Abstract

The stability constants of lanthanide complexes with the potentially octadentate ligand CHXOCTAPA4–, which contains a rigid 1,2-diaminocyclohexane scaffold functionalized with two acetate and two picolinate pendant arms, reveal the formation of stable complexes [log KLaL = 17.82(1) and log KYbL = 19.65(1)]. Luminescence studies on the Eu3+ and Tb3+ analogues evidenced rather high emission quantum yields of 3.4 and 11%, respectively. The emission lifetimes recorded in H2O and D2O solutions indicate the presence of a water molecule coordinated to the metal ion. 1H nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion profiles and 17O NMR chemical shift and relaxation measurements point to a rather low water exchange rate of the coordinated water molecule (kex298 = 1.58 × 106 s–1) and relatively high relaxivities of 5.6 and 4.5 mM–1 s–1 at 20 MHz and 25 and 37 °C, respectively. Density functional theory calculations and analysis of the paramagnetic shifts induced by Yb3+ indicate that the complexes adopt an unprecedented cis geometry with the two picolinate groups situated on the same side of the coordination sphere. Dissociation kinetics experiments were conducted by investigating the exchange reactions of LuL occurring with Cu2+. The results confirmed the beneficial effect of the rigid cyclohexyl group on the inertness of the Lu3+ complex. Complex dissociation occurs following proton- and metal-assisted pathways. The latter is relatively efficient at neutral pH, thanks to the formation of a heterodinuclear hydroxo complex.

Short abstract

A non-macrocyclic ligand containing a rigid cyclohexyl spacer forms thermodynamically stable complexes with the lanthanide(III) ions in aqueous solution. The complexes also show remarkable kinetic inertness, though a structural change facilitates dissociation through the metal-assisted mechanism for the small lanthanides. The Gd(III) complex displays a relatively high relaxivity due to the presence of a water molecule coordinated to the metal ion, while the Eu(III) and Tb(III) analogues display strong metal-centered luminescence.

Introduction

Stable complexation of lanthanide ions (Ln3+) in aqueous solution is a coordination chemistry problem that has received much attention in the last 3 decades. This interest is related to a great extent to the important medical and biomedical properties of some lanthanide complexes, which include (1) the use of Gd3+ complexes as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),1−5 (2) the potential of luminescent Ln3+ complexes, particularly Eu3+ and Tb3+, in optical imaging and bioanalytical applications,6−8 and (3) the interesting properties of radioisotopes in the lanthanide series (i.e., 177Lu) for radiopharmaceutical applications.9,10 All these applications require stable complexation of metal ions and slow dissociation kinetics to avoid undesirable effects (toxicity issues).11,12 Furthermore, the application of Ln3+ complexes as radiopharmaceuticals requires a fast complexation of the radioisotope under mild conditions.13 Chelates for the preparation of efficient luminescent complexes must contain chromophore units suitable for indirect excitation of the relevant Ln3+ excited state, while protecting the metal ion from the vibrational quenching associated to the coordination of water molecules.14

The chelates used for stable Ln3+ complexes are often either macrocyclic or non-macrocyclic systems containing hard carboxylate or phosphonate donor groups whose denticity ranges from 7 to 10.15−17 Ligands with lower denticity like EDTA result in complexes endowed with low stability,18 while octa- or nonadentate ligands generally present favorable complexation properties.19,20 Macrocyclic ligands often form complexes with superior thermodynamic stability and exceptional kinetic inertness,21 but in some cases lead to very slow complexation kinetics.21−24 On the other hand, non-macrocyclic ligands such as DTPA5– (Chart 1) and DTPA bisamides often present faster dissociation kinetics, which is problematic for medical applications.11,25 Gd3+ complexes with DTPA bisamides were considered to have superior kinetic inertness than the DTPA5– analogue. However, more recent studies demonstrated that different anions present in vivo catalyze the dissociation of Gd3+ complexes with DTPA bisamides.11

Chart 1. Ligands Discussed in the Present Work.

In 2004, we reported the potentially octadentate ligand H4OCTAPA (Chart 1), whose Gd3+ complex was originally designed as a potential MRI contrast agent candidate.26 This study demonstrated the presence of a water molecule in the inner coordination sphere. Subsequent investigations performed by Mazzanti,27,28 Orvig,29,30 and our own group31 pointed to a high thermodynamic stability of the lanthanide complexes, which, however, exhibit fast dissociation kinetics. Orvig and co-workers showed that OCTAPA presents very promising properties for the development of 111In, 90Y, and 177Lu radiopharmaceuticals.32,33 Bifunctional derivatives of H4OCTAPA were also reported and successfully tested in vivo upon radiolabeling with these radioisotopes.34−36 The rigidified ligand CHXOCTAPA4– (also known as H4CDDADPA4–) was reported almost simultaneously by the group of Orvig and us.37,38 The corresponding Gd3+ complex is remarkably inert with respect to dissociation, with dissociation rate constants comparable to those of macrocyclic complexes such as [Gd(DO3A)].

In this paper, we present a detailed characterization of the Ln3+ complexes of CHXOCTAPA using a wide range of experimental and computational techniques. A multinuclear (1H and 13C) NMR study and density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to establish the structure of the complexes in solution, including the analysis of the paramagnetic Yb3+-induced 1H NMR shifts. These studies revealed unexpected features of the structure in solution of these complexes. We also present a full characterization of the relaxometric properties of the Gd3+ complex involving 1H nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion (NMRD) studies and 17O NMR chemical shifts and relaxation rates. A detailed analysis of the photophysical properties of the Eu3+ and Tb3+ complexes, including quantum yield determination, is reported. Finally, we also determined the stability of some of the complexes across the lanthanide series and assessed their kinetics of dissociation. The stabilities of the complexes formed with divalent metal ions of biological relevance are also reported.

Results and Discussion

Stability of the Ln3+ Complexes

Stability constant determination requires measuring the protonation constants of the ligand using the same electrolyte background. The protonation constants of CHXOCTAPA4– in 0.15 M NaCl reported previously by Orvig37 and us38 were in good agreement, though slight discrepancies can be noticed for log K5H and log K6 (Table S1, Supporting Information). These protonation processes take place in the pH range where complex dissociation occurs, and thus the accurate determination of their values is critical for determining stability constants. We therefore performed new potentiometric titrations using a higher ligand concentration (4.38 mM) in the pH range 1.65–11.95, which allows for a more accurate estimation of protonation constants (Figure S30, Supporting Information). These experiments yielded log K5H = 1.59(1) and log K6 = 0.61(4).

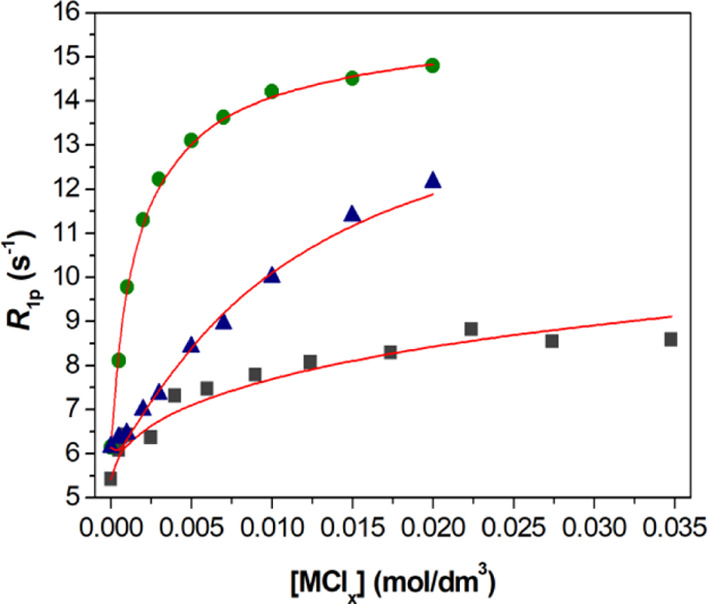

The stability of the Gd3+ complex with CHXOCTAPA4– was reported in a previous paper.38 This complex was found to be nearly fully formed at pH ∼ 2, which complicates stability constant determination using potentiometric titrations. The stability of the complex could be determined using the relaxometric method with aqueous solutions buffered with dimethylpiperazine (DMP).40 Relaxivity, r1p, refers to the paramagnetic longitudinal relaxation rate enhancement of water protons for a 1 mM concentration of the paramagnetic Gd3+ ion.41 The relaxivity of [Gd(H2O)8]3+ is considerably higher than that of the [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− complex, and thus complex dissociation provoked by the addition of competing metal ions (La3+, Yb3+, or Zn2+) causes an important increase of the relaxation rate of water protons (Figure 1). These experiments were carried out using the batch method and long equilibration times (4 weeks) to ensure that thermodynamic equilibrium was attained. The titration profiles observed for La3+ and Yb3+ are remarkably different, with addition of Yb3+ inducing a rather sharp inflection point. This anticipates that the stability of the Yb3+ complex is slightly higher than that of the La3+ analogue. The fit of the relaxation data confirms this qualitative analysis, yielding stability constants of log KYbL = 19.60(5) and log KLaL = 18.09(3).

Figure 1.

Relaxometric titrations (25 °C, 0.15 M NaCl) of the [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− complex with LaCl3 (squares, cLig = cGd3+ = 1.001 mM at pH = 4.69), YbCl3 (circles, cLig = cGd3+ = 1.113 mM at pH = 4.79), and ZnCl2 (triangles, cLig = cGd3+ = 1.001 mM at pH = 4.81). All solutions were buffered using 50 mM DMP. The solid lines show the fit of the data for stability constant determination.

The stability of the complexes with CHXOCTAPA4– experiences a slight increase from La3+ to Gd3+ as the charge density of the metal ion increases. This is the most common trend observed for Ln3+ complexes,42 though it is often more pronounced than observed here.19 Only a few cases of reversed stability were reported for the complexes of macrocyclic ligands.43−45 The complexes with Gd3+ and Yb3+ present very similar stability. The complexes with DTPA5– present a similar trend, with an initial increase in stability for the light lanthanide ions, the stability constants becoming nearly constant for the heaviest lanthanides (Table 1).20,46

Table 1. Protonation and Stability Constants of the Metal Complexes Formed with CHXOCTAPA4– and Related Ligands (25 °C, 0.15 M NaCl).

| CHXOCTAPA4– | OCTAPA4–a | DTPA5– | DO3A3–g | DOTA4– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log KLaL | 17.82(1); 18.09(3)k | 19.92 | 19.49e | 18.63 | 21.7i |

| log KLaHL | 2.00(1) | 2.60e | |||

| log KLaH-1L | 12.75(4) | ||||

| log KGdL | 19.92(1) | 20.23 | 22.03d/22.46e | 21.56/19.06h | 24.7i |

| log KGdHL | 1.02(4) | 1.96d/2.39e | |||

| log KGdH-1L | 12.45(2) | ||||

| log KYbL | 19.65(1), 19.60(5)k | 19.90b | |||

| log KYbHL | 1.89(2) | ||||

| log KYbH-1L | 12.24(2) | ||||

| log KLuL | 20.49/20.08c | 22.44e | 21.44 | 25.4i | |

| log KLuHL | 2.18e | ||||

| log KMgL | 5.96(1) | 6.12 | 9.27e | 11.64 | 11.49g |

| log KMgHL | 6.03(3) | 5.24 | 6.85e | ||

| log KMgH2L | 4.54 | ||||

| log KCaL | 8.42(2) | 9.55/9.4 | 10.7f | 12.57 | 16.11g |

| log KCaHL | 4.83(5) | 3.92 | 6.11f | 4.60 | |

| log KCaH2L | 4.57(6) | 2.56 | |||

| log KCa2L | 3.88(7) | 1.55 | |||

| log KZnL | 16.97(3) | 18.91 | 17.58d | 21.57 | 20.21g |

| log KZnHL | 4.04(3) | 3.91 | 5.37d | 3.47 | |

| log KZnH2L | 3.15(2) | 3.54 | 2.38d | 2.07 | |

| log KZnH3L | 1.34(4) | ||||

| log KZnH-1L | 11.63(7) | ||||

| log KZn2L | 3.99(5) | 2.3 | 4.33d | ||

| log KZn2HL | 3.26(4) | ||||

| log KZn2L(OH) | 7.63(4) | ||||

| log KZn2L(OH)2 | 8.39(2) | ||||

| log KCuL | 20.76(6)j | 22.08 | 23.40d | 25.75 | 24.83g |

| log KCuHL | 4.02(9)j | 3.95 | 4.63d | 3.65 | |

| log KCuH2L | 4.07(2)j | 3.21 | 2.67d | 1.69 | |

| log KCuH3L | 2.03d | ||||

| log KCuH-1L | 12.26(5)j | ||||

| log KCu2L | 5.64(6)j | 3.2 | 6.56d | ||

| log KCu2HL | 3.33(6)j | 2.20d | |||

| log KCu2L(OH) | 7.80(11)j | ||||

| log KCu2L(OH)2 | 9.10(11)j |

Data from ref (31) in 0.15 M NaCl unless otherwise indicated.

Data in 0.16 M NaCl from ref (29).

Data from ref (34).

Data in 0.15 M NaCl from ref (20).

Data in 0.1 M KCl from ref (46).

Data in 0.1 M NaCl from ref (46).

Data in 0.1 M KCl from ref (48) unless otherwise stated.

Data in 0.15 M NaCl from ref (49).

Data in 0.1 M NaCl from ref (50).

Data obtained by simultaneous fitting of UV–vis and pH-potentiometry titration data obtained at 1:1 and 2:1 metal-to-ligand ratio.

Determined using relaxometric titrations.

The stability constants determined for the Ln3+ complexes of CHXOCTAPA4– by different methods (pH-potentiometry and 1H-relaxometry) are in excellent agreement, being comparable with those reported for the analogues with OCTAPA4– (Table 1).29,31 This indicates that the replacement of the ethylenediamine spacer by a more rigid cyclohexyl group does not have a significant impact on complex stability, as observed recently for uranyl complexes.47 The stability constants characterizing the Ln3+ complexes of CHXOCTAPA4– are similar to those of DO3A3–,48,49 but remain lower than those reported for the analogous DOTA4– complexes.48,50 We note that the stability constants determined in 0.1 M KCl and 0.15 M NaCl for the Gd3+ complex of DTPA5– are in good agreement, while there is a significant difference in the case of DO3A3–. This shows that Na+ cations form a relatively stable complex with DO3A3– derivatives.49

Potentiometric titrations using a high ligand concentration (4.38 mM) in the presence of equimolar concentrations of La3+, Gd3+, and Yb3+ allowed for determining stability and protonation constants of the metal complexes. The log KLnL values obtained for the La3+ and Yb3+ complexes are in excellent agreement with those obtained by relaxometry. These experiments afforded also the protonation constant of the complexes and also evidenced the formation of hydroxo complexes at high pH (log KLnH-1L > 12, Figures S7 and S8). For Gd3+, the stability constant determined by potentiometry log KGdL = 19.92(1) is slightly lower than that obtained previously by relaxometry (log KGdL = 20.68).38 This slight discrepancy is related to the different set of ligand protonation constants used in the analysis.

The stability constants of the Mg2+ and Ca2+ complexes of CHXOCTAPA4– could be determined using direct potentiometric titrations. Both cations form different protonated complex species in solution. Similarly, potentiometric titrations, using both 1:1 and 1:2 (M/L) stoichiometric ratios, allowed for determining the protonation constants of the complexes formed with Zn2+ and Cu2+. These metal ions also form relatively stable dinuclear complexes characterized by the corresponding equilibrium constants KM2L and different hydroxo complexes at basic pH, yielding rather complex species distributions in solution (Table 1; see also Figures S1–S8, Supporting Information).

The stability constant of the Zn2+ and Cu2+ complexes is too high to be determined using direct pH potentiometric titrations, and thus UV–vis spectrophotometric experiments were carried out under acidic pH to determine the stability of the Cu2+ complex, following the changes of the d–d absorption band at ca. 710 nm with pH (Figure S9, Supporting Information). The stability of the Zn2+ complex was obtained by competition titration with Gd3+ using relaxometry. The log KML values characterizing the formation of the Ca2+, Zn2+ and Cu2+ complexes with CHXOCTAPA4– are 1–2 log K units lower than those of the corresponding complexes formed with OCTAPA4–. This is in contrast to previous studies, which evidenced a gain in complex stability with small metal ions upon incorporation of rigid cyclohexyl groups.56 This imparts CHXOCTAPA4– with a higher selectivity for the Ln3+ ions than OCTAPA4– over potentially competing divalent metal ions in vivo.

Photophysical Properties

Ligands containing picolinate moieties were found to act as rather efficient sensitizers of the luminescent emission of Eu3+ and particularly Tb3+.57−60 Furthermore, picolinate units can be easily functionalized to tune their photophysical properties and provide efficient two-photon absorption.61−63 Thus, we have investigated the emission spectra of the [Ln(CHXOCTAPA)]− (Ln = Eu, Tb) complexes in aqueous solution. The emission spectrum of the Eu3+ complex is dominated by the 5D0 → 7F2 (ΔJ = 2) transition and presents a rather intense 5D0 → 7F0 transition (Figure 2). This spectral pattern is typical of Eu3+ in a coordination environment with a low symmetry.64 The lifetime of the excited 5D0 state measured in H2O solution (598 μs) is typical of Eu3+ complexes containing one coordinated water molecule (q = 1). Lifetime measurements recorded in D2O solutions afford a much longer lifetime of 2363 μs, as would be expected considering the efficient vibrational quenching of Eu3+ luminescence provoked by O–H oscillators of coordinated water molecules.51 The use of the empirical relationship proposed by Horrocks gives a q value of 1.0 ± 0.1, confirming the presence of a water molecule coordinated to the metal center (Table 2).51

Figure 2.

Emission spectra of the Eu3+ complexes with CHXOCTAPA4– (blue solid line) and OCTAPA4– (green dashed line) recorded in H2O solution at pH 7.1 (λex = 279 nm; absorption and emission slits 1 nm, 10–4 M).

Table 2. Spectroscopic Properties of [Ln(CHXOCTAPA)]− and [Ln(OCTAPA)]− Complexes Measured in Aqueous Solutions (pH 7.1)c.

The emission spectrum recorded for the Tb3+ complex presents the 5D4 → 7FJ transitions expected for this metal ion, with J ranging from 6 to 3 (Figure S11, Supporting Information). The emission lifetimes of the excited 5D4 state recorded in H2O and D2O provide a q value of 1.3,52 in agreement with the results obtained for Eu3+.

The emission quantum yields measured for the Eu3+ (3.4%) and Tb3+ (11%) complexes were obtained using the corresponding trispicolinate complexes as secondary standards53,54 and are within the normal range reported for monohydrated chelates containing picolinate units.57,65,66 Thus, it is surprising that quantum yields one order of magnitude lower were reported by Platas-Iglesias et al. for the OCTAPA4– analogues using quinine sulfate as standard (0.3 and 1.9% for Eu3+ and Tb3+ respectively).26 Furthermore, higher quantum yields for the latter complexes were presented in a PhD thesis,67 suggesting that the values reported by Platas-Iglesias were incorrect. We therefore reexamined the photophysical properties of the complexes with OCTAPA4– (Table 2). These studies confirmed that the emission quantum yields of the Eu3+ and Tb3+ complexes with CHXOCTAPA4– and OCTAPA4– are very similar. The emission lifetimes measured for the two families of complexes are also very close, confirming the formation of q = 1 species in solution. The emission spectra recorded for the two Eu3+ complexes are rather similar, with a comparable splitting of the magnetic dipole 5D0 → 7F1 transition (∼140 cm–1). We notice that the hypersensitive ΔJ = 2 transition is more intense in OCTAPA4– than in CHXOCTAPA4–, while the intensity of the magnetic dipole ΔJ = 1 transition remains very similar (Figure 2). This results in ΔJ = 2/ΔJ = 1 intensity ratios of 2.6 and 2.9 for the complexes with CHXOCTAPA4– and OCTAPA4–, respectively. It has been shown that the relative intensity of these transitions is very sensitive to changes in the metal coordination environment.68,69 Because the nature of the donor atoms and the number of coordinated water molecules is identical in the two complexes, these results suggest that the two complexes are characterized by somewhat different coordination polyhedra.

Further insights into the sensitization efficiency of Eu3+ by the picolinate chromophores can be gathered by applying the methodology developed by Werts,55 which allows for estimating the radiative lifetime of the Eu3+-centered emission τRad, the metal-centered emission quantum yield ΦEu and the efficiency of the sensitization process ηsen (Table 2). The results of this analysis show that the observed emission quantum yields are limited by rather low ΦEu values associated to the quenching effect of the coordinated water molecule and a modest sensitization efficiency.70−72

Structure of the Ln3+ Complexes in Solution

The structure of the [Ln(CHXOCTAPA)]− complexes was investigated in D2O solutions at pH 7.0 using 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. We initiated the study by examining the NMR spectra of the diamagnetic La3+ and Lu3+ complexes. The spectra of the Lu3+ complex are consistent with the presence of a main isomer in solution and a C1 symmetry, as it shows 24 proton resonances and the same number of carbon signals (Figure S20, Supporting Information). A full attribution of the NMR data was attained with the aid of 2D COSY, HSQC, and HMBC experiments (Table S2, Supporting Information). The spectrum points to a rigid structure of the complex in solution, as the 1H spectrum displays well-resolved AB spin systems for the methylene protons. The spectra of the La3+ complex are, however, more complicated, evidencing the presence of two isomers in solution with very similar populations.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the paramagnetic Ce3+ complex presents paramagnetically shifted signals in the approximate range 25 to −35 ppm (Figure 3). The spectrum is consistent with the presence of two isomers in solution, while only one isomer was observed previously for the Eu3+ complex.38 All together, these results indicate that the complexes of the large lanthanide ions (La–Ce) are present in solution in the form of two diastereoisomers, while only one isomer is observed for Eu3+ and the heavier Ln3+ ions. DFT calculations were performed to understand the nature of the two diastereoisomers present in solution for the [Ln(CHXOCTAPA)]− complexes. A careful exploration of the potential energy surface provided two minimum energy geometries with rather small energy differences (Figure 3). These two minimum energy structures differ in the arrangement of the picolinate and acetate groups. One of the structures is characterized by nearly linear angles defined by the two pyridyl N atoms and the metal ion (NPY–Ln–NPY, ∼170°) and has been denoted as the trans isomer. Conversely, the second isomer (cis) is characterized by the coordination of picolinate (and acetate) groups on the same side of the metal ions, resulting in NPY–Ln–NPY angles of ∼120°. The trans isomer is the most stable one at the beginning of the lanthanide series (La–Pr), while the cis isomer is predicted to be more stable for the second part of the lanthanide series (Gd–Lu). Analogous calculations performed for the [Ln(OCTAPA)]− complexes provide a similar trend for the relative energies, though the cis isomer is stabilized later on along the series. As a result, our calculations predict that the most stable form for the [Gd(OCTAPA)]− complex is the trans isomer, which is in nice agreement with the X-ray structure reported by Mazzanti.27 A trans structure was also established for the light Ln3+ complexes with OCTAPA4– by analysis of the paramagnetic 1H NMR shifts.26 The cis isomer is characterized by different configurations of the amine N atoms (S,R or R,S), while these N atoms have the same configuration in the trans isomer (S,S or R,R, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Top: Structures of the two isomers of [Gd(CHXOCTAPA) (H2O)]−·2H2O (second-sphere water molecules omitted for clarity) and relative energies calculated across the lanthanide series for the complexes with CHXOCTAPA4– and OCTAPA4–. Bottom: 1H NMR spectrum of the Ce3+ complex recorded in D2O solution (300 MHz, 25 °C, pH 7.0). Asterisks denote a minor species present in solution.

The 1H NMR spectra of Yb3+ complexes encode structural information that can be used to validate structural models obtained with DFT calculations.73 The 1H NMR signals due to ligand nuclei in paramagnetic Yb3+ complexes experience large frequency shifts induced by the pseudocontact mechanism (δPC), which is related to the anisotropy of the magnetic susceptibility associated to the 4f electrons.74,75 The pseudocontact shift can be expressed as in eq 1 when the reference frame coincides with the principal directions of the magnetic susceptibility tensor χ

| 1 |

where r2 = x2 + y2 + z2, x, y, and z are the Cartesian coordinates of a nucleus i relative to the location of a Yb3+ ion placed at the origin, and Δχax and Δχrh are the axial and rhombic parameters of the symmetric magnetic susceptibility tensor.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the Yb3+ complex of CHXOCTAPA is well resolved, presenting paramagnetically shifted resonances in the range +109 to −41 ppm (Figure 4). The spectrum was assigned on the basis of line-width analysis, as the paramagnetic contribution to the linewidths of 1H resonances depends on 1/r6.76 Thus, those protons located at shorter distances from the paramagnetic ion are characterized by broader resonances. Additional information for the assignment of the 1H NMR spectrum was gained from 1H,1H–COSY measurements, which show cross-peaks relating the protons of the pyridyl units, the geminal CH2 protons of the acetate and picolinate groups, and the protons of the cyclohexyl unit placed at a three-bond distance. The analysis of the paramagnetic shifts was accomplished by using eq 1, using the diamagnetic shifts observed for the Lu3+ analogue (Table S2, Supporting Information). Given the lack of any symmetry axis in the complex, the position of the magnetic axes cannot be anticipated. Thus, we performed a least squares fitting of the paramagnetic shifts to eq 1 by using five fitting parameters: The axial (Δχax/12π) and rhombic (Δχrh/8π) parts of the magnetic susceptibility tensor and three Euler angles relating the input orientation and that of the magnetic susceptibility tensor. The structure of the complex obtained with DFT calculations was used as a structural model.

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectrum of [Yb(CHXOCTAPA)]− (300 MHz, 25 °C, pH 7.0) and plot of the calculated chemical shifts versus those obtained with eq 1 and the structure of the cis isomer. The line represents the identity line.

The agreement of the chemical shifts observed for the Yb3+ complex and those calculated with eq 1 (and the estimates of the diamagnetic shifts using the Lu3+ complex) is excellent, with deviations <4.2 ppm and a mean deviation of 1.26 ppm (Figure 4, see also Table S2, Supporting Information). This is confirmed by the agreement factor AFj = 0.050, which is similar to or better than those reported previously and considered to be satisfactory (0.06–0.11).77−81 Lower agreement factors were also calculated for symmetrical systems, but in those cases, the fit of the data involved a low number of experimental chemical shifts.73 This analysis indicates that the structure of the cis isomer obtained with DFT represents a good approximation of the actual structure of the complex in solution. Conversely, an unacceptable fit was obtained by using the trans isomer as the structural model (AFj = 0.363), with deviations of the experimental and calculated data of up to ∼34 ppm. As would be expected, the magnetic susceptibility tensor determined for the fit of the data for the cis isomer is rhombic, with Δχax/12π = −2379 ± 29 ppm Å3 and Δχrh/8π = 919 ± 65 ppm Å3. The orientation of the magnetic axis is such that one of the picolinate lies close to the yz plane and one of the carboxylate groups on the xz plane (Figure S22, Supporting Information).

1H NMRD and 17O NMR Studies

The relaxivity of [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− was investigated in the proton Larmor frequency range 0.01–80 MHz, corresponding to magnetic field strengths varying between 2.34 × 10–4 and 1.88 T (Figure 5). The relaxivities recorded at 20 MHz (Table 3) are slightly higher than those reported for [Gd(OCTAPA)]−, [Gd(DOTA)]−, and [Gd(DTPA)]2–, but still consistent with the presence of a water molecule in the inner coordination sphere, as indicated by emission lifetime measurements (see above). As expected, fast rotation of the complex in solution limits proton relaxivity, which decreases with increasing temperature. Because the inner-sphere contribution to 1H relaxivity is affected by a relatively large number of parameters, we have also recorded reduced longitudinal (1/T1r) and transverse (1/T2r) 17O NMR relaxation rates and reduced chemical shifts (Δωr) of an aqueous solution of the complex (19.9 mM, pH = 7.27). These studies provide independent information about some important parameters that control 1H relaxivity, especially the exchange rate of the coordinated water molecule(s) (kex298) and the rotational correlation time (τR298).82 The 1/T2r values increase with decreasing temperature at high temperatures, reach a maximum at ca. 322 K, and then decrease. This is typical of systems that experience a changeover from a slow exchange regime at low temperature to a fast exchange condition at high temperature.83 The inflection point observed for the 1/T2r values is also clearly visible in the chemical shift data.

Figure 5.

Top: 1H NMRD profiles recorded at different temperatures for [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− (pH 7.27). Bottom: Reduced transverse (green ■) and longitudinal (red ▲) 17O NMR relaxation rates and 17O NMR chemical shifts (blue ●) measured for [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− at 9.4 T (0.0199 mM, pH = 7.27). The lines represent the fit of the data as explained in the text.

Table 3. Parameters Obtained from the Simultaneous Analysis of 17O NMR and 1H NMRD Data.

| CHXOCTAPA4– | OCTAPA4–b | DTPA5–c | DOTA4–c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r1p at 25/37 °C, 20 MHz/mM–1 s–1 | 5.6/4.5 | 5.0/3.9 | 4.7/4.0 | 4.7/3.8 |

| kex298/106 s–1 | 1.58 ± 0.09 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| ΔH⧧/kJ mol–1 | 54.6 ± 1.8 | 40.1 | 51.6 | 49.8 |

| τRH298/ps | 75 ± 3 | 55b | 58b | 77 |

| Er/kJ mol–1 | 19.5 ± 1.2 | 17.9 | 17.3 | 16.1 |

| τv298/ps | 11.3 ± 0.06 | 12.6 | 25 | 11 |

| Ev/kJ mol–1 | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.6 | 1.0a |

| Δ2/1020 s–2 | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 1.2 | 0.46 | 0.16 |

| DGdH298/10–10 m2 s–1 | 20.0a | 19 | 20 | 22 |

| EDGdH/kJ mol–1 | 22a | 30.1 | 19.4 | 20.2 |

| A/ℏ/106 rad s–1 | –3.06 ± 0.08 | –2.31 | –3.8 | –3.7 |

| χ(1 + η2/3)1/2/MHz | 10.7a | 17b | 14b | 10 |

| rGdH/Å | 3.005a | 2.969a | 3.1a | 3.1a |

| rGdO/Å | 2.480a | 2.54a | 2.5a | 2.5a |

| aGdH/Å | 3.5a | 3.4a | 3.5a | 3.5a |

| q298 | 1a | 1a | 1a | 1a |

A simultaneous fitting of the 1H NMRD and 17O NMR data of [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− was performed using a well-established methodology that treats the inner-sphere contribution to relaxivity with the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan theory84−86 and the outer-sphere mechanism with the translational diffusion model proposed by Freed.87 The 17O NMR data were fitted with the standard Swift–Connick88,89 equations. Several parameters have been fixed during the fitting procedure: the number of water molecules coordinated to the Gd3+ ion was fixed to q = 1 on the basis of the luminescence lifetime measurements described above, the distance of closest approach for the outer-sphere contribution aGdH was fixed at 3.5 Å, and the distances between the Gd3+ ion and the H and O atoms of the coordinated water molecule (rGdH and rGdO) were set to the values obtained from DFT calculations. The value of the 17O quadrupole coupling constant χ(1 + η2/3)1/2 was also estimated using DFT calculations. In previous studies, the quadrupole coupling constant was allowed to vary during the fitting procedure,90 providing fitted values that deviated markedly from that obtained for acidified water (7.58 MHz).91 As a result, the fits of the data gave low rotational correlation times τR (Table 3). However, it has been demonstrated that coordination to Gd3+ provokes negligible changes in the quadrupole constant.92 Our calculations provided χ = 7.77 MHz and an asymmetry parameter η = 0.84 (χ = 6.68 MHz and η = 0.93 for pure water), yielding a χ(1 + η2/3)1/2 value of 10.7 MHz. Additional parameters that were fixed to reasonable values were the diffusion coefficient DGdH298 (20 × 10–10 m2 s–1), its activation energy EDGdH (22 kJ mol–1), and the activation energy for the modulation of the zero field splitting interaction (Ev = 1 kJ mol–1). The rotational correlation time τR affects both the T117O relaxation rates and r1p values. However, it has been shown that rotational correlation time characterizing the Ln–Hwater vector is ∼65% shorter than that of the Ln–Owater vector.93 Thus, we included in the fitting two different τR values with the constraint that τRH/τRO = 0.65.

An excellent fit of the 17O NMR and 1H NMRD data was obtained using the parameters listed in Table 3. The water exchange rate kex298 is lower than those determined for the complexes with OCTAPA4– and DTPA5–. A faster average exchange rate was also determined for the complexes with DOTA4–, though in the latter case two isomers with very different water exchange parameters are present in solution.94 The rigidity of the CHXOCTAPA4– ligand likely increases the energy cost required to reach the transition state responsible for the water exchange process, resulting in a rather low water exchange rate.95 A similar effect was observed previously upon rigidification of OCTAPA derivatives incorporating phosphonate groups.96 The parameters characterizing the relaxation of the electron spin are very similar to those obtained for OCTAPA4–, as would be expected from the similar relaxivities observed at low magnetic fields (<1 MHz). Complexes with DOTA4– derivatives display slower electron spin relaxation, as a result of lower squared zero field splitting energies (Δ2, Table 3). Finally, the value obtained for the hyperfine coupling constant A/ℏ is in excellent agreement with that estimated with DFT (3.10 × 106 rad s–1), which provides support to the reliability of the analysis.

Dissociation Kinetics

The slow dissociation of Ln3+ complexes is a key property for their application as both MRI contrast agents and radiopharmaceuticals. In the case of MRI contrast agents, there is an increasing concern on potential toxicity issues related to the release of Gd3+ in vivo.97 Radiopharmaceuticals are injected in low doses, and thus chemical toxicity problems are likely not an important concern. However, complex dissociation may have negative effects by reducing the amount of radioisotope that reaches the desired target, thereby exposing to radiation healthy tissue.98 In a previous paper, we analyzed the dissociation kinetics of the Gd3+ complex, which was found to be remarkably inert.38 Herein, we present a detailed analysis of the dissociation kinetics of the Lu3+ analogue, given the potential of 177Lu for therapeutic applications. We have shown recently that the dissociation kinetics of Ln3+ complexes may vary by several orders of magnitude across the lanthanide series, and thus the remarkable inertness of the Gd3+ complex does not necessarily ensure that the Lu3+ analogue behaves in a similar way.99

The dissociation of the Lu3+ complex with CHXOCTAPA4– was investigated by following the rates of exchange reactions taking place with Cu2+ at different proton concentrations (pH 3.30–4.72). The reactions were monitored in the presence of at least 10-fold Cu2+ excess to ensure pseudo first-order conditions. The observed rate constants display a rather unusual behavior, as increasing cH+ provokes a slight initial decrease of the dissociation rates, which subsequently increase at higher cH+ values. Furthermore, Cu2+ is also affecting significantly the complex dissociation rates (Figure 6). This indicates that the Lu3+ complex experiences dissociation by following the proton-assisted and metal-assisted pathways, the latter involving formation of a hetero-dinuclear complex. The dinuclear complex appears to form a hydroxo complex at relatively low pH that is responsible for the increase in kobs values in the low proton concentration side (Figure 6). Thus, the dissociation of the complex can be expressed as in eq 2, where k0 is the rate constant characterizing the spontaneous dissociation, kH is the rate constant characterizing the proton-assisted dissociation, and kCu and kCuOH are associated with the metal-assisted dissociation pathways, the latter with the formation of a hydroxo dinuclear complex.

| 2 |

Figure 6.

Plot of the pseudo-first-order rate constants measured for the [Lu(CHXOCTAPA)]− as a function of H+ ion concentration (50 mM DMP, 25 °C, 0.15 M NaCl) using different metal ion excess [10× (5.53 mM), 20× (11.07 mM), 30× (16.60 mM), and 40× (22.14 mM) was applied with pH = 3.30, 3.50, 3.80, 4.17, and 4.49]. The solid lines represent the fits of the data to eq 7.

Considering that the total concentration of complexed Lu3+ is given by eq 3 and the equilibrium constants defined by eqs 4–6, the rate constants can be expressed as in eq 7, where k1 = kH × KH, k3Cu = kCuKCu, and k6 = kCuOHKCu(OH)KCu.

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

Attempts to fit the data to eq 7 including k0 as fitting parameter provided a small negative value, which indicates that spontaneous dissociation does not play any role under the conditions used for kinetic experiments. Furthermore, it is difficult to estimate the rate constant characterizing the spontaneous reaction pathway within the same pH range where the dissociation of the Lu(L)Cu(OH) complex takes place, as the latter acts as a competitive dissociation path to the spontaneous dissociation. A similar situation occurred for KH, revealing that the KH[H+] term in the denominator of eq 7 has a negligible contribution to kobs. This is expected considering the low protonation constants determined using potentiometry (log KLnH in the range 1–2, Table 1) and the relatively low proton concentrations used for kinetic experiments (<10–6 M, Figure 6). The results of the fit are shown in Table 4, together with a comparison with the data reported previously for the Gd3+ complexes of CHXOCTAPA4–,38 OCTAPA4–,31 DTPA5–,25 and DO3A3–.48 It is worth mentioning that the dissociation pathway through formation of a hydroxo dinuclear species was not detected for the Gd3+ analogue, which was investigated in approximately the same pH range. The formation of hydroxo complexes is more likely to occur as the size of the lanthanide ion decreases across the series due to the lanthanide contraction, as indicated by the corresponding hydrolysis constants (log KLn(OH) = −7.83 and −7.27 for Gd3+ and Lu3+, respectively).100 Alternatively, the structural change occurring close to the center of the lanthanide series could be responsible for the different behavior of the Gd3+ and Lu3+ complexes.

Table 4. Rate and Equilibrium Constants Characterizing the Dissociation of the CHXOCTAPA4– Complexes and Related Systems (25 °C).

| [LuCHXOCTAPA]− | [GdCHXOCTAPA]−a | [GdOCTAPA]−b | [GdDTPA]2–c | [GdDO3A]d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1/M–1 s–1 | 3.74 ± 0.06 × 10–2 | 1.60 × 10–2 | 11.8 | 0.58 | 0.023 |

| k2/M–2 s–2 | 2.5 × 104 | 9.7 × 104 | |||

| k3Cu/M–1 s–1 | 6.3 ± 0.3 × 10–4 | 6.8 × 10–4 | 22.5 | 0.93 | |

| k6Cu/M–2 s–1 | 5.1 ± 0.3 × 105 | 5.0 × 109 | |||

| KH | 737 | 2.6 | 100 | ||

| KCu | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 48 | 13 | ||

| t1/2/he | 876 | 1.49 × 105 | 0.15 | 202 | 2.10 × 105 |

The rate constants shown in Table 4 indicate that the Gd3+ and Lu3+ analogues present similar inertness with respect to their dissociation following the proton-assisted and metal-assisted pathways, as judged by the values of the k1 and k3Cu rate constants. However, the metal-assisted pathway with the formation of a hydroxo complex, characterized by k6, plays an increasingly important role in the dissociation of the complex as the concentration of OH– increases. As a result, this pathway is mainly responsible for complex dissociation at pH 7.4, a situation that is clearly reflected in the half-lives of the complex calculated at pH 7.4 using [Cu2+] = 1 μM (Table 4). Nevertheless, the half-life estimated for [Lu(CHXOCTAPA)]− remains three times longer than that of [Gd(DTPA)]2–, but clearly shorter than that of the macrocyclic complex [Gd(DO3A)]. The effect that the rigid cyclohexyl unit has in improving kinetic inertness is also obvious when comparing the half-lives of CHXOCTAPA4– and OCTAPA4– derivatives.

Conclusions

The present contribution has shown that the octadentate CHXOCTAPA4– ligand forms fairly stable complexes with the Ln3+ ions, with stability constants in the range log KLnL ∼ 17.8–19.7. The presence of the rigid cyclohexyl ring causes a slight increase of the selectivity of the ligand for the Ln3+ ions over Cu2+ and Zn2+. The picolinate units are rather efficient in sensitizing the Eu3+ and particularly Tb3+ luminescence, with emission quantum yields comparable to those of the OCTAPA4– analogues. The complexes are monohydrated (q = 1) in solution, as indicated by emission lifetime measurements. The exchange rate of the water molecule coordinated to Gd3+ (as confirmed by 17O NMR studies) is rather low when compared with the OCTAPA4–, DTPA5–, and DOTA4– analogues, likely as a result of the rigid structure of the complex.

The coordination chemistry reported in this paper provided two unexpected results. First, the analysis of the structural information encoded by the pseudocontact shifts, induced by Yb3+, demonstrate that this complex presents an unusual cis structure in which the amine N atoms adopt S,R configurations. DFT calculations show that this conformation is stabilized across the lanthanide series over the trans R,R (or S,S) conformation. The presence of the cyclohexyl group causes a significant stabilization of the S,R conformation. A second unexpected effect was observed when investigating the dissociation of the Lu3+ complex in the presence of exchanging Cu2+ ions. Complex dissociation at physiological pH was found to occur mainly through the metal-assisted mechanism that involves the formation of a hydroxo complex, a pathway that was not observed previously for the Gd3+ analogue. We hypothesize that this pathway may be relevant for the dissociation of complexes of acidic cations relevant for radiopharmaceutical applications (i.e., Sc3+).

Experimental and Computational Section

Materials

The H4CHXOCTAPA and H4OCTAPA ligands were prepared as described in previous papers.31,38 All other chemicals and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. The complexes used for NMR and photophysical studies were prepared by mixing stoichiometric amounts of the ligand and the corresponding Ln(OTf)3 salts and subsequent adjustment of the pH with diluted NaOH/NaOD solutions.

NMR Spectroscopy

1H NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C in solutions of the complexes in D2O using Bruker Avance 300 or Bruker ARX400 spectrometers. Chemical shifts were referenced by using the residual solvent HDO proton signal (δ = 4.79 ppm).101

The 1H NMRD measurements were carried out by using a Stelar SMARTracer Fast Field Cycling relaxometer (0.01–10 MHz) and a Bruker WP80 NMR electromagnet adapted to variable field measurements (20–80 MHz) controlled by a SMARTracer PC-NMR console. The NMRD profiles of the [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− complex (ccomplex = 2.69 mM) were recorded in aqueous solution at three different temperatures (25, 37 and 50 °C) in the presence of 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid buffer (25 mM, pH = 7.27) to maintain the pH constant. The temperature of the samples was managed by a VTC91 temperature control unit (calibrated by a Pt resistance temperature probe) and maintained by gas flow.

Transverse and longitudinal 17O relaxation rates (1/T2, 1/T1) and chemical shifts were measured in aqueous solutions of [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− (0.0199 mM, pH = 7.27) in the temperature range 274–354 K on a Bruker Avance 400 (9.4 T, 54.24 MHz) spectrometer. The temperature was calculated according to previous calibration with ethylene glycol and methanol.102 An acidified water solution (HClO4, pH 3.3) was used as an external reference. Longitudinal relaxation times (T1) were obtained by the inversion–recovery method, and transverse relaxation times (T2) were obtained by the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill spin-echo technique.103 The technique used for 17O NMR measurements on Gd3+ complexes has been described elsewhere.104 The samples were sealed in glass spheres fitted into 10 mm NMR tubes to avoid susceptibility corrections of the chemical shifts.105 To improve the sensitivity, 17O-enriched water (10% H217O, CortecNet) was added to the solutions to reach around 2% enrichment. The 17O NMR data were treated according to the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan theory of paramagnetic relaxation. The least-squares fit of the 17O NMR and 1H NMRD data was performed using Micromath Scientist version 2.0 (Salt Lake City, UT, USA).

Absorption and Emission Electronic Spectroscopy

The absorption spectra of the Eu3+ and Tb3+ complexes were recorded with a Jasco V-650 spectrometer using 0.2 cm quartz cells. Steady-state emission spectra were obtained with a Horiba FluoroMax Plus-P spectrofluorometer using a 150 W ozone-free xenon arc lamp as the excitation source, a R928P photon counting emission detector, and an integration time of 0.1 s. Luminescence lifetimes were measured using the time-correlated single photon counting technique and a pulsed xenon flash lamp as the excitation source. Quantum yields were determined using the Cs3[Ln(pic)3] complexes (pic = 2,6-dipicolinate, Ln = Eu or Tb) as standards (ΦEu = 24% in TRIS, pH 7.4, 7.5 × 10–5 M; ΦTb = 22% in TRIS, pH 7.4, 6.5 × 10–5 M).53,54

Equilibrium Studies

The chemicals (MCl2 and LnCl3 salts) used in the studies were of the highest analytical grade obtained from commercial sources (Sigma-Aldrich and Strem Chemicals Inc.). The concentration of the stock solutions was determined by complexometric titration using a standardized Na2H2EDTA solution and appropriate indicators (Patton & Reeder (CaCl2), Eriochrome Black T (MgCl2), xylenol orange (ZnCl2 and LnCl3), and murexide (CuCl2)).

The pH potentiometric titrations were carried out with a Metrohm 888 Titrando titration workstation using a Metrohm-6.0233.100 combined electrode. The titrated solutions (6.00 mL) were thermostated at 25 °C, and samples were stirred and kept under an inert gas atmosphere (N2) to avoid the presence of CO2. The calibration of the electrode was performed by a two-point calibration [KH-phthalate (pH = 4.005) and borax (pH = 9.177) buffers] routine. The calculation of [H+] from the measured pH values was performed with the use of the method proposed by Irving et al.106 by titrating a 0.01 M HCl solution (I = 0.15 M NaCl) with a standardized NaOH solution. The differences between the measured (pHread) and calculated pH (−log [H+]) values were used to obtain the equilibrium H+ concentrations from the pH data obtained in the titrations. The ion product of water (pKW = 13.847) was determined from the same experiment in the pH range 11.2–11.85.

The concentration of the CHXOCTAPA4− chelator was determined by pH potentiometric titration, comparing the titration curves obtained in the presence and absence of high Ca2+ excess (the concentration of the ligand in the titration was 4.38 mM). The protonation constants of CHXOCTAPA4−, the stability and protonation constants of the complexes formed with Mg2+, Ca2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+, as well as those of La3+, Gd3+, and Yb3+ were also determined by pH potentiometric titration. The metal-to-ligand concentration ratios were 1:1 and 2:1 (the concentration of the ligand in these titrations was generally 2.50–3.00 mM). The pH potentiometric titration curves were measured in the pH range 1.70–11.85, while 122–356 mL NaOH-pH data pairs were recorded and fitted simultaneously.

Due to the high conditional stability of [Cu(CHXOCTAPA)]2–, the formation of the complex was complete (nearly 100%) even at pH = 1.75 (starting point of the pH potentiometric titrations). For this reason, 12 out-of-cell (batch) samples containing a slight excess of ligand and the Cu2+ ion were prepared ([L] = 3.110 mM, [Cu2+] = 3.065 mM, 25 °C, 3.0 M (Na+ + H+)Cl–). The samples, whose acidity was varied in the concentration range of 0.1005–3.007 M, were equilibrated for 1 day before recording the absorption spectra at 25 °C in Peltier thermostated semimicro 1 cm Hellma cells using a Jasco V-770 UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer. The molar absorptivity of the [Cu(CHXOCTAPA)]2– complex was determined at 25 wavelengths (600–840 nm range) by recording the spectra of 1.501 × 10–3, 3.002 × 10–3, and 4.503 × 10–3 M solutions of the complex, while for the Cu2+ ion, previously published molar absorptivity values (determined under identical conditions) were used for data fitting.107 The molar absorption coefficients of the protonated [CuH(CHXOCTAPA)]− and [CuH2(CHXOCTAPA)] species were calculated during data refinement (UV–visible and pH potentiometric titration curves obtained at various metal to ligand concentrations were fitted simultaneously). The protonation (ligand and complexes) and stability constants (complexes) were calculated from the titration data with the PSEQUAD program.108

Stability constants of the [Zn(CHXOCTAPA)]2–, [La(CHXOCTAPA)]−, and [Yb(CHXOCTAPA)]− complexes were also determined by following the competition reaction of these metal ions with Gd3+ for the ligand, in a similar manner as it was performed for the [M(OCTAPA)]4– complexes.31 A total of 9–11 samples containing nearly 1 mM [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− and 0.5–20.0 mM (La3+), 0.25–35.0 mM (Yb3+), or 0.5–20 mM (Zn2+) metal chlorides were prepared and equilibrated at constant pH (4.69 for La3+, 4.79 for Yb3+, and 4.81 for Zn2+). Longitudinal relaxation times of the samples were measured after 4 weeks (and repeated 4 weeks later to make sure that the equilibrium had been reached) and the formation constants determined by using the relaxivities of the Gd3+ aqua ion and [Gd(CHXOCTAPA)]− (13.26 and 6.16 mM–1 s–1 at 25 °C and 0.49 T, respectively).38

Kinetic Studies

The rates of the metal exchange reactions involving the [Lu(CHXOCTAPA)]− complex and Cu2+ were studied by using UV–vis spectrophotometry following the formation of the [Cu2(CHXOCTAPA)] complex. The conventional UV–vis spectroscopic method was applied to follow the decomplexation reactions of [Lu(CHXOCTAPA)]−, as these reactions were very slow even at relatively low pH (in the pH range 3.27–4.39). The absorbance versus time kinetic curves were acquired by using a Jasco V-770 UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer equipped with Peltier thermostatted multicell holder. The temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and the ionic strength of the solutions was kept constant by using 0.15 M NaCl. For keeping the pH constant, 50 mM DMP buffer was used (log K2H = 4.19(5) as determined by using pH-potentiometry at 25 °C with the use of 0.15 M NaCl ionic strength). The exchange reactions were followed continuously at 300 nm for 4–5 days (80–95% conversion) and occasionally (one or two readouts per day) for another 5–7 days. The absorbance readings at equilibrium were determined 3–4 weeks after the start of the reaction depending on the pH of the samples (8–10 times longer than the half-life of the reaction). The concentration of the [Lu(CHXOCTAPA)]− chelate was 0.52 mM, while the Cu2+ ion was applied at high excess (10.6–42.6 fold) in order to ensure pseudo-first order conditions. The pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobs) were calculated by fitting the absorbance–time data pairs to eq 8

| 8 |

where At, A0, and Ae are the absorbance at time t, at the start, and at equilibrium, respectively. The pseudo-first-order rate constants were fitted with the computer program Micromath Scientist, version 2.0 (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) by using a standard least-squares procedure.

Computational Studies

The geometries of the [Ln(OCTAPA)(H2O)]−·2H2O and [Ln(CHXOCTAPA)(H2O)]−·2H2O systems (Ln = La, Pr, Gd, Yb, or Lu) were optimized using DFT calculations with the M062X109 exchange correlation functional. Two explicit second-sphere water molecules were considered in these models for a more appropriate description of the interaction between the metal ion and the coordinated water molecule.110 Relativistic effects were considered with the pseudopotential approximation using either the large-core quasi-relativistic effective core potentials (ECP) developed by Dolg et al. ([Kr]4d104fn core)111 and the (14s6p5d)/[2s1p1d]-GTO valence basis sets (Ln = Pr, Gd, Yb and Lu) or the small-core quasi-relativistic ECP (1s–3d electrons in the core)112 and the associated (42s26p20d8f)/[3s2p2d1f] valence basis set (Ln = La). All other atoms were described using the standard 6-311G(d,p) basis set. Bulk solvent effects were incorporated using the integral equation formalism implementation of the polarized continuum model.113 Frequency calculations were performed to confirm that geometry optimizations provided local energy minima on the corresponding potential energy surfaces. All pseudopotential calculations were carried out with the Gaussian 16 program.114

Hyperfine and quadrupole coupling constants115 of the O atoms of water molecules coordinated to Gd3+ were estimated with DFT using the ORCA4 program package116,117 and a Gaussian finite model.118 In these calculations, we used the hybrid meta-GGA TPSSh functional,119 which was found to provide good estimates of hyperfine coupling constants in Gd3+110,120 and other metal complexes.121 Relativistic effects were introduced with the Douglas–Kroll–Hess (DKH2) method,122,123 using the SARC2-DKH-QZVP124 for Gd and the DKH-def2-TZVPP125 basis set for all other atoms. The resolution of identity and chain of spheres126,127 algorithm was used to speed up the calculation with the aid of auxiliary basis sets generated with the Autoaux128 procedure for Gd and the SARC/J auxiliary basis set for all other atoms (decontracted Def2/J).129 Bulk solvent effects were considered with the SMD solvation model developed by Truhlar.130

Acknowledgments

F.L.-M., D.E.-G., and C.P.-I. thank Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Grant PID2019-104626GB-I00) and Xunta de Galicia (ED431B 2020/52) for generous financial support. The authors thank the financial support for the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH K-128201, 134694 and FK-134551 projects). G.T. and C.P.-I. gratefully acknowledge the bilateral Hungarian–Spanish Science and Technology Cooperation Program (2019-2.1.11-TET-2019-00084 supported by NKFIH). B.V. was supported by the Doctoral School of Chemistry at the University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary. This publication and the scientific research were supported by the Gedeon Richter’s Talentum Foundation established by Gedeon Richter Plc (Gedeon Richter Ph.D. Fellowship). The research was prepared with the professional support of the Doctoral Student Scholarship Program of the Cooperative Doctoral Program of the Ministry of Innovation and Technology financed from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (NKFIH). The research was supported by the ÚNKP-21-4 new national excellence program of the Ministry of Human Capacities (F.K.K.) and the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (F.K.K.). The authors are indebted to Centro de Supercomputación de Galicia (CESGA) for providing the computer facilities. C.P.-I. thanks Prof. M. Mazzanti for noticing that the emission quantum yields reported previously for OCTAPA4– complexes were incorrect. Funding for open access provided by Universidade da Coruña/CISUG.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c00501.

Absorption and emission spectra, NMR spectra, speciation diagrams, analysis of the Yb3+-induced paramagnetic shifts, bond distances, and optimized geometries obtained with DFT (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wahsner J.; Gale E. M.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez A.; Caravan P. Chemistry of MRI Contrast Agents: Current Challenges and New Frontiers. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 957–1057. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffern M. C.; Matosziuk L. M.; Meade T. J. Lanthanide Probes for Bioresponsive Imaging. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4496–4539. 10.1021/cr400477t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Meade T. J. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Gd(III)-Based Contrast Agents: Challenges and Key Advances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17025–17041. 10.1021/jacs.9b09149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre V. C.; Harris S. M.; Pailloux S. L. Comparing Strategies in the Design of Responsive Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Case Study with Copper and Zinc. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 342–351. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelovski G.; Tóth É. Strategies for Sensing Neurotransmitters with Responsive MRI Contrast Agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 324–336. 10.1039/c6cs00154h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünzli J.-C. G. Lanthanide Luminescence for Biomedical Analyses and Imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2729–2755. 10.1021/cr900362e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünzli J.-C. G. On the Design of Highly Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 293–294, 19–47. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nonat A. M.; Charbonnière L. J. Upconversion of Light with Molecular and Supramolecular Lanthanide Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 409, 213192. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kostelnik T. I.; Orvig C. Radioactive Main Group and Rare Earth Metals for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 902–956. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn B. A.; Koller A. J.; Chen Z.; Ahn S. H.; Loveless C. S.; Cingoranelli S. J.; Yang Y.; Cirri A.; Johnson C. J.; Lapi S. E.; Chapman K. W.; Boros E. Homologous Structural, Chemical, and Biological Behavior of Sc and Lu Complexes of the Picaga Bifunctional Chelator: Toward Development of Matched Theranostic Pairs for Radiopharmaceutical Applications. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32, 1232–1241. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyai Z.; Pálinkás Z.; Uggeri F.; Maiocchi A.; Aime S.; Brücher E. Dissociation Kinetics of Open-Chain and Macrocyclic Gadolinium(III)-Aminopolycarboxylate Complexes Related to Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Catalytic Effect of Endogenous Ligands. Chem.—Eur.J. 2012, 18, 16426–16435. 10.1002/chem.201202930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyai Z.; Brücher E.; Uggeri F.; Maiocchi A.; Tóth I.; Andrási M.; Gáspár A.; Zékány L.; Aime S. The Role of Equilibrium and Kinetic Properties in the Dissociation of Gd[DTPA-Bis(Methylamide)] (Omniscan) at near to Physiological Conditions. Chem.—Eur.J. 2015, 21, 4789–4799. 10.1002/chem.201405967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros E.; Packard A. B. Radioactive Transition Metals for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 870–901. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuvaev S.; Starck M.; Parker D. Responsive, Water-Soluble Europium(III) Luminescent Probes. Chem.—Eur.J. 2017, 23, 9974–9989. 10.1002/chem.201700567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough T. J.; Jiang L.; Wong K.-L.; Long N. J. Ligand Design Strategies to Increase Stability of Gadolinium-Based Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1420. 10.1038/s41467-019-09342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann P.; Kotek J.; Kubíček V.; Lukeš I. Gadolinium(III) Complexes as MRI Contrast Agents: Ligand Design and Properties of the Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2008, 23, 3027–3047. 10.1039/b719704g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyai Z.; Uggeri F.; Giovenzana G. B.; Bényei A.; Brücher E.; Aime S. Equilibrium and Kinetic Properties of the Lanthanoids(III) and Various Divalent Metal Complexes of the Heptadentate Ligand AAZTA. Chem.—Eur.J. 2009, 15, 1696–1705. 10.1002/chem.200801803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritmon T. F.; Goedken M. P.; Choppin G. R. The Complexation of Lanthanides by Aminocarboxylate Ligands—I. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1977, 39, 2021–2023. 10.1016/0022-1902(77)80538-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tei L.; Baranyai Z.; Brücher E.; Cassino C.; Demicheli F.; Masciocchi N.; Giovenzana G. B.; Botta M. Dramatic Increase of Selectivity for Heavy Lanthanide(III) Cations by Tuning the Flexibility of Polydentate Chelators. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 616–625. 10.1021/ic901848p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyai Z.; Pálinkás Z.; Uggeri F.; Brücher E. Equilibrium Studies on the Gd3+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ Complexes of BOPTA, DTPA and DTPA-BMA Ligands: Kinetics of Metal-Exchange Reactions of [Gd(BOPTA)]2-. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 1948–1956. 10.1002/ejic.200901261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez A.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Tripier R.; Tircsó G.; Garda Z.; Tóth I.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T.; Platas-Iglesias C. Lanthanide(III) Complexes with a Reinforced Cyclam Ligand Show Unprecedented Kinetic Inertness. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17954–17957. 10.1021/ja511331n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh E.; Tripier R.; Ruloff R.; Tóth É. Kinetics of Formation and Dissociation of Lanthanide(iii) Complexes with the 13-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand TRITA4–. Dalton Trans. 2005, 6, 1058–1065. 10.1039/b418991d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth E.; Brucher E.; Lazar I.; Toth I. Kinetics of Formation and Dissociation of Lanthanide(III)-DOTA Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 4070–4076. 10.1021/ic00096a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. L.; Horrocks W. D. Kinetics of Complex Formation by Macrocyclic Polyaza Polycarboxylate Ligands: Detection and Characterization of an Intermediate in the Eu3+-Dota System by Laser-Excited Luminescence. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 3724–3732. 10.1021/ic00118a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarka L.; Burai L.; Brücher E. The Rates of the Exchange Reactions between [Gd(DTPA)]2- and the Endogenous Ions Cu2+ and Zn2+: A Kinetic Model for the Prediction of the In Vivo Stability of [Gd(DTPA)]2-, Used as a Contrast Agent in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Chem.—Eur. J. 2000, 6, 719–724. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platas-Iglesias C.; Mato-Iglesias M.; Djanashvili K.; Muller R. N.; Elst L. V.; Peters J. A.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Lanthanide Chelates Containing Pyridine Units with Potential Application as Contrast Agents in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Chem.—Eur.J. 2004, 10, 3579–3590. 10.1002/chem.200306031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton N.; Gateau C.; Mazzanti M.; Pécaut J.; Borel A.; Helm L.; Merbach A. The Effect of Pyridinecarboxylate Chelating Groups on the Stability and Electronic Relaxation of Gadolinium Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2005, 6, 1129–1135. 10.1039/b416150e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel A.; Laus S.; Ozarowski A.; Gateau C.; Nonat A.; Mazzanti M.; Helm L. Multiple-Frequency EPR Spectra of Two Aqueous Gd3+ Polyamino Polypyridine Carboxylate Complexes: A Study of High Field Effects. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 5399–5407. 10.1021/jp066921z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaraquemada-Peláez M. d. G.; Wang X.; Clough T. J.; Cao Y.; Choudhary N.; Emler K.; Patrick B. O.; Orvig C. H4Octapa: Synthesis, Solution Equilibria and Complexes with Useful Radiopharmaceutical Metal Ions. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 14647–14658. 10.1039/c7dt02343j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. W.; Cawthray J. F.; Bailey G. A.; Ferreira C. L.; Boros E.; Adam M. J.; Orvig C. H4Octapa: An Acyclic Chelator for 111In Radiopharmaceuticals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8670–8683. 10.1021/ja3024725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kálmán F. K.; Végh A.; Regueiro-Figueroa M.; Tóth É.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Tircsó G. H4Octapa: Highly Stable Complexation of Lanthanide(III) Ions and Copper(II). Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 2345–2356. 10.1021/ic502966m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. W.; Zeglis B. M.; Cawthray J. F.; Lewis J. S.; Adam M. J.; Orvig C. What a Difference a Carbon Makes: H4 Octapa vs H4 C3octapa, Ligands for In-111 and Lu-177 Radiochemistry. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 10412–10431. 10.1021/ic501466z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. W.; Cawthray J. F.; Adam M. J.; Orvig C. Modular Syntheses of H4Octapa and H2Dedpa, and Yttrium Coordination Chemistry Relevant to 86Y/ 90Y Radiopharmaceuticals. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 7176–7190. 10.1039/c4dt00239c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. W.; Zeglis B. M.; Cawthray J. F.; Ramogida C. F.; Ramos N.; Lewis J. S.; Adam M. J.; Orvig C. Versatile Acyclic Chelate System for 111In and 177Lu Imaging and Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12707–12721. 10.1021/ja4049493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. W.; Edwards K. J.; Carnazza K. E.; Carlin S. D.; Zeglis B. M.; Adam M. J.; Orvig C.; Lewis J. S. A Comparative Evaluation of the Chelators H4Octapa and CHX-A″-DTPA with the Therapeutic Radiometal 90Y. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2016, 43, 566–576. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Kuo H.-T.; Wang X.; Merkens H.; Colpo N.; Radchenko V.; Schaffer P.; Lin K.-S.; Bénard F.; Orvig C. tBu4Octapa-Alkyl-NHS for Metalloradiopeptide Preparation. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 7605–7619. 10.1039/d0dt00845a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramogida C. F.; Cawthray J. F.; Boros E.; Ferreira C. L.; Patrick B. O.; Adam M. J.; Orvig C. H2CHXDedpa and H4 CHXOctapa—Chiral Acyclic Chelating Ligands for 67/68Ga and 111In Radiopharmaceuticals. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 2017–2031. 10.1021/ic502942a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tircsó G.; Regueiro-Figueroa M.; Nagy V.; Garda Z.; Garai T.; Kálmán F. K.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Tóth É.; Platas-Iglesias C. Approaching the Kinetic Inertness of Macrocyclic Gadolinium(III)-Based MRI Contrast Agents with Highly Rigid Open-Chain Derivatives. Chem.—Eur.J. 2016, 22, 896–901. 10.1002/chem.201503836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez A.; Garda Z.; Ruscsák E.; Esteban-Gómez D.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T.; Lima L. M. P.; Beyler M.; Tripier R.; Tircsó G.; Platas-Iglesias C. Stable Mn2+ , Cu2+ and Ln3+ Complexes with Cyclen-Based Ligands Functionalized with Picolinate Pendant Arms. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 5017–5031. 10.1039/c4dt02985b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm L.; Morrow J. R.; Bond C. J.; Carniato F.; Botta M.; Braun M.; Baranyai Z.; Pujales-Paradela R.; Regueiro-Figueroa M.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Scholl T. J.. Chapter 2. Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents. In New Developments in NMR; Pierre V. C., Allen M. J., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2017; pp 121–242. [Google Scholar]

- Regueiro-Figueroa M.; Esteban-Gómez D.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T.; Platas-Iglesias C. Understanding Stability Trends along the Lanthanide Series. Chem.—Eur.J. 2014, 20, 3974–3981. 10.1002/chem.201304469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Sabio A.; Mato-Iglesias M.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Tóth É.; Blas A. d.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Macrocyclic Receptor Exhibiting Unprecedented Selectivity for Light Lanthanides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3331–3341. 10.1021/ja808534w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu A.; MacMillan S. N.; Wilson J. J. Macrocyclic Ligands with an Unprecedented Size-Selectivity Pattern for the Lanthanide Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13500–13506. 10.1021/jacs.0c05217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele N. A.; Woods J. J.; Wilson J. J. Implementing F-Block Metal Ions in Medicine: Tuning the Size Selectivity of Expanded Macrocycles. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 10483–10500. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyai Z.; Tei L.; Giovenzana G. B.; Kálmán F. K.; Botta M. Equilibrium and NMR Relaxometric Studies on the s-Triazine-Based Heptadentate Ligand PTDITA Showing High Selectivity for Gd3+ Ions. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 2597–2607. 10.1021/ic202559h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods J. J.; Unnerstall R.; Hasson A.; Abou D. S.; Radchenko V.; Thorek D. L. J.; Wilson J. J. Stable Chelation of the Uranyl Ion by Acyclic Hexadentate Ligands: Potential Applications for 230 U Targeted α-Therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 3337–3350. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c03972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takács A.; Napolitano R.; Purgel M.; Bényei A. C.; Zékány L.; Brücher E.; Tóth I.; Baranyai Z.; Aime S. Solution Structures, Stabilities, Kinetics, and Dynamics of DO3A and DO3A–Sulphonamide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2858–2872. 10.1021/ic4025958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gündüz S.; Vibhute S.; Botár R.; Kálmán F. K.; Tóth I.; Tircsó G.; Regueiro-Figueroa M.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Angelovski G. Coordination Properties of GdDO3A-Based Model Compounds of Bioresponsive MRI Contrast Agents. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 5973–5986. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacheris W. P.; Nickle S. K.; Sherry A. D. Thermodynamic Study of Lanthanide Complexes of 1,4,7-Triazacyclononane-N,N’,N″-Triacetic Acid and 1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-N,N’,N’’,N’’’-Tetraacetic Acid. Inorg. Chem. 1987, 26, 958–960. 10.1021/ic00253a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Supkowski R. M.; Horrocks W. D. On the Determination of the Number of Water Molecules, q, Coordinated to Europium(III) Ions in Solution from Luminescence Decay Lifetimes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2002, 340, 44–48. 10.1016/s0020-1693(02)01022-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beeby A.; Clarkson I. M.; Dickins R. S.; Faulkner S.; Parker D.; Royle L.; de Sousa A. S.; Williams J. A. G.; Woods M. Non-Radiative Deactivation of the Excited States of Europium, Terbium and Ytterbium Complexes by Proximate Energy-Matched OH, NH and CH Oscillators: An Improved Luminescence Method for Establishing Solution Hydration States. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 3, 493–504. 10.1039/a808692c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin A. S.; Gumy F.; Imbert D.; Bünzli J. C. G. Europium and Terbium Tris(Dipicolinates) as Secondary Standards for Quantum Yield Determination. Spectrosc. Lett. 2004, 37, 517–532. 10.1081/sl-120039700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin A. S.; Gumy F.; Imbert D.; Bunzli J. C. G. Erratum. Spectrosc. Lett. 2007, 40, 193. 10.1080/00387010601158480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werts M. H. V.; Jukes R. T. F.; Verhoeven J. W. The Emission Spectrum and the Radiative Lifetime of Eu3+ in Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 1542–1548. 10.1039/b107770h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. Macrocyclic Ligands with Pendent Amide and Alcoholic Oxygen Donor Groups. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1996, 148, 315–347. 10.1016/0010-8545(95)01190-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Fur M.; Molnár E.; Beyler M.; Fougère O.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Rousseaux O.; Tripier R.; Tircsó G.; Platas-Iglesias C. Expanding the Family of Pyclen-Based Ligands Bearing Pendant Picolinate Arms for Lanthanide Complexation. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 6932–6945. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton N.; Bretonnière Y.; Pécaut J.; Mazzanti M. An Efficient Design for the Rigid Assembly of Four Bidentate Chromophores in Water-Stable Highly Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7595–7598. 10.1002/anie.200502231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guanci C.; Giovenzana G.; Lattuada L.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Charbonnière L. J. AMPED. A New Platform for Picolinate Based Luminescent Lanthanide Chelates. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 7654–7661. 10.1039/c5dt00077g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocton G. g.; Nonat A.; Gateau C.; Mazzanti M. Water Stability and Luminescence of Lanthanide Complexes of Tripodal Ligands Derived from 1,4,7-Triazacyclononane: Pyridinecarboxamide versus Pyridinecarboxylate Donors. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 2257–2273. 10.1002/hlca.200900150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bui A. T.; Beyler M.; Liao Y.-Y.; Grichine A.; Duperray A.; Mulatier J.-C.; Guennic B. L.; Andraud C.; Maury O.; Tripier R. Cationic Two-Photon Lanthanide Bioprobes Able to Accumulate in Live Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 7020–7025. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon N.; Roux A.; Beyler M.; Mulatier J.-C.; Andraud C.; Nguyen C.; Maynadier M.; Bettache N.; Duperray A.; Grichine A.; Brasselet S.; Gary-Bobo M.; Maury O.; Tripier R. Pyclen-Based Ln(III) Complexes as Highly Luminescent Bioprobes for In Vitro and In Vivo One- and Two-Photon Bioimaging Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10184–10197. 10.1021/jacs.0c03496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot A.; D’Aléo A.; Baldeck P. L.; Grichine A.; Duperray A.; Andraud C.; Maury O. Long-Lived Two-Photon Excited Luminescence of Water-Soluble Europium Complex: Applications in Biological Imaging Using Two-Photon Scanning Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1532–1533. 10.1021/ja076837c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnemans K. Interpretation of Europium(III) Spectra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 295, 1–45. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nonat A.; Gateau C.; Fries P. H.; Mazzanti M. Lanthanide Complexes of a Picolinate Ligand Derived from 1,4,7-Triazacyclononane with Potential Application in Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Time-Resolved Luminescence Imaging. Chem.—Eur. J. 2006, 12, 7133–7150. 10.1002/chem.200501390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonat A.; Giraud M.; Gateau C.; Fries P. H.; Helm L.; Mazzanti M. Gadolinium(III) Complexes of 1,4,7-Triazacyclononane Based Picolinate Ligands: Simultaneous Optimization of Water Exchange Kinetics and Electronic Relaxation. Dalton Trans. 2009, 38, 8033–8046. 10.1039/b907738c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonat A. M.Complexes de Lanthanides(III) Pour Le Développement de Nouvelles Sondes Magnétiques et Luminescentes. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Joseph-Fourier—Grenoble I, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mason K.; Harnden A. C.; Patrick C. W.; Poh A. W. J.; Batsanov A. S.; Suturina E. A.; Vonci M.; McInnes E. J. L.; Chilton N. F.; Parker D. Exquisite Sensitivity of the Ligand Field to Solvation and Donor Polarisability in Coordinatively Saturated Lanthanide Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8486–8489. 10.1039/c8cc04995e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickins R. S.; Parker D.; Bruce J.; Tozer D. Correlation of Optical and NMR Spectral Information with Coordination Variation for Axially Symmetric Macrocyclic Eu(III) and Yb(III) Complexes: Axial Donor Polarisability Determines Ligand Field and Cation Donor Preference. Dalton Trans. 2003, 7, 1264–1271. 10.1039/b211939k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z.; Wei C.; Sun B.; Wei H.; Liu Z.; Bian Z.; Huang C. Luminescent Europium(III) Complexes Based on Tridentate Isoquinoline Ligands with Extremely High Quantum Yield. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 41–47. 10.1039/d0qi00894j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs D.; Kiraev S. R.; Phipps D.; Orthaber A.; Borbas K. E. Eu(III) and Tb(III) Complexes of Octa- and Nonadentate Macrocyclic Ligands Carrying Azide, Alkyne, and Ester Reactive Groups. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 106–117. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs D.; Kocsi D.; Wells J. A. L.; Kiraev S. R.; Borbas K. E. Electron Transfer Pathways in Photoexcited Lanthanide(III) Complexes of Picolinate Ligands. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 4244–4254. 10.1039/d1dt00616a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doffek C.; Alzakhem N.; Bischof C.; Wahsner J.; Güden-Silber T.; Lügger J.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Seitz M. Understanding the Quenching Effects of Aromatic C–H- and C–D-Oscillators in Near-IR Lanthanoid Luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16413–16423. 10.1021/ja307339f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I.; Luchinat C.; Parigi G. Magnetic Susceptibility in Paramagnetic NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2002, 40, 249–273. 10.1016/s0079-6565(02)00002-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. A.; Djanashvili K.; Geraldes C. F. G. C.; Platas-Iglesias C. The Chemical Consequences of the Gradual Decrease of the Ionic Radius along the Ln-Series. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 406, 213146. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aime S.; Barbero L.; Botta M.; Ermondi G. Determination of MetaI-Proton Distances and Electronic Relaxation Times in Lanthanide Complexes by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1992, 225–228. 10.1039/dt9920000225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lisowski J.; Sessler J. L.; Lynch V.; Modyi T. D. 1H NMR Spectroscopic Study of Paramagnetic Lanthanide(II1) Texaphyrins. Effect of Axial Ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 2273. 10.1021/ja00113a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lisowski J.; Ripoli S.; Di Bari L. Axial Ligand Exchange in Chiral Macrocyclic Ytterbium(III) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 1388–1394. 10.1021/ic0353918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regueiro-Figueroa M.; Bensenane B.; Ruscsák E.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Charbonnière L. J.; Tircsó G.; Tóth I.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T.; Platas-Iglesias C. Lanthanide Dota-like Complexes Containing a Picolinate Pendant: Structural Entry for the Design of Ln III -Based Luminescent Probes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 4125–4141. 10.1021/ic2001915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vipond J.; Woods M.; Zhao P.; Tircso G.; Ren J.; Bott S. G.; Ogrin D.; Kiefer G. E.; Kovacs Z.; Sherry A. D. A Bridge to Coordination Isomer Selection in Lanthanide(III) DOTA-Tetraamide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 2584–2595. 10.1021/ic062184+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A. F.; Eliseeva S. V.; Carvalho H. F.; Teixeira J. M. C.; Paula C. T. B.; Hermann P.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Petoud S.; Tóth É.; Geraldes C. F. G. C. A Bis(Pyridine N -Oxide) Analogue of DOTA: Relaxometric Properties of the Gd III Complex and Efficient Sensitization of Visible and NIR-Emitting Lanthanide(III) Cations Including Pr III and Ho III. Chem.—Eur.J. 2014, 20, 14834–14845. 10.1002/chem.201403856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. A. The Reliability of Parameters Obtained by Fitting of 1H NMRD Profiles and 17O NMR Data of Potential Gd3+-Based MRI Contrast Agents: Fitting of 1H NMRD Profiles and 17O NMR Data. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2016, 11, 160–168. 10.1002/cmmi.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maigut J.; Meier R.; Zahl A.; Eldik R. v. Triggering Water Exchange Mechanisms via Chelate Architecture. Shielding of Transition Metal Centers by Aminopolycarboxylate Spectator Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14556–14569. 10.1021/ja802842q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon I. Relaxation Processes in a System of Two Spins. Phys. Rev. 1955, 99, 559–565. 10.1103/physrev.99.559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloembergen N. Proton Relaxation Times in Paramagnetic Solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 1957, 27, 572–573. 10.1063/1.1743771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloembergen N.; Morgan L. O. Proton Relaxation Times in Paramagnetic Solutions. Effects of Electron Spin Relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 1961, 34, 842–850. 10.1063/1.1731684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]