Drugs.

SCH 56592 {posaconazole, (−)-4-[4-[4-[4-[[(2R-cis)-5-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-tetrahydro-5-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl)furan-3-yl]methoxy]phenyl]- 2,4-dihydro-2-[(S)-1-ethyl-2(S)-hydroxypropyl]-3H-1,2,4-triazol-3-one} (Fig. 1) was provided by Schering Plough Research Institute. Benznidazole (Rochagan) was a product of Roche.

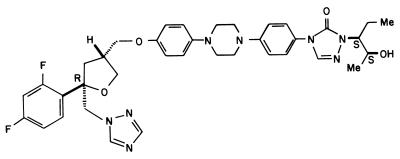

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of SCH 56592 (posaconazole).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effects of SCH 56592 on acute experimental infections caused by drug-resistant T. cruzi strains in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed mice.

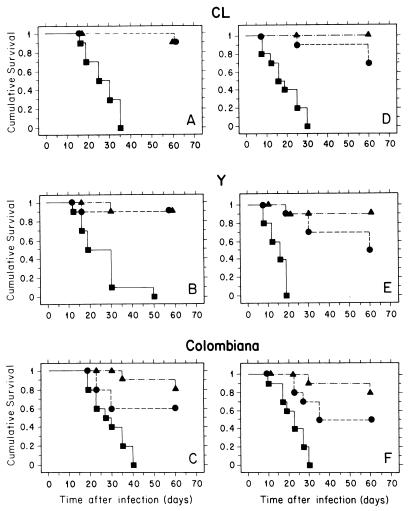

In our initial studies, a murine model of acute Chagas' disease previously designed to characterize drug resistance among different T. cruzi strains (10) was used. In this protocol mice were infected with 104 bloodstream trypomastigotes of different T. cruzi strains; oral treatment was started 4 days p.i. and given daily for 20 consecutive days. As can be seen in Fig. 2, with this protocol SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day provided a high level of protection (80 to 90%) against death, which was comparable (CL and Y strains) or superior (Colombiana strain) to that observed with benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day, which is the optimal dose of this drug (10). Highly significant statistical differences in survival were obtained between control (untreated) and both drug-treated groups (P values in log-rank and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon tests were ≤0.0001 and ≤0.0002 for SCH 56592 and ≤0.01 and ≤0.03 for benznidazole, respectively). Parasitological cures in surviving animals were verified by three independent criteria: hemoculture, xenodiagnosis, and the presence of anti-live T. cruzi antibodies, detected by flow cytometry (17). Results are presented in Table 1. Against the CL strain, which is susceptible to nifurtimox and benznidazole (10) but resistant to ketoconazole at doses as high as 120 mg/kg/day (1), SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day was able to cure 100% of the surviving animals; this high cure rate was, as expected, comparable to that obtained with benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day. For the Y strain, previously characterized as partially resistant to nitrofurans and nitroimidazoles but completely resistant to ketoconazole (1, 10), benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day was able to cure less than 50% of the surviving animals while the cure rate for animals which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day approached 90%. For the Colombiana strain, benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day was unable to induce parasitological cures, in agreement with previous results (10), but 50% of the surviving animals which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day were cured. This is the first report of such a high level of parasitological cure in experimental infections with drug-resistant T. cruzi strains. These results show that the mechanisms of resistance against benznidazole, nifurtimox, and conventional azoles in T. cruzi are much less effective against recently developed triazoles, which are inhibitors of C14 sterol demethylase; this fact could be explained by a higher affinity of the latter to their biochemical target (D. Sanglard, F. Ischer, J. Bille, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C-11, 1997) and/or the differential interaction of the drugs with the cell's detoxifying systems.

FIG. 2.

Effects of SCH 56592 and benznidazole treatment on survival of immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts in a murine model of acute Chagas' disease. Immunocompetent (A to C) and immunosuppressed (D to F) female albino Swiss mice were each challenged with 104 blood trypomastigotes of the CL (A and D), Y (B and E), or Colombiana (C and F) strain, and oral treatment was initiated 4 days p.i. for a total of 20 daily consecutive doses. Each experimental group contained 10 animals. Symbols: ■, control (untreated) animals; ▴, animals which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day; ●, animals which received benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day. Statistical analyses of the survival plots were carried out using both the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon tests. For details, see the text.

TABLE 1.

Effects of SCH 56592 and benznidazole in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed murine models of acute Chagas' disease with different strains of T. cruzi

| Strain | Immunosuppression | No. of negative mice/no. testeda

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (untreated) | Benznidazole (100 mg/kg/day) | SCH 56592 (20 mg/kg/day) | ||

| CL | No | 0/10 | 9/9 | 9/9 |

| CL | Yes | 0/10 | 6/7 | 10/10 |

| Y | No | 0/10 | 4/9 | 8/9 |

| Y | Yes | 0/10 | 3/5 | 4/9 |

| Colombiana | No | 0/10 | 0/6 | 4/8 |

| Colombiana | Yes | 0/10 | 1/5 | 3/8 |

Female albino Swiss mice were inoculated with 104 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the indicated strain, and treatment was started 4 days p.i. The drugs were given orally for 20 days. Survival was monitored daily for 60 days p.i. Parasitological cure of animals which survived until the end of the observation period was assessed by hemoculture, xenodiagnosis, and flow cytometry analysis for anti-live T. cruzi antibodies. Animals were considered cured when all three tests were negative (for details see Materials and Methods).

To evaluate the role of the immune system in the antiparasitic activity of benznidazole and SCH 56592, mice were immunosuppressed by treatment with 50 mg of cyclophosphamide per kg during two consecutive days previous to infection; animals were then infected and given antiparasitic treatment as described above for normal (immunocompetent) animals. Figure 2 shows survival plots for the different experimental groups. It was found that immunosuppression led to a significant (P ≤ 0.04 [log-rank test] in all cases) reduction in the mean survival time for all strains (mean survival times for control and immunosuppressed animals were 26.9 and 18.9 days, 25.2 and 14.8 days, and 29.1 and 22.3 days for the CL, Y, and Colombiana strains, respectively). Nevertheless, as in immunocompetent animals, there were very significant differences in survival between control and drug-treated groups (P values in log-rank and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon tests of ≤0.0001 and 0.0002 for SCH 56592 and 0.001 and 0.003 for benznidazole, respectively), while there were no significant differences in survival between immunocompetent and immunosuppressed animals which received either drug treatment. For all strains, survival levels for immunosuppressed animals which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day were higher than those for mice receiving benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day, but there was no statistically significant difference between data for the two drugs. These results clearly show that both drugs can protect from a lethal parasitic infection, even in the presence of a severe immunosuppression.

Evaluation of the parasitological cure (Table 1) revealed that, while immunosuppression did not affect significantly the level of cures induced by SCH 56592 in animals infected with the susceptible CL or drug-resistant Colombiana strain, it had a significant effect in animals infected with the partially drug-resistant Y strain (Table 1). However, even in immunosuppressed animals, the overall cure rates for animals infected with the Y or Colombiana strain and treated with the triazole remained higher than values for those treated with benznidazole. These results indicate that the potent anti-T. cruzi effects of SCH 56592 against the Y strain in normal hosts are partially dependent on cooperation from the immune system but also that its trypanocidal activity is higher than that of benznidazole even in immunosuppressed animals. Recent studies have demonstrated that early activation of the immune system by cytokines such as IL-12 may be involved in the trypanocidal activity of benznidazole in acute murine infections with T. cruzi (19). The results described above suggest that the anti-T. cruzi effects of SCH 56592 may be further enhanced when it is used in combination with IL-12 and related cytokines.

In a second set of experiments the same acute model was used but with a longer treatment course, starting 4 days p.i. and given daily for 28 consecutive days followed by a 7-day rest and another 15 days of treatment, for a total of 43 doses. This course of treatment was used in our previous studies that first demonstrated the in vivo trypanocidal effects of both D0870 and SCH 56592 (13, 16, 32–35). In addition, other T. cruzi strains (SC-28 and VL-10, both nifurtimox and benznidazole resistant [10]) were included in the study. As shown in Table 2, with this protocol SCH 56592 given at ≥10 mg/kg/day was able to induce very high (90 to 100%) survival levels for all strains, comparable or superior to those obtained with benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day. It can be seen in Table 3 that SCH 56592 at just 5 mg/kg/day produced levels of parasitological cures which were comparable to those obtained with benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day, but when the triazole was given at 20 mg/kg/day, cure rates reached 80 to 100% in survivors infected with the susceptible and partially drug-resistant strains and 55 to 100% in those infected with the drug-resistant strains. The results confirmed those of the initial study and demonstrated that SCH 56592 can eliminate both susceptible and drug-resistant parasite populations from murine hosts.

TABLE 2.

Effects of SCH 56592 and benznidazole in a murine model of acute Chagas' disease with different strains of T. cruzi

| Strain | No. of survivors/total no. receivinga:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drug (control) | Benznidazole, 100 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 5 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 10 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 20 mg/kg/day | |

| CL | 0/10 | 9/10 | 6/10 | 9/10 | 9/10 |

| Y | 0/10 | 8/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 | 9/10 |

| Colombiana | 0/10 | 6/10 | 9/10 | 9/10 | 8/10 |

| SC-28 | 0/10 | 7/10 | 9/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 |

| VL-10 | 0/10 | 7/10 | 4/10 | 10/10 | 9/10 |

Female albino Swiss mice (18 to 20 g) were inoculated with 104 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the indicated strain, and treatment was started 4 days p.i. The drugs were given orally for 28 days, followed by a 7-day rest and another 15 days of treatment. Animals were monitored for 113 days p.i.

TABLE 3.

Effects of SCH 56592 and benznidazole in a murine model of acute Chagas' disease with different strains of T. cruzi

| Strain | No. of negative mice/no. testeda

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (untreated) | Benznidazole, 100 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 5 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 10 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 20 mg/kg/day | |

| CL | 0/10 | 9/9 | 6/6 | 9/9 | 9/9 |

| Y | 0/10 | 4/8 | 5/9 | 6/10 | 7/9 |

| Colombiana | 0/10 | 3/6 | 5/9 | 4/9 | 6/8 |

| SC-28 | 0/10 | 2/7 | 5/9 | 6/9 | 8/8 |

| VL-10 | 0/10 | 1/7 | 2/4 | 3/10 | 5/9 |

Female albino Swiss mice (18 to 20 g) were inoculated with 104 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the indicated strain, and treatment was started 4 days p.i. The drugs were given orally for 28 days, followed by a 7-day rest and another 15 days of treatment. Parasitological cure of animals which survived until the end of the observation period (113 days p.i.) was assessed by hemoculture, xenodiagnosis, and flow cytometry analysis for anti-live T. cruzi antibodies. Animals were considered cured when all three tests were negative (for details see Materials and Methods).

In vivo activity of SCH 56592 and benznidazole in a murine model of chronic Chagas' disease with different T. cruzi strains.

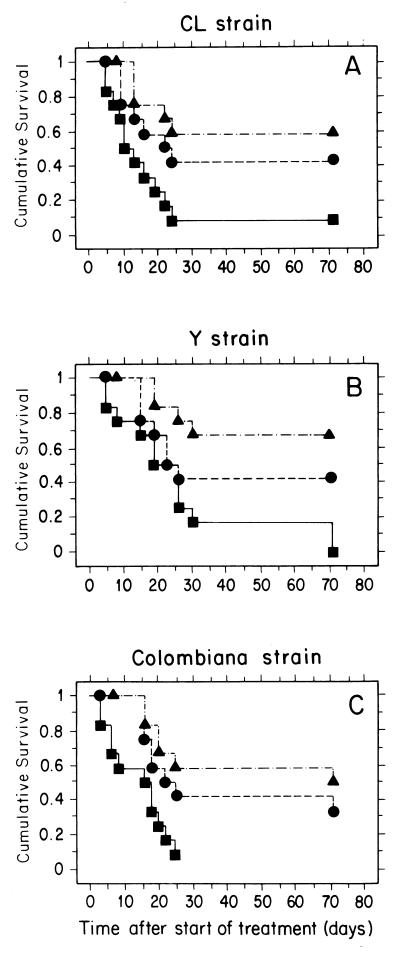

In a third model of infection, mice were infected with a small inoculum of blood trypomastigotes (30 per animal) of the CL, Y, or Colombiana strain, which led to a more controlled infection and higher survival levels. Animals that survived after 120 days and had developed a chronic, latent infection with no circulating parasites were treated orally with the short (20 consecutive daily doses) protocol described above. As shown in Fig. 3, for all strains, animals which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day had survival curves with highly significant statistical differences from curves for untreated controls (P values for both log-rank and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon tests of ≤0.0035) while for those receiving benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day, statistically significant differences were only observed with the Colombiana strain (P values for both log-rank and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon tests of ≤0.03). Table 4 shows that SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day was able to cure 50 to 60% of the surviving animals, independently of the infecting strain, while no cures were observed with benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day. The levels of cure observed in this chronic model were lower than those obtained in a previous study with the Bertoldo strain (33), a fact which could be explained by intrinsic differences between the strains and/or by the longer treatment (total of 43 doses) used in that study.

FIG. 3.

Effects of SCH 56592 and benznidazole treatment on survival of immunocompetent hosts in a murine model of chronic Chagas' disease. Normal female albino Swiss mice were each challenged with 30 blood trypomastigotes of the CL (A), Y (B), or Colombiana (C) strain, and oral treatment was initiated 120 days p.i. for a total of 20 daily consecutive doses. Each experimental group contained 12 animals. Symbols: ■, control (untreated) animals; ▴, animals which received SCH 56592 at 20 mg/kg/day; ●, animals which received benznidazole at 100 mg/kg/day. Statistical analyses of the survival plots were carried out with both the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) and Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon tests. For details, see the text.

TABLE 4.

Effects of SCH 56592 and benznidazole in a murine model of chronic Chagas' disease with different strains of T. cruzi

| Strain | No. of negative mice/no. tested

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (untreated) | Benznidazole, 100 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 5 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 10 mg/kg/day | SCH 56592, 20 mg/kg/day | |

| CL | 0/12 | 0/5 | 3/8 | 4/6 | 4/7 |

| Y | 0/12 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 3/6 | 4/8 |

| Colombiana | 0/12 | 0/4 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 3/6 |

Female albino Swiss mice (18 to 20 g) were inoculated with 30 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the indicated strain, and treatment was started 120 days p.i. The drugs were given orally for 20 days. Parasitological cure of animals which survived until the end of the observation period (191 days p.i.) was assessed by hemoculture, xenodiagnosis, and flow cytometry analysis for anti-live T. cruzi antibodies. Animals were considered cured when all three tests were negative (for details see Materials and Methods).

A recent report demonstrated the possibility of inducing azole resistance in T. cruzi by exposing mammalian stages of the parasite to increasing concentrations of fluconazole in vitro (5). Cross-resistance was demonstrated with other azoles, such as ketoconazole, both in vitro and in vivo. However, there was a significant reduction in the virulence of the azole-resistant parasites, a fact that could indicate a possible relationship between the mechanism of drug resistance and loss of viability of the parasite in its mammalian host (5). In the present work we found that naturally ketoconazole-resistant strains are highly susceptible to the triazole derivative SCH 56592. Our results agree with those obtained by Oakley et al. (21) and Lozano-Chiu et al. (14), who demonstrated that SCH 56592 was active, both in vitro and in vivo, against Aspergillus and Fusarium populations completely resistant to the currently available azoles (fluconazole and itraconazole). It has been argued before (33) that the superior intrinsic antifungal and antiprotozoal activity of SCH 56592 could probably be associated with the higher affinity of this triazole derivative to its biochemical target, cytochrome P-450-dependent C14 sterol demethylase (Sanglard et al., 37th ICAAC).

In conclusion, our results indicated that SCH 56592 has trypanocidal activity against a variety of T. cruzi strains, including benznidazole-, nifurtimox-, and ketoconazole-resistant organisms, in murine models of both acute and chronic Chagas' disease and that this activity is retained to a large extent even if the host is immunosuppressed. Such results have been obtained before only with the bis-triazole D0870 (J. Molina, M. S. S. Araujo, M. E. S. Pereira, Z. Brener, and J. A. Urbina, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. B-41b, 1997; Molina et al., unpublished data) but are consistent with recent reports on the efficacy of SCH 56592 in the treatment and prevention of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in persistently neutropenic rabbits (Petraitiene et al., 39th ICAAC) as well as in the treatment of azole-refractory candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with advanced AIDS (Skiest et al., 39th ICAAC). Taken together, these results support the proposal that SCH 56592 be considered for clinical trials in human Chagas' disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work received financial support from Programa de Apoio a Nucleos de Excelencia do MCT (PRONEX # 2704), Brazil, and the UNDP/World Bank/World Health Organization Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (grant 970297).

REFERENCES

- 1.Araújo M S S, Molina J, Pereira M E S, Brener Z. Combination of drugs in the treatment of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1996;91(Suppl. 1):315. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761996000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brener Z. Trypanosoma cruzi: taxonomy, morphology and life cycle. In: Wendel S, Brener Z, Camargo M E, Rassi A, editors. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis): its impact on tranfusion and clinical medicine. São Paulo, Brazil: ISBT Brazil'92; 1992. pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brener Z, Cançado J R, Galvão L M, da Luz Z M P, Filardi L D S, Pereira M E S, Santos L M T, Cançado C B. An experimental and clinical assay with ketoconazole in the treatment of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1993;88:149–153. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761993000100023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brener Z, Gazzinelli R T. Immunological control of Trypanosoma cruzi infection and pathogenesis of Chagas' disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;114:103–110. doi: 10.1159/000237653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckner F S, Wilson A J, White T C, Van Voorhis W C. Induction of resistance to azole drugs in Trypanosoma cruzi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3245–3250. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly P, Wheat J, Schnizlein-Nick C, Durkin M, Kohler S, Smedema M, Goldberg J, Brizendine E, Loebenberg D. Comparison of a new triazole antifungal agent, Schering 56592, with itraconazole and amphotericin B for treatment of histoplasmosis in immunocompetent mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:322–328. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croft S L, Urbina J A, Brun R. Chemotherapy of human leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis. In: Hide G, Mottram J C, Coombs G H, Holmes P H, editors. Trypanomiasis and leishmaniasis. London, England: CAB International; 1997. pp. 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Castro S L. The challenge of Chagas disease chemotherapy: an update of drugs assayed against Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 1993;53:83–98. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira M S, Nishioka S A, Rocha A, Silva A M. Doença de Chagas e imunosupressão. In: Pinto Dias J C, Rodrigues Coura J, editors. Clínica y terapêutica de doença de Chagas. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Editora Fiocruz; 1997. pp. 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filardi L S, Brener Z. Susceptibility and natural resistance of Trypanosoma cruzi strains to drugs used in Chagas disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:755–759. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson L, Grover F, Gutteridge W E, Klein R A, Peters W, Neal R A, Miles M A, Scott M T, Nourish R, Ager B P. Suggested guidelines for work with live Trypanosoma cruzi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:416–419. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law D, Moore C B, Denning D W. Activity of SCH 56592 compared with those of fluconazole and itraconazole against Candida spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2310–2311. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liendo A, Lazardi K, Urbina J A. Antiproliferative effects and mechanism of action of D0870 and its S(−) enantiomer against Trypanosoma cruzi. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:197–205. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozano-Chiu M, Rikan S, Paetznick V L, Anaissie E J, Loebenberg D, Rex J H. Treatment of murine fusariosis with SCH 56592. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:589–591. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutz J E, Clemons K V, Aristizabal B H, Stevens D A. Activity of the triazole SCH 56592 against disseminated murine coccidiodomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1558–1561. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado R A, Molina J, Payares G, Urbina J A. Experimental chemotherapy with combinations of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors in murine models of Chagas disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1353–1359. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins-Filho O, Pereira M E S, Carvalho J S, Cançado J R, Brener Z. Flow cytometry, a new approach to detect anti-live trypomastigote antibodies and monitor the efficacy of specific treatment in human Chagas' disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:569–573. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.5.569-573.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCabe R E. Failure of ketoconazole to cure chronic murine Chagas disease. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1408–1409. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.6.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michailowsky V, Murta S M F, Carvalho-Oliveira L, Pereira M E S, Ferreira L R P, Brener Z, Romanha A J, Gazzinelli R T. Interleukin-12 enhances in vivo parasiticidal effect of benznidazole during acute experimental infection with a naturally drug-resistant strain of Trypanosoma cruzi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2549–2556. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreira A A B, DeSouza H B W T, Amato Neto V, Matsubara L, Pinto P L S, Tolezano J E, Nunes E V, Okumura M. Avaliacão da atividade terapêutica do itraconazol nas infecçoes crônicas, experimental e humana, pelo Trypanosoma cruzi. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1992;34:177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oakley K L, Morrisey G, Denning D W. Efficacy of SCH 56592 in a temporarily neutropenic murine model of invasive aspergillosis with an itraconazole-susceptible and itraconazole-resistant isolate of Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1504–1507. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perfect J R, Cox G M, Dodge R K, Schell W A. In vitro and in vivo efficacies of the azole SCH56592 against Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1910–1913. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Jones R N. Activity of a new triazole, SCH 56592, compared with those of four other antifungal agents tested against clinical isolates of Candida spp. and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:233–235. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quintas L E M, de Castro S L, Urbina J A, Borba-Santos J A, Pinto C N, Siqueira-Batista R, Miranda Filho N. Tratamento da doença de Chagas. In: Siqueira-Batista R, Corrêa A D, Higgins D W, editors. Molestia de Chagas. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Editora Cultura Medica; 1996. pp. 125–170. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quintas L E M, Siqueira-Batista R. Inmunologia. In: Siqueira-Batista R, Corrêa A D, Huggins D W, editors. Molestia de Chagas. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Editora Cultura Medica; 1996. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rassi A, Luquetti A O. Therapy of Chagas disease. In: Wendel S, Brener Z, Camargo M E, Rassi A, editors. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis): its impact on transfusion and clinical medicine. São Paulo, Brazil: ISBT Brazil'92; 1992. pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocha A, Menezes A C O, Silva A M, Ferreira M S, Nishioka S A, Burgarelli M K N, Almeida E, Turcato G, Jr, Metze K, Lopes E R. Pathology of patients with Chagas' disease and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:261–268. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugar A M, Liu X-P. In vitro and in vivo activities of SCH 56592 against Blastomyces dermatitidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1314–1316. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urbina J A. Lipid biosynthesis pathways as chemotherapeutic targets in kinetoplastid parasites. Parasitology. 1997;117:S91–S99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urbina J A. Chemotherapy of Chagas' disease: the how and the why. J Mol Med. 1999;77:332–338. doi: 10.1007/s001090050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urbina J A, Lazardi K, Aguirre T, Piras M M, Piras R. Antiproliferative synergism of the allylamine SF-86327 and ketoconazole on epimastigotes and amastigotes of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1237–1242. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.8.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urbina J A, Lazardi K, Marchan E, Visbal G, Aguirre T, Piras M M, Piras R, Maldonado R A, Payares G, De Souza W. Mevinolin (lovastatin) potentiates the antiproliferative effects of ketoconazole and terbinafine against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vivo and in vitro studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:580–591. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urbina J A, Payares G, Contreras L M, Liendo A, Sanoja C, Molina J, Piras M, Piras R, Perez N, Wincker P, Loebenberg D. Antiproliferative effects and mechanism of action of SCH 56592 against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vitro and in vivo studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1771–1777. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urbina J A, Payares G, Molina J, Sanoja C, Liendo A, Lazardi K, Piras M M, Piras R, Perez N, Wincker P, Ryley J F. Cure of short- and long-term experimental Chagas disease using D0870. Science. 1996;273:969–971. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbina J A, Vivas J, Lazardi K, Molina J, Payares G, Piras M M, Piras R. Antiproliferative effects of Δ24(25) sterol methyl transferase inhibitors on Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vitro and in vivo studies. Chemotherapy. 1996;42:294–307. doi: 10.1159/000239458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbina J A, Vivas J, Visbal G, Contreras L M. Modification of the sterol composition of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi epimastigotes by Δ24(25)-sterol methyl transferase inhibitors and their combinations with ketoconazole. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;73:199–210. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00117-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]