Abstract

Graphene-based nanomaterials (GBNMs) has been thoroughly investigated and extensively used in many biomedical fields, especially cancer therapy and bacteria-induced infectious diseases treatment, which have attracted more and more attentions due to the improved therapeutic efficacy and reduced reverse effect. GBNMs, as classic two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials, have unique structure and excellent physicochemical properties, exhibiting tremendous potential in cancer therapy and bacteria-induced infectious diseases treatment. In this review, we first introduced the recent advances in development of GBNMs and GBNMs-based treatment strategies for cancer, including photothermal therapy (PTT), photodynamic therapy (PDT) and multiple combination therapies. Then, we surveyed the research progress of applications of GBNMs in anti-infection such as antimicrobial resistance, wound healing and removal of biofilm. The mechanism of GBNMs was also expounded. Finally, we concluded and discussed the advantages, challenges/limitations and perspective about the development of GBNMs and GBNMs-based therapies. Collectively, we think that GBNMs could be potential in clinic to promote the improvement of cancer therapy and infections treatment.

Keywords: Graphene, Phototherapy, Cancer therapy, Anti-infection, 2D materials

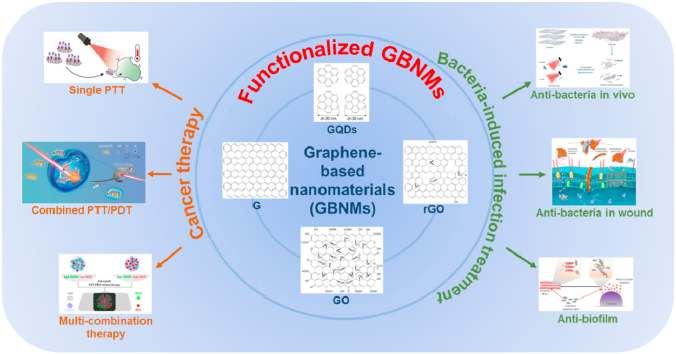

Graphical abstract

Graphene-based nanomaterials (GBNMs) has been thoroughly investigated and extensively used in cancer therapy and anti-infections with improved therapeutic efficacy and reduced reverse effect due to the unique structure and excellent properties.

Highlights

-

•

Development of GBNMs with unique structure and excellent properties.

-

•

GBNMs-based therapies for anticancer with improved therapeutic efficacy.

-

•

GBNMs with antimicrobial activity are widely used in anti-infections.

-

•

The challenges and perspective of GBNMs for clinical use were thoroughly discussed.

1. Introduction

Graphene has unique two-dimensional structure and excellent physicochemical properties, which is the most promising nanomaterial in 21st century [1,2]. Graphene and its derivatives like graphene quantum dots (GQDs), graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) (so-called graphene-based nanomaterials, GBNMs) have been widely applied in biomedical fields due to the superior properties [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. For example, GQDs exhibit excellent photoluminescence property [16], high photostability [17], and good biocompatibility [18]. GO and rGO possess large surface area, sharp edges, and great photothermal conversion effect [19,20]. These unique properties play an important role for the application of GBNMs in many biomedical fields.

It's of great significance to develop efficient therapeutics and effective treatments for cancer which is one of the highest mortality diseases in the world [[21], [22], [23], [24]]. Although chemotherapy is one of the most common cancer treatments in clinic, there are some intrinsic drawbacks, such as severe side-effects, low therapeutic efficacy, multi-drug resistance, off-targeting and so on [25,26]. Radiotherapy is another conventional cancer treatment, which depends on huge laser energy to destroy tumor cells. However, the oxygen-deficient microenvironment within tumor cells limits cells' sensitivity to X-ray laser, resulting in poor therapeutic efficacy [27,28]. Meanwhile, bacteria-induced infection is one of the greatest threats to public health, causing difficult recovery and high mortality diseases [29,30]. In the past decades, antibiotics are the major therapeutic strategy for infectious diseases treatment. However, antibiotics are meeting huge challenge with drug-resistant bacteria strains (superbugs) due to the overuse and misuse of antibiotics [[31], [32], [33], [34]]. In recent years, phototherapy has attracted wide attention due to its excellent therapeutic efficacy for cancer and infectious diseases, reduced side-effects and negligible damage to normal tissues [[35], [36], [37]]. Moreover, phototherapy does not induce the drug resistance from bacteria in anti-infection treatment [38,39]. Photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) are the two major parts of phototherapy. PTT is depending on photothermal agent that can adsorb laser energy and transfer to heat under laser irradiation, resulting in local hyperthermal which can cause the death of tumor cells or bacteria. For PTT, photothermal conversion efficiency is the most important factor [[40], [41], [42], [43]]. PDT is relying on generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) to inhibit the growth of tumor cells or kill bacteria under laser irradiation, indicating the photosensitizer (PS) is the key factor for PDT [[44], [45], [46], [47]]. As reported, GBNMs exhibit great photothermal effect under near infrared ray (NIR) irradiation, indicating the potential as photothermal agent in PTT [20,[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53]]. What's more, GBNMs can produce ROS under laser irradiation, inducing oxidative stress to tumor cells or bacterial cells to kill them [[54], [55], [56]]. Summarily, phototherapy based on GBNMs exhibits excellent performance in cancer therapy and infectious diseases treatment, providing a promising therapeutic approach in clinic. Some studies reported that bacteria-induced infections were related to cancer, particularly increasing the risk of cancer [57]. Cancer patients have defective immune response system due to the side-effects induced by chemotherapy and other treatments. Furthermore, it has been proved that bacteria-induced infections with inflammation could cause DNA damage of host cells, which increase the risk of cancer [58,59].

Herein, it is worth summarizing the recent research updates on GBNMs-based therapies for cancer and bacteria-induced infectious diseases (Scheme 1 and Table 1). In this review, we firstly sum up the recent studies on GBNMs-based treatment strategies for cancer from three aspects: single therapy, combination therapy and multi-therapy. Then, considering the bacteria-induced infectious disease treatment, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), wound healing and infection management based on GBNMs were introduced and discussed. Furthermore, some current challenges/limitations and future perspectives of GBNMs used in cancer therapy and bacteria-induced infectious disease treatment are included here. In summary, we think that GBNMs might be a promising candidate in many biomedical applications.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of GBNMs-based therapies for cancer and bacteria-induced infectious diseases. Figures for GBNMs: Reproduced with permission [60]. Figure for single PTT: Reproduced with permission [50]. Figure for combined PTT/PDT: Reproduced with permission [61]. Figure for multi-combination therapy: Reproduced with permission [62]. Figure for anti-bacteria in vivo: Reproduced with permission [63]. Figure for anti-bacteria in wound: Reproduced with permission [64]. Figure for anti-biofilm: Reproduced with permission [65].

Table 1.

The information of GBNMs-based therapies for cancer and bacteria-induced infectious diseases treatments.

| GBNMs | Properties | Treatment | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bare GBNMs | ||||

| G | Sharp edges | Membrane disruption | Anti-bacterial | [112,133] |

| GQDs | PTA | PTT | Anti-cancer | [51,67] |

| PS | PDT | Anti-cancer | [[54], [55], [56]] | |

| Interfering molecule | PTT/Anti-biofilm | Anti-bacterial | [65] | |

| GO | Sharp edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/trap/oxidative stress | Anti-bacterial | [106,107,109] |

| rGO | Sharp edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/oxidative stress | Anti-bacterial | [107,108] |

| Modified GBNMs | ||||

| GO-PEG | PTA | PTT | Anti-cancer | [48] |

| rGO-HA | PTA | PTT | Anti-cancer | [50] |

| mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox | PTA/drug carrier | PTT/chemotherapy | Anti-cancer | [78] |

| BiP5W30/rGO/PVP | PTA/RSs carrier | PTT/radiotherapy | Anti-cancer | [84] |

| PAH/FA/PEG/GO/siRNA | PTA/gene carrier | PTT/gene therapy | Anti-cancer | [92] |

| GO-(HPPH)-PEG-HK | PS/carrier | PDT/immunotherapy | Anti-cancer | [99] |

| rGO/MTX/SB | PTA/drug carrier | PTT/chemotherapy/immunotherapy | Anti-cancer | [15] |

| GP/AgNW/doped/GP/IrOx | Transparent bioelectronics | PTT/PDT/detecting/chemotherapy | Anti-cancer | [102] |

| N-GQD/HMSN/C3N4/PEG-RGD | PTA | PTT/PDT/imaging | Anti-cancer | [100] |

| GO/Ti substrate | Shape edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/oxidative stress | Anti-bacterial | [126] |

| GO/Zn/Ni/Sn/steel substrate | ROS | Oxidative stress/Electron transfer | Anti-bacterial | [125] |

| GO/NCD/Hap/Ti | Electron donors or receptors/carrier | PTT/PDT/electron transfer | Anti-bacterial | [127] |

| GO/Ag | Sharp edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/oxidative stress/Ag2+ | Anti-bacterial | [110] |

| GO/ZnO | Sharp edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/oxidative stress | Anti-bacterial | [113] |

| GO-PVK | Large surface | Wrap | Anti-bacterial | [114] |

| rGO/Ag | PTA/ROS | Hyperthermia/oxidative stress/Ag2+ | Anti-bacterial | [123] |

| rGO-Gu2O | Carrier/sharp edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/Cu+/oxidative stress | Anti-bacterial | [122] |

| rGO-NPF/rGO-NBF | Sharp edges/ROS | Membrane disruption/oxidative stress | Anti-bacterial | [115] |

| Ag/Gu/G | Carrier | Ag2+/Cu2+ | Anti-bacterial | [124] |

| TRB-ZnO/G | PTA/carrier/sharp edges | Membrane disruption/Zn2+/hyperthermia | Anti-bacterial | [64] |

2. Application of GBNMs in cancer therapy

2.1. GBNMs-based PTT

Graphene-based nanomaterials mainly include graphene (G), graphene quantum dots (GQDs), graphene oxide (GO), and reduced graphene oxide (rGO). GQDs exhibit intrinsic photoluminescent property which is used for imaging and tracking for cancer therapy [66]. GQDs can be rapidly cleared from the body due to the small particle size. In addition, GQDs exhibit high photothermal conversion ability reported by Thakur and co-workers [51]. They synthesized GQDs using withered leaves as raw materials, which was an environment friendly and low-cost method. In this work, GQDs exhibited great biocompatibility and concentration-dependent photothermal conversion ability under NIR laser irradiation. MDA-MB-231 breast cells treated with different concentrations of GQDs solutions with NIR laser irradiation expressed different cell viability, and the highest concentration corresponded to the lowest survival rate. The results indicated that GQDs was a promising candidate for PTT. Liu et al. synthesized GQDs-based nanoparticles which could respond to NIR-II (1000–1700 nm) irradiation, showing enhanced inhibition of tumor growth compared with controls (Fig. 1a) [67]. As reported, considering the penetration activity, the second NIR window (1000–1700 nm, NIR-II) showed about 1.5 times penetration depth compared with first NIR window (700–950 nm, NIR-I) in body, indicating the improved therapeutic efficacy of phototherapy based on the prepared GQD nanoparticles [68]. Fig. 1b was the synthesis method of GQDs-based nanoparticles (so-called 9T-GQDs). The photothermal conversion ability of 9T-GQDs under NIR-II irradiation was further confirmed, as shown in Fig. 1c. The higher concentration of 9T-GQDs, the more temperature changes in the experiment results. There were negligible temperature changes in the control group (pure water with NIR-II irradiation). These results demonstrated that the photothermal conversion ability of 9T-GQDs was increased with the concentration increasing. The authors next studied the in vitro cytotoxicity of 9T-GQDs with or without NIR-II irradiation against 4T1 cells. As shown in Fig. 1d, even at the highest concentration of 9T-GQDs (100 mg/L) without NIR-II irradiation, the cell viability was still higher than 90%, showing the negligible cytotoxicity of 9T-GQDs. By contrast, under NIR-II irradiation, the cell viability of 4T1 cells was significantly decreased with increase of 9T-GQDs concentration. The confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images demonstrated that 4T1 cells could be killed effectively while treated with high concentration 9T-GQDs with NIR-II light (Fig. 1e–h). They further evaluated the therapeutic efficacy in vivo (Fig. 1i-m). 9T-GQDs exhibited excellent fluorescence ability under NIR light, which could locate tumor position in mice after intravenous injection with 9T-GQDs (Fig. 1i–j). As shown in Fig. 1k, the relative tumor volume of mice treated with 9T-GQDs with NIR-II irradiation was much lower compared to those of controls (PBS, PBS with NIR-II and free 9T-GQDs treatments), showing the much higher therapeutic efficacy. The images and volume of tumor of mice with different treatments at Day 14 were shown in Fig. 1m, further evidencing the higher therapeutic efficacy of 9T-GQDs with NIR-II irradiation. Furthermore, the body weight of mice treated with different formulations did not show significant difference, and slowly increased during the whole experiment (Fig. 1l), indicating the low side-effect. The PTT mechanism of 9T-GQDs was based on the larger conjugated system including π bonding molecular orbital and π* antibonding molecule orbital. The π electrons in π bonding molecular orbital absorb the energy of laser under the irradiation and transition to π* antibonding molecule orbital. In the process of the excited electrons returning to the ground state, part of the energy is released in the form of heat, resulting in a photothermal effect [69,70]. Hyperthermia in the tumor could induce the death of tumor cells. Taken together, 9T-GQDs-based PTT exhibited higher cancer therapeutic efficacy under NIR-II laser irradiation. In this work, GQDs exhibited higher photothermal conversion efficiency, higher therapeutic efficacy and low toxicity, which could be a promising PTA in PTT field.

Fig. 1.

a. The schematic illustration of 9T-GQDs-based imaging guide PTT under NIR-II laser irradiation. b. The schematic of synthesis of 9T-GQDs. c. Temperature change of pure water and 9T-GQDs at different concentrations under NIR-II irradiation for 5 min. d. Cell viability of 4T1 cells treated with 9T-GQDs at different concentrations with or without NIR-II irradiation. e-h. CLSM images of 4T1 cells treated with 9T-GQDs at different concentrations (e, 0 μg/mL; f, 25 μg/mL; g, 50 μg/mL; h, 100 μg/mL) under NIR-II irradiation for 5 min. The samples were stained with caltein AM (green for live cells) and propidium iodide (red for dead cells). Scale bar: 50 μm. i. NIR images of PBS and 9T-GQDs under 710 nm laser irradiation. j. Bright (left) and NIR images (right) of tumor-bearing mice treated with 9T-GQDs for 2 days. The relative tumor volume (k) and body weight (l) curves of tumor-bearing mice treated with different formulations within 14 days. m. The tumor volume and optical pictures (inset) of tumor-bearing mice on Day 14. Student's two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis (n = 4, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Cited and reproduced from Ref. [67].

Similarly, many studies reported the photothermal conversion effect of graphene [49], graphene oxide [48], and reduced graphene oxide [50], which are potential candidates for PTT in cancer therapy. Although they have nanosheet structure and large surface area, these materials are easy to aggregate in the solution which limits their application in PTT. The effective method to overcome this barrier is functionalization on the surface using functional materials such as polymer (e.g. polyethylene glycol, PEG) to enhance the dispersibility and biocompatibility. Therefore, graphene, graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide need proper functionalization before use in PTT. For instance, Yang et al. prepared a nanographene sheet (NGS) modified with hydrophilic PEG segment as protect shell and Cy7 as label for imaging and tracking [48]. The hydrophilic PEG shell was able to enhance the biocompatibility of NGS system, and Cy7 was used to label the behaviors of NGS-PEG in body. In this work, NGS-PEG nanosystem absorbed the light energy and transfer to heat in the tumor cell under the NIR light irradiation, followed by generating the local hyperthermal to kill the tumor cells effectively, which was attributed to the great photothermal conversion efficiency of NGS. In addition, Lima-Sousa et al. reported an efficient photothermal material based on rGO modified with hyaluronic acid (HA) which was not only an amphiphilic material to enhance the biocompatibility but also a target ligand for specific delivery of drug [50]. PTT mediated by this prepared rGO-based system showed much higher therapeutic efficacy compared with the controls.

2.2. GBNMs-based combination therapy

Single therapy, as the common strategy for cancer therapy in the past decades, is limited by the unsatisfied treatment outcome. In recent years, combination therapy is attracting huge attentions due to the synergic effect, which is promising treatment strategy.

2.2.1. GBNMs-based PTT/chemotherapy combination therapy

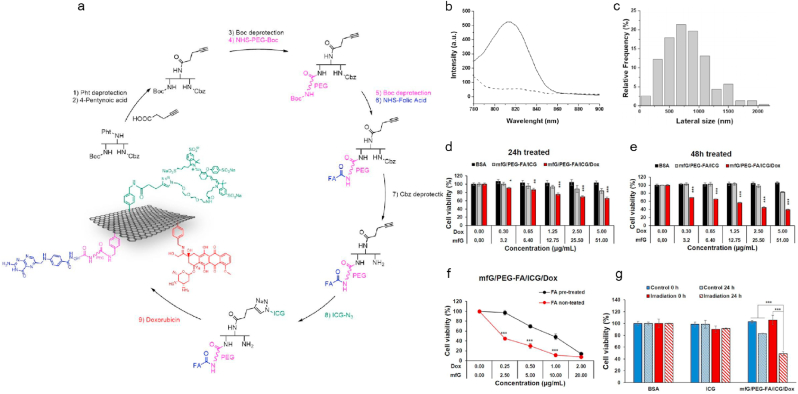

It is of great significance to develop effective strategy to overcome the multi-drug resistance of chemotherapy in clinic. PTT can improve the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapy through the promotion of drug release at tumor site via hyperthermia, followed by enhancing the cellular uptake of drug through the increased cell membrane permeability [[71], [72], [73], [74], [75]]. Therefore, the combination therapy based on chemotherapy and PTT exhibits higher therapeutic efficacy than chemotherapy or PTT alone. GBNMs have large surface area and can be easily functionalized, which can be used as drug carriers for chemotherapy. In addition, GBNMs exhibits excellent adsorption ability in NIR region and photo-thermal transformation efficiency under NIR irradiation. With these properties, GBNMs could become great PTA for PTT. Wang et al. prepared a novel GO-PEG/LA-CUR nano-hybrid system for targeted treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The results indicated GO-PEG/LA-CUR could specifically target to the tumor cells, enhance the cellular uptake of drugs and effectively inhibit the tumor growth through the synergistic effect of chemotherapy and PTT under NIR light [76]. Qi et al. synthesized Dox@rGO-COOH/Au nanocomposites which exhibited great photothermal effect and significantly promoted the drug release under NIR irradiation [77]. Lucherelli et al. designed and prepared a mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposite based on multifunctional graphene (mfG), which exhibited superior synergetic therapeutic efficiency through combination of PTT and chemotherapy [78]. The synthesis method of nanocomposites was showed in Fig. 2a. MfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites showed obvious fluorescence at 815 nm laser (Fig. 2b). The lateral size of mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites was about 700 nm (Fig. 2c) [[79], [80], [81]]. The authors next measured the anti-tumor ability of mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites in vitro, and the cell viability of HeLa cells was decreased to about 40% after treated with mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites for 48 h (Fig. 2d–e). As reported, the tumor cells overexpressed the folic acid (FA) receptors compared with normal cells [82], FA functionalized mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites could specifically target to the tumor cells, as shown in Fig. 2f. The authors next studied the viability of HeLa cells treated with mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites and controls (BSA and ICG) with or without NIR irradiation for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 2g, the viability of HeLa cells was decreased to approximately 50% after treatment with mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox nanocomposites under NIR irradiation for 24 h, which was much lower than those of controls. Here, mfG was used as a template for fabrication of multi-functional drug delivery system, followed by being modified with PEG-FA as tumor-targeted ligand and loaded with Dox for chemotherapy. When the nanotherapeutics targeted to the tumor cells, hyperthermal caused by GBNMs under NIR irradiation could damage the tumor cells and accelerate the release and uptake of Dox by tumor cells, resulting in synergetic therapeutic effect through combined PTT and chemotherapy. This work provided a promising strategy to overcome the drawbacks of chemotherapy and opened a new door in clinic cancer therapy.

Fig. 2.

a. Schematic illustration of synthesis of the mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox. b. Fluorescence spectrum of mfG/PEG-FA/ICG (black curve) and control mfG/PEG-FA (dashed curve). λex: 750 nm, λem: 780–900 nm. c. Histogram of lateral size distribution of the mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox. d-e. Cell viability of HeLa cells treated with BSA, mfG/PEG-FA/ICG and mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox for 24 h (d) and 48 h (e), respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4). f. Cell viability of HeLa cells treated with mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox for 48 h with or without pre-treatment of free 10% of FA, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4), ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test comparisons with the equivalent concentration of FA pretreated counterpart). g. Cell viability of HeLa cells treated with BSA (20 μg/mL), ICG (0.9 μg/mL) and mfG/PEG-FA/ICG/Dox (20 μg/mL of mfG) with or without 785 nm laser irradiation for 10 min. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test to 0 μg/mL) (Student's t-test). Cited and reproduced from Ref. [78].

2.2.2. GBNMs-based PTT/RT combination therapy

Radiotherapy (RT) is one of traditional cancer therapy methods in clinic, which can kill local tumor cells without invasive treatment. However, therapeutic efficacy of RT is influenced by oxygen-deficient tumor microenvironment. The hypoxic cancer cells show less sensitivity to X-ray irradiation, seriously reducing the therapeutic efficacy. In recent years, some studies reported that hyperthermal induced by photothermal effect can dramatically improve intratumoral oxygen content through promoting blood flow, which can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of RT [83]. Therefore, the combination of RT and PTT is a promising cancer therapy strategy. Zhou et al. reported a powerful nanoplatform composed of BiP5W30, rGO and PVP (so-called PVP-PG) [84]. The synthesis process was showed in Fig. 3a. BiP5W30 could absorb more X-rays and deposited the energy in tumor cells to improve RT effect, and rGO could increase the oxygen concentration within tumor cells resulting from enhanced intratumoral blood flow induced by photothermal effect. Firstly, the authors explained the mechanism of radiocatalystic effect and redox-reaction effect based on PVP-PG for cancer combination therapy (Fig. 3b and d). With X-ray, the PVP-PG could product toxic hydroxyl radical through consumption hydrogen peroxide and increase the ROS content through decreasing glutathione [[85], [86], [87], [88]], followed by improving the anti-tumor effect of PVP-PG. Then, they qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed the ROS, as shown in Fig. 3c–e. Finally, they evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of PVP-PG via combination RT and PTT in vivo, as shown in Fig. 3f–g. The tumor weights of mice treated with PBS, PVP-PG, PVP-PG with NIR and PVP-PG with X-ray for 25-day were approximately 1.25 g, 1.05 g, 0.35 g and 0.24 g, respectively. By contrast, the tumor of mice treated with PVP-PG with NIR and X-ray for 25-day was almost disappeared (<0.05 g), indicating the highest therapeutic efficacy of combination therapy (PTT and RT) basing on PVP-PG.

Fig. 3.

a. Schematic illustration of preparation of PVP-PG. b. Schematic illustration of radiocatalystic effect of PVP-PG with X-ray. c. Fluorescence images of H2O2 in HeLa cells with different treatments. H2O2 was marked as red dots. (Scale bar: 50 μm). d. Schematic illustration of redox-reaction effect of PVP-PG. e. Relative GSH amount in tumor cells with different treatments. The tumor weights (f) and images (g) of tumor-bearing mice treated with different formulations after 25 days. P values: ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Black circle indicates the eliminated tumors. Cited and reproduced from Ref. [84].

2.2.3. GBNMs-based PTT/gene therapy combination therapy

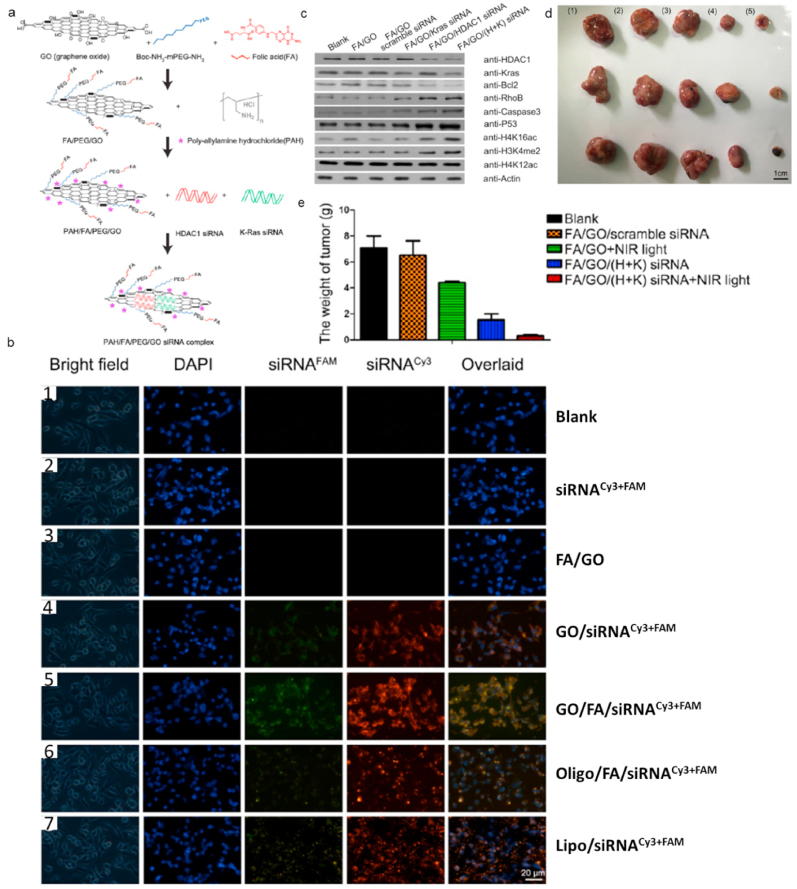

Gene therapy (GT), as an emerging cancer therapy, is a strategy for delivering gene to specific tumor cells to express proapoptotic proteins or reduce overexpressed oncogenic proteins to cure cancer. The main drawbacks of GT are the natural instability [89] and low uptake gene in tumor cells [90]. As aforementioned, hyperthermia induced by PTT has capability to enhance cellular uptake, which can be used to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of GT. Meanwhile, GT can also improve PTT efficiency via decreasing the tumor cells resistance against hyperthermal injury or inhibiting expression of heat shock protein. Therefore, combining GT and PTT based on GBNMs is a promising cancer therapeutic method. Kim et al. reported a photothermally controlled gene delivery carriers based on PEG-BPRI-rGO nanocomposites which could load plasmid DNA (pDNA), resulting in PEG-BPRI-rGO/pDNA nano-system that showed great gene transfection in vitro studies. With NIR irradiation, PEG-BPRI-rGO/pDNA showed much higher gene transfection effect due to faster endosomal escape of nanocomposites induced by photothermal effect of rGO [91]. Yin et al. also reported the excellent synergistic therapeutic efficacy for cancer treatment via the combination of GT and PTT [92]. They selected Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and K-Ras as therapeutic siRNA, and prepared nanocomposites GO/FA/PEG/PAH(FA/GO) as gene delivery system. FA/GO/(H+K) siRNA system was fabricated following the route (Fig. 4a). Fig. 4b showed the uptake level and distribution of HDAC1 and K-Ras siRNA inside tumor cells in vitro, indicating the strongest accumulation of siRNAs in tumor cells treated with FA/GO/(H+K) siRNA. They also proved that FA/GO/(H+K) siRNA could effectively inhibit the expression of HDAC1 and K-Ras gene inside the tumor cells which could induce the apoptosis of tumor cells [[93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98]]. The above results showed the great cancer therapeutic efficacy through GO-based GT. Inspired by these results, they evaluated the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of FA/GO/(H+K) siRNA under NIR irradiation. The tumor-bearing mice were injected with PBS or GO-based nano-formulations with or without NIR light. As shown in Fig. 4d and e, the FA/GO/(H+K) siRNAs with NIR light exhibited the highest therapeutic efficacy compared with other controls.

Fig. 4.

a. Schematic illustration of preparation of PAH/FA/PEG/GO siRNA complex. b. Fluorescent images of MIA PaCa-2 cells after receiving different treatments. (1) PBS (blank); (2) free K-Ras siRNACy3 + HDAC1 siRNAFAM (siRNACy3+FAM) and (3) FA/PEG/PAH/GO (FA/GO) (negative controls); (6) Oligofectamine-conjugated siRNA (Oligo/siRNACy3+FAM) and (7) Lipofectamine 2000 (Lipo/siRNACy3+FAM) (positive controls); and Kras-siRNACy3 and HDAC1-siRNAFAM co-delivery by GO/PEG/PAH (GO/siRNACy3+FAM) or GO/PEG/PAH/FA (GO/FA/siRNACy3+FAM). The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (pseudo-colored in blue), and signals from FAM and Cy3 were designated in green and red, respectively. Bright field images were merged with DAPI and siRNACy3+FAM (overlaid) to indicate the cell-penetrating abilities of different complexes. c. Relative protein levels in MIA PaCa-2 cells with different GO-based nano-formulations treatments. The results were measured with western blotting, and actin was used as the protein loading control. Data were presented as means ± s.e.m. of triplicate experiments. **P < 0.01 vs PBS (blank). Tumor images (d) and weight (e) of tumor-bearing mice treated with (1) PBS, (2) FA/GO/scramble siRNA, (3) FA/GO with NIR light, (4) FA/GO/(H+K) siRNA or (5) FA/GO/(H+K) siRNA with NIR light. Cited and reproduced from the reference [92].

2.2.4. GBNMs-based PDT/immunotherapy combination therapy

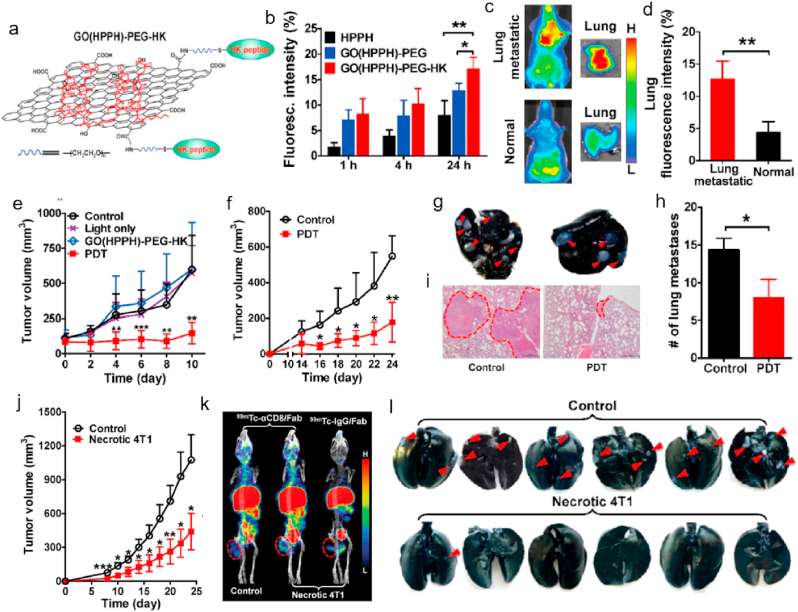

Immunotherapy is an emerging therapeutic strategy via activating the host immune response to kill the tumor cells. It is reported that PDT could accelerate the release of debris from tumor cells to stimulate the antitumor immunity, which can activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes to go inside the cancer cells, followed by inducing the destruct of residual cancer cells to prevent metastasis. Therefore, combination therapy based on PDT and immunotherapy might be a promising efficient treatment for cancer therapy. Yu et al. prepared a nanocomposite composed of GO, HPPH (photosensitizer), HK peptide (targeting ligand) and PEG (hydrophilic shell) (so-called GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK, Fig. 5a) for PDT-immunotherapy combination therapy [99]. They firstly studied the specific targeting ability of GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK for 4T1 tumor and metastatic 4T1 cells in pulmonary in vivo. The fluorescence intensity and accumulation of nanocomposite in 4T1 tumor and metastatic tumor in pulmonary was much higher compared with those of controls, as shown in Fig. 5b–d. The accumulated amount of nanocomposite was increased with the time increase. These results demonstrated that GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK nanocomposite could specifically target to the tumor cells after intravenous administration. Then, they evaluated the therapeutic efficiency of GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK for 4T1-bearing mice, and the tumor volume was obviously inhibited in comparison to the controls (Fig. 5e). The authors next investigated whether the PDT based on nanocomposite could activate the antitumor immunity for the second tumor. After 10 days of first treatment, the 4T1 tumor was further xenografted into the mice. And the indicated PDT was administrated for the mice. The tumor volume was significantly reduced compared with controls (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, the lung metastases tumor cells were also inhibited through the host immunity (Fig. g–i). Inspired by above results, they prepared the prophylactic vaccination with necrotic 4T1 cells using PDT based on GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK. The authors collected the necrotic 4T1 tumor cells through flow cytometry from the 4T1-bearing mice after PDT treatment. The healthy mice were vaccinated with necrotic 4T1 tumor cells. 7-day later, the tumor cells were inoculated into the mice to investigate the immunological memory of mice. The tumor volume of mice with and without prophylactic vaccination was recorded (Fig. 5j). They further confirmed that the antitumor immunity induced by necrotic 4T1 tumor cell vaccination was depended CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5k). Moreover, the prophylactic vaccination also showed high inhibition effect of lung metastasis in vivo compared with controls, as shown in Fig. 5l. The results demonstrated combination PDT-immunotherapy based on GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK was an effective synergistic therapeutic strategy for cancer therapy. Here, GO acted as a delivery system, FEG-HK was used as tumor-targeted ligand and HPPH was a photosensitizer for PDT. After deposition of GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK at tumor site, photosensitizer HPPH produced abundant ROS to cause oxidative stress to tumor cells, followed by inducing the apoptosis of tumor cells under NIR irradiation. Therefore, GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK could improve the solubility and target activity of conventional photosensitizer, causing effectively damage to tumor cells with improved therapeutic efficacy.

Fig. 5.

a. Preparation of GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK nanocomposite. b. The in vitro cellular uptake of different formulations by 4T1 tumors after incubation for different time. In vivo accumulation (c) and quantitative analysis (d) of GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK in lung in 4T1 tumor-bearing and normal BALB/c mice at 24 h post-injection. e. Tumors volume of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after different treatments (PBS, light only, GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK) without light and GO(HPPH)-PEG-HK) with light) recorded every 2 days. f. Tumor volume of the second 4T1 tumor in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after indicated treatments. Images (g) of India ink-filled lungs, histogram of metastatic lesions in the lung (h), and H&E staining of the lung tissue section (i). j. Tumor volume of subcutaneous 4T1 tumors in mice with (control) and without prophylactic vaccination using necrotic 4T1 cells. k. SPECT/CT imaging of 99mTc-αCD8/Fab and 99mTc-IgG/Fab in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice with (control) and without prophylactic vaccination using necrotic 4T1 cells. Tumors are marked by dashed circles. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. l. Quantitative analysis of tumor metastasis lesions in lungs of mice with (control) and without prophylactic vaccination using necrotic 4T1 cells. Cited and reproduced from the reference [99].

2.3. GBNMs-based multi-combination therapy

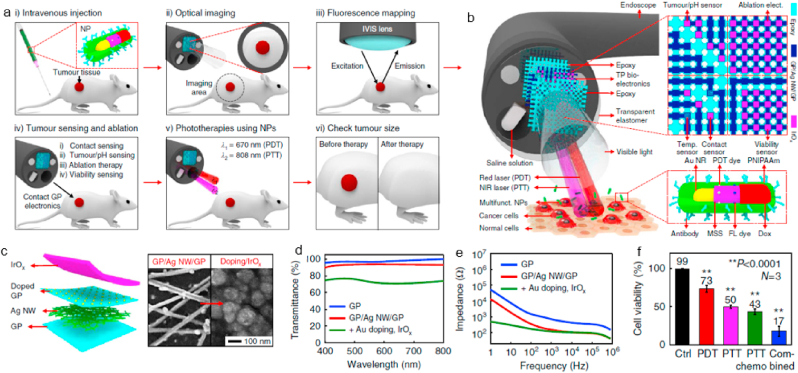

Recently, GBNMs-based multi-combination therapy is studied to further improve the therapeutic outcome [100]. Wo et al. fabricated a liposome-coated HMNS/SiO2/GQDs-Dox nanocomposite for multi-combination therapy including magneto mechanical therapy, PTT, PDT, and chemotherapy, which showed a superior antitumor effect with laser irradiation and a magnetic field [101]. GBNMs, as a candidate for PTA and PDA, exhibit excellent therapeutic effect in PTT and PDT. In addition, GBNMs show great electronics properties to apply in detection aspect. Lee et al. reported a smart endoscope system integrated diagnosis and therapy together [102]. The whole tumor treatment procedures were showed in Fig. 6a, and the structure of endoscope was showed in Fig. 6b. In this work, transparent bioelectronics based on the graphene hybrid was used for tumor diagnosis (Fig. 6c). Graphene hybrid exhibited good transparency, great stability and low contact impedance in the interface between tumor and endoscope, which play an important role in diagnosis (Fig. 6d–e). To investigate the diagnostic efficacy of graphene hybrid based transparent bioelectronics, resected HT-29 tissues and healthy tissues were used. The endoscope could recognize HT-29 tissues exactly through the difference contact impedance and pH level, then ablate the tissues to cure cancer, demonstrated effective diagnostic ability. In addition, they integrated therapeutic nanoparticles into this endoscope, which promoted the inhibition of tumor obviously via PTT, PDT, and chemotherapy simultaneously (Fig. 6f). In this work, the combination of diagnosis and multi-combination therapy exhibited great synergistic effects, enhancing the tumor recognition accuracy and therapeutic efficacy for cancer.

Fig. 6.

a. Schematic illustrations of multimodal cancer therapy procedures. b. Schematic illustrations of the multifunctional endoscope system through transparent bioelectronic devices and therapeutic nanoparticles. c. Structure and preparation (left) of graphene hybrid and SEM images (right) of graphene hybrid before and after the lrOx electrodeposition. d. Optical transmittance measurement of the graphene hybrid. e. Contact impedance of graphene hybrid in the interface between endoscope and tumor. f. Cell viability after different treatments. (**P < 0.0001, Student's t-test). Cited and reproduced from the reference [102].

3. Application of GBNMs in infectious diseases treatment

Microbial infection is a serious threat to human health in the world. The multi-functional nanomaterials-based therapeutics with antimicrobial activity play an important role in the fight with bacteria. GBNMs are attracting more and more attentions in the treatment and management of bacteria-induced infectious diseases due to their unique structure and excellent physicochemical properties [[103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110]]. Some studies have reported that GBNMs exhibited great antimicrobial activity [[111], [112], [113], [114], [115]]. For instance, Pandit et al. reported an array of graphene flakes grown perpendicularly to the surface by a plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD) process which can effectively prevent the formation of biofilm. The authors proved that the vertically aligned graphene flakes could penetrate the bacterial membrane and drain the cytosolic content, followed by killing the bacteria. Meanwhile, the vertically aligned graphene flakes could prevent the formation of bacterial biofilms, resulting in improved antimicrobial activity. Additionally, this strategy would not induce the microbial drug resistance [112]. Zou et al. synthesized GO with wrinkled surface, which formed “traps” to destroy the bacterial membrane, exhibiting excellent antimicrobial ability [116]. Liu et al. prepared a GO-coating nanosystem which exhibited high antimicrobial activity by produce of oxidative stress [117]. In addition, some controversies about the antimicrobial activity of GBNMs have been reported. For example, Ruiz et al. reported GO didn't possess antimicrobial activity and could induce the increasing of bacteria proliferation [118]. Some studies have been done to clarify this confliction [119]. Palmieri et al. studied the controversy of GO antimicrobial activity in solution, and pointed out the size, doses, morphology, exposure time, and treatment method in the experiment would influence the properties of GO, resulting in different antimicrobial activity [120]. However, the antibacterial mechanisms of GBNMs are mainly summarized to nanoknives, trapping, and oxidative stress.

Inspired by the antimicrobial activity of GBNMs, functionalized GBNMs possess excellent antimicrobial activity due to the synergetic efficacy with other functional materials (e.g. polypeptide, polycationic polymer, lipid) [[121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126]]. Here, we introduced and summarized the antimicrobial activity of GBNMs and functionalized GBNMs as well as the GBNMs-based therapies. For example, GQDs can self-assemble with bacterial amyloid proteins to damage the biofilm of bacteria. GO coated with the metal surface with electron transferring is an effective strategy to disrupt bacteria structure. Metal oxide doped on graphene surface with the metal ions released to kill the bacteria. Therefore, GBNMs-based therapies could be a promising strategy for bacteria-induced infectious diseases treatment.

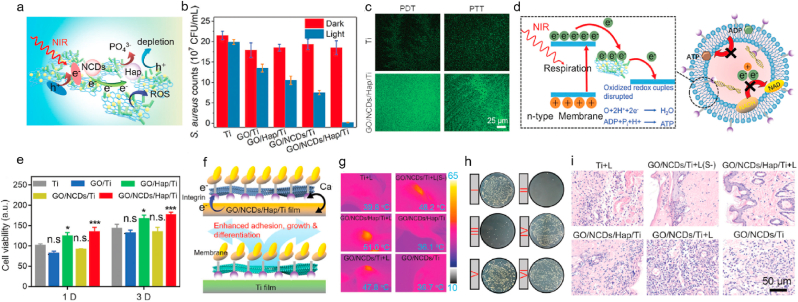

3.1. GBNMs-based antibacterial therapy

GBNMs possess high antimicrobial activity due to their physicochemical properties and unique 2D structure, which can be a promising antibacterial nanomaterial in biomedicine. Li et al. prepared a nitrogen-doped carbon dots (NCDs) and hydroxyapatite (HAP) modified GO heterojunction on titanium (Ti) film (so-called GO/NCD/Hap/Ti) for antibacterial treatment [127]. They evaluated the PDT and PTT efficiency of the GO/NCD/Hap/Ti under NIR irradiation. The results showed that GO/NCD/Hap/Ti could produce abundant ROS with obvious increase of temperature, showing great potential of phototherapy. Fig. 7a showed that the ROS output was caused by the electrons transfer inside the GO/NCD/Hap/Ti and depleting h+ for neutralization of anion from Hap. Then, the antibacterial activity of the GO/NCD/Hap/Ti film was thoroughly investigated, as shown in Fig. 7b. GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti under NIR light treatment possessed the best antimicrobial activity compared with other controls against staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), resulting from the highest level of ROS which could kill the bacteria and played an important role for antimicrobial activity (Fig. 7c). The antibacterial mechanism of GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti with NIR light might be due to the electrons transfer between Ti film and bacteria [128], resulting in high ROS concentration and low production of adenosine triphosphate, which could destruct the bacterial membrane and break bacterial respiration chain, subsequently killing the bacteria (Fig. 7d). Fig. 7e demonstrated that the GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti had high biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity. Additionally, the authors also found GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti with NIR light exhibited tissue reconstruction ability due to the electron transfer between the surface of GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti and bacteria. The electron transfer could promote the Ca2+ flow [129], then induce fast cell migration to reconstruct tissue (Fig. 7f). The phototherapy effect in vivo of GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti for S. aureus was further evaluated. The mice treated with GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti with NIR light showed the highest temperature compared with other controls, as shown in Fig. 7g. The GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti under NIR light treatment showed the highest antimicrobial activity compared with others, as shown in Fig. 7h. Furthermore, GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti under NIR light obviously diminished the inflammatory level in vivo caused by S. aureus (Fig. 7i), and repaired the damage vessels, which were achieved via PLCγ1/ERK and P13K/P-AKT pathways [130,131]. In a word, phototherapy based on GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti in this work possessed great antibacterial activity, high anti-inflammatory ability and vessels repair efficiency in vivo, which could be a promising alternative for antibacterial in the biomaterial field.

Fig. 7.

a. Schematic illustrations of promoted separation of interfacial electrons and holes and inhibited recombination efficiency by and dissociated PO43−. b. The antibacterial efficiency of Ti, GO/Ti, GO/NCDs/Ti, GO/Hap/Ti, and GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti with or without NIR light toward S. aureus. c. The ROS staining toward S. aureus with DCFH-DA probe of Ti and GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti. d. The antibacterial mechanism of GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti plus NIR light. e. The cell viability of Ti, GO/Ti, GO/NCDs/Ti, GO/Hap/Ti, and GO/NCDs/Hap/Ti after one day and three days incubation. f. The mechanism of Ca2+ flow, which can promote cell migration and proliferation as well as ALP enhancement for tissue reconstruction. g. The temperature in vivo after different treatments. h. The spread plates of S. aureus after different treatments, corresponding with (g). i. The H&E staining of infected tissue near the implant after different treatments for one day. Cited and reproduced from the reference [127].

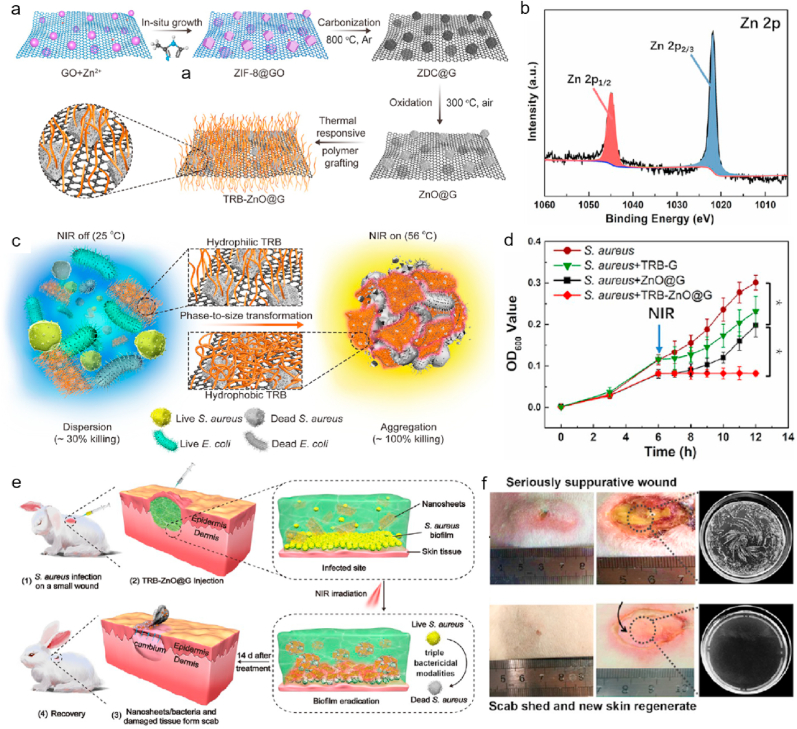

3.2. GBNMs-based therapy for wound healing

GBNMs have become superior antibacterial agency due to its excellent therapeutic efficacy in anti-infection field. In particular, GBNMs also exhibit excellent skin disinfection ability to promote wound healing. Fan and coworkers synthesized a nanosheets (TRB-ZnO@G) which was constructed with graphene, metal-organic-frame and thermal-responsive brushes (TRB) (Fig. 8a) [64]. The XPS Zn 2p spectrum showed the successful synthesis of nanocomposite (Fig. 8b). The authors proved that the TRB-ZnO@G had excellent disinfection ability due to phase-to-size transform properties of TRB. In Fig. 8c, TRB-ZnO@G could change from hydrophilicity to hydrophobicity under NIR irradiation, then wrapped bacteria inside and resulted in aggregation, followed by killing the bacteria (Escherichia coli, E. coli and S. aureus). The antibacterial mechanism might be that bacteria wrapped inside the TRB-ZnO@G could promote Zn2+ release, followed by producing hyperthermal under NIR light which can induce the destruction of bacterial membrane and the death of bacteria [[132], [133], [134]]. Next, the in vitro antibacterial activity of TRB-ZnO@G against S. aureus was performed, and the results were showed in Fig. 8d. Under NIR irradiation, the growth of S. aureus treated with TRB-ZnO@G was significantly suppressed compared with other groups, indicating the highest antimicrobial activity of TRB-ZnO@G. Finally, the authors evaluated the in vivo antimicrobial efficacy of TRB-ZnO@G based in rabbit model with the S. aureus-infected wound (Fig. 8e, PBS with NIR used as control group). In Fig. 8f, a severe infected wound in the rabbits in control group was still obviously observed. By contrast, no obvious suppurative wound in the rabbits treated with TRB-ZnO@G under NIR light was found. Furthermore, the new skin could be observed in the rabbits (bottom), indicating TRB-ZnO@G with NIR light treatment had superior wound healing ability compared with control. In summary, TRB-ZnO@G with NIR light exhibited excellent antibacterial ability and effectively promoted the wound healing, providing a promising strategy in clinic.

Fig. 8.

a. Preparation of TRB-ZnO@G nanosheets. b. XPS spectrum of Zn 2p in TRB-ZnO@G. c. Schematic illustration of phase-to-size transformation of TRB-ZnO@G induced by NIR light, from hydrophilicity to hydrophobicity, bacteria was wrapped inside the TRB-ZnO@G due to the aggregation of TRB-ZnO@G and bacteria (S. aureus and E. coli). d. Real-time OD600 values of S. aureus treated with different treatments (PBS, TRB-G, ZnO@G and TRB-ZnO@G). P-values correspond the date after 6 h, *P < 0.05. e. Schematic illustration of antibacterial measurements of TRB-ZnO@G with NIR light for wound healing based on rabbit model. f. Representative figures of wound sites in rabbits after treatment 14 days: the top was the wound treated with saline plus NIR light, the bottom was the wound treated with TRB-ZnO@G plus NIR light. The two right figures were bacterial colony-forming units of S. aureus from the wound after treatments. Cited and reproduced from the reference [64].

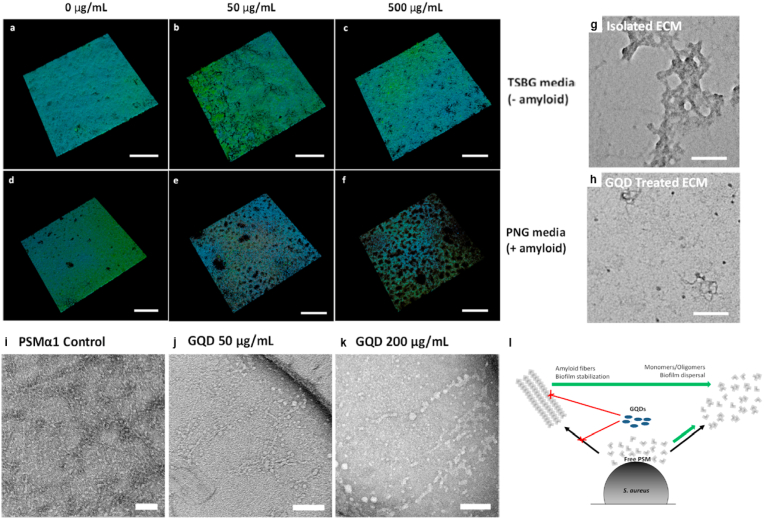

3.3. GBNMs-based anti-biofilms agents for infection management

Anti-infective therapy, as a hot topic in biomedicine field, includes destroy bacterial structure such as cell membrane directly to kill bacteria to receive therapeutic efficacy. Bacterial biofilm exhibits excellent adaptability and recovery ability to environment changes and antibiotics for bacteria, which are huge barrier for antibacterial treatment. Therefore, efficient anti-biofilms agent needs to be developed to enhance therapeutic efficacy of antibacterial treatment. Wang and co-corkers reported GQDs was a superior anti-biofilm agent due to its unique physicochemical properties such as polarizability, amphiphilic character, ability to form hydrogen bonds, and participation in π-π stacking [65]. They suggested GQDs had anti-biofilm activity, it could assembly with bacterial amyloid proteins and destructed biofilms. They studied the influence of GQDs to amyloid-rich biofilms. The biofilms of S. aureus were used as an experimental model and incubated with peptone-NaCl-glucose (PNG) and tryptic soy broth supplemented with glucose (TSBG) media, respectively. TSBG could limit the formation of amyloid. Then, different concentration GQDs were used in these groups, as shown in Fig. 9a–f. The obvious destruct of biofilms in the S. aureus treated with PNG at highest concentration GQDs was found. And the biofilms treated with TSBG at different concentration GQDs showed negligible changes. These results demonstrated that GQDs destructed the biofilms through targeting to amyloid. Extracellular matrix (ECM) was important for biofilms which influenced the properties of biofilms. As seen in Fig. 9g–h, ECM was completely damaged. Then, the authors measured the influence of GQDs to mature amyloids fibers. PSMα1 fibers contained in PSM peptides which could assembly to amyloid fibers to promote ECM mature were used. The matured PSMα1 fibers were treated with GQDs at different concentration, as shown in Fig. 9i–k. The matured PSMα1 fibers treated with highest concentration GQDs were obviously changed and damaged, indicating GQDs could damage the PSM peptides to break biofilms. The anti-biofilms mechanism of GQDs could be that it damaged the functional amyloids by inhibition of fibrillation and destruction of mature amyloid fibers (Fig. 9l) [135]. In this work, GQDs exhibited great anti-biofilm capability, which was a promising anti-biofilms agent to enhance the efficacy of anti-infection therapy.

Fig. 9.

a−c. Confocal microscopy of S. aureus biofilm incubated with TSBG media with different concentration GQDs. Scale bar: 200 μm. d-f. Confocal microscopy of S. aureus biofilm incubated with PNG media with different concentration GQDs. Scale bar: 200 μm. g-h. ECM extracted from S. aureus biofilm treated without or with 50 μg/mL GQDs, Scale bar: 100 nm. i-k. TEM images of matured PSMα1 fibers treated with GQDs in different concentrations. Scale bars: 100 nm. l. The schematic of GQDs interact with PSM peptides. Cited and reproduced from the reference [61].

4. Summary and perspective

In this review, we summarize the recent updates related to GBNMs for cancer and infectious diseases treatments, indicating GBNMs is a promising candidate in biomedicine field. For cancer therapy, phototherapy has attracted more and more attention due to improved therapeutic efficacy and reduced side effect. GBNMs exhibit excellent photothermal conversion effect under light irradiation and has been used as a potential PTA. In addition, GQDs possess the ability to generate ROS under light irradiation and has been considered as a novel PS agent. Furthermore, GO and rGO become superior chemical drug or gene delivery carrier due to the large surface area and easy functionalized properties. Therefore, combination therapy based on GBNMs has been widely developed in recent years. For example, the combination of PTT and chemotherapy has an enhanced therapeutic efficacy, GO and rGO are used as vehicle for target delivery of cargos to tumor site. Under light irradiation, local hyperthermia induced by PTT could significantly improve the drug release profile and enhance the cellular uptake of cargos by tumor cells. For PTT and RT combination therapy, the oxygen-deficient microenvironment of tumor cells is the major obstacle for RT, whereas local hyperthermia induced by PTT can improve intratumor oxygenation to increase cells sensitivity to RT, which can effectively enhance the therapeutic effect of RT effectively.

Furthermore, it is reported that PDT could accelerate the release of tumor cells debris and then stimulate antitumor immunity, which activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes and infiltrate into the cancer cells to damage residual cancer cells to prevent metastasis. Therefore, the combination of PDT and immunotherapy can obtain enhanced therapeutic efficacy for cancer. Finally, it is confirmed that GBNMs-based multiple therapy also exhibits excellent ability to inhibit tumor growth. From above discuss, we believe GBNMs is a promising candidate for cancer therapy in the future. For anti-infection therapy, GBNMs exhibits high antibacterial activity to cure infectious diseases. GBNMs exhibit the ability to transfer electrons from bacterial cells resulting in damage to bacterial and then generate ROS to suppress bacteria. GBNMs also exhibit excellent skin disinfection to promote wound healing, and it can wrap bacteria and kill them under NIR irradiation following the generation of metal ions, physical cutting and hyperthermal. What's more, GBNMs exhibits excellent ability to disperse biofilms of bacteria, which exhibit strong adaptability and fast recovery to environmental and medicine. In brief, GBNMs and GBNMs-based therapies can effectively inhibit bacteria and damage bacteria structure due to its excellent physicochemical properties and unique structure.

Here, GBNMs-based treatment strategies showed high therapeutic efficacy and reduced side effect in cancer therapy and bacteria-induced infectious diseases treatment due to the excellent physicochemical properties and unique structure. However, there are still some challenges or limitations of GBNMs in both cancer and bacteria-induced infectious diseases treatments before clinical use. First, the biosafety of GBNMs-based therapies should be concerned and thoroughly investigated before wide use in clinic. The body reactions after long-term use of GBNMs are different for everyone. More long-term experiments need to be completed and evaluated to make sure the biosafety of GBNMs. For example, it needs high doses of drugs to get better therapeutic efficacy for patients, but some studies showed that high doses of GBNMs in body were harmful to organs like kidney and liver [136]. The particle size of GBNMs in body also is an important factor for the patient. As reported, the big size of GBNMs can cause inflammation which could induce the aggravation of cancer or infections [137]. In addition, there will be some residual chemicals in the preparation process of GBNMs, which could cause a certain burden in body [138]. Therefore, the biosafety of GBNMs-based therapies is the most important issue for the clinical use of GBNMs. Second, most GBNMs used in biomedical fields are functionalized/modified via complex procedures, following the strict requirements for each step. It will take a long time to prepare the multi-functional GBNMs with high quality that can be used in vivo. To make sure the component of functionalized GBNMs in each batch consistent completely is the basic requirement for the clinical application, which is time-consuming and expensive. So, it brings great challenges to scale-up produce in practice applications. Furthermore, considering the influence of type and quality (size and purity) on the physicochemical properties of GBNMs, the preparation process of GBNMs and the purity, state, and dosage of raw materials should be focused and rigidly controlled. Third, the mechanism of antimicrobial activity of GBNMs is not clear so far [[139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145]]. More efforts and further researches should be promoted to investigate the mechanism of antimicrobial activity of GBNMs for the clinic applications in future. Fourth, GBNMs have become potential nanomaterials in many biomedical fields. So, the wide clinic use will need quantity production of GBNMs, which will raise concern about the influence in environment. Ahmed et al. reported that GO-based waste could influence the bacterial metabolic activity, enhance the turbidity of effluent and reduce the dewaterability of sludge [146]. Finally, the evaluations of therapeutic efficacy of GBNMs are mainly based on small animals like mouse. More experiments in vivo should be completed to further confirm the therapeutic efficacy of GBNMs before clinic use. Herein, it's a long way to promoting the wide clinic use of GBNMs.

Although there are some challenges and limitations of GBNMs for the clinic use, GBNMs have great potential in many biomedical fields. The method to obtain high-quality GBNMs is the main problem facing now. The synthesis processes of GBNMs used in the experiment are generally complicated and only suitable for small-scale production. For some multi-functional GBNMs, the surface modification processes are difficult to control accurately, especially the chemical modification with functional organic polymer. The functionalization using noncovalent, such as π-π stacking, van der Waals interaction, electrostatic interaction, and hydrogen bond, the interaction force between them is not strong enough. In the functionalization process, it is difficult to guarantee accurate numbers of functional groups, causing huge challenges for quantity production. Therefore, synthesis process and preparation procedure are the key issues that needs to be solved urgently. Additionally, the antibacterial mechanism of GBNMs is not understood well. As reported, not all GBNMs exhibited antimicrobial activity in the experiments. On the contrary, some GBNMs were proved to enhance the growth of bacteria in some studies. Phototherapy based on GBNMs possesses great therapeutic efficacy, but the side effect (biosafety) of phototherapy is still controversial. Although many studies point out that phototherapy will not damage normal cells, some references reported that phototherapy can cause the damage of normal cells and tissues like blood vessels. However, GBNMs, as a 2D material with unique structure and excellent properties, is one of most promising nanomaterials in many biomedical fields. We encourage more efforts and researches should be devoted to develop great GBNMs and GBNMs-based therapy strategies with improved therapeutic efficacy, reduced side-effect and enhanced biosafety for different diseases treatment.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Scientific Research Start-up Funds (No. QD2021020C, No. 01010600002) at Shenzhen International Graduate School at Tsinghua University, Research Fund Program of Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Green Chemical Product Technology, China (No. 03021300001) and National Natural Science Foundation of China, China (No. 21902012).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Zhong Y., Zhen Z., Zhu H. Graphene: fundamental research and potential applications. FlatChem. 2017;4:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren S., Rong P., Yu Q. Preparations, properties and applications of graphene in functional devices: a concise review. Ceram. Int. 2018;44(11):11940–11955. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palejwala A.H., Fridley J.S., Mata J.A., Samuel E.L.G., Jea A. Biocompatibility of reduced graphene oxide nanoscaffolds following acute spinal cord injury in rats. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2016;7(1):75. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.188905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z., Zeng H., Sun L. Graphene quantum dots: versatile photoluminescence for energy, biomedical, and environmental applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2015;3(6):1157–1165. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari M., Gauthaman K., Essa A., Bencherif S., Memic A. Graphene and graphene-based materials in biomedical applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019;26(38):6834–6850. doi: 10.2174/0929867326666190705155854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung C., Kim Y.K., Shin D., Ryoo S.R., Min D.H. Biomedical applications of graphene and graphene oxide. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46(10):2211–2224. doi: 10.1021/ar300159f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priya Swetha P.D., Manisha H., Sudhakaraprasad K. Graphene and graphene‐based materials in biomedical science. Part. Part. Syst. Char. 2018;35(8):1800105. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng X.T., Ananthanarayanan A., Luo K.Q., Chen P. Glowing graphene quantum dots and carbon dots: properties, syntheses, and biological applications. Small. 2015;11(14):1620–1636. doi: 10.1002/smll.201402648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkless L. Graphene quantum dots for multiple biomedical applications. Mater. Today. 2016;19(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y., Asiri A.M., Tang Z., Du D., Lin Y. Graphene based materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Today. 2013;16(10):365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangalath S., Saneesh Babu P.S., Nair R.R., Manu P.M., Krishna S., Nair S.A., Joseph J. Graphene quantum dots decorated with boron dipyrromethene dye derivatives for photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021;4(4):4162–4171. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan H.-y., Yu X.-h., Wang K., Yin Y.-j., Tang Y.-j., Tang Y.-l., Liang X.-h. Graphene quantum dots (GQDs)-based nanomaterials for improving photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;182:111620. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panáček, D.; Hochvaldová, L.; Bakandritsos, A.; Malina, T.; Langer, M.; Belza, J.; Martincová, J.; Večeřová, R.; Lazar, P.; Poláková, K., Silver covalently bound to cyanographene overcomes bacterial resistance to silver nanoparticles and antibiotics. Adv. Sci. 2021, 2003090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Yan X., Hu H., Lin J., Jin A.J., Niu G., Zhang S., Huang P., Shen B., Chen X. Optical and photoacoustic dual-modality imaging guided synergistic photodynamic/photothermal therapies. Nanoscale. 2015;7(6):2520–2526. doi: 10.1039/c4nr06868h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou F., Wang M., Luo T., Qu J., Chen W.R. Photo-activated chemo-immunotherapy for metastatic cancer using a synergistic graphene nanosystem. Biomaterials. 2021;265:120421. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Z.-C., Wang M., Yong A.M., Wong S.Y., Zhang X.-H., Tan H., Chang A.Y., Li X., Wang J. Intrinsically fluorescent carbon dots with tunable emission derived from hydrothermal treatment of glucose in the presence of monopotassium phosphate. Chem. Commun. 2011;47(42):11615–11617. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14860e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H., Kang Z., Liu Y., Lee S.-T. Carbon nanodots: synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2012;22(46):24230–24253. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talib A., Pandey S., Thakur M., Wu H.-F. Synthesis of highly fluorescent hydrophobic carbon dots by hot injection method using Paraplast as precursor. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2015;48:700–703. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian B., Wang C., Zhang S., Feng L., Liu Z. Photothermally enhanced photodynamic therapy delivered by nano-graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):7000–7009. doi: 10.1021/nn201560b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson J.T., Tabakman S.M., Liang Y., Wang H., Sanchez Casalongue H., Vinh D., Dai H. Ultrasmall reduced graphene oxide with high near-infrared absorbance for photothermal therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(17):6825–6831. doi: 10.1021/ja2010175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popat K., Mcqueen K., Feeley T.W. The global burden of cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2013;27(4):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sener S.F., Grey N. The global burden of cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005;92(1):1–3. doi: 10.1002/jso.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li R., Huang Y., Lin J. Distinct effects of general anesthetics on lung metastasis mediated by IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway in mouse models. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):642. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14065-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wild C.P. The global cancer burden: necessity is the mother of prevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19(3):123–124. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Z., Yan Y., Wang L., Zhang Q., Cheng Y. Melanin-like nanoparticles decorated with an autophagy-inducing peptide for efficient targeted photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;203:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W., Jing T., Xia X., Tang L., Huang Z., Liu F., Wang Z., Ran H., Li M., Xia J. Melanin-loaded biocompatible photosensitive nanoparticles for controlled drug release in combined photothermal-chemotherapy guided by photoacoustic/ultrasound dual-modality imaging. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7(10):4060–4074. doi: 10.1039/c9bm01052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A P.V. Tumor microenvironmental physiology and its implications for radiation oncology. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2004;14(3):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie J., Gong L., Zhu S., Yong Y., Gu Z., Zhao Y. Emerging strategies of nanomaterial‐mediated tumor radiosensitization. Adv. Mater. 2019;31(3):1802244. doi: 10.1002/adma.201802244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirk M.D., Pires S.M., Black R.E., Caipo M., Crump J.A., Devleesschauwer B., Döpfer D., Fazil A., Fischer-Walker C.L., Hald T. World Health Organization estimates of the global and regional disease burden of 22 foodborne bacterial, protozoal, and viral diseases, 2010: a data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2015;12(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arciola C.R., Campoccia D., Montanaro L. Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16(7):397–409. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy S.B., Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 2004;10(12):S122–S129. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alekshun M.N., Levy S.B. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance. Cell. 2007;128(6):1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J.-K., Mereuta L., Luchian T., Park Y. Antimicrobial peptide HPA3NT3-A2 effectively inhibits biofilm formation in mice infected with drug-resistant bacteria. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7(12):5068–5083. doi: 10.1039/c9bm01051c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Álvarez-Lerma F., Olaechea-Astigarraga P., Palomar-Martínez M., Catalan M., Nuvials X., Gimeno R., Gracia-Arnillas M.P., Seijas-Betolaza I., Group E.-H.S. Invasive device-associated infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in critically ill patients: evolution over 10 years. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018;100(3):e204–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L., Zhou L., Wang C., Han Y., Dong C. Tumor-targeted drug and CpG delivery system for phototherapy and docetaxel-enhanced immunotherapy with polarization toward M1-type macrophages on triple negative breast cancers. Adv. Mater. 2019;31(52) doi: 10.1002/adma.201904997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao J., Chen Z., Chi J., Sun Y., Sun Y. Recent progress in synergistic chemotherapy and phototherapy by targeted drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018;46(sup1):817–830. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2018.1436553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J., Hou M., Sun W., Wu Q., Xu J., Xiong L., Chai Y., Liu Y., Yu M., Wang H. Sequential PDT and PTT using dual‐modal single‐walled carbon nanohorns synergistically promote systemic immune responses against tumor metastasis and relapse. Adv. Sci. 2020;7(16):2001088. doi: 10.1002/advs.202001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courtney C.M., Goodman S.M., Nagy T.A., Levy M., Bhusal P., Madinger N.E., Detweiler C.S., Nagpal P., Chatterjee A. Potentiating antibiotics in drug-resistant clinical isolates via stimuli-activated superoxide generation. Sci. Adv. 2017;3(10) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J., Liu X., Tan L., Liang Y., Cui Z., Yang X., Zhu S., Li Z., Zheng Y., Yeung K.W.K. Light‐activated rapid disinfection by accelerated charge transfer in red phosphorus/ZnO heterointerface. Small Methods. 2019;3(3):1900048. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long Z., Dai J., Hu Q., Wang Q., Zhen S., Zhao Z., Liu Z., Hu J.-J., Lou X., Xia F. Nanococktail based on AIEgens and semiconducting polymers: a single laser excited image-guided dual photothermal therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10(5):2260–2272. doi: 10.7150/thno.41317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Q., Guo Q., Chen Q., Zhao X., Pennycook S.J., Chen H. Highly efficient 2D NIR‐II photothermal agent with fenton catalytic activity for cancer synergistic photothermal–chemodynamic therapy. Adv. Sci. 2020;7(7):1902576. doi: 10.1002/advs.201902576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi J., Li J., Wang Y., Cheng J., Zhang C.Y. Recent advances in MoS2-based photothermal therapy for cancer and infectious disease treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020;8(27):5793–5807. doi: 10.1039/d0tb01018a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen J., Ning C., Zhou Z., Yu P., Zhu Y., Tan G., Mao C. Nanomaterials as photothermal therapeutic agents. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019;99:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C., Chen P., Qiao Y., Kang Y., Yan C., Yu Z., Wang J., He X., Wu H. pH responsive superporogen combined with PDT based on poly Ce6 ionic liquid grafted on SiO2 for combating MRSA biofilm infection. Theranostics. 2020;10(11):4795. doi: 10.7150/thno.42922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan Y., Lu G., Wei W.-C., Huang Y.-H., Li S., Chen J.-X., Cui X., Xiao Y.-F., Li X., Liu Y. Stable organic photosensitizer nanoparticles with absorption peak beyond 800 nanometers and high reactive oxygen species yield for multimodality phototheranostics. ACS Nano. 2020;14(8):9917–9928. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi X., Zhang C.Y., Gao J., Wang Z. Recent advances in photodynamic therapy for cancer and infectious diseases. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019;11(5) doi: 10.1002/wnan.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu J.-J., Lei Q., Zhang X.-Z. Recent advances in photonanomedicines for enhanced cancer photodynamic therapy. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020;114:100685. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang K., Zhang S., Zhang G., Sun X., Lee S.-T., Liu Z. Graphene in mice: ultrahigh in vivo tumor uptake and efficient photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 2010;10(9):3318–3323. doi: 10.1021/nl100996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Markovic Z.M., Harhaji-Trajkovic L.M., Todorovic-Markovic B.M., Kepić D.P., Arsikin K.M., Jovanović S.P., Pantovic A.C., Dramićanin M.D., Trajkovic V.S. In vitro comparison of the photothermal anticancer activity of graphene nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2011;32(4):1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lima-Sousa R., de Melo-Diogo D., Alves C.G., Costa E.C., Ferreira P., Louro R.O., Correia I.J. Hyaluronic acid functionalized green reduced graphene oxide for targeted cancer photothermal therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;200:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thakur M., Kumawat M.K., Srivastava R. Multifunctional graphene quantum dots for combined photothermal and photodynamic therapy coupled with cancer cell tracking applications. RSC Adv. 2017;7(9):5251–5261. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu S., Pan X., Liu H. Two‐dimensional nanomaterials for photothermal therapy. Angew. Chem. 2020;132(15):5943–5953. doi: 10.1002/anie.201911477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Y.-W., Su Y.-L., Hu S.-H., Chen S.-Y. Functionalized graphene nanocomposites for enhancing photothermal therapy in tumor treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;105:190–204. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ge J., Lan M., Zhou B., Liu W., Guo L., Wang H., Jia Q., Niu G., Huang X., Zhou H. A graphene quantum dot photodynamic therapy agent with high singlet oxygen generation. Nat. Commun. 2014;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabish T.A., Scotton C.J., J Ferguson D.C., Lin L., der Veen A.v., Lowry S., Ali M., Jabeen F., Ali M., Winyard P.G. Biocompatibility and toxicity of graphene quantum dots for potential application in photodynamic therapy. Nanomedicine. 2018;13(15):1923–1937. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markovic Z.M., Ristic B.Z., Arsikin K.M., Klisic D.G., Harhaji-Trajkovic L.M., Todorovic-Markovic B.M., Kepic D.P., Kravic-Stevovic T.K., Jovanovic S.P., Milenkovic M.M. Graphene quantum dots as autophagy-inducing photodynamic agents. Biomaterials. 2012;33(29):7084–7092. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramirez-Garcia A., Rementeria A., Aguirre-Urizar J.M., Moragues M.D., Antoran A., Pellon A., Abad-Diaz-de-Cerio A., Hernando F.L. Candida albicans and cancer: can this yeast induce cancer development or progression? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;42(2):181–193. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2014.913004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawanishi S., Ohnishi S., Ma N., Hiraku Y., Oikawa S., Murata M. Nitrative and oxidative DNA damage in infection-related carcinogenesis in relation to cancer stem cells. Gene Environ. 2016;38(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s41021-016-0055-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Elsland D., Neefjes J. Bacterial infections and cancer. EMBO Rep. 2018;19(11) doi: 10.15252/embr.201846632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao H., Ding R., Zhao X., Li Y., Qu L., Pei H., Yildirimer L., Wu Z., Zhang W. Graphene-based nanomaterials for drug and/or gene delivery, bioimaging, and tissue engineering. Drug Discov. Today. 2017;22(9):1302–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu J., Yuan X., Deng L., Yin Z., Tian X., Bhattacharyya S., Liu H., Luo Y., Luo L. Graphene oxide activated by 980 nm laser for cascading two-photon photodynamic therapy and photothermal therapy against breast cancer. Appl. Mater. Today. 2020;20:100665. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaharie-Butucel D., Potara M., Suarasan S., Licarete E., Astilean S. Efficient combined near-infrared-triggered therapy: phototherapy over chemotherapy in chitosan-reduced graphene oxide-IR820 dye-doxorubicin nanoplatforms. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;552:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romero M.P., Marangoni V.S., de Faria C.G., Leite I.S., Maroneze C.M., Pereira-da-Silva M.A., Bagnato V.S., Inada N.M. Graphene oxide mediated broad-spectrum antibacterial based on bimodal action of photodynamic and photothermal effects. Front. Microbiol. 2020;10:2995. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fan X., Yang F., Huang J., Yang Y., Nie C., Zhao W., Ma L., Cheng C., Zhao C., Haag R. Metal–organic-framework-derived 2D carbon nanosheets for localized multiple bacterial eradication and augmented anti-infective therapy. Nano Lett. 2019;19(9):5885–5896. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y., Kadiyala U., Qu Z., Elvati P., Altheim C., Kotov N.A., Violi A., VanEpps J.S. Anti-biofilm activity of graphene quantum dots via self-assembly with bacterial amyloid proteins. ACS Nano. 2019;13(4):4278–4289. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu S., Zhang J., Qiao C., Tang S., Li Y., Yuan W., Li B., Tian L., Liu F., Hu R. Strongly green-photoluminescent graphene quantum dots for bioimaging applications. Chem. Commun. 2011;47(24):6858–6860. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11122a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu H., Li C., Qian Y., Hu L., Fang J., Tong W., Nie R., Chen Q., Wang H. Magnetic-induced graphene quantum dots for imaging-guided photothermal therapy in the second near-infrared window. Biomaterials. 2020;232:119700. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.He S., Song J., Qu J., Cheng Z. Crucial breakthrough of second near-infrared biological window fluorophores: design and synthesis toward multimodal imaging and theranostics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47(12):4258–4278. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00234g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang H., Mu Q., Wang K., Revia R.A., Yen C., Gu X., Tian B., Liu J., Zhang M. Nitrogen and boron dual-doped graphene quantum dots for near-infrared second window imaging and photothermal therapy. Appl. Mater. Today. 2019;14:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tang L., Ji R., Li X., Bai G., Liu C.P., Hao J., Lin J., Jiang H., Teng K.S., Yang Z. Deep ultraviolet to near-infrared emission and photoresponse in layered N-doped graphene quantum dots. ACS Nano. 2014;8(6):6312–6320. doi: 10.1021/nn501796r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sherlock S.P., Tabakman S.M., Xie L., Dai H. Photothermally enhanced drug delivery by ultrasmall multifunctional FeCo/graphitic shell nanocrystals. ACS Nano. 2011;5(2):1505–1512. doi: 10.1021/nn103415x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dong K., Liu Z., Li Z., Ren J., Qu X. Hydrophobic anticancer drug delivery by a 980 nm laser‐driven photothermal vehicle for efficient synergistic therapy of cancer cells in vivo. Adv. Mater. 2013;25(32):4452–4458. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang H., Chen J., Li N., Jiang R., Zhu X.-M., Wang J. Au nanobottles with synthetically tunable overall and opening sizes for chemo-photothermal combined therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(5):5353–5363. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ma J., Li P., Wang W., Wang S., Pan X., Zhang F., Li S., Liu S., Wang H., Gao G. Biodegradable poly (amino acid)–gold–magnetic complex with efficient endocytosis for multimodal imaging-guided chemo-photothermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12(9):9022–9032. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu C., Feng Q., Yang H., Wang G., Huang L., Bai Q., Zhang C., Wang Y., Chen Y., Cheng Q. A light‐triggered mesenchymal stem cell delivery system for photoacoustic imaging and chemo‐photothermal therapy of triple negative breast cancer. Adv. Sci. 2018;5(10):1800382. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Y., Hu J., Xiang D., Peng X., You Q., Mao Y., Hua D., Yin J. Targeted nanosystem combined with chemo-photothermal therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020;596:124711. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qi W., Yan J., Sun H., Wang H. Nanocomposite plasters for the treatment of superficial tumors by chemo-photothermal combination therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018;13:6235–6247. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S170209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lucherelli M.A., Yu Y., Reina G., Abellán G., Miyako E., Bianco A. Rational chemical multifunctionalization of graphene interface enhances targeted cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. 2020;132(33):14138–14143. doi: 10.1002/anie.201916112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qu G., Wang X., Liu Q., Liu R., Yin N., Ma J., Chen L., He J., Liu S., Jiang G. The ex vivo and in vivo biological performances of graphene oxide and the impact of surfactant on graphene oxide's biocompatibility. J. Environ. Sci. 2013;25(5):873–881. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(12)60252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wen K.P., Chen Y.C., Chuang C.H., Chang H.Y., Lee C.Y., Tai N.H. Accumulation and toxicity of intravenously‐injected functionalized graphene oxide in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015;35(10):1211–1218. doi: 10.1002/jat.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Syama S., Paul W., Sabareeswaran A., Mohanan P.V. Raman spectroscopy for the detection of organ distribution and clearance of PEGylated reduced graphene oxide and biological consequences. Biomaterials. 2017;131:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ledermann J., Canevari S., Thigpen T. Targeting the folate receptor: diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to personalize cancer treatments. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26(10):2034–2043. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paunesku T., Gutiontov S., Brown K., Woloschak G.E. Nanotechnology-Based Precision Tools for the Detection and Treatment of Cancer. 2015. Radiosensitization and nanoparticles; pp. 151–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou R., Wang H., Yang Y., Zhang C., Dong X., Du J., Yan L., Zhang G., Gu Z., Zhao Y. Tumor microenvironment-manipulated radiocatalytic sensitizer based on bismuth heteropolytungstate for radiotherapy enhancement. Biomaterials. 2019;189:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee M.H., Yang Z., Lim C.W., Lee Y.H., Dongbang S., Kang C., Kim J.S. Disulfide-cleavage-Triggered chemosensors and their biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2013;113(7):5071–5109. doi: 10.1021/cr300358b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lin H., Chen Y., Shi J. Nanoparticle-triggered in situ catalytic chemical reactions for tumour-specific therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47(6):1938–1958. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00471k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]