Abstract

Background

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are anti‐inflammatory drugs that have proven benefits for people with worsening symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and repeated exacerbations. They are commonly used as combination inhalers with long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABA) to reduce exacerbation rates and all‐cause mortality, and to improve lung function and quality of life. The most common combinations of ICS and LABA used in combination inhalers are fluticasone and salmeterol, budesonide and formoterol and a new formulation of fluticasone in combination with vilanterol, which is now available. ICS have been associated with increased risk of pneumonia, but the magnitude of risk and how this compares with different ICS remain unclear. Recent reviews conducted to address their safety have not compared the relative safety of these two drugs when used alone or in combination with LABA.

Objectives

To assess the risk of pneumonia associated with the use of fluticasone and budesonide for COPD.

Search methods

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), clinicaltrials.gov, reference lists of existing systematic reviews and manufacturer websites. The most recent searches were conducted in September 2013.

Selection criteria

We included parallel‐group randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of at least 12 weeks' duration. Studies were included if they compared the ICS budesonide or fluticasone versus placebo, or either ICS in combination with a LABA versus the same LABA as monotherapy for people with COPD.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted study characteristics, numerical data and risk of bias information for each included study.

We looked at direct comparisons of ICS versus placebo separately from comparisons of ICS/LABA versus LABA for all outcomes, and we combined these with subgroups when no important heterogeneity was noted. After assessing for transitivity, we conducted an indirect comparison to compare budesonide versus fluticasone monotherapy, but we could not do the same for the combination therapies because of systematic differences between the budesonide and fluticasone combination data sets.

When appropriate, we explored the effects of ICS dose, duration of ICS therapy and baseline severity on the primary outcome. Findings of all outcomes are presented in 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEPro.

Main results

We found 43 studies that met the inclusion criteria, and more evidence was provided for fluticasone (26 studies; n = 21,247) than for budesonide (17 studies; n = 10,150). Evidence from the budesonide studies was more inconsistent and less precise, and the studies were shorter. The populations within studies were more often male with a mean age of around 63, mean pack‐years smoked over 40 and mean predicted forced expiratory volume of one second (FEV1) less than 50%.

High or uneven dropout was considered a high risk of bias in almost 40% of the trials, but conclusions for the primary outcome did not change when the trials at high risk of bias were removed in a sensitivity analysis.

Fluticasone increased non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events (requiring hospital admission) (odds ratio (OR) 1.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.50 to 2.12; 18 more per 1000 treated over 18 months; high quality), and no evidence suggested that this outcome was reduced by delivering it in combination with salmeterol or vilanterol (subgroup differences: I2 = 0%, P value 0.51), or that different doses, trial duration or baseline severity significantly affected the estimate. Budesonide also increased non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events compared with placebo, but the effect was less precise and was based on shorter trials (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.62; six more per 1000 treated over nine months; moderate quality). Some of the variation in the budesonide data could be explained by a significant difference between the two commonly used doses: 640 mcg was associated with a larger effect than 320 mcg relative to placebo (subgroup differences: I2 = 74%, P value 0.05).

An indirect comparison of budesonide versus fluticasone monotherapy revealed no significant differences with respect to serious adverse events (pneumonia‐related or all‐cause) or mortality. The risk of any pneumonia event (i.e. less serious cases treated in the community) was higher with fluticasone than with budesonide (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.34); this was the only significant difference reported between the two drugs. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of possible differences in the assignment of pneumonia diagnosis, and because no trials directly compared the two drugs.

No significant difference in overall mortality rates was observed between either of the inhaled steroids and the control interventions (both high‐quality evidence), and pneumonia‐related deaths were too rare to permit conclusions to be drawn.

Authors' conclusions

Budesonide and fluticasone, delivered alone or in combination with a LABA, are associated with increased risk of serious adverse pneumonia events, but neither significantly affected mortality compared with controls. The safety concerns highlighted in this review should be balanced with recent cohort data and established randomised evidence of efficacy regarding exacerbations and quality of life. Comparison of the two drugs revealed no statistically significant difference in serious pneumonias, mortality or serious adverse events. Fluticasone was associated with higher risk of any pneumonia when compared with budesonide (i.e. less serious cases dealt with in the community), but variation in the definitions used by the respective manufacturers is a potential confounding factor in their comparison.

Primary research should accurately measure pneumonia outcomes and should clarify both the definition and the method of diagnosis used, especially for new formulations and combinations for which little evidence of the associated pneumonia risk is currently available. Similarly, systematic reviews and cohorts should address the reliability of assigning 'pneumonia' as an adverse event or cause of death and should determine how this affects the applicability of findings.

Plain language summary

Do inhaled steroids increase the risk of pneumonia in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)?

Why is this question important? Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are drugs that can reduce the occurrence of COPD flare‐ups and improve quality of life. In COPD, ICS are commonly used alongside long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABA). The most common combinations of ICS and LABA inhalers are fluticasone and salmeterol, and budesonide and formoterol, but fluticasone furoate is also used once daily with a new LABA called vilanterol. Lots of studies have shown benefits of ICS, but they can also increase the risk of pneumonia. Added to this concern, pneumonia can be difficult to diagnose, and the severity of pneumonia can be poorly reported in trials. Therefore even though we have reviews on inhaled steroids for COPD, we wanted to do a review exclusively on pneumonia, so we could take a closer look at the evidence.

The overall aim of this review is to assess the risk of pneumonia for people with COPD taking fluticasone or budesonide.

How did we answer the question? We looked for all studies comparing budesonide or fluticasone versus a dummy inhaler (placebo), and all studies comparing their use in combination with a LABA (i.e. budesonide/formoterol, fluticasone propionate/salmeterol, and fluticasone furoate/vilanterol) versus the same dose of LABA alone. This allowed us to assess the risk of ICS used alone or in combination with LABA.

What did we find? We found 43 studies including more than 30,000 people with COPD. More studies used fluticasone (26 studies; 21,247 people) than budesonide (17 studies; 10,150 people). A higher proportion of people in the studies were male (around 70%), and their COPD was generally classed as severe. The last search for studies to include in the review was done in September 2013.

We compared each drug against controls and assessed separately the results of studies that compared ICS versus placebo, and an ICS/LABA combination versus LABA alone. We also conducted an indirect comparison of budesonide and fluticasone based on their effects against placebo, to explore whether one drug was safer than the other.

Fluticasone increased 'serious' pneumonias (requiring hospital admission). Over 18 months, 18 more people of every 1000 treated with fluticasone were admitted to hospital for pneumonia.

Budesonide also increased pneumonias that were classed as 'serious'. Over nine months, six more hospital admissions were reported for every 1000 individuals treated with budesonide. A lower dose of budesonide (320 mcg) was associated with fewer serious pneumonias than a higher dose (640 mcg).

No more deaths overall were reported in the ICS groups compared with controls, and deaths related to pneumonia were too rare to tell either way.

When we compared fluticasone and budesonide versus each other, the difference between them was not clear enough to tell whether one was safer (for pneumonia, requiring a hospital stay, general adverse events and death). The risk of any pneumonia event (i.e. less serious cases that could be treated without going to hospital) was higher with fluticasone than with budesonide.

Evidence was rated to be of high or moderate quality for most outcomes. When an outcome is rated of high quality, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect, but moderate ratings reflect some uncertainty in the findings. Results from the budesonide studies were generally less clear because they were based on fewer people, and the studies were shorter.

Conclusion Budesonide and fluticasone, delivered alone or in combination with LABA, can increase serious pneumonias that result in hospitalisation of people. Neither has been shown to affect the chance of dying compared with not taking ICS. Comparison of the two drugs revealed no difference in serious pneumonias or risk of death. Fluticasone was associated with a higher risk of any pneumonia (i.e. cases that could be treated in the community) than budesonide, but potential differences in the definition used by the respective drug manufacturers reduced our confidence in this finding. These concerns need to be balanced with the known benefits of ICS (e.g. fewer exacerbations, improved lung function and quality of life).

Researchers should remain aware of the risks associated with ICS and should make sure that pneumonia is properly diagnosed in studies.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Fluticasone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Fluticasone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Intervention: fluticasone (alone or with LABA co‐intervention) Comparison: placebo or LABA monotherapy (dependent upon whether fluticasone was given with LABA in the intervention group) Setting: community | |||||

|

Outcomes Follow‐ups presented as weighted means |

Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Fluticasone | ||||

| Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events (requiring hospital admission) Follow‐up: 18 months | 25 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (37 to 51) | OR 1.78 (1.50 to 2.12) | 19,504 (17 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Mortality, all‐cause Follow‐up: 19 months | 58 per 1000 | 58 per 1000 (51 to 65) | OR 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) | 20,861 (22 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Mortality, due to pneumonia Follow‐up: 18 months | 2 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (2 to 5) | OR 1.23 (0.70 to 2.15) | 19,532 (18 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Non‐fatal, serious adverse events (all) Follow‐up: 19 months | 227 per 1000 | 237 per 1000 (225 to 251) | OR 1.06 (0.99 to 1.14) | 20,381 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| All pneumonia events Follow‐up: 22 months | 72 per 1000 | 116 per 1000 (104 to 129) | OR 1.68 (1.49 to 1.90) | 15,377 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 |

| Withdrawals Follow‐up: 18 months | 343 per 1000 | 297 per 1000 (286 to 310) | OR 0.81 (0.77 to 0.86) | 21,243 (26 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio. Unless otherwise stated, subgroup differences between monotherapy studies (fluticasone versus placebo) and combination therapy studies (fluticasone/LABA versus LABA) were not significant. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Wide confidence intervals include significant benefit and harm, based on very few events (‐1 for imprecision). 2More than half the studies did not report the outcome (‐1 for publication bias).

Summary of findings 2. Budesonide for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Budesonide for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Intervention: budesonide (alone or with LABA co‐intervention) Comparison: placebo or LABA monotherapy (dependent upon whether fluticasone was given with LABA in the intervention group) Setting: community | |||||

|

Outcomes Follow‐ups presented as weighted means |

Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Budesonide | ||||

| Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events (requiring hospital admission) Follow‐up: 9 months | 9 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (9 to 24) | OR 1.62 (1.00 to 2.62) | 6472 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 |

| Mortality, all‐cause Follow‐up: 14 months | 17 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (11 to 21) | OR 0.90 (0.65 to 1.24) | 10,009 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

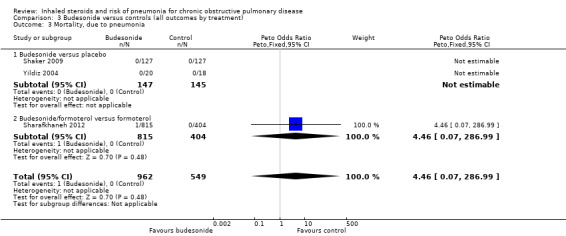

| Mortality, due to pneumonia Follow‐up: 12 months | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | OR 4.46 (0.07 to 286.99) | 1511 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4 |

| Non‐fatal, serious adverse events (all) Follow‐up: 14 months | 145 per 1000 | 146 per 1000 (124 to 172) | OR 1.01 (0.83 to 1.22) | 10,009 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 |

| All pneumonia events Follow‐up: 10 months | 28 per 1000 | 31 per 1000 (23 to 41) | OR 1.12 (0.83 to 1.51) | 7011 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 |

| Withdrawals Follow‐up: 14 months | 280 per 1000 | 232 per 1000 (216 to 248) | OR 0.78 (0.71 to 0.85) | 10150 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio. Unless otherwise stated, subgroup differences between monotherapy studies (budesonide versus placebo) and combination therapy studies (budesonide/LABA versus LABA) were not significant. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Confidence intervals are quite wide but are not considered serious enough to downgrade. 2More than half the studies did not report the outcome (‐1 for publication bias). 3Confidence interval includes significant benefit and potential harm. 4Very wide confidence intervals. Only one death observed over the three studies (‐2 for imprecision). 5I2 = 59%, P value 0.002 (‐1 for inconsistency).

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disease characterised by chronic and progressive breathlessness, cough, sputum production and airflow obstruction, which leads to restricted activity and poor quality of life (GOLD 2013). The World Health Organization (WHO 2012) has estimated that COPD is the fourth or fifth most common single cause of death worldwide, and that the treatment and management costs present a significant burden to public health. In the UK the annual cost of COPD to the National Health Service (NHS) is estimated to be GBP 1.3 million per 100,000 people (NICE 2011). Furthermore, because of its slow onset and under‐recognition of the disease by patients and healthcare professionals, COPD is heavily under diagnosed (GOLD 2013). COPD comprises a combination of bronchitis and emphysema and involves chronic inflammation and structural changes in the lung. Cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor, but air pollution and occupational dust and chemicals are also recognised risk factors. COPD is a progressive disease that leads to decreased lung function over time, even with the best available care. Currently no cure is known for COPD, although the condition is both preventable and treatable. As yet, apart from smoking cessation and non‐pharmacological treatments such as long‐term oxygen therapy in hypoxic patients and pulmonary rehabilitation, no intervention has been shown to reduce mortality (GOLD 2013;Puhan 2011). Management of the disease is multi‐faceted and includes interventions for smoking cessation (Van der Meer 2001), pharmacological treatments (GOLD 2013), education (Effing 2007) and pulmonary rehabilitation (Lacasse 2006; Puhan 2011). Pharmacological therapy is aimed at relieving symptoms, improving exercise tolerance and quality of life, improving lung function and preventing and treating exacerbations.

Description of the intervention

Pharmacological management for COPD is generally a stepwise process, commencing with therapy for symptoms, which is followed by introduction of additional therapeutic agents as needed to achieve control and to reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations (GOLD 2013). Often the first step is to use a short‐acting bronchodilator for control of breathlessness when needed: a short‐acting beta2‐agonist (SABA) (e.g. salbutamol) or the short‐acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) ipratropium. For persistent or worsening breathlessness associated with lung function decline, long‐acting bronchodilators may be introduced (GOLD 2013). These comprise twice‐daily long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABA), such as salmeterol or formoterol; once‐daily beta2‐agonists, such as indacaterol; and the long‐acting anticholinergic agent tiotropium. For patients with severe or very severe COPD (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) < 50% predicted) and with repeated exacerbations, the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD 2013) recommends the addition of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) to bronchodilator treatment. ICS are anti‐inflammatory drugs that are licensed as combination inhalers for use with LABA. The most common ICS and LABA components in combination inhalers are fluticasone propionate and salmeterol, budesonide and formoterol and a new formulation of fluticasone furoate in combination with vilanterol, which is now available for once‐daily use. Patients with severe COPD may also be treated with the phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor roflumilast, which may reduce the risk of exacerbations (GOLD).

How the intervention might work

ICS are anti‐inflammatory drugs. They reduce the rate of exacerbation and improve quality of life, but they have not been found to have an effect on overall mortality or on the long‐term decline in FEV1 (Agarwal 2010; GOLD 2013; Yang 2009). ICS and LABA combination inhalers reduce exacerbation rates and all‐cause mortality and improve lung function and quality of life (Nannini 2013). These effects are thought to be greater for combination inhalers than for the component preparations (GOLD 2013; Nannini 2013). ICS, alone or in combination with LABA, however, have been associated with increased risk of pneumonia (GOLD 2013; Singh 2009). Several mechanisms have been proposed by which ICS could increase the risk of pneumonia; these mechanisms are principally related to the immunosuppressive effects of ICS and include ICS reaching the lung in high concentrations. Particularly, inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) by ICS in COPD, one of the proposed mechanisms for their therapeutic effect, could lead to the suppression of normal host responses to bacterial infection (Singanayagam 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

Use of ICS for treatment of COPD may be beneficial, at least for some COPD patients. But the role of ICS therapy in patients with stable COPD is controversial, especially as an elevated risk of pneumonia has been found in studies of ICS use. Pneumonia in COPD is associated with high morbidity and mortality (Ernst 2007) and worsening quality of life and pulmonary function, so it is important to understand the strength and nature of the association between ICS use and this adverse event.

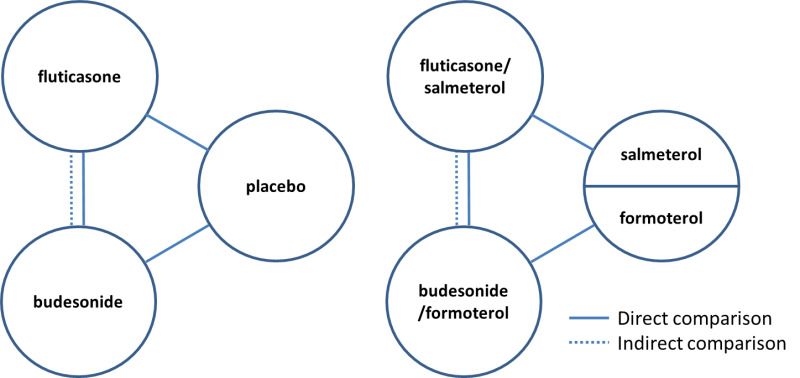

Several systematic reviews published in the last few years have looked at the risk of pneumonia with ICS use (Drummond 2008; Halpin 2011; Sin 2009; Singh 2009). Of these, only one compared different ICS versus each other and as combination inhaler therapy together with a LABA (Halpin 2011). Although ICS are usually administered in a combination inhaler in clinical practice, we are interested in the most comprehensive evidence on the risk of pneumonia with ICS. Differences in the molecular structures of ICS formulations are known to alter their relative potency ratios and durations of action (Johnson 1998; Rossios 2011), but potential differences between formulations in the magnitude of pneumonia risk remains unclear. It is also uncertain whether the association with pneumonia is altered by LABA in combination inhalers. We therefore included studies that examined ICS treatment both alone and in combination with a LABA. We focused on the risk of pneumonia with the two most frequently prescribed ICS—fluticasone and budesonide—compared with control, and on the difference in risk of pneumonia between these ICS. When there was a paucity of head‐to‐head trials directly comparing fluticasone and budesonide, we planned to complement the direct comparisons with an adjusted indirect comparison of budesonide and fluticasone using placebo as a common comparator (Figure 1). Indirect comparisons are considered valid if 'clinical and methodological homogeneity' is present between the budesonide and fluticasone studies (Cipriani 2013). The indirect comparison of budesonide and fluticasone when taken in a combination inhaler with different LABA assumes that the LABA salmeterol, formoterol and vilanterol do not have an important effect on the risk of pneumonia.

1.

Direct and indirect comparisons of fluticasone and budesonide covered in the review.

Objectives

To assess the risk of pneumonia associated with the use of fluticasone and budesonide for COPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a parallel‐group design of at least 12 weeks' duration. We did not exclude studies on the basis of blinding. Cross‐over trials were not included, as ICS can have long‐acting effects, and because the primary outcome is an adverse event.

Types of participants

We included RCTs that recruited participants with a diagnosis of COPD (e.g. based on criteria recommended by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society) (ATS/ERS 2004).

Forced expiratory volume after one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio < 0.7, which confirms the presence of persistent airflow limitation.

-

One or more of the following key indicators.

Progressive and/or persistent dyspnoea.

Chronic cough.

Chronic sputum production.

History of exposure to risk factors (tobacco smoke, smoke from home cooking and heating fuels, occupational dusts and chemicals).

Types of interventions

We included studies that performed any of the following comparisons.

Fluticasone versus placebo.

Budesonide versus placebo.

Fluticasone/salmeterol versus salmeterol.

Fluticasone/vilanterol versus vilanterol.

Budesonide/formoterol versus formoterol.

Fluticasone versus budesonide.

Fluticasone/salmeterol versus budesonide/formoterol.

Fluticasone/vilanterol versus budesonide/formoterol.

We allowed ICS/LABA combination treatment in a single inhaler and in separate inhalers. Participants were allowed to take other concomitant COPD medications as prescribed by their healthcare practitioner provided they were not part of the trial treatment under study. For example, we excluded studies that compared triple therapy of budesonide/formoterol combination inhaler plus tiotropium versus formoterol plus tiotropium.

Types of outcome measures

We were interested in events of pneumonia. Pneumonia is usually defined as an acute lower respiratory tract infection that generally includes symptoms and signs from the respiratory tract and noted in the general health of the patient, but the specific definition/diagnosis varies. We recorded the basis of diagnosis, specifically, radiological confirmation, and planned to conduct a subgroup analysis. One example of the definition of diagnostic criteria for pneumonia is found in BTS 2009.

Symptoms of an acute lower respiratory tract illness (cough and at least one other lower respiratory tract symptom).

New focal chest signs on examination.

At least one systemic feature (either a symptom complex of sweating, fevers, shivers, aches and pains and/or temperature of 38°C or higher).

No other explanation for the illness.

We primarily looked at pneumonia events leading to hospital admissions (i.e. serious adverse pneumonia events), which usually are better documented and diagnosed by imaging studies and laboratory investigations than pneumonia events of any severity, and are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. One example of the definition of diagnostic criteria for pneumonia in hospital is found in BTS 2009.

Symptoms and signs consistent with an acute lower respiratory tract infection associated with new radiographic shadowing for which no other explanation is known (e.g. not pulmonary oedema or infarction).

The illness is the primary reason for hospital admission and is managed as pneumonia.

We used end of study as the time of analysis for all studies, which ranged from three to 36 months in duration.

Primary outcomes

Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events (requiring hospital admission).

We chose serious adverse pneumonia events as the primary outcome because of the increased burden these events have on the individual and on healthcare systems.

Secondary outcomes

Mortality: all‐cause and due to pneumonia.

Non‐fatal serious adverse events: all‐cause.

All pneumonia events.

Withdrawals.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator for the Group. The Register contains trial reports identified by systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and conference abstracts found through handsearching (see Appendix 1 for further details). We searched all records in the CAGR coded 'COPD' using the following terms.

((steroid* or corticosteroid*) and inhal*) or ICS or budesonide or fluticasone or pulmicort or flovent or flixotide or symbicort or viani or seretide or advair.

We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov using search terms provided in Appendix 2. We searched all databases with no restriction on date or language of publication up to September 2013.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We searched the manufacturers' websites (AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline) for additional information on studies identified through the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AS and CK) independently screened the titles and abstracts of citations retrieved through literature searches and obtained those deemed to be potentially relevant. We assigned all references to a study identifier and assessed them against the inclusion criteria of this protocol. We resolved disagreements by consensus. Subsequent search updates were screened by AS and KMK.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (KMK and AS or CK) independently extracted information from each included study (recording the data source) for the following characteristics.

Design (study design, total duration of study, number of study centres and locations).

Participants (number randomly assigned to each treatment, mean age, gender, baseline lung function, smoking history, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria).

Interventions (run‐in, intervention and control treatment including concentration and formulation).

Outcomes (definitions of pneumonia events and data on the numbers of participants with one or more events with onset during the treatment period).

We resolved discrepancies in the data by discussion, or by consultation with a third party when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias according to recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) for the following items.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear according to recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

Direct comparisons (fluticasone vs placebo; budesonide vs placebo; fluticasone/LABA vs LABA; budesonide/LABA vs LABA)

We analysed direct pair‐wise comparisons using Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When events were rare, we employed the Peto odds ratio. When count data were available as rate ratios, we transformed them into log rate ratios and analysed them using generic inverse variance (GIV). For the primary outcome, the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome was calculated from the pooled odds ratio and its confidence interval and was applied to appropriate levels of baseline risk.

Indirect comparisons (monotherapy: fluticasone vs budesonide; combination therapy: fluticasone/LABA vs budesonide/LABA)

We also conducted indirect comparisons of fluticasone and budesonide treatments using odds ratios with a 95% CI (Bucher 1997). When available, we planned to combine the indirect evidence with randomly assigned head‐to‐head comparisons of fluticasone and budesonide.

Assessing transitivity and similarity

To permit valid indirect comparisons of fluticasone and budesonide, the sets of trials for each drug must be similar in their distribution of effect modifiers (Cipriani 2013). Before conducting indirect comparisons, we constructed summary tables for monotherapy and combination therapy separately to compare the following characteristics between budesonide and fluticasone trials.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (including allowed co‐medications).

Baseline characteristics (smoking history, % predicted FEV1, age, percentage male).

Intervention characteristics (dose distribution, inhaler device).

Methodology (risk of bias, study duration, sample size, funding).

Control group event rates.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant for dichotomous outcomes, but events were used to compare rates of exacerbation.

Dealing with missing data

When pneumonia data or key study characteristics were not reported in the primary publication, we searched clinical trial reports and contacted study authors and sponsors for additional information. We used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis on outcomes of all randomly assigned participants when possible. We considered the impact of the unknown status of participants who withdrew from the trials as part of the sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by recording differences in study design, participant characteristics, study sponsorship and pneumonia definition between individual studies. We assessed the extent of statistical variation among study results by using the I2 measurement. We tested for inconsistency between direct and indirect data by calculating the log ratio of direct and indirect odds ratios (ROR) (Song 2008).

Assessment of reporting biases

We tried to minimise reporting bias from non‐publication of studies or selective outcome reporting by using a broad search strategy, checking references of included studies and relevant systematic reviews and contacting study authors for additional outcome data. We visually inspected funnel plots when 10 or more studies were included.

Data synthesis

We looked at direct comparisons of ICS versus placebo separately from comparisons of ICS/LABA versus LABA for all outcomes (Figure 1). When no important discrepancy was noted between the analyses with and without LABA, we combined the results. When a study comparing ICS/LABA versus LABA included arms for both a single inhaler (ICS/LABA) and separate inhalers (ICS + LABA), we split the control group (LABA) in half to avoid double‐counting.

The decision whether to perform indirect comparisons of studies was based on our assessment of their clinical and methodological differences.

If both direct and indirect comparison data were available, we planned to combine the estimates using a fixed‐effect model, but when statistical heterogeneity was evident (I2 > 30%), we used a random‐effects model to analyse the data and explore the heterogeneity (see below). When no important discrepancy was noted between direct and indirect estimates, we combined the resulting odds ratio and 95% CI from the indirect comparison with any direct pair‐wise data for the same comparison using inverse variance weighting (Glenny 2005).

We presented the findings of all outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEPro software and recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When appropriate, we explored heterogeneity between studies by analysing data for the primary outcome by looking at the following subgroups.

ICS dose (separate subgroups for each of the following drugs and doses: fluticasone 500 and 1000 mcg; budesonide 320, 640 and 1280 mcg).

Duration of ICS therapy (≤ one year; > one year).

Diagnostic criteria of pneumonia.

Disease severity at baseline (FEV1 < 50% predicted; FEV1 ≥ 50% predicted).

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the robustness of our analyses by performing sensitivity analyses, while systematically excluding studies from the overall analysis:

of high risk of bias; or

with high and or uneven withdrawal rates.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

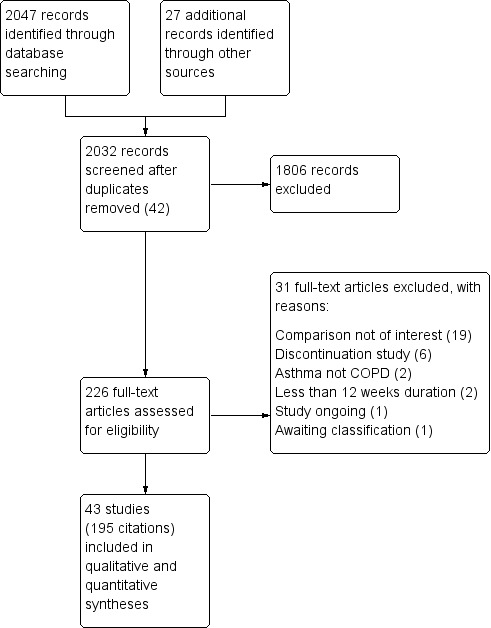

Two thousand forty‐seven citations were identified by searching electronic databases. Twenty‐seven additional citations were found by searching reference lists, clinicaltrials.gov and drug company websites. Forty‐two duplicates were removed, and the remaining 2032 titles and abstracts were sifted. Two review authors excluded 1806 references that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full texts were obtained and scrutinised for the final 226 references, and 195 (representing 43 studies) met all of the inclusion criteria. Figure 2 shows this information as a flow diagram and gives reasons for exclusion of the 31 references that were excluded after the full text was reviewed.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Forty‐three studies met all of the inclusion criteria and were included in the review: 26 using fluticasone and 17 using budesonide as the inhaled steroid. The fluticasone studies included more than twice as many people, with 21,247 people randomly assigned to the treatments of interest compared with 10,067 in the budesonide studies. Two of the included budesonide studies reported no data that could be used in the analyses and are not included in these numbers (Laptseva 2002; Senderovitz 1999).

No studies directly comparing fluticasone with budesonide met the inclusion criteria (either as monotherapy or in their combination preparations), so only indirect evidence was available for these comparisons.

Design and duration

All studies were randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group trials of at least 12 weeks' duration. Most were funded by pharmaceutical companies, predominantly GlaxoSmithKline for the fluticasone studies and AstraZeneca for the budesonide studies. Duration ranged from three to 36 months for both drugs, but mean duration weighted by sample size was longer for the fluticasone studies (fluticasone, 18 months; budesonide, 14 months). A summary of each study and baseline characteristics can be found in Table 3 and Table 4.

1. Fluticasone—summary of studies and baseline characteristics.

| Study ID | Duration (m) | N Rand | Funder | ICS dose (mcg) | % Male | Mean age | Pack‐years | % pred FEV1 |

| Fluticasone versus placebo (n = 18) | ||||||||

| Bourbeau 2007 | 3 | 41 | GSK | 1000 | 78 | 65 | 53 | 57 |

| Burge 2000 | 36 | 740 | GSK | 1000 | 75 | 64 | 44 | 50 |

| Calverley 2003 TRISTANa | 12 | 763 | GSK | 1000 | 73 | 63 | 43 | 45 |

| Calverley 2007 TORCHa | 36 | 3097 | GSK | 1000 | 76 | 65 | 49 | 44 |

| Choudhury 2005 | 12 | 260 | Indep. | 1000 | 52 | 67 | 39 | 54 |

| GSK FLTA3025 2005 | 6 | 640 | GSK | 500, 1000 | 69 | 64 | ‐ | ‐ |

| GSK SCO104925 2008a | 3 | 84 | GSK | 1000 | 77 | 64 | ‐ | ‐ |

| GSK SCO30002 2005 | 12 | 256 | GSK | 1000 | 82 | 65 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hanania 2003a | 6 | 368 | GSK | 500 | 63 | 64 | 57 | 42 |

| Hattotuwa 2002 | 3 | 36 | GSK | 1000 | 87 | 65 | 63 | 46 |

| Kerwin 2013a,b | 6 | 413 | GSK | 100 | 66 | 62 | 46 | 42 |

| Lapperre 2009 | 30 | 55 | GSK | 1000 | 86 | 60 | 43 | 55 |

| Mahler 2002a | 6 | 349 | GSK | 1000 | 66 | 65 | 55 | 41 |

| Martinez 2013a,b | 6 | 612 | GSK | 100, 200 | 72 | 62 | 43 | 48 |

| Paggiaro 1998 | 6 | 281 | ‐ | 1000 | 74 | 63 | ‐ | 57 |

| Schermer 2009 | 36 | 190 | Indep. | 1000 | 71 | 59 | 28 | 64 |

| van Grunsven 2003 | 24 | 48 | GSK | 500 | 52 | 47 | 9 | 97 |

| Verhoeven 2002 | 6 | 23 | GSK | 1000 | 82 | 55 | 26 | 63 |

| WM 22 m | 459 | ‐ | ‐ | 72 | 62 | 43 | 54 | |

| Fluticasone/LABA combination versus LABA monotherapy (n = 15) | ||||||||

| Anzueto 2009 | 12 | 797 | GSK | 500 | 54 | 65 | 57 | 34 |

| Calverley 2003 TRISTANa | 12 | 731 | GSK | 1000 | 73 | 63 | 43 | 45 |

| Calverley 2007 TORCHa | 36 | 3088 | GSK | 1000 | 76 | 65 | 49 | 44 |

| Dal Negro 2003 | 12 | 12 | ‐ | 500 | 92 | ‐ | 42 | 50 |

| Dransfield 2013b | 12 | 3255 | GSK | 50, 100, 200 | 57 | 64 | ‐ | 45 |

| Ferguson 2008 | 12 | 782 | GSK | 500 | 55 | 65 | 56 | 33 |

| GSK FCO30002 2005 | 3 | 140 | GSK | 1000 | 66 | 62 | ‐ | ‐ |

| GSK SCO100470 2006 | 6 | 1050 | GSK | 500 | 78 | 64 | ‐ | ‐ |

| GSK SCO104925 2008a | 3 | 77 | GSK | 1000 | 77 | 64 | ‐ | ‐ |

| GSK SCO40041 2008 | 36 | 186 | GSK | 500 | 61 | 66 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hanania 2003a | 6 | 355 | GSK | 500 | 63 | 64 | 57 | 42 |

| Kardos 2007 | 10 | 994 | GSK | 1000 | 76 | 64 | 37 | 40 |

| Kerwin 2013a,b | 6 | 617 | GSK | 100 | 67 | 63 | 46 | 43 |

| Mahler 2002a | 6 | 325 | GSK | 1000 | 66 | 65 | 55 | 41 |

| Martinez 2013a,b | 6 | 610 | GSK | 100, 200 | 72 | 62 | 43 | 48 |

| WM 16 m | 867 | ‐ | ‐ | 69 | 64 | 53 | 42 | |

aMulti‐arm studies making both comparisons of interest (ICS vs placebo and ICS/LABA vs LABA).

bStudies using vilanterol as the LABA combination and monotherapy comparator, with fluticasone furoate.

Dose is given as the total received per day (i.e. 500 signifies 250 morning and evening).

WM = weighted mean.

2. Budesonide—summary of studies and baseline characteristics.

| Study ID | Duration (m) | N Rand | Funder | ICS dose (mcg) | % Male | Mean age | Pack‐years | % pred FEV1 |

| Budesonide versus placebo (n = 13) | ||||||||

| Bourbeau 1998 | 6 | 79 | AZ | 640 | 79 | 66 | 51 | 37 |

| Calverley 2003ba | 12 | 513 | GSK | 640 | 76 | 64 | 35 | 36 |

| Laptseva 2002 | 6 | 49 | NR | 640 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mirici 2001 | 3 | 50 | NR | 640 | 75 | 53 | 27 | 62 |

| Ozol 2005 | 6 | 26 | NR | 640 | 69 | 65 | 45 | 59 |

| Pauwels 1999 | 36 | 1277 | AZ | 640 | 73 | 52 | 39 | 77 |

| Renkema 1996 | 24 | 39 | AZ | 1280 | 100 | 55 | NR | 64 |

| Senderovitz 1999 | 6 | 26 | NR | 640 | 54 | 61 | NR | NR |

| Shaker 2009 | 36 | 254 | AZ | 640 | 58 | 64 | 56 | 52 |

| Szafranski 2003a | 12 | 403 | AZ | 640 | 79 | 64 | 45 | 36 |

| Tashkin 2008 SHINEa | 6 | 575 | AZ | 640 | 68 | 63 | 41 | 40 |

| Vestbo 1999 | 36 | 290 | AZ | 640 | 88 | 59 | NR | 87 |

| Yildiz 2004 | 3 | 38 | ? | 1280 | 100 | 67 | 51 | 46 |

| WM 23 m | 278 | ‐ | ‐ | 77 | 61 | 43 | 54 | |

| Budesonide/LABA combination versus LABA monotherapy (n = 7) | ||||||||

| Calverley 2003ba | 12 | 509 | GSK | 640 | 76 | 64 | 35 | 36 |

| Calverley 2010 | 11 | 481 | Chiesi | 640 | 81 | 64 | 39 | 42 |

| Fukuchi 2013 | 3 | 1293 | AZ | 640 | 89 | 65 | 44 | 41 |

| Rennard 2009 | 12 | 1483 | AZ | 320, 640 | 63 | 63 | NR | 39 |

| Sharafkhaneh 2012 | 12 | 1219 | AZ | 320, 640 | 62 | 63 | 44 | 38 |

| Szafranski 2003a | 12 | 409 | AZ | 640 | 79 | 64 | 45 | 36 |

| Tashkin 2008 SHINEa | 6 | 1129 | AZ | 320, 640 | 68 | 63 | 41 | 40 |

| WM 9 m | 932 | ‐ | ‐ | 75 | 64 | 41 | 39 | |

aMulti‐arm studies making both comparisons of interest (ICS vs placebo and ICS/LABA vs LABA).

Dose is given as the total received per day (i.e. 640 signifies 320 morning and evening).

WM = weighted mean.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each trial can be found in Characteristics of included studies. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were largely similar across trials, with the exception of which medications participants were allowed to continue taking during the study period. In most studies, participants were required to be over the age of 40 and to have a smoking history of at least 10 pack‐years. In terms of lung function, most studies required values consistent with a GOLD diagnosis of COPD. Studies excluded participants if they had asthma or any other respiratory disorder. Other common exclusion criteria included recent lower respiratory tract infection, the need for long‐term or nocturnal oxygen therapy and recent use of antibiotics or oral corticosteroids (usually within four to six weeks of screening).

Baseline characteristics of participants

Baseline data are given for individual trial arms in Characteristics of included studies tables and are summarised across fluticasone and budesonide studies in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. All of the trials recruited more men than women, with a mean of around 70% and 75% in the fluticasone and budesonide studies, respectively (range 52% to 100%). Mean age within the trials ranged from 47 to 67 years, and the overall mean was similar in the fluticasone and budesonide studies (˜63 years). Smoking history as measured by overall pack‐years (one pack‐year = one pack of 20 cigarettes per day for one year) was reported in three‐quarters of the studies, and the mean was higher in the fluticasone combination therapy studies (53 pack‐years) than in the other sets of trials; all were between 41 and 43 pack‐years overall. The range across all trials was 27 to 63 pack‐years. Percentage predicted FEV1, an indicator of disease severity, was reported in most trials. Overall means for fluticasone and budesonide were very similar (47% and 48%, respectively). One outlier in the fluticasone monotherapy studies recruited a much less severe population (those showing early signs and symptoms of COPD; van Grunsven 2003), with nine mean pack‐years and percentage predicted FEV1 of 97. Two budesonide monotherapy studies also recruited less severe populations, with percentage predicted FEV1 of 77 and 87 (Pauwels 1999; Vestbo 1999). None of these three studies reported the primary outcome.

Characteristics of the interventions

Of the 26 fluticasone studies, 18 compared fluticasone monotherapy versus placebo, and 15 compared fluticasone/LABA combination versus LABA monotherapy (12 using salmeterol and three using the new LABA, vilanterol). Seven trials used multi‐arm double‐dummy designs that performed both comparisons of interest (Calverley 2003 TRISTAN; Calverley 2007 TORCH; GSK SCO104925 2008; Hanania 2003; Mahler 2002), including two newly published trials using vilanterol and fluticasone furoate (Kerwin 2013; Martinez 2013). Fifteen fluticasone studies used fluticasone propionate at a total daily dose of 1000 mcg, and seven used 500 mcg. One further study, GSK FLTA3025 2005, included both doses. The three vilanterol studies used fluticasone furoate at total daily doses of 50, 100 and 200 mcg, and 25 mcg of vilanterol.

Of the 17 budesonide studies, 13 compared budesonide monotherapy versus placebo, and seven compared budesonide/formoterol combination versus formoterol monotherapy. Three studies had four or more arms and performed both comparisons of interest (Calverley 2003b; Szafranski 2003; Tashkin 2008 SHINE). Twelve studies used a total daily budesonide dose of 640 mcg, and two studies used a daily dose of 1280 mcg (Renkema 1996; Yildiz 2004). Three studies used more than one dose (Rennard 2009; Sharafkhaneh 2012), including one that had a total of six arms (Tashkin 2008 SHINE): three combination arms, budesonide 640 mcg, formoterol 18 mcg and placebo. Formoterol as monotherapy control or in combination with budesonide was given at a total daily dose of 18 mcg in all studies.

Table 5 presents the beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) equivalent doses for the included treatments. As shown, higher‐dose budesonide (1280 mcg/d = 1280 BDP) is more similar to the lower dose of fluticasone (500 mcg/d = 1000 BDP). Fluticasone furoate doses of 100 mcg and 200 mcg daily are equivalent to fluticasone propionate 250 mcg twice daily (1000 BDP) and 500 mcg twice daily (2000 BDP) respectively, and the lowest dose of fluticasone furoate is equivalent to 500 BDP. Only the 100 mcg dose of fluticasone furoate is currently licensed for use in COPD

3. BDP equivalent doses.

| Drug | Daily dose (mcg) | BDP equivalent (mcg) |

| Budesonide | 320 | 320 |

| 640 | 640 | |

| 1280 | 1280 | |

| Fluticasone | 500 (propionate) | 1000 |

| 1000 (propionate) | 2000 | |

| 50 (furoate) | 500 | |

| 100 (furoate) | 1000 | |

| 200 (furoate) | 2000 |

In most studies, participants were allowed short‐acting bronchodilators and treatment for acute exacerbations. Most studies also allowed people to continue on some long‐acting treatments that were not the treatments under study (usually theophylline, mucolytics, anticholinergics). Run‐in periods varied somewhat in length and nature. Most ranged from two to eight weeks; some required all bronchodilator treatment, ICS alone or ICS and LABA treatment to be tapered off; others used placebo and oral corticosteroids; and a subset did not describe the procedures used.

Transitivity and similarity

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Inclusion and exclusion criteria, as described above, were considered comparable between the two sets of trials; although variation was noted in the allowed co‐medications between individual trials, this was not systematically different between the fluticasone and budesonide studies.

Baseline characteristics: Although variation between trials was seen, we did not consider that baseline characteristics systematically differed between budesonide monotherapy and fluticasone monotherapy trials, or between budesonide combination therapy and fluticasone combination therapy trials (see above and Table 3; Table 4).

Intervention characteristics: Budesonide and fluticasone studies most often used the respective commonly used twice‐daily dose, although the once‐daily fluticasone furoate studies introduced a potential source of heterogeneity. More important, the fluticasone studies generally used the Diskus or Accuhaler, and the budesonide studies used the Turbuhaler device; this may have confounded the common placebo comparator.

Methodology: We were concerned that funding for the fluticasone and budesonide trials was systematically different, but in light of similar inclusion criteria, baseline characteristics and study designs, we believed that funding alone was not a reason to believe that the transitivity assumption did not hold. However, although the monotherapy trials were of a comparable duration (weighted means of 22 and 23 months), the fluticasone combination therapy trials were a lot longer than the budesonide combination therapy trials (16 and nine months, respectively). Risk of bias was similar across all studies and did not differ systematically between those funded by the two main drug companies. Similarly, although fluticasone monotherapy trials had somewhat larger sample sizes than budesonide monotherapy trials, this finding was not deemed significant. The two sets of combination therapy trials had very similar mean sample sizes.

Control group event rates: Event rates for placebo monotherapy comparisons and for LABA combination therapy comparisons are presented in Table 6. Differences were noted between fluticasone and placebo for both monotherapy and combination therapy comparisons, with fluticasone studies consistently showing higher control group event rates. Inspection of control events showed that Calverley 2007 TORCH, which observed a large population over a longer time scale than most other studies (three years), was skewing the event rates. Although four other long‐term fluticasone monotherapy studies (two to three years) were identified, they had smaller populations, did not contribute to all of the outcomes and did not observe the same magnitude of event rates. With this study removed, control group events were much more similar between the two drugs (presented in brackets). Overall, considered in light of similar baselines and inclusion criteria, it is unlikely that the figures represent true differences in baseline event rates of the two populations.

4. Control group event rates.

| Monotherapy comparison—Placebo control events | Combination comparison—LABA control events | |||

| Fluticasone | Budesonide | Fluticasone | Budesonide | |

| Pneumonia‐related serious adverse events | 2.5%, 77/310 | 0.9%, 4/445 | 2.5%, 134/5420 | 0.9%, 19/2079 |

| 0.5% without TORCH | 0.7% without TORCH | |||

| All‐cause mortality | 7.6%, 282/3713 | 2.1%, 37/1763 | 5.1%, 254/5489 | 1.5%, 37/2534 |

| 2.4% without TORCH | 1.2% without TORCH | |||

| All‐cause serious adverse events | 25%, 882/3471 | 15%, 268/1763 | 21%, 1152/5489 | 14%, 356/2534 |

| 14% without TORCH | 14% without TORCH | |||

For the fluticasone control groups with and without the large 3‐year TORCH study.

In light of all of the information collected, we decided to calculate the indirect comparison of fluticasone and budesonide monotherapy via placebo because the only potential confound was the inhaler device used, and all other moderating factors were considered comparable. For the reasons outlined regarding control group event rates, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding Calverley 2007 TORCH.

For the combination therapy comparison, we considered the common LABA comparison to systematically differ between the two sets of combination studies; fluticasone studies used either salmeterol or vilanterol, which differed in their delivery and dosing schedules, and budesonide was always compared with formoterol. In addition, the fluticasone studies were much longer, and the same funding and device issues existed as for the monotherapy studies. As such, we did not perform an indirect comparison to compare fluticasone/LABA versus budesonide/LABA.

Outcomes and analysis structure

Unless otherwise stated, all of the analyses were conducted as proposed with fixed‐effect models using Mantel‐Haenszel methods. Several outcomes included some zero cells, but estimates were barely affected in sensitivity analyses using the Peto method. Therefore, Peto odds ratios were used only for 'mortality due to pneumonia', because events for this outcome were very rare. The quality of evidence for each outcome was rated using GRADEPro software, and this information is presented in Table 1 (fluticasone) and Table 2 (budesonide).

Indirect comparisons performed to compare fluticasone with budesonide monotherapy are presented for the primary outcome and for three secondary outcomes (all‐cause mortality, all non‐fatal serious adverse events and all pneumonia events). Although we did not foresee the inclusion of fluticasone furoate when we conceived of the protocol, we decided to combine these data with the fluticasone propionate data on the basis of consistency observed in the monotherapy subgroup of each of the relevant direct analyses (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.4).

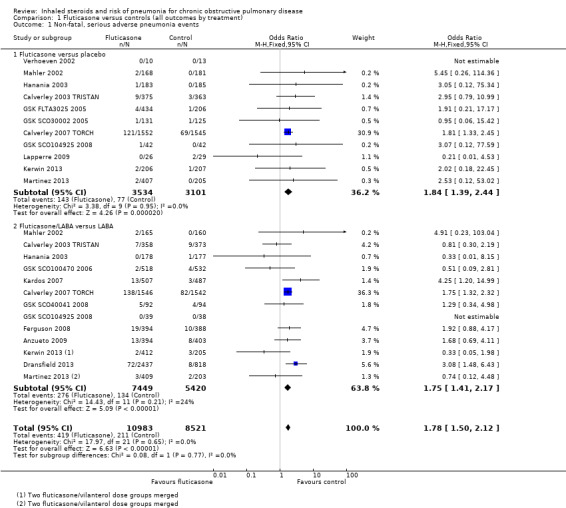

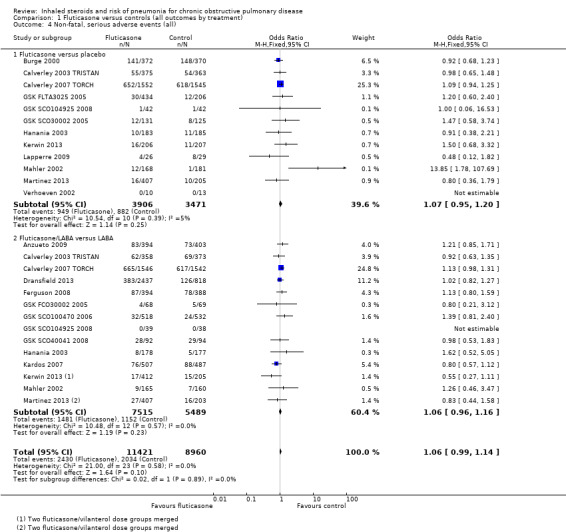

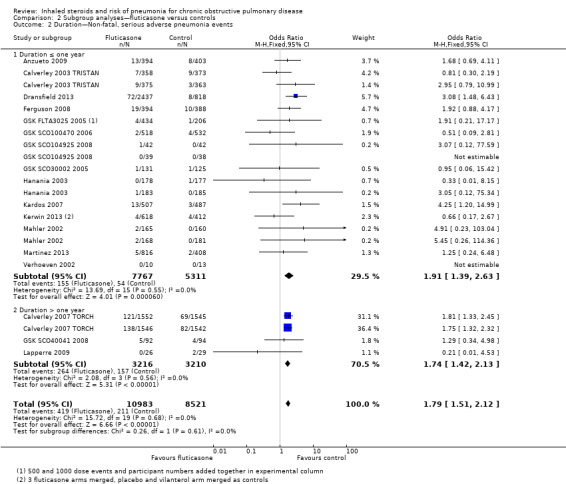

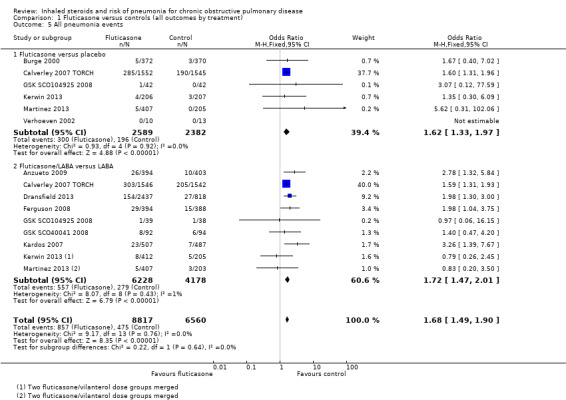

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fluticasone versus controls (all outcomes by treatment), Outcome 1 Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

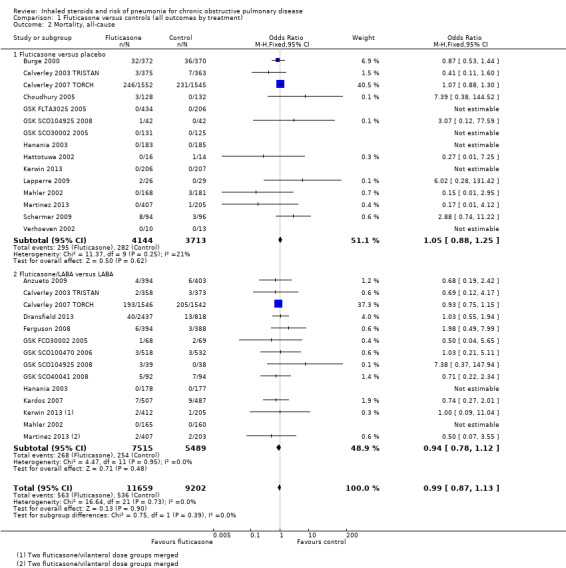

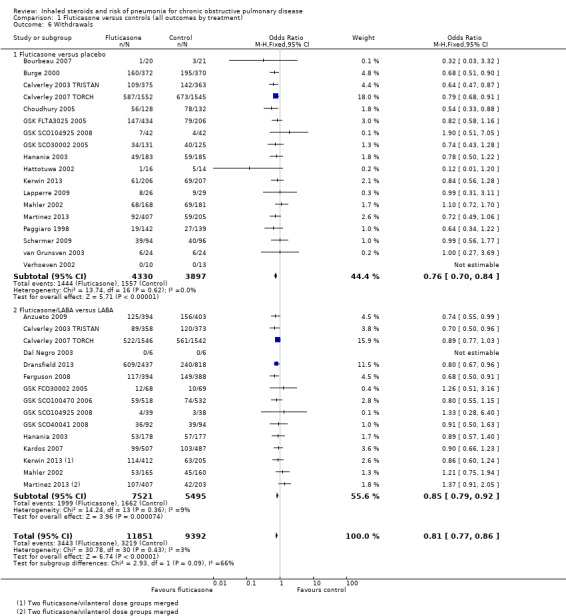

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fluticasone versus controls (all outcomes by treatment), Outcome 2 Mortality, all‐cause.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fluticasone versus controls (all outcomes by treatment), Outcome 4 Non‐fatal, serious adverse events (all).

For the primary outcome, 'non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events', data were organised into three sets of subgroups to explore the effects of three prespecified potential moderators. Subgroup analyses for daily dose, duration of ICS therapy (≤ one year and > one year) and baseline severity (< 50% FEV1 predicted and ≥ 50% FEV1 predicted) are presented separately for fluticasone and budesonide in comparisons three and four, respectively.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis while removing studies judged to be at high risk of bias because of high or uneven levels of dropout. Of the 17 studies that fell into this category, eight reported the primary outcome and were removed from the analysis (fluticasone: Calverley 2003 TRISTAN; Ferguson 2008; GSK SCO40041 2008; Lapperre 2009; Mahler 2002; budesonide: Rennard 2009; Shaker 2009; Sharafkhaneh 2012).

Excluded studies

Thirty‐one references were excluded after full texts were consulted. Reasons for exclusion were 'wrong comparison' (n = 19), discontinuation of study (n = 6), 'asthma diagnosis' (n = 2) and 'treatment period less than 12 weeks (n = 2). One study is awaiting classification (only abstract is available), and recruitment for one study was ongoing in March 2014. Full details are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies.

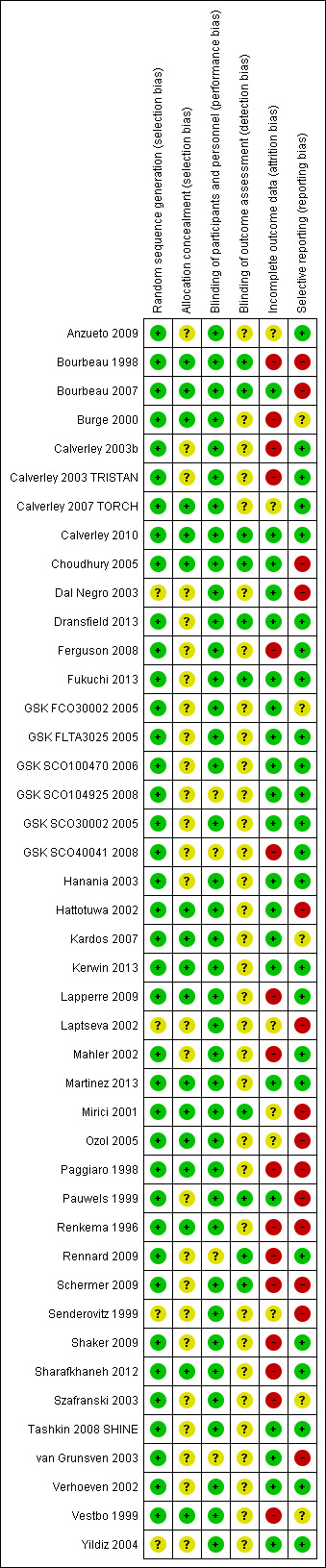

Risk of bias in included studies

Studies generally were well conducted and were rated as low or unclear risk of bias for all four of the allocation and blinding parameters. However, in almost half of the studies, potential for bias was due to attrition and selective outcome reporting. Full details of our judgements for each study, as well as supporting information for each judgement, can be found in Characteristics of included studies. A summary of risk of bias across all studies is shown in Figure 3.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Studies were rated for potential biases introduced by the method of sequence generation (e.g. computerised random number generator) and by the methods used to conceal the allocation sequence from those recruiting people into the studies.

Most studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for sequence generation (n = 39). Although not all of these studies adequately described sequence generation methods, all were funded by pharmaceutical companies that had previously confirmed their methods. The remaining four studies were rated 'unclear' because they did not describe their methods in detail and did not appear to be funded by a pharmaceutical company (Dal Negro 2003; Senderovitz 1999; Yildiz 2004).

Allocation concealment was not well reported, and only 17 studies were given a rating of low risk of bias because they adequately described the methods used. However, no studies were considered to be at high risk of bias, and the remaining 26 studies were given an 'unclear' rating.

Blinding

The risk of bias introduced by methods of blinding was rated separately for blinding of participants and personnel and for blinding of the people assessing outcomes.

Most studies stated that double‐blind procedures were used, and trial reports or registrations usually confirmed that this approach included both participants and investigators. For this reason, most studies were rated as low risk of bias (n = 39), and the remaining four were rated as 'unclear'. No studies were open‐label or used inadequate blinding procedures, so none were judged to be at high risk of bias.

Quite often, it was difficult to ascertain from the study reports who the outcome assessors were and for which outcomes the blinding applied. Only 10 studies gave enough information to allow a judgement of low risk of bias to be made, and the remaining 33 were rated as 'unclear'.

Incomplete outcome data

Around half of the studies were rated as low risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data (n = 21), either because the number of dropouts per group was low and even, or because the quantity and distribution of missing data were deemed acceptable given the method of imputation (e.g. intention‐to‐treat analysis using last observation carried forward). Sixteen studies were rated as high risk of bias, usually because dropout was very high in both groups, or because dropout was much higher in one group than in another. In the remaining six studies, authors considered that the information regarding attrition was not sufficient to permit judgement of whether dropout and methods of data imputation were likely to have affected the results.

Selective reporting

More than half of the studies were rated as low risk of bias for selective outcome reporting (n = 24), either because reported outcomes could be checked against the outcomes stated in a prospectively registered protocol, or because study authors provided additional data through personal communication. Five studies were rated as unclear, usually because no clear evidence on missing outcomes was available, but no trial registration could be found to confirm that all prespecified outcomes were properly reported. In all cases, attempts were made to contact trial authors for clarification; this is detailed in each study's risk of bias table in Characteristics of included studies. The remaining 14 studies were judged to be at high risk of bias, either because outcomes stated in the trial registration were missing or poorly reported in the published report, or because several key outcomes analysed in this review were not reported.

Other potential sources of bias

No additional sources of bias were identified.

Effects of interventions

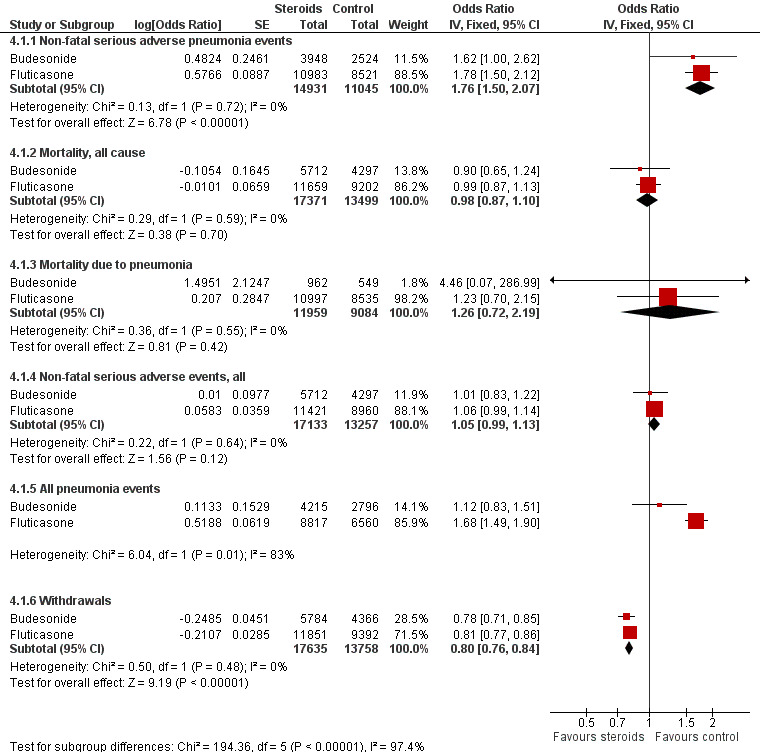

In comparisons one and three, studies are pooled for fluticasone and budesonide, respectively, and are subgrouped in each case in terms of whether each randomly assigned group also received a long‐acting beta‐agonist. Comparisons two and four show additional subgroup analyses for the primary outcome of non‐fatal serious adverse events for fluticasone and budesonide, respectively.

Comparison five presents results for the indirect comparison of fluticasone and budesonide via the common placebo comparator (Figure 1). Comparison six refers to the equivalent comparison of fluticasone with budesonide given as combination therapy with a long‐acting beta‐agonist. As described above, no indirect comparison was undertaken for combination therapy because of violations of transitivity and similarity.

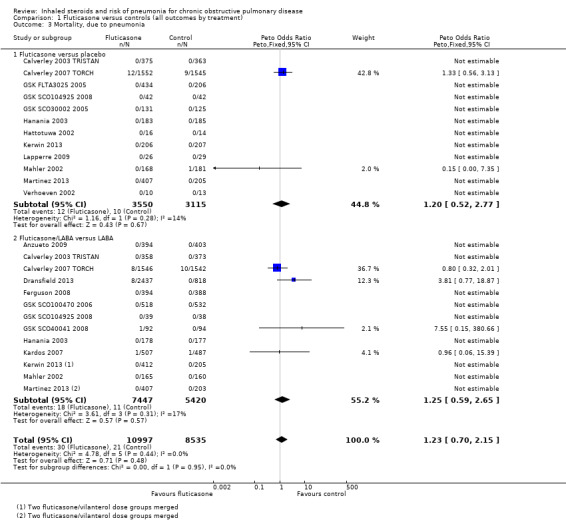

For illustration and visual comparison of the two drugs, effects of all fluticasone studies (comparison one) and all budesonide studies (comparison three) are presented together for each outcome in Figure 4. No statistical heterogeneity was noted between the pooled effect for budesonide and that of fluticasone for all outcomes except 'all pneumonia events'; for this reason the effects are not pooled for this outcome.

4.

Summary of pooled effects of trials comparing ICS versus placebo and combination versus LABA. Non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events were those requiring hospital admission. Data for all pneumonia events were not pooled because of heterogeneity.

Comparison one: fluticasone versus controls (all outcomes subgrouped to compare ICS vs placebo with ICS/LABA vs LABA)

1.1 Primary outcome: non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events (requiring hospital admission)

Twenty‐four comparisons in 17 studies were analysed (n = 19,504), with seven studies contributing data to both the 'fluticasone versus placebo' and 'fluticasone/LABA versus LABA' subgroups. Fluticasone increased the incidence of non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.50 to 2.12; I2 = 0%, P value 0.65), with no significant heterogeneity noted between studies. No significant evidence indicated that the odds of having a serious adverse pneumonia event were differentially affected by fluticasone alone (against placebo) compared with fluticasone/LABA combination (against LABA alone) (I2 = 0%, P value 0.77). The outcome was rated of high quality.

1.2 Mortality, all‐cause

Twenty‐nine comparisons in 22 fluticasone studies were included in the analysis (n = 20,861), although seven comparisons did not contribute to the pooled estimate because no events were reported in either group. No evidence suggested a difference between fluticasone and controls (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.13; I2 = 0%, P value 0.73), and a test for subgroup differences between 'fluticasone versus placebo' and 'fluticasone/LABA versus LABA' comparisons was not significant (I2 = 0%, P value 0.39). Evidence was rated of high quality.

1.3 Mortality, due to pneumonia

Data for pneumonia‐related deaths were available for 25 comparisons in 18 studies (n = 19,532). However, all but five comparisons observed no events, and Calverley 2007 TORCH accounted for 80% of the analysis weight across its two comparisons. No difference was detected between fluticasone and control overall (Peto OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.15; I2 = 0%, P value 0.95), and no observable subgroup differences were reported between the monotherapy and combination therapy subgroups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.44). Evidence was rated of moderate quality, being downgraded once for imprecision because so few events were reported.

1.4. Non‐fatal serious adverse events, all‐cause

Nineteen studies across 26 comparisons reported all‐cause serious adverse events (n = 20,381). The odds of a serious adverse event were higher with fluticasone than with control (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.16; I2 = 0%, P value 0.66). The lower confidence just crossed the line of no effect, but no significant heterogeneity was noted between studies. No evidence suggested a difference between monotherapy and combination therapy subgroups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.58). Evidence was rated of high quality.

1.5. All pneumonia events

Fifteen studies making 11 comparisons reported the outcome (n = 15,377), and Calverley 2007 TORCH carried almost 80% of the weight across the analysis. The odds of any pneumonia event were significantly greater with fluticasone than with control (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.49 to 1.90), with no important heterogeneity observed between studies (I2 = 0%, P value 0.76) or subgroups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.64). The outcome was underreported across the studies, so evidence was downgraded for publication bias, and was rated of moderate quality.

1.6. Withdrawals

Data from 26 studies (33 comparisons, n = 21,243) show that withdrawals were much less common on fluticasone than on control, with no significant heterogeneity noted (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.86; I2 = 3%, P value 0.43). The effect was larger for fluticasone monotherapy, but the difference between subgroups was not statistically significant (I2 = 66%, P value 0.09). No reasons suggested the need to downgrade the evidence from high quality.

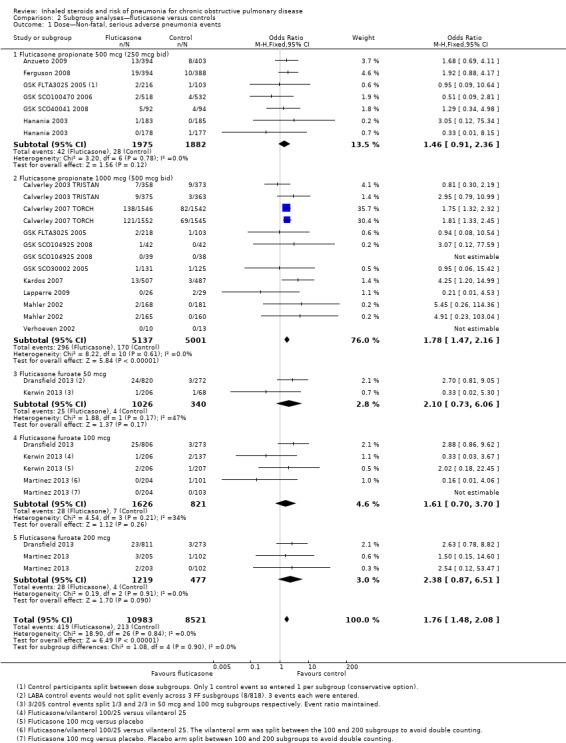

Comparison two: subgroup analyses—fluticasone versus controls

Dose: Combining all studies and organising by fluticasone dose did not reveal significant subgroup differences between doses (I2 = 0%, P value 0.90; Analysis 2.1). Pooled effects for the three furoate dose subgroups (50 mcg, 100 mcg and 200 mcg once a day) contained fewer data and therefore had much wider confidence intervals than the more widely used propionate preparation doses. Higher‐dose fluticasone propionate was the most widely studied and hence has the most precise estimate, but the pooled effect was not statistically different from the other dose subgroups.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analyses—fluticasone versus controls, Outcome 1 Dose—Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

Trial duration: No evidence shows significant differences between the trials with duration of one year or less and the three trials (four comparisons) that followed participants for three years (I2 = 0%, P value 0.61; Analysis 2.2). No significant heterogeneity between individual studies was noted within either subgroup (I2 = 0% in both cases).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analyses—fluticasone versus controls, Outcome 2 Duration—Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

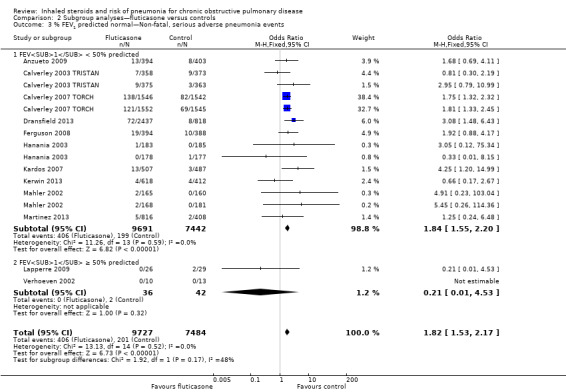

Baseline percentage predicted FEV1 : Studies with a mean baseline percentage predicted FEV1 of less than 50% accounted for 99% of the analysis weight (Analysis 2.3), so no conclusions could be drawn regarding the moderating effect of baseline severity.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analyses—fluticasone versus controls, Outcome 3 % FEV1 predicted normal—Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

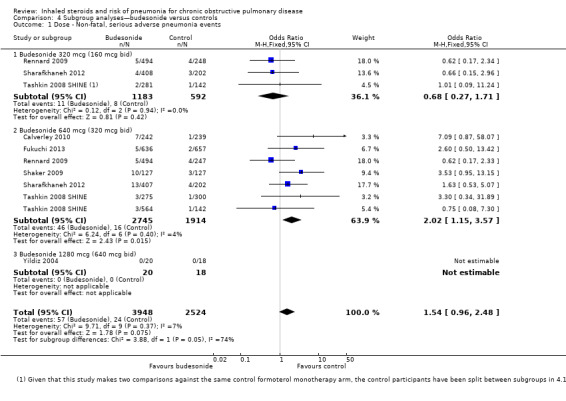

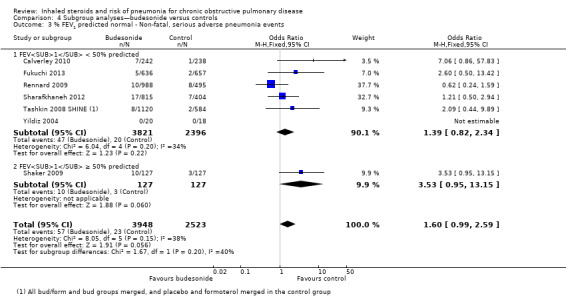

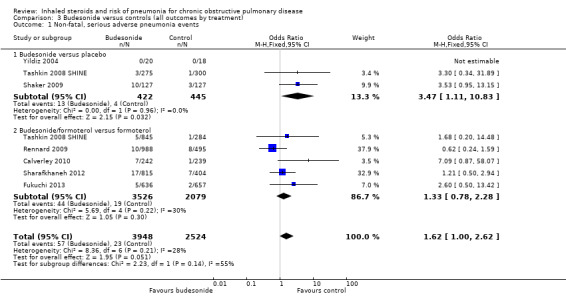

Comparison three: budesonide versus controls (all outcomes subgrouped to compare ICS vs placebo with ICS/LABA vs LABA)

3.1 Primary outcome: non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events (requiring hospital admission)

Data for eight comparisons in seven studies were analysed (n = 6472), with Tashkin 2008 SHINE contributing data to both 'budesonide versus placebo' and 'budesonide/LABA versus LABA' subgroups. Budesonide increased non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.62), and, although a degree of variation was noted between study results, it was not significant (I2 = 28%, P value 0.21). Heterogeneity was evident between the monotherapy and combination subgroups, but the test for differences was not statistically significant (I2 = 55%, P value 0.14). The confidence intervals around the pooled estimate were quite wide but were not considered serious enough to warrant downgrading. However, because two‐thirds of the budesonide studies did not appear in the analysis, the outcome was downgraded once for publication bias and was rated of moderate quality.

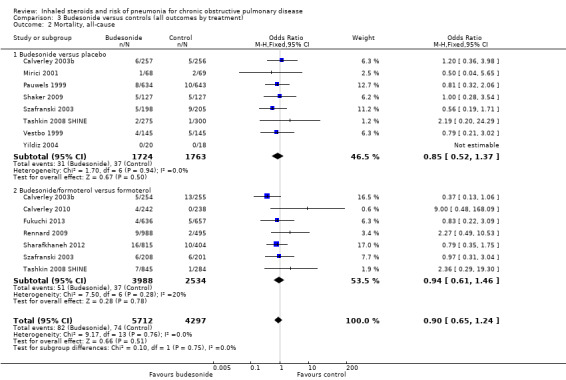

3.2. Mortality, all‐cause

Budesonide did not significantly affect all‐cause mortality relative to control interventions (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.24), based on 15 comparisons in 12 studies (n = 10,009). Heterogeneity was not significant across studies (I2 = 0%, P value 0.76), and no statistically significant difference was noted between the monotherapy and combination therapy subgroups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.75). Evidence was rated of moderate quality after being downgraded once for imprecision because the confidence intervals included significant benefit and harm.

3.3. Mortality, due to pneumonia

Only three budesonide studies reported the outcome (n = 1511), of which two studies observed no events in either group. No conclusions could be made from Sharafkhaneh 2012, which observed one event in the budesonide/LABA group. Evidence was rated of very low quality, being downgraded twice for imprecision and once for publication bias.

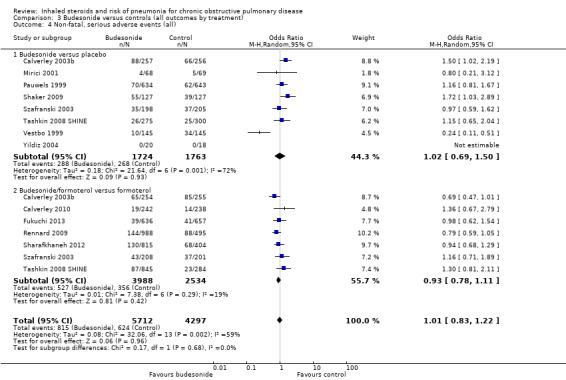

3.4. Non‐fatal serious adverse events, all‐cause

Fifteen comparisons in 12 studies were analysed (n = 10,009). Budesonide was not found to increase the odds of a serious adverse event (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.22), although significant heterogeneity was noted between studies (I2 = 59%, P value 0.002), so a random‐effects analysis was used and the outcome was downgraded for inconsistency to moderate quality. No heterogeneity was observed between the subgroups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.68).

An outlier in the budesonide versus placebo subgroup was removed in a post hoc sensitivity analysis (Vestbo 1999), which changed the effect for the subgroup to favour the control (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.55) with no within‐subgroup heterogeneity (previously I2 = 72%). The study recruited a less severe population, which might explain the difference in effect.

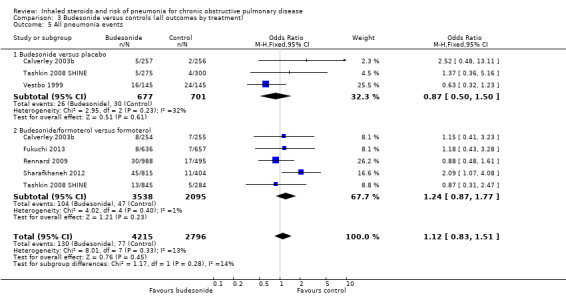

3.5. All pneumonia events

Not enough evidence was obtained to rule out a significant increase or a potential reduction in pneumonia events on budesonide compared with controls (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.51; eight comparisons in six studies; n = 7011). A degree of unexplained heterogeneity was observed between studies (I2 = 13%, P value 0.33) and between treatment subgroups (I2 = 14%, P value 0.28), neither of which was significant. Although confidence intervals were quite wide, findings were not deemed serious enough to warrant downgrading of the evidence. However, because most of the budesonide studies did not appear in the analysis, the outcome was downgraded for publication bias and was rated of moderate quality.

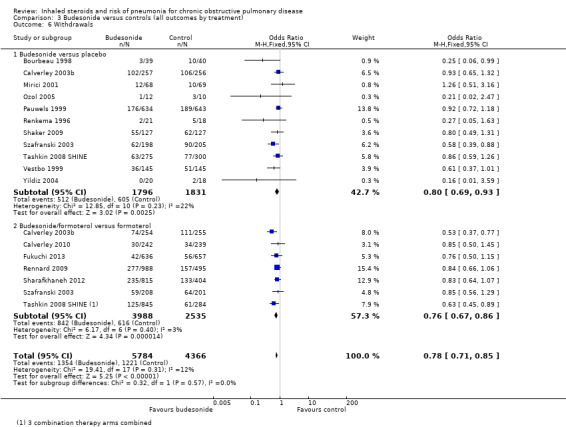

3.6. Withdrawals

When 18 comparisons in 15 studies were combined (n = 10,150), withdrawals were seen to be less common in the budesonide groups than in the control groups (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.85). No important heterogeneity was noted between individual studies (I2 = 12%, P value 0.31) or between monotherapy and combination therapy subgroups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.57). Evidence was rated of high quality.

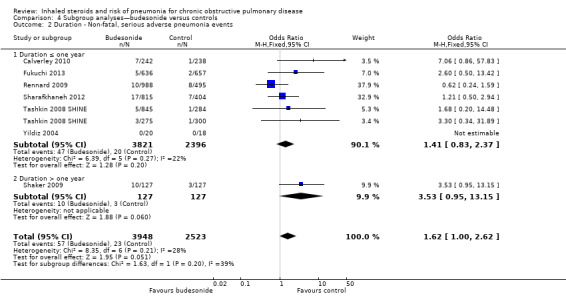

Comparison four: subgroup analyses—budesonide versus controls

Dose: When all budesonide studies were subgrouped according to daily dose, the difference between 320 mcg and 640 mcg was significant (I2 = 74%, P value 0.05; Analysis 4.1); the higher dose increased non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.57), and no significant difference was observed for the lower dose (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.71). The only study using the highest dose of 1280 mcg, Yildiz 2004, did not contribute data to the analysis because no events occurred in either group.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analyses—budesonide versus controls, Outcome 1 Dose ‐ Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

Trial duration: The difference between five studies lasting a year or less and Shaker 2009 (which followed participants for a minimum of two years) was not significant (I2 = 39%, P value 0.20; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analyses—budesonide versus controls, Outcome 2 Duration ‐ Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

Baseline percentage predicted FEV1: When studies were subgrouped according to baseline severity, differences were not significant (I2 = 40%, P value 0.20; Analysis 4.3), and only one study reported a baseline mean FEV1 above 50% predicted (Shaker 2009).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analyses—budesonide versus controls, Outcome 3 % FEV1 predicted normal ‐ Non‐fatal, serious adverse pneumonia events.

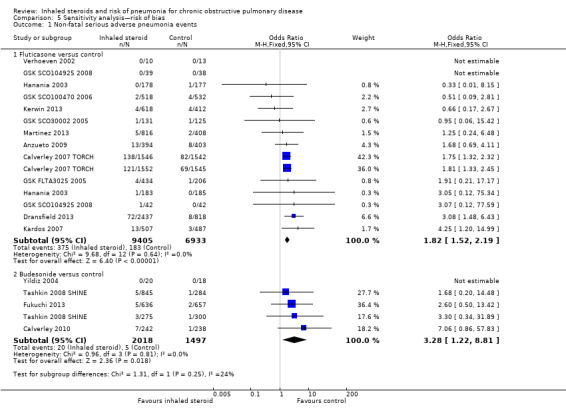

Comparison five: sensitivity analysis—risk of bias

5.1 Non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events

5.1.1 Fluticasone versus controls

Four fluticasone studies representing six comparisons rated at high risk for attrition were removed from the primary outcome in a sensitivity analysis. The estimate gave a slightly larger effect of fluticasone on pneumonia than the main analysis (15 RCTs; n = 16,338; OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.52 to 2.19).

5.1.2 Budesonide versus controls

Three studies judged to be at high risk of bias due to high or uneven levels of attrition were removed from the primary outcome in a sensitivity analysis. The effect from the remaining four studies was larger but more imprecise because far fewer events were included in the analysis (5 RCTs; n = 3515; OR 3.28, 95% CI 1.22 to 8.81).

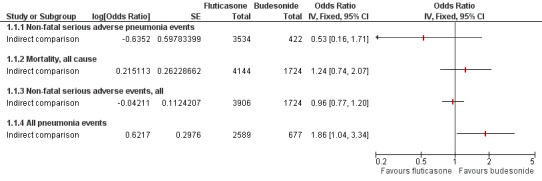

Comparison six: indirect comparison of fluticasone and budesonide monotherapy

We calculated the relative effects of fluticasone and budesonide for four outcomes by comparing their effects against placebo (see Figure 1). No studies directly comparing the two drugs met this review's inclusion criteria, but cohort data are summarised in Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews.

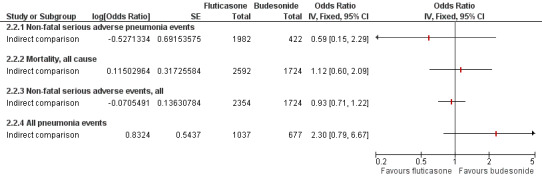

All four outcomes were downgraded for indirectness because no direct evidence was found and the estimate was obtained purely from indirect comparisons. None of the outcomes were downgraded for risk of bias or inconsistency. The indirect comparisons are presented in Figure 5 and are summarised below, and the sensitivity analysis removing Calverley 2007 TORCH is shown in Figure 6.

5.

Indirect comparisons of fluticasone and budesonide monotherapy.

Non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events were defined as those requiring hospital admission.

6.

Indirect comparisons of fluticasone and budesonide monotherapy—Sensitivity analysis removing (Calverley 2007 TORCH).

6.1 Non‐fatal serious adverse pneumonia events

The point estimate favoured fluticasone, but the difference was not significant and the confidence intervals were very wide (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.71). In addition to being downgraded for indirectness, the outcome was downgraded twice for imprecision and was rated as very low quality.

6.2 Mortality, all‐cause

The point estimate favoured budesonide, but the difference was not significant and the confidence intervals were wide (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.07). Evidence was also downgraded once for imprecision and was rated of low quality.

6.3 All non‐fatal serious adverse events

The difference between fluticasone and budesonide was not significant, and the confidence intervals were much tighter than for the other two indirect comparisons (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.20). The evidence was not downgraded for any other reason and was rated of moderate quality.

6.4 All pneumonia events

A significant difference was noted between fluticasone and budesonide, although the confidence interval was quite wide (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.34). The evidence was not downgraded for any other reason and was rated of moderate quality. When Calverley 2007 TORCH was removed from the sensitivity analysis, the difference was larger in magnitude but was much less precise and was not statistically significant (OR 2.30, 95% CI 0.79 to 6.67).

Comparison seven: indirect comparison of fluticasone/LABA and budesonide/LABA combination therapy

For the reasons described in 'Transitivity and similarity', we chose not to calculate an indirect comparison for combination therapy. Recent studies directly comparing fluticasone/salmeterol with budesonide/formoterol were not comparable with the design or time scales used in the rest of this review (Blais 2010; Janson 2013 [PATHOS]; Partridge 2009; Roberts 2011), but their findings are discussed in Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found a total of 43 studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review, with more evidence for fluticasone (26 studies, n = 21,247) than budesonide (17 studies, n = 10,150). Evidence from the budesonide studies was more inconsistent and less precise, and the mean duration of trials was shorter.