Abstract

Several Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains, including one urinary isolate producing an extended-spectrum β-lactamase TEM-24, were isolated from a long-term-hospitalized woman. Three TEM-24-producing enterobacterial species (Enterobacter aerogenes, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis) were isolated from the same patient. TEM-24 and the resistance markers for aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, and sulfonamide were encoded by a 180-kb plasmid transferred by conjugation into E. coli HB101.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) conferring resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins were recently identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17). Most of them are non-SHV, non-TEM-type ESBLs, such as PER-1 (class A enzyme), IMP-1 (class B enzyme), and oxacillinases (class D β-lactamases). All of these β-lactamases are plasmid and/or integron located, with the exception of OXA-18 (18). To our knowledge, only two cases of SHV-type ESBLs have been reported in P. aeruginosa: SHV-2a in France (P. Nordmann, L. Philippon, E. Ronco, and T. Naas, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C-24, 1997) and SHV-5 in Thailand (P. M. Hawkey, A. Chanawong, A. Lulitanond, J. Heritage, F. H. M'Zali, S. Bass, and V. Keer, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C-174a, 1998). The only TEM-derived ESBL described in this species was characterized by Mugnier et al. in 1996 as being TEM-42 (15). This ESBL was encoded by a 18-kb nonconjugative plasmid. In this report, we describe TEM-24 from a P. aeruginosa isolate. The multiplicity of TEM-24-producing bacteria recovered from the same patient strongly suggests the in vivo transfer of this plasmid-mediated ESBL from Enterobacteriaceae to P. aeruginosa.

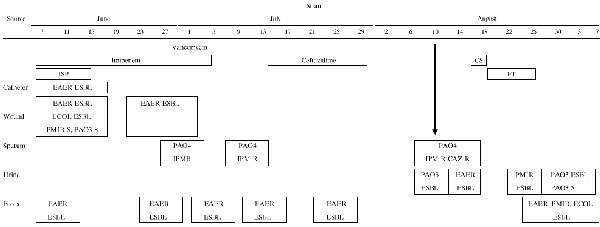

Several ESBL-producing bacteria were isolated from a 66-year-old woman transferred to an intensive care unit (ICU) for severe septic complication after surgery on the sigmoid flexure. Reanimation required mechanically assisted ventilation and central veinous and urinary catheterization. During her hospitalization period (3 months), several infections occurred at various body sites: the postsurgical wound, the central veinous catheter, and the respiratory and urinary tracts. Different antibiotic agents were administered, including imipenem and ceftazidime. At various times during hospitalization, rectal swabs were taken and cultured on Drigalski agar with ceftazidime (4 mg/liter); the different ESBL-producing bacteria were recovered, with the exception of the P. aeruginosa strains. Isolated strains, sites of infection, and antimicrobial treatments are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Isolates, sites of infection and antimicrobial treatmentsa

|

ISP, isepamicin; CS, colistin; FT, nitrofurantoin; S, β-lactam susceptible; IPM R, imipenem resistant; CAZ R, ceftazidime resistant; EAER: E. aerogenes; ECOL; E. coli; PMIR, P. mirabilis; PAO3, P. aeruginosa O:3; PAO4, P. aeruginosa O:4.

Susceptibility tests were first determined by disk diffusion assay on Mueller-Hinton agar according to the recommendations of the Société Française de Microbiologie. ESBL-producing P. aeruginosa appeared to be more resistant to ceftazidime than to cefotaxime. Double-disk synergy tests performed with a 30-mm spacing between the disks (9) were slightly positive when ceftazidime or cefepime disks were used. This test was modified for Enterobacter aerogenes strains with disks placed 20 mm apart or with quartered disks for Proteus mirabilis (14, 16). The three ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains were susceptible to gentamicin and were resistant to tobramycin, netilmicin, and amikacin, suggesting the production of an AAC(6′)-I enzyme. ESBL-producing P. aeruginosa showed higher levels of resistance to tobramycin and netilmicin than to gentamicin.

In order to compare different isolates from the same species, chromosomal DNA was analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). This technique has discriminatory power for the analysis of DNA restriction length polymorphism in P. aeruginosa (22). A total of five E. aerogenes, seven P. aeruginosa, and three P. mirabilis isolates were analyzed. The two Escherichia coli strains which shared the same antibiotype were not compared by PFGE. We also studied three ESBL-producing E. aerogenes isolates recovered from three patients hospitalized at the same time in 3 different ICUs in our hospital. Genomic DNA was prepared as previously described (8). Three restriction enzymes supplied by New England Biolabs were used: XbaI for E. aerogenes, SpeI for P. aeruginosa, and SmaI for P. mirabilis. Digestions were performed with 40 U of each endonuclease for 6 h at 25°C (SmaI) or 37°C (XbaI and SpeI). Lambda ladder (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used as a DNA molecular size marker. PFGE was carried out at 8°C and 4.5 V/cm for 40 h with a CHEF-DR III apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with a 1% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The pulse range was 20 to 5 s for SmaI digests, 40 to 5 s for XbaI digests, and 50 to 10 s for SpeI digests. Gels were stained in ethidium bromide solution and were photographed. The banding patterns were interpreted according to the criteria of Tenover et al. (23).

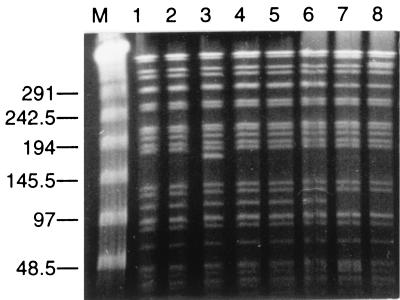

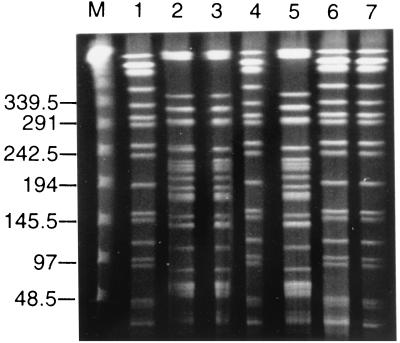

Surprisingly, the PFGE pattern of E. aerogenes recovered from our patient who was colonized before his admission (Table 1) was indistinguishable or closely related to those of E. aerogenes isolates from various ICUs in our hospital (Fig. 1). These results suggested the spread of a single strain in different nursing homes from our district. Such outbreaks due to TEM-24-producing E. aerogenes have been previously reported in many French hospitals (2, 7, 16). P. mirabilis strains including ceftazidime-susceptible and ESBL-producing strains were closely related by PFGE (data not shown). Among P. aeruginosa isolates, two unrelated PFGE patterns were detected: the first one corresponded to isolates from surgical wound and urine samples, the second one corresponded to isolates from sputum samples (Fig. 2). These results were consistent with those of serogrouping determined with antisera from Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur (Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Strains from the first pulsotype belonged to serogroup O:3 (PAO3), and all isolates from the respiratory tract belonged to serogroup O:4 (PAO4). Thus, both β-lactam-susceptible and ESBL-producing strains of P. aeruginosa belonged to serotype O:3 and shared the same PFGE pattern.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of total XbaI-restricted DNA from ESBL-producing E. aerogenes strains. M, lambda ladder. ESBL-producing E. aerogenes strains were isolated from a patient's postsurgical wound (lanes 1 and 2), feces (lanes 3 and 4), and urine (lane 5). ESBL-producing E. aerogenes strains were isolated from three other patients hospitalized in three different ICUs in our hospital (lanes 6 to 8). The size of the ladder is indicated in kilobases.

FIG. 2.

PFGE of total SpeI-restricted DNA from P. aeruginosa strains. M, lambda ladder. P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from the same patient's wound (lane 1), urine (lanes 4 and 6, ESBL-producing P. aeruginosa; lane 7, β-lactam susceptible P. aeruginosa), and sputum (lane 2, 3, and 5). The sizes are indicated in kilobases.

Based on these results, only four strains (E. aerogenes, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and P. mirabilis) were studied for their ESBL. Transconjugants were obtained at high frequency (10−4) in E. coli HB101 resistant to rifampin (20) and were selected on Mueller-Hinton agar containing rifampin (300 μg/ml) and ceftazidime (4 μg/ml). Resistance to aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, and sulfonamides was cotransferred. The MICs of β-lactams were determined for the susceptible PAO3 strain, the multidrug-resistant PAO4 strain, and the four ESBL-producing species and their transconjugants by the dilution method on Mueller-Hinton agar. Plates inoculated by means of a Steers inoculator with 104 CFU per spot were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. MICs of ticarcillin, piperacillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, cefepime, and imipenem were determined. Results are summarized in Table 2. As previously described for TEM-24 (6), all ESBL-producing bacteria were resistant to ticarcillin (MICs >128 μg/ml) and showed higher levels of resistance to ceftazidime (MIC range, 8 to >128 μg/ml) than to cefotaxime (MIC range, 0.125 to 64 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of multiresistant clinical isolates and their transconjugants in E. coli HB101

| Straina | MIC (μg/ml) ofb:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIC | PIP | CTX | CAZ | FEP | ATM | IPM | |

| PAO3 S | 32 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| PAO4 CAZ R, IPM R | 64 | 128 | >128 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 64 |

| PAO3 ESBL | >128 | 16 | 64 | >128 | 32 | 32 | 2 |

| Tr PAO3 ESBL | >128 | 16 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | ND |

| E. aerogenes | >128 | 64 | 8 | >128 | 1 | 16 | 1 |

| Tr E. aerogenes | >128 | 16 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | ND |

| E. coli | >128 | 16 | 0.5 | 128 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Tr E. coli | >128 | 16 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | ND |

| P. mirabilis | >128 | 16 | 0.12 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Tr P. mirabilis | >128 | 16 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | ND |

Tr, transconjugant in E. coli HB101; PAO3 S, first susceptible P. aeruginosa strain isolated from wound; PAO4 CAZ R, IPM R, multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa from sputum; PAO3 ESBL, ESBL-producing P. aeruginosa from urinary tract.

TIC, ticarcillin; PIP, piperacillin; CTX, cefotaxime; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; ATM, aztreonam; IPM, imipenem; ND, not determined.

Plasmid DNA from the four ESBL-producing strains and their transconjugants was prepared by the procedure of Kado and Liu (10) and was electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel for 90 min at 50 V in order to determine the size of the plasmids. All strains harbored a plasmid of approximately 180 kb. A restriction analysis of the plasmid DNA with EcoRI and SalI enzymes was performed (20). Similar restriction patterns were observed from the different plasmids. After Southern blot transfer, hybridization with an intragenic TEM-1-derived probe labelled with 32P was obtained with the same EcoRI-SalI fragment of >10 kb (data not shown) (14).

Analytical isoelectric focusing was carried out with the LKB 2117 Multiphor apparatus as previously described (20). All four clinical isolates and transconjugants produced at least one β-lactamase of pI 6.5, consistent with that of TEM-24 β-lactamase (6).

The amino acid sequences were analyzed by allele-specific PCR (24). Genomic DNAs obtained as described previously (13) were amplified with two amplification primers (A and B) specific for TEM genes and with four primers specific for TEM-24 (4, 12). The results revealed four amino acid substitutions encoded by the blaTEM-2 gene: Glu→Lys 104, Arg→Ser 164, Ala→Thr 237, and Glu→Lys 240, according to Ambler nucleotide numbering (1). These substitutions were characteristic of the TEM-24 β-lactamase (4).

In this clinical report, we observe persistent colonization and infection by a TEM-24-producing strain of E. aerogenes. ESBLs were first characterized in Klebsiella pneumoniae, and over 75 TEM and SHV variants are now disseminated worldwide (3, 11) (http://www.lahey.org/studies/temtable.htm). Multiresistant Enterobacter species are becoming important nosocomial pathogens, mainly in ICUs (19). Isolates producing various ESBLs have been recovered in France and elsewhere, sometimes as epidemic strains (7, 16, 19, 21). In this study, the results of PFGE confirmed the spread of a single TEM-24-producing strain of E. aerogenes in our region.

This work also emphasizes the plasmid spread in addition to cross infection in dissemination of resistance. Our results suggest that the TEM-24-encoding plasmid is transferred from E. aerogenes to other gram-negative bacilli, including P. mirabilis and P. aeruginosa. In vivo transfers of ESBL-encoding plasmids have been previously reported (14, 16, 20) but, to our knowledge, never to P. aeruginosa species. First identified in 1988 in a K. pneumoniae clinical isolate after ceftazidime treatment (6), TEM-24 was later found in various species, with a predominance in E. aerogenes (5), and was usually encoded on a 85-kb plasmid (6, 16). In this study, blaTEM-24 was shown to be carried by a large plasmid of 180 kb. This plasmid was recently isolated in our laboratory (14) and demonstrated the capacity to carry additional genes encoding high capacity of transfer.

It may seem surprising that a P. aeruginosa strain would acquire a TEM-type ESBL. Cotransfer of resistance to other agents, such as aminoglycosides, might be a factor leading to the acquisition of the plasmid. However, such antibiotics were not administered to this patient. Moreover, the second clone of P. aeruginosa colonizing the respiratory tract had acquired ceftazidime resistance, probably by the derepression of AmpC-β-lactamase as suggested by MIC results. TEM-24 production by the P. aeruginosa urinary isolate results from a plasmid transfer certainly occurring in the digestive tract. Although this isolate was never recovered from feces, it was isolated first as a β-lactam-susceptible strain among all enterobacteria from a postsurgical wound, which were indistinguishable by PFGE from urinary and stool isolates. Regarding the MICs of ceftazidime for the ESBL-producing bacteria, this treatment probably conferred to these strains a selective advantage. Thus, this study demonstrated that the exchange of ESBL genes from Enterobacteriaceae to P. aeruginosa strains may lead to multiresistant P. aeruginosa strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Isabelle Renaudin and Agnes Bony for their technical assistance, Josiane Campos and Laurent Isson for PFGE analysis, and Bernard Gay for photographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P, Coulson A F W, Frere J-M, Ghuysen J-M, Joris B, Forsman M, Levesque R C, Tibary G, Waley S G. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1991;376:269–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosi C, Davin-Regli A, Bornet C, Mallea M, Pages J-M, Bollet C. Most Enterobacter aerogenes strains in France belong to a prevalent clone. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2165–2169. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2165-2169.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush K, Jacoby G. Nomenclature of TEM β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chanal C, Poupart M C, Sirot D L, Labia R, Sirot J, Cluzel R. Nucleotide sequences of CAZ-2, CAZ-6, and CAZ-7 β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1817–1820. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chanal C, Sirot D, Romaszko J P, Bret L, Sirot J. Survey of prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:127–132. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanal C M, Sirot D L, Petit A, Labia R, Morand A, Sirot J L, Cluzel R. Multiplicity of TEM-derived β-lactamases from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated at the same hospital and relationships between the responsible plasmids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1915–1920. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Champs C, Sirot D, Chanal C, Poupart M C, Dumas M P, Sirot J. Concomitant dissemination of three extended-spectrum β-lactamases among different Enterobacteriaceae isolated in a French hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:441–457. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouby A, Neuwirth C, Bourg G, Bouzigues N, Carles-Nurit M J, Despaux E, Ramuz M. Epidemiological study by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of an outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a geriatric hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:301–305. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.301-305.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarlier V, Nicolas M H, Fournier G, Philippon A. Extended broad-spectrum β-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer β-lactams agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:867–878. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.4.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kado C I, Liu S T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livermore D M. β-Lactamase-mediated resistance and opportunities for its control. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41(Suppl. D):25–41. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_4.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mabilat C, Courvalin P. Development of “oligotyping” for characterization and molecular epidemiology of TEM β-lactamase in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2210–2216. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchandin H, Carrière C, Sirot D, Jean-Pierre H, Darbas H. TEM-24 produced by four different species of Enterobacteriaceae, including Providencia rettgeri, in a single patient. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2069–2073. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mugnier P, Dubrous P, Casin I, Arlet G, Collatz E. A TEM-derived extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2488–2493. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuwirth C, Siebor E, Lopez J, Pechinot A, Kazmierczak A. Outbreak of TEM-24-producing Enterobacter aerogenes in an intensive care unit and dissemination of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase to the other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:76–79. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.76-79.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordmann P, Guibert M. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:128–131. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philippon L N, Naas T, Bouthors A T, Barakett V, Nordmann P. OXA-18, a class D clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2188–2195. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitout J D D, Thompson K S, Hanson N D, Ehrhardt A F, Coudron P, Sanders C C. Plasmid-mediated resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins among Enterobacter aerogenes strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:596–600. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sirot D, De Champs C, Chanal C, Labia R, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Perroux R, Sirot J. Translocation of antibiotic resistance determinants including an extended-spectrum β-lactamase between conjugative plasmids of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1576–1581. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirot D L, Goldstein F W, Soussy C J, Courtieu A L, Husson M O, Lemozy J, Meyran M, Morel C, Perez R, Quentin-Noury C, Reverdy M E, Scheftel J M, Rosembaum M, Rezvani Y. Resistance to cefotaxime and seven other β-lactams in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae: a 3-year survey in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1677–1681. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talon D, Cailleaux V, Thouverez M, Michel-Briand Y. Discriminatory power and usefulness of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in epidemiological studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Hosp Infect. 1996;32:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(96)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu D Y, Ugozzoli L, Pal K B, Wallace R B. Allele-specific enzymatic amplification of beta-globin DNA for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2757–2760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]