Abstract

This paper presents a dynamic system for estimating the spreading profile of COVID-19 in Thailand, taking into account the effects of vaccination and social distancing. For this purpose, a compartmental network is built in which the population is divided into nine mutually exclusive nodes, including susceptible, insusceptible, exposed, infected, vaccinated, recovered, quarantined, hospitalized, and dead. The weight of edges denotes the interaction between the nodes, modeled by a series of conversion rates. Next, the compartmental network and corresponding rates are incorporated into a system of fractional partial differential equations to define the model governing the problem concerned. The fractional degree corresponding to each compartment is considered the node weight in the proposed network. Next, a Monte Carlo-based optimization method is proposed to fit the fractional compartmental network to the actual COVID-19 data of Thailand collected from the World Health Organization. Further, a sensitivity analysis is conducted on the node weights, i.e., fractional orders, to reveal their effect on the accuracy of the fit and model predictions. The results show that the flexibility of the model to adapt to the observed data is markedly improved by lowering the order of the differential equations from unity to a fractional order. The final results show that, assuming the current pandemic situation, the number of infected, recovered, and dead cases in Thailand will, respectively, reach 4300, , and 36,000 by the end of 2021.

Introduction

The mathematical modeling of infectious diseases has been the foundation of infectious disease epidemiology for more than a century [1]. In recent years, detailed scrutiny of such diseases has become extensive because of improvements in data analysis, computing methods, diagnostic tests, and genome sequencing. Advances in such methods enable researchers to deploy mathematical models to design practical schemes for disease control, and also develop and test mathematical and statistical methods [2–6]. Mathematical models that describe the spread of diseases are continually being developed and are playing a fundamental role in promoting public health strategies in many countries [7–10].

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus, officially called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO), led to an outbreak of atypical pneumonia, first in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province in China, and then expeditiously flared out in the entire world [11]. As of October 01, 2021, there have been more than 230 million confirmed cases, together with nearly 4.8 million deaths reports in the world [12]. Throughout anti-epidemic struggles, apart from medical, biological, and scientific research, theoretical studies based on mathematical and statistical modeling may thus significantly contribute to the conception of outbreak attributes [13–15]. Forecasting the trajectory of the spread accordingly helps countries make informed decisions on the required actions to mitigate the spread of the disease.

Different models have thus far been proposed to analyze COVID-19, but compartmental methods that divide the population into compartments have dominated epidemiological modeling area [16–19]. These models assist in interpreting the way COVID-19 spreads and in forecasting regional pinnacles of the pandemic. Compartmental models are broadly based on studying the systems of differential equations. In this respect, differential equations concentrate on the rate of changes in a variable or a group of variables as time proceeds. The most common model is the SIR, which divides a population into susceptible (S), infected (I), and recovered (R). The popularity of this model stems from its simplicity in predicting a small number of parameters. There are a number of studies that predict the spread of COVID-19 by this method, e.g., see [20, 21], and [22].

Various models have been similarly extracted from the basic SIR model, which have thus far supplemented additional compartments to the SIR model [23]. One of the valuable models is the SEIR, namely, the susceptible-exposed-infected-recovered model, which has added the exposed compartment to the SIR structure [24]. The exposed group refers to the phase between the susceptible and the infected individuals. It comprises the population exposed to an infection but not yet infected. The SEIR model is thus capable of analyzing the spread of diseases more accurately than the basic SIR model [25]. Of note, a host of studies have analyzed the COVID-19 pandemic through modified versions of the SEIR model, e.g., see [26, 27] and [28].

Some studies have proposed the fractional SIR model, where one or, feasibly, both sub-compartments are raised by exponents that are usually less than unity [29]. The reason is that the infection transmits outwards from an infected population to the whole population through the early stages of an epidemic. Within this framework, where susceptible is much greater than infected it is better to scale them as a fractional power. Given the decreasing number of infected people over the general population in real world, the exponent is anticipated to be larger than 1/2. Furthermore, the power of the susceptible population, which is notably higher than that of the infected population, may be negligible at least in the initial stages of an epidemic.

Deploying fractional exponents stemmed from a growth model, called the Norton–Simon–Massagué (NSM) model [30]. This model was created to explain the growth of biological organisms through applying determined energy principles. The governing differential equation reads

| 1 |

where and measure anabolism growth and defuse, respectively. Equation 1 may be simplified as declaring the net growth rate of a biological organism outcome of the balance between synthetic and degradative mechanisms. Meanwhile, the rate is proportional to the growth volume G(t) with a power function and the rate of the latter process relates linearly with G(t). It is thus vital to mention that the two exceptional cases of Eq. 1 are power-law, where , and second-type growth, where , to explain the tumor growth [31]. Different types of fractional compartmental models have been applied to a number of infectious diseases, e.g., see [32–38].

Despite the fact that these models are convincing instruments and typically allow practical intuition into grasping the growth and the spread of diseases within designated populations, they suffer from one major flaw; that is, with the increase of the number of compartments, the number of model parameters increases, making it difficult for the model to properly fit the data. In other words, there is a trade-off between increasing the computational node and the regression accuracy. To cover new aspects of the problem, such as quarantine, hospitalization, and vaccination, it is necessary to add new components to the problem to make model more realistic [39, 40]. This, on the other hand, increases the number of model parameters, greatly adds to the complexity of the problem, and in turn reduces the accuracy of the fit.

To address this issue, this paper puts forward a time-variant SEIVR-QH network, comprised of nine nodes: (1) susceptible, (2) insusceptible, (3) vaccinated, (4) exposed, (5) infected, (6) quarantined, (7) recovered, (8) hospitalized and (9) dead. In a novel development, the differential equation is expressed in fractional form, described shortly. The conventional form of compartmental networks employs first-order differential equations. In contrast, introducing the fractional form here in this paper facilitates the formulation of differential equations in non-integer, fractional orders, which leads to significant flexibility for the model to describe the observed data. This model has several unknown parameters that must be estimated to fit the model to the actual data. It requires a multi-objective optimization to select the optimal parameters by minimizing the error between the actual data and the model outputs. In addition, this optimization process requires solving the system of fractional differential equations in each iteration which is a complex task. To this end, a two-step back analysis is proposed in this paper based on Monte Carlo sampling. A comparison is made here between the capability of the proposed method and that of other optimization techniques, such as the particle swarm optimization (PSO) used in [41]. First, PSO is a deterministic optimization algorithm and Monte Carlo sampling is an inherently probabilistic method. In other words, the system parameters in the latter are modeled as random variables. The back analysis proposed in this study is a two-step algorithm. That is, first, the Monte Carlo sampling method is used to identify the samples that lead to the closest realizations to the target time histories. The results are then introduced into the second stage of the back-analysis algorithm to obtain the optimal parameters. This leads to the probabilistic characteristics of the optimal model parameters, such as the mean and standard deviation, using the output of the first step. In addition, the deterministic optimal parameters can be obtained as the mean values. Therefore, the proposed back analysis can provide both probabilistic and deterministic parameters, while the PSO method only yields optimal deterministic results. Second, the modeling approach in the present paper is based on the fractional form of the system of differential equations. The performance of PSO in the optimization of fractional equations has not yet been evaluated. In contrast, Monte Carlo sampling method is robust in handling such complex systems of fractional networks proposed in this study. Finally, the fractional order of the proposed differential equations also needs to be optimized along with other model parameters. Hence, the problem here involves differential equations of varying order, which is intractable in the classical PSO. That is, the classical PSO does not allow the optimization of the order of differential equations as the change in the order will fundamentally change the objective function and affect the process of calculating the cost function. In contrast, Monte Carlo sampling is based on the generation of random samples and the fractional order is yet another random variable in this analysis, which can be readily handled.

The content of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the proposed time-variant fractional SEIVR-QH network is presented, and the deterministic form of the problem is formulated. In Sect. 3, the main framework of the Monte Carlo-based back analysis is introduced and applied to the actual data of Thailand. In Sect. 4, a sensitivity analysis [42] is conducted to investigate the influence of the fractional order of the differential equation on the regression accuracy. Finally, the research is summarized and concluded in Sect. 5.

Deterministic fractional SEIVR-QH network

Fractional calculus

In this paper, the modeling formulation is derived by the Caputo derivative in fractional calculus. Several researchers have applied fractional derivatives in science and engineering, e.g., see [43].

Definition 1

Given a positive real number and an integrable function , the fractional integral of f of order is defined as [44]:

| 2 |

where denotes the Gamma function.

Definition 2

The Caputo fractional derivative, where , is defined as [44]:

| 3 |

If f is a function of class , its fractional derivative is represented by the following expression:

| 4 |

where represents the Gamma function.

Deterministic SEIVR-QH network

In this paper, an extended fractional SEIR network, called the SEIVR-QH, is applied to develop a deterministic model for the spread of COVID-19. In the definition of this network, the population is divided into nine nodes. First, the whole population is considered susceptible (S), which can become exposed (E) or can be immunized by observing social distancing (P) or being vaccinated (V) against the disease. Depending on the social exposure, exposed cases can be transmitted to the infected stage (I). If an individual is diagnosed with the disease, they will be quarantined (Q) based on the disease severity and infection spread. If the infection is severe, the patient will then be hospitalized (H). Consequent to treatment via hospital-based medical care or self-medication, nearly all quarantined cases recover (R) and some die (D) because of the disease severity. The relationship between these nine states is depicted in the network shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between different nodes

The mathematical relationships among the nine states in the model are expressed by a system of fractional differential equations, as follows:

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

where is the protection rate, indicates the infection rate, stands for the vaccination rate, is the average latency time, denotes the rate at which infected cases enter into quarantine, refers to hospitalization rate, is the time-variant quarantine recovery rate, is the time-variant mortality quarantine rate, and and are hospitalization recovery and mortality rates, respectively. The constraint , , is applied, where N is the entire target population.

Theorem 1

There is a unique solution for the fractional SEIVR-QH model. Moreover, the solution is non-negative.

Proof

Let and for , f(x) is the Lebesgue measure. Then,

| 15 |

with , . If , then the function f is non-decreasing, and if , then the function f is non-increasing for all . Afterwards, all the conditions in Theorem 3.1 from [45] are met and there is a unique and non-negative function in , which is the solution of Eq. (1). There is also a need to show that the domain is positively invariant. Since the following holds:

| 16 |

on each hyper-plane bounding the non-negative orthant, the vector field points into .

Theorem 2

Consider the initial value problem ofEqs. (5)–(14), with satisfying , to evaluate its equilibrium points. Let

| 17 |

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

| 21 |

| 22 |

| 23 |

| 24 |

| 25 |

Then, the equilibrium points are

A disease-free equilibrium

An endemic equilibrium point , where , , and .

Numerical solution

The system of fractional differential equations is written in the matrix form, as follows:

| 26 |

| 27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

To solve the matrix form of the given system, the Adams–Bashforth–Moulton predictor–corrector method is used in two steps. First, the prediction step calculates a rough approximation of the desired quantity, typically employing an explicit method. Second, the corrector step refines the initial approximation recruiting another means, typically an implicit method. For more details, see [46].

Monte Carlo sampling for back analysis

At this point, the formulation of SEIVR-QH network, the fractional form of the differential equations, and its solution are established. The problem at hand is to estimate the unknown weights of the network, namely , , , , , , , , , , , and , such that the proposed SEIVR-QH network best describes the observed data. To this end, a novel two-step optimization algorithm is established in this section using Monte Carlo-based back analysis to obtain the optimal weights when is assumed as unity [47–50]. A sensitivity analysis is then used in the next section to investigate the influence of fractional order in the regression accuracy. To implement the back-analysis approach, the parameters involved in the problem, i.e., weights of the network, are defined as random variables. This makes it possible to consider a range of variation for these parameters and evaluate the predictions obtained by their various combinations. To better understand the parameters’ combination, suppose the parameters are placed in a lattice, in which the x-axis and y-axis are the parameters within the arranged set of ranges, then the variety of these parameters with different values is supposed as a random walk on this lattice. The range of variations defined for each random variable is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Random variables and their corresponding ranges of variation

| No. | Parameter | Distribution function | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uniform | 0.0 | 10.0 | |

| 2 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 3 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.05 | |

| 4 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 5 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 6 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 7 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 8 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 9 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| 10 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| 11 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| 12 | Uniform | 0.0 | 0.1 |

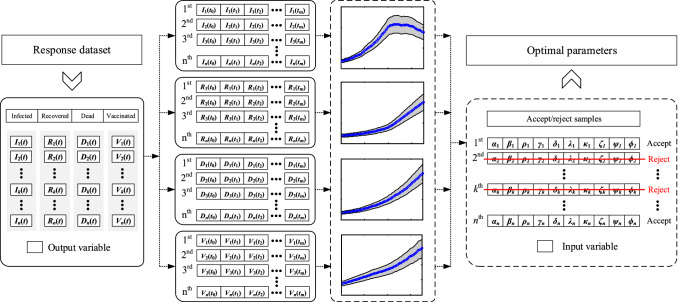

Next, 10,000 realizations are generated for each random variable. This process takes 30 min on a PC equipped with a 64 GB of random access memory (RAM) and an Intel Core i7-5820K central processing unit (CPU). Then, by introducing each set of realizations into the system of differential equations, a new SEIVR-QH problem is established that is solved using the method describe previously. This leads to 10,000 distinct predictions of the spread of the disease over time. The resulting database of I, R, D, and V is then used as the input of the back-analysis algorithm in the next step. The process described for implementing the Monte Carlo sampling is schematically shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Steps of using Monte Carlo sampling in combination with the SEIVR-QH network

To implement the back-analysis method, the actual observations of COVID-19, i.e., I, R, and D in Thailand, are compiled from the World Health Organization (WHO) online database [12]. In addition, the number of daily vaccinations is obtained from the Johns Hopkins University database [51]. The whole dataset is available on “Mendeley Data” [52]. The results are plotted in Fig. 3 from 2021-02-28 to 2021-08-30. This figure also demonstrates intervals of above and below the observed data. This is here considered as an allowable interval, and used as a filter to select the closest cases to the observed data among the 10,000 realizations of I, R, D, and V. This means that the allowable area is defined by a sample-selection criterion that leads the algorithm towards finding the best available fit. The process described for the selection/rejection of samples is schematically shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

The allowable interval defined above and below the observed data for a infected, b recovered, c dead, and d vaccinated cases

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram of the proposed back-analysis method

By applying the proposed filter to the data, 40 out of 10,000 samples fall within the allowable interval. Next, a new criterion is defined for a second-round selection to find the best sample from the previously selected 40 samples. For this purpose, the root mean square error (RMSE) between the predicted time series of I, R, D, and V in each sample and the observed time series is calculated for each of the 40 samples, as follows:

| 30 |

| 31 |

| 32 |

| 33 |

where , , , and are the RMSE of the sample for the infected, recovered, dead, and vaccinated, respectively; I(t), R(t), D(t) and V(t) are the actual measurements of infected, recovered, dead, and vaccinated cases, respectively; and , , , and are the time series of infected, recovered, dead, and vaccinated cases for the sample, respectively, computed using the proposed SEIVR-QH model. The results for , , , and are shown in columns 2–5 and 8–11 of Table 2. Next, by combining the RMSEs of I, R, D, and V using a square root of the sum of squares, the final selection criterion, denoted by , is defined:

| 34 |

The results of are shown in columns 6 and 12 of Table 2. The previously selected 40 samples are then sorted according to and the sample corresponding to the lowest , i.e., sample 4 in Table 2, is selected as the best fit. The optimal values of the parameters correspond to this sample are reported in Table 3. The time series of I, R, D, and V corresponding to the optimal parameters are also shown in Fig. 5.

Table 2.

RMSE for 40 samples

| No. | () | () | () | () | () | No. | () | () | () | () | () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.96 | 2.05 | 4.69 | 3.09 | 4.69 | 21 | 9.45 | 1.87 | 4.35 | 2.86 | 4.35 |

| 2 | 5.07 | 2.26 | 4.63 | 2.90 | 4.63 | 22 | 3.09 | 2.38 | 4.60 | 3.49 | 4.60 |

| 3 | 10.30 | 2.31 | 4.39 | 2.77 | 4.40 | 23 | 8.36 | 2.47 | 3.85 | 3.25 | 3.85 |

| 4 | 2.50 | 1.83 | 3.52 | 1.39 | 3.52 | 24 | 5.60 | 2.44 | 4.16 | 3.50 | 4.16 |

| 5 | 5.15 | 2.02 | 4.25 | 3.20 | 4.25 | 25 | 10.70 | 2.26 | 4.44 | 2.74 | 4.45 |

| 6 | 5.19 | 1.99 | 4.65 | 2.84 | 4.65 | 26 | 8.33 | 2.08 | 4.59 | 2.36 | 4.59 |

| 7 | 6.77 | 2.45 | 4.55 | 2.03 | 4.55 | 27 | 2.51 | 2.38 | 4.07 | 3.28 | 4.07 |

| 8 | 4.11 | 2.42 | 4.58 | 2.70 | 4.58 | 28 | 3.86 | 2.51 | 4.17 | 2.28 | 4.17 |

| 9 | 4.79 | 2.00 | 4.44 | 3.22 | 4.44 | 29 | 7.62 | 2.52 | 4.09 | 3.10 | 4.09 |

| 10 | 7.83 | 2.44 | 3.83 | 2.47 | 3.83 | 30 | 9.81 | 2.29 | 4.54 | 2.53 | 4.54 |

| 11 | 4.27 | 2.45 | 4.23 | 2.94 | 4.23 | 31 | 6.65 | 2.31 | 4.67 | 1.95 | 4.67 |

| 12 | 10.00 | 2.15 | 4.44 | 2.64 | 4.44 | 32 | 7.08 | 2.53 | 4.17 | 1.82 | 4.17 |

| 13 | 8.13 | 2.02 | 4.66 | 2.36 | 4.66 | 33 | 7.84 | 2.52 | 4.18 | 1.95 | 4.18 |

| 14 | 2.53 | 2.34 | 4.45 | 2.79 | 4.45 | 34 | 3.48 | 2.46 | 4.22 | 2.59 | 4.22 |

| 15 | 4.17 | 2.39 | 4.38 | 2.42 | 4.38 | 35 | 6.65 | 2.35 | 3.90 | 3.44 | 3.90 |

| 16 | 9.64 | 2.07 | 4.52 | 3.19 | 4.52 | 36 | 4.50 | 2.25 | 4.56 | 3.06 | 4.56 |

| 17 | 5.36 | 2.28 | 4.61 | 3.08 | 4.61 | 37 | 9.45 | 2.33 | 4.48 | 3.47 | 4.48 |

| 18 | 5.41 | 2.11 | 4.46 | 1.69 | 4.46 | 38 | 9.44 | 2.06 | 4.73 | 2.63 | 4.73 |

| 19 | 7.52 | 2.38 | 4.61 | 3.34 | 4.61 | 39 | 10.00 | 2.42 | 4.62 | 3.03 | 4.62 |

| 20 | 4.36 | 2.31 | 4.17 | 3.19 | 4.17 | 40 | 5.81 | 2.13 | 4.54 | 1.93 | 4.54 |

Table 3.

The optimal values of parameters

| No. | Parameter | Value | No. | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.1769 | 7 | 0.0360 | ||

| 2 | 0.1599 | 8 | 0.1239 | ||

| 3 | 0.0294 | 9 | 0.0061 | ||

| 4 | 0.3246 | 10 | 0.0837 | ||

| 5 | 0.1773 | 11 | 0.0010 | ||

| 6 | 0.3034 | 12 | 0.0015 |

Fig. 5.

Model predictions corresponding to the optimal parameters

Sensitivity analysis

As described in Sect. 2, the fractional form of the SEIVR-QH model, i.e., , provides a new degree of freedom to the compartmental system and provides the algorithm with further flexibility compared to the conventional differential equations of the first order, i.e., . This subsequently enables the system to better fit the actual data. Since the back analysis presented in this paper is implemented by four objective functions that must be optimized simultaneously to ensure that the number of infected, recovered, dead, and vaccinated cases matches the actual data, this flexibility is key in achieving accurate results. To make use of the fractional differential equation system to fit the SEIVR-QH network to the collected data of COVID-19 in this paper, the order of the equations is defined as a decision variable that assumes values less than unity. Thereafter, the new fractional problem is solved and the resulting fit is assessed for improvement in the prediction accuracy. To make use of the fractional differential equation system to fit the SEIVR-QH network to the collected data of COVID-19, the order of the equations is defined as a decision variable that assumes values less than unity. Then, the new fractional problem is solved and the resulting fit is assessed for improvement in the prediction accuracy.

For this purpose, assuming the optimal parameters obtained in Sect. 3, 11 different values of the decision variable that represent the fractional order are considered, including 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, 0.65, 0.7, 0.75, 0.8, 0.85, 0.9, 0.95 and 1. Next, a fractional form of SEIVR-QH problem is defined corresponding to each and analyzed separately by the method presented in Sect. 2. The results of each case are then stored in the form of time series I, R, and D. Table 4 shows the , , and , as well as for different values of . In addition, the corresponding time series of I, R, and D are plotted against different in Fig. 6.

Table 4.

RMSE values for different

| No. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.50 | 4.20 | 2.16 | 4.07 | 1.90 | 4.07 |

| 2 | 0.55 | 5.29 | 2.29 | 3.89 | 2.19 | 3.89 |

| 3 | 0.60 | 5.55 | 2.12 | 3.54 | 1.77 | 3.54 |

| 4 | 0.65 | 2.96 | 2.12 | 3.59 | 1.41 | 3.59 |

| 5 | 0.70 | 3.14 | 2.26 | 3.87 | 2.19 | 3.87 |

| 6 | 0.75 | 5.72 | 2.21 | 4.10 | 2.00 | 4.10 |

| 7 | 0.80 | 4.49 | 2.22 | 4.20 | 2.22 | 4.20 |

| 8 | 0.85 | 3.39 | 2.27 | 3.43 | 2.03 | 3.43 |

| 9 | 0.90 | 2.12 | 1.81 | 2.58 | 1.15 | 2.58 |

| 10 | 0.95 | 4.74 | 2.21 | 3.37 | 1.90 | 3.37 |

| 11 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 1.83 | 3.52 | 1.39 | 3.52 |

Fig. 6.

The resulting fit on the data for different

As seen, the best result is obtained for . In other words, assuming , a better fit to data is obtained and is minimized. Compared to the assumption of , the value of has changed from to , i.e., a reduction of 27% in the error measured. According to the new results, the number of infected, recovered, and dead at the beginning of 2022 in the Thailand will, respectively, reach about 4300, and 36,000. In addition, by November 2022, the number of infected will fall below 1500, indicating that the disease will be under control in the Thailand. It is noteworthy that these results are based on the fit obtained by the fractional model, which is more accurate and reliable than the results reported in Sect. 3.

Conclusion

In this paper, a compartmental network is established using fractional SEIVR-QH to predict the spread profile of COVID-19 in Thailand. To this end, the proposed network is employed in a Monte Carlo-based back analysis in which network weights, including , , , , , , , , , , , and , are defined as random variables. By generating a set of random samples for each random variable, the Monte Carlo-back analysis is used to find realizations of parameters whose predictions fall within a desired interval around the observed data. Thereafter, the RMSE criterion is applied to the selected samples to find the best fit to the Thailand data. Finally, a sensitivity analysis is conducted to investigate the effect of the order of the fractional operator on the accuracy of the fit. The primary results of this study are as follows:

Monte Carlo-back analysis identified 40 samples in close proximity of the observed data, having RMSE values between and . The best fit between them provides the optimal network weights as infection rate, , protection rate, , infectious to quarantine rate, , average latent time, , time-dependent recovery rate, and , time-dependent mortality rate, and , hospitalization rate, , vaccination rate, , hospitalization to recovery rate, , and hospitalization to mortality rate, .

The results of sensitivity analysis showed that the accuracy of data fitting is greatly improved by changing the fractional order, so that the of the best fractional fit, i.e., , reaches about , while that for the ordinary case, i.e., , is bound to . This means that the fractional form of the SEIVR-QH network improves the accuracy by about 27%.

The optimal output of the fractional SEIVR-QH network showed that by the end of 2021, the number of people infected (active), recovered and dead in Thailand will reach 4300, and 36,000, respectively.

The resulting number of infected cases also shows that the number of active cases fall below 1500 by November 2022, indicating that the disease will be under control in Thailand.

Although the compartmental networks benefit from simple configuration and straightforward implementation, they suffer from a common problem; that is, if compartments and computational nodes are added, their complexity is greatly increased, making it difficult to optimize the network to adapt to the data. The method proposed in this paper, however, enables the compartmental network to be expanded to the required size without concerning the complexity of the network and the size of the differential equation system. In other words, one can simply add the required nodes, such as reinfection after recovery and vaccine side effects, and then use Monte Carlo sampling method to optimize the network. This will be studied by authors in the future. Moreover, SEIVR-QH parameters are assumed as variables in the back analysis and incorporated in matching of the time histories. However, in addition to the model parameters, the fractional order of the differential equations is also defined as random variables and employed in the formulation of the Monte Carlo sampling method. This allows for a higher flexibility to fit the model to the data and thus, increases the model accuracy. Secondly, the probabilistic characteristics of the order of the differential equation, namely the mean and the standard deviation, are obtained from the optimal results of the first stage of the back analysis. This research is a practical step in defining the randomized fractional problem in solving the differential equations of disease spread. This is the subject of ongoing research by the authors on modeling the spread of COVID-19.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Authors’ comment: All data used in this paper are uploaded in Mendeley Data and are accessible via [51].]

Contributor Information

Arash Sioofy Khoojine, Email: arashsioofy@yibinu.edu.cn.

Mojtaba Mahsuli, Email: mahsuli@sharif.edu.

References

- 1.Cuddington K, Beisner BE. Ecological Paradigms Lost Routes of Theory Change. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz K, Heesterbeek J. Daniel Bernoulli’s epidemiological model revisited. Math. Biosci. 2002;180:1–21. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.J. Regan, J.P. Flynn, A. Rosenthal, H. Jordan, Y. Li, R. Chishti, F. Giguel, H. Corry, K. Coxen, J. Fajnzylber, E. Gillespie, D.R. Kuritzkes, N. Hacohen, M.B. Goldberg, M.R. Filbin, X.G. Yu, L. Baden, R.M. Ribeiro, A.S. Perelson, J.M. Conway, J.Z. Li, Viral load kinetics of SARS-COV-2 in hospitalized individuals with Covid-19, Open Forum Infectious Diseases ofab153 (2021). 10.1093/ofid/ofab153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Nogueira PJ, de Araujo Nobre M, Costa A, Ribeiro RM, Furtado C, Nicolau LB, Camarinha C, Luis M, Abrantes R, Carneiro AV. The role of health preconditions on Covid-19 deaths in Portugal: evidence from surveillance data of the first 20293 infection cases. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:2368. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odagaki T. Exact properties of SIQR model for COVID-19. Physica A. 2021;564:125564. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2020.125564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustamante-Castañeda F, Caputo J-G, Cruz-Pacheco G, Knippel A, Mouatamide F. Epidemic model on a network: analysis and applications to COVID-19. Physica A. 2021;564:125520. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2020.125520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassly NC, Fraser C. Mathematical models of infectious disease transmission. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:477–487. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado JAT, Ma J. Nonlinear dynamics of Covid-19 pandemic: modeling, control, and future perspectives. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;101:1525–1526. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05919-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quaranta G, Formica G, Machado JT, Lacarbonara W, Masri SF. Understanding Covid-19 nonlinear multi-scale dynamic spreading in Italy. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;101:1583–1619. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05902-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado JAT, Lopes AM. Rare and extreme events: the case of Covid-19 pandemic. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05680-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.L. Peng, W. Yang, D. Zhang, C. Zhuge, L. Hong, Epidemic analysis of Covid-19 in China by dynamical modeling. medRxiv (2020). 10.1101/2020.02.16.20023465

- 12.Worldometer, Worldometer Covid-19 data. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (2021)

- 13.Surano FV, Porfiri M, Rizzo A. Analysis of lockdown perception in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2021 doi: 10.1140/epjs/s11734-021-00265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamadou Y, Halidou A, Kapen PT. A review of mathematical modeling, artificial intelligence and datasets used in the study, prediction and management of COVID-19. Appl. Intell. 2020;50:3913–3925. doi: 10.1007/s10489-020-01770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SioofyKhoojine A, Shadabfar M, Hosseini VR, Kordestani H. Network autoregressive model for the prediction of Covid-19 considering the disease interaction in neighboring countries. Entropy. 2021 doi: 10.3390/e23101267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abou-Ismail A. Compartmental models of the Covid-19 pandemic for physicians and physician-scientists. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ndairou F, Area I, Nieto JJ, Torres DF. Mathematical modeling of Covid-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of Wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109846. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saha S, Samanta GP, Nieto JJ. Epidemic model of Covid-19 outbreak by inducing behavioural response in population. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;102:455–487. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05896-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarkar K, Khajanchi S, Nieto JJ. Modeling and forecasting the Covid-19 pandemic in India. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139:110049. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alanazi SA, Kamruzzaman MM, Alruwaili M, Alshammari N, Alqahtani SA, Karime A. Measuring and preventing Covid-19 using the sir model and machine learning in smart health care. J. Healthc. Eng. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8857346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguemdjo U, Meno F, Dongfack A, Ventelou B. Simulating the progression of the Covid-19 disease in Cameroon using sir models. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper I, Mondal A, Antonopoulos CG. A sir model assumption for the spread of Covid-19 in different communities. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139:110057. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. Shadabfar, M. Mahsuli, A. Sioofy Khoojine, V.R. Hosseini, Time-variant reliability-based prediction of COVID-19 spread using extended SEIVR model and Monte Carlo sampling. Results Phys. 26, 104364 (2021). 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Biswas MHA, Paiva LT, de Pinho M. A Seir model for control of infectious diseases with constraints. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2014;11:761–784. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2014.11.761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diaz P, Constantine P, Kalmbach K, Jones E, Pankavich S. A modified Seir model for the spread of Ebola in western Africa and metrics for resource allocation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018;324:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2017.11.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng S, Feng Z, Ling C, Chang C, Feng Z. Prediction of the Covid-19 epidemic trends based on Seir and AI models. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0245101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carcione JM, Santos JE, Bagaini C, Ba J. A simulation of a Covid-19 epidemic based on a deterministic Seir model. Front. Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mwalili S, Kimathi M, Ojiambo V, Gathungu D, Mbogo R. SEIR model for COVID-19 dynamics incorporating the environment and social distancing. BMC. Res. Notes. 2020;13:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-05192-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taghvaei A, Georgiou TT, Norton L, Tannenbaum A. Fractional sir epidemiological models. Sci. Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.28.20083865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Von Bertalanffy L. Quantitative laws in metabolism and growth. Q. Rev. Biol. 1957;32:217–231. doi: 10.1086/401873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerlee P. The model muddle: in search of tumor growth laws. Can. Res. 2013;73:2407–2411. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González-Parra G, Arenas AJ, Chen-Charpentier BM. A fractional order epidemicmodel for the simulation of outbreaks of influenza A(H1N1) Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2014;37:2218–2226. doi: 10.1002/mma.2968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demirci E, Ozalp N. A method for solving differential equations of fractional order. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2012;236:2754–2762. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2012.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinto CM, Carvalho AR. A latency fractional order model for HIV dynamics. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2017;312:240–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2016.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammad M, Trounev A, Cattani C. The dynamics of Covid-19 in the UAE based on fractional derivative modeling using Riesz wavelets simulation. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s13662-021-03262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh H, Srivastava H, Hammouch Z, Sooppy Nisar K. Numerical simulation and stability analysis for the fractional-order dynamics of Covid-19. Results Phys. 2021;20:103722. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boudaoui A, El hadj Moussa Y, Hammouch Z, Ullah S. A fractional-order model describing the dynamics of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) with nonsingular kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;146:110859. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.110859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ndairou F, Area I, Nieto JJ, Silva CJ, Torres DF. Fractional model of Covid-19 applied to Galicia, Spain and Portugal. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;144:110652. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.110652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babaei A, Ahmadi M, Jafari H, Liya A. A mathematical model to examine the effect of quarantine on the spread of coronavirus. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;142:110418. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.P. Sahoo, H.S. Mondal, Z. Hammouch, T. Abdeljawad, D. Mishra, M. Reza, On the necessity of proper quarantine without lock down for 2019-nCov in the absence of vaccine. Results Phys. 25, 104063 (2021). 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.He S, Peng Y, Sun K. SEIR modeling of the COVID-19 and its dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;101:1667–1680. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shadabfar M, Huang H. Simplified algorithm for reliability sensitivity analysis of structures: a spreadsheet implementation. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0213199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petras I. Fractional-Order Nonlinear Systems: Modeling, Analysis and Simulation. Berlin: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milici C, Draganescu G, Tenreiro Machado JA. Introduction to Fractional Differential Equations, 1. Berlin: Springer International Publishing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin W. Global existence theory and chaos control of fractional differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007;332:709–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2006.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.K. Diethelm, N.J. Ford, A.D. Freed, A predictor-corrector approach for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn 29, 3–22 (2002). 10.1023/A:1016592219341

- 47.ShadabFar M, Wang Y. Approximation of the Monte Carlo sampling method for reliability analysis of structures. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5726565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shadabfar M, Cheng L. Probabilistic approach for optimal portfolio selection using a hybrid Monte Carlo simulation and Markowitz model. Alex. Eng. J. 2020;59:3381–3393. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2020.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babaei A, Jafari H, Banihashemi S, Ahmadi M. Mathematical analysis of a stochastic model for spread of coronavirus. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;145:110788. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.110788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babaei A, Jafari H, Banihashemi S, Ahmadi M. A stochastic mathematical model for Covid-19 according to different age groups. Appl. Comput. Math. 2021;20:140–159. [Google Scholar]

- 51.J.H. University, John Hopkins university Covid-19 data. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ (2021)

- 52.A. Sioofy Khoojine, M. Shadabfar, M. Mahsuli, V.R. Hosseini, H. Kordestani, COVID-19 data of Thailand includes infected, recovered, dead, and vaccinated cases from 2021/02/28 to 2021/08/30. Mendeley Data. (2021). 10.17632/mnh7gc2mvz.1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Authors’ comment: All data used in this paper are uploaded in Mendeley Data and are accessible via [51].]